Have you ever wondered what people did before the invention of toilet paper? It’s one of those questions that might cross your mind while you’re perusing the aisle of your local supermarket, contemplating the myriad options for your bathroom needs. This seemingly trivial query actually unlocks a profound journey into the past, revealing the remarkable ingenuity of humanity in addressing one of its most fundamental and universal needs.

From the sprawling empires of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt to the bustling cities of medieval Europe, our ancestors developed an astonishing array of solutions for personal hygiene. These weren’t just crude improvisations; they were often culturally significant practices, deeply integrated into daily life, reflecting the resources available and the prevailing societal norms of their time. The story of what people used before toilet paper is a testament to human adaptability and creativity, illustrating how different civilizations approached the essential task of cleanliness.

As we embark on this exploration, we will peel back the layers of history to uncover the surprising and sometimes bizarre methods our forebears used to keep clean. Beyond mere curiosity, understanding the evolution of bathroom habits offers insights into the development of societies, the influence of culture and religion, and even the advancement of technology. So, let us delve into the nitty-gritty of what people did before the ubiquitous roll, emerging with a newfound appreciation for this humble modern convenience that so many now take for granted.

1. **Clay Tablets: Mesopotamian Ingenuity**In the fertile crescent of ancient Mesopotamia, a civilization renowned for its advancements in writing and administration, people utilized an unexpected material for personal hygiene: clay tablets. These ubiquitous items, central to their record-keeping and communication, found an additional, albeit less celebrated, purpose in the realm of the latrine. This adaptation speaks volumes about the remarkable resourcefulness of early societies, making practical use of readily available materials for daily needs. The choice underscores a fundamental principle of survival and convenience in an era far removed from modern amenities.

The practice of using clay tablets for wiping purposes highlights a profoundly pragmatic approach to hygiene in a time devoid of modern paper products. While the context does not elaborate on the specific preparation or comfort level of such a material, one can infer that their relatively smooth surfaces, once dried and perhaps softened through use, offered a functional if not entirely comfortable solution. This rudimentary method would have necessitated a different standard of personal comfort compared to what we expect today, prioritizing efficacy over luxury and immediate availability over plush softness.

This choice would have been significantly influenced by the widespread availability of clay as a natural resource in the region, fundamental to Mesopotamian life and industry. Clay was not only used for tablets but for construction, pottery, and various other essential items, making it an ever-present material in their daily lives. Its abundance meant that even a disposable application for hygiene would have been sustainable within their environmental context, reflecting a deeply integrated use of local resources that was both efficient and practical for the masses.

Moreover, this method offers a glimpse into the broader context of ancient hygiene, where cleanliness was often intertwined with spiritual purity, as noted in the historical overview provided. The selection of material would have been less about softness and more about the practical act of cleansing to maintain a basic level of purity. It powerfully illustrates how different cultures, even those with advanced capabilities in other areas like cuneiform, tailored their hygiene solutions to their unique environmental and technological circumstances, highlighting the sheer adaptability of humankind in the face of nature’s call.

2. **Smooth Stones and Broken Pottery: Egyptian Solutions**Across the ancient world, in the venerable civilization of Egypt, a distinct set of materials was favored for personal hygiene, particularly by the elite classes. Instead of clay tablets, as seen in Mesopotamia, the privileged Egyptians opted for smooth stones or carefully selected fragments of broken pottery. This discerning choice reflects a society that valued order and, for its affluent members, perhaps a degree of refinement even in the most private of acts, demonstrating a subtle yet significant pursuit of comfort and aesthetic considerations in their personal care.

The selection of smooth stones implies a preference for a non-abrasive surface, suggesting an early consideration for comfort that might have been less prevalent with rougher alternatives. These stones would have been collected from riverbeds or desert landscapes, naturally polished by the elements to achieve their desired texture. The deliberate search for such smooth materials indicates an attention to detail in personal care, transcending mere necessity to encompass a measure of dignity even in such an intimate practice.

Similarly, broken pottery fragments, while initially sounding harsh, would likely have been chosen for their smooth, rounded edges and perhaps concave shapes, making them more suitable than jagged shards. It is plausible that these fragments were intentionally smoothed or prepared for this specific, delicate application, reflecting a careful craftsmanship applied even to disposable items. This practice again demonstrates a keen adaptation to the local environment and its resources, transforming what might otherwise be considered refuse into a functional hygiene tool.

These materials were readily available across the Egyptian landscape, making them a sustainable and accessible option for those who could procure them. The emphasis on ‘smooth’ options, especially among the elite, hints at an underlying pursuit of both comfort and dignity in personal care. This class-based distinction in hygiene materials underscores the socioeconomic stratification present in ancient Egypt, where even the most intimate aspects of daily life were influenced by wealth and status, providing a clear marker of social standing.

3. **The Xylospongium: Roman Communal Hygiene**Venturing into the classical world of Greece and Rome, we encounter a truly distinct and, to modern sensibilities, somewhat startling innovation: the “xylospongium.” This sophisticated tool consisted of a sponge affixed to a stick, a seemingly simple invention that revolutionized communal hygiene in public latrines. The very existence of such a specialized implement speaks to a society that considered personal cleansing with a certain level of systematic design and shared resources, which contrasts sharply with individualistic modern practices.

The Romans, in particular, embraced this concept, referring to their version as a “tersorium,” literally meaning “a wiping thing.” They cleaned their behinds with these sea sponges attached to a stick, and crucially, a gutter supplied clean flowing water. This allowed users to dip the sponges in, ensuring a rinse and perhaps a level of reusability, though the communal aspect certainly challenges modern notions of sanitation and personal ownership. The provision of flowing water indicates an advanced understanding of waste management and a desire for some form of cleanliness.

Remarkably, the context notes that Romans “liked to move their bowels in comfort.” The tersorium, described as a “soft, gentle tool,” undoubtedly contributed to this desired comfort, standing in stark contrast to harsher, dry wiping methods used by other cultures or earlier periods. This focus on comfort, even in a communal setting, highlights a particular Roman value for a degree of ease and well-being in their daily lives, including their most private moments.

The public nature of Roman latrines, where toilet seats were close together with little historical evidence of separate facilities for men and women, suggests a different cultural understanding of privacy. Loose togas provided “some modicum of privacy,” indicating a practical adaptation to communal settings. Yet the shared use of the xylospongium remains a fascinating testament to their unique communal hygiene practices, reflecting a collective approach to necessities that might seem startlingly unhygienic by contemporary standards but was a sophisticated solution for their time.

4. **Hay, Straw, and Wool: Medieval Europe’s Varied Wipes**As we transition to medieval Europe, a period often characterized by its stark social stratification, hygiene practices mirrored these profound divides. For the common people, who often lacked access to finer materials, practicality dictated their choices for personal cleansing. They frequently resorted to readily available agricultural byproducts such as hay and straw. These fibrous materials, while perhaps coarse and less than ideal in terms of comfort, were abundant and served the basic function of wiping, embodying a pragmatic approach to daily necessities.

The pervasive use of hay and straw reflects the predominantly agrarian nature of medieval society, where these materials were plentiful and easily gathered after harvests. Their effectiveness would have varied greatly depending on the specific type and dryness, but their sheer accessibility made them a default, indispensable option for the majority of the population. This reliance on the immediate environment for such personal needs paints a vivid picture of medieval life, far removed from modern conveniences and the widespread availability of specialized hygiene products.

This practice contrasts sharply with the experiences of wealthier individuals in Europe, who enjoyed a more comfortable and refined approach to personal hygiene. Unlike the common folk, the affluent could afford alternatives that prioritized comfort and softness, highlighting the significant disparities in living standards. Their resources allowed them to transcend the limitations faced by the broader population, providing a glimpse into the luxuries afforded by status, even for something as fundamental as post-bathroom cleansing.

For the affluent, wool emerged as a preferred alternative, often in the form of rags and scraps of cloth. Wool, being inherently softer, more pliable, and more luxurious than the rough hay or straw, provided a gentler option for wiping. This distinction underscores how socioeconomic factors profoundly influenced personal hygiene, transforming a basic human need into a clear indicator of wealth and social standing. The quality and comfort of one’s cleansing materials were indeed a luxury during this historical period, separating the privileged from the commoners.

5. **Leaves and Other Plant Materials: Nature’s Gentle Touch**Across diverse cultures and geographical regions, particularly where natural environments were abundant, leaves and other readily available plant materials served as widespread solutions for personal hygiene. This reliance on flora speaks to humanity’s innate ability to utilize its immediate surroundings, finding practical applications for nature’s bounty for millennia. The specific choice of plant material was often dictated by local ecology, favoring species that offered suitable textures and properties, demonstrating a deep, empirical understanding of their environment.

In forested areas, for example, indigenous populations, including numerous Native American tribes, had access to a wealth of plant materials. They judiciously selected large, soft leaves from certain types of trees or bushes, valuing their gentle texture for wiping purposes. This discerning choice suggests an inherent understanding of comfort and effectiveness, as they actively avoided harsh or irritating foliage. Such thoughtful practices were not unique to Native American communities but were also adopted by colonial settlers, who frequently resorted to leaves or corn cobs when manufactured options were non-existent.

Beyond mere tactile qualities, some tribes were known to utilize specific plants that possessed innate antibacterial properties. This remarkable foresight, predating modern scientific understanding of microscopic organisms and their effects, indicates a sophisticated, empirical knowledge of their local pharmacopeia. These carefully chosen plants would have contributed not only to physical cleansing but also potentially to the promotion of overall hygiene and the prevention of infection, highlighting an early, intuitive form of natural antiseptic use among these communities.

The enduring legacy of using leaves reflects a simple yet profoundly effective method that transcended many cultures and time periods. It is a testament to human resourcefulness and the ability to find practical solutions in the natural world. This ancestral practice highlights a period when personal care was intrinsically linked to the environment, fostering a deeper connection to the land and its varied offerings for daily necessities, a connection that is often overlooked in our modern, sanitized world.

6. **Moss: The Softness of the Forest Floor**In regions where lush, green environments thrived, particularly in areas with abundant moss, this soft and spongy plant material emerged as another remarkably effective natural alternative for personal hygiene. From medieval Europeans making do with what was at hand, to various Native American tribes, particularly in places like the Pacific Northwest, moss provided a gentle and surprisingly absorbent solution for cleansing. Its widespread availability in certain biomes made it a highly practical and sustainable choice for communities living close to nature.

The inherent appeal of moss for personal hygiene lay in its distinctive tactile qualities. Described explicitly as “soft” and “spongy,” it offered a degree of comfort and pliability that many coarser materials like straw or rough leaves simply could not. This natural absorbency would have been a crucial functional factor, making it an efficient natural wipe for removing waste. The unique properties of moss therefore positioned it as a premium natural option in comparison to other raw materials available in the wilderness, valued for its gentle effectiveness.

For Native Americans in particular, the utilization of moss was not merely a last resort but an integrated and intelligent part of their resourceful approach to living harmoniously with their environment. Its gentle nature and absorbent qualities made it a preferred choice, reflecting a deep respect for and an intricate understanding of the natural world and its beneficial offerings. This demonstrates an ecological awareness that enabled practical solutions for everyday needs, born from generations of observation and tradition.

The widespread use of moss underscores the sophisticated and intimate relationship these communities cultivated with their surroundings, meticulously extracting practical solutions from the very landscape they inhabited for countless generations. It is a powerful example of how natural resources, when understood and respected, could provide for essential human needs, long before the advent of manufactured goods and the modern separation of humanity from its natural origins. It speaks to a deep ancestral wisdom that utilized the earth’s gifts for comfort and cleanliness.

7. **Corn Cobs: Nature’s Rural Scrubber**In many agricultural societies across North America, especially where corn (maize) reigned as a staple crop, an ingenious and readily available solution for personal hygiene emerged: the dried corn cob. After the kernels were harvested for sustenance, the remaining cobs, often discarded or repurposed for other trivial tasks, found a surprisingly effective role in the outhouse. This practical adaptation showcases the deep resourcefulness of indigenous populations and early American settlers, transforming an agricultural byproduct into a functional tool for daily cleanliness. The very abundance of corn made cobs an ever-present, sustainable option for rural agrarian communities, highlighting a direct connection between agricultural cycles and personal care. The simplicity of this solution, born from necessity, speaks volumes about the ingenuity that flourished in a pre-industrial world.

The efficacy of the corn cob for wiping purposes lay in its unique structural properties. While it might sound rudimentary or even harsh to modern ears accustomed to plush paper, the relatively smooth yet textured surface of a dried cob offered a viable means of cleansing. The myriad grooves and indentations that naturally characterize a corn cob were, in fact, quite efficient at trapping and removing any remaining fecal matter, functioning with a surprising degree of thoroughness. According to Farmers’ Almanac, the corncob worked ‘by turning on its axis to clean the region,’ illustrating a hands-on, almost mechanical approach to hygiene that maximized its natural form for effective cleaning. This method, while perhaps not offering the softness of modern paper, prioritized utility and availability.

This widespread practice was not merely a last resort but a popular choice, particularly among Native Americans and colonial settlers throughout North America. The sheer convenience of insertion and the surprisingly soft feel when dried contributed to its favorability. Its availability during the 1776 period, as noted in historical inquiries, meant that ‘most colonial people used leaves or corn cobs. Yes, corn cobs!’ This direct historical reference underscores its significance. The enduring presence of this method is even noted in some outhouses in western US states today, where corn cobs are still utilized, serving as a tangible link to historical hygiene practices and a testament to their enduring practicality in certain rural contexts.

The corn cob, therefore, stands as a powerful symbol of human adaptability, transforming a common crop into an indispensable personal care item. It reflects the intimate relationship between people and their immediate environment, where every part of a harvested plant could be given a second, essential purpose. This resourcefulness, driven by the realities of agrarian life and limited access to manufactured goods, shaped daily habits and contributed to a unique chapter in the broader history of human hygiene, showcasing how communities made do with what was abundantly at hand for generations.

8. **Water: The Universal Cleanser in Indigenous Cultures**Across countless indigenous cultures globally, and particularly among Native American tribes, water held a profound and central role in personal hygiene practices, often superseding dry wiping materials. Rather than relying on physical implements for post-bathroom cleansing, individuals would frequently purify themselves with water, embracing a method that was both effective and deeply rooted in cultural and spiritual beliefs. This practice involved either washing directly with water from a nearby stream or river, or using a vessel to pour water for a thorough rinsing, embodying a holistic approach to cleanliness that emphasized natural elements and a deep respect for the environment.

The choice of water for cleansing extended beyond mere practicality; it resonated with broader cultural values that often intertwined physical purity with spiritual well-being. Many indigenous traditions viewed water as a sacred element, capable of cleansing not only the body but also the spirit. This philosophical connection elevated the act of post-bathroom cleansing from a simple bodily function to a ritualistic practice, ensuring a state of both physical and spiritual readiness for daily life or ceremonial participation. The refreshing sensation provided by water also contributed to a feeling of complete cleanliness that dry methods often could not achieve, offering a deeper sense of personal renewal.

This method stands in stark contrast to many dry wiping alternatives prevalent in other historical societies, offering a more hygienic and, arguably, more comfortable experience. The constant flow or dedicated application of water ensured a more thorough removal of waste, minimizing residual matter and promoting better overall health. This was especially important in communities where understanding of microscopic organisms like germs and bacteria was not yet scientific, but empirical knowledge of cleanliness for health was strong. The widespread adoption of water cleansing highlights a sophisticated, intuitive understanding of hygiene among indigenous communities, demonstrating a preference for methods that were both environmentally integrated and inherently effective, long before the advent of modern plumbing systems.

Such practices illustrate a lifestyle deeply attuned to the natural world. Indigenous peoples often lived in close proximity to natural water sources, making this form of hygiene both convenient and sustainable. The act of cleansing with water was a daily ritual, as exemplified by the ancient Indians who traced accountable daily bathing rituals with three daily baths and washing, emphasizing a consistent commitment to personal purity. This enduring tradition of water-based hygiene underscores a profound cultural perspective on cleanliness, shaping habits and beliefs across generations, and influencing everything from personal habits to communal well-being.

9. **Snow: Cleansing in Cold Climates**In the frigid expanses of colder climates, where water sources frequently froze over or became scarce during harsh winters, indigenous communities adapted their hygiene practices with remarkable ingenuity, turning to snow as a natural alternative for cleansing. This seemingly counterintuitive choice speaks volumes about human resourcefulness in extreme environments, demonstrating how nature’s challenges can inspire unique and effective solutions for fundamental needs. The transformative power of a frozen landscape provided an unexpected, yet potent, tool for personal cleanliness when conventional liquid water was inaccessible, forcing communities to innovate with the elements at hand.

The effectiveness of snow for post-bathroom hygiene stemmed from a combination of its unique physical properties. While it might appear soft, snow possesses a naturally abrasive texture, capable of effectively removing waste. This gentle exfoliation, combined with its intensely cold temperature, offered a thorough and invigorating clean feeling. The cold not only helped to contract skin and provide a refreshing sensation but also served as a natural antiseptic, potentially reducing the presence of bacteria in a way that dry materials could not. This practical solution harnessed the very elements of a challenging environment, turning a perceived limitation into a functional advantage for hygiene.

This innovative use of snow underscores the deep connection and empirical knowledge that indigenous peoples cultivated with their natural surroundings. It wasn’t a random improvisation but a calculated adaptation, born from generations of living harmoniously and resourcefully with the land. Such practices highlight a profound ecological awareness, where every aspect of the environment, even seemingly harsh ones like snow and ice, was understood for its potential utility. The choice of snow for cleansing is a powerful testament to the resilience and inventive spirit of cultures that thrived by meticulously understanding and utilizing the earth’s varied offerings for comfort and cleanliness, showcasing an extraordinary level of adaptation.

The application of snow as a hygiene tool reveals a sophisticated interplay between environmental conditions and cultural practices. It required a certain robustness and adaptability from individuals, transforming a seemingly uncomfortable act into a practical and refreshing one. This method reflects a historical period where daily necessities were intimately linked to the immediate natural world, fostering a practical wisdom about how to survive and thrive even in the most challenging geographical settings, a stark contrast to modern indoor amenities.

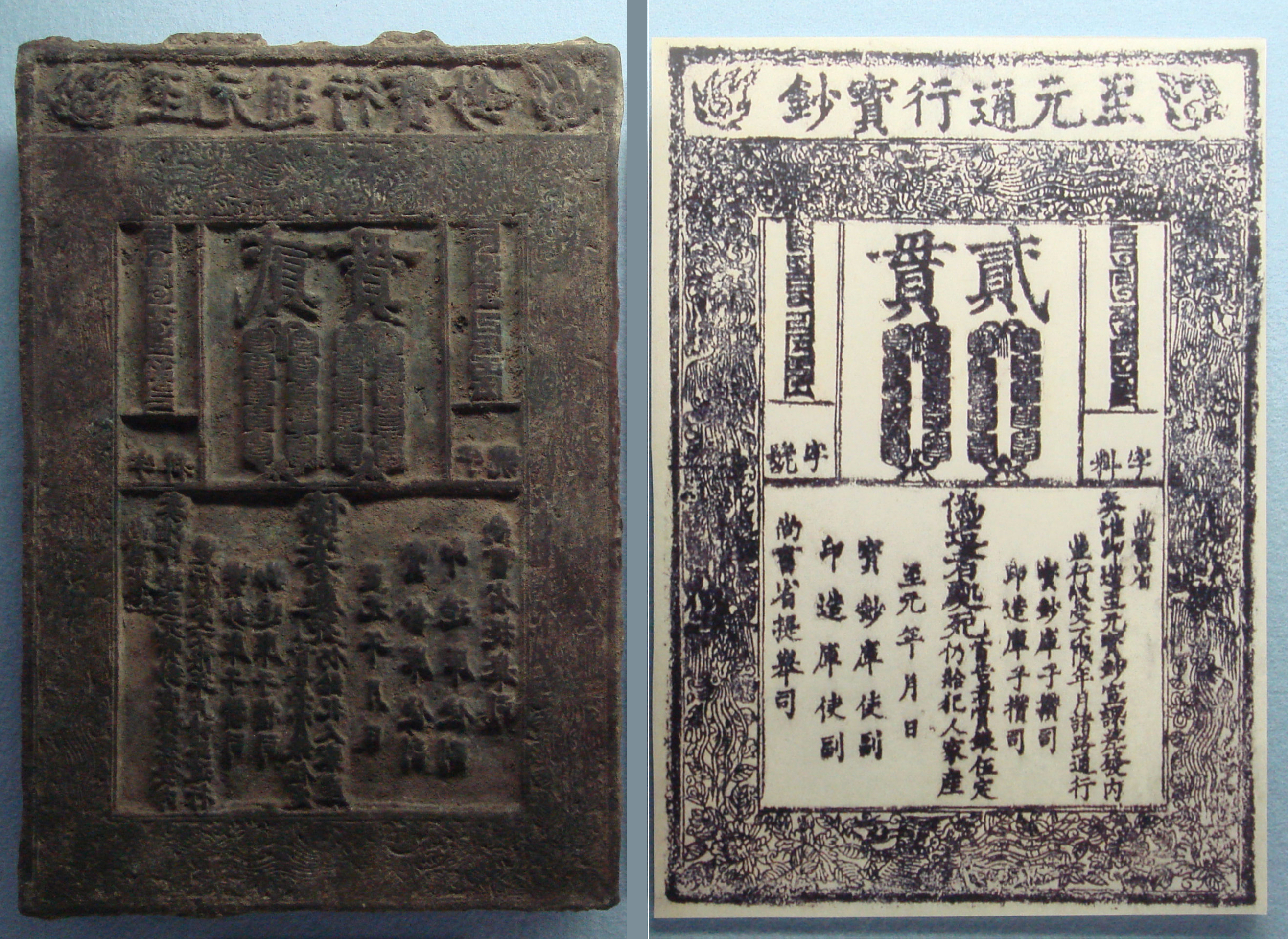

10. **Early Paper Innovations: China’s Pioneering Role**While modern toilet paper became widely available only in the 19th century, the concept of paper-based hygiene has a much longer and richer history, with its origins firmly rooted in ancient China. This remarkable civilization, renowned for its groundbreaking inventions including papermaking, was also the first to embrace paper for personal cleansing, centuries before the practice became common elsewhere. The ‘Chinese invention of paper, which eventually found its way into the bathroom,’ marks a significant turning point in the history of hygiene, laying the groundwork for the modern convenience we know today and showcasing China’s enduring legacy in technological advancement.

Historical records indicate that as early as the 2nd century BC, and certainly by the 6th century AD, paper was being used for wiping in China. This adoption was a testament to the advanced papermaking techniques developed in the region, which allowed for the production of paper in sufficient quantities and with suitable properties for such a utilitarian purpose. Unlike the rougher natural materials or communal sponges used in other parts of the world, paper offered a singular, disposable, and relatively soft option, signifying a leap forward in personal comfort and sanitation standards that would take hundreds of years to reach the Western world.

The widespread use of paper for hygiene in China reflects a society that valued sophistication and practicality, even in mundane daily routines. As paper became more abundant and less expensive, its application broadened from scholarly and administrative uses to include more essential personal needs. This early embrace of paper as a personal hygiene tool showcases Chinese ingenuity not just in invention, but also in the practical application of new technologies for improving daily life, demonstrating a foresight that predated similar developments in other civilizations by hundreds of years. The sheer scale of its production and adoption for this purpose truly set China apart.

The Chinese contribution to hygiene extends beyond just the material itself. The understanding of how to produce paper on a large scale and its integration into daily life for practical, sanitary purposes highlights a societal priority for cleanliness and order. This ancient practice serves as a powerful reminder of humanity’s continuous quest for comfort and efficiency, driving innovation that profoundly impacts the most intimate aspects of human existence, proving that even the simplest amenities have complex historical roots.

11. **Repurposed Printed Materials: Early American Settlers’ Ingenuity**As European settlers expanded across North America, establishing new communities and adapting to frontier life, they often found themselves without the familiar conveniences of their homelands. In this environment, long before the commercial availability of toilet paper, they demonstrated remarkable ingenuity by adapting readily available materials for personal hygiene. Among the most common and resourceful solutions were ‘old newspapers and catalogs’ and ‘magazines,’ which became a staple for wiping in the 1700s and beyond, as paper became more prominent and expendable. This practical recycling of printed matter highlights a period where every resource was valued and given multiple uses out of necessity.

The widespread use of these repurposed printed materials was born out of necessity and practicality in colonial American households. Pioneers, who might have initially used natural elements like leaves, corn cobs, or seashells, quickly recognized the utility of paper as it became more common. Newspapers and catalogs, once read for information, offered a surface that was soft enough for the purpose and were, crucially, abundant and considered expendable, making them an ideal, low-cost alternative. The rough texture of the newsprint, while not luxurious, was effective for cleansing, and the sheer volume of such materials ensured a continuous supply in many households, especially those receiving regular deliveries.

This practice highlights a significant shift in hygiene habits tied to the rise of print media and consumer culture in America. As information and advertising spread, so did the availability of paper, transforming what was once a medium solely for communication into a tool for personal care. This cultural evolution is starkly illustrated by the historical detail that ‘In the 1700s, colonial Americans began using old newspapers and catalogs to wipe,’ even imagining the Founding Fathers, after signing the Declaration of Independence, resorting to dried corn cobs or newspapers. This adaptation truly encapsulates the resourcefulness of the era.

The transition from natural items to printed paper reflects the changing landscape of American life, showcasing how settlers creatively adapted existing resources to meet fundamental needs. This innovative approach to personal hygiene, driven by the practicalities of frontier living and the increasing ubiquity of paper, ultimately paved the way for the eventual invention and widespread adoption of mass-produced toilet paper, illustrating the continuous human drive for convenience and improved sanitation in all aspects of life.

**Conclusion**

The history of toilet paper alternatives offers a fascinating glimpse into the ingenuity and resourcefulness of humanity throughout the ages. From ancient civilizations to modern innovations, the quest for cleanliness and comfort has driven us to explore new technologies and adapt to changing cultural norms. As we reflect on the evolution of bathroom hygiene, it’s clear that our understanding of cleanliness is deeply rooted in cultural, religious, and socioeconomic factors.

By examining the historical, cultural, and technological dimensions of toilet paper alternatives, we gain a deeper appreciation for the role of hygiene in shaping human societies. From clay tablets to bamboo toilet paper, the journey of bathroom hygiene is a testament to our resilience and adaptability in the face of nature’s call. As we look to the future, let us continue to innovate and explore sustainable solutions for maintaining cleanliness and promoting public health for generations to come.