There’s a captivating allure to the idea of an “untold history,” a narrative awaiting discovery beneath the familiar surface of events and objects around us. Our world is layered with the past, from grand national sagas to intricate stories within cultural artifacts. Uncovering these hidden narratives is more than curiosity; it’s a rigorous academic pursuit demanding a specialized toolkit and methodical approach.

The quest to illuminate the past is the very essence of history as an academic discipline. Far from being a mere collection of dates, history systematically studies human experience. Through a disciplined lens, it moves beyond chronology to analyze evidence, constructing narratives that not only recount events but also explain their underlying causes and contextual significance. This intricate process transforms “what happened” into a dynamic understanding of “why it happened.”

To truly bring an “untold history” to light requires understanding the fundamental principles guiding historians. From meticulously examining raw evidence to synthesizing diverse perspectives, the historian employs comprehensive techniques. This article explores 14 essential elements of the historian’s toolkit, starting with the discipline itself and the crucial methods of source evaluation that form the bedrock of credible historical inquiry.

1. **History as an Academic Discipline**At its core, history stands as the systematic study of the past, primarily focusing on the human journey. As an academic discipline, it meticulously collects and analyzes evidence to construct narratives. These accounts delve into how events developed over time, critically examining *why* they transpired and within *which* contexts, offering profound explanations of relevant background conditions and causal mechanisms. Ultimately, history also scrutinizes the meaning of these events and the underlying human motives that propelled them.

Historians engage in an ongoing debate about whether their field aligns more closely with the social sciences or the humanities. Like social scientists, they formulate hypotheses and gather objective evidence to support arguments. Yet, history also deeply resonates with the humanities, embracing subjective aspects like interpretation, storytelling, human experience, and cultural heritage. Many scholars characterize it as a hybrid discipline, uniquely positioned to blend empirical rigor with profound humanistic insights.

Fundamentally, history transcends mere chronology, distinguishing itself from chronicles that simply catalogue events. A true historical narrative aims for a comprehensive understanding of causes, contexts, and consequences. This active interpretation and reconstruction of the past allows for narratives that can evolve as new evidence emerges or existing sources are reinterpreted, making the past a dynamic and ever-unfolding field of study.

Read more about: The 12 Best Books on US History Every Citizen Should Read: Unpacking America’s Past Through Essential Reads

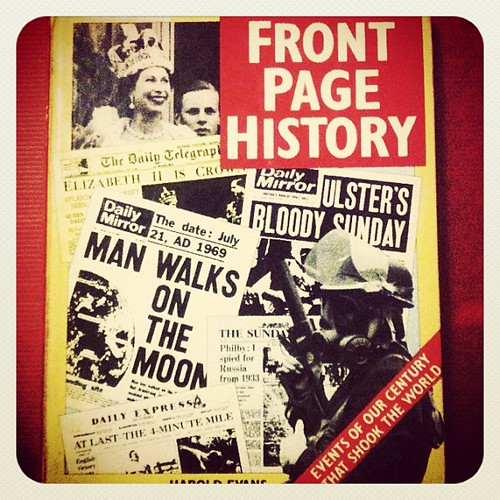

2. **The Dual Nature of Historical Sources: Primary and Secondary**Any historical investigation rests on the foundation of evidence, which historians meticulously employ to reconstruct past events and validate their interpretations. This evidence is systematically divided into primary and secondary sources, each offering a distinct yet vital perspective on bygone eras. Understanding this fundamental distinction is crucial for any rigorous engagement with the past.

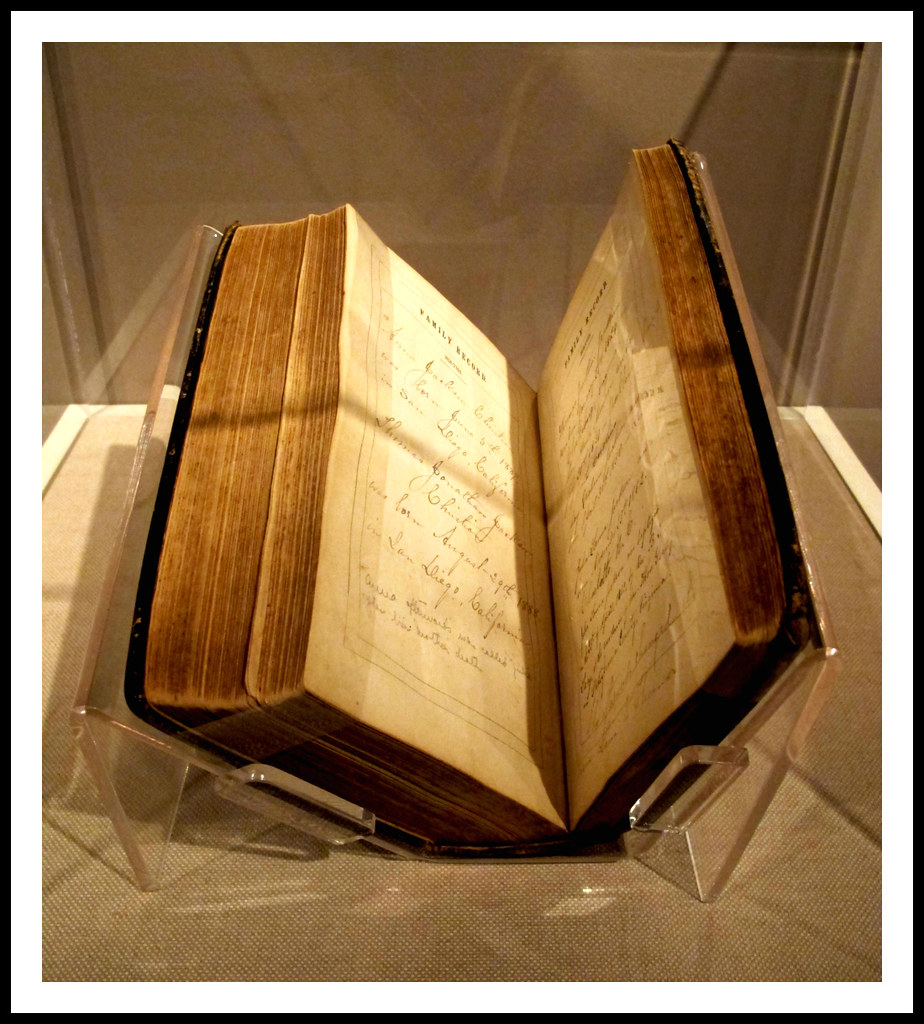

Primary sources are materials that originated directly during the period under investigation. These immediate windows into the past can manifest in myriad forms, including official documents, personal letters, diaries, and eyewitness accounts. They also encompass photographs, audio recordings, and even physical remnants like artifacts and fossils unearthed through archaeology or geology. These sources offer the most direct, unfiltered testimony of historical events, providing invaluable insights into contemporary perspectives and realities.

In contrast, a secondary source analyzes or interprets information already found in other sources, typically primary ones. Scholarly articles, textbooks, and biographies are classic examples. The classification of a source, however, is often fluid and depends on its specific use. For instance, a historian’s essay on a past conflict serves as a secondary source regarding that conflict, but it becomes a primary source if one is studying the historian’s own views or methodology. This nuanced understanding is essential for discerning the role and value of each piece of evidence.

Read more about: Political Intrigue: Unpacking the 14 Reasons Why Prominent Figures Are Steering Clear of Presidential Endorsements

3. **Ensuring Authenticity: The Art of External Source Criticism**Before any deep dive into the narrative a source presents, historians must first engage in external criticism, a foundational step to confirm its authenticity. This initial phase of evaluation is paramount, as the entire historical reconstruction hinges on the reliability of the evidence. Building a historical account on unverified or fabricated documents would fundamentally undermine its credibility.

Before any deep dive into the narrative a source presents, historians must first engage in external criticism, a foundational step to confirm its authenticity. This initial phase of evaluation is paramount, as the entire historical reconstruction hinges on the reliability of the evidence. Building a historical account on unverified or fabricated documents would fundamentally undermine its credibility.

External criticism systematically probes critical questions about a source’s origin. This includes determining its creation date and location, identifying the author, and understanding their motivations for producing the document. Furthermore, it involves scrutinizing whether the source has undergone any modifications since its original creation, which could potentially alter its integrity or meaning. A key aspect is distinguishing between original works, faithful copies, and deliberate forgeries, tasks that often demand specialized expertise in areas like archival science.

This meticulous examination of a source’s external attributes is an indispensable safeguard. By rigorously verifying that a document is what it claims to be and understanding its lineage, historians establish a secure foundation for subsequent analysis. This initial validation protects against misinformation and ensures that all interpretations are grounded in genuinely historical materials, preserving the integrity of scholarly inquiry.

Read more about: Beyond the Podium: Unpacking Why Hollywood’s Political Biopics So Often Miss the Mark

4. **Evaluating Content: Navigating Internal Source Criticism for Accuracy**With a source’s authenticity established, historians proceed to internal criticism, a profound analytical process focused on assessing the content’s accuracy and reliability. This stage shifts from the ‘what it is’ to the crucial ‘what it says’ and ‘how trustworthy it is,’ ensuring that historical narratives are built upon precise and comprehensive data, not merely authentic documents.

Internal criticism typically begins by clarifying the meaning within the source. This involves disambiguating terms that might be easily misunderstood due to evolving language or specialized historical contexts. If the source is in an unfamiliar language, accurate translation is a prerequisite. Achieving this initial semantic clarity is vital, as any misinterpretation at this stage can lead to fundamental errors in subsequent historical analysis.

Following clarity, the focus intensely shifts to determining accuracy. Critics ask whether the information reliably represents the topic or if it misrepresents it. They also question if the source is comprehensive or if important details have been omitted. Assessments often involve evaluating the author’s capacity to provide a faithful presentation, considering their intentions and potential biases, and cross-referencing with other credible sources. Recognizing inherent limitations helps historians judiciously decide how to integrate the source into a coherent and trustworthy narrative.

5. **The Craft of Historical Synthesis: Weaving Evidence into Coherent Narratives**The rigorous processes of source selection, analysis, and criticism typically yield a collection of distinct statements and fragments of evidence about the past. The subsequent, crucial stage for historians is historical synthesis, where these individual pieces are meticulously examined to reveal how they interconnect and form part of a larger, cohesive story. This phase represents a creative pinnacle of historical writing, transforming disparate facts into comprehensive understanding.

Constructing this broader perspective is absolutely essential for a holistic grasp of any historical topic. It moves beyond merely identifying *which* events occurred to unraveling *why* they happened and *what consequences* they precipitated. This process involves reconstructing, interpreting, and explaining the past by demonstrating the intricate connections between different events, motives, and contexts. It is here that the historian truly builds an explanatory framework, giving shape and meaning to the vastness of collected data.

While no universally accepted technique exists for synthesis, historians deploy a diverse array of interpretative tools. This creative endeavor demands deep knowledge of the subject matter and a nuanced understanding of human behavior and societal dynamics. By artfully weaving validated evidence, historians craft narratives that illuminate the complex tapestry of the past, offering insights that are both informative and profoundly enlightening.

6. **The Enduring Debate: Uncovering Truth vs. Learning Lessons from the Past**The very purpose and value of history have long been subjects of profound philosophical debate among scholars. This discussion often centers on two prominent perspectives: whether history’s primary function is the disinterested pursuit and discovery of truth about the past, or if its main value lies in the practical lessons it offers for the present and future. Each perspective highlights distinct, yet interconnected, facets of historical inquiry.

One significant view emphasizes that the pure discovery of truth is an end in itself, a fundamental academic objective. Proponents argue that external purposes, such as political or ideological agendas, inherently risk undermining historical accuracy by distorting the past. In this role, history serves as a powerful tool to challenge traditional myths lacking factual support, ensuring our understanding is grounded in verifiable evidence rather than convenient narratives.

A contrasting perspective posits that history’s principal value resides in the lessons it imparts for contemporary decision-making. This view suggests that understanding past events can guide present actions, particularly in helping to avoid repeating previous mistakes. Furthermore, history can foster a broader understanding of the human condition, making people aware of the rich diversity of human behavior across different contexts, much like visiting foreign countries broadens one’s perspective. Both the pursuit of truth and the extraction of lessons underscore the profound and multifaceted utility of historical study.

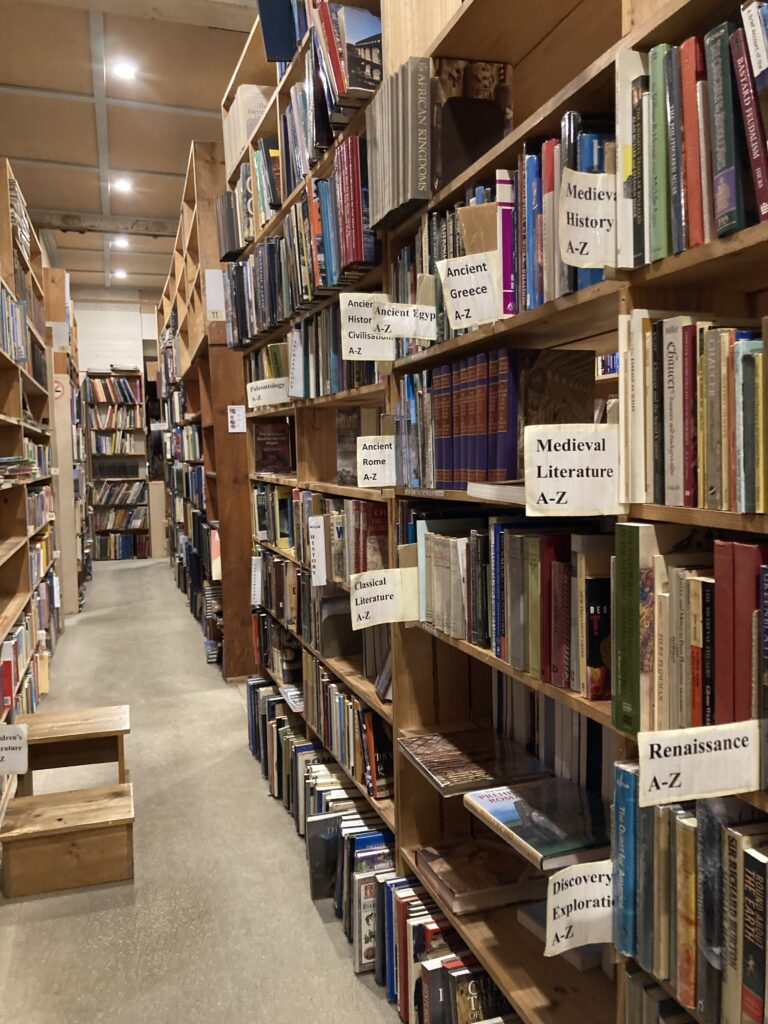

7. **Structuring Time: The Methodological Power of Periodization**To navigate the immense and continuous expanse of human history, historians employ periodization, a crucial methodological tool that divides timeframes into more manageable segments. This organizational approach is not arbitrary; rather, different periods are typically defined by dominant themes, significant events, or transformative developments that characterize a specific era. This allows for a more focused and comprehensive study of distinct historical epochs.

Periodization provides an accessible overview of complex historical developments, enabling scholars and students alike to grasp overarching patterns and shifts within particular eras. The duration of a period can vary widely, from a mere decade to several centuries, depending on the chosen context and level of detail. For instance, early human history is traditionally segmented into the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age, based on the prevalent materials and technologies of those times.

It is important to recognize that periodizations are not universal and can vary significantly across different regions and thematic studies. Traditional Chinese history, for example, often follows the main dynasties, while the history of the Americas is commonly divided into pre-Columbian, colonial, and post-colonial periods. This adaptability underscores periodization’s utility as an interpretative framework, allowing historians to impose structure on the flow of time and highlight key transitions that shaped human experience.

While the foundational elements of historical inquiry — the discipline itself, source classification, criticism, synthesis, understanding its purpose, and periodization — provide a robust framework, the academic field of history is far from monolithic. It thrives on a rich tapestry of advanced methodological approaches, diverse schools of thought, and specialized thematic branches, each offering unique lenses through which to examine and interpret the past. These varied perspectives not only enrich our understanding but also allow historians to tackle complex questions, uncover hidden narratives, and continually refine the discipline’s rigor and relevance.

Moving beyond the initial toolkit, we now delve into seven additional foundational elements that equip historians to navigate the complexities of human experience. From embracing distinct theoretical outlooks that shape interpretation to employing innovative methods for data analysis and exploring focused thematic areas, these approaches expand the scope and depth of historical understanding. They demonstrate how history remains a dynamic field, constantly evolving its methods to reconstruct the past with greater precision, insight, and comprehensive awareness.

8. **Positivism: The Scientific Pursuit of Objective Truth**Among the various schools of thought that have profoundly influenced historical inquiry, positivism stands as a testament to the aspiration for scientific rigor in the study of the past. Articulated by figures like Auguste Comte, positivists emphasize the scientific nature of historical inquiry, advocating for an approach that mirrors the natural sciences. Their core belief centers on the discovery of objective truths about the past, grounded firmly in empirical evidence.

This school of thought contends that history, like other scientific disciplines, should rely on verifiable facts and observable phenomena to construct narratives. Proponents of positivism believe that external purposes, such as political or ideological agendas, can inherently undermine the accuracy of historical research. By prioritizing the disinterested pursuit of truth, they argue, historians can ensure that their understanding is based on verifiable evidence rather than convenient or biased narratives.

In essence, positivism aims to establish history as a discipline capable of uncovering universal laws or patterns in human societies, much like physics seeks to understand the laws of the universe. This perspective emphasizes a methodical collection and analysis of evidence, striving to eliminate subjective interpretations and personal biases, thereby presenting a ‘true’ and unadulterated account of past events.

9. **Postmodernism: Deconstructing Grand Narratives and Embracing Subjectivity**In stark contrast to positivism, postmodernism emerged as a powerful counter-narrative, challenging the very notion of a single, objective historical truth. This school of thought rejects the idea of “grand narratives” that claim to offer a unified, all-encompassing explanation of the past. Instead, postmodernists highlight the inherently subjective nature of historical interpretation, arguing that every historical account is shaped by the historian’s perspective, cultural context, and linguistic framework.

Postmodern historians contend that language itself is not a transparent window to the past but rather a medium that constructs meaning, and therefore, reality. This leads to a multiplicity of divergent perspectives, where no single interpretation can claim absolute authority. They encourage skepticism towards universal claims and an awareness of how power structures influence which histories are told and how they are received.

By deconstructing traditional narratives and emphasizing the role of interpretation, postmodernism has broadened the scope of historical inquiry to include marginalized voices and alternative experiences. It encourages historians to critically examine their own biases and the constructed nature of historical knowledge, ultimately enriching the discipline by fostering a more nuanced and self-aware engagement with the past.

10. **The Examination of Silences: Uncovering Omissions in the Historical Record**Beyond analyzing explicit documents, historians employ sophisticated methodological tools to detect and interpret what is *not* present in the historical record—a crucial approach known as the examination of silences. These silences represent gaps or omissions in documented history, instances of events that undoubtedly occurred but left no significant evidential traces or were deliberately suppressed. This technique is vital for reconstructing more complete and inclusive narratives.

Silences can arise for various reasons. Sometimes, contemporaries found certain information too obvious or mundane to document, leading to an unintentional void in records. In other cases, there might have been specific motivations to withhold or even destroy information, often due to political, social, or personal sensitivities. Uncovering these deliberate omissions requires a keen critical eye and an understanding of power dynamics within historical contexts.

By actively seeking out and interrogating these silences, historians can shed light on marginalized groups, suppressed events, or everyday experiences that were previously overlooked. This method compels scholars to move beyond readily available documents and infer historical realities from the absence of evidence, thereby enriching our understanding of the unspoken and untold aspects of the past.

11. **Quantitative History: Statistical Analysis of Large Datasets**For periods and topics where extensive data is available, historians increasingly employ quantitative approaches, transforming raw numerical information into meaningful historical insights. Quantitative history utilizes statistical analysis to identify patterns, trends, and correlations associated with large groups of people, economic activities, or social phenomena. This method brings a scientific, data-driven dimension to historical inquiry.

This methodology is particularly valuable for economic and social historians who seek to understand broad, impersonal forces such as inflation, demographic shifts, or the distribution of wealth. By analyzing large datasets – from census records and trade figures to church registers and property deeds – historians can move beyond anecdotal evidence to present statistically significant conclusions about past societies. This allows for a more rigorous and evidence-based understanding of large-scale historical processes.

However, the application of quantitative methods is not without its challenges, especially for periods predating the modern era where data can be scarce or incomplete. Historians must often extrapolate information from limited sources and meticulously verify the reliability of their numerical evidence. Despite these hurdles, quantitative history remains an indispensable tool for uncovering macro-level trends that profoundly shaped human experience.

12. **Oral History: Personal Experiences and Memories**While traditional historical inquiry has often prioritized written documents, oral history offers a vital alternative, relying on spoken testimonies to reconstruct the past. This methodological branch encompasses eyewitness accounts, hearsay, and communal legends, capturing the personal experiences, interpretations, and memories of individuals and communities. It provides a unique window into subjective understandings of historical events.

Oral history is particularly powerful for giving voice to individuals or groups whose experiences might be absent from official written records, such as marginalized communities, everyday people, or those impacted by events not deemed significant by chroniclers. It reflects how people subjectively remember the past, revealing nuances, emotions, and cultural contexts that purely factual accounts might miss. These personal narratives add depth and a human dimension to historical analysis.

The collection of oral histories involves careful interviewing techniques and critical evaluation, as memory can be fallible and narratives shaped by present-day perspectives. Historians must cross-reference these accounts with other forms of evidence to ensure reliability. Despite these considerations, oral history remains a crucial method for capturing living history, preserving cultural heritage, and understanding the multifaceted ways in which the past is experienced and remembered.

Read more about: When the Red Carpet Rolled Out Chaos: 14 Unforgettable Award Show Moments That Blew Our Minds

13. **Thematic Branches: Political, Economic, and Social History**Beyond chronological or geographical divisions, historians often narrow their inquiry to specific themes, allowing for deep dives into particular aspects of human experience. Among the most foundational of these thematic branches are political, economic, and social history, each offering a distinct lens for understanding societal development. These broad categories, while interconnected, enable specialized analysis.

Political history, one of the oldest branches, studies the organization of power in society. It examines how states and political institutions arise, develop, and interact internally and externally, focusing on policies, leaders, parties, and international relations. Diplomatic and military history are closely associated sub-fields, exploring interstate relations and armed conflicts, respectively, including technological advancements and strategic considerations.

Economic history investigates the production, exchange, and consumption of commodities, covering aspects like land use, labor, capital, supply and demand, and wealth distribution. It often focuses on impersonal forces like inflation and employs quantitative methods. Social history, a broad field, explores social phenomena such as everyday life, cultural practices, family structures, community interactions, and the experiences of specific social groups (e.g., classes, genders, races), or even societal problems like poverty and crime. These thematic explorations allow for comprehensive insights into the multifaceted nature of human history.

Read more about: The United States: A Complex Legacy of Discord and Unity, Shaping a Nation’s Evolving Identity

14. **World History and Microhistory: Varying Scales of Historical Inquiry**The scale at which history is studied also constitutes a foundational element of its methodology, ranging from the grandest global narratives to the most intimate local investigations. World history and microhistory exemplify these contrasting approaches, each offering unique insights into the human past by adjusting the analytical lens. These varying scopes allow historians to identify patterns at different levels of complexity and detail.

World history encompasses human history as a whole, often starting with the evolution of human-like species and examining interconnected developments across continents. It seeks to understand global patterns, cross-cultural exchanges, and broad processes that transcend regional boundaries. This macro-level approach helps to contextualize localized events within a broader human narrative, emphasizing interconnectedness rather than isolation.

Conversely, microhistory focuses on incredibly detailed studies of local contexts, small communities, family histories, particular individuals, or specific events. It uses a narrow focus to illuminate broader historical processes, often uncovering the nuanced experiences of ordinary people and the intricate workings of power and culture at a local level. Closely related to microhistory is the genre of historical biography, which recounts an individual’s life within its historical context and examines their legacy. These diverse scales of inquiry ensure that history remains a comprehensive discipline, capable of addressing both the universal and the particular in the human journey.

In embracing these advanced methodologies, diverse schools of thought, and specialized thematic branches, the discipline of history continuously refines its ability to tell the “untold history” of our world. From rigorously scientific quests for objective truth to profound acknowledgements of subjectivity and interpretation, from scrutinizing grand global patterns to meticulously detailing individual lives, historians continue to expand their toolkit. This ongoing evolution ensures that our understanding of the past is not a static collection of facts, but a dynamic, ever-enriching dialogue that deepens our collective human awareness and illuminates the intricate tapestry of historical experience.