For many, the narrative of the Exodus is synonymous with one towering figure: Moses. He is the divine messenger, the lawgiver, the leader who guided a nascent nation through the wilderness. Yet, to focus solely on Moses is to miss a crucial player, an indispensable partner whose contributions were foundational to the very identity and spiritual future of Israel: Aaron, the elder brother.

Often relegated to a supporting role in popular imagination, Aaron was far more than a mere sidekick. He was an Israelite prophet, a high priest, and a co-leader whose actions, struggles, and triumphs are deeply interwoven into the fabric of biblical history. His story, drawn exclusively from religious texts such as the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and the Quran, demands a closer look, revealing a figure of profound significance.

While Moses was raised in the opulent Egyptian royal court, Aaron and his elder sister Miriam remained rooted with their kinsmen in the northeastern region of the Nile Delta. This divergent upbringing set the stage for their later partnership, with Aaron bringing a unique perspective born from shared experience with their enslaved people.

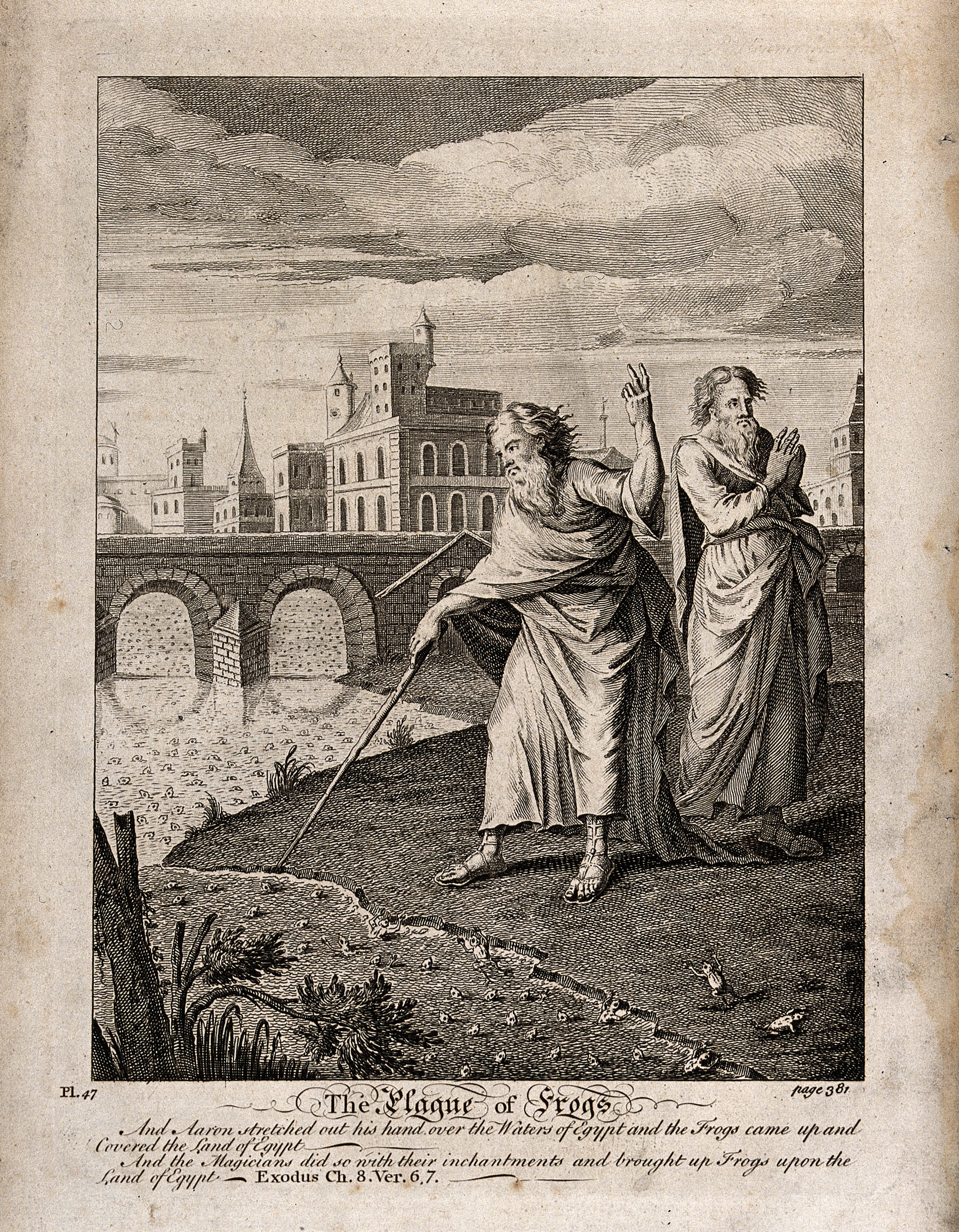

When the momentous confrontation with the Egyptian king became necessary, it was Aaron who stepped into the breach as Moses’ voice. Because Moses himself “complained that he could not speak well,” God appointed Aaron as his “prophet,” serving as the essential spokesman to the Pharaoh.

This early partnership was nothing short of miraculous, quite literally. At Moses’ command, Aaron let his rod turn into a snake, a powerful sign of divine authority. He then stretched out his rod to bring forth the first three plagues, setting in motion the terrifying sequence of events that would ultimately break Pharaoh’s will and secure the Israelites’ liberation.

Though Moses later tended to act and speak for himself, Aaron’s involvement in the wilderness journey remained pivotal. During the fierce battle with Amalek, he was chosen alongside Hur to support Moses’ weary hand as he held the “rod of God” aloft, a symbolic act that determined the tide of conflict.

His leadership continued as the revelation was given to Moses at Mount Sinai. Aaron headed the elders of Israel who accompanied Moses part of the way up the summit, demonstrating his trusted position among the people. While Joshua ascended to the very top with Moses, Aaron and Hur remained below, charged with looking after the vast multitude of Israelites.

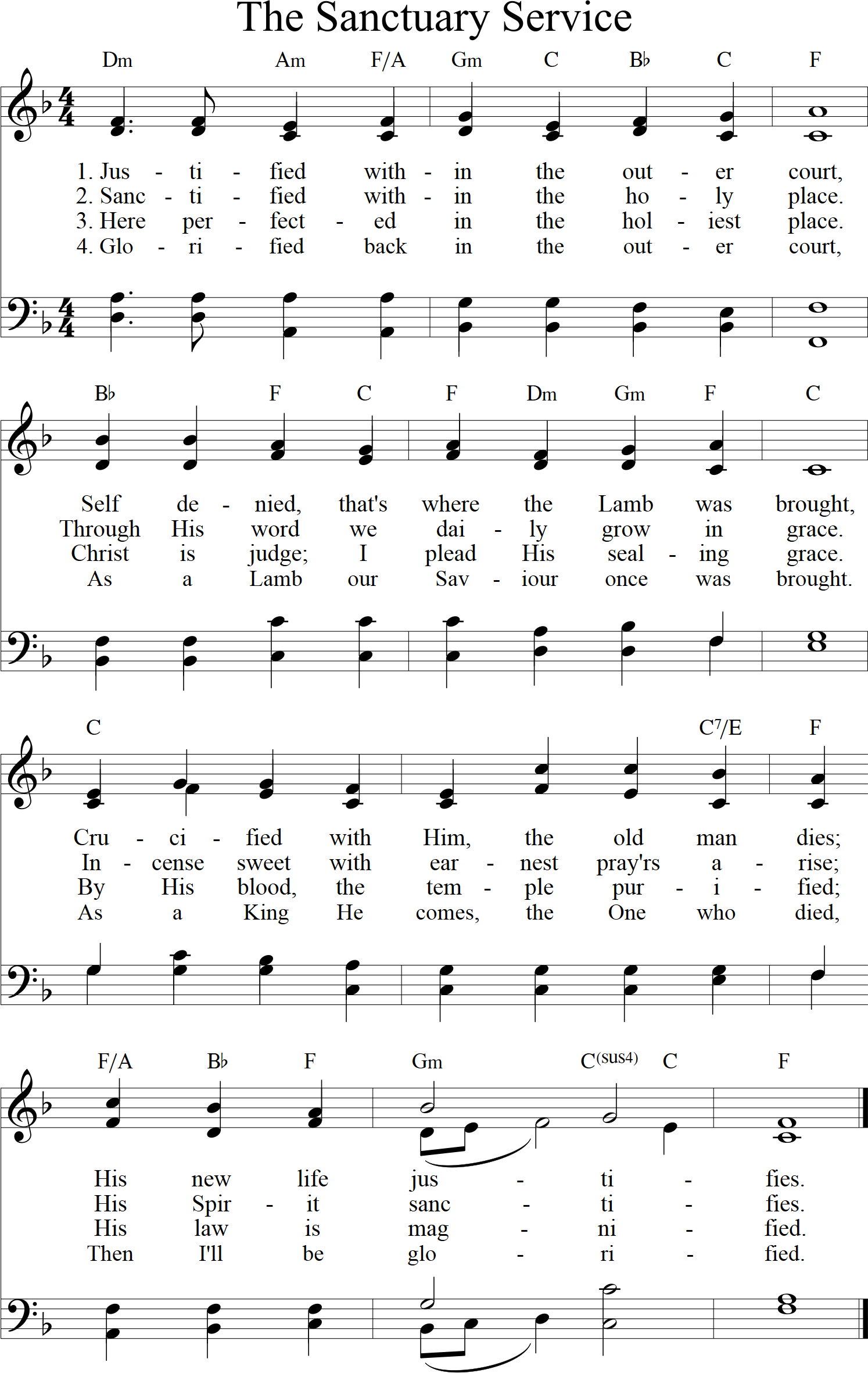

It is at this juncture that Aaron’s role truly transformed. From this point forward in the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, Joshua assumes the mantle of Moses’ direct assistant, while Aaron steps into his predestined role as the first high priest, an office of immeasurable importance for generations to come.

His elevation to the high priesthood was not merely an appointment; it was a divine decree, a covenant. The books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers unequivocally state that Aaron received from God “a monopoly over the priesthood for himself and his male descendants.” This was an exclusive right and profound responsibility: the family of Aaron alone was entrusted to “make offerings on the altar to Yahweh.

The rest of his tribe, the Levites, while consecrated to the service of the sanctuary, were assigned subordinate responsibilities. Moses, acting on divine instruction, anointed and consecrated Aaron and his sons to this sacred office, arraying them in their distinctive robes, thereby establishing a unique and powerful spiritual lineage.

Furthermore, God conveyed “detailed instructions for performing their duties” directly to them, with the rest of the Israelites bearing witness. This included control over the mysterious “Urim and Thummim,” by which the very “will of God could be determined,” solidifying their role as intermediaries between the divine and the human.

Perhaps most significantly, the Aaronide priests were commissioned by God “to distinguish the holy from the common and the clean from the unclean, and to teach the divine laws (the Torah) to the Israelites.” This was a stewardship of unparalleled spiritual education and moral guidance.

Their duties also included the profound act of blessing the people, a ritual that brought divine favor upon the community. The establishment of this sacred institution was dramatically affirmed when Aaron completed the altar offerings for the first time with Moses, and they “blessed the people: and the glory of the LORD appeared unto all the people: And there came a fire out from before the LORD, and consumed upon the altar the burnt offering and the fat [which] when all the people saw, they shouted, and fell on their faces.” This was a clear, unambiguous sign of God’s endorsement.

Yet, despite this dramatic validation, Aaron and his descendants, the Aaronides, appear less frequently in the later historical books of the Hebrew Bible, such as Judges, Samuel, and Kings. Their prominence seems to resurface primarily in literature dating to the Babylonian captivity and thereafter.

The Book of Ezekiel, though focusing heavily on priestly matters, names the priestly upper class as the Zadokites, after one of King David’s priests, and depicts a two-tier priesthood where Levites hold a subordinate position. This structure, with a clear hierarchy of Aaronides and Levites, becomes more pronounced in Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles.

Many historians, in light of these textual patterns, propose that Aaronide families may not have held exclusive control over the priesthood in pre-exilic Israel. What is clear, however, is that “high priests claiming Aaronide descent dominated the Second Temple period.” Most scholars suggest that the Torah reached its final, canonical form early in this period, a fact that may well explain Aaron’s undeniable prominence in the foundational books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers.

Aaron’s journey was not without its trials and tribulations, moments that tested his faith, leadership, and relationship with God and Moses. One of the most infamous incidents occurred during Moses’ prolonged absence on Mount Sinai, a period of immense spiritual tension for the waiting Israelites.

Provoked by the restless people, Aaron was pressed “to make a golden calf.” This grave act of idolatry “nearly caused God to destroy the Israelites.” Moses’ timely and fervent intercession saved the nation, leading the loyal Levites to execute many culprits, with a plague afflicting the survivors.

Remarkably, Aaron himself “escaped punishment for his role in the affair, because of the intercession of Moses according to Deuteronomy 9:20.” Later interpretations, including rabbinic sources and the Quran, often seek to excuse Aaron, depicting him as not the true idol-maker and even as having been mortally threatened by the Israelites upon Moses’ return, begging his pardon.

Another profound tragedy struck on the very day of Aaron’s consecration. His oldest sons, Nadab and Abihu, were consumed by “divine fire because they offered ‘strange’ incense.” This devastating event is interpreted by many as a reflection of conflicts between priestly families in Israel’s past, or simply as a stark warning about the absolute necessity of adhering strictly to God’s instructions given through Moses.

The Torah generally portrays Moses, Aaron, and Miriam as the united leaders of Israel following the Exodus, a harmonious view echoed in the biblical Book of Micah. However, Numbers 12 recounts a rare moment of discord when “Aaron and Miriam complained about Moses’ exclusive claim to be the LORD’s prophet.

Their presumption was swiftly rebuffed by God, who powerfully affirmed Moses’ unique status as the one with whom the LORD spoke “face to face.” Miriam was immediately punished with a skin disease (tzaraath) that turned her skin white. It was Aaron who pleaded with Moses to intercede for her, and Miriam, after seven days of quarantine, was healed. Once again, Aaron escaped direct retribution.

Perhaps the most direct challenge to Aaron’s divinely appointed priesthood came from Korah, a Levite, who, according to Numbers 16–17, led many in directly questioning Aaron’s exclusive claim. When these rebels were dramatically punished by being “swallowed up by the earth,” it was Aaron’s son, Eleazar, who was commanded to handle the censers of the deceased priests.

As a plague erupted among those who had sympathized with the rebels, Aaron, at Moses’ command, took his censer and heroically “stood between the living and the dead until the plague abated,” thereby atoning for the people’s transgression. This act powerfully underscored his indispensable role in averting divine wrath.

To irrevocably emphasize the validity of the Levites’ claim to the offerings and tithes, Moses collected a rod from the leader of each tribe and laid them overnight in the tent of meeting. The next morning, Aaron’s rod alone was found to have miraculously “budded and blossomed and produced ripe almonds.” This clear divine sign was then placed before the Ark of the Covenant, forever symbolizing Aaron’s unparalleled right to the priesthood. The following chapter further clarified the distinct roles: all Levites were consecrated to the sanctuary’s care, but “charge of its interior and the altar was committed to the Aaronites alone.”

Like Moses, Aaron was not permitted to enter Canaan with the Israelites. This divine judgment came after an incident where, commanded to speak to a rock to bring forth water, Moses struck it twice instead, a display construed as “a lack of deference to the LORD.” It was a poignant end to a shared journey, just shy of the promised land.

The Torah provides two distinct accounts of Aaron’s death. Numbers states that shortly after the Meribah incident, Aaron, accompanied by Moses and his son Eleazar, ascended Mount Hor. There, Moses solemnly stripped Aaron of his priestly garments, transferring them to Eleazar, signifying the continuation of the priesthood through his lineage. Aaron then died on the summit, at the age of 123, and the people mourned him for a full thirty days.

Deuteronomy 10:6, however, places these events at Moseroth. This geographical discrepancy is notable, as “the itinerary in Numbers 33:31–37 records seven stages between Moseroth (Mosera) and Mount Hor.” Aaron’s passing is recorded as occurring on the 1st of Av, marking the close of an extraordinary life of service.

Aaron’s legacy was secured through his descendants. He married Elisheba, the daughter of Amminadab and sister of Nahshon from the tribe of Judah. Their sons were Nadab, Abihu, Eleazar, and Ithamar; notably, only Eleazar and Ithamar had progeny, continuing the sacred lineage.

Any descendant of Aaron is known as an Aaronite, or Kohen, meaning Priest, establishing a direct, patrilineal line of hereditary priesthood. Non-Aaronic Levites, those descended from Levi but not from Aaron, were responsible for assisting the Aaronite priests in the sacred duties of the tabernacle, and later, the temple.

His importance resonates even into the New Testament, where the Gospel of Luke records that both Zechariah and Elizabeth, and by extension their son John the Baptist, were direct descendants of Aaron, linking the past priestly line to the harbinger of the Messiah.

Scholarly discourse, particularly the arguments of Thomas Römer, suggests that the Pentateuch, in its final form, reflects “unresolved tensions” among three distinct groups: a lay group aligned with Moses, a priestly group linked to Aaron, and the Levites. These internal dynamics, particularly during the Persian and early Hellenistic periods, shaped how their roles were ultimately presented.

Römer posits that compromises are evident, especially in texts like Exodus and Leviticus, where Moses and Aaron often collaborate, though Moses consistently remains dominant. Despite this collaboration, disagreements persisted, with some texts emphasizing Moses’s undeniable superiority while others worked to elevate Aaron’s status. The Pentateuch, in its canonical wisdom, ultimately preserves these complex, sometimes conflicting narratives, portraying Moses as the unparalleled mediator of the Torah, but never erasing Aaron’s pivotal, divinely appointed role.

Across the diverse tapestry of Abrahamic faiths, Aaron stands as a figure of enduring reverence and interpretation. In Jewish rabbinic literature, a fascinating evolution of his portrayal unfolds.

Older prophetic writers, who viewed priests as representing a religious form inferior to prophetic truth, often placed Aaron below Moses, seeing him primarily as Moses’ mouthpiece and an executor of God’s will. These traditions suggested Aaron lacked the willpower to fully resist the multitude’s “idolatrous proclivities,” particularly regarding the golden calf, although even here, later rabbis would find “extenuating circumstances for Aaron.”

However, under the significant influence of the priesthood that heavily shaped the nation’s destiny during Persian rule, a different, more elevated ideal of the priest emerged. This period saw a powerful tendency to place “Aaron on a footing equal with Moses.” As the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael strongly implies, “At times Aaron, and at other times Moses, is mentioned first in Scripture—this is to show that they were of equal rank.”

Rabbinic narratives vividly describe Aaron’s death as being of “a wonderful tranquility,” a fulfillment of the promise of peaceful life symbolized by the anointing oil. Accompanied by Moses and Eleazar, Aaron ascended Mount Hor, where a beautiful, lamp-lit cave miraculously opened before him.

Moses instructed him to transfer his priestly raiment to Eleazar, then invited him into the cave to lie upon a prepared bed surrounded by angels. Aaron “obeyed without a murmur,” and his soul departed “as if by a kiss from God.” The cave then closed, and Moses, returning with Eleazar, cried, “Alas, Aaron, my brother! thou, the pillar of supplication of Israel!”

When the Israelites, bewildered, questioned Aaron’s disappearance, angels were seen carrying his bier through the air. A voice from heaven proclaimed: “The law of truth was in his mouth, and iniquity was not found on his lips: he walked with me in righteousness, and brought many back from sin.” His passing on the first of Av was so momentous that “the pillar of cloud which proceeded in front of Israel’s camp disappeared at Aaron’s death,” a testament to his vital protective role.

The seeming contradiction between the Mount Hor and Mosera accounts of his death is ingeniously resolved by the rabbis: Aaron died on Mount Hor, but the subsequent defeat of the people led them to flee seven stations back to Mosera, where they performed the rites of mourning for him. Thus, “There [at Mosera] died Aaron” refers to the place of mourning, not necessarily the exact point of death.

The rabbis particularly praise the profound “brotherly sentiment between Aaron and Moses.” Far from jealousy, “neither betrayed any jealousy; instead, they rejoiced in each other’s greatness.” When Moses initially hesitated to go to Pharaoh, fearing he would deprive Aaron of his long-held position, God reassured him that Aaron “will be glad in his heart.”

Indeed, Aaron’s heart, which “had leaped with joy over his younger brother’s rise to glory greater than his,” was divinely rewarded by being “decorated with the Urim and Thummim,” which were to “be upon Aaron’s heart when he goeth in before the Lord.” Their joyful meeting, characterized by true brotherly embraces, inspired the verse: “Behold how good and how pleasant [it is] for brethren to dwell together in unity!”

Their complementary roles are beautifully captured by the saying: “Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed [each other]”; for Moses “stood for righteousness” and Aaron for “peace.” Aaron personified mercy, while Moses represented truth.

Even when Moses poured the anointing oil upon Aaron’s head, Aaron’s humility shone through. He modestly recoiled, expressing concern that he might have somehow blemished the sacred oil. However, the Shekhinah, the divine presence, intervened, confirming the oil’s purity, likening it to the precious ointment running down Aaron’s beard, as pure as “the dew of Hermon.”

According to the Tanhuma, a collection of rabbinic teachings, Aaron’s prophetic activity actually “began earlier than that of Moses.” The sage Hillel held Aaron up as a supreme example, famously saying: “Be of the disciples of Aaron, loving peace and pursuing peace; love your fellow creatures and draw them nigh unto the Law!” This speaks volumes about his character.

Tradition further illustrates Aaron as an “ideal priest of the people,” who was “far more beloved for his kindly ways than was Moses.” While Moses was often portrayed as stern and uncompromising, Aaron moved through the community as a gentle “peacemaker,” actively “reconciling man and wife when he saw them estranged, or a man with his neighbor when they quarreled, and winning evil-doers back into the right way by his friendly intercourse.

Crucially, the Quran “additionally denies the role of Aaron in the creation of the golden calf, attributing the action to Samiri,” thus absolving him of this grave transgression. His primary importance in Islam lies in his vital role alongside his younger brother, Musa (Moses), in preaching to the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

Beyond his direct assistance to Moses, Islamic tradition also accords Aaron the significant role of a patriarch, as it records that the priestly descent passed through his lineage, encompassing “the entire House of Amran,” a testament to his profound generational impact.

In the Baháʼí Faith, Aaron is described as a prophet, distinct from an apostle, with the Kitáb-i-Íqán identifying Imran as his father, further integrating him into the broader lineage of Abrahamic prophets and spiritual figures.

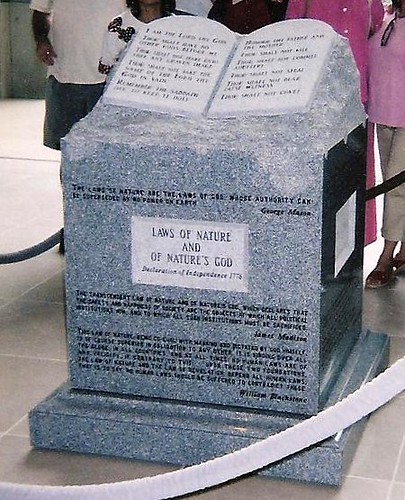

Aaron’s enduring presence is vividly captured in art, where he frequently appears paired with Moses in both Jewish and Christian works, especially in manuscript illustrations and printed Bibles. His visual identity is distinct, typically marked by his elaborate “priestly vestments, especially his turban or miter and jeweled breastplate.” He often holds a censer, symbolizing his priestly functions, or his miraculous flowering rod.

His depiction extends to scenes portraying the wilderness Tabernacle and its altar, such as the third-century frescos in the synagogue at Dura-Europos in Syria. An eleventh-century portable silver altar from Fulda, Germany, housed in the Musée de Cluny in Paris, also features Aaron with his censer.

He is a common sight in the frontispieces of early printed Passover Haggadot and occasionally in church sculptures. While rarely the singular subject of portraits, he has been captured by artists like Anton Kern and Pier Francesco Mola. Christian artists sometimes portray him as a prophet, holding a scroll, as seen in a twelfth-century sculpture from the Cathedral of Noyon.

Illustrations of the Golden Calf story invariably include him, most notably in Nicolas Poussin’s iconic “The Adoration of the Golden Calf.” The significant act of his ordination, alongside his sons, as detailed in Leviticus 8, has also been a subject for artists, with Harry Anderson’s realistic portrayal frequently reproduced in Latter Day Saint literature.

His story has also reached the silver screen, with Aaron depicted in Exodus-related dramas such as the classic “The Ten Commandments” (1956) and “Exodus: Gods and Kings” (2014), bringing his ancient narrative to modern audiences. These portrayals, while varying in historical fidelity, underscore his indelible place in the grand Exodus narrative.

From his humble beginnings in the Nile Delta to his pivotal role as Moses’ spokesman, and ultimately, as Israel’s first High Priest, Aaron’s journey is a testament to divine calling and human partnership. He navigated complex challenges, from the golden calf to family strife and rebellions, always ultimately affirming his unique, consecrated position. His spiritual lineage laid the foundation for Israel’s worship and identity for centuries, echoing through diverse faith traditions to this day.

Aaron’s story reminds us that even in the shadow of giants, invaluable contributions are made, and legacies are forged. His life was not just a historical footnote but a dynamic force that shaped the spiritual landscape, a ‘pillar of supplication’ whose influence, like the eternal lamp he was commanded to kindle, continues to burn brightly, illuminating the path for countless generations. Truly, his was a game-changing impact on the history of faith.