The British Isles, steeped in millennia of human history, hold secrets whispered by ancient stones and buried artifacts. For centuries, the echoes of its earliest inhabitants, particularly those from the transformative Iron Age, have tantalized scholars and ignited imaginations. This era, roughly spanning from 800 BC to the Roman invasion in AD 43, was a crucible of development, marked by fortified settlements, innovative iron tools, and the intricate weaving of complex social structures.

Understanding this period is not merely an academic exercise; it is a profound journey into the very linguistic and cultural bedrock of the region. The Iron Age in Britain was a time of significant development and transformation, laying foundations that would shape the future of its peoples and their tongues. For those who delve into the study of language, exploring this period offers a rich tapestry of historical and cultural contexts that can greatly enhance the understanding of the English language and its deep, ancient roots.

Central to this historical tapestry are the Insular Celts, the speakers of the Insular Celtic languages who populated the British Isles and Brittany. Their story is one that has been painstakingly pieced together through a fascinating interplay of archaeology, linguistics, and population genetics. By meticulously examining the remnants of their material culture, the subtle shifts in language, and the genetic markers carried through generations, researchers have begun to decode the intricate narrative of these ancient tribes, revealing not a ‘secret language’ in the clandestine sense, but rather the long-obscured patterns and structures of their tongues and the vibrant lives they lived.

1. **The Enigma of the Insular Celts**To truly grasp the linguistic landscape of the British Isles, one must first understand the peoples who shaped it: the Insular Celts. These were the speakers of the Insular Celtic languages who inhabited the British Isles and Brittany, their presence extending from the British–Irish Iron Age through Roman Britain and into Sub-Roman Britain, reaching up until the early Middle Ages. They comprised distinct groups such as the Celtic Britons, the Picts, and the Gaels, forming a complex mosaic of interconnected cultures.

Their influence was profound and widespread. The Insular Celtic languages themselves are believed to have spread throughout these islands during either the Bronze Age or the early Iron Age. This era saw the establishment of cultural and linguistic patterns that would resonate for centuries, influencing the very nomenclature of the land and the fundamental ways its inhabitants communicated. Their societal structures, religious practices, and material culture speak volumes about their sophisticated world.

These ancient communities adhered to an Ancient Celtic religion, overseen by a high-ranking professional class known as druids. This spiritual dimension underscores the depth of their cultural identity. Furthermore, some of the southern British tribes maintained robust connections with mainland Europe, particularly with Gaul and Belgica, a relationship evidenced by their practice of minting their own coins, reflecting a degree of economic and political sophistication.

By the 10th century, the Insular Celts had diversified significantly, branching into various Brittonic-speaking groups such as the Welsh in Wales, Cornish in Cornwall, Bretons in Brittany, and Cumbrians in the Old North. Concurrently, Goidelic-speaking populations emerged, including the Irish in Ireland, Scots in Scotland, and Manx on the Isle of Man, showcasing the rich tapestry of Celtic heritage that continued to evolve across the region.

2. **Tracing the Linguistic Roots: Brittonic and Goidelic Branches**The Insular Celtic languages are fundamentally divided into two major groups, forming the bedrock of linguistic study in the British Isles: Brittonic in the east and Goidelic in the west. This geographical distribution offers vital clues to their historical spread and subsequent diversification. While Continental Celtic languages are attested from as early as the sixth century BC, allowing for a confident reconstruction of Proto-Celtic, Insular Celtic languages only become firmly documented during the early first millennium AD.

One prominent theory, the “Insular Celtic hypothesis,” has gained favor among Celtic historical linguists since the latter part of the 20th century. This hypothesis posits a single wave of immigration of early Celts, associated with the Hallstatt D culture, to both Great Britain and Ireland. Following their arrival, these groups are believed to have soon divided into two isolated populations, one in Ireland and one in Great Britain, leading to the split of Insular Celtic into Goidelic and Brythonic around 500 BCE.

An alternative scenario suggests that the migration might have brought early Celts first to Britain, where a largely undifferentiated Insular Celtic was spoken. From Britain, Ireland was then colonized at a later stage. Linguistic analysis, particularly the absolute chronology of sound changes detailed in Kenneth Jackson’s ‘Language and History in Early Britain,’ points out that British and Goidelic remained essentially identical as late as the mid-1st century CE, apart from the P/Q isogloss. This intricate linguistic divergence provides critical insights into their evolutionary path.

The Goidelic branch embarked on a distinct developmental trajectory, evolving into Primitive Irish, then Old Irish, and subsequently Middle Irish. It was only with the historical, medieval expansion of the Gaels that this branch further diversified into the modern Gaelic languages: Modern Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Meanwhile, Common Brythonic followed its own complex path. It split into two branches, British and Pritenic, largely as a consequence of the Roman invasion of Britain in the 1st century.

By the 8th century, Pritenic had developed into Pictish, a language that would tragically become extinct during the 9th century. Concurrently, the British branch of Common Brythonic further split into Old Welsh and Old Cornish. These linguistic shifts were not merely academic distinctions; they were dynamic reflections of migrations, conquests, and cultural intermingling that continuously reshaped the linguistic map of the British Isles, leaving an indelible mark on its heritage.

3. **Archaeology’s Lens: Unpacking Celtic Settlement Theories**For decades, archaeologists and historians have grappled with understanding how Celtic culture and language arrived in the British Isles. Older theories often posited that the arrival of Celts, defined as speakers of Celtic languages derived from Proto-Celtic, roughly coincided with the beginning of the European Iron Age. A particularly influential model was T. F. O’Rahilly’s 1946 proposal of four separate waves of Celtic invaders into Ireland, spanning much of the Iron Age from 700 to 100 BCE.

However, the archaeological evidence for such distinct waves of invaders proved largely elusive, leading to a re-evaluation of these theories. Later research began to suggest a more gradual and continuous development of culture between the Celts and the indigenous populations. In Ireland, for instance, there was little archaeological support for large, intrusive groups of Celtic immigrants. This led archaeologists like Colin Renfrew to theorize that the native late Bronze Age inhabitants gradually absorbed European Celtic influences and language, rather than being displaced by mass invasions.

This “continuity model” gained further traction in the 1970s, popularized by Colin Burgess in his book *The Age of Stonehenge*. Burgess theorized that Celtic culture in Great Britain “emerged” from within, rather than being a direct result of invasion. He posited that the Celts were not invading aliens but rather the descendants of, or culturally influenced by, figures such as the Amesbury Archer, whose burial included clear continental connections, suggesting cultural diffusion rather than wholesale migration.

The archaeological record now shows substantial cultural continuity throughout the 1st millennium BCE, albeit with a significant overlay of selectively adopted elements of the “Celtic” La Tène culture from the 4th century BCE onwards. There are also claims of continental-style states appearing in southern England closer to the end of the period, possibly reflecting in part immigration by elites from various Gallic states, such as those of the Belgae. Evidence of chariot burials in England, beginning around 300 BC, is mostly confined to the Arras culture associated with the Parisii, offering tangible links to continental practices and potentially subtle movements of influential groups rather than overwhelming invasions.

4. **The Whispers of Pre-Celtic Tongues**While Celtic languages eventually dominated the British Isles, evidence suggests that earlier, pre-Celtic languages once held sway. The faint remnants of these ancient tongues may still be found in the names of certain geographical features that persist to this day. Rivers such as the Clyde, Tamar, and Thames are examples whose etymology remains unclear, leading scholars to speculate that their names might derive from a pre-Celtic substrate, a linguistic layer beneath the more commonly understood Celtic influences.

By approximately the 6th century BCE, it is widely thought that most of the inhabitants of the islands of Ireland and Britain were speaking Celtic languages. This period marks a significant linguistic shift, yet the lingering presence of pre-Celtic place names hints at the complex linguistic history of the region. These geographical markers serve as silent witnesses to earlier linguistic communities, whose speech patterns are largely lost to time but whose legacy endures in the very landscape itself.

A controversial phylogenetic linguistic analysis conducted in 2003 attempted to push back the age of Insular Celtic even further, suggesting its origins lay some 2,900 years before the present, a period slightly earlier than the conventional understanding of the European Iron Age. While such analyses are subject to ongoing debate, they underscore the profound antiquity of language in the British Isles and the intricate challenges involved in tracing its earliest forms. This constant re-evaluation of data, utilizing modern techniques, continues to refine our understanding of these ancient linguistic foundations.

Further theoretical constructs, such as the “Goidelic substrate hypothesis,” explore the possibility of a non-Celtic linguistic foundation upon which the Goidelic languages developed. Such hypotheses grapple with the complexities of language contact and assimilation, seeking to understand how new languages integrate with or supersede existing ones. The study of these pre-Celtic whispers provides a crucial, albeit challenging, dimension to our understanding of the linguistic evolution of the British Isles, highlighting the rich linguistic diversity that existed before the widespread adoption of Celtic tongues.

5. **Genetic Footprints: Unraveling Population Migrations**The story of language and culture in the British Isles is intricately intertwined with the movement of peoples, a narrative increasingly illuminated by population genetics. Migration, for example, has been shown to play a pivotal role in the spread of the Bell Beaker culture to the British Isles around 2500 BC. Genome-wide data from a vast array of ancient Europeans, including over 150 ancient British genomes, have been analyzed, revealing a dramatic genetic transformation. This research indicates that the introduction of Bell Beaker culture was accompanied by high levels of steppe-related ancestry, resulting in an astonishing replacement of about 90% of the local gene pool within just a few hundred years.

A 2003 study added another intriguing layer to this genetic narrative, showing that genetic markers associated with Gaelic names in Ireland and Scotland are also commonly found in parts of west Wales and England. These markers demonstrated similarities to the genetic profiles of the Basque people, while being markedly different from North Germanic populations. This finding initially supported suggestions of a large pre-Celtic genetic ancestry, potentially stretching back to the original Upper Paleolithic settlement, although this particular aspect was later debunked. Nevertheless, the study’s authors proposed that Celtic culture and language might have been imported to Britain at the beginning of the Iron Age through cultural contact, rather than through extensive “mass invasions,” aligning with certain archaeological theories.

In 2006, two popular books, *The Blood of the Isles* by Bryan Sykes and *The Origins of the British: a Genetic Detective Story* by Stephen Oppenheimer, further explored the genetic evidence for the prehistoric settlement of the British Isles. Their findings converged on the idea that while there is significant genetic evidence for a series of migrations from the Iberian Peninsula during the Mesolithic and, to a lesser extent, the Neolithic eras, there is comparatively little genetic trace of any major Iron Age migration. This suggested a dominant continuity of existing populations through the Iron Age, with cultural and linguistic changes perhaps driven by elite diffusion or smaller-scale movements.

More recent genetic studies have continued to refine this picture, finding evidence for some Late Iron Age migration of Celtic (La Tène) people to Britain and subsequently to north-east Ireland. A major archaeogenetics study in 2021 uncovered another crucial migration into southern Britain during the Bronze Age, specifically between 1300–800 BC. The newcomers in this event were genetically most similar to ancient individuals from Gaul, and their genetic marker swiftly spread through southern Britain during 1000–875 BC, though notably not northern Britain. The authors described this as a “plausible vector for the spread of early Celtic languages into Britain,” suggesting that Celtic arrived before the Iron Age, with Barry Cunliffe proposing that a branch of Celtic was already spoken in Britain, and this Bronze Age migration introduced the Brittonic branch, thus painting a dynamic and complex picture of linguistic and genetic interplay.

Read more about: Devon: An In-Depth Chronicle of England’s Southwestern Jewel, From Ancient Roots to Enduring Landscapes

6. **A Glimpse into Daily Life: Iron Age Villages**The Iron Age in Britain was not only a period of linguistic evolution but also a time when distinct community structures solidified. Villages of this era were typically small, self-sufficient communities, forming the backbone of tribal life. Their strategic placement was crucial; they were often situated on elevated ground, a deliberate choice made for defensive purposes, further reinforced by surrounding ditches and formidable ramparts, creating a protected enclave for their inhabitants.

The most recognizable architectural feature of these settlements was the roundhouse, the primary form of dwelling. These circular structures were ingeniously constructed with conical thatched roofs, supported by sturdy wooden posts, and walls crafted from wattle and daub. This practical design provided warmth and shelter, a testament to the resourcefulness and building skills of Iron Age peoples, shaping the domestic landscape of the era.

Survival within these communities revolved around a diverse array of activities. Agriculture was the unwavering mainstay, providing sustenance through the cultivation of essential crops such as barley, wheat, and oats. Alongside crop farming, villagers engaged in the rearing of livestock, including cattle, sheep, and pigs, which provided food, hides, and other vital resources. These combined agricultural efforts underpinned the self-sufficiency of the village economy.

These agricultural and pastoral pursuits necessitated a range of specialized tools and implements. Crucially, many of these were crafted from iron, marking a significant technological advancement from the preceding Bronze Age. The widespread adoption of iron, a more durable and versatile metal, revolutionized farming, warfare, and daily crafts, signifying a new era of material culture and efficiency for the Iron Age inhabitants of Britain.

Read more about: Seriously, Where Did They Go? 12 ‘Top’ Meanings and Terms That Shaped Our World (and Sometimes Vanished)

7. **Hierarchy and Harmony: Social Structures of Iron Age Britain**Within the fortified perimeters of Iron Age villages, a clear and intricate social structure governed daily life, characterized by a distinct hierarchy. Power and influence were primarily concentrated in the hands of an elite class, often referred to as chieftains or tribal leaders. These influential figures wielded considerable authority, acting as the primary decision-makers and protectors of their communities. Their status was paramount to the organization and security of the village.

These chieftains were not merely symbolic heads; they played active and multifaceted roles. They controlled vital resources, ensuring the distribution of food, land, and other necessities among their people. In times of conflict, they led their communities in warfare, commanding respect and loyalty. Furthermore, they served as crucial intermediaries between their people and the gods, performing rituals and interpreting divine will, thus holding significant spiritual as well as temporal power.

The common folk, forming the majority of the population, constituted the industrious engine of the village. They were engaged in a variety of essential occupations that sustained the community’s existence. These roles included farming the fields, weaving textiles for clothing and shelter, crafting pottery for storage and cooking, and blacksmithing, producing the iron tools and weapons that were so crucial to the era. Their collective efforts ensured the day-to-day functioning and prosperity of the settlement.

The division of labor within these communities was often clearly defined along gender lines. Men typically bore the primary responsibilities for farming and warfare, tasks demanding physical strength and communal defense. Women, on the other hand, took on essential domestic and craft-related responsibilities, such as weaving, cooking, and childcare. This complementary division ensured that all necessary functions for the community’s survival and growth were diligently managed, maintaining a functional harmony within the hierarchical structure of Iron Age Britain.

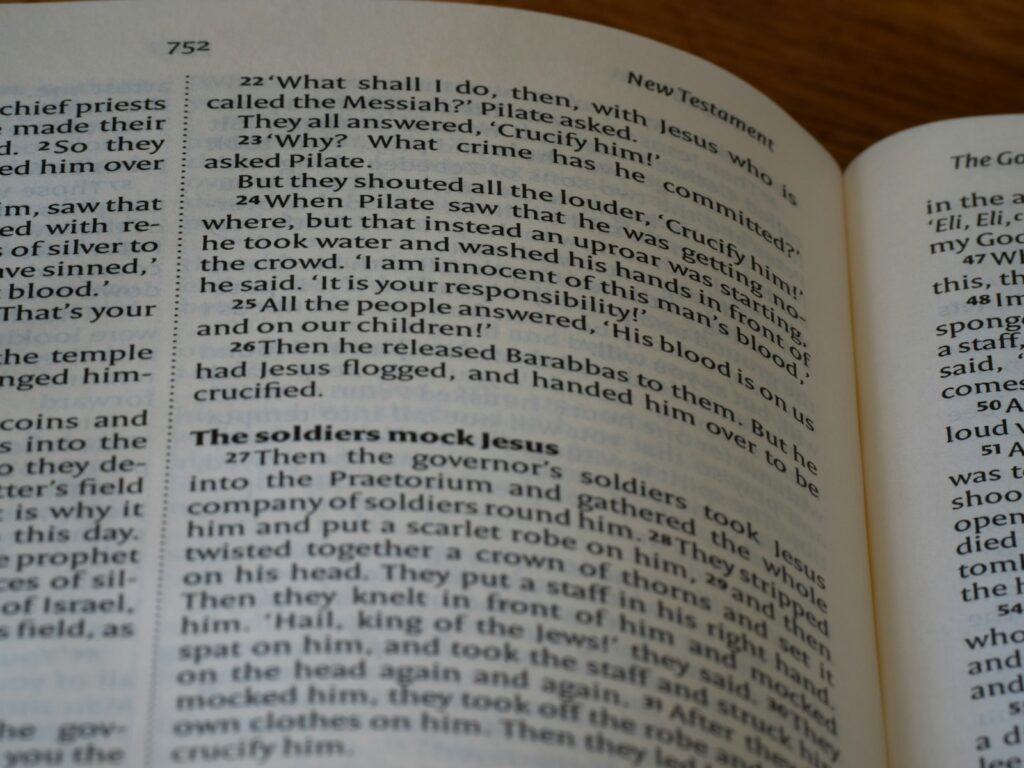

8. **The Roman Shadow: Lingua Franca and Enduring Resistance**The arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD marked a pivotal moment for the British Isles, forever altering its political, cultural, and to some extent, its linguistic landscape. As Roman legions swept across much of Britain, conquering territory and establishing their formidable infrastructure, they brought with them not only their laws and administration but also the ubiquitous Vulgar Latin, intended to be the lingua franca of their vast dominion. This period saw the emergence of a syncretized Romano-British culture, particularly flourishing in the southeastern regions, a blend of indigenous traditions and Roman influences.

Yet, unlike the extensive Romanization witnessed in Gaul, where the Gaulish language was almost entirely supplanted by Latin, Britain exhibited a remarkable linguistic resilience. While a British Latin dialect undoubtedly permeated the urban centers and administrative hubs of Roman Britain, it never achieved the pervasive influence necessary to wholly displace the indigenous British dialects spoken throughout the countryside. Pockets of Romance-speaking populations may have persisted as late as the 8th century, a testament to the limited, albeit significant, impact of Latin on the overall linguistic fabric.

Crucially, the Roman conquest was not absolute. Areas north of Hadrian’s Wall, a formidable defensive frontier, remained outside the direct control of the Empire. These territories, inhabited by peoples summarized under the term Caledonians, the ancestors of the later Picts, largely remained in a prehistoric state, shielded from Roman influence. Similarly, Ireland, with its Gaelic populations, also maintained its linguistic and cultural independence, existing beyond the reach of Roman legions. This geographical divide ensured the survival and continued evolution of Celtic languages in distinct, untrammeled pockets, setting the stage for their later trajectories.

While the Romans brought advancements and a new linguistic layer, the core Insular Celtic languages of Britain held firm, particularly in areas beyond direct Roman governance. The syncretic culture in the south was a fascinating blend, but the heart of British linguistic identity, though challenged, continued to beat. This enduring presence would prove crucial in the post-Roman era, shaping the linguistic future of the western parts of the island.

9. **Anglo-Saxon Tides: The Marginalization of British Tongues**The mid-5th century witnessed another seismic shift in the British Isles: the Anglo-Saxon invasion and settlement. As Roman power waned and eventually collapsed in Britain, Germanic peoples, primarily the Anglo-Saxons, migrated to the eastern and southern parts of the island, bringing with them their Western Germanic dialects, collectively known as Old English. This influx profoundly reshaped the demographic and linguistic map, setting in motion a long process that would gradually marginalize the indigenous British languages to the western fringes of the island.

The transition was not necessarily a straightforward mass immigration resulting in a complete replacement of the existing population. Instead, historical and linguistic evidence suggests a more nuanced process, potentially involving the arrival of a new elite who installed their culture and language as a dominant superstrate. This meant that while the existing populations might have largely remained, their language and culture were gradually overshadowed and eventually superseded by that of the newcomers. This dynamic also led to a fascinating period of British-Saxon syncretism during the 6th century, where rulers occasionally bore names reflecting both traditions, such as British rulers with Saxon names like Tewdrig, or Saxon rulers with British names like Cerdic, illustrating a complex period of cultural mingling.

As the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms solidified their control, the British languages found themselves increasingly confined to what is now Wales and Cornwall. This geographical retreat was a direct consequence of the eastward expansion of Old English. Concurrently, a similar linguistic transformation occurred in northern Britain, where the Gaels, speakers of Goidelic languages, established themselves over formerly Pictish-speaking populations, further diversifying the linguistic tapestry and contributing to the decline of Pritenic.

The displacement was gradual but relentless, pushing the ancient Celtic tongues into more isolated regions. This period underscores the immense power of conquest and cultural dominance in shaping linguistic destinies. The once widespread Brythonic languages, while not vanishing entirely, entered a new phase of existence, defined by their resilience in the face of a burgeoning new linguistic power, setting a challenging stage for their long-term survival.

10. **The Echoes in Place Names: An Enduring Celtic Toponymy**Even as new languages swept across the British Isles, the ancient Celtic tongues left an indelible mark upon the very landscape, a legacy most vividly preserved in its toponymy – the study of place names. Long after the sounds of Proto-Celtic and its Insular descendants receded from widespread use, the names given to rivers, mountains, and settlements continued to whisper their origins, providing invaluable linguistic archaeological insights for future generations. These names are not mere labels; they are historical artifacts, narrating stories of the earliest inhabitants and their profound connection to the land.

Many modern British place names proudly bear their Celtic heritage, serving as constant reminders of the linguistic substratum upon which later languages were built. For instance, the enduring presence of the prefix “Aber-” in names such as Aberdeen and Aberystwyth is a direct inheritance from the Celtic word signifying a “confluence of waters” or a “river mouth.” These locations, often situated at the joining of rivers or where a river meets the sea, reflect the ancient peoples’ keen observation of their natural environment and their practical, descriptive approach to naming significant geographical features.

Similarly, the suffix “-don,” which appears in prominent names like London and Swindon, traces its etymology back to the Celtic word for “hill” or “fort.” This denotes locations that were likely elevated settlements or fortified strongholds, strategically chosen for defense or vantage points. These linguistic markers allow us to reconstruct, in part, the ancient human geography of the British Isles, revealing patterns of settlement and the significance of topography to Iron Age communities.

While some river names like the Clyde, Tamar, and Thames are theorized to derive from an even older, pre-Celtic substrate, emphasizing the deeper linguistic layers of the islands, the widespread adoption and persistence of Celtic elements in countless other names underscore their dominant influence during the Iron Age. These geographical appellations are powerful cultural anchors, ensuring that the ancient languages, though diminished in spoken form, continue to resonate across the modern British landscape, connecting the present with a deep and vibrant past.

11. **Celtic Loanwords: Weaving Ancient Tongues into Modern English**Beyond the enduring geographical markers, the ancient Celtic languages have also enriched the English lexicon with a fascinating array of loanwords, acting as linguistic echoes of cultural exchange and historical interaction. While the Anglo-Saxon influence undoubtedly formed the primary grammatical and lexical bedrock of English, the continuous contact between Celtic and Germanic speakers, particularly in the centuries following the Anglo-Saxon migrations, led to a subtle yet significant borrowing of terms. These words, often tied to specific cultural roles, practices, or natural features, provide a tangible link to the Iron Age world and its unique expressions.

One of the most evocative examples is the English word “bard,” a term universally understood today to mean a poet or storyteller. Its direct lineage can be traced back to the Celtic word “bardos.” In ancient Celtic societies, bards held a revered position, acting not only as entertainers but also as keepers of oral history, genealogies, and legal knowledge. Their role was central to the cultural life of Iron Age communities, ensuring the transmission of traditions and narratives across generations. The adoption of this word into English reflects the profound cultural impact and recognition of this specific function, even by those who spoke a different tongue.

Another significant loanword is “druid,” which denotes a member of the high-ranking professional class in ancient Celtic cultures, often serving as priests, judges, teachers, and healers. This word finds its roots in the Celtic “druides.” The spiritual and intellectual authority of the druids was immense, underscoring their societal importance. The English assimilation of “druid” speaks volumes about the historical awareness and cultural interaction between the Celtic inhabitants and subsequent linguistic groups, highlighting a shared understanding, if not always acceptance, of these powerful figures.

While the number of direct Celtic loanwords into Old English might not have been as extensive as those from Latin or Norse, their presence is particularly meaningful. They are not merely vocabulary additions; they are cultural artifacts, preserving glimpses into the social structures, spiritual beliefs, and everyday lives of the Insular Celts. These linguistic borrowings demonstrate that despite periods of conflict and displacement, there was an ongoing, albeit often subtle, process of cultural and linguistic intermingling, leaving permanent imprints on the very language we speak today.

12. **The Enduring Power of the Spoken Word: Oral Traditions and Their Legacy**In Iron Age Britain, where written records were scarce and not uniformly utilized across all tribes, the spoken word held immeasurable power and was the primary conduit for the transmission of knowledge, history, and cultural identity. Oral traditions were not merely a means of communication; they were the very bedrock of societal memory, communal learning, and artistic expression. Bards, storytellers, and druids played pivotal roles in this vibrant oral culture, acting as living libraries and ensuring the continuity of tribal lore, epic tales, and spiritual teachings from one generation to the next.

These ancient storytellers, often endowed with prodigious memories and exceptional rhetorical skills, were the custodians of their people’s past. They recounted myths of creation, the brave deeds of ancestors, and the complex genealogies that cemented social ties and legitimacies. Through intricate poetic forms, rhythmic narratives, and often accompanied by musical instruments, they brought history to life, transforming dry facts into compelling and memorable performances that educated, entertained, and instilled a sense of collective identity among the Iron Age communities. Their performances were vital social events, reinforcing cultural values and community cohesion.

The legacy of these rich oral traditions did not simply vanish with the advent of written language or the shifting linguistic landscape. Instead, it subtly seeped into the emerging cultures and languages, influencing the narrative structures, thematic elements, and imaginative worlds that would later find expression in medieval literature and beyond. Even in modern British folklore, mythology, and regional storytelling, echoes of these ancient Celtic narratives can still be discerned, demonstrating a deep-seated continuity in imaginative thought and cultural expression.

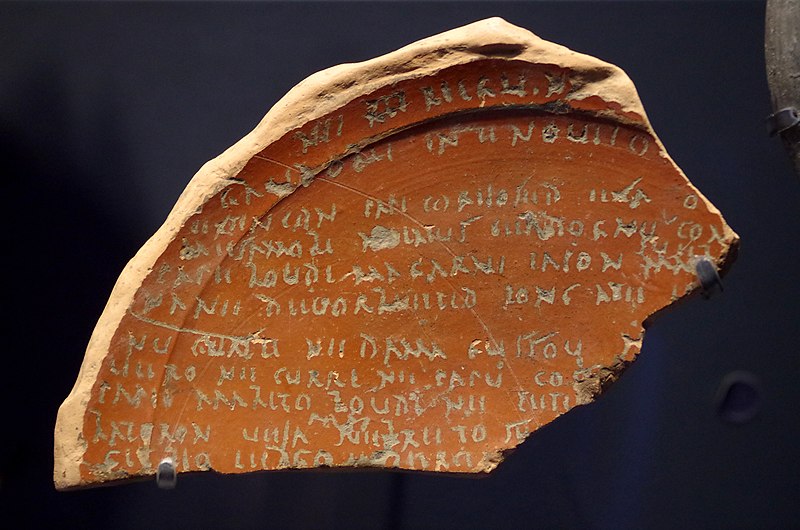

For those studying the linguistic and cultural heritage of the British Isles, understanding the profound impact of this oral past is crucial. It reminds us that language is more than just grammar and vocabulary; it is a living, breathing entity, deeply intertwined with the human experience of sharing stories, preserving collective memories, and shaping identity. The enduring presence of these oral legacies highlights the strength and resilience of Celtic culture, proving that the spoken word can indeed be as potent and long-lasting as any written inscription.