In early December, Joseph Awuah-Darko, a 28-year-old Ghanaian artist and entrepreneur, made a profound and startling announcement on Instagram. He shared with the world his intention to die, driven by an exhaustive battle with bipolar disorder that had eroded his will to live. Having relocated to the Netherlands to pursue medically assisted death, his minute-long video, starting with the tearful declaration, “I’m just so tired,” quickly garnered widespread attention.

What followed his initial post, however, deviated dramatically from a somber farewell. Three days later, Mr. Awuah-Darko launched what he termed “The Last Supper Project.” He extended an unusual invitation: anyone willing to cook an at-home meal for him could sign up, and he would visit their home to converse, eat, and connect. His stated aim was to “find meaning again with people” during the time he believed he had left on earth.

The response was immediate and overwhelming. Within days, thousands of individuals reached out, transforming his personal journey into a public phenomenon. To date, Mr. Awuah-Darko has attended 152 Last Suppers, traveling extensively across Europe, including cities like Berlin, Paris, Antwerp, Milan, and numerous locations throughout the Netherlands and Amsterdam. His hosts have ranged from those preparing homemade dinners to those treating him to meals at high-end bistros, costing $100 per person, or even at Burger King.

Through videos and photographs shared on Instagram, set to soundtracks by artists like Debussy and Radiohead, Mr. Awuah-Darko has meticulously documented these interactions. The meals consistently appear convivial, frequently concluding with embraces. His followers, and his hosts, seem genuinely uplifted by his presence and his remarkable candor regarding his deepest turmoils. He functions as a charismatic figure, akin to a Gen Z home-cooking show host, yet he brings an unparalleled rawness that resonates deeply with his audience.

He once recounted an experience with two sisters who served him a Persian dinner while he was in the grip of a depressive episode. He shared that he “cried heavily during the latter 2 hours of the dinner before they sent me home in a cab with a bouquet of flowers.” He observed that all he did was “show up and they held so much space for me,” a post that garnered 10,000 likes. An Instagram commenter captured the sentiment of many, writing, “If people will open their arms to a stranger to help them experience being alive more fully before choosing to exit forever, maybe there’s hope for all of us.”

However, not everyone has reacted with support. Mental health experts have expressed dismay, contending that Mr. Awuah-Darko’s project implicitly suggests that euthanasia is a viable solution for bipolar disorder, a condition widely recognized as treatable. Parents of depressed children have also voiced concern, arguing that his “farewell tour” inappropriately romanticizes suicide. One mother, whose daughter was in a “fragile, emotional and impressionable state,” directly appealed to him on Instagram, begging him to “shut it down” before he might “take my daughter with you.”

Beyond the ethical debate, a segment of detractors has questioned the authenticity of Mr. Awuah-Darko’s intentions, pondering if his project is a form of scam. A Reddit forum has emerged, compiling suspicions and detailing aspects of his past. These include a breach-of-contract lawsuit filed in Ghana last year for over $260,000 by an artist he once represented as an agent. Despite these doubts, Mr. Awuah-Darko does not financially profit directly from the dinners, often relying on hosts to cover his travel expenses. His primary stated income source is a Substack newsletter, generating approximately $2,000 per month.

The underlying purpose of Mr. Awuah-Darko’s project remains a subject of speculation: Is it performance art? An unconventional form of psychiatric treatment? Or merely a prolonged, catered farewell? Regardless, his unique blend of vulnerability and public display has attracted a significant following, growing to 542,000 Instagram followers, establishing him as an unexpected figure in the social media landscape, an “assisted-death influencer.” Yet, as of late July, an equally unexpected development emerged: a renewed reason for him to embrace life.

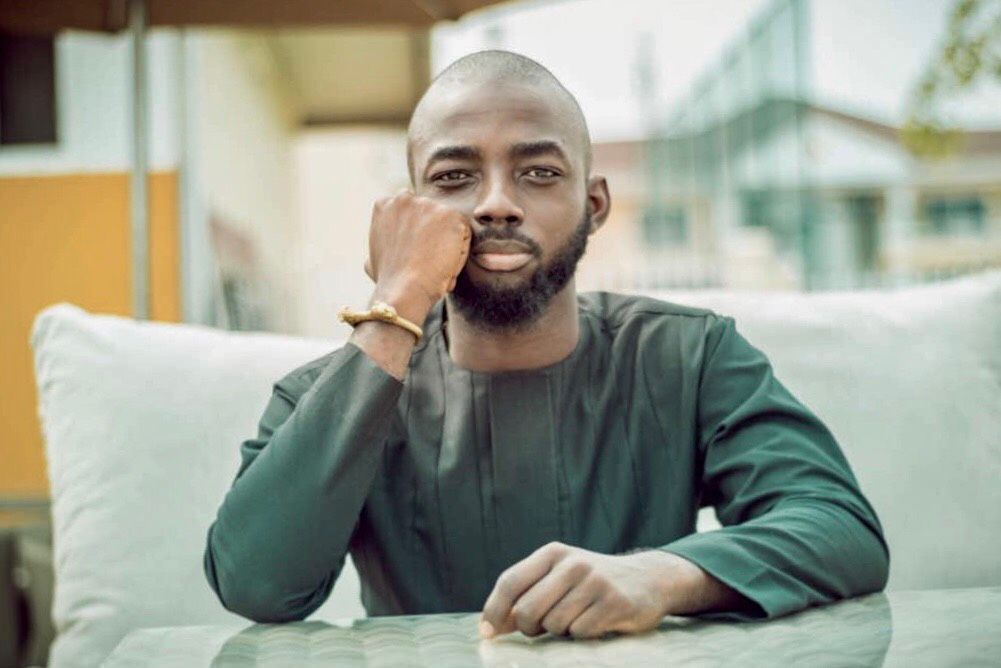

In late June, Mr. Awuah-Darko, an “elfin man with a shaved head, warm eyes and a wide smile,” met for lunch at a sidewalk cafe in Amsterdam. He presented as a compelling figure, dressed in a charcoal-black sweater with thumb holes, and carrying a Bottega Veneta handbag. His conversation style mirrored his thoughts: rapid and insightful. He explained, “I talk very fast,” and added, “I think even faster.”

Born in London and raised in Ghana, Mr. Awuah-Darko hails from one of the country’s wealthiest families, with his grandfather having founded an insurance company now at the core of a conglomerate valued at $650 million. However, he stated that his family has financially disowned him due to his open identification as gay, which is a criminal offense in Ghana. This alleged estrangement has led to periods of homelessness, with him occasionally sleeping outdoors or in hotel bathroom stalls. He currently resides with a Dutch couple in Amsterdam, sleeping on their sofa, remarking, “I have the nicest version of homelessness now.”

For years, Mr. Awuah-Darko, a painter of vividly colored abstract art, utilized Instagram to share uplifting messages with fellow artists through his “Dear Artist” series, which amassed around 200,000 followers. However, as his mental state deteriorated, he found this content increasingly inauthentic. His diagnosis of bipolar disorder at age 16 left him feeling overwhelmed by hopelessness during low points, struggling even to leave his bed. The announcement of the Last Supper Project, despite its macabre undertones, seemingly tapped into profound human empathy, leading to a rapid and steady increase in his follower count.

His ability to articulate his inner world is remarkable. During a dinner in Rotterdam hosted by a 21-year-old student named Sydney Gruis, Mr. Awuah-Darko spoke almost continuously for the first hour, captivating his audience. He discussed a wide array of topics, from his grandparents’ meeting to his affection for Francis Bacon, his identity as “a writer who paints, not a painter who writes,” and his “tragically privileged” childhood. His conversations, a “marathon jazz performance with a limited number of notes,” delve into his past, his failures, triumphs, and the luminaries he admires.

He confessed, “I definitely love the ability and the capacity I have to download or externally process what I’m thinking, what I’m going through.” He added, “I do it because I have this weird desire to make sure that I’m not misunderstood, or make sure that people understand that I’m maybe more than meets the eye.” He is self-aware, even acknowledging potential accusations of narcissism. His Instagram once began with the stark declaration, “I AM NOT A GOOD PERSON,” pre-empting criticism and offering more material to explore. He sees himself as a “barefoot anthropologist,” comfortable discussing “really, really difficult things.”