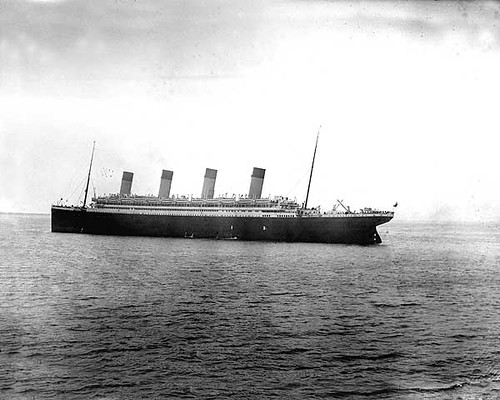

The RMS Titanic, a British ocean liner that set sail on its maiden voyage on April 10, 1912, from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States, represents a pinnacle of early 20th-century engineering ambition and luxury. Upon entering service, it stood as the largest ship afloat, a colossal testament to human ingenuity and a symbol of an era defined by grand industrial progress. This vessel, operated by the White Star Line, carried an eclectic mix of passengers, from the world’s wealthiest individuals to hundreds of emigrants seeking new lives across the Atlantic.

More than just a ship, the Titanic was conceived as a floating palace, boasting advanced safety features and unparalleled comfort that contributed to its widespread reputation as “unsinkable.” Its opulent first-class accommodations, featuring a gymnasium, swimming pool, and fine restaurants, promised a voyage of unprecedented grandeur. Yet, this symbol of human achievement was destined for a catastrophic encounter, striking an iceberg in the early hours of April 15, 1912, and plunging into the North Atlantic.

This in-depth chronicle will journey beyond the familiar headlines, offering a curated look at the ship’s extraordinary details, from its genesis and architectural marvel to its intricate deck layouts, luxurious provisions, and formidable propulsion systems. By exploring these foundational aspects, we can truly appreciate the magnitude of what was lost and the profound impact the Titanic’s story continues to have on our understanding of human endeavor and the forces of nature.

1. **The Vision: Genesis of the Olympic-Class Liners**The creation of the Titanic was born from a fierce competition for supremacy on the lucrative transatlantic passenger routes. The White Star Line faced a significant challenge from its main rivals, notably the Cunard Line, which had recently launched the swift twin sister ships *Lusitania* and *Mauretania*. These Cunard vessels, aided by the Admiralty, were the fastest passenger ships then in service, setting a high bar for speed and efficiency. German lines like Hamburg America and Norddeutscher Lloyd also added to the competitive pressure.

In response to this growing challenge, White Star Line’s chairman, J. Bruce Ismay, opted for a different strategy. Rather than competing solely on speed, Ismay proposed commissioning a new class of liners that would be unrivaled in size, comfort, and luxury. His vision was to create ships that would be “the last word in comfort and luxury,” providing an experience so superior that it would attract passengers even without breaking speed records. These new ships would also possess sufficient speed to maintain a weekly service with only three vessels, a more efficient operational model.

This ambitious plan took shape in a discussion in mid-1907 between Ismay and the American financier J. P. Morgan, whose International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMM) controlled the White Star Line’s parent corporation. The *Olympic* and *Titanic* were specifically intended to replace older White Star vessels such as the RMS *Teutonic* of 1889, RMS *Majestic* of 1890, and RMS *Adriatic* of 1907. This strategic move also coincided with the RMS *Oceanic* departing from a new home port in June 1907, along with the *Teutonic*, *Majestic*, and the new *Adriatic*, on the bustling Southampton-New York run.

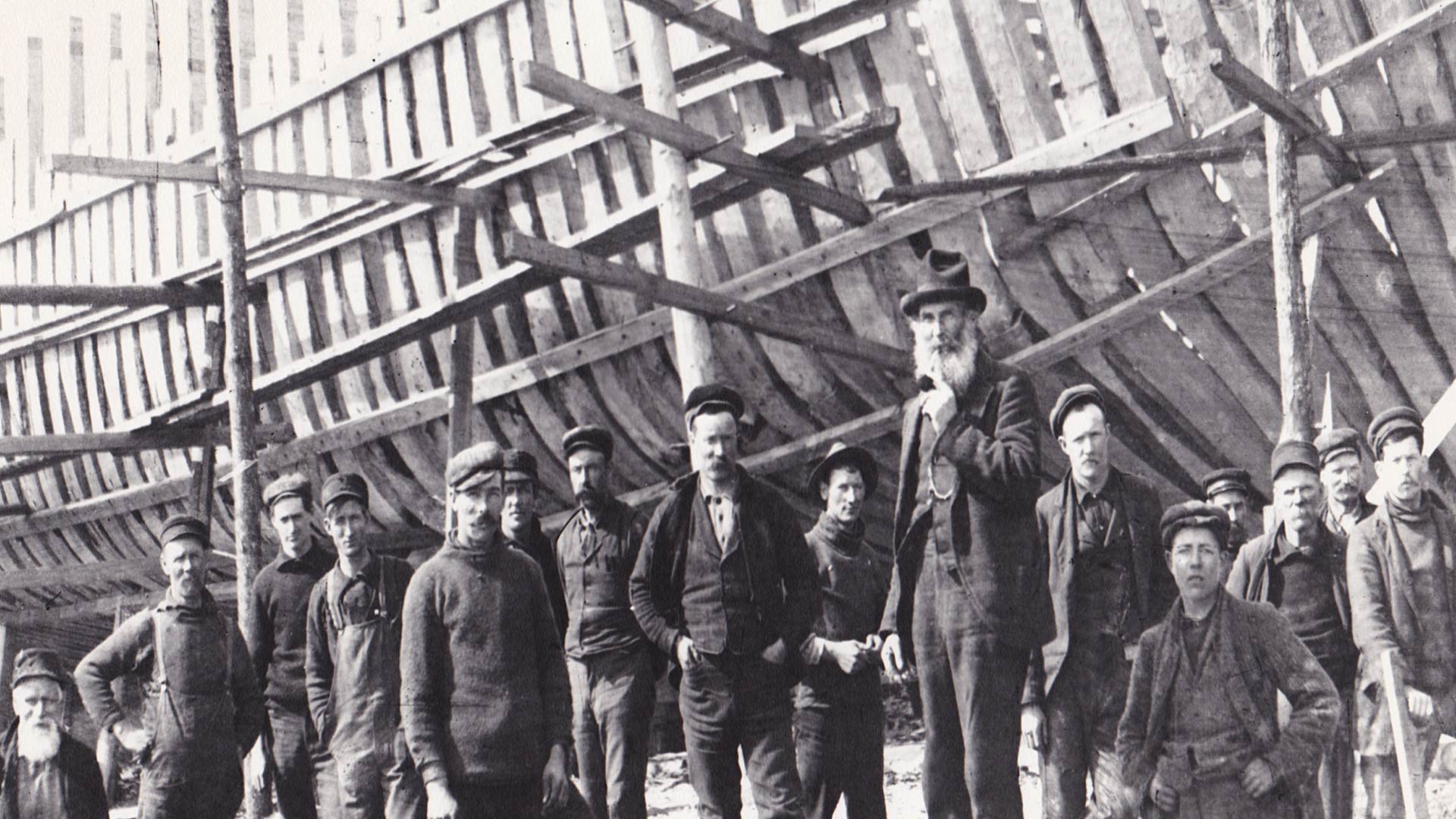

2. **Architectural Marvel: Harland & Wolff’s Masterpiece**The construction of these monumental liners was entrusted to the Belfast shipbuilder Harland & Wolff, a company with a long-established and trusted relationship with the White Star Line, dating back to 1867. This enduring partnership meant Harland & Wolff was granted considerable freedom in designing ships for White Star. The customary process involved Wilhelm Wolff sketching a general concept, which Edward James Harland would then transform into a detailed ship design, combining artistic vision with practical engineering.

Remarkably, cost considerations were a relatively low priority in the development of the *Olympic*-class ships. Harland & Wolff was authorized to expend whatever resources were necessary on the vessels, plus an additional five percent profit margin, underscoring White Star Line’s commitment to creating unparalleled ships. For the first two ships, a substantial cost of £3 million (equivalent to approximately £370 million in 2023) was agreed upon, along with “extras to contract” and the standard five percent fee, reflecting the scale of investment in this grand undertaking.

Harland & Wolff assembled their leading designers to bring the *Olympic*-class vessels to life. The design process was meticulously overseen by Lord Pirrie, who held directorships in both Harland & Wolff and the White Star Line, ensuring alignment between builder and owner. Key figures included naval architect Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland & Wolff’s design department, who tragically perished in the disaster. Edward Wilding, Andrews’s deputy, was responsible for crucial calculations regarding the ship’s design, stability, and trim. Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard’s chief draughtsman and general manager, was tasked with the decorations, equipment, and all general arrangements, notably including the implementation of an efficient lifeboat davit design.

On July 29, 1908, the meticulously prepared drawings were presented to J. Bruce Ismay and other White Star Line executives. Ismay promptly approved the design, signing three “letters of agreement” just two days later, thereby authorizing the commencement of construction. The first ship, which would eventually become the *Olympic*, was initially known simply as “Number 400,” signifying Harland & Wolff’s 400th hull. The *Titanic*, based on a refined version of this very same design, was subsequently designated as “Number 401,” each numeral marking a chapter in shipbuilding history.

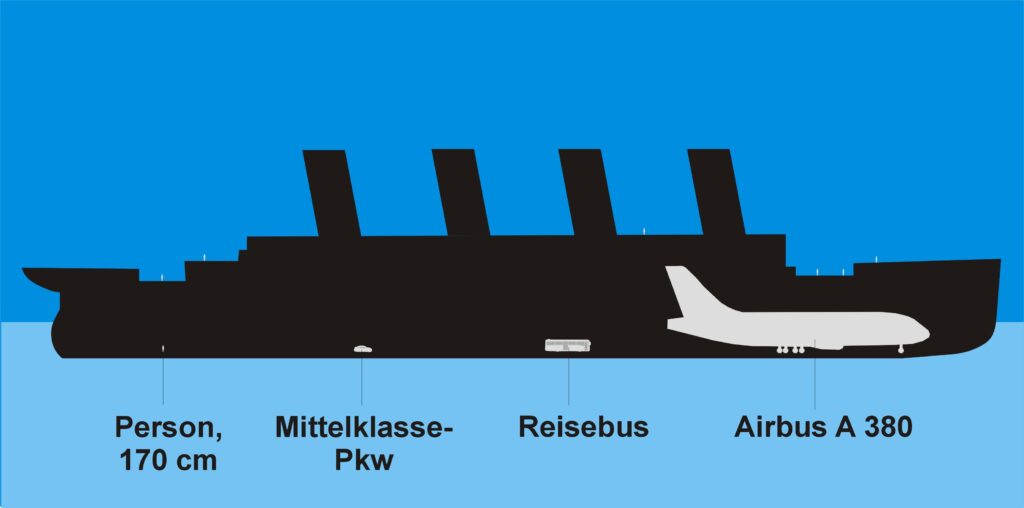

3. **A Giant Unveiled: Titanic’s Immense Dimensions**Upon its completion, the RMS Titanic was not merely a large ship; it was a behemoth, setting a new standard for maritime engineering and scale. Its sheer dimensions were a source of immense pride and confidence, contributing significantly to its reputation as a modern marvel. The vessel measured an astonishing 882 feet 9 inches (269.06 meters) in length overall, stretching almost a fifth of a mile. Its maximum breadth spanned an impressive 92 feet 6 inches (28.19 meters), showcasing a design that prioritized stability and interior space.

Measured from the base of its keel to the very top of its bridge, the ship’s total height reached 104 feet (32 meters), a towering structure that commanded attention. The Titanic boasted a gross registered tonnage (GRT) of 46,329 and a net registered tonnage (NRT) of 21,831, indicating its vast internal volume and cargo capacity. With a draught of 34 feet 7 inches (10.54 meters), the ship displaced an immense 52,310 tonnes of water, underscoring its massive weight and deep immersion.

These formidable statistics cemented the Titanic’s status as the largest ship afloat at the time of its entry into service. It was the second of three *Olympic*-class ocean liners, following its sister ship, the *Olympic*, and preceding the HMHS *Britannic*. Its monumental size was not just for show; it was a fundamental element of the White Star Line’s strategy to offer unparalleled comfort and luxury, allowing for expansive public rooms and lavish private accommodations previously unimaginable on the high seas.

4. **A Floating City: Decks and Their Distinctive Layouts**The Titanic was a meticulously designed vessel, featuring ten decks in total, eight of which were dedicated to passenger use, creating what truly felt like a floating city. These decks were carefully organized to segregate passengers by class and function, providing distinct experiences from the very top to the lowest levels.

The uppermost was the Boat Deck, named for the lifeboats housed along its sides. This crucial deck was where the ship’s lifeboats were tragically lowered into the North Atlantic in the early hours of April 15, 1912. The bridge and wheelhouse, vital for navigation, were situated at the forward end, directly in front of the captain’s and officers’ quarters. The bridge itself stood 8 feet (2.4 meters) above the deck, extending outwards to either side to facilitate docking maneuvers. Midships on the Boat Deck, passengers would find the entrance to the magnificent First Class Grand Staircase and the gymnasium, alongside the raised roof of the First Class lounge. At the rear were the roof of the First Class smoke room and the Second Class entrance. Intriguingly, just forward of the Second Class entrance were the kennels, accommodating the pampered dogs of First Class passengers. This wood-covered deck was further divided into four segregated promenades: one for officers, another for First Class passengers, one for engineers, and a separate one for Second Class passengers, ensuring distinct spaces for each group. A notable design choice was a gap in the lifeboats along the First Class area, deliberately created so that the view would not be spoiled.

Below the Boat Deck lay A Deck, also known as the Promenade Deck, which stretched along the entire 546-foot (166-meter) length of the superstructure. This deck was exclusively reserved for First Class passengers, providing expansive areas for strolling and socializing. It housed a significant number of First Class cabins, along with elegant public spaces such as the First Class reading and writing room, the main lounge, the smoke room, and the serene Palm Court, all designed to offer the utmost in sophisticated relaxation.

B Deck, or the Bridge Deck, served as the top weight-bearing deck and represented the uppermost level of the hull. Here, more First Class passenger accommodations were located, including six palatial staterooms that uniquely featured their own private promenades, offering an unprecedented level of privacy and luxury. On the Titanic, this deck was also home to the highly exclusive à la carte restaurant and the Café Parisien, both providing luxury dining facilities for First Class passengers. These venues were operated by subcontracted chefs and their staff, all of whom, tragically, were lost in the disaster. Additionally, the Second Class smoking room and entrance hall were both situated on B Deck.

The ship’s raised forecastle, positioned forward of the bridge deck, accommodated Number 1 hatch, which provided access to the cargo holds, as well as various machinery and the anchor housings. Aft of the bridge deck was the raised poop deck, a substantial 106 feet (32 meters) long, primarily used as a promenade by Third Class passengers. It was on this deck that many of the Titanic’s passengers and crew made their last stand as the ship succumbed to the icy waters. The forecastle and poop deck were distinctly separated from the central bridge deck by open well decks, contributing to the ship’s complex and stratified layout.

C Deck, designated as the Shelter Deck, was notable for being the highest deck to run uninterrupted from stem to stern, providing a continuous thoroughfare across the ship. It encompassed both well decks, with the aft well deck serving as an integral part of the Third-Class promenade area. Crew cabins were strategically housed below the forecastle at the bow, while Third-Class public rooms were located beneath the poop deck at the stern. In between these areas, the majority of First Class cabins were situated, along with the Second-Class library, highlighting the ship’s careful allocation of space across its various classes.

D Deck, known as the Saloon Deck, was characterized by three grand public rooms. These included the elegant First-Class reception room, the expansive First-Class dining saloon, and the functional Second-Class dining saloon, serving hundreds of passengers. The first- and second-class galleys, essential for feeding the ship’s population, were also conveniently located on this deck. An open space was provided for Third Class passengers, offering them an area for gathering. This deck also housed cabins for all three classes of passengers, with berths for firemen specifically located in the bow. Significantly, D Deck represented the highest level reached by the ship’s watertight bulkheads, though only eight of the fifteen bulkheads extended to this height, a detail that would prove critical in the disaster.

E Deck, the Upper Deck, was primarily dedicated to passenger accommodation for all three classes, offering a diverse array of cabins. Additionally, it provided berths for essential crew members including cooks, seamen, stewards, and trimmers, vital to the ship’s operation. Running along its considerable length was a lengthy passageway informally dubbed ‘Scotland Road,’ a direct reference to a famous street in Liverpool. This passageway served as a main artery for Third Class passengers and various crew members, facilitating movement across the ship’s lower levels.

F Deck, or the Middle Deck, predominantly accommodated Second- and Third-Class passengers, along with several departments of the crew. It was on this deck that the Third Class dining saloon was situated, serving the majority of emigrants aboard. Additionally, F Deck held a rather luxurious feature for First Class passengers: the bath complex, which included the ship’s impressive swimming pool and the opulent Victorian-style Turkish bath, offering a unique blend of amenities for different classes on the same level.

G Deck, the Lower Deck, was unique for having the lowest portholes, positioned just above the waterline. This deck housed the first-class squash court, a novel recreational amenity. It was also home to the travelling post office, where five postal clerks diligently sorted up to 60,000 items daily, preparing letters and parcels for delivery upon arrival. Furthermore, food supplies for the entire ship were extensively stored here. The deck was punctuated at several points by orlop (partial) decks, which extended over the vital boiler, engine, and turbine rooms, indicating the integration of machinery within the ship’s lower passenger areas.

The very lowest levels of the ship, below the waterline, consisted of the orlop deck and the tank top. The tank top, named for the water and ballast tanks stored in the ship’s double bottom, formed the inner bottom of the hull and served as the platform for the Titanic’s boilers, engines, turbines, and electrical generators. This machinery-intensive area was strictly prohibited to passengers. Access to these critical sections from higher levels was provided by two flights of stairs in the fireman’s passage, alongside twin spiral stairways near the bow that led up to D Deck, and ladders in the boiler, turbine, and engine rooms themselves.

5. **Pinnacle of Opulence: First-Class Luxury and Amenities**The passenger facilities aboard the Titanic were meticulously designed to embody the highest standards of luxury, setting a new benchmark for ocean travel. Departing from the traditional décor of other passenger liners, which often mimicked a manor house or English country house, the Titanic’s interior design adopted a lighter, more contemporary style. The Ritz Hotel, a renowned symbol of high-class hospitality, served as a key reference point for its design philosophy, with First Class cabins finished in the elegant Empire style.

A rich variety of decorative styles, ranging from the grandeur of the Renaissance to the refined aesthetics of Louis XV, were artfully employed throughout the cabins and public rooms in both First and Second Class areas. The overarching goal was to create an immersive experience, making passengers feel as though they were in a floating hotel rather than on a ship. As one passenger vividly recalled, upon entering the ship’s interior, one would “at once lose the feeling that we are on board ship, and seem instead to be entering the hall of some great house on shore.” Adding to the convenience, First Class cabins were equipped with buttons that, when pressed, would signal for a steward to provide immediate service.

Among the more innovative features exclusively available to First Class passengers was a generous 7-foot (2.1-meter) deep saltwater swimming pool, a fully equipped gymnasium for physical recreation, and a squash court. For relaxation and rejuvenation, a Victorian-style Turkish bath complex was provided, comprising a hot room, a warm (temperate) room, a cooling-room, and two shampooing (massage) rooms. Complementing the Turkish bath and within the same luxurious area, there was also a steam room and an electric bath, offering a full suite of wellness facilities.

First-class common rooms were not only impressive in their scope but also lavishly decorated, reflecting an air of exclusive sophistication. These included a grand lounge designed in the exquisite style of the Palace of Versailles, an enormous reception room perfect for social gatherings, a refined men’s smoking room, and a quiet reading and writing room. For dining, an à la carte restaurant, conceptualized in the style of the Ritz Hotel, was run as a concession by the famous Italian restaurateur Gaspare Gatti. Annexed to this restaurant was the delightful Café Parisien, decorated to resemble a French pavement café, complete with ivy-covered trellises and charming wicker furniture. For an additional cost, First Class passengers could indulge in the finest French haute cuisine amidst these most luxurious of surroundings.

Further enhancing the First Class experience was a Verandah Café, where tea and light refreshments were served, offering magnificent views of the ocean. The sheer scale of the dining facilities was exemplified by the dining saloon on D Deck, designed by Charles Fitzroy Doll. Measuring an impressive 114 feet (35 meters) long by 92 feet (28 meters) wide, it was proudly the largest room afloat and could comfortably seat almost 600 passengers at a time, facilitating grand communal meals.

Perhaps one of the Titanic’s most iconic and distinctive features was the First Class staircase, universally known as the Grand Staircase or Grand Stairway. This architectural masterpiece, constructed of solid English oak with a graceful sweeping curve, descended through an astonishing seven decks of the ship, from the Boat Deck down to E Deck, before concluding in a more simplified single flight on F Deck. It was crowned with an elaborate dome of wrought iron and glass, ingeniously designed to admit abundant natural light into the entire stairwell, creating a breathtaking visual spectacle. Each landing off the staircase provided access to ornate entrance halls, beautifully paneled in the distinguished William & Mary style and elegantly illuminated by ormolu and crystal light fixtures. At the uppermost landing, a large carved wooden panel prominently featured a clock, flanked by allegorical figures of “Honour and Glory Crowning Time,” adding a classical touch to its already profound grandeur. Tragically, the Grand Staircase was destroyed during the sinking, leaving only a void in the ship’s structure, a poignant reminder of its former splendor. It has been theorized that during the actual event, the entire Grand Staircase was forcefully ejected upwards through its dome due to the immense pressure of the inrushing water.

6. **Beyond Steerage: Second and Third-Class Comforts**While the First Class accommodations epitomized luxury, the Second and Third Class provisions aboard the Titanic represented a significant departure from the harsh conditions commonly found on other ships of the era. White Star Line had long been at the forefront of improving conditions for all passengers, moving away from the typical perception of “steerage” as merely open dormitories where hundreds were confined without adequate food or sanitation.

Specifically, Third Class accommodations, though not as lavish as First or Second Class, were notably superior to many contemporary vessels. White Star Line ships, including the Titanic, thoughtfully divided their Third Class areas into two distinct sections, strategically placed at opposite ends of the vessel. This arrangement ensured that single men were quartered in the forward areas, while single women, married couples, and families were provided accommodations aft, addressing concerns of privacy and propriety.

Breaking another industry norm, White Star Line vessels did not force their Third Class passengers into open berth sleeping arrangements. Instead, they offered private, small but comfortable cabins, capable of accommodating two, four, six, eight, and even ten passengers. This provision of private sleeping quarters, however modest, was a considerable improvement, offering a degree of personal space and dignity previously uncommon for emigrants and those traveling in lower classes.

Beyond sleeping arrangements, Third Class accommodations also included their own dedicated dining rooms, providing proper meal services. Crucially, they were also allocated public gathering areas, including adequate open deck space for recreation and fresh air, a stark contrast to the cramped conditions often found elsewhere. These amenities were further supplemented by the addition of a smoking room specifically for men and a general room on C Deck, which women could utilize for reading and writing, fostering a sense of community and providing essential leisure options.

For Second Class passengers, the amenities were a step up, though still distinct from the First Class experience. They enjoyed their own dining saloon on D Deck, a smoking room on B Deck, and access to a dedicated library on C Deck, providing comfort and social spaces. The design intent was to provide a very high standard of travel that rivaled the First Class offerings on many other transatlantic liners.

Leisure facilities were, in varying degrees, provided for all three classes, allowing passengers to pass the time during the lengthy voyage. Beyond utilizing the ship’s indoor amenities such as the libraries, smoking rooms, and gymnasium, it was customary for passengers across classes to socialize on the open deck. They would engage in promenading or simply relax in hired deck chairs or on wooden benches, enjoying the sea air. Adding to the social dynamics of the voyage, a passenger list was published before the sailing, informing the public of prominent individuals on board. It was not uncommon for ambitious mothers to scrutinize this list, identifying affluent bachelors to whom they might introduce their marriageable daughters during the journey, highlighting the ship’s role as a social microcosm.

7. **Engineering Prowess: Power, Propulsion, and the Men Who Fed Its Fires**The immense power required to propel the Titanic across the Atlantic was a marvel of early 20th-century marine engineering. Its propulsion system relied on a sophisticated combination of three main engines. This included two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion steam engines, paired with one centrally placed low-pressure Parsons turbine. Each of these engines drove a separate propeller, creating a robust and efficient propulsion mechanism.

The two reciprocating engines delivered a formidable combined output of 30,000 horsepower (22,000 kW), providing the primary thrust. The steam turbine, situated aft, contributed an additional 16,000 horsepower (12,000 kW), demonstrating the significant cumulative power of the system. This particular combination of engines had been successfully employed by the White Star Line on an earlier liner, the *Laurentic*, where it proved to be a great success. This hybrid system offered an optimal balance of performance and speed; reciprocating engines alone were not potent enough to drive an *Olympic*-class liner at its desired speeds, while all-turbine systems, though powerful, generated uncomfortable vibrations, a notable issue that affected Cunard’s *Lusitania* and *Mauretania*. By integrating reciprocating engines with a turbine, the Titanic achieved reduced fuel usage and increased motive power while efficiently utilizing the same amount of steam, showcasing a thoughtful engineering solution.

At the heart of this power system were the massive boilers and the constant demand for coal. The two reciprocating engines, each measuring 63 feet (19 meters) long and weighing 720 tonnes (with their bedplates adding another 195 tonnes), were powered by steam generated in 29 boilers. Of these, 24 were double-ended and five were single-ended, containing a total of 159 furnaces. Each boiler was a substantial 15 feet 9 inches (4.80 meters) in diameter and 20 feet (6.1 meters) long, weighing 91.5 tonnes and capable of holding 48.5 tonnes of water, underscoring the scale of the ship’s internal machinery.

The furnaces consumed an enormous amount of coal, with over 600 tonnes required daily to be shoveled into them by hand. This relentless task demanded the services of 176 firemen working around the clock in shifts, a physically grueling and continuous operation. The waste product, approximately 100 tonnes of ash each day, had to be disposed of by ejecting it into the sea, highlighting the intense industrial activity beneath the passenger decks. The work of the firemen was described as “relentless, dirty and dangerous,” and despite being relatively well-paid, there was a tragically high suicide rate among those who served in this capacity.

Exhaust steam, having passed through the reciprocating engines, was then fed into the turbine, positioned towards the aft of the ship. From the turbine, it proceeded into a surface condenser, a crucial component that not only increased the turbine’s efficiency but also condensed the steam back into water for reuse, an early form of energy recycling. The engines were directly connected to long shafts, which in turn drove the ship’s three propellers. The two outer, or “wing,” propellers were the largest, each featuring three blades made of manganese-bronze alloy and boasting a total diameter of 23.5 feet (7.2 meters). The middle propeller was slightly smaller, at 17 feet (5.2 meters) in diameter, and notably, could be stopped but not reversed, a unique operational characteristic.

Beyond propulsion, the Titanic’s electrical plant was impressively robust, capable of producing more power than an average city power station of the time. Situated immediately aft of the turbine engine were four 400 kW steam-driven electric generators, responsible for supplying electrical power throughout the vessel. Additionally, two 30 kW auxiliary generators were on standby for emergency use. The strategic location of these generators in the stern of the ship proved significant, as they remained operational until the very last few minutes before the ship ultimately sank, providing power until almost the final moments. The ship, however, lacked a searchlight, in accordance with the ban on their use in the merchant navy at the time.

8. **Ingenious Safeguards: Watertight Compartments and Advanced Systems**Beneath the Titanic’s opulent decks lay a complex array of technologies designed to ensure safety, underpinning its “unsinkable” reputation. The ship’s internal structure was divided into 16 primary compartments by 15 bulkheads, extending significantly above the waterline to contain flooding. This extensive compartmentalization was a cornerstone of its design, aimed at maintaining buoyancy even if parts of the hull were compromised.

Eleven vertically closing watertight doors on the orlop deck provided critical additional security. These doors could be activated by a switch on the bridge, a local lever, or an automatic buoyancy mechanism if water reached six feet within a compartment. This multi-layered control system represented cutting-edge engineering for rapid isolation of flooded areas, demonstrating a robust approach to managing potential breaches.

Beyond internal safeguards, the ship’s exterior featured four striking funnels, though only three were functional. The aftmost funnel was purely aesthetic, enhancing the ship’s grand profile while ingeniously providing ventilation to kitchens and smoking rooms. Towering 155-foot (47-meter) masts supported derricks for cargo handling, highlighting the Titanic’s dual role as a luxury liner and a commercial vessel.

Maneuvering such a colossal ship required an equally formidable steering mechanism. The Titanic’s rudder, weighing over 100 tonnes, necessitated two steam-powered steering engines, one active and one in reserve. These engines connected to the tiller via stiff springs, designed to absorb shocks from heavy seas. As a last resort, ropes connected to steam capstans could move the tiller, these same capstans also managing the ship’s five anchors. The vessel also included an intricate waterworks system and an advanced ventilation network.

9. **The Lifeline to Shore: Radiotelegraphy on the Titanic**In the early 20th century, wireless telegraphy, or “Marconi,” was the critical link for ships at sea. The Titanic’s state-of-the-art radiotelegraph system, operated by Marconi Company employees Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, maintained a crucial 24-hour schedule. This service was vital for both sending and receiving passenger “marconigrams”—personal telegrams connecting those aboard with the outside world—and handling essential navigation messages, including weather reports and ice warnings.

The wireless room, strategically located on the Boat Deck within the officers’ quarters, was the nerve center of this operation. A soundproofed “Silent Room” housed the powerful 5-kilowatt rotary spark-gap transmitter and its motor-generator, ensuring operational efficiency. The operators’ living quarters were conveniently adjacent, allowing for continuous staffing and prompt response to communications.

The Titanic’s transmitter was renowned as one of the most powerful globally, boasting a guaranteed broadcast radius of 350 miles (563 km), and a distinctive musical tone for its Morse code signals. An elevated T-antenna, spanning the ship’s length, optimized transmitting and receiving. Operating primarily on a 500 kHz frequency, it could switch to 1,000 kHz for smaller vessels. This robust and continuously monitored wireless facility was envisioned as a significant safety asset, a critical means of calling for assistance should the unforeseen ever occur.

10. **Beyond Baggage: Mail, Cargo, and Hidden Valuables**While the Titanic epitomized luxury passenger travel, it also played a significant commercial role as a Royal Mail Ship (RMS), carrying mail for the Royal Mail and the U.S. Post Office Department. A substantial 26,800 cubic feet (760 cubic meters) of space was dedicated to letters, parcels, and specie. On G Deck, five postal clerks—three Americans and two Britons—worked 13-hour shifts, sorting up to 60,000 items daily for transatlantic delivery.

Beyond official mail, the ship transported vast quantities of personal baggage, with 19,455 cubic feet (550.9 cubic meters) allocated to First and Second Class luggage. The cargo manifest also included a considerable range of commercial goods, from furniture and foodstuffs to unique items like ostrich feathers, “Dragon’s Blood” resin, and a 1912 Renault Type CE Coupe de Ville motor car, symbolizing emerging automotive luxury.

Despite popular myths of hidden treasures, the bulk of the Titanic’s cargo was largely mundane. There were no vast riches of gold or diamonds, though a jeweled copy of the *Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam* was valued at £405 (£50,600 today). However, post-sinking claims revealed significant individual losses; First-Class passenger Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson filed a $100,000 claim (equivalent to $2,300,000 in 2024) for *La Circassienne au Bain* by Merry-Joseph Blondel. To manage this diverse freight, the Titanic utilized eight electric cranes and several winches, underscoring its substantial commercial capacity.

11. **Lifeboats and the Illusion of Safety: A Regulatory Oversight**The “unsinkable” reputation of the Titanic fostered a critical flaw in its safety provisions: an inadequate number of lifeboats. Although the ship boasted 16 sets of davits capable of deploying 48 lifeboats, White Star Line chose to carry only 20—14 standard wooden and four Engelhardt collapsibles—sufficient for just 1,178 people. This figure represented a mere one-third of the ship’s total capacity for passengers and crew, a stark deficiency brutally exposed by the ensuing disaster.

Each of the 14 standard lifeboats held 65 people, while the four collapsibles and two emergency cutters accommodated 47 and 40 individuals, respectively. These boats were carefully stowed on the Boat Deck, with two cutters kept perpetually ready. However, collapsible lifeboats A and B, stored on the officers’ quarters roof without davits, proved exceptionally difficult to deploy during the crisis. Despite these limitations, each boat was provisioned with essentials like food, water, blankets, and a spare life belt.

Ironically, the Titanic’s lifeboat provision actually exceeded the legal requirements of the time. British Board of Trade regulations only mandated 16 lifeboats for ships over 10,000 tonnes, providing capacity for 990 occupants. Thus, White Star technically surpassed the minimum. This compliance with flawed regulations underscored a profound misjudgment: lifeboats were then intended to ferry survivors to a rescuing ship, not to evacuate an entire vessel. This critical assumption, coupled with nearby ships failing to respond, tragically highlighted a regulatory philosophy ill-equipped for such a catastrophe.

12. **The Human Element: Crew and Passengers Facing the Inevitable**The RMS Titanic was more than engineering; it was a floating tapestry of human lives, carrying an estimated 2,224 souls. This diverse community included the world’s wealthiest individuals alongside hundreds of European emigrants, all pursuing new beginnings. Their collective journey tragically concluded for approximately 1,500, transforming the ship into a poignant symbol of human vulnerability against nature.

Prominent figures aboard included Captain Edward John Smith, the revered commander who went down with his ship. Thomas Andrews Jr., the brilliant chief naval architect, also perished, remaining steadfast. Conversely, J. Bruce Ismay, the White Star Line chairman, controversially survived, later facing intense public scrutiny. These individual stories highlight the varying experiences and fates caught in the disaster.

The ship’s operation relied heavily on its dedicated crew. The 176 firemen endured “relentless, dirty and dangerous” conditions, manually shoveling over 600 tonnes of coal daily into the boilers. Despite good pay, the grueling nature led to a tragically high suicide rate. Similarly, five postal clerks tirelessly sorted up to 60,000 mail items daily, continuing their duties even as the ship faced its end.

For First-Class passengers, the voyage was also a significant social event. Passenger lists were eagerly consulted by ambitious mothers identifying affluent bachelors for their daughters, underscoring the ship’s role as a grand social stage. These personal narratives, spanning all classes and roles, paint a vivid picture of the human dimension of the Titanic’s tragedy, making its loss profoundly relatable across generations.

13. **The Fatal Encounter: The Iceberg and the Unforeseen Catastrophe**The RMS Titanic, a vessel once synonymous with impregnable design, met its unforeseen destiny in the early hours of April 15, 1912. On its maiden voyage, a catastrophic collision with an iceberg plunged this symbol of human achievement into the depths of the North Atlantic. This sudden, violent impact initiated a chain of events that exposed inherent vulnerabilities, profoundly challenging the prevailing confidence in modern engineering.

Despite its lauded watertight compartments, the Titanic possessed a critical design flaw: only eight of its fifteen bulkheads extended to D Deck. This meant that if sufficient forward compartments were breached, water could cascade over these lower bulkheads into adjacent sections, effectively circumventing the intended safety barrier. The iceberg’s lengthy gash along the starboard side proved to be precisely this kind of extensive damage, overwhelming the ship’s ability to contain the ingress of water.

The immense forces unleashed during the sinking also had a devastating effect on the ship’s internal grandeur. It is theorized that the iconic First-Class Grand Staircase was forcefully ejected upwards through its magnificent glass dome by the sheer pressure of the surging water. This detail speaks to the violent and uncontrollable nature of the ship’s final moments, where even its most robust interior structures were torn apart by the ocean’s unforgiving power.

Remarkably, some of the ship’s core systems persevered almost to the very end. The robust electrical plant, housed in the stern, continued to supply power, keeping lights illuminated and critical functions operational for much of the disaster. This sustained power allowed for ongoing communication and a semblance of order amidst the growing chaos. Ultimately, the collision led to the tragic loss of approximately 1,500 lives, shattering the illusion of the “unsinkable” and prompting a global re-evaluation of maritime safety.

14. **A Legacy Etched in Ice: Maritime Safety and Cultural Impact**The sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912, was a cataclysmic event that transcended tragedy, becoming a pivotal moment in maritime history and deeply influencing global culture. The immense loss of approximately 1,500 lives—from the ship’s esteemed captain, Edward John Smith, and its chief designer, Thomas Andrews Jr., to hundreds of immigrants—spurred an immediate and urgent re-evaluation of safety standards across the world’s oceans.

A paramount outcome was the complete overhaul of lifeboat regulations. The Titanic, though meeting existing legal requirements, carried lifeboats for only a third of its total complement. This shocking deficiency prompted a universal mandate: all ships must carry sufficient lifeboat capacity for every person onboard. This fundamental shift redefined maritime safety, moving from merely ferrying survivors to ensuring direct salvation for all.

The disaster also highlighted critical shortcomings in sea communication. Issues like operator fatigue and the overwhelming volume of non-essential “marconigrams” hindering distress calls became glaringly apparent. This led to the 1914 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), which mandated 24-hour radio watch on passenger ships and required backup power for wireless equipment, revolutionizing oceanic communication protocols.

Furthermore, the sinking instigated the establishment of the International Ice Patrol, dedicated to tracking icebergs in the North Atlantic and broadcasting warnings. This crucial preventative measure directly addressed the cause of the Titanic’s demise, significantly reducing the risk of similar collisions. These sweeping reforms, born from profound tragedy, fundamentally transformed shipbuilding and operational practices, making ocean travel vastly safer for future generations.

Read more about: The Unsinkable Dream: Exploring the Opulent World and Cutting-Edge Engineering of the RMS Titanic

Beyond its regulatory impact, the Titanic’s story embedded itself deeply into the global consciousness. It serves as a potent allegory for human hubris, the stark social divisions of the era, and the ultimate fragility of even the most advanced technology when confronted by nature’s unyielding power. Through countless books, films, and documentaries, the narrative continues to captivate, ensuring its lessons echo through history, a timeless reminder whispered by the cold North Atlantic waves.