The 1930s stand as a pivotal and often misunderstood decade in American history, characterized by profound economic hardship and significant demographic shifts. Among the most iconic images of this era is the westward migration, a mass movement of people from the drought-stricken Southern Plains towards the promise of California. This journey, frequently and reductively attributed solely to the ‘Dust Bowl,’ was in reality a far more complex phenomenon, driven by a confluence of environmental, economic, and social pressures that reshaped the lives of millions and left an indelible mark on the nation’s consciousness. For many, the road west was not merely a change of address, but a desperate quest for survival, a testament to human resilience in the face of overwhelming adversity.

While popular narratives often condense this intricate exodus into a single, dust-choked image, a deeper examination reveals a tapestry woven from diverse experiences, unexpected destinations, and a broader historical context. It was an era when the American landscape itself seemed to conspire against its inhabitants in certain regions, forcing families to abandon everything they knew in pursuit of a dream often far more elusive than they had imagined. This in-depth exploration seeks to move ‘Beyond the Dust Bowl’ to offer an unfiltered look at the multi-faceted migration of the 1930s, chronicling the journeys of those who left failed farms and struggling communities, carrying their meager possessions and their profound hopes toward California.

Our journey into this transformative period will uncover the true catalysts behind this monumental movement, quantify its impressive scale, and share the human stories etched into the fabric of U.S. Highway 66. We will challenge long-held stereotypes, reveal the often-harsh realities awaiting migrants in California, and set the stage for understanding how this unique chapter in American history became a enduring symbol of both suffering and perseverance.

1. **The True Catalysts of Exodus: Drought, Economics, and the Southern Plains**

The popular perception of the 1930s migration often singularly points to the dramatic dust storms that ravaged parts of the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles. However, the forces compelling families to abandon their homes and head west were far more pervasive and systemic than this singular environmental disaster suggests. It was a complex interplay of natural calamity and economic collapse that created an unbearable environment for many in the Southern Plains, setting the stage for one of the largest internal migrations in American history.

Central to the crisis was a period of severe and widespread drought that gripped the Midwest throughout the mid-1930s. This prolonged absence of rainfall devastated agricultural lands, making farming unsustainable and rendering vast tracts of land barren. James N. Gregory, a history professor at the University of Washington and author of “American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California,” emphasizes that “The Dust Bowl that forced many families on the road wasn’t just caused by winds lifting the topsoil. Severe drought was widespread in the mid-1930s.”

Compounding the environmental catastrophe was a profound economic downturn that had already left many rural communities teetering on the brink. Beyond the failing crops and parched earth, “Farm communities in the larger region were also hurt by falling cotton prices.” For an agricultural economy heavily reliant on this cash crop, plummeting prices meant an already precarious existence became utterly untenable, stripping families of their livelihoods and any hope for recovery.

Gregory succinctly summarizes the confluence of these devastating factors: “All of this contributed to what has become known as the Dust Bowl migration.” It was a perfect storm of environmental degradation and economic despair, pushing families to make the agonizing decision to leave generations of history behind in search of any opportunity that might offer a chance at a better life, however distant or uncertain.

2. **The Scale of the Journey: Numbers and Origins of the “Dust Bowl” Migrants**

The sheer volume of people displaced by the hardships of the 1930s was staggering, creating a demographic shift that captured national attention and ignited fierce debates in destination states. While pinpointing an exact number of these migrants remains a subject of historical discussion, the estimates underscore the immense scale of this human movement, revealing a nation in flux.

Christy Gavin and Garth Milam, writing in California State University, Bakersfield’s Dust Bowl Migration Archives, provide a significant figure: “by some estimates, as many as 400,000 migrants headed west to California during the 1930s.” This torrent of humanity fundamentally altered the social and economic landscape of the Golden State, placing immense pressure on its resources and communities, and leaving a lasting imprint on its culture.

Contrary to the popular image of a migration solely from the ‘Dust Bowl’ states, the migrants originated from a broader geographical area. “More than half a million left the region in the 1930s, mostly heading for California,” a region encompassing “four southern plains states: Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri.” This clarifies that the term ‘Dust Bowl refugee’ was, in many cases, a misnomer, as many came from areas not directly devastated by the infamous dust storms, but still suffering from the same underlying economic and environmental crises.

This mass exodus was particularly noteworthy because it occurred “in a decade when migration rates dropped nationwide.” The fact that families were leaving the southern plains in such significant numbers, despite a general decline in national mobility, highlights the extreme conditions they faced. Their plight drew considerable attention, making them a visible symbol of the Great Depression’s profound impact on the American populace.

3. **A Highway of Hope and Hardship: The Migrant’s Journey West**

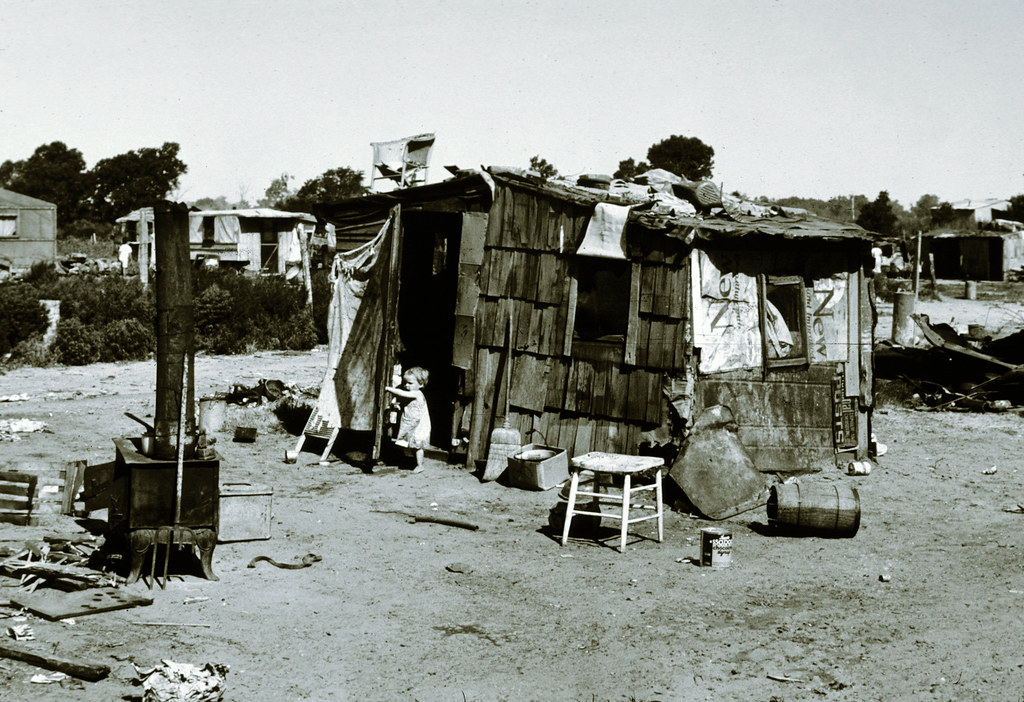

The physical journey from the ravaged Southern Plains to the perceived promise of California was itself a harrowing ordeal, defined by immense discomfort, uncertainty, and a poignant display of human determination. Families, stripped of most of their possessions by economic ruin, packed what little they had into vehicles that were often barely roadworthy, embarking on a quest for survival.

Migrants “squeezed into trucks and jalopies—beat-up old cars—laden with their meager possessions and headed west.” These vehicles became temporary homes, carrying not just people but the remnants of their former lives, symbolizing both the desperation of their flight and the fragile hope they clung to for the future. Each mile traversed was a step further from destitution and a step closer to the unknown.

The chosen artery for this epic migration was often the iconic U.S. Highway 66. This legendary route, stretching from Chicago to Los Angeles, became a ribbon of hope for “many taking the old U.S. Highway 66.” It was more than just a road; it was a symbol of the westward pull, an escape route from the dust and despair, and a tangible link to the dreams of a better life in California.

Yet, the journey was far from easy. The image of vehicles “laden with their meager possessions” paints a picture of intense privation. Every spare inch was utilized, every item carefully chosen for its utility or sentimental value. This stark reality of their travel underscored the profound economic hardship they were fleeing, transforming the simple act of transportation into an act of profound and collective struggle.

4. **Life on the Road: Personal Narratives of Survival and Seeking Work**

Behind the statistics and the broad historical narratives lie countless individual stories, each a testament to the extraordinary courage and endurance of the migrants. These personal accounts offer a vivid, human-centered perspective on the daily struggles and aspirations that defined the journey west, bringing to life the immense challenges faced by families on the move.

One such poignant narrative comes from Byrd Monford Morgan, a former migrant who shared his experiences in a 1981 oral history interview. His recollection provides a window into the practicalities and the communal spirit of the journey. “Dad bought a truck to bring what we could,” he recalled, highlighting the sheer necessity and improvisation involved in securing transport for an entire family unit.

Morgan’s account further illustrates the incredible packing feats and the number of people crammed into these vehicles: “There were fifteen people to ride out in this truck, in addition to what we could haul.” This speaks volumes about the scarcity of resources and the collective nature of their migration, where multiple family members and even extended relatives would share the same meager transport.

The cargo itself offers a snapshot of their priorities and the life they hoped to rebuild: “including the family’s kitchen table, sewing machines, sacks to use in picking cotton, and five-gallon cans packed with cookies baked by Morgan’s stepmother.” These items were not luxuries but tools for future labor and comforting reminders of home, all meticulously preserved through the arduous journey. The mention of cotton sacks foreshadows their immediate goal upon arrival: to find agricultural work.

Survival on the road also necessitated resourcefulness and resilience. Morgan recalled that “Along the way, the family camped out by the side of the highway.” These makeshift encampments were a common sight, transforming roadsides into temporary communities of migrants, sharing their experiences, fears, and hopes under the open sky. It was a journey marked by constant movement, always seeking the next opportunity.

Upon reaching California, the quest for work began immediately. As Morgan recounted, “When the family got to California, they stopped at farms and asked if they needed workers, and picked everything from tomatoes to grapes.” This desperate search for employment, often involving grueling labor for meager wages, was the immediate reality awaiting most migrants, a stark contrast to the golden dreams that had fueled their westward trek.

Read more about: Beyond the Buzz: 14 Surprising Signs You’re More Stressed Than You Realize (And How to Bounce Back)

5. **Beyond the “Dust Bowl” Label: Diverse Origins and the Broader Southern Diaspora**

The term “Dust Bowl refugees,” while evocative and deeply embedded in popular culture, presents a somewhat misleading picture of the 1930s migration. It suggests a singular origin from the areas most severely impacted by dust storms, yet the reality was far more expansive and nuanced. Understanding the true geographical spread of these migrants is crucial to appreciating the full scope of this historical event.

As the context makes clear, “The press called them Dust Bowl refugees, although few came from the area devastated by dust storms.” This journalistic shorthand, while powerful in its imagery, inadvertently narrowed the perceived origins of a much broader movement. The designation, though widely used, did not fully capture the diverse backgrounds of those who sought a new life in California.

Instead, these families hailed “from a broad area encompassing four southern plains states: Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri.” This extensive footprint indicates that economic hardship, agricultural decline, and the widespread drought—rather than just the dramatic dust clouds—were the dominant forces driving the exodus across a significant portion of the South. “More than half a million left the region in the 1930s, mostly heading for California,” a figure that underscores the regional nature of the crisis.

Moreover, this particular westward movement of predominantly White families from Oklahoma and neighboring states was not an isolated incident. It was, in fact, “part of a broader exodus from the South that included the Great Migration of southern Black families and still larger outmigration of southern White families.” This places the “Dust Bowl migration” within the context of the larger historical phenomenon known as the Southern Diaspora, which saw “nearly 20 million people leave the economically troubled South in the first seven and half decades of the 20th century.”

This crucial contextualization highlights that while the 1930s migration to California had its unique characteristics and became a focal point of national attention, it was also a continuation and intensification of a “migration sequence from that region that had been going on for decades and would continue long after the 1930s.” It was a deeply rooted historical trend, amplified by the unprecedented crises of the Great Depression and the severe environmental challenges of the era.

6. **The California Dream Deferred: Initial Experiences and the “Okie Crisis”**

For many migrants, the promise of California, the “fields of plenty” described in song and story, quickly gave way to a harsh reality upon arrival. The Golden State, while offering stark visual contrast to the dust-choked plains they had left behind, was not the immediate haven of opportunity many had envisioned. Instead, they encountered new forms of hardship, prejudice, and a society grappling with its own internal struggles.

The influx of such a large and impoverished population sparked significant social and political tension within California. By 1939, “the public was in the midst of a massive debate over the ‘Okie crisis,'” a term that reflected the widespread apprehension and often hostile sentiment towards the new arrivals. This debate was fueled by concerns over strained resources, increased competition for scarce jobs, and cultural differences.

Journalists and photographers played a significant role in shaping public perception, often focusing on “scenes of desperation along the highways and in farm labor camps.” These powerful, sometimes sensationalized, images reinforced the stereotype of the “Dustbowl refugee” and contributed to the sense of crisis. While intending to highlight suffering, these portrayals also inadvertently fueled prejudice against the migrants, who were often labeled ‘Okies’ or ‘Arkies’ regardless of their specific state of origin.

These perceptions, often rooted in misinformation, solidified an image of the migrants as a homogeneous group of destitute farm folk, a picture that, as we shall see, was not entirely accurate. The term “Dustbowl refugee” itself, though widely used, was often “mistakenly assuming that people had fled the dramatic dust storms that had ravaged counties in the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles earlier in the decade,” when in fact their origins were far more diverse.

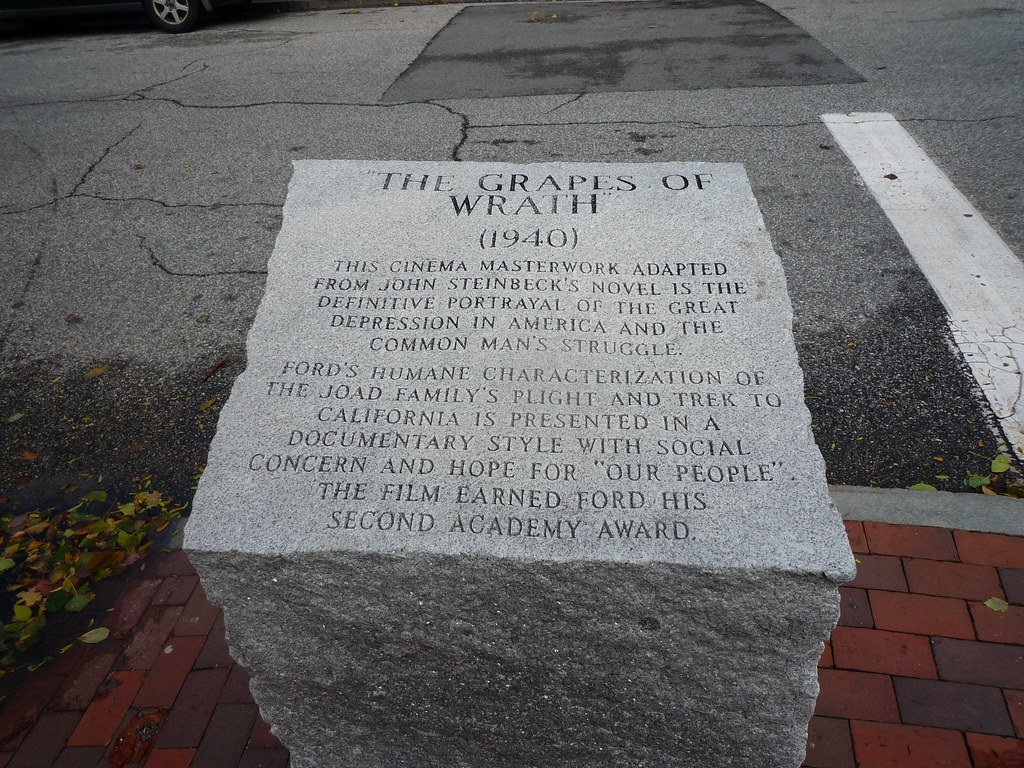

This difficult reception and the ensuing “Okie crisis” provided the backdrop against which John Steinbeck would weave his unforgettable narrative. His novel, “The Grapes of Wrath,” became instrumental in “crystaliz[ing] the image of ‘Okies and Arkies’ struggling to survive in California’s Central Valley.” While bringing their plight to national attention, it also cemented a particular, often tragic, understanding of their initial experiences in the Promised Land, highlighting the profound gap between the California dream and the deferred realities faced by many.”

, “_words_section1”: “1948

The 1930s migration to California was far more than a simple demographic shift; it was a crucible that forged new cultural identities, reshaped the socio-economic fabric of an entire state, and left an indelible mark on the American consciousness. Having explored the arduous journey and initial struggles, we now turn our gaze to the profound and lasting impact of this monumental movement. This section will peel back the layers of history to reveal how these ‘Okies’ and ‘Arkies,’ often arriving with little more than hope, profoundly influenced California’s culture, transformed its labor landscape, and became an enduring symbol of American resilience in the face of abject poverty.

7. **The Grapes of Wrath: A National Conscience Awakened**

John Steinbeck’s seminal novel, “The Grapes of Wrath,” published in the spring of 1939, emerged not merely as a literary triumph but as a profound societal earthquake. It took the scattered, often sensationalized, stories of migrant suffering and distilled them into a singular, powerful narrative that resonated deeply across the nation. Steinbeck accomplished what countless journalists and photographers, despite their best efforts, could not: he ensured that the plight of the ‘Okies’ would be etched permanently into the American memory, transforming them into one of the Great Depression’s most potent symbols.

Before Steinbeck’s masterpiece, the public discourse in California was already consumed by the “Okie crisis,” a debate fueled by rising tensions and widespread apprehension towards the influx of impoverished newcomers. Newspaper headlines, frequently depicting “scenes of desperation along the highways and in farm labor camps,” had certainly drawn attention to the issue. Yet, these accounts, while impactful, often reinforced stereotypes and sometimes failed to convey the full human dignity and despair of the migrants.

Steinbeck’s genius lay in his ability to humanize the statistics, to give voice and soul to the faceless masses. His story of the dispossessed Joad family, driven from their Oklahoma farm and struggling to survive amidst the perceived plenty of California’s Central Valley, touched the conscience of a nation already grappling with its own economic wounds. It was a narrative that compelled empathy, challenged indifference, and exposed the stark injustices faced by those pursuing a fundamental American dream that seemed increasingly out of reach.

The novel “crystaliz[ed] the image of ‘Okies and Arkies’ struggling to survive in California’s Central Valley,” cementing a vivid, albeit often tragic, understanding of their initial experiences. By doing so, “The Grapes of Wrath” not only recorded history but actively made it, shaping public perception and sparking a national conversation about poverty, labor, and social responsibility that continues to echo through generations. It became an uncomfortable mirror reflecting the nation’s failures and the extraordinary resilience of its people.

8. **Socio-Economic Transformations: Migrants in California’s Labor Landscape**

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of migrants profoundly reshaped California’s labor landscape, particularly in its agricultural heartland. Before the Depression, the workforce picking the state’s abundant crops—from the “two dozen different kinds of fruits and vegetables” to “the highest quality cotton fiber”—was primarily composed of “Mexicans, Filipinos, and single white males.” However, the 1930s saw a dramatic shift as “more and more whites looking for harvest labor jobs, many of them traveling as families,” entered this demanding sector.

This influx of new laborers, often desperate for any work, intensified competition for already scarce jobs and depressed wages. Many families, like the Morgans, upon reaching California, would “stop at farms and ask if they needed workers, and picked everything from tomatoes to grapes,” demonstrating the immediate, grueling reality of their new existence. They were vital to California’s agricultural economy, yet often exploited and relegated to the lowest rungs of the economic ladder.

It is a pervasive stereotype that all these migrants were impoverished farm folk destined solely for California’s fields. However, this image, while prominent in popular culture, does not tell the full story. As historical data from the 1940 Census reveals, which tracked 286,746 people from the southern plains who moved to California between 1935 and 1940, the migration was more diverse in its destinations than often assumed.

Crucially, this data “disrupts one stereotype.” While indeed “some of the migrants were farm folk who sought work in the Central Valley,” a significant portion “left towns and cities and headed for Los Angeles and other urban areas.” This highlights that the migrants were not a monolithic group but included those with urban skills and aspirations, contributing to a broader transformation of California’s burgeoning cities as well as its agricultural valleys. Their impact permeated various sectors, fostering new communities and economies.

9. **The Emergence of an “Okie Subculture” and its Lasting Influence**

Beyond their economic trials, the migrants from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, and Missouri brought with them a rich cultural heritage that profoundly influenced California’s society. This cultural transfer led to the development of a distinct “Okie subculture,” which, as James N. Gregory highlights in “American Exodus,” has since “grown into an essential element in California’s cultural landscape.” These newcomers, despite facing prejudice, were not merely recipients of Californian culture but active contributors who shaped it in unexpected ways.

One of the most significant cultural contributions was their strong allegiance to evangelical Protestantism. As Gregory “vividly depicts,” Southwesterners carried their faith westward, establishing new churches and infusing the state with a vibrant religious tradition. This religious fervor provided a bedrock of community and solace amidst hardship, becoming a cornerstone of their identity in a new and often unwelcoming land. It fostered social networks and mutual aid, vital for survival and adaptation.

Accompanying their religious convictions were deeply ingrained “plain-folk American” values. These included a strong work ethic, self-reliance, community solidarity, and a profound sense of patriotism. These values, forged in the crucible of rural hardship and migration, were not easily shed. Instead, they became distinguishing characteristics of the ‘Okie’ communities, influencing local customs, social interactions, and even political leanings within their new Californian homes.

Perhaps one of the most beloved and enduring legacies of this migration is the profound impact on California’s musical landscape: a love of country music. The migrants brought their fiddles, guitars, and gospel harmonies, seeding a flourishing country music scene that would later become synonymous with Bakersfield. This unique sound, often called the ‘Bakersfield Sound,’ was a direct descendant of the melodies carried across U.S. Highway 66, proving that even in destitution, culture finds a way to thrive and enrich.

This rich cultural infusion, from religious practices to musical genres and core values, demonstrates that the migrants were not passive recipients of aid but active agents in shaping the state. Their determination to maintain their traditions while adapting to new circumstances laid the groundwork for a dynamic and complex Californian identity, proving that resilience is not just about survival, but also about the enduring power of heritage.

10. **Updating the Narrative: Beyond Steinbeck’s Prophecy**

While “The Grapes of Wrath” powerfully captured the initial struggles of the migrants, it also presented a vision of their future that proved, in many ways, to be incomplete. John Steinbeck himself, while deeply empathetic, was “not at all sure that California could or would provide an adequate home,” and his novel “foresaw a difficult future for the Okies and Arkies.” He believed a great deal depended “upon important changes in the structure of California agriculture,” implying that without such changes, their plight would remain dire.

However, the historical trajectory of the Dust Bowl migrants in the decades following 1939 defied many of these initial understandings and expectations. James N. Gregory notes that “the experiences of the Dust Bowl migrants in subsequent decades defied many of the understandings and expectations that governed his 1939 portrait.” This divergence between literary foresight and historical reality offers a fascinating insight into the adaptability and long-term success of these resilient families.

Steinbeck never chronicled the post-1930s evolution of the ‘Okies,’ a fact Gregory suggests is “too bad, for he would have been quite surprised.” Many of the migrants, who were initially perceived as transient farm laborers, eventually settled, found stable employment, and integrated into California society. Their narratives shifted from immediate survival to building new lives, establishing communities, and raising families within the Golden State, contributing significantly to its growth and diversity.

This updated perspective acknowledges that while the initial struggles were undeniably severe, the story of the Dust Bowl migration did not end in perpetual despair. It evolved into a complex narrative of integration, upward mobility, and the enduring impact of a people who, against formidable odds, made California their home. Their journey, therefore, stands as a testament not only to hardship but also to remarkable perseverance and the capacity for societal change and individual advancement.

11. **The Enduring Legacy: Poverty Stories, Race Stories, and the American Identity**

The Dust Bowl migration of the 1930s holds a singular and complex position in how Americans understand the history of poverty and public policy. As James Gregory notes, for almost seven decades, this saga has been kept alive by “journalists and filmmakers, college teachers and museum curators, songwriters and novelists, and of course historians.” It has transcended a mere historical event to become a powerful cultural touchstone, a narrative constantly revisited and reinterpreted.

Despite being “but one episode out of many struggles with poverty during the 1930s,” the Dust Bowl migration achieved a unique status, becoming “something of synecdoche, the single most common image that later generations would use to memorialize the hardships of that decade.” This immense symbolic weight underscores its enduring resonance, serving as a concentrated embodiment of the broader suffering and resilience experienced across America during the Great Depression. It’s a lens through which an entire era is often viewed.

The ongoing fascination with the Dust Bowl narrative is also intricately tied to the evolving dynamics of “race and poverty” in America. Gregory keenly observes that this migration stands as “one of the last great stories depicting white Americans as victims of severe poverty and social prejudice.” In a national discourse often dominated by narratives of racialized poverty, the ‘Okie’ story provides a crucial, if sometimes uncomfortable, counterpoint, prompting deeper reflections on the multifaceted nature of hardship in American history.

This story of white families from Oklahoma and neighboring states journeying to California, therefore, serves many purposes. It is a narrative “that many Americans have needed to tell, for many different reasons,” reflecting different generational understandings of economic struggle, social mobility, and the complex interplay of identity and adversity. The Dust Bowl migration remains a powerful, multifaceted symbol, continually informing our understanding of American identity and the ongoing dialogue surrounding poverty.

Read more about: From Getaway Cars to Tragic Endings: Unpacking 12 of History’s Most Infamous Automotive Disasters

The journey ‘Beyond the Dust Bowl’ reveals a history far richer and more intricate than often depicted. From the true catalysts of exodus and the harrowing journeys along Highway 66 to the profound socio-economic and cultural transformations witnessed in California, the story of the 1930s American migration is one of extraordinary resilience. The ‘Okies’ and ‘Arkies,’ often reviled and misunderstood, not only survived but actively shaped the landscape of their new home, leaving an enduring legacy of faith, plain-folk values, and an indelible mark on America’s musical and social fabric. Their story remains a poignant reminder of human endurance, a powerful symbol of the Great Depression’s impact, and a continuing testament to the complex, often challenging, journey towards the American dream.