The Mediterranean Sea, often called the cradle of civilization, is far more than just a body of water separating continents. It’s a vibrant, living tapestry woven with threads of deep history, intricate geography, and profound human narratives that have shaped the world as we know it. From ancient empires that vied for its control to the crucial trade routes that crisscrossed its expanse, this sea has been the beating heart of countless developments.

Its unique position, nearly entirely enclosed by Europe, Africa, and Asia, has made it a nexus for cultural exchange, economic prosperity, and, at times, conflict. Understanding the Mediterranean is to understand the very origins and evolution of many modern societies. Its mild winters and warm summers define a climate type that has nurtured diverse civilizations along its extensive shorelines, yet it remains a dynamic and ever-changing environment.

Join us on an incredible journey to uncover the multifaceted story of the Mediterranean Sea, exploring its foundational characteristics and the pivotal moments that have marked its long and illustrious past. We’ll delve into the fascinating geographical features that define it, peer into its ancient geological secrets, and trace the rise and fall of powers that sought to call it “Our Sea.”

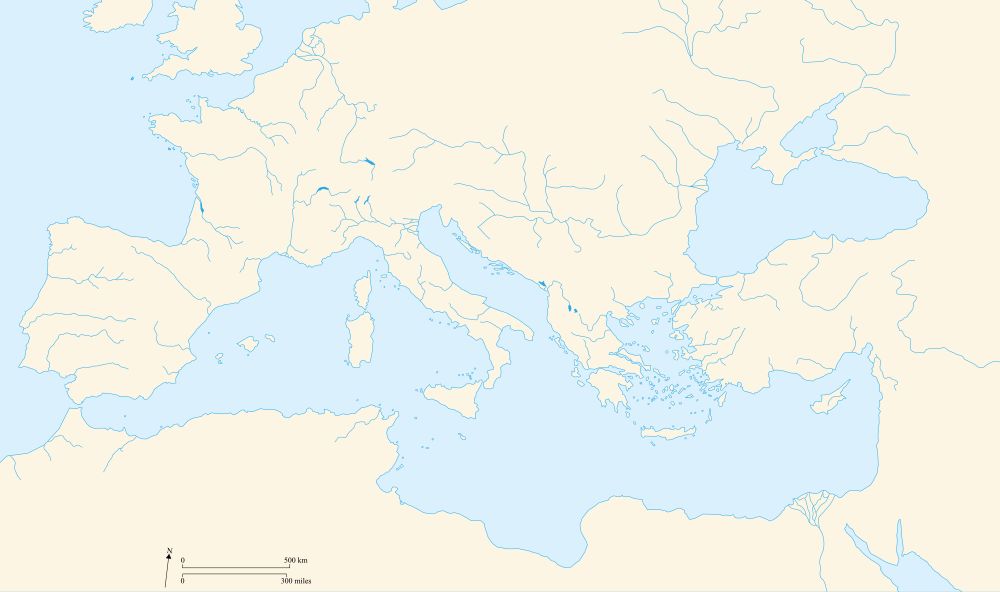

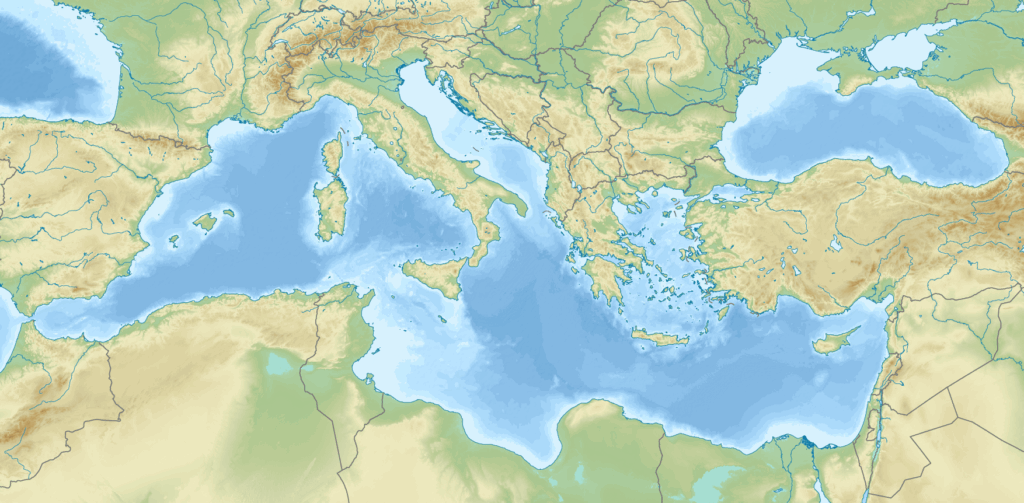

1. **Geographical Overview: Where the Continents Meet**: The Mediterranean Sea, known as MED-ih-tə-RAY-nee-ən, is an expansive body of water connected to the Atlantic Ocean. It is almost completely enclosed by land, bounded on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the west nearly by the Morocco–Spain border. This unique geographic embrace gives it its distinctive character as an “internal sea.”

Spanning an impressive area of approximately 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi), the Mediterranean represents a mere 0.7% of the global ocean surface. Its primary connection to the vast Atlantic is through the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, a mere 14 km (9 mi) wide, which famously separates the Iberian Peninsula in Europe from Morocco in Africa. This slender link is vital, as it governs the sea’s interaction with the wider ocean.

The sea also boasts a significant average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft), with its deepest recorded point plummeting to 5,109 ± 1 m (16,762 ± 3 ft) in the Calypso Deep within the Ionian Sea. Its west–east length, stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of Alexandretta on Turkey’s southeastern coast, measures about 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi). The north–south length, however, varies considerably depending on the specific shorelines and routes considered, highlighting its complex and irregular shape.

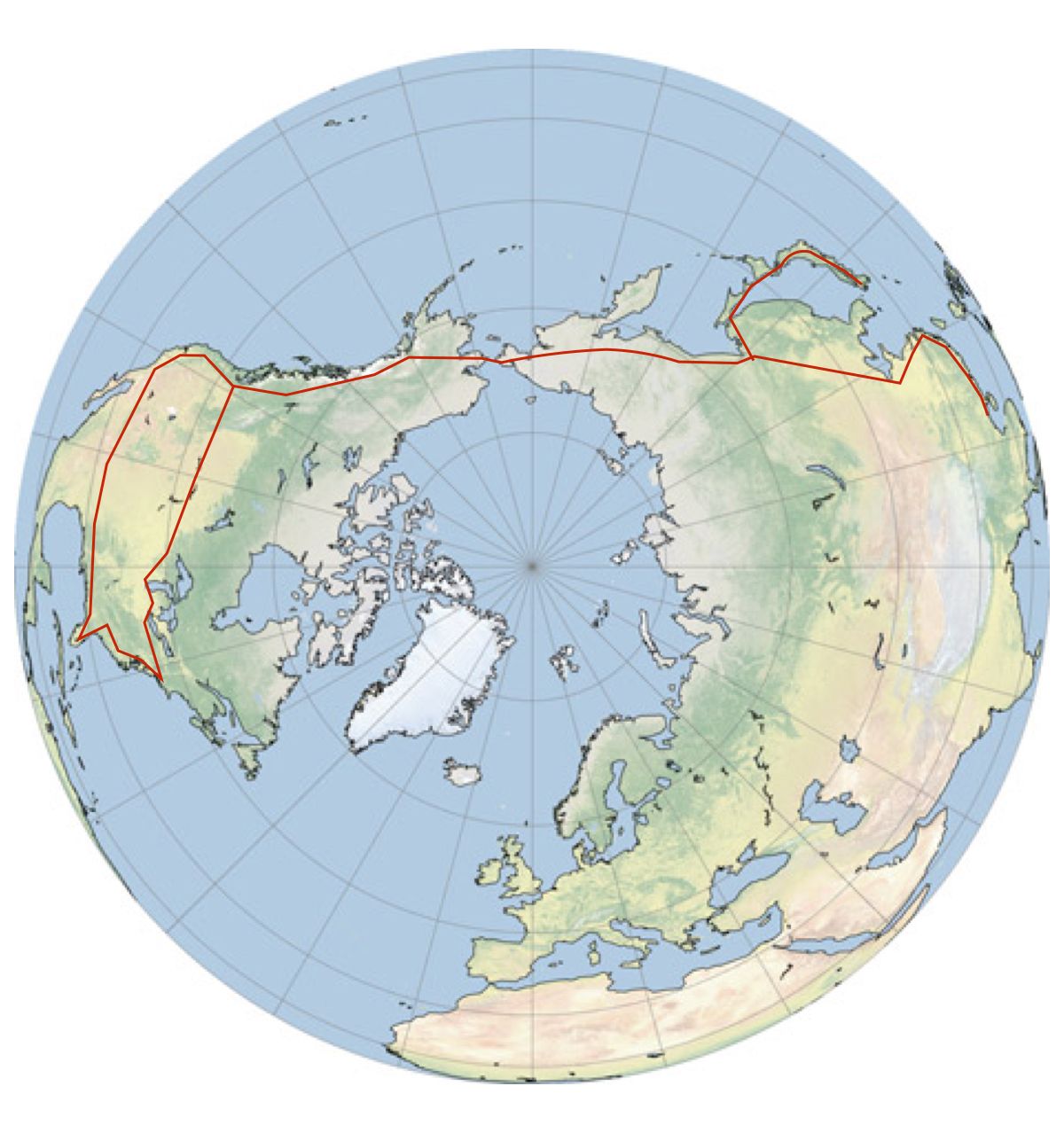

2. **A Storied Past: The Messinian Salinity Crisis**: Beneath the Mediterranean’s shimmering surface lies a dramatic geological history, perhaps none more compelling than the Messinian Salinity Crisis. Geological evidence reveals that around 5.9 million years ago, this vast sea was entirely cut off from the Atlantic Ocean, leading to a period of partial or complete desiccation. This incredible event unfolded over some 600,000 years, transforming the sea into a vast, arid desert blanketed with evaporite salts.

During this crisis, the seafloor was not necessarily entirely dry as once believed. More recent seismic and microfossil research suggests that around 5 million years ago, it comprised numerous basins of varying topography and sizes, with depths ranging from 200 to 1,520 metres (650 to 5,000 ft). Salts likely accumulated at the bottom of these highly salinized waters, adding layers of complexity to this ancient geological puzzle.

The monumental refilling of the Mediterranean occurred approximately 5.3 million years ago, an event known as the Zanclean flood. This catastrophic inundation saw Atlantic waters breaking through the high ridges of Gibraltar, rapidly re-establishing the sea. The uncertainty surrounding the precise timing and nature of this sea-bottom salt formation, as well as the details of the refilling, continues to be a subject of intense scientific debate, making it a fascinating area of ongoing research.

3. **Cradle of Civilizations: Ancient Trade and Cultural Exchange**: From its earliest days, the Mediterranean Sea served as an indispensable artery for merchants and travelers, fostering an unparalleled degree of trade and cultural exchange among the diverse peoples inhabiting its region. The history of the Mediterranean is, in essence, crucial to understanding the genesis and development of many of our modern societies. It was not merely a boundary but a bridge.

Major ancient civilizations flourished around its shores, utilizing the sea for commerce, colonization, and even warfare. It provided not just routes for interaction but also vital sustenance through fishing and the gathering of other seafood for countless communities throughout the ages. Among the earliest advanced civilizations to emerge were the Egyptians and the Minoans, who engaged in extensive reciprocal trade, laying foundations for sophisticated maritime networks.

Around 1200 BC, the eastern Mediterranean experienced a profound upheaval known as the Bronze Age Collapse, which led to the widespread destruction of many cities and the disruption of established trade routes. Yet, the sea’s importance persisted, with other notable classical antiquity civilizations like the Greek city-states and Phoenicians extensively colonizing its coastlines, demonstrating its enduring role as a lifeline for burgeoning societies.

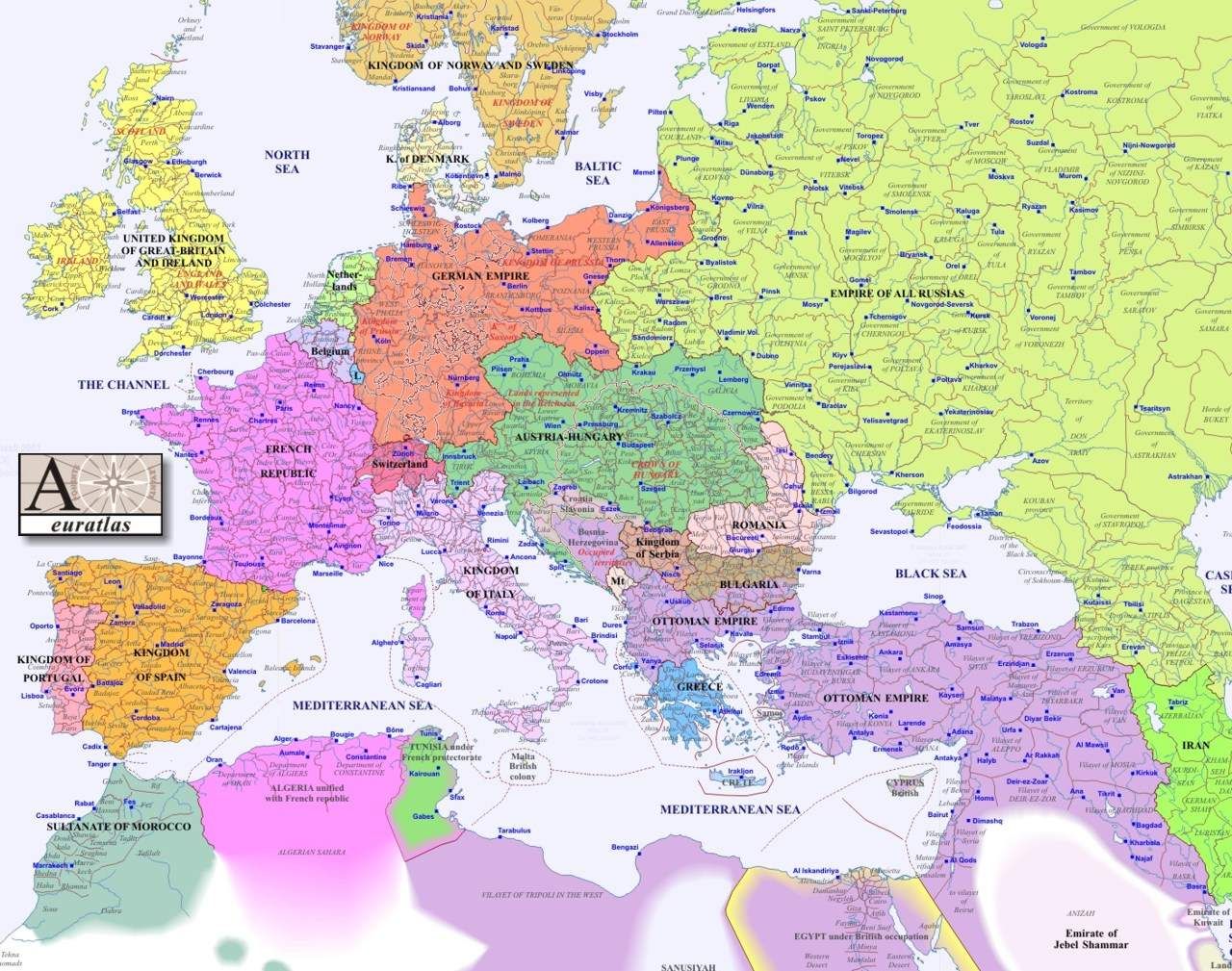

4. **Mare Nostrum: The Roman Empire’s Unrivaled Control**: Following the pivotal Punic Wars in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, the Roman Republic emerged victorious over the Carthaginians, securing its position as the preeminent power in the Western Mediterranean. This ascendancy marked a new era for the sea, one of unprecedented control and influence. When Augustus established the Roman Empire, the Romans proudly referred to the Mediterranean as “Mare Nostrum,” meaning “Our Sea.”

For the subsequent 400 years, the Roman Empire maintained an astonishing nautical hegemony, completely controlling the Mediterranean Sea and virtually all its coastal regions. This dominion stretched from Gibraltar in the west all the way to the Levant in the east, earning the sea the popular nickname “Roman Lake.” No other state has ever achieved such complete command over all its coasts, underscoring the formidable power of the Roman Empire.

This era of Roman control facilitated immense stability and prosperity across the region, allowing for the unhindered movement of goods, people, and ideas. The sea became a conduit for unification, solidifying Rome’s vast imperial reach. Darius I of Persia, who had conquered Ancient Egypt even before this Roman dominance, also recognized the strategic value of such maritime connections by building a canal linking the Red Sea to the Nile, and thus to the Mediterranean.

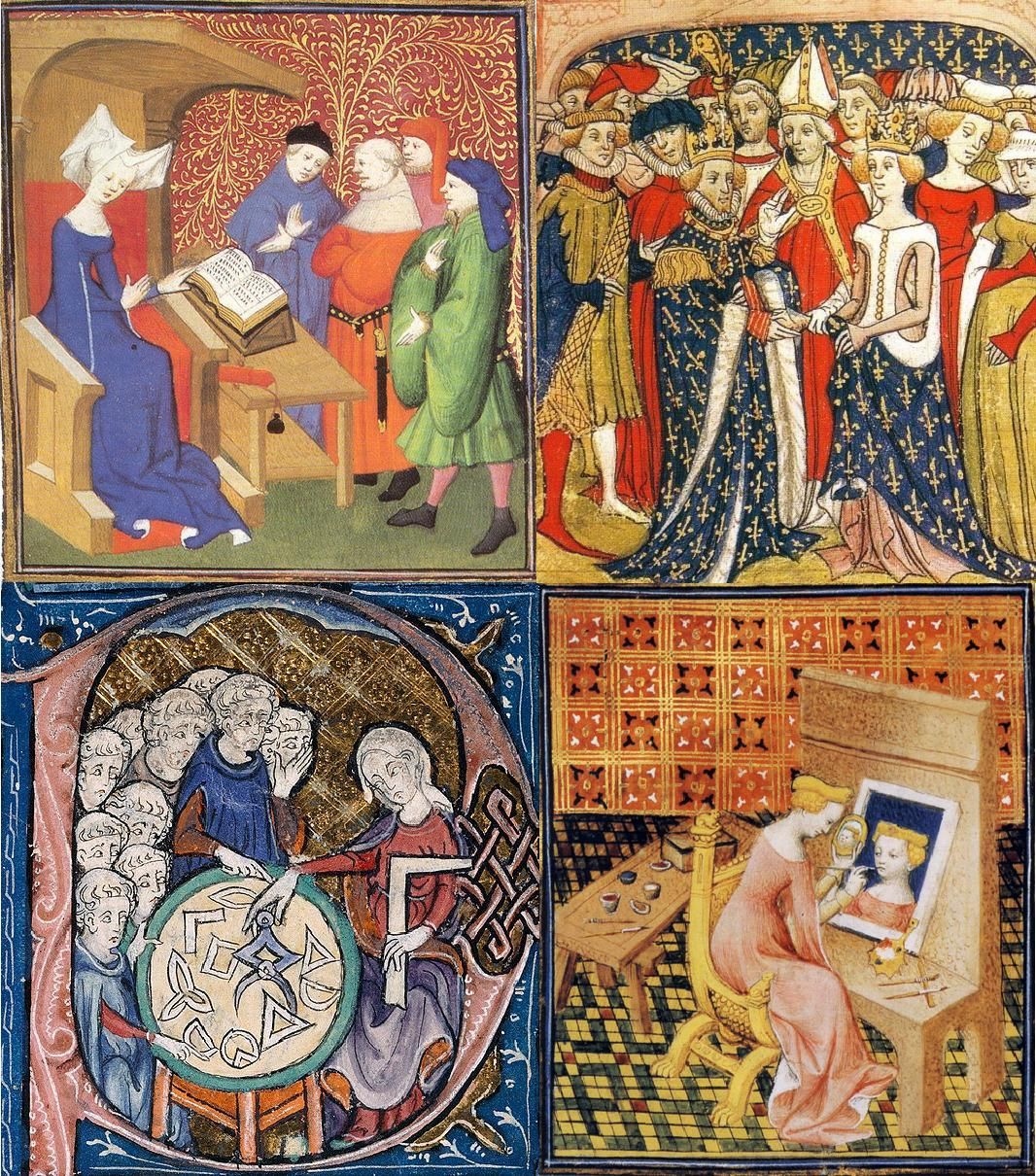

5. **The Flourishing Middle Ages: Arab Influence and Trade Revitalization**: The collapse of the Western Roman Empire around 476 AD ushered in a new chapter for the Mediterranean. While Roman power persisted in the Byzantine Empire in the east, the 7th century saw the dramatic rise of Islam, whose influence soon swept across the region from the east. At its greatest extent, the Arabs, under the Umayyads, controlled the Iberian Peninsula, bringing a new phase of art and culture to the Mediterranean world.

This period of Arab rule was particularly transformative for the western Mediterranean, especially Spain and Sicily. Through the extensive commercial networks of the Islamic world, a variety of foodstuffs, spices, and crops were introduced. These included valuable commodities such as sugarcane, rice, cotton, alfalfa, oranges, lemons, apricots, spinach, eggplants, carrots, saffron, and bananas. The Arabs also meticulously continued the widespread cultivation and production of olive oil, a staple from classical Greco-Roman times, with the Spanish words for ‘oil’ and ‘olive’ (aceite and aceituna) deriving from the Arabic al-zait, meaning ‘olive juice.’ Pomegranates, the heraldic symbol of Granada, also flourished under their care.

While the Arab invasions initially disrupted trade relations between Western and Eastern Europe and routes with Eastern Asian Empires, they also indirectly promoted new trade across the Caspian Sea. Products like silk and spices from East Asian empires were re-routed through Egypt to ports like Venice and Constantinople. Despite Viking raids further disrupting Western European trade, the Norsemen concurrently developed trade from Norway to the White Sea and engaged in luxury goods exchange with Spain and the Mediterranean. By the mid-8th century, the Byzantines re-established control over the northeastern Mediterranean. Venetian ships, by the 9th century, began arming themselves to counter Arab harassment, focusing their trade on Asian goods in Venice, signaling the sea’s continuous, evolving commercial significance.

6. **Shifting Tides of Power: Ottoman Empire and European Naval Might**: As the Middle Ages progressed, new powers rose and vied for supremacy across the Mediterranean. The Fatimids, for example, maintained robust trade relations with Italian city-states like Amalfi and Genoa even before the Crusades, as evidenced by Cairo Geniza documents. Letters from this period mention Amalfian merchants residing in Cairo and Genoese traders engaging with Alexandria, highlighting a complex web of economic ties.

The Crusades, while religious conflicts, inadvertently led to a significant flourishing of trade between Europe and the outremer region. Italian maritime republics like Genoa, Venice, and Pisa capitalized on this, establishing colonies in Crusader-controlled areas and gaining considerable control over trade with the Orient. Even after the fall of the Crusader states and papal attempts to ban trade with Muslim states, the commerce persisted, reflecting the irresistible pull of Mediterranean trade. Europe itself began a gradual revival and centralization of state power during the Renaissance of the 12th century, setting the stage for future confrontations.

However, a dominant force from Anatolia, the Ottoman Empire, continued its expansion. In 1453, they extinguished the Byzantine Empire with the conquest of Constantinople, solidifying their power. Hayreddin Barbarossa, a formidable Ottoman captain, symbolized this ascendancy with the victory at the Battle of Preveza in 1538, which effectively opened Tripoli and the eastern Mediterranean to Ottoman rule. Yet, as European naval prowess grew, they eventually confronted Ottoman expansion, culminating in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. This decisive victory for the European Holy League against the Ottomans severely damaged the Ottoman Navy and marked the last major naval battle fought primarily between galleys, signaling a profound shift in maritime warfare and power dynamics.

7. **The Age of Global Trade: From Galleys to Oceanic Routes**: For centuries, the Mediterranean Sea was the primary conduit for trade between Western Europe and the East, a bustling thoroughfare for silks, spices, and countless other valuable goods. However, a profound transformation began after the 1490s with the development of a direct sea route to the Indian Ocean. This groundbreaking innovation allowed for the importation of Asian spices and other commodities directly through the Atlantic ports of Western Europe, fundamentally altering traditional trade flows and diminishing the Mediterranean’s monopolistic role.

Despite this shift in global trade routes, the Mediterranean remarkably retained its strategic importance, demonstrating its enduring geopolitical value. British mastery of Gibraltar, for instance, ensured their significant influence in both Africa and Southwest Asia. Critical naval battles, such as Abukir in 1799 (the Battle of the Nile) and Trafalgar in 1805, further solidified British dominance in the Mediterranean for a considerable period, underscoring the sea’s continued relevance in imperial ambitions.

The 20th century saw the Mediterranean become a crucial theater in both World War I and World War II, as well as the focal point of the Suez Crisis and Cold War dynamics. A momentous change occurred with the opening of the lockless Suez Canal in 1869, which revolutionized trade between Europe and Asia. This artificial waterway established the fastest route through the Mediterranean to East Africa and Asia, leading to a rapid economic rise for Mediterranean countries and their ports, such as Trieste, which gained direct connections to Central and Eastern Europe. While trade routes shifted temporarily to European northern ports during the World Wars and the Cold War, European integration, the activation of the Silk Road, and free world trade later steered commercial traffic back towards the southern ports, ensuring the Mediterranean’s continued, albeit evolving, centrality in global commerce.

8. **Diverse Sub-regions: The Marginal Seas**The Mediterranean isn’t just one vast expanse; it’s a mosaic of smaller, distinct water bodies, each with its own unique character and surrounding nations. These ‘marginal seas’ play a crucial role in the region’s diverse ecosystems and human interactions, reflecting the complex interplay of geography and culture that defines the broader Mediterranean basin. The International Hydrographic Organization recognizes 15 such marginal seas, each contributing to the Mediterranean’s intricate identity.

Among these, we find the expansive Libyan Sea, stretching across Libya, Greece, Malta, and Italy, and the Levantine Sea to the east, bordered by Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, and the island nation of Cyprus. Further north, the Aegean Sea, which itself includes the Icarian, Myrtoan, and Thracian Seas, intricately weaves through Greece and Turkey, dotted with countless islands. Each of these subdivisions, though part of the greater Mediterranean, possesses distinct hydrographic and climatic features, creating a tapestry of marine environments.

Moving west, the Ionian Sea deepens between Greece, Albania, and Italy, holding the Mediterranean’s deepest point, the Calypso Deep. The Adriatic Sea, elongated and embraced by Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Italy, Montenegro, and Slovenia, is known for its myriad islands and unique coastal landscapes. Further west, the Balearic Sea abuts Spain, while the Tyrrhenian Sea, enclosed by Sardinia, Corsica, the Italian peninsula, and Sicily, and the Ligurian Sea between Corsica and Liguria, complete this fascinating geographical breakdown, showcasing the sea’s remarkable internal diversity.

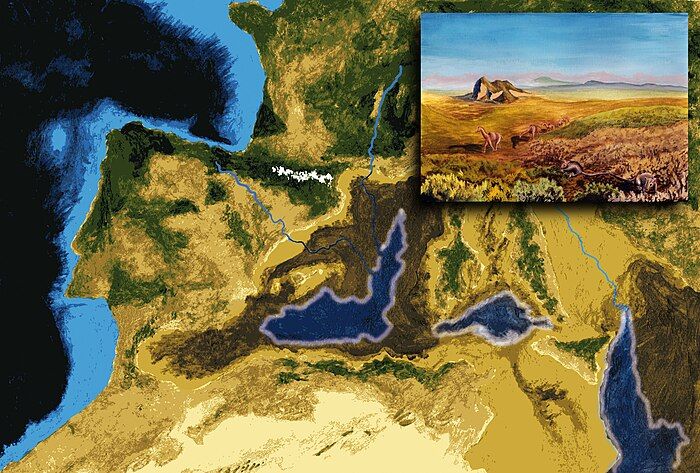

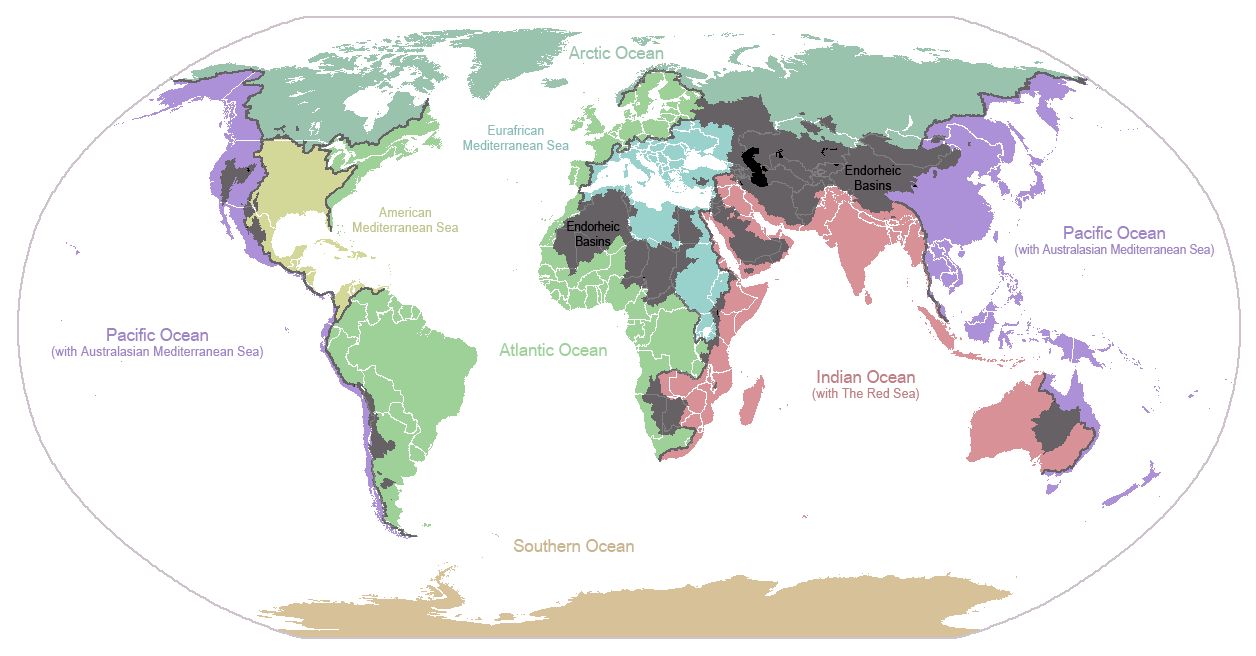

9. **The Extensive Drainage Basin: A Lifeline Across Continents**Beyond its immediate coastline, the Mediterranean Sea draws its lifeblood from an enormous and incredibly varied drainage basin, stretching across vast swathes of Europe, Africa, and Asia. This basin, estimated to encompass between 4,000,000 and 5,500,000 square kilometers, highlights the sea’s profound connection to distant lands and diverse ecosystems. It’s a geographical marvel where rivers originating far inland eventually converge, carrying vital freshwater and sediment into the Mediterranean.

The mighty Nile River, taking its sources in equatorial Africa and encompassing approximately two-thirds of the Mediterranean drainage basin, stands as the longest river to empty into the sea, its historical floods shaping ancient civilizations. In Europe, significant contributors include the Rhône, Ebro, Po, and Maritsa rivers, with the Rhône’s basin extending north into the Jura Mountains, even crossing the Alps. These European rivers, particularly the Rhône and Po, discharge volumes similar to the Nile, emphasizing the significant rainfall in the European part of the basin, especially near the Alps, often called the ‘water tower of Europe.’

Interestingly, the Mediterranean’s drainage basin extends far beyond its coastal countries. Nations such as Andorra, Bulgaria, Kosovo, North Macedonia, San Marino, Serbia, and Switzerland in Europe, and Congo, Burundi, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda in Africa, all contribute to the sea’s waters through their river systems. This vast network underscores how the health and flow of the Mediterranean are intrinsically linked to the environmental practices and climatic patterns across multiple continents, making it a truly interconnected body of water.

10. **Myriad Islands: Jewels of the Mediterranean**The shimmering expanse of the Mediterranean Sea is not just open water; it’s adorned with an astonishing array of islands and islets, numbering around 10,000 in total. These island jewels, with approximately 250 of them permanently inhabited, represent unique microcosms of culture, history, and biodiversity, each telling its own compelling story within the grand narrative of the sea. They have served as crucial stepping stones for trade, strategic outposts for empires, and cherished homes for generations.

Among this multitude, some stand out for their sheer size and population, acting as major hubs within the basin. Sicily, belonging to Italy, claims the title of the largest, followed closely by Sardinia, also Italian, both boasting significant land areas and vibrant populations. The island nation of Cyprus, situated in the eastern Mediterranean, is another major landmass, while Mallorca in Spain, Crete and Euboea in Greece, and Corsica in France, are also among the largest, each contributing distinctive landscapes, traditions, and economic activities to the Mediterranean tapestry.

These islands, some of volcanic origin, are not merely geographical features but living entities that shape and are shaped by the sea around them. From the ancient ruins dotting Crete to the picturesque beaches of Mallorca, and the rugged mountains of Corsica to the strategic position of Cyprus, they are integral to the Mediterranean’s identity. They offer glimpses into diverse cultures, unique ecosystems, and the enduring human connection to this remarkable sea, making island hopping an essential part of understanding the region.

11. **Unique Climate Patterns and Sea Temperatures**The Mediterranean region is globally renowned for its distinctive climate, which has lent its name to a climate type characterized by specific seasonal patterns. This ‘hot-summer Mediterranean climate’ typically features mild, wet winters and, in stark contrast, calm, dry, and often intensely hot summers. The majority of the annual precipitation conveniently falls during the cooler months, providing crucial water resources during the less evaporative periods.

While generally temperate, the Mediterranean Sea is not entirely immune to extreme weather phenomena. Though rare, tropical cyclones can occasionally form within its basin, typically occurring in the late autumn months, specifically between September and November. These events, though less frequent and often less intense than their oceanic counterparts, serve as a reminder of the dynamic nature of the sea’s climatic system and its susceptibility to atmospheric shifts.

The sea’s water temperatures generally mirror the air temperatures, contributing to its pleasant, hospitable environment for both marine life and human activity. For instance, surface temperatures in cities like Malaga range from around 15-16°C (59-61°F) in winter to a warm 22-23°C (72-73°F) in summer, with some eastern locations like Tel Aviv and Mersin reaching up to 28-29°C (82-84°F) in August. This mild and warm water, combined with the distinctive climate, has fostered rich biodiversity and attracted human settlement for millennia, shaping the lifestyles and agricultural practices of coastal communities.

Read more about: Beyond the Coasts: Why Four Dynamic Sunbelt Cities Are Redefining America’s Economic Future

12. **Complex Underwater Geology: A Dynamic Seabed**Beneath the Mediterranean’s inviting surface lies a complex and dynamic geological landscape, profoundly shaped by the relentless movements of the Earth’s tectonic plates. The subduction of the African Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate is the primary architect of the sea’s underwater features, creating a diverse and often dramatic topography. This ongoing geological activity has divided the sea into distinct regions, most notably into western and eastern basins, separated by significant underwater structures.

A key feature separating these basins is the Malta Escarpment, a formidable 250-kilometer undersea limestone cliff stretching south from Sicily’s eastern coast towards the Maltese islands. This escarpment, formed by tectonic activity, boasts canyons that can plummet up to 3.5 kilometers, revealing ancient geological processes. These deep valleys, uncarved by surface rivers, are unique and serve as conduits for underwater currents carrying contaminants and nutrients, supporting rich biological communities, while also posing natural hazards like landslides.

The western Mediterranean basin is further subdivided into three main underwater basins: the Alboran Basin (acting as a gateway to the Atlantic and a biodiversity hotspot), the Algerian Basin (stretching to the French coast with depths up to 2,800 meters, known for hydrocarbon exploration), and the Tyrrhenian Basin, home to significant undersea volcanoes like Marsili and Palinuro Seamount, which are among Europe’s largest. Similarly, the eastern Mediterranean basin includes the Ionian Basin (containing the Calypso Deep, the Mediterranean’s deepest point), the Levantine Basin (separated by the Mediterranean Ridge, known for mud volcanoes and the Eratosthenes Seamount), the Aegean Sea (north of Crete), and the Adriatic Sea. This intricate underwater geology continues to be a subject of intense scientific study, revealing secrets about the Earth’s ancient past and ongoing transformations.

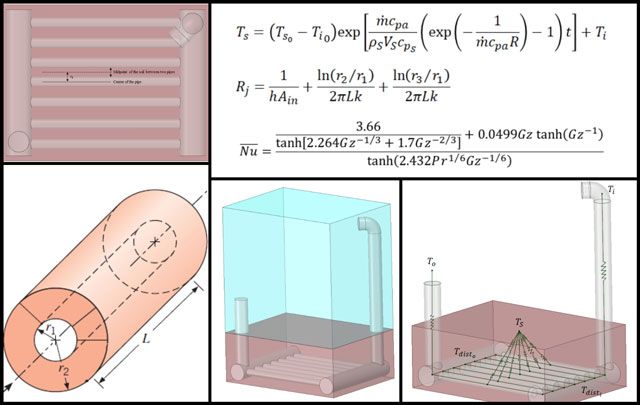

13. **Oceanography: The Intricate Dance of Water Circulation**The Mediterranean Sea’s unique oceanography is governed by a fascinating interplay of evaporation, precipitation, and its connections to larger ocean bodies. A defining characteristic is that evaporation significantly outweighs both precipitation and river runoff, leading to a net water deficit within the basin. This deficit is particularly pronounced in the eastern half, resulting in gradually increasing salinity and decreasing water levels as one moves eastward. The average salinity across the basin is approximately 38 PSU at a depth of 5 meters, showcasing its relatively high salt content.

To compensate for this constant loss of water, there is a crucial net influx of water from the Atlantic Ocean through the narrow Strait of Gibraltar, amounting to a staggering 70,000 cubic meters per second. Without this continuous replenishment, the Mediterranean’s sea level would plummet by about 1 meter each year, underscoring the vital role of this Atlantic connection. The cooler, relatively low-salinity Atlantic water then circulates eastward along the North African coasts, a dance that shapes the sea’s surface currents.

As this surface water flows eastward, particularly as it enters the eastern Mediterranean basin and circulates along the Libyan and Israeli coasts, it warms and its salinity increases due to evaporation. This process makes it denser, causing it to sink and form what is known as Levantine Intermediate Waters (LIW). These LIW, formed primarily along the coasts of Turkey, then circulate westward along the Greek and south Italian coasts, being the only waters that pass the Sicily Strait in a westward direction. Finally, after passing the Strait of Sicily, these waters continue along the Italian, French, and Spanish coasts before ultimately exiting the Mediterranean through the deeper parts of the Strait of Gibraltar, completing a remarkable circulatory loop that takes approximately 100 years for the water to complete, making the Mediterranean particularly sensitive to climate change.

14. **Dynamic Water Circulation: Transient Events and Future Sensitivities**Given its semi-enclosed nature, the Mediterranean Sea’s water circulation isn’t static; it’s also influenced by powerful, albeit temporary, ‘transitory events’ that can significantly alter its patterns over shorter timescales. These events highlight the dynamic and responsive character of the basin, making it a critical area for ongoing oceanographic research, especially in the context of a changing global climate. Such shifts can have profound implications for marine ecosystems, fisheries, and the overall health of the sea.

A notable example of such a transient event occurred in the mid-1990s, known as the Eastern Mediterranean Transient (EMT). During this period, unusually cold winter conditions led to the Aegean Sea becoming the primary area for deep water formation in the eastern Mediterranean, a significant shift from its usual sources. This temporary change in the origin of deep waters had major consequences for the entire water circulation system of the Mediterranean, illustrating how meteorological conditions can directly impact the deep ocean currents and stratification.

Another fascinating transient phenomenon affecting Mediterranean circulation is the periodic inversion of the North Ionian Gyre. This anticyclonic ocean gyre, typically observed in the northern Ionian Sea off the Greek coast, undergoes a transition from anticyclonic to cyclonic rotation. Such inversions dramatically change the local current patterns, influencing nutrient distribution and marine life in the affected areas. These transient events underscore the complexity of Mediterranean oceanography and its sensitivity to both localized and broader climatic pressures, making continuous monitoring and study crucial for understanding its future trajectory.

From its ancient past as a highway for empires to its intricate modern-day physical geography, the Mediterranean Sea continues to captivate and challenge us. Its complex network of marginal seas, vast drainage basin, myriad islands, unique climate, dynamic seabed, and intricate water circulation patterns all contribute to its unparalleled significance. As we continue to explore and understand its delicate balance, it becomes increasingly clear that this extraordinary body of water is not just a geographical feature, but a living, breathing entity that remains central to the lives of millions and the health of our planet.