The State of Israel, officially recognized as a country in the Southern Levant region of West Asia, stands at a unique and often contentious continental crossroads. Sharing borders with Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt, and possessing coastlines along the Mediterranean and Red Seas, its strategic location has long shaped its intricate history.

Central to its geopolitical narrative are the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, both of which Israel occupies. This occupation, alongside the Syrian Golan Heights in the northeast, forms a significant dimension of the country’s modern identity and its enduring conflicts.

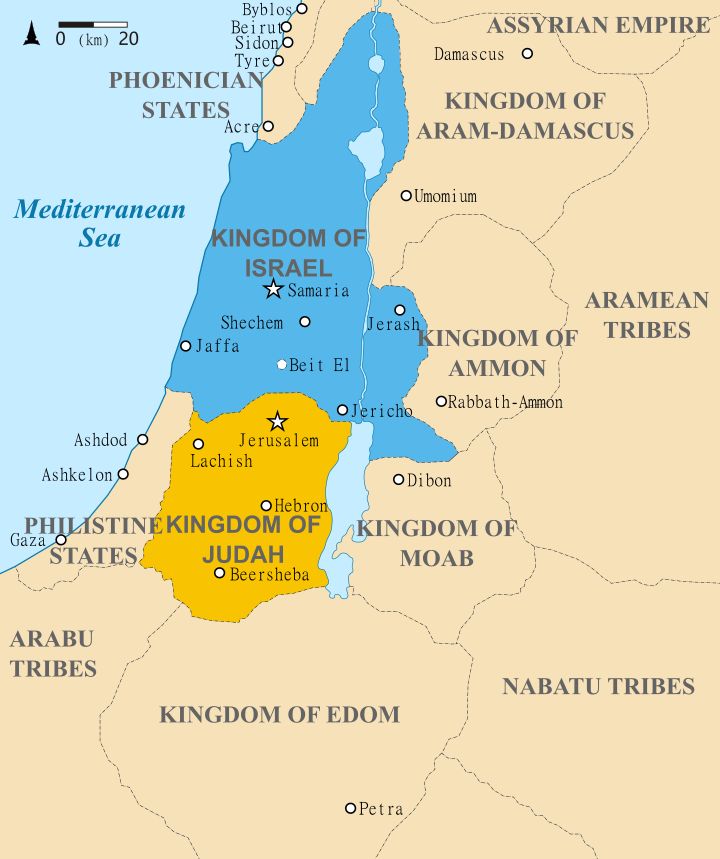

The historical tapestry of this land is remarkably rich, with layers of civilizations and empires shaping its character. Known by various names throughout antiquity—including the Land of Israel, Canaan, the Holy Land, the Palestine region, and Judea—it was once home to the Canaanite civilization before the emergence of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

Archaeological evidence points to human presence in the region as far back as 1.5 million years ago at the Ubeidiya site, with findings of anatomically modern humans from Misliya Cave dating to 200,000 years ago. The Natufian culture around 10,000 BCE introduced sedentism, marking a profound shift in human settlement patterns. The Neolithic Revolution brought agriculture, as evidenced by sites like Nahal Oren.

During the Bronze and Iron Ages, ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian texts from around 2000 BCE mention “Canaan” and “Canaanites,” structured as independent city-states. The Late Bronze Age saw large parts of Canaan become vassal states of the New Kingdom of Egypt. The subsequent Late Bronze Age collapse plunged Canaan into chaos, leading to the erosion of Egyptian control.

Modern archaeological accounts suggest that the Israelites and their culture branched out from the Canaanite peoples, developing a distinct monolatristic—and later monotheistic—religion centered on Yahweh. They spoke an archaic form of Hebrew, known as Biblical Hebrew. Around the same time, the Philistines settled on the southern coastal plain, adding another layer to the region’s diverse early inhabitants.

The existence and extent of the early Kingdoms of Israel and Judah have been subjects of scholarly debate. However, historians and archaeologists largely agree that the northern Kingdom of Israel was established by approximately 900 BCE, followed by the Kingdom of Judah around 850 BCE. The Kingdom of Israel, with its capital at Samaria, emerged as the more prosperous of the two, evolving into a regional power that controlled significant territories.

This powerful northern kingdom was ultimately conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire around 720 BCE. The Kingdom of Judah, under Davidic rule with Jerusalem as its capital, became a client state first to the Neo-Assyrian Empire and later to the Neo-Babylonian Empire. A significant turning point arrived in 587/6 BCE when King Nebuchadnezzar II besieged and destroyed Jerusalem and Solomon’s Temple following a revolt, dissolving the kingdom and exiling much of the Judean elite to Babylon.

Classical antiquity brought further imperial shifts and conflicts to the region. After capturing Babylon in 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire, issued a proclamation allowing the exiled Judean population to return, leading to the completion of the Second Temple around 520 BCE. The Achaemenids governed the region as the province of Yehud Medinata.

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the region, incorporating it into his vast empire. Following his death, the area was contested and controlled by the Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires as part of Coele-Syria. The Hellenization of the region over ensuing centuries created cultural tensions that culminated in the Maccabean Revolt of 167 BCE, which weakened Seleucid rule and led to the rise of the semi-autonomous Hasmonean Kingdom of Judea, eventually achieving full independence and expanding its territory.

The Roman Republic’s influence began in 63 BCE, initially taking control of Syria before intervening in the Hasmonean civil war. This intervention led to the installation of Herod the Great as a dynastic vassal of Rome. In 6 CE, the area was formally annexed as the Roman province of Judaea, sparking a series of Jewish–Roman wars due to tensions with Roman rule.

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE) resulted in the widespread destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple, alongside significant loss of life and displacement. A second major uprising, the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE), briefly allowed for an independent Jewish state, but it was brutally crushed by the Romans. This suppression devastated and depopulated Judea’s countryside, leading to Jerusalem being rebuilt as a Roman colony (Aelia Capitolina) and the province of Judea being renamed Syria Palaestina. Jews were expelled from the districts surrounding Jerusalem, though a continuous small Jewish presence endured, with Galilee becoming a new religious center.

Late antiquity and the medieval period witnessed a continued evolution of the region’s religious and political landscape. Early Christianity emerged, displacing Roman paganism in the 4th century CE, with Constantine promoting it and Theodosius I establishing it as the state religion. A series of laws discriminated against Jews and Judaism, leading to persecution by both the church and authorities, and many Jews emigrated to flourishing diaspora communities.

By the mid-5th century, a Christian majority had emerged locally, influenced by both Christian immigration and local conversion. Samaritan revolts erupted towards the end of the 5th century and continued into the late 6th century, significantly decreasing the Samaritan population. The Byzantine Empire briefly reconsolidated control after the Sasanian conquest of Jerusalem and a short-lived Jewish revolt in 614 CE.

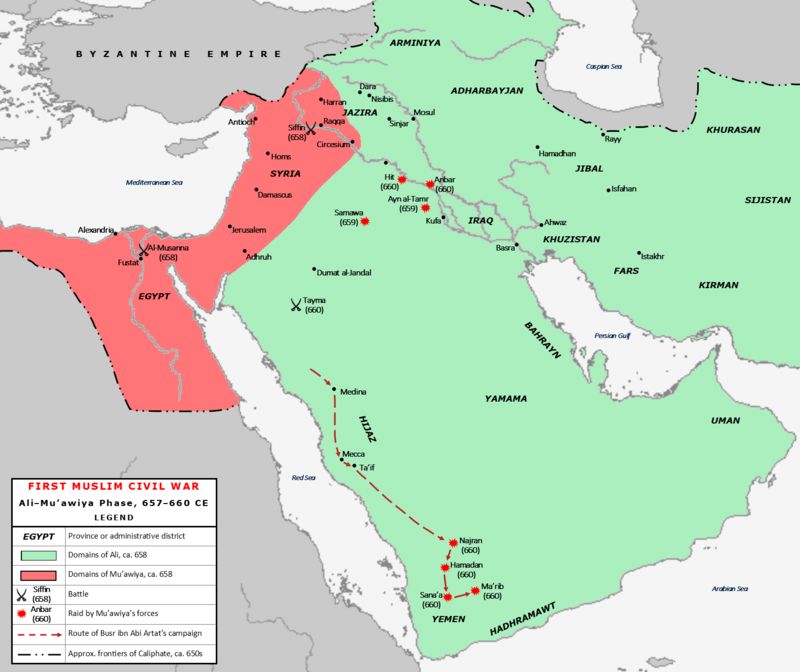

However, the Rashidun Caliphate conquered the Levant between 634 and 641 CE. Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab lifted the Christian ban on Jews entering Jerusalem, permitting them to worship there. Over the next six centuries, control of the region transitioned among the Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid caliphates, and subsequently the Seljuk and Ayyubid dynasties, leading to a drastic decrease in population and steady Arabisation and Islamisation.

The end of the 11th century ushered in the Crusades, papally-sanctioned incursions by Christian crusaders aimed at wresting Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control and establishing Crusader states. The Ayyubids eventually pushed back the crusaders, and Muslim rule was fully restored by the Mamluk sultans of Egypt in 1291, marking another significant shift in the region’s governance.

The modern period saw the region come under Ottoman Empire rule in 1516, governing it as part of Ottoman Syria. The Levant during this period was notably cosmopolitan, offering religious freedoms for Christians, Muslims, and Jews under the Ottoman Empire’s millet system. Under this system, non-Muslims were considered dhimmi, or protected, in exchange for loyalty and payment of the jizya tax, although they faced certain geographic and lifestyle restrictions that were not always strictly enforced.

In 1561, the Ottoman sultan invited Sephardi Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition to settle in and rebuild Tiberias, illustrating a period of relative tolerance. Despite this, two violent incidents occurred against Jews in Safed and Hebron in 1517 after the Ottomans ousted the Mamluks. Later, in the second half of the 18th century, Eastern European Jews, known as the Perushim, settled in Palestine, further diversifying the Jewish presence known as the Old Yishuv.

The concept of the “return” remained a symbolic and religious belief within Judaism, distinct from modern European nationalism. However, European antisemitism in the late 19th century galvanized Zionism, a political movement that sought to establish a Jewish state in Palestine as a solution to the “Jewish question.” This movement gained British support with the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

After World War I, Britain occupied the region and established Mandatory Palestine in 1920 under terms that included the Balfour Declaration and similar provisions for Arab Palestinians. The population was predominantly Arab and Muslim, with Jews accounting for about 11% and Arab Christians about 9.5%. Increased Jewish immigration, particularly with the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, fueled intercommunal conflict between Jews and Arabs, escalating into a civil war in 1947 after the United Nations proposed partitioning the land.

Arab opposition to British rule and Jewish immigration led to the 1920 Palestine riots and the formation of Jewish militias like the Haganah. The British introduced restrictions on Jewish immigration with the White Paper of 1939, leading to clandestine efforts to bring Jewish refugees to Palestine. By the end of World War II, 31% of the population of Palestine was Jewish, and the UK faced a Jewish insurgency over immigration restrictions and continued conflict with the Arab community.

The situation reached a critical point in July 1946 when the Irgun bombed the British administrative headquarters, killing 91, in response to British raids. The Jewish insurgency persisted, and British efforts to mediate with Jewish and Arab representatives failed. The Jews were unwilling to accept any solution that did not involve a Jewish state, suggesting partition, while the Arabs were adamant that a Jewish state in any part of Palestine was unacceptable, advocating for a unified Palestine under Arab rule.

In February 1947, the British referred the Palestine issue to the newly formed United Nations, which on November 29, 1947, adopted Resolution 181 (II) proposing a partition plan for an independent Arab State, an independent Jewish State, and an internationally governed Jerusalem. The Jewish Agency accepted the plan, which assigned 55–56% of Mandatory Palestine to the Jews, who constituted about a third of the population and owned 6–7% of the land at the time. The Arab League and Arab Higher Committee rejected it, leading to a civil war.

On May 14, 1948, the day before the British Mandate expired, David Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz-Israel. The following day, armies from Egypt, Syria, Transjordan, and Iraq, along with contingents from Yemen, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan, entered what had been Mandatory Palestine, initiating the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. The stated purpose of the invasion by the Arab League was to restore order and prevent further bloodshed.

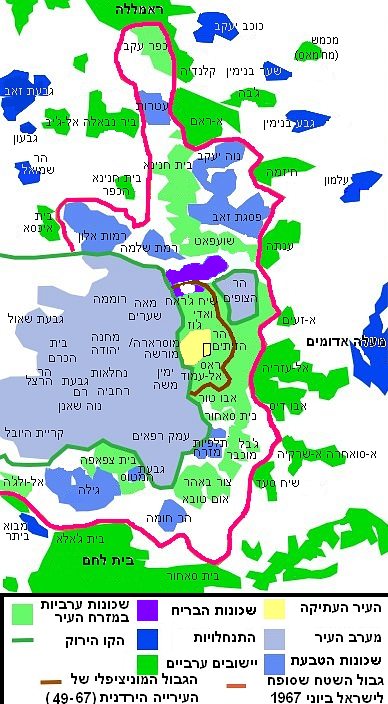

After a year of fighting, a ceasefire was declared, establishing temporary borders known as the Green Line. Jordan annexed what became the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip. This conflict led to over 700,000 Palestinians either fleeing or being expelled, an event known in Arabic as the Nakba, meaning ‘catastrophe,’ which devastated Palestine’s Arab culture, identity, and national aspirations. Around 156,000 Arabs remained, becoming Arab citizens of the new state of Israel.

Israel was admitted as a member of the UN on May 11, 1949. The early years of the state saw the Labour Zionist movement, led by Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, dominate Israeli politics. An influx of Holocaust survivors and Jews from Arab and Muslim countries to Israel between 1948 and 1951 dramatically increased the Jewish population from 700,000 to 1,400,000, reaching two million by 1958. This mass immigration, partly driven by Zionist beliefs and the promise of a better life, and partly by persecution or expulsion from their homes, led to temporary housing in camps known as ma’abarot.

During the 1950s, Israel faced frequent attacks by Palestinian fedayeen, primarily against civilians, originating mainly from the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip. These attacks prompted several Israeli reprisal operations. In 1956, Israel joined a secret alliance with the UK and France during the Suez Crisis, overrunning the Sinai Peninsula, prompted by Egypt’s nationalization of the Suez Canal, continued blockade of Israeli shipping, and increasing fedayeen attacks. Although pressured to withdraw by the UN, the war resulted in a significant reduction of Israeli border infiltration.

In May 1967, Egypt massed its army near the border with Israel, expelled UN peacekeepers from the Sinai, and blocked Israel’s access to the Red Sea, prompting other Arab states to mobilize. Israel, viewing these actions as a casus belli, launched a pre-emptive strike (Operation Focus) against Egypt in June. The ensuing Six-Day War saw Israel capture and occupy the West Bank from Jordan, the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the Golan Heights from Syria. Jerusalem’s boundaries were enlarged to incorporate East Jerusalem, and the 1949 Green Line became the administrative boundary between Israel and the occupied territories.

Following the 1967 war and the Arab League’s “Three Nos” resolution, Israel faced continued attacks from Egyptians in the Sinai during the 1967–1970 War of Attrition, and from Palestinian groups targeting Israelis globally and within Israel. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964, emerged as a dominant force, initially committing itself to “armed struggle as the only way to liberate the homeland.” In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Palestinian groups launched numerous attacks, including the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics, to which the Israeli government responded with assassination campaigns, bombings, and raids.

On October 6, 1973, Egyptian and Syrian armies launched a surprise attack against Israeli forces in the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, commencing the Yom Kippur War. Despite suffering significant losses, Israel repelled the combined Arab forces by October 25. Later peace efforts saw Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat’s historic trip to Israel in 1977, leading to the Camp David Accords (1978) and the Egypt–Israel peace treaty (1979). In return, Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula and agreed to enter negotiations over autonomy for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Despite these peace overtures, tensions continued. In 1980, the Jerusalem Law was passed, believed by some to reaffirm Israel’s 1967 annexation of Jerusalem, and in 1981, Israel effectively annexed the Golan Heights. These moves were largely rejected by the international community, with the UN Security Council declaring them null and void. Incentives for Israelis to settle in the occupied West Bank were provided, increasing friction with Palestinians.

In 1982, following a series of PLO attacks, Israel invaded Lebanon to dismantle PLO bases, destroying their military forces and decisively defeating the Syrians within six days. An Israeli government inquiry later held officials indirectly responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacre. The First Intifada, a Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule, erupted in 1987 with waves of uncoordinated demonstrations and violence in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, eventually becoming more organized and incorporating economic and cultural measures aimed at disrupting the Israeli occupation, resulting in over 1,000 deaths over six years.

The 1991 Gulf War saw the PLO support Saddam Hussein and Iraqi missile attacks against Israel, but Israel heeded American calls to refrain from retaliation. A major step in the peace process came in 1993, when Shimon Peres, on behalf of Israel, and Yasser Arafat, for the PLO, signed the Oslo Accords. These accords established mutual recognition and limited Palestinian self-governance in parts of the West Bank and Gaza. However, efforts to fully resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict after the interim Oslo Accords have not succeeded.

Israel continues to engage in several wars and clashes with Palestinian militant groups, and it continues to expand settlements across what are internationally recognized as illegally occupied territories, contrary to international law. Its practices in its occupation of the Palestinian territories have drawn sustained international criticism, accompanied by accusations from experts, human rights organizations, and UN officials that it has committed war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide against the Palestinian people. The Abraham Accords in the 2020s normalized relations with several more Arab countries, yet the core Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains unresolved.

Beyond these profound historical and geopolitical complexities, Israel stands as one of the most technologically advanced and developed countries globally. It boasts one of the largest economies in the Middle East and one of the highest standards of living in Asia, ranking highly in nominal GDP and GDP per capita. The nation proportionally invests more in research and development than any other country worldwide, a testament to its innovation. It is also widely believed to possess nuclear weapons. Israeli culture itself is a unique amalgamation of Jewish and Jewish diaspora elements, richly intertwined with Arab influences, reflecting the diverse heritage of the region.

The enduring narrative of Israel, its ancient roots, the tumultuous birth of the modern state, and its continuous engagement with the complexities of the Palestinian territories, particularly Gaza, underscores a deeply interwoven history. The story is one of relentless change, persistent conflict, and ongoing attempts at resolution, set against a backdrop of rich cultural heritage and a dynamic modern economy. It is a testament to the resilient human spirit and the profound challenges that persist in this ancient and modern land.