Summer is a time when many of us enthusiastically embrace the ritual of grilling, eager to savor those distinct smoky flavors and perfectly seared textures. From juicy burgers to sizzling hot dogs and an array of vegetables, charred foods have become a beloved staple in the American diet, often taking center stage at summertime gatherings. However, beneath the tempting aroma and taste, a growing body of scientific research is uncovering potential health implications, particularly concerning cancer risks, that warrant our careful attention. It’s time to understand what’s really happening when our food gets that signature char.

Oncology researchers and cancer epidemiologists are laser-focused on understanding how everyday habits, like the foods we eat and how we prepare them, may impact our health in ways we never expected. Their studies consistently point to specific chemical compounds—heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—that form when muscle meats are cooked at high temperatures. These substances have been found to be mutagenic, meaning they cause changes in DNA that could increase the risk of cancer.

This in-depth exploration will demystify the science behind these potential risks, illuminate the critical factors influencing their formation, and present the evidence from both laboratory and population studies. Our aim is to empower you with credible, accessible information so you can make informed choices, enjoy your grilling season responsibly, and take proactive steps toward a healthier, longer life.

1. **Understanding Heterocyclic Amines (HCAs)**Heterocyclic amines, or HCAs, are a class of chemical compounds that are primarily formed when muscle meat—this includes beef, pork, fish, or poultry—is cooked using high-temperature methods. Think about your favorite pan-fried steak or grilled chicken; these are prime scenarios for HCA formation. They are not found in significant amounts in foods other than meat cooked at high temperatures, making meat consumption a focal point for understanding exposure.

The formation of HCAs is a complex chemical reaction involving specific components found within muscle meat. Amino acids, which are the fundamental building blocks of proteins, along with sugars and creatine or creatinine—substances naturally present in muscle—react with one another when exposed to intense heat. This reaction process, which accelerates significantly at temperatures above 300°F, leads to the creation of these potentially harmful compounds. The longer meat is exposed to such high heat, the greater the accumulation of HCAs.

In laboratory experiments, HCAs have consistently been found to be mutagenic. This means they possess the capability to induce changes or mutations in DNA, the genetic material within our cells. Such DNA alterations are a recognized mechanism by which cancer can initiate and develop. It’s important to note that HCAs become capable of damaging DNA only after they are metabolized by specific enzymes in the body, a process known as “bioactivation.” The activity of these enzymes can vary among individuals, potentially influencing the cancer risks associated with HCA exposure.

Read more about: Mastering the Flame: A Comprehensive Scientific Guide to Unlocking Grilling Perfection

2. **Unpacking Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)**Alongside HCAs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) represent another significant class of chemicals formed during high-temperature cooking of muscle meats. While HCAs predominantly arise from reactions within the meat itself, PAHs are often generated through a different mechanism, largely involving the cooking environment, particularly when grilling over an open flame.

PAHs form when the fat and juices from meat drip directly onto a heated surface or an open fire. This dripping fat combusts, causing flames and smoke. The smoke produced in this process is laden with PAHs, which then adhere to the surface of the meat being cooked. This direct exposure to smoke is a primary pathway for PAH contamination in grilled foods. PAHs can also be formed during other food preparation processes, such as the smoking of meats, which is a common preservation and flavoring technique.

Similar to HCAs, PAHs have also been identified as mutagenic in laboratory experiments, indicating their potential to cause DNA changes that may contribute to cancer risk. Beyond cooked meats, PAHs are ubiquitous in our environment and can be found in other smoked foods, as well as in more concerning sources such as cigarette smoke and car exhaust fumes, underscoring their widespread presence and the various routes of human exposure. This highlights the importance of minimizing dietary intake where possible.

Read more about: Mastering the Flame: A Comprehensive Scientific Guide to Unlocking Grilling Perfection

3. **The Dangers of PhIP and its Link to Prostate Cancer**Among the various heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs), one specific chemical, PhIP, has garnered particular attention from oncology researchers, especially concerning its potential link to prostate cancer risk. PhIP, or 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine, is a type of HAA that forms when meat is cooked at high temperatures through methods like grilling, charring, or frying. It represents a concrete example of a carcinogen formed through these common culinary practices.

Previous research has indicated that consuming well-done meat, which is associated with higher levels of PhIP, may contribute to an increased risk of aggressive prostate cancer. This is a significant concern for men, given that prostate cancer affects many across the U.S., including in regions like Minnesota, where specific studies have been conducted. Understanding PhIP’s role provides a more granular look at the specific chemical culprits involved in diet-related cancer risks.

A recent study led by researcher Robert Turesky, PhD, at the Masonic Cancer Center (MCC), University of Minnesota, has further investigated PhIP. This research aimed to establish whether hair samples could serve as a reliable method for measuring PhIP exposure over time, potentially offering a more accurate assessment than traditional dietary questionnaires. Such advancements in exposure measurement are crucial for better understanding the precise link between dietary PhIP intake and cancer development, and for developing more targeted prevention strategies.

4. **High-Temperature Cooking: A Major Risk Factor**The method and duration of cooking play a paramount role in the formation of HCAs and PAHs in muscle meats. Across all types of meat—be it beef, pork, fish, or poultry—cooking at high temperatures, particularly those exceeding 300°F, significantly contributes to the generation of these carcinogens. Common cooking techniques such as grilling directly over an open flame or pan frying are identified as high-risk methods due to the intense heat they impart.

Furthermore, the length of time meat is exposed to these high temperatures is a critical factor. Prolonged cooking times tend to form more HCAs, meaning that the longer your meat sizzles and browns on the grill or in the pan, the greater the potential for harmful compound accumulation. This relationship between heat intensity, cooking duration, and carcinogen production underscores the importance of mindful cooking practices.

Beyond direct heat, cooking methods that expose meat to smoke also substantially contribute to PAH formation. As fat and juices drip onto a hot surface or open fire, they combust, creating smoke. This smoke then carries PAHs that can adhere to the meat’s surface. Therefore, techniques that generate significant smoke, such as direct flame grilling, intensify the risk of PAH exposure, making it a dual concern alongside HCA formation.

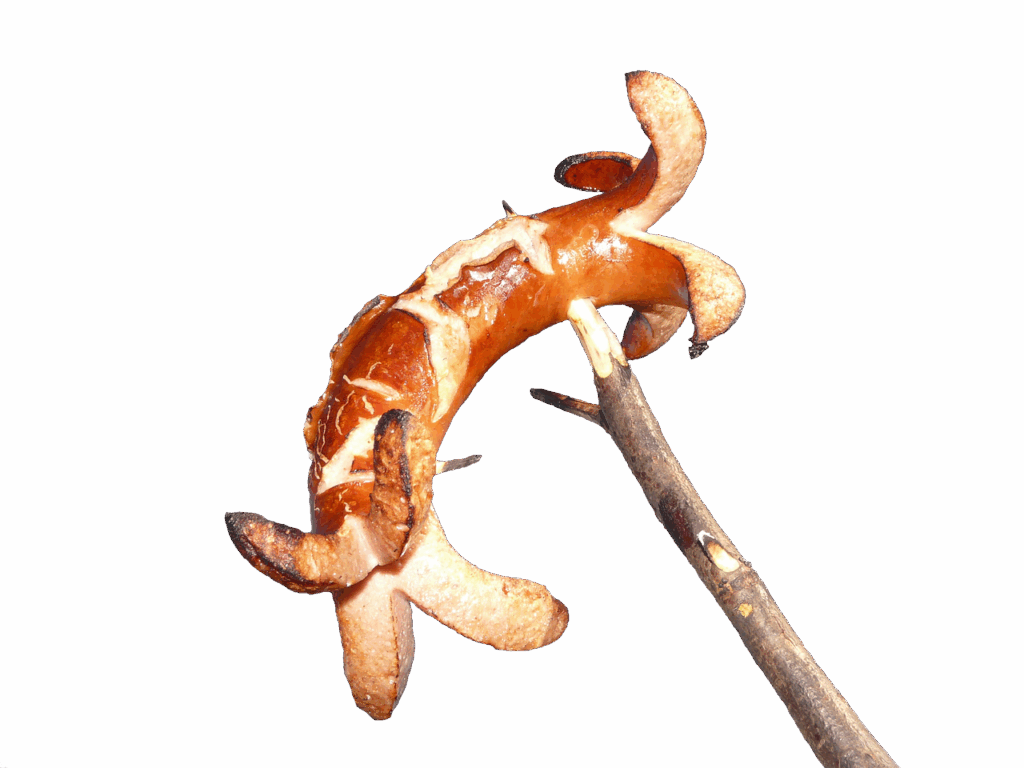

5. **The ‘Doneness’ Factor: Why Well-Done is Worse**The degree to which meat is cooked, commonly referred to as its “doneness” level, is a direct indicator of the potential concentration of HCAs and PAHs. Research consistently shows that meats cooked to a well-done stage, especially those that are grilled or barbecued, contain substantially higher levels of these carcinogens compared to their rare or medium-cooked counterparts. This is a critical insight for those who prefer their meat thoroughly cooked.

For example, studies have specifically highlighted well-done, grilled, or barbecued chicken and steak as having high concentrations of HCAs. The extensive exposure to high heat required to achieve a well-done internal temperature and the often accompanying charring on the surface directly correlate with increased carcinogen production. This visible char is not just about flavor; it’s a tangible sign of chemical reactions that produce potentially harmful compounds.

This correlation underscores why the preference for well-done or charred meats might contribute to an elevated cancer risk. The chemical transformations that create the desired crispy, browned, or blackened exterior and fully cooked interior are precisely the processes that generate HCAs and PAHs. Therefore, understanding this ‘doneness’ factor is essential for evaluating personal dietary risk and considering alternative cooking preferences or preparation methods.

6. **Animal Studies: Strong Evidence, High Doses**A significant portion of our understanding regarding the carcinogenic potential of HCAs and PAHs comes from rigorous studies conducted on animal models. These experiments have consistently demonstrated a clear link between exposure to these compounds and the development of cancer. In numerous laboratory settings, rodents that were fed diets supplemented with HCAs developed a wide array of tumors in various organs, including the breast, colon, liver, skin, lung, and prostate.

Similarly, rodents that were exposed to diets containing PAHs also exhibited increased cancer incidence. These studies reported the development of cancers such as leukemia and tumors affecting the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. The consistency of these findings across multiple studies and different tumor types provides strong mechanistic evidence that HCAs and PAHs are indeed capable of initiating and promoting cancer development.

However, it is crucial to interpret these findings with a key caveat: the doses of HCAs and PAHs administered in these animal studies were extremely high. Researchers note that these doses were “equivalent to thousands of times the doses that a person would consume in a normal diet.” While these high doses effectively demonstrate the carcinogenic potential of these compounds, they do not directly translate to the exact risk posed by typical human dietary intake. They serve as a powerful biological proof-of-concept, establishing the hazardous nature of these chemicals, even if the precise human risk from realistic exposure levels requires further investigation.

7. **Human Population Studies: The Nuance of Dietary Links**Animal studies provide compelling evidence, but translating these findings to human dietary intake requires population studies. These epidemiological studies aim to identify links between lifestyle factors, like diet, and cancer rates in humans, often using detailed dietary questionnaires. However, precisely determining exact HCA and PAH exposure levels from cooked meats is challenging, as questionnaires may not capture all cooking nuances.

Despite these complexities, numerous epidemiologic studies have linked high consumption of well-done, fried, or barbecued meats to increased risks of colorectal (19–21), pancreatic (21–23), and prostate (24, 25) cancer. These findings suggest that cooking practices and meat doneness likely play a role in human cancer development, consistently pointing to specific associations that warrant attention.

It’s important to note that not all studies have found a definitive association, with some showing no clear link with colorectal (26) or prostate (27) cancer risks. This highlights the multifactorial nature of cancer, complicated by other environmental PAH exposures. Nevertheless, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 2015 determined red meat consumption to be “probably carcinogenic to humans” (Group 2A), based largely on epidemiologic data and strong mechanistic evidence, emphasizing the cumulative impact of dietary choices.

8. **Individual Variability: How Enzymes Influence Your Risk**Beyond cooking methods, individual enzyme activity significantly influences personal cancer risk from HCAs and PAHs. These compounds don’t directly damage DNA; instead, specific enzymes in the body must metabolize them into harmful forms through “bioactivation.” This process is crucial to understanding the varying impact of exposure.

The activity levels of these metabolizing enzymes differ significantly among individuals, often due to genetic variations. Some people may have more active enzymes, processing carcinogens more efficiently into DNA-damaging forms, while others have less active enzymes, potentially offering some protection. These differences mean that even with similar meat consumption, the biological impact and subsequent cancer risk can vary widely.

Studies suggest these enzymatic variations are relevant to cancer risks associated with HCA and PAH exposure (3–9). This insight underscores why a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to dietary advice may not capture personalized risk, opening doors for future research to identify susceptible individuals and offer more targeted prevention strategies based on their unique biochemistry.

9. **Practical Strategies for Healthier Grilling**To significantly reduce exposure to HCAs and PAHs, practical, evidence-based steps focus on modifying grilling methods. These strategies aim to minimize the conditions that favor harmful chemical reactions, allowing for safer enjoyment of grilled favorites and supporting a healthier lifestyle.

One effective approach is to reduce meat’s direct exposure to extreme heat and open flames. Partially cooking meat in a microwave oven before grilling substantially reduces HCA formation by cutting down high-temperature grill time (29). Smaller cuts of food also naturally shorten cooking duration, further minimizing carcinogen production.

Active heat management during grilling is also key. Continuously turning meat over on a high heat source substantially reduces HCA formation compared to infrequent flipping (29). Cooking on indirect heat, or using grills that offer more flame control, helps prevent fat and juices from dripping onto the fire, which produces PAH-laden smoke.

Mindful preparation and consumption also make a difference. Trim excess fat from meat, as dripping fat is a primary PAH source. Marinades, especially with herbs and spices, can help reduce HCA formation. After cooking, remove charred portions, and avoid gravy made from meat drippings to further reduce exposure (29).

Cancer epidemiologist Mary Beth Terry, PhD, emphasizes moderation, suggesting not to “have four alcoholic drinks or four charred burgers at once.” This principle implies that reducing the frequency and quantity of grilled and smoked meats, rather than eliminating them entirely, lightens the burden on your body’s DNA repair mechanisms. This allows your body to more effectively “repair damage,” ultimately helping you “reduce your risk of future cancer” at any stage of life.

Read more about: Fueling Vision: The 14 Foods Ophthalmologists Strictly Limit for Optimal Eye Health and Clarity

10. **Breakthroughs from the PhIP Prostate Cancer Study**Recent research at the Masonic Cancer Center (MCC), University of Minnesota, led by Dr. Robert Turesky, provided compelling insights into PhIP, a specific HAA linked to prostate cancer. This study investigated hair samples as a reliable, long-term marker for PhIP exposure, offering a potentially more accurate assessment than traditional dietary questionnaires, which can be less reliable in capturing detailed cooking habits over time.

The study, collaborating with Dr. Logan Spector and Clarence Jones, examined hair samples from African American and European American men in Minnesota. A key finding was that men consuming more well-done, grilled, or charred meats had consistently higher PhIP levels in their hair. This directly reinforces the connection between high-temperature cooking and carcinogen exposure, providing measurable human evidence.

Crucially, the research addressed health disparities. African American men initially showed higher PhIP levels per gram of hair, though this was not statistically significant after adjusting for melanin. Still, it highlights a critical concern: African American men in Minnesota face nearly twice the prostate cancer risk compared to White men. This study suggests dietary habits, including preference for well-done meats, might contribute to these disparities.

The data indicated that about 20 percent of both groups had relatively high PhIP levels in their hair. This emphasizes that dietary habits can significantly impact cancer risk across diverse populations. The use of hair samples for long-term PhIP exposure is a valuable new tool, allowing for earlier identification of at-risk individuals and enabling more personalized prevention strategies.

11. **Broader Implications for Personalized Prevention**The accumulating evidence on charred food carcinogens and individual enzyme variability points towards increasingly personalized cancer prevention. This holistic view considers cooking methods, food choices, and individual biology, encouraging proactive risk mitigation throughout life.

Cancer epidemiologist Mary Beth Terry, PhD, emphasizes moderation: “At any stage of your life you can reduce your risk of future cancer.” Our bodies have DNA repair mechanisms, and fewer repairs mean less chance of cancer. A slower, manageable intake of carcinogens makes it “easier for your body to repair damage,” suggesting that limiting frequent, high exposures is key.

Currently, no federal guidelines specifically address HCA and PAH consumption. However, the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research recommended limiting red and processed meats, including smoked varieties (28). This aligns with the scientific understanding that continuous exposure to such foods, especially high-temperature prepared ones, is a long-term health factor.

Furthermore, individual enzyme variations mean exposure differences even among those ingesting the same amount of compounds. This supports personalized approaches. By integrating dietary habits, cooking methods, and personal risk factors like family history or occupational exposures, individuals can gain a comprehensive understanding of their vulnerability. This empowers them to make tailored decisions—like moderating grilled food and choosing less charred options—to effectively reduce their future cancer risk.

Read more about: Beyond the Snoring: Critical Sleep Apnea Indicators, Including Mood Shifts, You Must Never Overlook

12. **Embracing Holistic Care for Optimal Well-being**For those facing a cancer diagnosis, understanding lifestyle factors integrates seamlessly into holistic care, exemplified by clinics like Brio-medical Cancer Clinic. Under Dr. Nathan Goodyear’s guidance, they recognize cancer affects the entire person—mind, body, and spirit—requiring comprehensive support beyond physical symptoms.

Personalized nutrition is a cornerstone of this holistic care. Brio-medical crafts individualized plans emphasizing whole foods and natural supplements, supporting the body’s healing, reducing inflammation, and providing a balanced diet rich in antioxidants (berries, leafy greens) and fiber (whole grains, fruits, vegetables). These plans also recommend limiting processed and red meats, aligning with prevention guidelines.

Holistic care extends to advanced integrative and targeted therapies. Brio-medical offers acupuncture, massage, meditation, immunotherapy, and hyperthermia. These work with conventional treatments to optimize outcomes and minimize side effects. Targeted therapies precisely attack cancer cells while sparing healthy ones, leading to more effective and less debilitating treatments.

Crucially, emotional and psychological support is integral. Cancer profoundly impacts mental well-being, causing fear, anxiety, and depression for patients and loved ones. Brio-medical provides one-on-one counseling and support groups, offering a safe environment for sharing experiences and receiving professional guidance. This multi-faceted approach ensures care addresses all aspects of the health journey, aiming for improved quality of life and optimal outcomes by recognizing cancer’s emotional and spiritual toll.

Read more about: Beyond Good Intentions: The 14 Biggest Parenting Mistakes Shaping Your Child’s Future

As we’ve journeyed through the science of charred foods and their potential impact on our cells, it becomes clear that informed choices are our most powerful tool. While the aroma of a grilled meal is undeniably tempting, understanding the nuances of carcinogen formation and individual risk factors empowers us to grill smarter, eat mindfully, and build a stronger foundation for long-term health. Whether through simple cooking adjustments, exploring personalized prevention strategies, or embracing comprehensive and holistic care for those facing a diagnosis, every proactive step taken contributes to a future where we can truly live longer, and live better.