Music, in its profound capacity to stir emotion and shape perception, has long been an indispensable, if often subliminal, architect of the cinematic experience. From the earliest flickering images on a screen to today’s blockbuster spectacles, the aural landscape a film inhabits is as vital as its visual narrative, a truth keenly observed by scholars such as James Knippling of the University of Cincinnati. His research, presented to the College English Association, highlights the transformative power of scores and soundtracks, illustrating their critical role as a formal component that can, indeed, “make or break a movie.” The journey of film music, as Knippling and other historians reveal, is one of continuous evolution, adaptation, and artistic innovation, deeply intertwined with the development of the medium itself.

Indeed, the history of the film score is as varied and rich as the history of film itself, a complex tapestry woven from pragmatic necessity, artistic aspiration, and technological advancement. It is a chronicle that commences with live pianists accompanying the Lumière brothers’ initial screenings and extends to the sophisticated, often genre-bending, orchestral and electronic compositions of the present day. This enduring presence and remarkable adaptability raise a compelling question: what is it about these classic scores that not only allows them to persist but also prompts their reinterpretation, re-performance, and even re-recording by new generations of artists and ensembles? The answer lies in their inherent artistic merit, their foundational role in cinematic language, and their capacity to transcend their original contexts, taking on lives of their own.

We embark on an in-depth exploration of the artistic and technical elements that define these pivotal works, uncovering the reasons why their melodies continue to echo through concert halls and recording studios, finding fresh voices and renewed appreciation. This article will delve into the historical milestones, the influential composers, and the intricate processes that have cemented these scores as timeless masterpieces, illuminating their ongoing relevance and the continuous impulse to engage with them anew, whether through scholarly analysis, live performance, or contemporary re-recording efforts.

1. **The Foundational Role of Music: From Silent Screens to Synchronized Sound**Before the advent of synchronized sound, music’s presence in cinema was born from a dual necessity: to mask the mechanical din of early projectors and to enrich the viewing experience. As early as 1895, the Lumière brothers’ first screenings featured a hired pianist, acknowledging music’s immediate capacity to elevate the crude novelty of moving images into a more immersive, engaging event. This instinctual recourse to agreeable sound to neutralize disagreeable noise laid the groundwork for an art form that would profoundly shape cinematic perception, proving that music was not merely an embellishment but an integral component from cinema’s very inception.

The silent films of the early twentieth century, paradoxically, relied heavily on powerful cinematic scores to convey emotion, advance narrative, and immerse audiences. The Soviet epic *Battleship Potemkin*, for instance, originally featured a score by Edmund Meisel, a work so foundational that it “has since been rescored multiple times,” underscoring the enduring significance and interpretive malleability of such early compositions. These scores were often live accompaniments, ranging from solo pianists and organists to full orchestras, guided by cue sheets that meticulously outlined musical moods and transitions, transforming fleeting images into dramatic spectacles through the power of sound.

This era also saw pioneering efforts to provide full-length, original scores for films, such as Louis F. Gottschalk’s compositions for The Oz Film Manufacturing Company in 1914, and Camille Saint-Saëns’ music for *The Assassination of the Duke of Guise* in 1908. These early, ambitious attempts to integrate music more formally into the cinematic fabric paved the way for the eventual breakthrough of the ‘talkie.’ *The Jazz Singer*, marking the transition to synchronized sound, offered an “exciting combination of original soundtrack, dialogue, and classic vaudeville songs,” becoming a monumental success and irrevocably altering the relationship between film and its accompanying score, ushering in an era where music became intrinsically tied to the filmic narrative.

2. **The ‘Unheard’ Music of Classic Hollywood: Orchestral Dominance and Subliminal Cues**In the “classic Hollywood period,” spanning the 1930s to the 1950s, the film score underwent a significant formalization. This era was characterized by the omnipresence of orchestral music, a direct consequence of the studio system’s operational model. As James Knippling observes, “The movie studios would keep full orchestras in constant employment, because they had to score every film they made, and they churned them out much quicker than today.” This industrial-scale production of cinema ensured that nearly every film, regardless of its genre or setting, was meticulously accompanied by a rich orchestral tapestry, solidifying a distinctive musical idiom for the burgeoning art form.

What defined this period’s scoring was its universal application and its intended effect. Knippling notes that a full orchestral score was employed “regardless of the film setting.” This meant that “Even if the film might be set out in the country with bullfrogs, you’d still have the orchestral score — you wouldn’t have harmonicas and banjos. It was universal.” The primary objective of this music was not to draw attention to itself but to function as a “subliminal emotional cue — something the audience isn’t necessarily aware of,” guiding viewers’ feelings without explicitly intruding upon their consciousness. This approach established a powerful, yet often invisible, emotional undercurrent for cinematic storytelling.

This philosophy of “unheard” music directly paralleled the dominant visual aesthetic of the time, often described as the “invisible style.” Knippling explains, “The camera’s not drawing attention to itself. It’s gliding around seamlessly, showing you what it hopes you will take as the unmediated ‘real.’” Just as the cinematography aimed for an illusion of objective reality, the score sought to create an immersive emotional environment without foregrounding its own artistry. This seamless integration of music and image became a hallmark of classic Hollywood, creating a powerful, yet discreet, enhancement of the narrative, a subtlety whose enduring effectiveness continues to be studied and appreciated today, often leading to re-examination and new performances of these foundational scores.

3. **The Golden Age of Orchestral Scores: Maurice Jarre, Epic Cinema, and Themes with a Life of Their Own**

The 1950s and 1960s are often celebrated as the “high watermark of the orchestral film score,” an era when film music reached new heights of grandeur and emotional depth. This period was epitomized by the epic films of David Lean, which were invariably “accompanied by similarly epic scores by Maurice Jarre.” Jarre’s work transcended mere accompaniment, becoming an intrinsic part of the cinematic event, defining the scale and emotional resonance of masterpieces that continue to captivate audiences worldwide. His scores during this time elevated the art of film music to an unprecedented level of public recognition and critical acclaim.

Jarre’s compositions for films such as *Doctor Zhivago* and *Lawrence of Arabia* were “epic in scale,” perfectly mirroring the vast landscapes and sweeping narratives they underscored. What made these scores truly remarkable was how the “score itself took on a life of its own, outside the picture itself.” A prime example of this phenomenon is ‘Lara’s Theme’ from *Doctor Zhivago*, which was famously “re-released as the pop single ‘Somewhere, my love’ by Connie Francis,” achieving immense popularity. This transformation allowed the music to reach “a different audience, stripped from its filmic context but consequently more accessible,” demonstrating the intrinsic power and appeal of these compositions beyond their original cinematic setting.

Maurice Jarre’s impact was profound; he is rightly remembered as “one of the most influential film composers of all time,” a testament to the enduring power of his grand and sweeping themes. He earned three Oscars for his collaborations with Lean, solidifying his status as a master of the orchestral form. The ability of such themes to resonate independently of their original films speaks to their inherent musical strength and universal emotional appeal. It is this capacity for timelessness and widespread recognition that naturally encourages future generations to revisit, perform, and re-record these classic scores, ensuring their legacy endures in various forms and contexts.

4. **Classical Infusion and Modernist Shifts: Stanley Kubrick’s Innovative Use and the Rise of Jazz and Atonality**

The landscape of film scoring underwent significant shifts in the 1960s, notably with the controversial yet visionary practice of replacing original film scores with classical music. Stanley Kubrick’s *2001: A Space Odyssey* stands as the most pertinent example, where Kubrick, opting for existing recordings of classical works, discarded original scores by Alex North and Frank Cordell. His decision to integrate pieces by György Ligeti, alongside more traditional choices like Johann Strauss, revolutionized how pre-existing music could shape a film’s artistic identity, demonstrating a profound trust in the inherent power and resonance of established compositions.

Kubrick’s selections created truly “iconic moments in filmmaking.” The ethereal grace of Johann Strauss’s *Blue Danube* Waltz accompanying the space-station docking scene, and the majestic ‘sunrise’ from Richard Strauss’s *Also Sprach Zarathustra*, became instantly recognizable, elevating these classical pieces to new popular consciousness. This ingenious use not only defined the film’s unique aesthetic but also “made them increasingly popular in the classical canon,” blurring the lines between cinematic and concert hall appreciation and inspiring a new engagement with these enduring works that could certainly extend to contemporary re-recordings for fresh interpretations.

Beyond the classical infusion, the 1950s also witnessed the “rise of the modernist film score,” characterized by a bold willingness to experiment with jazz influences and dissonant scoring. Directors like Elia Kazan embraced this, working with Alex North, whose score for *A Streetcar Named Desire* (1951) “combined dissonance with elements of blues and jazz.” Leonard Bernstein’s score for *On the Waterfront* (1954) echoed “earlier works by Aaron Copland and Igor Stravinsky with its ‘jazz-based harmonies and exciting additive rhythms.'” Leonard Rosenman ventured into atonality for *East of Eden* and *Rebel Without a Cause* (1955), inspired by Arnold Schoenberg, while Bernard Herrmann famously experimented in *Vertigo* (1958) and *Psycho* (1960). The use of non-diegetic jazz, notably Duke Ellington’s score for *Anatomy of a Murder* (1959), further underscored this innovative spirit, pushing the boundaries of what film music could be and establishing a rich tradition for future composers to draw upon and for new ensembles to reinterpret.

5. **The Maestros of Melody: John Williams, Iconic Thematic Scores, and Their Cultural Bleed**In the realm of contemporary orchestral film scoring, John Williams stands as arguably the most “pertinent example of a recent film composer who uses the orchestra to excellent effect.” His work is universally “defined by ear-catching themes,” establishing scores that are “among the most recognisable in the cinematic repertoire.” Williams possesses a singular ability to craft melodies and motifs that instantly embed themselves in the collective consciousness, forging an emotional connection with audiences that few other composers have achieved. His compositions are not merely background music; they are characters in their own right, vital to the narratives they inhabit.

Williams’s extensive oeuvre encompasses some of cinema’s most beloved and commercially successful franchises, including the iconic *Star Wars* and *Indiana Jones* series. Beyond these epic adventures, his trophy cabinet gleams with Oscar wins for emotionally resonant scores such as *E.T.*, *Schindler’s List*, and *Jaws*. Of these, the theme to *Jaws* is arguably the “most iconic.” The simple yet terrifying “repeated motif of the two deep notes, which some scholars have argued echo the shark’s heartbeat,” masterfully builds tension, speeding up and crescendoing “to high pitched terror.” This theme, often used with POV shots of the unseen predator, has “bled into popular culture” and is rightly considered “an icon of movie music,” demonstrating music’s power to transcend the screen.

The profound impact of Williams’s work extends far beyond the cinema, influencing not only subsequent film composers but also gaining increasing recognition within the classical music world. The Norwegian contemporary classical composer Marcus Paus, for instance, has lauded Williams as “one of the great composers of any century,” praising his ability to integrate “dissonance and avant-garde techniques within a larger tonal framework.” Paus suggests that Williams “might also have come the closest of any composer to realizing the old Schoenbergian utopia that children of the future would be whistling 12-tone rows.” This high regard underscores why Williams’s classic scores are not just remembered but continuously performed by major orchestras and pops orchestras, signaling an ongoing appreciation that often translates into fresh recordings and re-interpretations, ensuring their vibrancy for generations to come.

6. **Beyond the Orchestra: Genre Blending and Global Influences in Film Composition**While orchestral scores form the bedrock of film music, the art form has always shown a remarkable capacity for integration, drawing from a vast palette of musical genres and cultural traditions. Beyond the classical realm, jazz has frequently been employed to evoke specific moods and settings, adding a layer of sophisticated grit or sultry allure. Bernard Herrmann’s score for *Taxi Driver*, completed just two days before his death, is a masterful example, juxtaposing “dissonant notes in the violins with a smooth saxophone solo to describe the sleaze of 70’s New York.” Other notable examples include Miles Davis’s minimalist, atmospheric score for *Elevator to the Gallows* and Krzysztof Komeda’s unsettling soundtrack for Roman Polanski’s debut film, *Knife in the Water*, showcasing jazz’s versatility in defining cinematic atmosphere.

Modern film scores have also embraced popular music, sometimes integrating existing tracks to represent an era or character, or having composers orchestrate original compositions that complement popular songs. Films like *Guardians of the Galaxy* and *Back to the Future* famously utilize popular music to define their worlds. Alan Silvestri, for instance, at times orchestrates compositions that are “accompanied by tracks such as ‘The Power of Love’ and ‘Back in Time,’ both by Huey Lewis and The News.” This judicious blend creates a unique “sense of lightness that deviates from the fanfare-like main theme,” forging an immediate connection with audiences through familiar sounds while also providing a rich, multi-layered sonic experience.

Perhaps most compelling is the way many scores “draw from worldly influence to create sound that cements itself into popular culture.” Ennio Morricone’s iconic score for *The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly* is a prime illustration of this global fusion. In this groundbreaking work, Morricone ingeniously uses “a culmination of post-tonal music theory, Celtic song, gregorian chant, and mariachi trumpets to create the sound of the spaghetti western,” a sonic identity now inextricably “associated with the wild west.” This audacious genre-blending demonstrates film music’s boundless potential for innovation and its ability to forge entirely new cultural sounds, making these diverse and influential scores ripe for continuous re-evaluation, scholarly study, and new recordings that explore their complex origins and enduring appeal.

7. **The Collaborative Art: Film Composers and the Dialogue with the Classical Canon**The dialogue between film composers and the classical music canon is intricate, marked by both skepticism and growing recognition. Its journey towards high art acknowledgment has been a complex evolution. This discourse highlights why classic film scores warrant re-evaluation and re-recording, affirming their inherent artistic merit within the broader classical continuum.

History showcases notable crossover artists, blurring lines between concert hall and silver screen. Miklos Rozsa, a distinguished Czech classical composer, penned *Ben Hur*’s triumphant score. Leonard Bernstein, director of music at the New York Philharmonic, also composed for cinema. These collaborations underscore the profound creative demands in crafting cinematic music, often on par with concert hall compositions.

Today, the classical music establishment increasingly embraces film scores as legitimate high art. World-class orchestras regularly present film music concerts, attracting appreciative audiences. Marcus Paus lauds John Williams as “one of the great composers of any century,” praising his integration of “dissonance and avant-garde techniques within a larger tonal framework.” This critical acceptance roots film music within classical artistry, making re-recordings crucial for new interpretations.

8. **The Meticulous Craft: From ‘Spotting’ Cinematic Moments to Precise Musical Synchronization**The intricate journey of a film score, from concept to auditory reality, embodies meticulous craft and profound collaboration. A composer typically joins the creative process in the film’s later stages, presenting an unpolished “rough cut” to discuss desired musical style and emotional tone. This interaction sets the course for the sonic tapestry, crucial for defining the cinematic experience.

Central to “spotting,” director and composer meticulously review the film. They take precise timing notes for every music segment, detailing cue durations and alignment with on-screen dramatic events. This granular precision ensures the score functions as an organic narrative extension, enhancing every visual beat with unerring accuracy through advanced synchronization techniques like SMPTE timecode and “Free Timing.”

Occasionally, the creative dynamic shifts, with music influencing editing. Godfrey Reggio edited *Koyaanisqatsi* to Philip Glass’s compositions. Steven Spielberg granted John Williams complete artistic freedom for *E.T.*’s finale, re-editing the scene to match Williams’s music. These instances highlight the score’s powerful influence, even pre-empting the final visual cut and revealing varied approaches to film composition, sometimes based on script impressions alone.

9. **The Composer’s Canvas: Diverse Approaches and Influences in Writing a Score**With “spotting” complete, the composer faces the profound artistic challenge of writing the score. This stage is deeply personal, reflecting individual sensibilities and technical preferences. Some composers adhere to tradition, crafting notes by hand, while others embrace digital tools and sophisticated software to create intricate MIDI “mockups” for early director review.

The timeframe for this creative phase, typically around six weeks, demands prodigious talent and discipline. Dozens of minutes of original, emotionally resonant music must be produced under immense pressure. The score’s substance is profoundly shaped by a constellation of variables, including desired emotions, character nature, and evocative scenery, all acting as vital prompts.

Compelling examples demonstrate ingenious weaving of cultural or thematic elements. Howard Shore, in *The Lord of the Rings*, uses a tin flute to evoke The Shire’s Celtic, pastoral feeling, imbuing scenes with nostalgic reminiscence. Beyond purely orchestral elements, many scores deftly integrate popular music or draw from worldly influences. Ennio Morricone’s *The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly* fuses “post-tonal music theory, Celtic song, Gregorian chant, and mariachi trumpets,” forging the iconic “spaghetti western” sound. These audacious approaches underscore boundless creativity, crafting sounds that serve narrative and cement into popular culture.

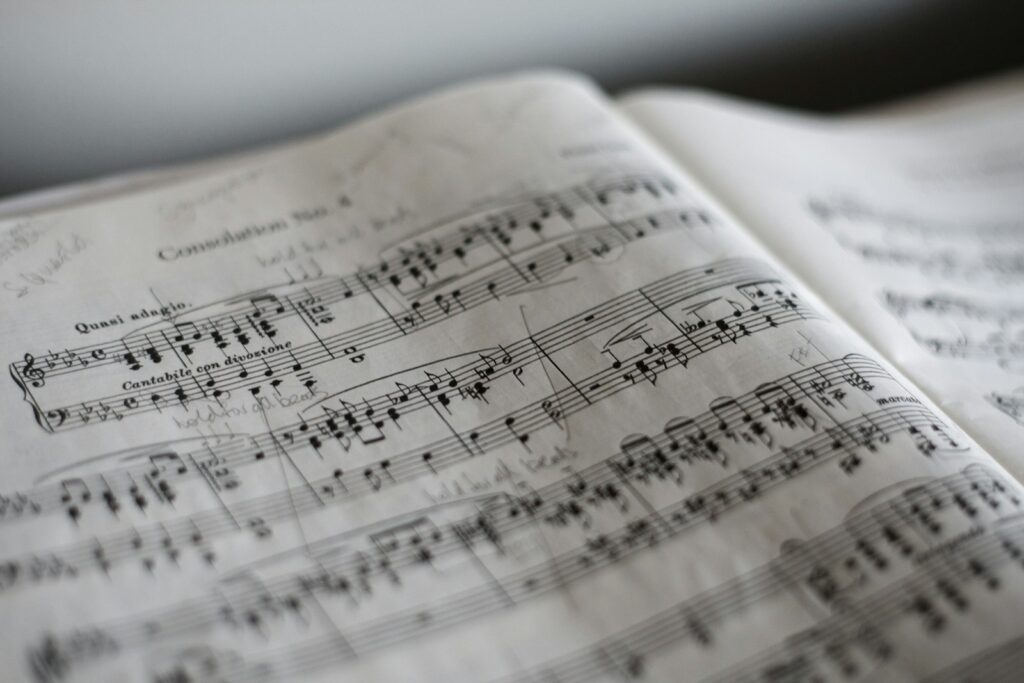

10. **Bringing the Score to Life: The Complex Stages of Orchestration and Recording**After composition, the musical blueprint undergoes meticulous preparation for live performance: orchestration and recording. Orchestration transforms melodies and harmonic ideas into instrument-specific sheet music, “fleshing out” the score to realize the composer’s vision. This critical step translates abstract concepts into performable parts, with orchestrator input varying from direct transcription to creative contribution. Tight post-production schedules often necessitate collaborative arrangements.

Once orchestrated, music copyists print the sheet music. The recording session is a highly specialized event, featuring an orchestra or ensemble performing the music, often conducted by the composer. Musicians, though often uncredited, are contracted professionals. Esteemed groups like the London Symphony Orchestra are regularly engaged, reinforcing film music’s classical lineage.

Precision is paramount during recording. The orchestra performs before a large screen displaying the film, ensuring perfect alignment. Conductor and musicians typically wear headphones, hearing a “click-track”—a series of clicks synchronized with meter and tempo changes. This indispensable guide ensures flawless timing, underscoring every emotional nuance and dramatic shift. This intricate dance makes re-recordings fascinating, offering new sonic possibilities or optimal fidelity.

Read more about: Quincy Jones, the Master Orchestrator Whose Boundless Influence Reshaped Global Music and Entertainment, Dies at 91

11. **Navigating Creative Challenges: The Enduring Influence and Controversies of ‘Temp Tracks’**The widespread use of “temp tracks”—temporary music during editing—serves as both a practical aid and a challenge for original composers. Directors employ these pieces to establish mood, character, or rhythmic pace, envisioning emotional impact before an original score exists. Though intended as editing tools, temp tracks frequently exert lasting influence, becoming a formidable creative hurdle.

A critical contention arises when directors, familiar with temporary music, implicitly or explicitly ask composers to imitate its style. This can restrict creative freedom, pushing towards emulation rather than innovation. Such directorial attachment can lead to a meticulously crafted original score being rejected in favor of the familiar temp music, illuminating its powerful psychological grip over a film’s creative vision.

Cinema history is rich with instances where original scores were discarded due to a director’s allegiance to a temp track. Notably, Stanley Kubrick’s *2001: A Space Odyssey* saw him choose existing classical recordings over commissioned scores from Alex North. This decision powerfully illustrates a director’s vision overriding bespoke compositions. These controversies reveal why film scores warrant re-recording for technical improvements and scholarly re-evaluation.

Read more about: Queen’s Enduring Reign: A Definitive Journey Through the Band’s Formative Years and Iconic Triumphs (1968-1986)

12. **The Thematic Heart: The Power of Leitmotifs in Character and Narrative Development**At the core of effective film scoring lies the ingenious application of recurring musical themes, rooted in Wagner’s leitmotif. These signatures—brief, evocative melodies—represent characters, events, ideas, or objects within a film’s narrative. Dynamically employed, they appear in various permutations depending on the on-screen situation, subtly interwoven to enrich storytelling and deepen emotional recall. Their power lies in forging instant, subconscious connections, transforming abstract visuals into tangible emotional experiences.

Leitmotifs are a cornerstone for genre enthusiasts and scholars, offering profound subtext and continuity. John Williams’s *Star Wars* scores exemplify this, featuring rich themes for characters like Darth Vader and Princess Leia. These motifs announce a character’s presence and evolve with their journey, signifying emotional state or narrative arc. *The Lord of the Rings* similarly uses an intricate web of recurring themes for characters, creatures, and locations, creating an immersive sonic universe.

Leitmotifs’ enduring impact extends to cinematic universes. Jerry Goldsmith’s powerful Klingon theme from *Star Trek: The Motion Picture* was so indelible that subsequent composers frequently quoted it. This continuity extended to television, where Goldsmith’s theme consistently identified Worf, reinforcing his heritage across different saga iterations. Such thematic recursion demonstrates film music’s capacity to create powerful, evolving mythologies, cementing its place in cultural memory and ensuring narrative integrity.

The continuous re-examination and re-recording of classic film scores transcends mere preservation. It is a vital act of re-engagement with these thematic hearts, allowing new generations to rediscover their intricate craftsmanship and timeless emotional power. These scores embody an art form that continues to evolve and resonate. Their perpetual artistic vitality promises past melodies will inspire fresh voices and renewed appreciation, securing their place in the grand continuum of musical expression.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/kirstie-alley-dies-20050615_09-b191dad23e0e443488d39ad92d37fd8c.jpg)