The story of the United States is one of relentless evolution, a continuous interplay of foundational principles, vast geographical expansion, profound societal challenges, and an unyielding drive toward innovation. From its nascent beginnings as a collection of colonies to its current status as a global superpower, America has consistently demonstrated a capacity for transformation, adapting its structures and leveraging its strengths to navigate complex historical currents. This enduring spirit of change and progress, deeply embedded in its historical fabric, sets a compelling precedent for any future ‘resurgence,’ be it in manufacturing or other sectors.

Indeed, when we consider the intricate tapestry of American history, we uncover a recurring pattern: moments of crisis invariably give way to periods of intense re-evaluation and subsequent advancement. This trajectory is not merely a chronicle of events but a testament to a national character defined by its adaptability, its embrace of new frontiers—both physical and technological—and its persistent pursuit of betterment, even amidst significant internal and external pressures. Understanding these deep-seated characteristics, meticulously documented through centuries of development, offers crucial insights into the underlying forces that continue to empower the nation’s forward momentum.

As we embark on this in-depth analysis, we will explore key epochs and defining attributes of the United States, viewed through a ‘Wired’ lens that emphasizes critical thought, technological underpinnings, and future implications. These are the intrinsic elements, forged in the crucible of history, that underscore America’s unique potential to not just adapt, but to lead in new industrial revolutions, harnessing its inherent dynamism to power future advancements.

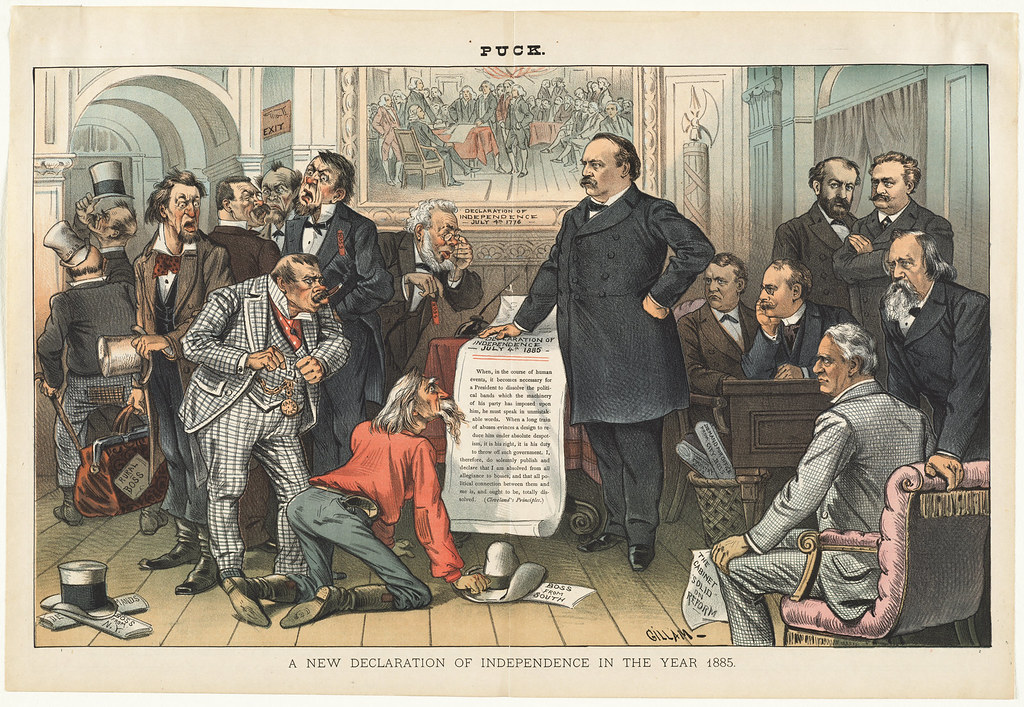

1. **Foundational Principles of the American Republic: The Blueprint for a Dynamic Nation**

The birth of the United States was a revolutionary act, a deliberate design to establish a new form of governance rooted in Enlightenment ideals. The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, articulated radical notions of “liberty, inalienable individual rights; and the sovereignty of the people.” This document not only severed ties with the British Crown but laid down the philosophical bedrock for a nation where power would ultimately reside with its citizens. The subsequent victory in the 1775–1783 Revolutionary War cemented these ideals, providing international recognition of U.S. sovereignty and setting the stage for a unique political experiment.

The U.S. Constitution, drafted in 1787 and going into effect in 1789, further refined this experiment, creating a “federal republic governed by three separate branches that together formed a system of checks and balances.” This intricate separation of powers – legislative, executive, and judicial – was designed to prevent any single branch from becoming supreme, fostering a dynamic equilibrium within the government. The adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 addressed early concerns about governmental power, enshrining fundamental freedoms and protections for individuals, which remain central to American identity.

These foundational principles – republicanism, individual liberty, and a system of checks and balances – have created an environment uniquely conducive to innovation and progress. By fostering a framework where individual enterprise is valued and political power is distributed, the early republic established conditions that could theoretically accommodate profound economic and technological shifts. This democratic tradition, inspired by the American Enlightenment movement, provides a stable yet adaptable scaffolding upon which future advancements could be built, encouraging a societal predisposition towards questioning the status quo and striving for improvement.

Beyond mere political structure, the emphasis on civic virtue and the “vilification of political corruption” championed by the Founding Fathers instilled a moral dimension into the national psyche. This ideological commitment to a self-governing people, even with its historical imperfections, has cultivated a society capable of sustained self-reflection and recalibration. Such a robust ideological framework is not just historical detail; it represents a deep-seated institutional capacity for renewal and adaptation, which is vital for any long-term national ‘resurgence.’

2. **Westward Expansion and the Shaping of a Continent: Fueling Growth and Resource Acquisition**

From the late 18th century, a powerful sense of “manifest destiny” propelled American settlers westward, dramatically transforming the nation’s physical and economic footprint. The monumental “Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France nearly doubled the territory of the United States,” representing an unparalleled acquisition of land and natural resources. This rapid geographical expansion was not just about increasing acreage; it was about securing a continental expanse that would become the engine of future industrial and agricultural might, providing vast tracts for development and a wealth of raw materials.

However, this expansion was not without profound ethical complexities, illustrating the ‘critical and thought-provoking’ aspects of American history. As Americans moved into territories inhabited by Native Americans, the federal government implemented policies of “Indian removal or assimilation.” The “Indian Removal Act of 1830,” a key policy of President Andrew Jackson, led to the tragic “Trail of Tears (1830–1850), in which an estimated 60,000 Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River were forcibly removed and displaced to lands far to the west, causing 13,200 to 16,700 deaths along the forced march.” This dark chapter underscores the human cost embedded within the nation’s growth narrative.

Despite these profound moral failings, the sheer scale of territorial acquisition continued. “Spain ceded Florida and its Gulf Coast territory in 1819,” followed by the annexation of “the Republic of Texas in 1845.” The “1846 Oregon Treaty led to U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest,” and the “1848 Mexican Cession” after the Mexican–American War added vast lands including New Mexico and California. This relentless westward drive established the U.S. as a continental power, rich in varied landscapes and resources, from fertile plains to mineral-rich mountains, laying the material foundation for industrialization.

The continuous expansion, though often brutal, profoundly influenced the American psyche, fostering a narrative of boundless possibility and perpetual frontier. This mindset, rooted in the literal conquest of a continent, arguably imbued the nation with an inherent drive for growth and exploration, traits that would later manifest in technological and economic ambitions. The very act of carving out such a vast and diverse nation from wilderness and existing settlements speaks to a powerful organizational and developmental impetus that, when channeled, can drive significant ‘resurgence’ in any given era.

3. **The American Civil War and National Unity: A Defining Test of Resolve**

The fundamental contradiction of a nation founded on liberty that simultaneously embraced slavery ultimately erupted into the American Civil War (1861–1865), a conflict that remains the most profound internal struggle in U.S. history. The deep-seated “North–South division over slavery” had roots in economic disparity; by 1770, slavery “supplied most of the labor for the Southern Colonies’ plantation economy,” a system that became immensely profitable with the widespread use of inventions like the cotton gin. While Northern states began to prohibit slavery, support for it strengthened in the South, setting the nation on an inexorable collision course.

This simmering tension boiled over in 1861 when 11 slave-state governments, beginning with South Carolina, “voted to secede from the United States,” forming the Confederate States of America. The war commenced with the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, pitting brother against brother in a fight for the nation’s soul. President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, transformed the war into a moral crusade against slavery, leading “many freed slaves [to join] the Union army” and fundamentally altering the conflict’s stakes.

The Union’s victory in 1865, culminating in the surrender at Appomattox Court House, resulted in the reunification of the country and the national abolition of slavery. This outcome was not merely a military triumph but a profound redefinition of the American experiment, affirming the indivisibility of the Union and moving, albeit slowly and imperfectly, toward a more just society. The war’s aftermath saw the ratification of three “Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution” – the 13th abolished slavery, the 14th promised “equal protection under the law for all persons,” and the 15th prohibited “discrimination on the basis of race or previous enslavement.” These amendments, though their force was later undermined, represented a critical, albeit incomplete, step toward a truly inclusive republic.

The Civil War, a period of immense devastation and social upheaval, ultimately reinforced the concept of national unity and demonstrated the nation’s capacity for self-correction under extreme pressure. The abolition of slavery, despite the long shadow of subsequent racial discrimination, removed a fundamental moral and economic impediment to a truly modern industrial society. The sheer scale of mobilization and technological improvisation during the war itself hinted at an underlying industrial and innovative capacity that would be unleashed in the decades that followed, underscoring a resilient national character capable of enduring and recovering from its most severe internal divisions.

Read more about: The ’70s Puzzle: 12 Lost Giants – Why These American and Global ‘Trucks’ Vanished from the Roads of History

4. **The Gilded Age: A Crucible of Industrial and Technological Transformation**

The period from the mid-19th to early 20th century, often termed the Gilded Age, witnessed an “explosion of technological advancement accompanied by the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor” that fueled “rapid economic expansion.” This era was a pivotal moment in America’s industrial ascent, allowing it to “outpace the economies of England, France, and Germany combined.” It was a time when the foundational elements of a modern industrial economy were forged, characterized by massive infrastructure projects and new modes of production.

This transformative era saw the rise of powerful industrialists, or tycoons, who spearheaded the nation’s growth in vital sectors. These figures led expansion in the “railroad, petroleum, and steel industries,” establishing the logistical and material backbone for unprecedented economic activity. Furthermore, “The United States emerged as a pioneer of the automotive industry,” signaling its capacity to not just adopt but to lead in the development of cutting-edge technologies that would reshape global commerce and daily life. The concentration of wealth and power through “trusts and monopolies to prevent competition” was a defining, albeit controversial, feature of this period.

However, this rapid industrialization and unchecked capitalism also brought forth significant societal challenges, providing a ‘critical and thought-provoking’ dimension to this narrative. The context notes “significant increases in economic inequality, slum conditions, and social unrest,” which led to the flourishing of “labor unions and socialist movements.” This dual nature of progress – immense wealth and technological leaps alongside widespread social distress – is a crucial lesson in the complexities of rapid development. It highlights the constant tension between economic efficiency and social equity, a balance that any nation undergoing a ‘resurgence’ must contend with.

Ultimately, the Gilded Age laid the irreversible groundwork for America’s industrial might. The technological breakthroughs, the establishment of massive industries, and the sheer scale of economic growth during this period demonstrated an unparalleled capacity for innovation and production. Even with its social costs, this era provided the industrial infrastructure, the capital accumulation, and the entrepreneurial spirit that would continue to define American economic power for generations, proving that the nation possessed the raw ingredients for profound ‘manufacturing resurgence’ should conditions align.

Read more about: The Unseen Lens: Unpacking the Global Forces That Gave the 1990s Its Distinctive and Pervasive ‘Look’

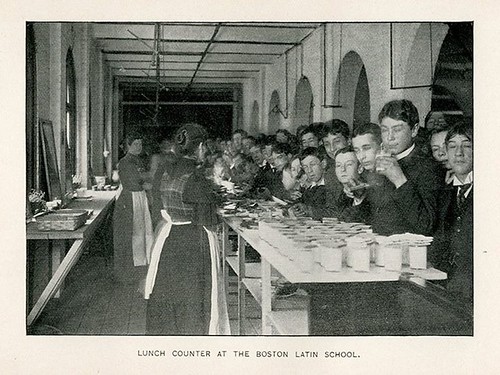

5. **Immigration and the Forging of a Diverse Nation: A Continuous Wellspring of Labor and Culture**

America’s story is inextricably linked to immigration, a continuous process that has profoundly shaped its demographics, culture, and economy. From “1865 through 1917, an unprecedented stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, including 24.4 million from Europe.” This massive influx, primarily flowing through the Port of New York, led to significant demographic shifts, with “New York City and other large cities on the East Coast [becoming] home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations.” Simultaneously, “Many Northern Europeans as well as significant numbers of Germans and other Central Europeans moved to the Midwest,” populating and developing the nation’s heartland.

Beyond European arrivals, other significant migrations contributed to America’s rich tapestry. “About one million French Canadians migrated from Quebec to New England,” further diversifying the regional cultural landscape. Domestically, the “Great Migration” saw “millions of African Americans left the rural South for urban areas in the North,” seeking economic opportunity and escaping oppressive conditions. This internal movement reshaped Northern cities and laid the groundwork for future social and political movements, adding another layer to the nation’s complex demographic evolution.

This continuous stream of immigration was a critical engine for America’s economic expansion, particularly during periods of industrial growth. The availability of diverse labor, often willing to work in challenging conditions, fueled the factories and infrastructure projects that underpinned the nation’s rise. While the context explicitly mentions “exploitation of cheap immigrant labor” during the Gilded Age, it also implicitly highlights the immense human capital and cultural vibrancy that these populations brought. This dynamic interaction of labor, culture, and opportunity has consistently renewed and diversified the American workforce and consumer base.

The cumulative effect of centuries of immigration has been the creation of a “diverse and globally influential” culture. This cultural diversity, a constant feature since the earliest European settlements and further enriched by Indigenous peoples, has fostered a unique societal dynamism. The blending of traditions, ideas, and skills from around the world has arguably contributed to America’s innovative capacity, providing varied perspectives and a relentless drive for opportunity that is essential for any form of national ‘resurgence.’

6. **The Progressive Era: Adapting to Modernity and Setting Precedents for Reform**

Emerging as a direct response to the glaring social and economic disparities of the Gilded Age, the Progressive Era was characterized by “significant reforms” aimed at addressing the profound challenges of industrial society. The unchecked accumulation of wealth by industrialists, coupled with “economic inequality, slum conditions, and social unrest,” necessitated a period of national introspection and systemic change. This era represented a crucial phase of societal adaptation, where the nation grappled with the consequences of its rapid industrialization and sought to refine its commitment to democratic principles.

One of the landmark achievements of the Progressive Era was the expansion of democratic participation through “a constitutional amendment [that] granted nationwide women’s suffrage” in 1920. This monumental shift not only brought millions of women into the political fold but also symbolized a broader recognition of individual rights and a move toward a more inclusive vision of American democracy. Such reforms were indicative of a societal willingness to challenge established norms and push for greater equity, reflecting a maturing national consciousness that could self-correct through legislative action.

The era also saw a heightened focus on addressing the harsh realities of urban life and labor. While not explicitly detailed in the context within the Progressive Era section, the preceding mention of “slum conditions” and the rise of “labor unions and socialist movements” points to the issues that reformers tackled. The Progressive movement sought to rein in corporate power, improve public health, and ensure fairer labor practices, signifying an evolving role for government in regulating the economy and safeguarding citizen welfare.

By laying the groundwork for greater social responsibility and governmental oversight, the Progressive Era demonstrated America’s capacity for systemic reform in the face of complex problems. This period set important precedents for how a developed nation could adapt its institutions to mitigate the negative impacts of technological and economic advancement, while also expanding rights. The lessons learned about balancing progress with social welfare, and the mechanisms established for reform, are vital components of the nation’s long-term resilience and its ability to orchestrate a ‘resurgence’ that is both economically robust and socially equitable.

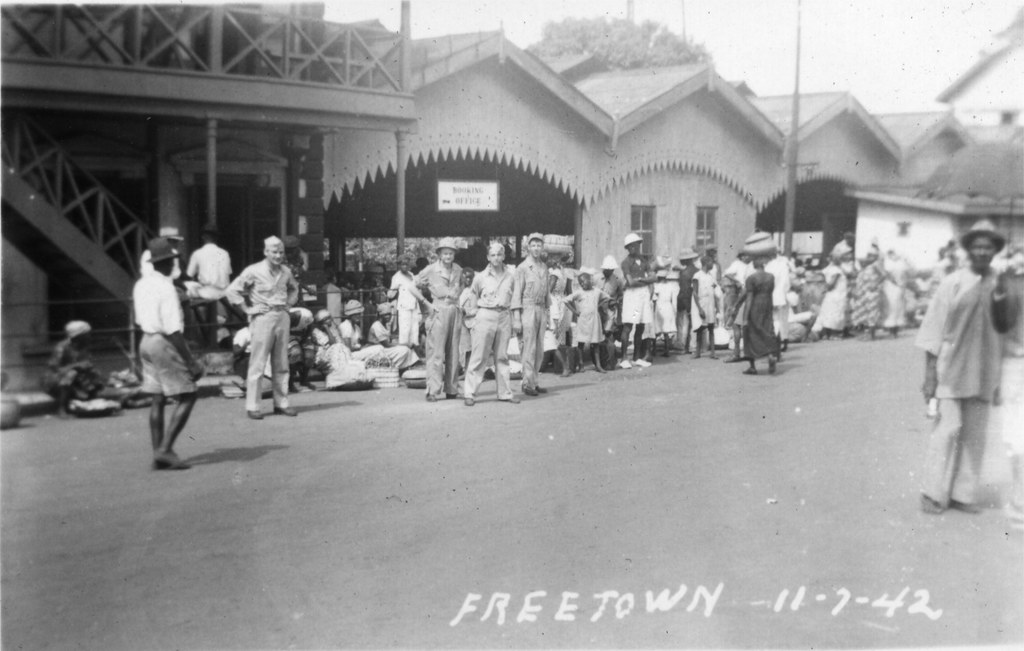

7. **World Wars and the Rise to Global Power: Forging Industrial Capacity Through Conflict**

The 20th century presented a crucible of global conflict that profoundly shaped America’s industrial might and its emergent role on the international stage. Initially, the United States maintained neutrality in World War I, but its entry in 1917, alongside the Allies, proved pivotal in helping to turn the tide against the Central Powers. This period required an immense mobilization of resources and production, demonstrating the nation’s inherent capacity for rapid industrial scaling in response to external demands.

Even more significantly, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 irrevocably drew the U.S. into World War II. The ensuing war effort necessitated an unprecedented transformation of American industry, converting civilian production into a vast arsenal of democracy. This era saw the rapid development of advanced technologies, perhaps most notably the creation and deployment of the first nuclear weapons in August 1945, which brought the devastating conflict to a swift end.

Emerging from World War II relatively unscathed, the United States found itself in an unparalleled position of global leadership. Its economic power had surged, bolstered by an intact and re-oriented industrial base, while its international political influence expanded dramatically. This period solidified America’s status as a formidable global power, possessing both the economic muscle and the technological prowess to project its will and shape the post-war world order. The lessons in rapid technological innovation and mass production learned during these conflicts would become a foundational blueprint for future industrial endeavors.

8. **The Cold War Era: Superpower Competition and Technological Acceleration**

With the cessation of World War II, the global landscape rapidly reconfigured into a bipolar world, positioning the United States and the Soviet Union as rival superpowers. This geopolitical tension swiftly escalated into the Cold War, an ideological and technological arms race that would define the latter half of the 20th century. The U.S. adopted a policy of containment, aiming to limit the USSR’s sphere of influence and often engaging in regime change against governments perceived as aligned with the Soviets.

This era of intense competition became a powerful accelerant for technological innovation across numerous sectors. The Space Race, in particular, galvanized American scientific and engineering efforts, culminating spectacularly with the first crewed Moon landing in 1969. Beyond the visible triumphs of space exploration, the hidden engines of military research and development pushed the boundaries of computing, materials science, and automation, laying critical groundwork for what would become advanced robotics.

The relentless pursuit of strategic advantage during the Cold War fostered an environment where substantial government funding flowed into research institutions and private industries. This sustained investment created a robust ecosystem for technological advancement, driving breakthroughs that, while initially serving defense objectives, would eventually permeate and revolutionize civilian manufacturing. It established a precedent for large-scale, coordinated innovation that is now ripe for application in a new era of industrial resurgence.

The pressure to outmaneuver a global adversary meant that efficiency, precision, and the ability to operate in challenging environments became paramount in technological design. These very characteristics are central to the effectiveness of modern industrial robots. Thus, the shadow of Cold War competition inadvertently provided a long-term benefit, forging a national capacity for high-tech development that continues to yield dividends in contemporary manufacturing.

Read more about: The United States: A Comprehensive Historical, Geographical, and Governmental Overview

9. **Social Revolutions and Evolving Workforce Dynamics: Reshaping the Human Element of Industry**

The post-World War II period was not only a time of geopolitical tension but also one of profound domestic transformation within the United States. The nation experienced significant economic growth, coupled with widespread urbanization and a remarkable boom in its population. These demographic shifts fundamentally altered the composition and location of the American workforce, creating both new opportunities and novel challenges for industry.

Crucially, this era witnessed the powerful emergence of the civil rights movement, with figures like Martin Luther King Jr. leading the charge for equality in the early 1960s. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society” plan responded with groundbreaking laws, policies, and a constitutional amendment aimed at counteracting “some of the worst effects of lingering institutional racism.” These reforms began to dismantle systemic barriers, expanding access to education and employment for previously marginalized communities.

Simultaneously, the counterculture movement brought significant social changes, including a liberalization of attitudes towards recreational drug use and uality. This period also saw widespread opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam, which contributed to the end of military conscription in 1973. Such shifts reflected a questioning of traditional authority and a re-evaluation of societal values, impacting everything from labor relations to consumer preferences.

Perhaps one of the most significant shifts for the future of manufacturing was the dramatic increase in female paid labor participation during the 1970s. By 1985, “the majority of American women aged 16 and older were employed,” fundamentally altering workforce demographics and capacity. These social revolutions, while not directly technological, reshaped the available labor pool, diversified perspectives, and underscored the importance of an adaptable and inclusive workforce for any national economic strategy, including a robotics-powered manufacturing resurgence.

10. **The Digital Age and Global Economic Leadership: The Dawn of a New Technological Frontier**

The 1990s ushered in an era of unprecedented prosperity and technological acceleration in the United States, marked by the longest recorded economic expansion in American history. This period was characterized by a dramatic decline in U.S. crime rates and a relentless march of innovation that laid the digital foundation for the 21st century’s technological landscape. It was a time when information technology began to profoundly redefine economic activity.

Groundbreaking technological innovations proliferated across various sectors. The World Wide Web, the continuous evolution of the Pentium microprocessor in accordance with Moore’s law, and the development of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries transformed communication and portable power. Furthermore, the first gene therapy trial and early advancements in cloning emerged or were significantly improved upon in the U.S., signaling leadership in biotechnological frontiers.

The formal launch of the Human Genome Project in 1990 exemplified America’s commitment to large-scale scientific endeavors, while Nasdaq becoming “the first stock market in the United States to trade online in 1998” underscored the rapid digitization of financial markets. These developments collectively fostered an environment where complex data processing, rapid information exchange, and sophisticated automation became commonplace, moving beyond theoretical concepts into practical applications.

This digital revolution, with its inherent focus on precision, interconnectedness, and automated processes, directly prefigured the capabilities required for advanced robotics and smart manufacturing systems. The infrastructure, talent pool, and innovative mindset cultivated during this era provided the essential fertile ground for the subsequent growth of automation and artificial intelligence, positioning America uniquely for a manufacturing resurgence powered by intelligent machines.

11. **Navigating Contemporary Challenges: Economic Recalibration and Political Tensions**

Despite periods of impressive growth, the trajectory of American power has not been without significant turbulence and introspection in the modern era. The U.S. housing bubble, which swelled through the early 2000s, culminated in 2007 with the onset of the Great Recession. This economic contraction, the “largest economic contraction since the Great Depression,” sent shockwaves through the global financial system and necessitated a difficult period of recalibration and recovery for the nation.

Beyond economic volatility, the 2010s and early 2020s have been marked by “increased political polarization and democratic backsliding” within the United States. This heightened internal division has manifested in various ways, creating an environment of uncertainty that can impact long-term strategic planning and societal cohesion. Such political friction can undeniably influence investment climates and the public-private partnerships crucial for industrial revitalization.

The country’s polarization reached a violent peak with “the January 2021 Capitol attack,” where “a mob of insurrectionists” entered the U.S. Capitol. This unprecedented event sought to prevent “the peaceful transfer of power” in an “attempted self-coup d’état,” starkly highlighting the fragility of democratic norms under extreme pressure. Such internal challenges demand critical examination, for a stable political and social environment is a prerequisite for sustained economic and technological advancement.

For America’s manufacturing resurgence to truly flourish, these contemporary challenges must be acknowledged and navigated effectively. While technological innovation can power production, the underlying societal and political infrastructure must be robust enough to support it. Addressing wealth inequality, fostering greater national unity, and reaffirming democratic institutions are not merely social goals but strategic imperatives for ensuring the long-term viability and equitability of a robot-powered industrial future.

Read more about: Silver’s Ascent: Could the ‘Poor Man’s Gold’ Redefine Investment Portfolios Amidst Economic Shifts?

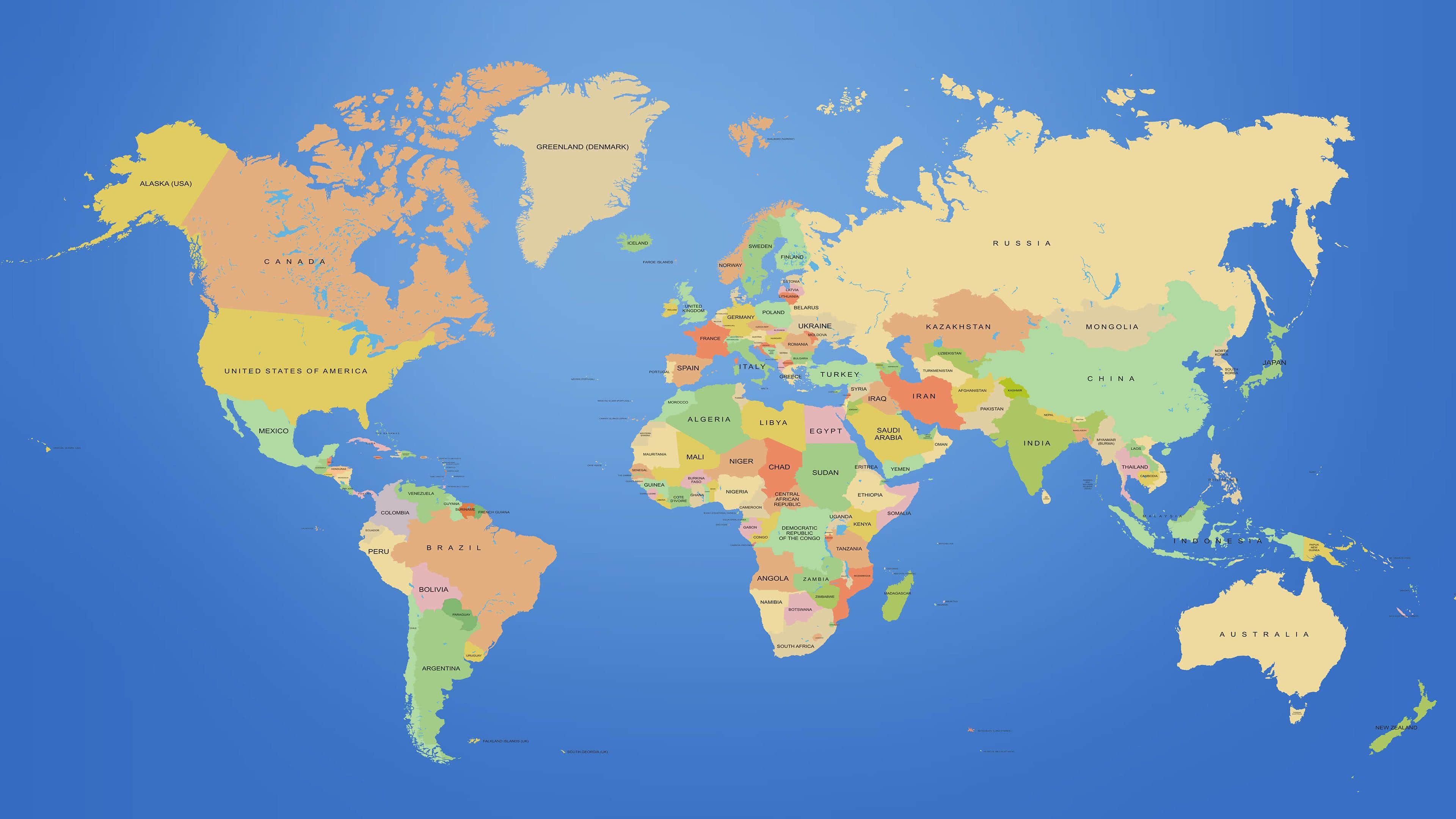

12. **America’s Enduring Geographic and Environmental Assets: The Foundation for Sustainable Innovation**

America’s physical landscape and its rich environmental heritage remain a fundamental, often understated, asset in its potential for future manufacturing resurgence. As “the world’s third-largest country by total area,” the United States boasts an unparalleled diversity of natural resources and geographical features. From the fertile plains of the Great Plains to the mineral wealth of the Rocky Mountains, the nation possesses a vast raw material base crucial for any industrial expansion.

The country’s “megadiverse” status is not just an ecological fact but an economic advantage. It is home to “about 17,000 species of vascular plants” in the contiguous states and Alaska, alongside “over 1,800 species of flowering plants” in Hawaii, and an astonishing array of mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, and insect species. This biodiversity, alongside varied climate types ranging from humid continental to tropical, provides diverse conditions for agricultural and bio-industrial innovation, supporting specialized manufacturing needs.

Furthermore, a significant portion of the country’s land, “about 28%,” is publicly owned and federally managed, primarily in the Western States. This expansive network of “63 national parks” and hundreds of other protected areas, administered by agencies like the National Park Service, represents a commitment to conservation. Such public lands offer opportunities for sustainable resource management and provide settings for outdoor recreation and scientific research, fostering a connection to the natural world.

However, the “Wired” perspective necessitates a critical look at the environmental issues confronting the nation. Debates on “non-renewable resources and nuclear energy, air and water pollution, biodiversity, logging and deforestation, and climate change” highlight significant challenges. Extreme weather incidents, increasing frequency of heat waves, and persistent droughts demand innovative, sustainable solutions from future manufacturing. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and legislation like the Wilderness Act and the Endangered Species Act offer frameworks for addressing these, emphasizing that a truly resilient manufacturing resurgence must integrate environmental stewardship with technological progress, ensuring long-term sustainability and resource security.

From the foundational tenets of liberty and self-governance, through the crucible of continental expansion and civil strife, and across the dramatic surges of industrialization and technological revolution, America’s narrative is a testament to persistent adaptation. The nation’s inherent dynamism, coupled with its unparalleled geographic diversity and a history of overcoming profound challenges, points toward a future where a new wave of innovation can reshape its industrial core. As we look ahead, the strategic integration of advanced robotics, driven by the ingenuity and resilience forged over centuries, stands poised to power not just a resurgence in manufacturing, but a renewed assertion of American leadership on the global technological frontier.