In the world of mechanics, precision in language is as crucial as precision with a wrench. Every seasoned professional understands that diagnosing an issue, explaining a problem, or guiding a repair hinges on crystal-clear communication. Yet, one word often thrown around with casual abandon, despite its immense power and specificity, is ‘worst.’ It’s a term that encapsulates the ultimate degree of ‘bad,’ ‘ill,’ or ‘deficient,’ yet its true meaning and nuanced applications are frequently misunderstood.

Misinterpreting ‘worst’ can lead to everything from misdiagnoses in a complex system to ineffective troubleshooting, or even unnecessary worry for vehicle owners. Just as you wouldn’t misidentify a spark plug as a camshaft, you shouldn’t misuse a word as definitive as ‘worst.’ It’s time to bust some of the most pervasive myths surrounding this superlative, giving you the linguistic tools to articulate problems and solutions with the accuracy a true mechanic demands. Let’s delve into what ‘worst’ truly means, what it implies, and why understanding its intricacies is key to navigating the mechanical world.

1. **Myth #1: ‘Worst’ is Always an Objective, Universal Truth.**There’s a common misconception that when something is described as ‘the worst,’ there’s an undisputed, universal agreement on its status. We often hear someone declare a car model, a repair technique, or even a specific part as ‘the worst,’ expecting everyone to nod in agreement. However, dictionary definitions clearly state that ‘As with bad, worst is often a person’s opinion.’ This highlights a fundamental truth: ‘worst’ is frequently subjective, colored by individual perspectives and criteria.

What someone considers ‘the worst’ in a mechanical context—be it the worst fuel efficiency, the worst handling, or the worst part reliability—depends entirely on the metrics they are applying. The context explicitly notes, ‘What someone thinks of as the worst something depends on what they’re judging that thing on.’ For a racing enthusiast, the ‘worst’ might be a slow lap time; for a commuter, it could be frequent breakdowns or high maintenance costs. Understanding this subjectivity is vital in diagnostics and recommendations.

Mechanics know that one person’s ‘worst’ might be another’s acceptable compromise. When discussing an issue, recognizing that the customer’s definition of ‘worst’ might differ from a technical assessment can bridge communication gaps. It helps in explaining *why* a certain component or performance characteristic is suboptimal *for their specific needs*, rather than simply stating it as an absolute, universally bad feature.

2. **Myth #2: ‘Worst’ Only Refers to Inferior Quality or Performance.**Many people confine their understanding of ‘worst’ purely to tangible failures or measurable deficiencies, such as a component with the ‘worst quality’ materials or an engine exhibiting the ‘worst performance.’ While these are certainly valid applications, the scope of ‘worst’ extends far beyond mere physical inferiority. The context provides a broader spectrum of meaning, noting ‘worst’ can describe something as ‘most faulty or unsatisfactory.’

However, it also extends to being ‘most unpleasant, unattractive, or disagreeable.’ This expanded definition is crucial in areas like automotive design and user experience. A car’s interior might not be ‘faulty,’ but if its ergonomics are ‘most unpleasant’ or its aesthetic ‘most unattractive,’ it could legitimately be described as having ‘the worst interior design’ by a user. These are not failures of function but failures of appeal or comfort.

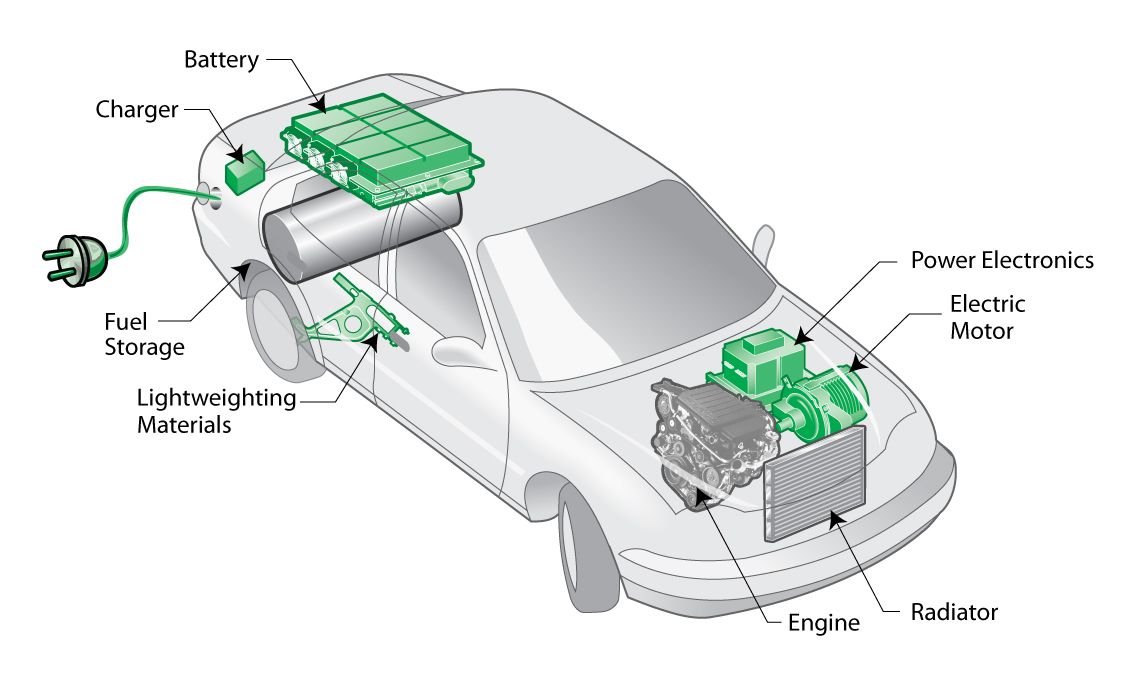

Similarly, a mechanic might encounter a vehicle that, while technically functional, is ‘most disagreeable’ to work on due to poor accessibility or proprietary components. So, while the engine runs, the *experience* of servicing it can be ‘the worst.’ Recognizing this broader emotional and experiential dimension of ‘worst’ allows for a more holistic understanding of a mechanical system’s overall value and user satisfaction.

3. **Myth #3: Any ‘Bad’ Situation is Automatically ‘Worst.’**In everyday conversation, the terms ‘bad’ and ‘worst’ are often conflated, with people describing nearly any negative situation as ‘the worst.’ This linguistic imprecision, however, obscures the true meaning and power of the superlative ‘worst.’ The context makes it abundantly clear: ‘worst is a superlative of the word bad. Simply put, worst describes something as being the baddest out of a group, category, list, and the like.’ It denotes the absolute extreme, not just any negative condition.

To say a component is ‘bad’ indicates it’s not good, perhaps faulty or underperforming. To say it’s ‘worse’ implies a comparison, indicating a greater degree of badness than something else. But to say it’s ‘the worst’ elevates it to the pinnacle of deficiency within its category. This isn’t merely a semantic distinction; it’s a critical difference for diagnostic and decision-making processes in mechanics. Identifying something as ‘bad’ suggests it needs attention, while identifying it as ‘the worst’ points to the most critical failure or the lowest possible standard.

Understanding this hierarchy helps mechanics prioritize problems. Not every ‘bad’ sound or ‘bad’ reading warrants the same immediate alarm as something that is truly ‘the worst’ among its peers or conditions. Distinguishing between merely ‘bad’ and definitively ‘worst’ allows for a more accurate assessment of urgency, severity, and the potential impact on a system’s overall integrity or safety.

4. **Myth #4: ‘Worst’ Can Be Interchanged with ‘Badly’ as an Adverb.**Precision in language extends to understanding grammatical roles, especially when diagnosing and explaining mechanical phenomena. A common linguistic slip is to use ‘worst’ when ‘badly’ (or its superlative ‘worst’ as an adverb) would be more appropriate, or to confuse the adverbial ‘worst’ with the adjectival ‘worst.’ The context provides clarity: ‘As an adverb, worst is the superlative of the word badly and describes something as being done in as bad a manner as possible.’ This highlights its function describing how an action is performed.

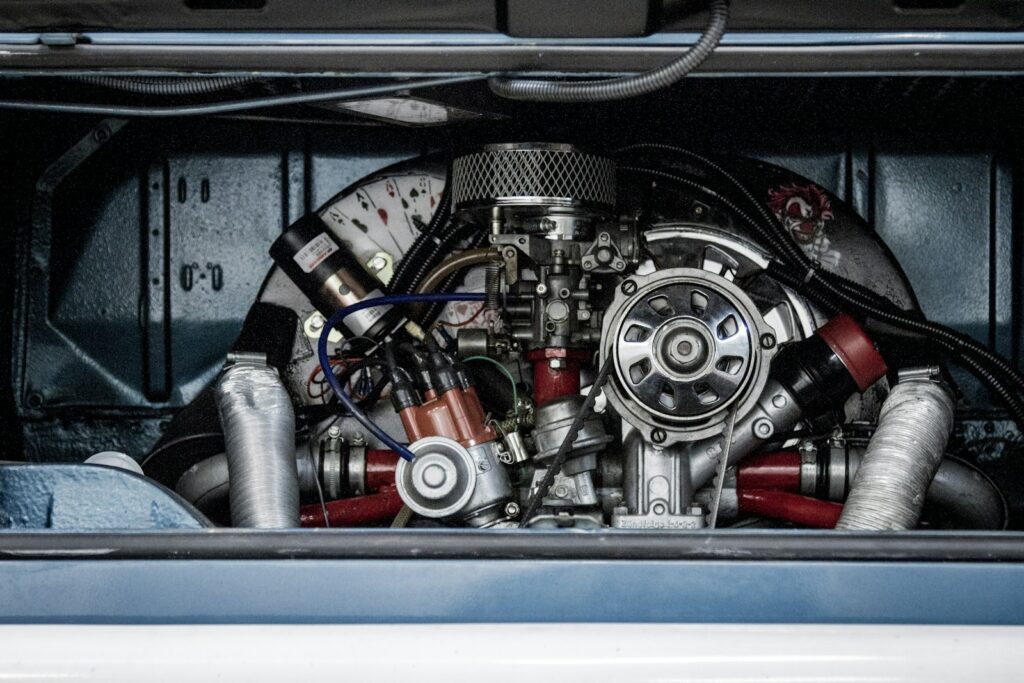

Consider the difference: stating ‘This engine is the worst’ uses ‘worst’ as an adjective, describing the engine’s inherent quality. However, saying ‘This engine runs worst when it’s cold’ uses ‘worst’ as an adverb, describing *how* the engine performs under specific conditions – in the *worst manner possible* for running. The context also lists ‘badly’ as an adverb meaning ‘in a bad way; incorrectly, inadequately, or unfavorably,’ with ‘worst’ as its superlative.

This distinction is not just academic; it has practical implications in diagnostics. An engine might not be ‘the worst’ overall (adjective), but it might indeed perform ‘worst’ (adverb) under certain environmental stressors or load conditions. Understanding whether you’re describing the item itself or the way it functions allows for more accurate problem identification and communication, helping to pinpoint if the issue lies with the component’s inherent design or its operational context.

5. **Myth #5: ‘Worst’ is Strictly About Physical Objects or Conditions.**While ‘worst’ is frequently applied to tangible things like a ‘worst engine’ or ‘worst road conditions,’ restricting its meaning to only physical entities overlooks a significant aspect of its usage. The dictionary entries clearly show ‘worst’ extending beyond the material realm. It can describe characteristics of individuals or abstract concepts, such as ‘the worst student in a class’ or ‘the worst person you know.’ It is also used to refer to ‘the worst personality I’ve ever known.’

In a mechanical context, this broader application means that ‘worst’ isn’t confined to faulty components or poor operating conditions. It can also describe abstract elements like procedures, designs, or even intellectual shortcomings. For instance, a technician might refer to ‘the worst repair procedure’ for a specific fault, or an engineer might identify ‘the worst design flaw’ in a system. These are not physical objects, but rather concepts or methods that are deemed most unsatisfactory.

This expanded understanding is crucial for holistic problem-solving. It allows mechanics to evaluate not just the physical state of a machine, but also the efficacy of the processes surrounding it. Identifying ‘the worst method’ for diagnosing an intermittent electrical fault, for example, is just as important as identifying ‘the worst wire’ in the circuit, contributing to more efficient and reliable maintenance practices.

6. **Myth #6: The Forms ‘Badder,’ ‘Baddest,’ or ‘Worser’ are Standard.**In an age of informal communication, nonstandard grammatical forms can easily slip into technical discussions, leading to ambiguity and a lack of professionalism. While phrases like ‘badder’ for ‘worse’ or ‘baddest’ for ‘worst’ might appear in casual speech, it’s imperative for those in technical fields to adhere to standard English. The context explicitly states, ‘The comparative badder (for worse) and superlative baddest (for worst) derived from the positive bad are nonstandard.’ It further clarifies that ‘Worst may be further inflected to form the two additional superlatives worstest (nonstandard) and worstestest (informal, humorous). The comparative worser is also nonstandard.’

These nonstandard forms, while perhaps conveying a point in informal settings, can introduce confusion and undermine credibility in a professional context. When a mechanic describes a component as ‘baddest,’ it lacks the precise, authoritative tone expected in technical diagnostics. Using the correct superlative forms—’worse’ and ‘worst’—ensures clarity and maintains the integrity of technical communication, which is paramount in preventing errors and ensuring correct understanding between professionals and clients.

Adhering to standard English, particularly with such fundamental superlatives, removes any potential for misunderstanding. In a field where safety and performance are critical, eliminating linguistic ambiguities is a non-negotiable aspect of effective communication. Using ‘worst’ correctly is not just about grammatical correctness; it’s about conveying definitive, unambiguous information that can directly impact repairs and operational integrity.

Navigating the intricate landscape of mechanical diagnosis and problem-solving requires more than just technical expertise; it demands a finely tuned understanding of language. Having demystified some of the core misconceptions surrounding the word ‘worst,’ it’s time to delve deeper into its more subtle and often overlooked applications. These next myths will further equip you with the linguistic precision needed to articulate complex issues and make informed decisions, transforming your approach to mechanical challenges. From assessing human factors to preparing for unforeseen calamities, a nuanced grasp of ‘worst’ is an invaluable tool in any mechanic’s arsenal. Let’s uncover these deeper layers of meaning.

7. **Myth #7: ‘Worst’ Exclusively Describes Absolute Malfunction, Not Lacking Skill.**Many in the mechanical world, or even car owners, tend to associate ‘worst’ purely with a catastrophic breakdown or a component that has failed utterly. If an engine isn’t running at all, or a part is physically broken, then it’s deemed ‘the worst.’ This narrow view overlooks an important dimension: ‘worst’ can also describe a profound lack of skill or efficiency, which, while not a direct mechanical failure, can lead to equally problematic outcomes.

According to the dictionary, ‘worst’ can indeed refer to being ‘least efficient or skilled.’ It offers examples like ‘The worst drivers in the country come from that state’ or ‘most lacking in skill; least skilled: the worst typist in the group.’ This means a system or an operator isn’t necessarily broken, but their performance or inherent capability is at the absolute lowest end of the spectrum. In a technical context, this could describe a poorly designed user interface that makes maintenance ‘worst’ for a technician, or a vehicle system that is ‘least efficient’ in its energy use compared to others, even if it functions.

For mechanics, this distinction is vital. It shifts the diagnostic focus from merely identifying physical damage to also evaluating operational efficiency and user interaction. If a vehicle exhibits ‘worst’ fuel economy, the issue might not be a faulty injector, but perhaps a suboptimal engine tune or even a driver’s habits. Understanding that ‘worst’ can apply to skill and efficiency rather than just outright breakage allows for a more comprehensive approach to problem-solving, encompassing human factors and system optimization alongside component repair.

8. **Myth #8: ‘Worst’ Only Refers to Current, Tangible Problems.**It’s natural to think of ‘worst’ as something concrete that is happening right now—the worst noise, the worst leak, the worst wear on a tire. This perspective limits the utility of ‘worst’ to reactive problem-solving, addressing issues only once they have manifested. However, the word ‘worst’ is also profoundly embedded in the language of anticipation and preparedness, pointing towards potential and hypothetical scenarios rather than just present realities.

The context provides several idioms that underscore this forward-looking aspect: ‘Prepare for the worst’ and ‘if worst comes to worst, if the very worst happens.’ These phrases use ‘worst’ as a noun, referring to the most extreme, negative *possible* outcome or condition. It’s about envisioning the ultimate challenge or failure that *could* occur, allowing for proactive planning rather than simply reacting to an existing problem. This isn’t just everyday idiom; it reflects a deep understanding of risk.

In the demanding world of mechanics, preparing for ‘the worst’ is a non-negotiable part of the job. When advising a client on a questionable component, a mechanic considers ‘if worst comes to worst’ to explain potential future failures and associated costs. This involves assessing hypothetical catastrophic failures, planning for emergency repairs, or recommending preventative maintenance to avert the most severe scenarios. Recognizing this dimension of ‘worst’ transforms it from a descriptive term of current problems into a crucial tool for risk assessment, preventative action, and strategic decision-making in vehicle maintenance and repair.

9. **Myth #9: ‘Worst’ Cannot Function as a Verb in a Technical Context.**For many, ‘worst’ exists primarily as an adjective or an adverb, describing states or manners of being. The idea of using ‘worst’ as an action word might seem archaic or entirely foreign to modern technical language. This perception often leads to overlooking a subtle yet powerful application of the word, one that can metaphorically describe overcoming challenges in problem-solving.

The dictionary explicitly defines ‘worst’ as a transitive verb, meaning ‘to defeat; beat.’ It gives an example: ‘He worsted him easily.’ While less common in casual conversation today, this verb form denotes triumphing over an adversary or a challenge. It’s about gaining an advantage, successfully overcoming a difficulty, or emerging victorious in a contest. This isn’t about destruction, but about decisive victory.

Applied to a mechanical context, while you wouldn’t typically say an engine ‘worsted’ a fault, the concept remains relevant in a broader sense. A brilliant diagnostic technique might ‘worst’ a perplexing intermittent electrical issue, meaning it decisively beat or overcame the problem. An innovative engineering solution could be said to ‘worst’ a previous design flaw, effectively defeating the limitations of the old system. Understanding ‘worst’ as a verb enriches our vocabulary for describing successful problem resolution, moving beyond simply ‘fixing’ or ‘repairing’ to conveying the triumph of effective diagnosis and inventive solutions over stubborn mechanical challenges.

10. **Myth #10: The Etymology of ‘Worst’ is Irrelevant to Its Modern Meaning.**Some might argue that delving into the historical origins of a word like ‘worst’ is merely an academic exercise, holding little practical value for a mechanic focused on tangible repairs. This myth suggests that what matters is the contemporary definition, not its linguistic lineage. However, understanding the etymological roots of ‘worst’ reveals how deeply ingrained its meaning of ultimate deficiency truly is, reinforcing its authoritative use in technical contexts.

The context traces ‘worst’ back to its origins: ‘bef. 900; Middle English worste… Old English wur(re)sta… inherited from Germanic… from Proto-Germanic *wirsistaz, superlative form of *ubilaz (“bad, evil”).’ This shows that from its earliest documented use, ‘worst’ has carried the weight of signifying something ‘most evil’ or ‘most bad’ in the most extreme degree. It wasn’t just a casual intensifier but a term rooted in fundamental judgments of quality and condition.

This historical context is not just linguistic trivia; it strengthens the authoritative power of ‘worst’ in professional communication. When a mechanic declares a brake pad system to be ‘the worst,’ they are drawing upon a linguistic legacy that instantly conveys extreme unsuitability, severe faultiness, or the poorest possible condition, directly linked to its origin as the superlative of ‘bad’ and ‘ill.’ This deep historical resonance ensures that the word ‘worst’ is perceived with the gravity it deserves in diagnostics, emphasizing the critical nature of the problem and the urgency of its resolution.

11. **Myth #11: ‘Worst’ Is Incapable of Expressing Extreme Desire or Urgency.**Given its primary association with negativity, failure, and extreme deficiency, it’s a common misconception that ‘worst’ can only be used in a derogatory or critical sense. Many believe its application is strictly limited to describing poor quality, bad performance, or dire situations. This overlooks a fascinating idiomatic usage that flips its emotional polarity, allowing ‘worst’ to convey a profound sense of desire or extreme urgency, particularly in informal communication.

The context highlights this nuanced usage with the idiom: ‘in the worst way, very much; extremely: He needs praise in the worst way.’ Here, ‘in the worst way’ doesn’t mean something is bad or faulty; rather, it intensifies the *degree* of a need or desire to its absolute maximum. It signals an overwhelming craving or an acute requirement. It’s an example of how language can playfully subvert literal meaning to achieve expressive emphasis, taking the concept of ‘the greatest degree’ and applying it to something positive or neutral.

While technical communication demands precision and typically adheres to the literal, negative connotations of ‘worst,’ recognizing this idiomatic usage is crucial for effective client interaction. A customer might exclaim, “I need my car fixed in the worst way!” They aren’t implying that the repair process itself is terrible, but rather that their need for the repair is exceptionally urgent and profound. Understanding this informal intensification allows mechanics to accurately gauge a client’s urgency and emotional state, fostering better communication and a more empathetic approach to service. Being aware of these linguistic subtleties ensures that mechanics can not only speak with authority but also listen with understanding, bridging the gap between technical jargon and everyday expression.

Mastering the nuances of a single word like ‘worst’ might seem like a small detail in the vast field of mechanics, but its implications are far-reaching. From making precise diagnoses to communicating effectively with clients and anticipating future problems, a deep understanding of this superlative enhances every aspect of a mechanic’s work. It’s about equipping yourself with the linguistic tools to describe, analyze, and solve problems with unmatched clarity and authority. So, the next time you encounter something truly ‘worst,’ you’ll have the vocabulary and insight to articulate exactly why, and what needs to be done about it. Because in the world of wrenches and engines, precision in language is, without a doubt, a superpower.