In our ceaseless pursuit of well-being, we often dedicate considerable attention to physical fitness, dietary choices, and emotional resilience. Yet, the nuanced intricacies of brain health, particularly as we navigate the passage of time, can sometimes escape the spotlight. Cognitive neuroscientists, who delve deep into the mechanics of the mind, consistently emphasize that maintaining peak brain function isn’t about fleeting fads or miracle supplements, but rather a holistic commitment to lifestyle modifications and behavioral adjustments that foster long-term cognitive vitality.

Dr. Antonio Puente, a board-certified clinical neuropsychologist and chief psychologist at George Washington University, succinctly captures this philosophy, stating, “It’s more of a lifestyle modification or set of behavior changes that over time can be helpful.” This perspective underscores that our daily habits, both overt physical actions and subtle mental exercises, collectively sculpt the landscape of our cognitive future.

This article will illuminate fourteen critical areas, combining direct advice from brain experts on memory-diminishing habits with a deeper dive into common linguistic confusions that demand a sharp and precise mind to navigate. By understanding and actively addressing these pitfalls, we can bolster our cognitive defenses, manage stress more effectively, and keep our minds exceptionally keen, ensuring that our memory and overall mental sharpness remain resilient for years to come.

1. **Avoid prolonged sitting.**

The sedentary lifestyle is a pervasive, yet often underestimated, threat to cognitive health. Brain experts advocate for regular physical activity, recognizing its capacity to provide an immediate surge in mental clarity and guard against dementia. Prolonged sitting is a habit many neurologists consciously avoid due to its detrimental effects.

Dr. Puente, for example, cycles ten miles to and from work daily. He emphasizes that disrupting extensive periods of inactivity is key; even brief interventions like standing or light movement every hour accumulate meaningful benefits for physical well-being and cognitive functions. Consistent efforts mitigate risks from extended stillness.

Research indicates that even short bursts of brisk exercise can substantially lower dementia risk. Dr. Puente paces hallways; Dr. Luis Compres Brugal strolls outside during breaks, gaining fresh air and sunlight, enhancing focus and reducing stress. Converting pockets of free time into movement opportunities fortifies both immediate and long-term brain health.

Read more about: Selecting the Right Ergonomic Chair for Remote Work: A Comprehensive Guide for Individuals Over 60

2. **Manage day-to-day stress effectively.**

Life presents inevitable stressors, yet sustained cognitive sharpness often hinges on one’s approach to these pressures. Neurologists emphasize maintaining emotional equilibrium, particularly by refraining from becoming unduly “riled up” by minor inconveniences.

The implication is clear: excessive or poorly managed emotional responses, especially to trivial issues, contribute to cognitive strain. Chronic stress releases hormones that negatively impact brain areas vital for memory and learning. Cultivating a measured reaction to life’s smaller challenges is a strategic practice for safeguarding mental well-being.

Choosing not to escalate minor annoyances into significant emotional turmoil conserves cognitive resources, maintaining a stable internal environment conducive to optimal brain function. Learning to let go of trivial irritations supports clearer thinking, better decision-making, and robust memory retention, a critical component of sustained cognitive sharpness.

Read more about: The 12 Strategic Time-Wasting Activities That Top CEOs Religiously Avoid for Peak Performance and Growth

3. **Distinguish ‘worse’ from ‘worst’.**

Beyond lifestyle, cognitive sharpness is reflected in navigating linguistic complexities with precision. “Worse” and “worst” represent a common, yet subtle, cognitive trap in English grammar. Despite similar sounds, these terms signify distinct degrees of negativity, and incorrect interchange impacts communication and clear thinking.

Confusion stems from their shared origin as forms of “bad.” Their roles differ: “Worse is what’s called the comparative form, basically meaning “more bad.” Worst is the superlative form, basically meaning “most bad.”” Mastering this distinction requires recall and application of specific rules, engaging cognitive processes related to language memory.

Differentiating “worse” and “worst” demands deliberate cognitive effort. It compels us to consider the scope of comparison—two entities versus three or more. This precise application enhances grammatical accuracy and hones analytical skills, reinforcing pathways for careful judgment and nuanced understanding—central qualities for overall cognitive sharpness.

Read more about: The 12 Unmistakable Signs: Identifying the Worst Companies to Work For Based on Employee Reviews

4. **Grasp comparative adjectives.**

To master “worse” versus “worst,” understanding comparative adjectives is essential. These linguistic tools compare two things, indicating one possesses a quality to a greater or lesser degree. Grasping their function is a core component of linguistic intelligence, enabling clear, direct comparisons reflecting sharp relational understanding.

The general rule for comparatives involves adding “-er” (e.g., “faster”) or preceding with “more” or “less” (e.g., “more impressive”). This pattern is straightforward for regulars. The cognitive activity lies in recalling and applying these rules consistently, strengthening memory for grammatical structures and logical language reasoning.

“Worse” is an irregular comparative adjective, deviating from standard formation. It serves the same function of comparing two things. Correctly using “worse” in sentences like “Your breath is bad, but mine is worse” demonstrates adeptness in navigating linguistic irregularities—a skill refining pattern recognition and memory recall.

Read more about: Mastering ‘Worse’ vs. ‘Worst’: Your Essential Guide to Navigating Tricky Comparisons in Customer Service Evaluations

5. **Grasp superlative adjectives.**

Complementing comparatives is the concept of superlative adjectives. Where comparatives deal with two, superlatives elevate comparison to a higher degree, used “to compare more than two things… or state that something is the most extreme out of every possible option.” This precision requires identifying the ultimate degree of a quality within a broader context.

Standard superlative formation typically involves adding “-est” (e.g., “fastest”) or using “most” or “least” before the adjective (e.g., “most impressive”). This provides a consistent framework for expressing extremes. Engaging with these rules solidifies understanding of linguistic hierarchies and strengthens the ability to convey extremes accurately.

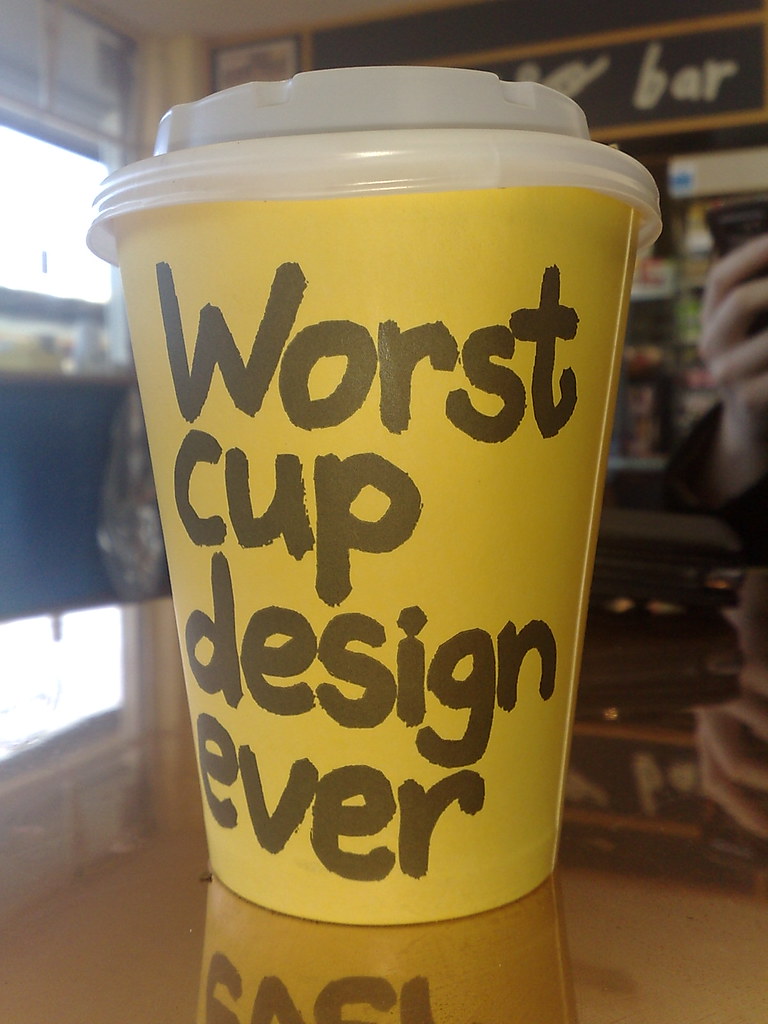

“Worst” functions as the superlative of “bad.” Its correct application, as in “his is the worst” or “the worst meal I’ve ever eaten,” requires understanding that more than two items are evaluated, or an absolute extreme is stated. The “est” remnant can be a valuable memory cue. This rule refines attention to detail and reinforces mental pathways for precise, nuanced language use.

Read more about: Mastering ‘Worse’ vs. ‘Worst’: Your Essential Guide to Navigating Tricky Comparisons in Customer Service Evaluations

6. **Recognize irregular forms of ‘bad’.**

A unique cognitive challenge with “worse” and “worst” is their status as irregular forms of “bad.” Unlike most adjectives that follow predictable patterns, “bad” transforms into “worse” and “worst.” This irregularity demands a specific kind of memory and recall, as it deviates from established linguistic rules.

The text notes, “Worse and worst don’t follow these rules.” This means our brains cannot simply apply an algorithm; they must store and retrieve these specific transformations. Remembering exceptions and applying them correctly is a powerful cognitive exercise, strengthening associative memory—linking “bad” directly to “worse” and “worst” despite lacking a conventional morphological connection.

The retention of such irregular forms, including parallel examples like “good,” “better,” and “best,” testifies to our brain’s capacity for complex linguistic storage. Actively practicing and reinforcing these forms robustly exercises episodic and semantic memory systems, crucial for maintaining overall mental agility and resisting precise language application erosion.

Read more about: The 12 Worst Stadium Naming Rights Deals: Decoding Corporate Fails and Linguistic Landmines

7. **Use ‘worse’ for comparing two things.**

The fundamental application of “worse” centers on its role in comparing precisely two distinct entities or states. This specific usage is a cornerstone of accurate communication and a vital indicator of a sharp, detail-oriented mind. When we use “worse,” we signify a decline in quality, desirability, or condition when juxtaposed against a single other item.

As the context states, “Worse is used when making a comparison to only one other thing.” This rule is non-negotiable. Consider the example: “I think the pink paint looks worse on the wall than the red paint did.” The comparison is limited to two colors. Similarly, “Jacob had a worse case of bronchitis than Melanie did,” strictly evaluates Jacob’s condition against Melanie’s.

Adhering to this precise application of “worse” is a cognitive discipline. It requires careful attention to the number of items under consideration, preventing the common mistake of using “worst” where only two are involved. This constant vigilance, ensuring our language precisely mirrors our comparisons, actively hones analytical skills and solidifies memory for specific linguistic rules, contributing significantly to overall cognitive sharpness.

Read more about: Navigating the Nuances: 11 Critical Distinctions Between ‘Worse’ and ‘Worst’ for Accurate Health Understanding

8. **Apply ‘worst’ for comparing more than two things.**

Building on the precision required for ‘worse’, cognitive sharpness also means correctly deploying ‘worst’ when the comparison involves a broader scope. Where ‘worse’ serves to differentiate between just two entities, ‘worst’ steps in when three or more items are being evaluated, pinpointing the absolute lowest quality or most negative state within that larger group. This discernment is vital for accurate communication and reflects a key aspect of linguistic mastery.

As clearly articulated in the provided context, “Worst is used in comparisons of more than two things,” and “Worst is used to compare a group of things (three or more) and translates to the lowest quality, the least desirable condition, or the most negative among them.” This foundational rule helps us identify the extreme. For instance, in a scenario involving multiple choices, stating “Yours is bad, mine is worse, but his is the worst” effectively ranks the three options, showcasing a mastery of superlative comparison.

Furthermore, ‘worst’ is not merely for ranking; it also indicates an ultimate extreme out of every possible option, even without explicitly listing all options. The context illustrates this with “That was the worst meal I’ve ever eaten,” implying it’s the most unpleasant among all meals ever consumed. This comprehensive application of ‘worst’ requires a sharp mind capable of abstracting an entire category to identify the absolute bottom, a crucial cognitive skill.

Read more about: The 12 Grammar Mix-Ups You Voted Worst: Why These ‘Worse’ & ‘Worst’ Errors Are Best Avoided

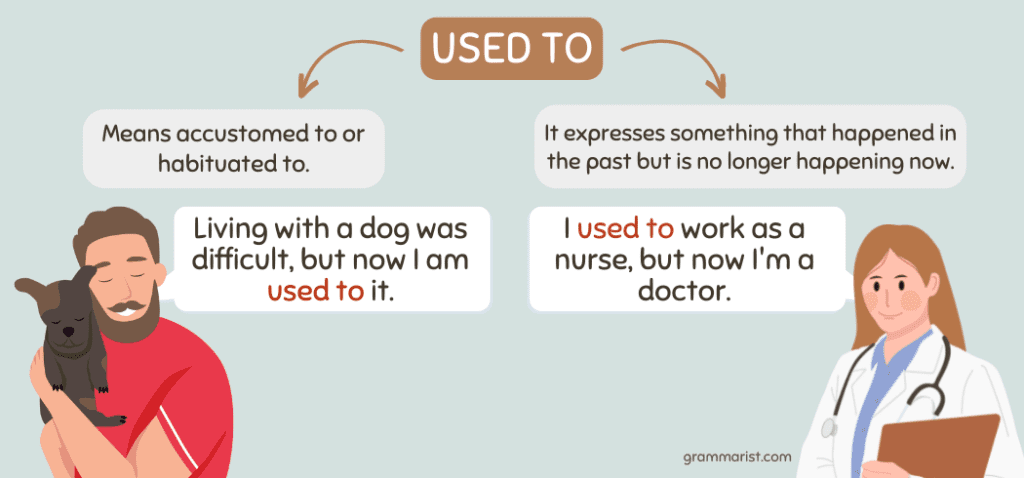

9. **Understand ‘worse’ in the idiom “from bad to worse”.**

Beyond direct comparisons, our cognitive agility is tested by idiomatic expressions where ‘worse’ takes on a specific, non-literal meaning. One such crucial idiom is “from bad to worse,” which vividly describes a situation that began unfavorably and has continued to deteriorate. Recognizing and correctly applying this phrase reflects a nuanced understanding of language and context, essential for clear and precise communication.

The phrase “from bad to worse” signifies a progressive decline in quality or condition. The context explicitly states this meaning: “Worse is used in the expression from bad to worse, which means that something started bad and has only deteriorated in quality or condition.” This isn’t about comparing two distinct bad things, but rather charting a downward spiral over time. It’s a powerful and concise way to convey ongoing deterioration, fostering efficiency in communication.

Consider the example, “My handwriting has gone from bad to worse since I graduated high school.” This sentence perfectly encapsulates the deteriorating trend, requiring the brain to process the initial ‘bad’ state and then the subsequent, even more ‘bad’ state. Using ‘worse’ here, rather than ‘worst’, accurately portrays this continuous downward trajectory, reinforcing the idea of a worsening condition from one point to another and demonstrating refined linguistic judgment.

Read more about: Navigating the Nuances: 11 Critical Distinctions Between ‘Worse’ and ‘Worst’ for Accurate Health Understanding

10. **Clarify ‘worst case’ vs ‘worse case’ in idiomatic expressions.**

Navigating common idioms often presents specific linguistic traps, and the phrase involving ‘case’ is a prime example where ‘worst’ is exclusively appropriate. Understanding why “worst case” and “worst-case scenario” are correct, while “worse case” is not, is a mark of precise cognitive processing and careful adherence to established usage, safeguarding against miscommunication.

The context unequivocally states, “The phrase worst case is used in the two idiomatic expressions: in the worst case and worst-case scenario.” Both of these idioms refer to the absolute most negative outcome possible. They describe “a situation that is as bad as possible compared to any other possible situation,” which inherently calls for the superlative form. Using ‘worst’ conveys that no other potential outcome could be more dire, a critical distinction for conveying extreme possibilities.

For example, “In the worst case, the beams will collapse instantly,” or “This isn’t what we expect to happen—it’s just the worst-case scenario.” These sentences clearly indicate the extreme, most undesirable possibility. While the words ‘worse’ and ‘case’ can certainly appear together in a sentence, as in “Jacob had a worse case of bronchitis than Melanie did,” this is not an idiom but a direct comparison of two individual ‘cases’. The ability to differentiate between these usages demonstrates sharp linguistic discrimination and attention to detail.

Read more about: Deconstructing Failure: Understanding ‘Worst’ in Business and Celebrity Ventures

11. **Navigate the idiom “if worse comes to worst” vs “if worst comes to worst”.**

Another fascinating linguistic challenge that requires cognitive precision is the expression used to describe the occurrence of the most unfavorable outcome. There are two very similar versions: “if worse comes to worst” and “if worst comes to worst.” While both convey the same meaning, their usage patterns and the subtle implications highlight the importance of linguistic awareness for cognitive sharpness and adaptable communication.

The context acknowledges both versions, stating, “There are actually two very similar versions of the expression that means ‘if the worst possible outcome happens’: if worse comes to worst or if worst comes to worst.” Interestingly, it notes that “if worst comes to worst is much more commonly used (even though it arguably makes less sense).” This observation itself demands a cognitive flexibility to accept common usage even when strict logic might suggest otherwise, reflecting a pragmatic approach to language.

Regardless of the chosen form, the idiom invariably anticipates a dire situation and is typically followed by a contingency plan. For instance, “If worse comes to worst and every door is locked, we’ll get in by opening a window.” Or, “I’m going to try to make it to the store before the storm starts, but if worst comes to worst, I’ll at least have my umbrella with me.” The precise application of these phrases, despite the slight variation in commonality, shows an acute understanding of how to plan for and communicate about potential maximal adversity, a valuable cognitive trait.

Read more about: Unpacking ‘Worst’: The Language of Financial Ruin and Celebrity Real Estate Disasters

12. **Recognize ‘worst’ as a noun and its various superlative meanings.**

The word ‘worst’ isn’t confined to its role as a superlative adjective; it also functions as a noun, enriching our language and demanding a flexible understanding from our cognitive processes. When used as a noun, ‘worst’ refers to “something that is worst” or “that which is worst,” encapsulating the most undesirable element or situation without explicitly naming it.

For instance, the context explains that ‘worst’ as a noun can be used in phrases like “Prepare for the worst,” implying preparation for the most severe possible outcome. This demonstrates the brain’s capacity to conceptualize an extreme negative state as a standalone entity, enhancing abstract reasoning. Moreover, it can signify “the least good or most inferior person, thing, or part in a group, narrative, etc.” – highlighting its abstract use in identifying the bottom tier with a single word.

Beyond this, ‘worst’ as a noun encompasses several nuanced superlative meanings, such as “the most faulty or unsatisfactory,” “most unpleasant, unattractive, or disagreeable,” or “least efficient or skilled.” Examples include “the worst job I’ve ever seen” or “the worst drivers in the country come from that state.” Recognizing these varied applications as a noun underscores the depth of linguistic comprehension and the ability to extract specific extreme qualities from broad contexts.

Read more about: The 12 Grammar Mix-Ups You Voted Worst: Why These ‘Worse’ & ‘Worst’ Errors Are Best Avoided

13. **Understand ‘worst’ as an adverb.**

Further showcasing the versatility of ‘worst’ and challenging our cognitive precision, the word can also serve as an adverb. In this capacity, ‘worst’ modifies verbs or other adverbs, describing an action or manner as being executed “in the worst manner” or “in the greatest degree.” This adds another layer of complexity to its usage, requiring attention to word function within a sentence for accurate interpretation.

The context provides definitions for ‘worst’ as an adverb, stating it means “in the worst manner” and “in the greatest degree.” It is the superlative of ‘badly’. This distinction is critical because it shifts the focus from describing a noun to describing how an action is performed, which requires a different grammatical and cognitive application. For example, if someone performs an action ‘worst’, it implies they did it in the most deficient or unsatisfactory way possible compared to others.

While explicit sentence examples for ‘worst’ as an adverb are less numerous in the provided text than for its adjective or noun forms, the underlying principle is clear. It demands our cognitive systems to recognize adverbial modification and apply the superlative degree to actions. Grasping this nuanced grammatical function demonstrates a comprehensive command of English, which directly correlates with maintaining linguistic and cognitive sharpness by constantly analyzing word roles.

Read more about: Beyond the Brakes: 11 ‘Worst’ Misconceptions Mechanics Wish You’d Stop Trusting

14. **Reinforce application through comprehensive examples of ‘worse’ and ‘worst’.**

The ultimate test and reinforcement of cognitive sharpness in distinguishing ‘worse’ and ‘worst’ lies in their consistent and accurate application across diverse sentences. Practical examples serve as invaluable tools, solidifying theoretical understanding and transforming it into intuitive linguistic competence. Regularly engaging with varied sentence structures helps engrain the rules into memory, making correct usage second nature.

The context offers a rich array of examples that effectively illustrate the precise usage of both words. For ‘worse’, we see instances like, “I think the pink paint looks worse on the wall than the red paint did,” a clear two-item comparison. Another, “Briony’s cold got worse after a few days, so she had to see a doctor,” demonstrates deterioration over time. Each example reinforces the comparative nature of ‘worse’, strengthening recall.

Similarly, for ‘worst’, the examples span various scenarios: “Out of all of us, Tom had the worst case of poison ivy,” comparing more than two. “That was the worst meal I’ve ever eaten,” conveying an absolute extreme. And, “He is the worst runner on the team,” highlighting inferiority within a group. By actively reviewing and internalizing these real-life applications, we can consistently manage stress related to linguistic precision and keep our cognitive faculties exceptionally sharp, fostering a clearer thinking process.

As we conclude this exploration, it becomes unequivocally clear that maintaining a sharp memory and robust cognitive health is a multifaceted endeavor. It’s not merely about avoiding certain physical habits but also about cultivating a meticulous approach to language and thought. By consciously implementing the strategies discussed—from active movement to the precise application of comparative and superlative adjectives like ‘worse’ and ‘worst’—we equip our brains with the resilience needed to thrive. Embrace these actionable insights, and empower your mind to navigate life’s complexities with clarity, confidence, and enduring sharpness, ensuring a future where your memory remains a steadfast ally.