The Irish, known in their native tongue as Na Gaeil or Na hÉireannaigh, constitute an ethnic group and nation rooted deeply in the island of Ireland. This collective shares a common ancestry, a rich and intricate history, and a vibrant cultural tapestry that has evolved over millennia. While the island has hosted humans for approximately 33,000 years, it has been continuously inhabited for over 10,000 years, a testament to its enduring allure and historical significance.

Throughout most of its recorded history, the Irish have predominantly been a Gaelic people. Their narrative, however, is not one of isolation, but rather a dynamic interplay of indigenous development and external influences. From the 9th century, Vikings established settlements, leading to the emergence of the Norse-Gaels, enriching the island’s cultural blend.

The 12th century saw Anglo-Norman conquests, further altering the demographic and political landscape. Subsequent English and Lowland Scots colonization in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the north, introduced new populations to parts of the island. Today, Ireland is formally divided into the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, with the people of Northern Ireland embracing diverse national identities, including Irish, British, or a combination thereof.

Delving into the prehistoric antecedents, Ireland has consistently drawn various peoples to its shores over the past 33,000 years. Historical accounts suggest that Pytheas, during his voyage of exploration around 325 BC, was the first known scientific visitor to observe and describe the Celtic and Germanic tribes, providing an early external glimpse into the region.

The very names “Irish” and “Ireland” are believed to have originated from the goddess Ériu, linking the land and its people to ancient mythological roots. The island was home to a multitude of tribal groups and dynasties, such as the Airgialla, Fir Ol nEchmacht, Delbhna, and the mythical Fir Bolg. Notably, some tribes, including the Conmaicne and Delbhna, derived their names from their chief deities, while others like the Ciannachta and Eóganachta, potentially from deified ancestors, a practice mirrored in Anglo-Saxon dynasties.

Legendary narratives recount the descent of the Irish from the Milesians, who are said to have conquered Ireland around 1000 BC or later. These foundational myths contribute to the deep sense of shared ancestry and historical continuity that defines the Irish identity, weaving a complex narrative that blends factual history with rich folklore.

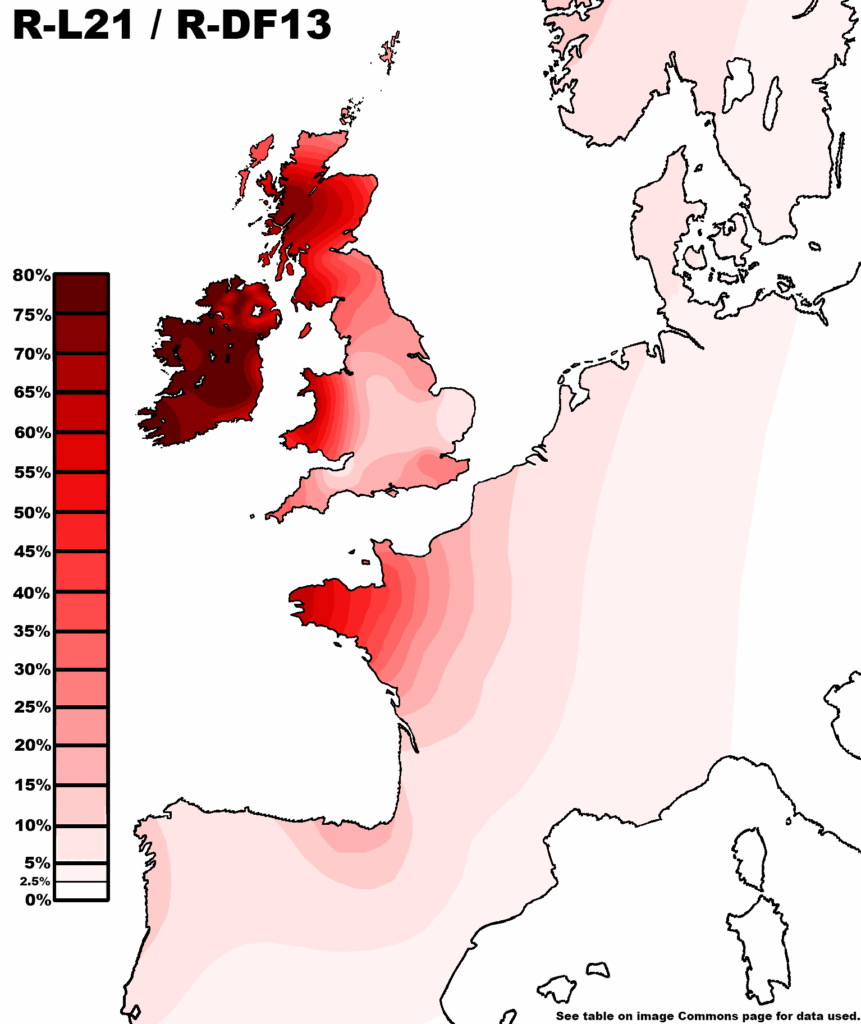

Modern genetic studies provide remarkable insights into the deep history of the Irish people, revealing a strong genetic continuity from the Bronze Age. Key genetic traits have been present in Ireland for approximately 4,000 years, dating back to the early Bronze Age. The highest global frequencies of the R-L21 Y-chromosome haplotype and lactase persistence, the ability to digest milk into adulthood, are uniquely found among people in Ireland.

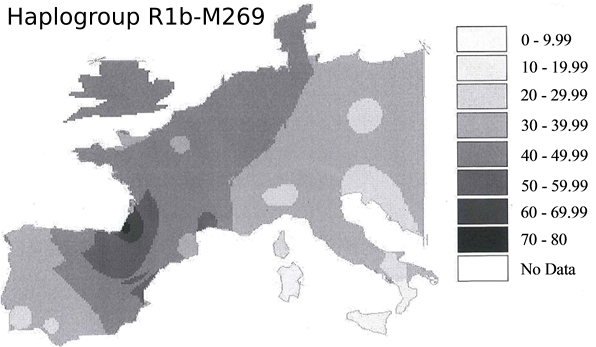

Haplogroup R1b is the predominant haplogroup among Irish males, reaching nearly 80%, a pattern also observed across most of Western Europe. Within this, R1b-L21 stands as the dominant sub-clade throughout Ireland, appearing in 65% of the population. This subclade, also prevalent in Scotland, Wales, and Brittany, points to a common ancestor who lived around 2,500 BC.

The genetic makeup of modern Irish people reflects a small contribution from Early European Farmers of the Neolithic period, with the majority of their ancestry tracing back to Western Steppe Herders. These herders originated from the Pontic-Caspian steppe and migrated into western Europe during the early Bronze Age, shaping the genetic landscape of the region.

A significant archaeogenetics study of ancient remains from Ireland revealed that the older Neolithic farming population bore resemblance to present-day Sardinians. In contrast, three Bronze Age men buried on Rathlin Island between 2000–1500 BC exhibited genetic profiles most similar to contemporary Irish people. All three belonged to Haplogroup R-L21 and carried the gene for lactase persistence, underscoring a robust genetic continuity in Ireland from the Bronze Age to the present era.

It is widely suggested that these Bronze Age people, characterized by the R-L21 haplogroup, introduced the Bell Beaker culture to Ireland. Furthermore, they are believed to have brought an Indo-European language, which served as an ancestor to the Insular Celtic and Gaelic languages. Today, the R-L21 haplogroup remains dominant across the island of Ireland, western Scotland, Wales, and Brittany, firmly associating it with the Insular Celtic peoples.

A 2017 genetic study further refined the understanding of the Irish population’s genetic structure, dividing it into ten distinct geographic genetic clusters. Seven of these clusters represent ‘Gaelic’ Irish ancestry, while three show a shared Irish-British heritage. The subtle distinctions among the ‘Gaelic’ clusters remarkably align with historical boundaries of Irish provinces and kingdoms, illustrating long-standing regional genetic patterns.

The most pronounced genetic difference exists between native ‘Gaelic’ Irish populations and Ulster Protestants, the latter known for more recent, partial British ancestry. Additionally, the study found the Irish to share most similarity with two primary ancestral sources: a ‘Northwestern France’ component, highest in Irish and other Celtic populations (Welsh, Highland Scots, Cornish), and a ‘West Norway’ component, linked to the Viking era.

Compared to their Celtic neighbors in Scotland and Wales, who have approximately 30% of their genomes of Anglo-Saxon origin, Irish people possess the least amount of Anglo-Saxon ancestry in the British Isles, around 10%. This distinction highlights a unique genetic trajectory within the region.

The term “Black Irish” sometimes refers to Irish people with dark hair and eyes, with one theory attributing this to descendants of Spanish traders or shipwrecked Spanish Armada sailors, though little evidence supports this. As of 2016, a distinct community of 10,100 Irish nationals of African descent identified themselves as “Black Irish” in the national census, reflecting evolving contemporary identities.

Irish Travellers represent a distinct ethnic people of Ireland. A DNA study indicates their original descent from the general Irish population, yet they are now genetically very distinct. The emergence of Travellers as a separate group is estimated to have occurred around 1597, long before the Great Famine, possibly coinciding with the Plantation of Ulster, which displaced native Irish from their lands and may have contributed to a nomadic population.

The ancient history of the Irish people, as recorded by a Roman historian, suggests a division into “sixteen different nations” or tribes. Despite traditional histories asserting that the Romans never conquered Ireland, the Irish were not isolated; they frequently raided Roman territories and maintained significant trade links, demonstrating their active engagement with the wider European world.

Prominent figures of ancient Irish history include the High Kings of Ireland, such as Cormac mac Airt and Niall of the Nine Hostages, alongside the semi-legendary Fianna. The 20th-century writer Seumas MacManus eloquently observed that even if the Fianna and the Fenian Cycle were purely fictional, they would still reflect the inherent character of the Irish people, embodying ideals of a “beautiful-souled people, capable of appreciating lofty ideals.”

The advent of Christianity to the Irish in the 5th century marked a profound shift in their foreign relations. Remarkably, the only recorded military raid abroad after this conversion is a presumed invasion of Wales around the 7th century, underscoring a significant transformation. MacManus highlighted this profound change, stating, “If we compare the history of Ireland in the 6th century, after Christianity was received, with that of the 4th century, before the coming of Christianity, the wonderful change and contrast is probably more striking than any other such change in any other nation known to history.

Following their conversion to Christianity, Irish secular laws and social institutions largely persisted. The Middle Ages witnessed further migrations and invasions that shaped Irish society. The traditional view suggests that Goidelic language and Gaelic culture were introduced to Scotland in the 4th or 5th century by Irish settlers who founded the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata on Scotland’s west coast.

Archaeologist Ewan Campbell challenges this traditional narrative, arguing against a significant migration or elite takeover due to a lack of archaeological and placename evidence. He critiques the uncritical acceptance of the “Irish migration hypothesis,” stating it “seems to be a classic case of long-held historical beliefs influencing not only the interpretation of documentary sources themselves but the subsequent invasion paradigm being accepted uncritically in the related disciplines of archaeology and linguistics.

Dál Riata eventually merged with the territory of the neighboring Picts to form the Kingdom of Alba, where Goidelic language and Gaelic culture became dominant, leading to the country being named Scotland after the Roman term for the Gaels: Scoti. The Isle of Man and the Manx people also experienced profound Gaelic influence throughout their history.

Irish missionaries played a crucial role in spreading Christianity, with figures like Saint Columba bringing the faith to Pictish Scotland. The Irish of this era were acutely “aware of the cultural unity of Europe,” exemplified by the 6th-century monk Columbanus, regarded as “one of the fathers of Europe.” Other Irish saints, including Aidan of Lindisfarne, Kilian, and Vergilius, became patron saints in various European locations.

Irish missionaries established influential monasteries across Europe, such as Iona Abbey, the Abbey of St Gall in Switzerland, and Bobbio Abbey in Italy. These centers of learning maintained a strong emphasis on Irish and Latin. Early Irish scholars displayed “almost a like familiarity that they do with their own Gaelic” concerning Latin. There is also evidence of Hebrew and Greek studies, with Greek likely taught at Iona.

Professor Sandys, in his History of Classical Scholarship, noted, “The knowledge of Greek… which had almost vanished in the west was so widely dispersed in the schools of Ireland that if anyone knew Greek it was assumed he must have come from that country.” This highlights the exceptional intellectual contributions of Irish scholars.

From the time of Charlemagne, Irish scholars commanded considerable presence and renown for their learning in the Frankish court. Johannes Scotus Eriugena, a 9th-century intellectual, stands out as an exceptionally original philosopher and an early founder of scholasticism, the dominant medieval philosophy. His extensive knowledge of Greek enabled him to translate many works into Latin, opening access to the Cappadocian Fathers and the Greek theological tradition, which were largely unknown in the Latin West until then.

The influx of Viking raiders and traders in the 9th and 10th centuries profoundly shaped Ireland’s urban landscape. They founded many of Ireland’s most important towns, including Cork, Dublin, Limerick, and Waterford, establishing urban centers where earlier Gaelic settlements had not achieved such scale. While the Vikings left a limited direct impact on Ireland beyond urban development and certain words integrated into the Irish language, many Irish individuals taken as slaves intermarried with Scandinavians, fostering a close link with the Icelandic people.

According to the Icelandic Laxdœla saga, even slaves in Iceland were considered “highborn, descended from the kings of Ireland.” The name Njáll Þorgeirsson, the main character of Njáls saga, is a variant of the Irish name Neil. Furthermore, Eirik the Red’s Saga recounts that the first European couple to have a child born in North America was descended from Aud the Deep-minded, the Viking Queen of Dublin, and a Gaelic slave brought to Iceland, illustrating the far-reaching influence of Irish people in the Norse world.

The arrival of the Anglo-Normans also brought Welsh, Flemish, Anglo-Saxons, and Bretons to Ireland. Most of these new settlers were assimilated into Irish culture and polity by the 15th century, with the exception of certain walled towns and the Pale areas, which maintained a distinct identity. The Late Middle Ages also saw the settlement of Scottish gallowglass families, who were of mixed Gaelic-Norse and Pict descent, primarily in the north; their linguistic and cultural similarities facilitated their assimilation into Irish society.

Irish surnames represent a unique and early development in European onomastics, as the Irish were among the first peoples to adopt surnames in the modern sense. It is customary for individuals of Gaelic origin to have English versions of their surnames starting with ‘Ó’ or ‘Mac’, though many have since been shortened to ‘O’ or ‘Mc’. The prefix ‘O’ originates from the Irish Ó, itself from Ua, meaning “grandson” or “descendant” of a named person, while Mac is the Irish word for son.

Common ‘O’ surnames include Ó Briain (O’Brien), Ó Ceallaigh (O’Kelly), Ó Conchobhair (O’Connor), Ó Domhnaill (O’Donnell), and Ó Súilleabháin (O’Sullivan). Surnames starting with Mac or Mc feature Mac Cárthaigh (McCarthy), Mac Diarmada (McDermott), Mac Domhnaill (McDonnell), and Mac Lochlainn (McLaughlin). While ‘Mac’ is commonly anglicized as ‘Mc’, both prefixes are Irish in origin, with two-thirds of all ‘Mc’ surnames having Irish roots, though ‘Mac’ is more prevalent in Scotland and Ulster.

Different branches of families sharing the same surname sometimes adopted distinguishing epithets, which occasionally evolved into surnames themselves. For instance, the chief of the Ó Cearnaigh (Kearney) clan was known as An Sionnach (Fox), a name his descendants use today. Similar surnames are frequently found in Scotland due to the shared language and significant Irish migration in the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries.

In the Late Middle Ages, the Irish people were active traders across the European continent. They were distinguished from the English, who primarily used their own language or French, by their exclusive use of Latin abroad, a language “spoken by all educated people throughout Gaeldom.” The writer Seumas MacManus suggested that Christopher Columbus may have visited Ireland to gather information about western lands, and Irish names are reportedly on his crew roster, though other detailed studies dispute Irish or English involvement in the 1492 voyage.

An English report from 1515 indicated that the Irish people were structured into over sixty Gaelic lordships and thirty Anglo-Irish lordships, which the English termed “nation” or “country.” The Irish term “oireacht” encompassed both the territory and the people ruled by a lord, literally meaning an “assembly” where Brehons held courts on hills to arbitrate matters. The Tudor lawyer John Davies lauded the Irish’s love for “equal and indifferent (impartial) justice,” stating, “There is no people under the sun that doth love equal and indifferent (impartial) justice better than the Irish, or will rest better satisfied with the execution thereof, although it be against themselves, as they may have the protection and benefit of the law upon which just cause they do desire it.

These assemblies, according to another English commentator, included “all the scum of the country,” meaning both the laboring population and landowners. While the legal distinction between “free” and “unfree” elements of the Irish people was minimal, it was a profound social and economic reality. Social mobility often trended downwards due to economic and social pressures, with the ruling clan’s “expansion from the top downwards” continually displacing commoners to the margins of society.

Genealogy held paramount importance in this clan-based society, earning Ireland the rightful title of a “Nation of Annalists.” Various branches of Irish learning—including law, poetry, history, genealogy, and medicine—were traditionally associated with hereditary learned families. Notable poetic families included the Uí Dhálaigh (Daly) and the MacGrath, while Irish physicians, such as the O’Briens in Munster, were renowned in European courts.

Learning was not confined to these hereditary families, as exemplified by Cathal Mac Manus, a 15th-century diocesan priest who authored the Annals of Ulster. Other distinguished learned families included the Mic Aodhagáin and Clann Fhir Bhisigh, with the latter producing Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh, the 17th-century genealogist and compiler of the Leabhar na nGenealach.

The 16th-century Age of Discovery sparked English interest in colonizing Ireland under the Tudors. King Henry IV initiated “surrender and regrants,” but it was Catholic Queen Mary I of England who began the first plantations in Ireland in 1550, establishing a model for future English, and later British, imperial colonization. These initial plantation counties were named Philipstown (now Daingean) and Maryborough (now Portlaoise) by the English planters.

The Enterprise of Ulster, involving Shane O’Neill and Queen Elizabeth I, proved a failure. However, the subsequent Munster plantations saw some success, with a population of 4,000 in 1580 potentially growing to 16,000 by the 1620s. Following the Irish defeat in Ulster during the Nine Years’ War, King James I, who also reigned as James VI of Scotland, pursued new colonization efforts, fearing further rebellions.

Drawing from the Munster Plantations, King James I planted both English and Scottish settlers in the Ulster Plantations, predominantly in what is now Northern Ireland, marking the most successful colonization endeavor. These plantations introduced Tudor English settlers to Ireland, and the 17th-century Ulster Plantation specifically brought a significant number of Scottish, and fewer English and French Huguenot, colonists. Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, after defeating Irish rebels (1653–1658), also settled New English, forming the Protestant ascendancy.

The Enlightenment period in Ireland was marked by significant contributions from notable Irish scientists. The Anglo-Irish scientist Robert Boyle (1627–1691) is celebrated as the father of chemistry for his 1661 work, “The Sceptical Chymist.” Boyle, an atomist, is particularly known for Boyle’s Law. Rear Admiral Francis Beaufort (1774–1857), an Irish naval officer of Huguenot descent, developed the Beaufort scale for measuring wind force.

George Boole (1815–1864), the mathematician credited with inventing Boolean algebra, spent his later life in Cork. The 19th-century physicist George Stoney introduced the concept and name of the electron and was the uncle of another prominent physicist, George FitzGerald. These figures underscore Ireland’s role in scientific advancements during this era.

The Irish bardic system, along with Gaelic culture and learned classes, faced decline due to the plantations. Brian Mac Giolla Phádraig (c. 1580–1652) and Dáibhí Ó Bruadair (1625–1698) are considered among the last true bardic poets. Later Irish poets of the late 17th and 18th centuries, such as Séamas Dall Mac Cuarta and Seán Clárach Mac Domhnaill, transitioned to more modern dialects.

Despite the Penal laws, Irish Catholics continued to receive education in clandestine “hedgeschools.” Latin knowledge was surprisingly common among poor Irish mountaineers in the 17th century, used on special occasions, and cattle were even traded using Greek in County Kerry mountain markets, highlighting remarkable linguistic resilience.

For a comparatively small population of about 6 million, Ireland has made an immense contribution to literature, encompassing both Irish and English languages. Luminaries such as Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde, James Joyce, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett, W.B. Yeats, and Séamus Heaney are globally renowned writers, playwrights, and poets from Ireland, demonstrating the nation’s profound literary legacy.

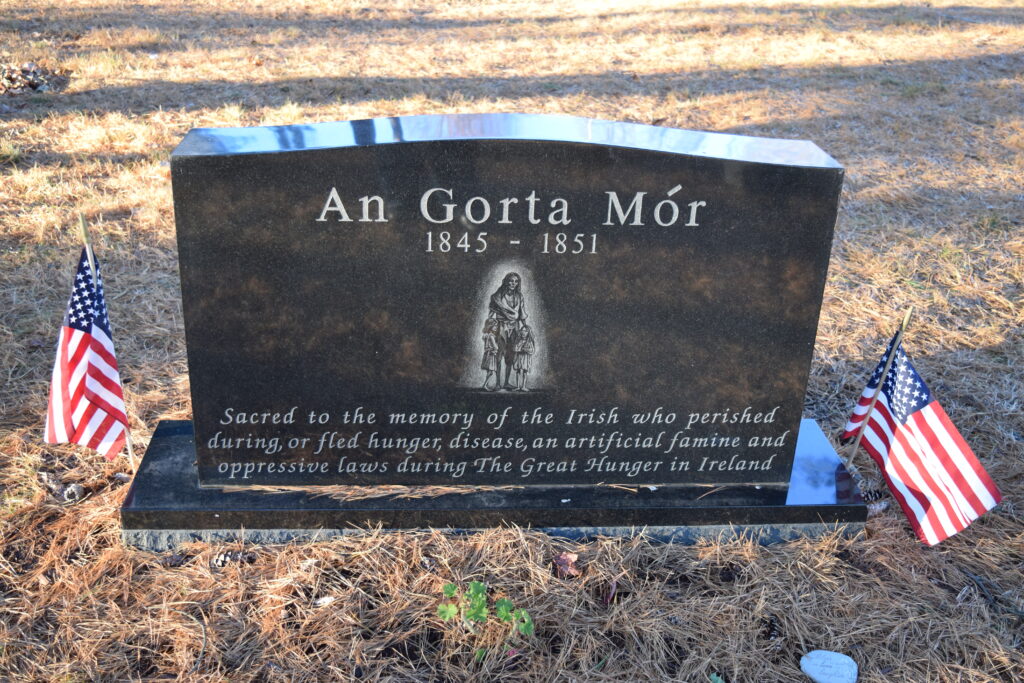

The 19th century in Ireland was indelibly marked by An Górta Mór, or “The Great Hunger,” the devastating Great Famine from 1845 to 1849. This catastrophe, reaching its peak in 1847, known as Black ’47, resulted in millions of Irish people dying or emigrating. The famine was precipitated by the potato blight, which infected the staple food of the impoverished Irish population, exacerbated by the British administration’s appropriation of other crops and livestock for its armies abroad.

The infected potatoes turned black, and starving people who attempted to eat them often vomited soon after. Despite the setting up of soup kitchens, their impact was minimal. The British government provided limited aid, notably sending raw corn, which became known as ‘Peel’s Brimstone’ after Prime Minister Robert Peel, yet many Irish were unfamiliar with cooking corn, leading to little improvement. Disease-ridden workhouses, plagued by cholera and tuberculosis, were established but also failed, with many dying upon arrival due to overwork and lack of food. Some contemporary British political figures reportedly viewed the famine as divine intervention intended to exterminate the majority of the native Irish population.

To escape the famine, Irish people emigrated en masse, primarily to the east coast of the United States, particularly Boston and New York, as well as to Liverpool in England, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Historical records indicate that a significant number of Irish emigrants to Australia were prisoners, with some committing crimes deliberately to be extradited, preferring penal transport to the hardships in their homeland. Emigrants endured horrific conditions on ‘Coffin Ships,’ so named for their high mortality rates from disease and starvation, as passengers were often treated as mere cargo.

Today, numerous statues and memorials in Dublin, New York, and other cities serve as solemn reminders of the famine’s devastation. The late-20th century song “The Fields of Athenry” stands as a poignant musical homage to those affected, frequently sung at national sporting events. The Great Famine remains one of the most significant events in Irish history, deeply ingrained in the nation’s identity and a major catalyst for Irish nationalism and subsequent movements for independence from British rule.

The 20th century brought pivotal changes, including the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), which culminated in the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the formation of the independent Irish Free State, now the Republic of Ireland, encompassing 26 of Ireland’s 32 traditional counties. The remaining six counties in the northeast continued as Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom.

Divisions between the two communities in Northern Ireland are largely rooted in religious, historical, and political differences, manifested as nationalism and unionism. Surveys conducted between 1989 and 1994 revealed that over 79% of Northern Irish Protestants identified as “British” or “Ulster,” with 3% or less identifying as “Irish.” In contrast, over 60% of Northern Irish Catholics identified as “Irish,” with 13% or less identifying as “British” or “Ulster.” A 1999 survey further refined these findings, showing 72% of Protestants considered themselves “British” and 2% “Irish,” while 68% of Catholics considered themselves “Irish” and 9% “British.” This survey also found strong feelings of “Britishness” among Protestants and “Irishness” among Catholics.

Regarding contemporary religious demographics, as of 2022, approximately 69.1% of the Republic of Ireland’s population, or 3.5 million people, identify as Catholic. In Northern Ireland, according to 2011 data, Protestants constitute about 41.6% of the population (with specific denominations including Presbyterian, Church of Ireland, Methodist, and other Christian groups), while approximately 40.8% identify as Catholic.

The 31st International Eucharistic Congress, held in Dublin in 1932, a year marking the presumed 1,500th anniversary of Saint Patrick’s arrival, drew about one-third of Ireland’s 3,171,697 Catholics. Time Magazine noted the Congress’s special theme as “the Faith of the Irish.” Similar massive crowds gathered for Pope John Paul II’s Mass in Phoenix Park in 1979, underscoring the enduring significance of faith.

While the majority of Irish people in the Republic of Ireland still identify as Catholic today, church attendance has markedly declined in recent decades. A similar decline is observed in Northern Ireland, where nearly 50% of the population is Protestant. The interplay of faith and Irish identity has been a longstanding concern, particularly for Catholics and Irish-Americans, raising complex questions about what truly defines an “Irishman.

Questions persist: Is it faith, or place of birth? Are Irish-Americans truly Irish? Who is “more Irish”—a Catholic Irishman like James Joyce, striving to escape his Catholicism and Irishness, or a Protestant Irishman such as Oscar Wilde, who ultimately embraced Catholicism? Or perhaps someone like C. S. Lewis, an Ulster Protestant, who moved towards a deeper understanding of it without fully crossing a threshold? These nuanced perspectives underscore the evolving and multifaceted nature of Irish identity, a subject of ongoing discussion and reflection among followers of nationalist ideologists like D. P. Moran and across the wider global Irish diaspora.

The St. Patrick’s Day parade in County Kerry, and the global spectacle of Irish dancers, are vivid modern expressions of an identity forged over millennia. From the ancient tales of the Milesians to the genetic markers of Bronze Age settlers, and through periods of scholarly brilliance, devastating famine, and political division, the Irish people have maintained a remarkable cultural continuity. Their customs, language, music, dance, and mythology continue to define them, even as their story expands to include a global diaspora of 50 to 80 million people. This enduring legacy is not merely a collection of facts but a living narrative, continually shaped by history, resilience, and a vibrant sense of self.

As Thomas Davis, the prominent Protestant Irish nationalist and founder of the Young Ireland movement, asserted, the Irish are fundamentally a Celtic nation. He estimated that five-sixths of the nation were either of Gaelic Irish origin or descended from returned Scottish Gaels, including many Ulster Scots, along with some descendants of pre-Gaelic populations, recognizing a deep, shared heritage that transcends specific historical periods and migrations. The collective journey of the Irish, from their earliest origins to their contemporary global presence, continues to be a compelling study in identity, adaptation, and unwavering cultural pride.