Russian, an East Slavic language, is a prominent member of the Balto-Slavic branch within the Indo-European language family. It is one of four surviving East Slavic languages and serves as the native tongue of the Russian people. Historically, it functioned as both the de facto and de jure official language of the former Soviet Union, reflecting its extensive influence and administrative importance across a vast geographic area.

In the present day, Russian retains official language status in the Russian Federation, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Beyond these nations, it continues to serve as a lingua franca, particularly in Ukraine, Moldova, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Its use also extends, to a lesser degree, into the Baltic states and Israel, a legacy of longstanding historical and demographic connections.

The Russian language maintains a substantial global presence, with more than 253 million speakers worldwide. Between 2020 and 2023, approximately 145 million were native speakers, while data from 2012 to 2020 recorded 108 million second-language speakers. These figures establish Russian as the most widely spoken native language in Europe and the most spoken Slavic language, underscoring its demographic prominence and cultural significance.

Russian: A Linguistic Powerhouse Spanning Continents and Centuries

Russian is the most geographically widespread language in Eurasia. It ranks seventh globally by number of native speakers and ninth by total speakers. Its international stature is reinforced by its status as one of two official languages used aboard the International Space Station and as one of the six official languages of the United Nations. It is also the fourth most widely used language on the Internet, reflecting its strong digital presence and accessibility in the modern world.

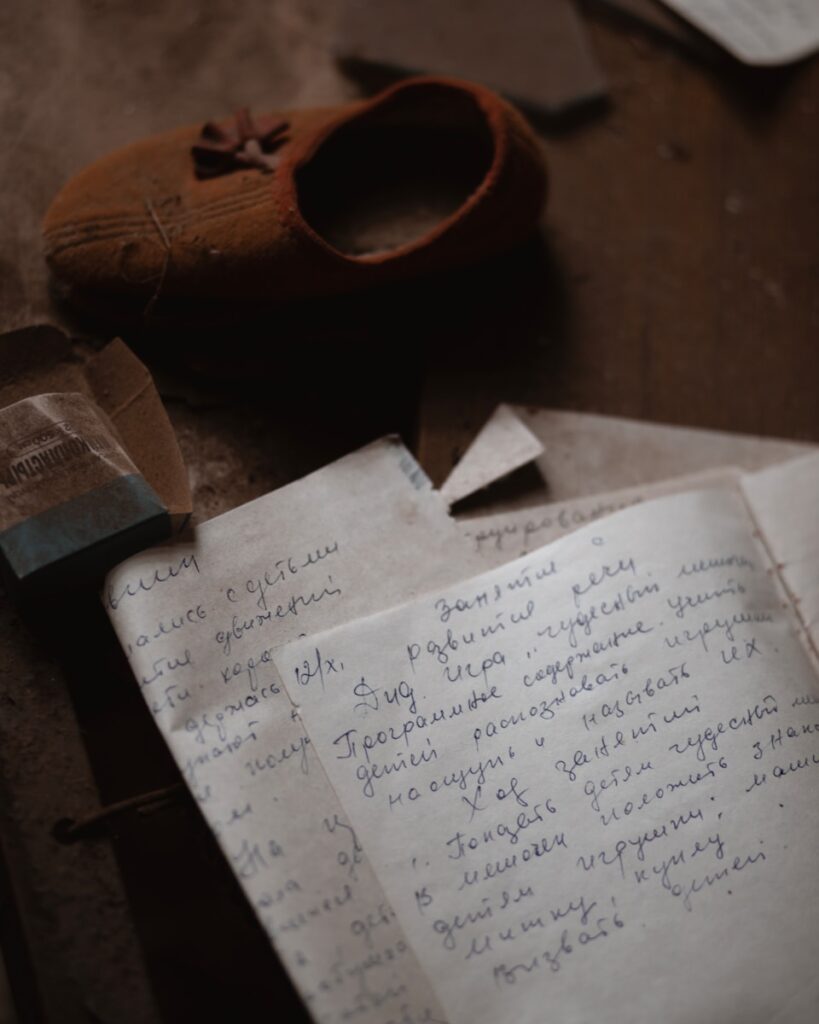

Written in the Cyrillic script, Russian employs the Russian alphabet, which evolved from the early Cyrillic alphabet adapted from Old Church Slavonic. A distinctive phonetic feature is its clear distinction between consonant phonemes with and without palatal secondary articulation, commonly referred to as “soft” and “hard” sounds. Nearly every consonant has both a hard and a soft form. This difference is usually indicated in writing by modifying the following vowel rather than altering the consonant itself.

Another notable phonological feature is the reduction of unstressed vowels. Stress placement in Russian is often unpredictable and is not typically marked in writing. An optional acute accent may be used to indicate stress, especially to differentiate between homographs, such as замо́к (zamók, “lock”) and за́мок (zámok, “castle”). This diacritic also assists in the correct pronunciation of rare words and proper nouns, improving clarity.

Linguistically, Russian belongs to the East Slavic subgroup of the Indo-European family. Its direct ancestor, Old East Slavic—also known as Old Russian—gave rise to modern Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian. In many regions of eastern and southern Ukraine, as well as throughout Belarus, these languages are spoken interchangeably. Centuries of bilingualism have fostered the emergence of mixed varieties, such as surzhyk in eastern Ukraine and trasianka in Belarus, which reflect the deep and enduring interaction between these related tongues.

Historical Roots and Linguistic Influences Shaping the Russian Language

The Novgorod dialect, a historical variety of Russian marked by distinctive northwestern features, is regarded by some scholars as having significantly influenced the development of modern Russian. The language also shares substantial lexical similarities with Bulgarian, largely due to the shared legacy of Church Slavonic. Despite this common foundation, Bulgarian grammar differs considerably from Russian, shaped by separate historical developments and linguistic interactions during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Over centuries, Russian has absorbed vocabulary and stylistic elements from a wide range of Western and Central European languages, including Greek, Latin, Polish, Dutch, German, French, Italian, and English. To a lesser extent, influences from Uralic, Turkic, Persian, Arabic, and Hebrew have also enriched its lexicon, reflecting both cultural exchanges and geopolitical interactions. These contributions have produced a linguistically diverse and intricate vocabulary that continues to evolve.

For native English speakers, Russian presents a significant learning challenge. The Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California classifies it as a Level III language, requiring approximately 1,100 hours of immersive instruction to attain intermediate proficiency. The path to a standardized national language was prolonged, complicated by the political fragmentation of Russian principalities and the period of Mongol rule, which intensified dialectal variations. The centralization of the Russian state in the 15th and 16th centuries reestablished a unified political, economic, and cultural space, fostering the eventual standardization of the language.

From Bureaucratic Necessity to Literary Standard: The Evolution of Modern Russian

The movement toward standardizing the Russian language began as a response to practical needs in government administration, where the lack of a consistent medium of communication created obstacles in legal, judicial, and bureaucratic affairs. Early standardization efforts drew upon the Moscow official, or chancery, language during the 15th to 17th centuries. Since that time, Russian language policy has sought to unify dialects among ethnic Russians and to promote Russian over other languages in certain contexts.

The contemporary standard, known as the modern Russian literary language, began to take shape in the early 18th century alongside the modernization reforms of Peter the Great. Rooted in the Moscow dialect, which itself developed from a northern dialectal base, it was influenced by the chancery language. The centralization of the Russian state attracted speakers of southern dialects to Moscow, creating a transitional dialect group that contributed to the literary norm.

Before the Bolshevik Revolution, the speech of the nobility and urban bourgeoisie differed significantly from that of the rural population, most of whom were peasants. The linguistic features of peasant speech were seldom examined by philologists, who largely treated it as a source of folklore rather than a serious subject of study. The dialectologist Nikolai Karinsky later acknowledged this gap, noting that “Scholars of Russian dialects mostly studied phonetics and morphology. Some scholars and collectors compiled local dictionaries. We have almost no studies of lexical material or the syntax of Russian dialects.”

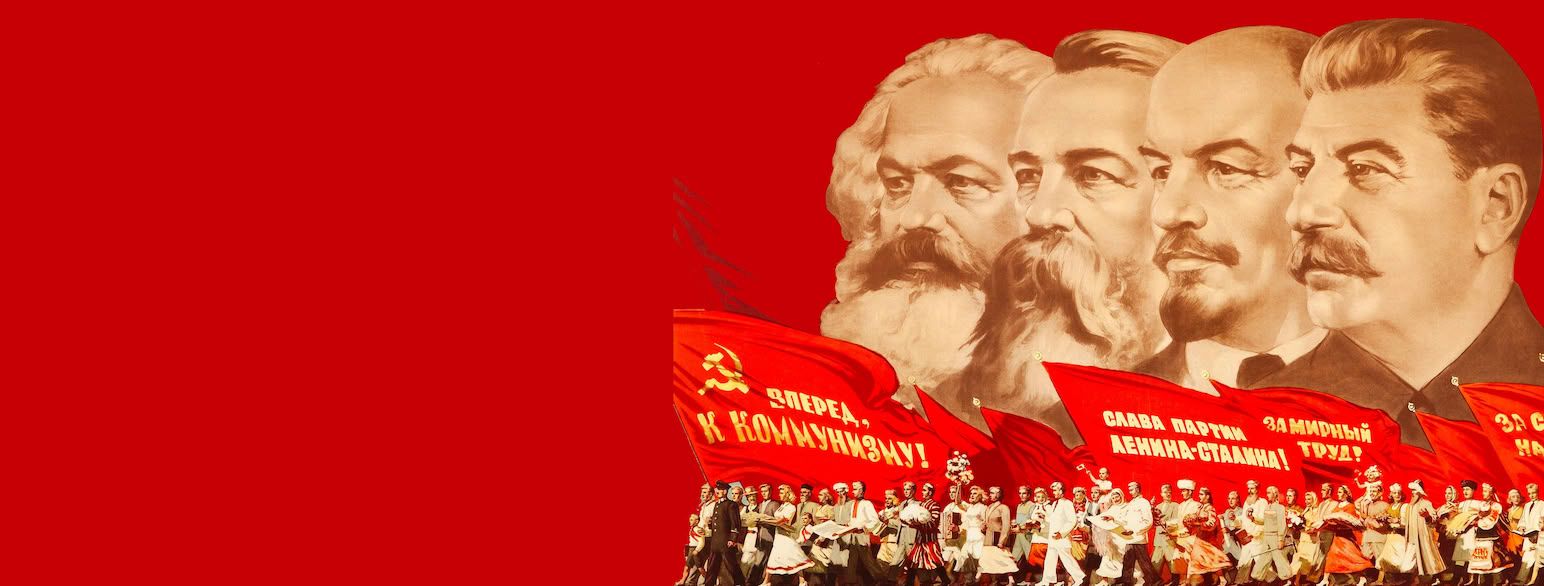

Soviet-Era Language Policy and the Global Reach of Russian

After 1917, Marxist linguists showed limited interest in the diversity of peasant dialects, regarding them as remnants of a rapidly vanishing past and thus unworthy of sustained scholarly study. Nakhimovsky cites the 1930 remarks of Soviet academicians A.M. Ivanov and L.P. Yakubinsky, who argued that peasant language, with its phonetics, grammar, and vocabulary inherited from feudalism, was destined for dissolution. As rural populations moved into industrial labor, local dialects were gradually leveled, giving rise to a “general language of the working class” shaped by urbanization and heavy industry. They suggested that capitalism itself tends toward creating a unified urban language within a society, a view that reflected the Soviet objective of linguistic homogenization.

The global distribution of Russian speakers is extensive. In 2010, there were an estimated 259.8 million speakers worldwide, including 137.5 million in Russia, 93.7 million across the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Baltic countries, and 12.9 million in Eastern Europe. Other concentrations included 7.3 million in Western Europe, 2.7 million in Asia, 1.3 million in the Middle East and North Africa, 0.1 million in Sub-Saharan Africa, 0.2 million in Latin America, and 4.1 million across the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

This global presence positioned Russian as the seventh most widely spoken language in the world, following English, Mandarin, Hindi-Urdu, Spanish, French, Arabic, and Portuguese. Its role as one of the six official languages of the United Nations reinforces its importance in international diplomacy. Russian remains a significant language of education both for native speakers and for learners of Russian as a second language, and it continues to hold cultural and practical value in many former Soviet republics.

Russian Language Use and Policy in Belarus and the Baltic States

In Belarus, Russian is recognized as a second state language alongside Belarusian under the Constitution. In 2006, 77% of the population reported fluency in Russian, with 67% using it as their primary language at home, with friends, or in the workplace. The 2019 census recorded 5,094,928 people, or 54.1% of the population, identifying Belarusian as their native language. In everyday life, however, Russian dominates, with 6,718,557 people (71.4%) speaking it at home. This includes 61.4% of ethnic Belarusians, 97.2% of Russians, 89.0% of Ukrainians, 52.4% of Poles, and 96.6% of Jews. By contrast, 2,447,764 people (26.0%) speak Belarusian at home, the highest proportion being among ethnic Poles at 46.0%.

In Estonia, Russian is classified as a foreign language, though spoken by 29.6% of the population according to a 2011 estimate. The role of Russian in education has been politically contentious. In 2022, the Estonian parliament approved a law mandating the closure of all Russian-language schools and kindergartens by the 2024–2025 academic year, initiating a transition to Estonian-only instruction. Latvia similarly designates Russian as a foreign language. In 2006, 55% of Latvians were fluent in Russian, with 26% using it as their primary language in daily interactions. A 2012 constitutional referendum to make Russian a second official language was rejected by 74.8% of voters. Since 2019, Russian-language instruction has been gradually removed from private higher education institutions and public secondary schools. Legislation passed in 2022 requires all schools and kindergartens to switch to Latvian-only education by 2025, and a 2023 decision will end state funding for Russian-language media from 2026.

In Lithuania, Russian has no official status, though it remains spoken in some areas, particularly among older generations. English has largely replaced Russian as the primary foreign language, with around 80% of young people now speaking English first. The Russian-speaking minority in Lithuania is relatively small, representing 5.0% of the population in 2008, and 7.2% citing Russian as their native language in the 2011 census.

Shifting Legal and Social Status of the Russian Language in Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine

Moldova once recognized Russian as the language of interethnic communication under a Soviet-era law. This changed on January 21, 2021, when the Constitutional Court of Moldova declared the law unconstitutional, removing Russian from this status. In 2006, 50% of Moldovans reported fluency in Russian, with 19% using it as their primary language in daily life. The 2014 census recorded ethnic Russians at 4.1% of the population, 9.4% identifying Russian as their native language, and 14.5% speaking it regularly.

In Russia, the 2010 census reported Russian language proficiency among 138 million people, accounting for 99.4% of respondents, a slight decrease from the 2002 census figure of 142.6 million, or 99.2%. In Ukraine, Russian continues to hold significance as a minority language. Data from Demoskop Weekly in 2004 estimated 14.4 million native speakers and 29 million active speakers. In 2006, 65% of the Ukrainian population was fluent, and 38% used Russian as their main language.

In recent years, legislative reforms in Ukraine have redefined the role of Russian in public life. On September 5, 2017, the Ukrainian Parliament adopted a new education law mandating that all schools provide instruction at least partially in Ukrainian, while permitting the use of indigenous and minority languages alongside it. This law drew criticism from officials in Russia and Hungary. Further changes came in 2019 with the Law of Ukraine “On Protecting the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language,” which prioritizes Ukrainian in more than 30 public domains, including administration, media, education, and services, while leaving private communication unregulated.

Russian Language Presence and Policy Shifts Across Asia

Across Asia, the role of Russian varies significantly. In China, it has no official status but is spoken by small Russian communities in northeastern Heilongjiang and northwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Between 1949 and 1964, Russian was the primary foreign language taught in Chinese schools. In Kazakhstan, while not designated a state language, Article 7 of the Constitution grants it equal standing with Kazakh in state and local administration. According to the 2009 census, 10,309,500 people, or 84.8% of the population aged 15 and above, could read, write, and understand spoken Russian. However, a media law drafted in October 2023 aims to raise the share of Kazakh-language content on television and radio from 50% to 70% by 2025, thereby reducing Russian-language programming.

In Kyrgyzstan, Russian is a co-official language under Article 5 of the Constitution. The 2009 census recorded 482,200 native speakers, representing 8.99% of the population, and 1,854,700 fluent second-language speakers, comprising 49.6% of residents aged 15 and above. In Tajikistan, Russian is recognized as the language of inter-ethnic communication and is authorized for use in official documentation. Data from 2006 show that 28% of the population was fluent, with 7% using it as their primary language. It remains prevalent in government and business.

In Turkmenistan, Russian lost its official lingua franca status in 1996. Only around 12% of the population who came of age during the Soviet era retain proficiency, and younger generations generally lack familiarity with the language. Russian-language education in primary and secondary schools is nearly absent. In Uzbekistan, an undated estimate indicates that 14.2% of the population speaks Russian. In Mongolia, Russian was the most widely taught foreign language in 2005, and by 2006 it was mandatory as a second foreign language from Year 7 onward.

Russian Language Influence in Israel, North America, and Global Institutions

As of 2017, approximately 1.5 million Israelis spoke Russian. The language maintains a strong presence in the Israeli media landscape, with newspapers, websites, television stations, schools, and social media producing extensive content in Russian. Israel Plus, a national television channel, broadcasts primarily in Russian. Russian is also spoken by a small number of second-language speakers in Afghanistan, and in Vietnam it has been incorporated into the elementary curriculum, enjoying the same “first foreign language” status as English, Chinese, and Japanese.

In North America, Russian was introduced during the 18th century when explorers claimed Alaska for Russia. Although most colonists left after the United States purchased Alaska in 1867, a small number remained, preserving the language in isolated communities. Nikolaevsk, Alaska, continues to have a higher proportion of Russian speakers than English speakers. Significant Russian-speaking populations also live in major cities across the United States and Canada, including New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, Los Angeles, Toronto, and Vancouver. Many maintain Russian-language newspapers and reside in ethnic enclaves, particularly among immigrant groups arriving from the early 1960s onward. Notably, only about 25% of these Russian speakers are ethnic Russians. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russian-speaking Jews dominated communities such as Brighton Beach in Brooklyn, New York. Subsequent migration from former Soviet republics diversified these populations, adding ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Central Asians, and more Russian-speaking Jews. The 2007 United States Census reported that over 850,000 residents spoke Russian at home.

Russian is also an official or working language in numerous international organizations. These include the United Nations, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the World Health Organization, the International Civil Aviation Organization, UNESCO, and the World Intellectual Property Organization. It is similarly employed by the International Telecommunication Union, the World Meteorological Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the International Criminal Court, and the International Olympic Committee. Further recognition is found in the Universal Postal Union, the World Bank, the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Eurasian Economic Community, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat, the International Organization for Standardization, and the International Mathematical Olympiad.

The Russian language employs the Cyrillic alphabet, which has evolved significantly from its Old Church Slavonic origins. The modern Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters, refined through a series of reforms culminating in the 1917–1918 orthographic revision. Several archaic letters such as ⟨ѣ⟩ and ⟨і⟩ were phased out, merging into contemporary characters or undergoing graphic modifications. Historically, the yers ⟨ъ⟩ and ⟨ь⟩ marked ultra-short vowels but now serve different orthographic functions. Due to technological constraints and the absence of Cyrillic keyboards internationally, transliteration into the Latin alphabet remains common, though the adoption of Unicode has facilitated native Cyrillic usage even on Western QWERTY keyboards. The Russian language’s digital integration dates back to the 1950s with the M-1 and MESM computing systems. The Institute of Russian Language endorses the use of an optional acute accent to indicate stress, which is essential for distinguishing homographs and clarifying pronunciation in dictionaries and educational texts.

Phonologically, Russian exhibits a complex syllabic structure permitting up to four consonants both before and after the vowel nucleus. A distinctive feature is the palatalization of consonants, where the tongue is raised during articulation, producing contrasting “soft” and “hard” consonant pairs. Some consonants, including /ts/, are generally hard, but loanwords may introduce palatalized variants. Dental articulation characterizes many consonants, while some linguists note velarization similar to that in Irish, especially before hard vowels. Russian vowels number five or six in stressed syllables, merging into fewer sounds when unstressed. This interplay of phonetic elements results in a rich and nuanced sound system that is a hallmark of the language.

Russian grammar retains a deeply synthetic and inflectional Indo-European structure, characterized by fusional morphology where single morphemes convey multiple grammatical meanings. The language’s syntax is flexible yet follows established conventions to ensure clarity and expressiveness. The intricate system of noun cases, verb conjugations, and gender distinctions reflects a long history of linguistic development. From its ancient East Slavic roots to its current global status, Russian embodies a resilient and adaptive linguistic tradition. Its phonological complexity, morphological depth, and historical richness continue to sustain its role as a vital medium for culture, diplomacy, and science worldwide.