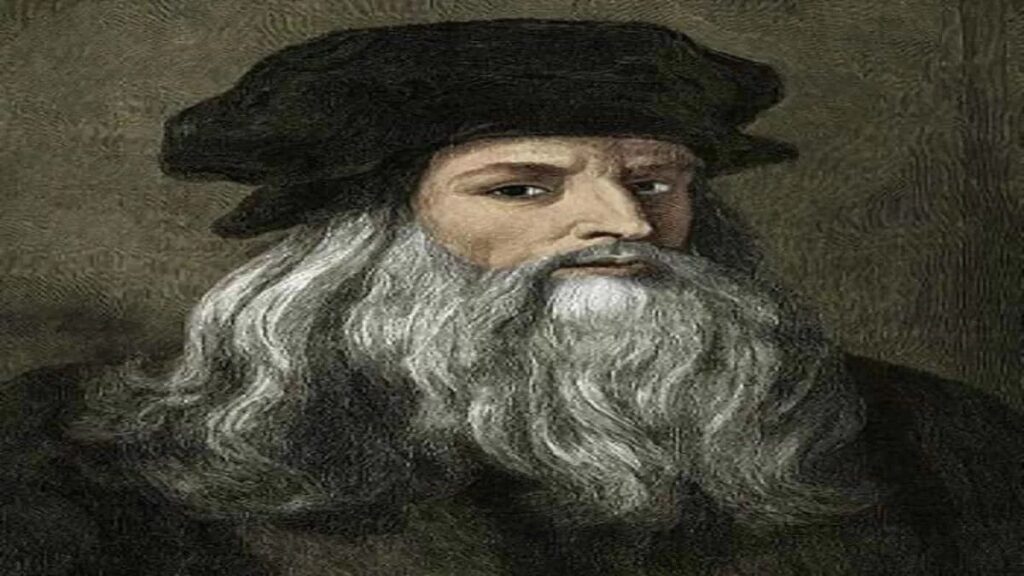

In the annals of human history, few names resonate with the sheer breadth of genius and creative output as profoundly as Leonardo da Vinci. More than just a painter whose works adorn the most prestigious galleries, Leonardo was a titan of the High Renaissance, a true polymath whose insatiable curiosity led him to master disparate fields ranging from art and architecture to engineering and anatomy. His notebooks, brimming with observations and inventions, offer an unparalleled glimpse into the mind of a man who was, truly, ahead of his time, making him an enduring figure of fascination and admiration across centuries.

His fame, initially rooted in his extraordinary achievements as a painter, has expanded exponentially over time to encompass the staggering diversity of his interests and his empirical approach to understanding the world. He is widely regarded as a genius who not only epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal but also laid foundational groundwork for scientific thought that would influence generations. His collective works and relentless pursuit of knowledge represent a contribution to later generations of artists matched only by that of his younger contemporary, Michelangelo.

This in-depth exploration invites us on a journey through the formative years and groundbreaking artistic periods of Leonardo da Vinci, tracing his remarkable trajectory from humble beginnings to becoming a revered master. We will peel back the layers of myth and historical account to understand the man behind the masterpieces, examining his education, his pivotal commissions, and the innovative spirit that defined his earliest triumphs. Prepare to delve into the intricate tapestry of a life that forever altered the course of art and intellectual endeavor.

1. **The Polymathic Genius: A Renaissance Ideal Embodied**Leonardo da Vinci, born Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, was an Italian polymath active across an astonishing array of disciplines during the High Renaissance. The context describes him as a “painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect.” This diverse engagement wasn’t merely a hobbyist’s dabbling; in each field, Leonardo made significant contributions, showcasing a mind unconstrained by conventional boundaries and driven by an unparalleled desire to understand the world in its entirety.

His legacy, beyond the iconic canvases, is profoundly shaped by the meticulous records he kept in his notebooks. These extensive volumes contain drawings and notes on subjects as varied as “anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, painting, and palaeontology.” They reveal a thinker deeply committed to empirical observation and systematic inquiry, principles that were foundational to the nascent scientific revolution yet to fully unfold. This spirit of inquiry firmly established him as a pioneer of scientific methodology.

Leonardo’s capacity to synthesize artistic expression with scientific investigation allowed him to imbue his art with an unprecedented realism and depth. His detailed understanding of light, human anatomy, botany, and geology, derived from direct observation and dissection, informed his painting techniques. This holistic approach is why he is so often regarded as a figure who “epitomised the Renaissance humanist ideal,” embodying the era’s belief in human potential and the integration of diverse forms of knowledge.

His influence was not just immediate but profoundly long-lasting. Since his death in 1519, “there has not been a time where his achievements, diverse interests, personal life, and empirical thinking have failed to incite interest and admiration, making him a frequent namesake and subject in culture.” His ability to seamlessly transition between art and science, always with an eye for innovation and truth, truly set him apart as a universal genius.

Read more about: Unveiling Leonardo da Vinci: A Renaissance Titan’s Enduring Legacy Across Art, Science, and Engineering

2. **Birth and Early Years: Humble Beginnings in Vinci**Leonardo’s story began on April 15, 1452, in, or near, the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, Italy, approximately 20 miles from Florence. His full name, “Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci,” literally translates to “Leonardo, son of ser Piero from Vinci,” clearly indicating his birthplace rather than a family name. This detail underscores his roots in a specific locale, though the exact site of his birth remains a subject of traditional accounts and historical speculation, with Anchiano, a country hamlet, often cited due to its privacy suitable for an illegitimate birth, or possibly a house in Florence.

He was born out of wedlock, a circumstance of considerable social impact in 15th-century Italy. His father was Piero da Vinci, a successful Florentine legal notary, while his mother was Caterina di Meo Lippi, described as being from the lower class. Both his parents married separately the year after his birth, illustrating the societal norms of the time. Caterina, who later appears simply as “Caterina” or “Catelina” in Leonardo’s notes, is commonly identified as Caterina Buti del Vacca, who married a local artisan.

For much of his early childhood, tax records indicate that by at least 1457, Leonardo lived in the household of his paternal grandfather, Antonio da Vinci. It is also believed he spent his initial years in the care of his mother in Vinci, either in Anchiano or Campo Zeppi. He is thought to have been particularly close to his uncle, Francesco da Vinci, while his father was likely occupied with his successful notarial career in Florence.

Despite his father’s prosperous lineage of notaries, Leonardo received only a basic and informal education, covering “vernacular writing, reading, and mathematics.” This unconventional path, often attributed to the early recognition of his prodigious artistic talents, meant his family opted to nurture his gifts in a practical rather than purely academic setting. This focus would prove instrumental in shaping his hands-on, empirical approach to all his later endeavors.

Read more about: Legends of the Asphalt: A Deep Dive into America’s Most Influential Automotive Icons

3. **The Crucible of Creativity: Apprenticeship with Andrea del Verrocchio**The mid-1460s marked a pivotal turning point in young Leonardo’s life as his family relocated to Florence, a city then vibrant with Christian Humanist thought and culture. Around the age of 14, he entered the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio as a “garzone,” or studio boy. Verrocchio, at the time, was renowned as the leading Florentine painter and sculptor, and his studio served as a bustling hub of artistic innovation and technical training.

Leonardo formally became an apprentice by the age of 17, embarking on a rigorous seven-year training period. This apprenticeship exposed him to an incredibly broad spectrum of skills, far beyond mere painting. The context details his theoretical training alongside practical applications in “drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and woodwork,” as well as the fundamental artistic skills of “drawing, painting, sculpting, and modelling.” This comprehensive education was undoubtedly crucial in fostering his polymathic capabilities.

Verrocchio’s workshop was also a melting pot of talent, attracting and nurturing other future masters of the Renaissance, including “Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and Lorenzo di Credi.” Leonardo’s interactions with these contemporaries, as well as the rich artistic environment of Florence, which showcased the works of Donatello, Masaccio, and Ghiberti, deeply influenced his artistic development. He was exposed to detailed studies of perspective by Piero della Francesca and the theoretical writings of Leon Battista Alberti, which had a profound effect on his subsequent observations and artworks.

Perhaps the most famous anecdote from this period, as recounted by Vasari, involves Leonardo’s collaboration with Verrocchio on *The Baptism of Christ* (c. 1472–1475). Leonardo reputedly painted a young angel with such superior skill that Verrocchio was said to have laid down his brush, never to paint again—a claim likely apocryphal but illustrative of Leonardo’s burgeoning talent. His innovative use of oil paint in sections of the work further highlighted his unique approach and technical prowess, foreshadowing the masterpieces yet to come.

Read more about: Unveiling Leonardo da Vinci: A Renaissance Titan’s Enduring Legacy Across Art, Science, and Engineering

4. **First Florentine Period: Emergence of an Independent Master**By 1472, at the age of 20, Leonardo had achieved the significant milestone of qualifying as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the esteemed guild for artists and doctors of medicine. Despite this professional independence and his father setting him up in his own workshop, his deep attachment to Verrocchio endured, leading him to continue collaborating and living with his former master. This period marked his transition from apprentice to an artist capable of securing his own commissions.

His earliest known dated work, a 1473 pen-and-ink drawing of the Arno valley, demonstrates his early fascination with landscapes and natural phenomena. Vasari even credits the young Leonardo with the innovative suggestion of making the Arno river a navigable channel between Florence and Pisa, revealing an early spark of his engineering mind even in his artistic youth. This blend of artistic observation and practical problem-solving was a hallmark of his approach.

In January 1478, Leonardo received his first independent commission: an altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in the Florentine town hall, the Palazzo della Signoria. This commission was a clear indication of his recognized independence from Verrocchio’s studio. Further consolidating his rising reputation, he received another significant commission in March 1481 from the monks of San Donato in Scopeto for *The Adoration of the Magi*.

However, neither of these initial Florentine commissions were brought to completion. This pattern, a recurring theme in Leonardo’s career, arose as he seized a new opportunity. He abandoned these projects when he offered his services to Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. His letter to Sforza eloquently detailed his diverse capabilities in engineering and weapon design, almost as an afterthought mentioning his painting skills, signaling his versatile ambitions beyond Florence’s artistic circles. During this period, Leonardo also frequented the Platonic Academy of the Medici, associating with leading humanist philosophers and poets, further enriching his intellectual breadth.

Read more about: Unveiling Leonardo da Vinci: A Renaissance Titan’s Enduring Legacy Across Art, Science, and Engineering

5. **Milanese Grandeur: Service to Ludovico Sforza**Leonardo’s relocation to Milan in approximately 1482 marked a significant new chapter, placing him in the service of Ludovico Sforza, a powerful and ambitious ruler. He remained in Milan until 1499, a period during which he produced some of his most profound artistic and engineering endeavors. His initial introduction to Sforza was as an ambassador from Lorenzo de’ Medici, bringing with him a silver string instrument shaped like a horse’s head, demonstrating his unique blend of artistic and mechanical flair.

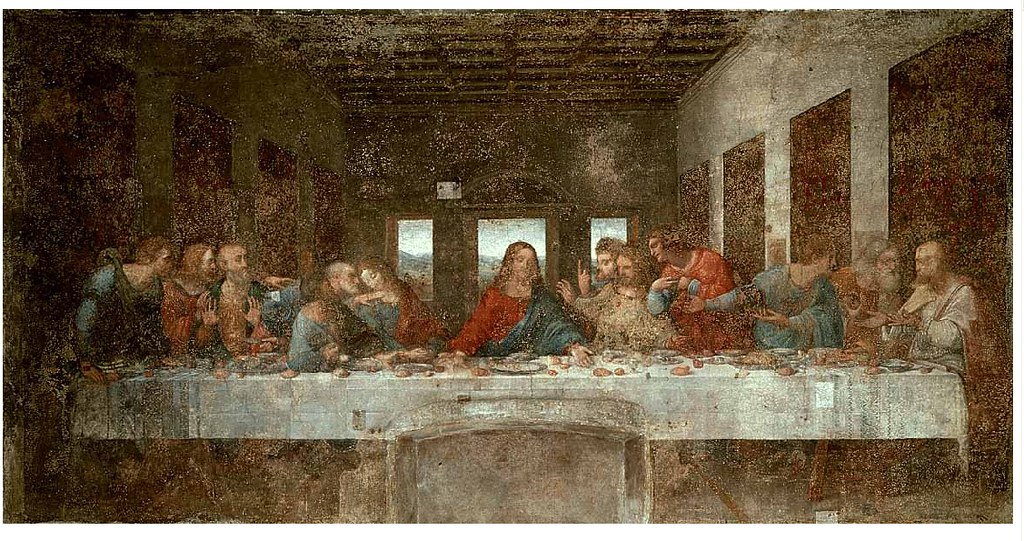

Among his most notable commissions during this Milanese period were two monumental paintings: *Virgin of the Rocks* for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and the iconic *The Last Supper* for the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. These works solidified his reputation as a master painter capable of innovative compositions and profound emotional depth. Beyond painting, Leonardo was engaged in a myriad of projects for Sforza, reflecting the duke’s appreciation for his diverse talents.

His tasks included the elaborate preparation of floats and pageants for special occasions, showcasing his ingenuity in mechanical design and theatrical staging. He also contributed to major architectural projects, providing a drawing and wooden model for a competition to design the cupola for Milan Cathedral. Perhaps the most ambitious of these non-painting commissions was the model for a colossal equestrian monument dedicated to Ludovico’s predecessor, Francesco Sforza, which became known as the *Gran Cavallo*.

This grand monument was envisioned to surpass in size the existing large equestrian statues of the Renaissance, Donatello’s *Gattamelata* and Verrocchio’s *Bartolomeo Colleoni*. Leonardo completed a full-scale clay model for the horse and meticulously planned its casting. However, the dream of casting the bronze behemoth was tragically cut short in November 1494 when Ludovico diverted the metal for cannons to defend Milan against the invasion of Charles VIII of France, leaving one of Leonardo’s most ambitious sculptural projects unfinished.

6. **Artistic Masterpieces: The Last Supper and its Innovations**Leonardo’s most renowned painting from his first Milanese period, indeed one of the most famous works of art in history, is *The Last Supper*. Commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, this fresco, completed around 1492–1498, captures a profoundly dramatic moment: Jesus’s declaration, “one of you will betray me,” and the resulting consternation among his disciples. Leonardo masterfully depicted the individual reactions of each apostle, revealing their distinct personalities and emotional turmoil.

The creation of *The Last Supper* was a painstaking process, as observed by the writer Matteo Bandello, who noted Leonardo’s erratic work habits—sometimes painting from dawn till dusk, then leaving the work untouched for days. This often exasperated the convent’s prior, leading to Ludovico Sforza’s intervention. Vasari even recounts a legendary tale where Leonardo, struggling to depict the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas, jokingly suggested using the prior as his model for Judas, a testament to his dry wit and deep immersion in the psychological aspects of his subjects.

Despite the painting being acclaimed as a “masterpiece of design and characterisation” upon its completion, it quickly began to deteriorate. Leonardo, eschewing the durable traditional fresco technique, chose to experiment with tempera over a ground primarily composed of gesso. This experimental method, while allowing for greater detail and subtle blending (a characteristic of his *sfumato* technique), proved disastrous for its longevity, making the surface susceptible to mould and flaking. Within a hundred years, it was described by one viewer as “completely ruined.”

Despite its rapid deterioration, *The Last Supper* has remained one of the most reproduced works of art, inspiring countless copies across various mediums. Its innovative composition, particularly the way Leonardo organized the disciples into expressive groups of three, and his profound psychological insight into the human condition, continue to captivate audiences. This masterpiece, even in its fragile state, stands as a powerful testament to Leonardo’s genius and his relentless pursuit of artistic and emotional realism.” , “_words_section1”: “1994

Read more about: Leonardo da Vinci: Unpacking the Genius, His Masterpieces, and the Fascinating Secrets of a Renaissance Icon

7. **The Second Florentine Period: The Mona Lisa and Engineering Ambitions (1500-1508)**Following the French overthrow of Ludovico Sforza in 1500, Leonardo fled Milan, accompanied by his faithful assistant Salaì and the mathematician Luca Pacioli, seeking refuge in Venice. Here, his polymathic genius once again found a practical application, as he was engaged as a military architect and engineer, tasked with devising innovative methods to protect the city from potential naval assaults. His return to Florence in 1500 saw him welcomed as a guest of the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata, where he was provided with a workshop. It was during this period, as Vasari recounts, that Leonardo created a cartoon of *The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist*, a work that drew immense public admiration, with men and women, young and old, flocking to see it as if it were a solemn festival.

His restless spirit and diverse talents soon led him to new horizons. In 1502, Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the formidable son of Pope Alexander VI, taking on the role of chief military architect and engineer. This appointment saw him travel extensively across Italy with his patron, immersing himself in practical engineering challenges. He meticulously created a map of Cesare Borgia’s stronghold, a detailed town plan of Imola, to secure his patronage. Impressed by this precision, Borgia swiftly hired him. Later, Leonardo produced another strategic map, this time of the Chiana Valley in Tuscany, aimed at providing Borgia with a superior understanding of the terrain and an advantageous strategic position. His engineering ambitions extended even further, as he embarked on a project to construct a dam from the sea to Florence, envisioning a continuous water supply for the city’s canal system.

By early 1503, Leonardo had left Borgia’s service and returned to Florence, where he formally rejoined the Guild of Saint Luke on October 18. It was in this very month that he began working on what would become arguably the most famous painting in the world: a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the enigmatic subject of the *Mona Lisa*. This monumental undertaking would occupy him, in various capacities, for the remainder of his twilight years, a testament to his perfectionism and his deep engagement with the work. His standing in the Florentine artistic community was such that in January 1504, he was part of the esteemed committee tasked with recommending the ideal placement for Michelangelo’s iconic statue of David, a rare instance of direct collaboration among the era’s titans.

The ensuing two years saw Leonardo deeply engrossed in designing and painting a colossal mural, *The Battle of Anghiari*, for the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio. This ambitious commission was intended to be a companion piece to Michelangelo’s *The Battle of Cascina*, creating a visual dialogue between two of the greatest artistic minds of the age. However, like many of Leonardo’s experimental works, his painting tragically deteriorated rapidly, and is now known primarily through copies, most notably one by Rubens. In 1506, he was summoned back to Milan by Charles II d’Amboise, the acting French governor, where he took on Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Lombard aristocrat, who would become his most cherished student. The Council of Florence, eager for him to finish *The Battle of Anghiari*, eventually granted him leave at the behest of Louis XII, who considered commissioning portraits from the master. It is also believed that Leonardo may have commenced a project for an equestrian figure of d’Amboise during this period, with a wax model attributed to him surviving today, representing the only extant example of his sculptural work, though its attribution remains a subject of ongoing debate.

Read more about: Unveiling Leonardo da Vinci: A Renaissance Titan’s Enduring Legacy Across Art, Science, and Engineering

8. **Return to Milan and Roman Interlude: Later Scientific Pursuits (1508-1516)**By 1508, Leonardo had made his way back to Milan, establishing a residence in Porta Orientale within the parish of Santa Babila. This second Milanese period saw him continue his artistic and scientific explorations, often intertwining the two in his insatiable quest for knowledge. He embarked on plans for another ambitious equestrian monument, this time dedicated to Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. However, the political instability of the era once again thwarted his grand sculptural ambitions. An invasion by a confederation of Swiss, Spanish, and Venetian forces swiftly drove the French from Milan in 1512, disrupting his work and preventing the monument’s realization. Leonardo chose to remain in the city, spending several months in 1513 at the Medici’s Vaprio d’Adda villa, a testament to his resilience and deep connection to the region despite the shifting political landscape.

In September 1513, Leonardo journeyed to Rome, having been received by Giuliano de’ Medici, the brother of the newly elected Pope Leo X. For the next three years, until 1516, he resided primarily in the Belvedere Courtyard of the Apostolic Palace, a vibrant hub of artistic activity where even Michelangelo and Raphael were actively working. During this Roman sojourn, Leonardo was provided with a generous allowance of 33 ducats a month, signifying the high regard in which he was held, even if his unconventional approach sometimes perplexed his patrons. Vasari famously recounts an anecdote from this period, describing Leonardo’s whimsical decoration of a lizard with scales dipped in quicksilver, a charming glimpse into his playful and experimental nature. The Pope even granted him a painting commission of an unknown subject, but Leonardo, true to his innovative spirit, became preoccupied with developing a new type of varnish, leading to the commission’s eventual cancellation.

This Roman period was not without its personal challenges. Leonardo became ill, experiencing what may have been the first of a series of strokes that would ultimately precede his death. Despite these health setbacks, his intellectual curiosity remained undimmed. He diligently practiced botany within the serene confines of the Vatican Gardens, meticulously studying and documenting plant life, adding to his vast compendium of natural observations. Furthermore, he was commissioned to devise plans for the Pope’s ambitious project to drain the Pontine Marshes, demonstrating a continued engagement with large-scale civil engineering, an area where his theoretical understanding far outstripped the practical capabilities of his time.

His anatomical studies, a lifelong passion, also continued during this period. He dedicated himself to dissecting cadavers, making detailed notes and drawings for a treatise specifically focused on vocal cords. In a poignant attempt to regain the Pope’s favor, he presented these findings to an official, hoping the sheer intellectual weight of his discoveries would sway the pontiff. Unfortunately, this effort proved unsuccessful, highlighting the often-strained relationship between Leonardo’s boundless scientific inquiry and the more immediate demands of his patrons, even as he found himself in the midst of a city teeming with other artistic luminaries.

9. **Final Years in France: Patronage of Francis I and Legacy’s Dawn (1516-1519)**The political landscape of Italy continued its tumultuous shifts, and in October 1515, King Francis I of France recaptured Milan. This event, however, would prove to be a pivotal moment for Leonardo, leading to his final, serene chapter. On March 21, 1516, a letter from the royal advisor Guillaume Gouffier reached the French ambassador to the Holy See, Antonio Maria Pallavicini, conveying the French king’s explicit instructions to facilitate Leonardo’s relocation to France. The letter underscored the King’s eagerness for his arrival and sought to reassure Leonardo of a warm reception at court, both from the King himself and his mother, Louise of Savoy. Leonardo subsequently entered Francis’s service later that year, settling into the picturesque manor house of Clos Lucé, conveniently located near the royal Château d’Amboise.

This final period was marked by an exceptionally close and appreciative relationship with the young monarch, Francis I. The King frequently visited Leonardo at Clos Lucé, not merely as a patron but as an admiring friend and intellectual companion. Leonardo, in turn, continued to apply his multifaceted genius to various projects, drawing up elaborate plans for an immense castle town that the King envisioned erecting at Romorantin. Perhaps one of the most celebrated and whimsical creations from this period was a mechanical lion. During a grand pageant, this ingenious automaton reportedly walked towards the King and, upon being struck by a wand, dramatically opened its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies, a charming display of engineering artistry and courtly spectacle that encapsulated Leonardo’s blend of mechanics and theatre.

Throughout these final years, Leonardo was not alone; he was accompanied by his devoted friend and apprentice, Francesco Melzi, who remained a constant presence and support. It was during this time that Melzi captured a tender portrait of the aging master, one of the few known from his lifetime. Other contemporary sketches, including one by an unknown assistant from around 1517 and a drawing by Giovanni Ambrogio Figino depicting an elderly Leonardo with his right arm wrapped, corroborate an account of his right hand being paralytic when he was 65. This physical challenge provides a poignant insight into why some of his later works, such as the *Mona Lisa*, may have remained technically unfinished, despite his profound engagement with them. He persevered, continuing to work in some capacity until eventually succumbing to illness and becoming bedridden for several months.

Leonardo da Vinci passed away at Clos Lucé on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, possibly due to a stroke. The depth of his connection with Francis I is underscored by Vasari’s account, perhaps apocryphal but emotionally resonant, that the King held Leonardo’s head in his arms as he died. Vasari also describes Leonardo, on his deathbed, lamenting with repentance that he “had offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as he should have done,” and sending for a priest for confession and the Holy Sacrament, painting a picture of a man wrestling with his spiritual obligations even in his final moments. In accordance with his will, sixty beggars bearing tapers followed his casket, a humble yet fitting tribute. Melzi, his principal heir and executor, inherited his paintings, tools, library, and personal effects, ensuring the preservation of his invaluable legacy. His other long-time companion, Salaì, and his servant Baptista de Vilanis, each received half of his vineyards, while his brothers received land, and his serving woman a fur-lined cloak, marking the quiet passing of a colossus.

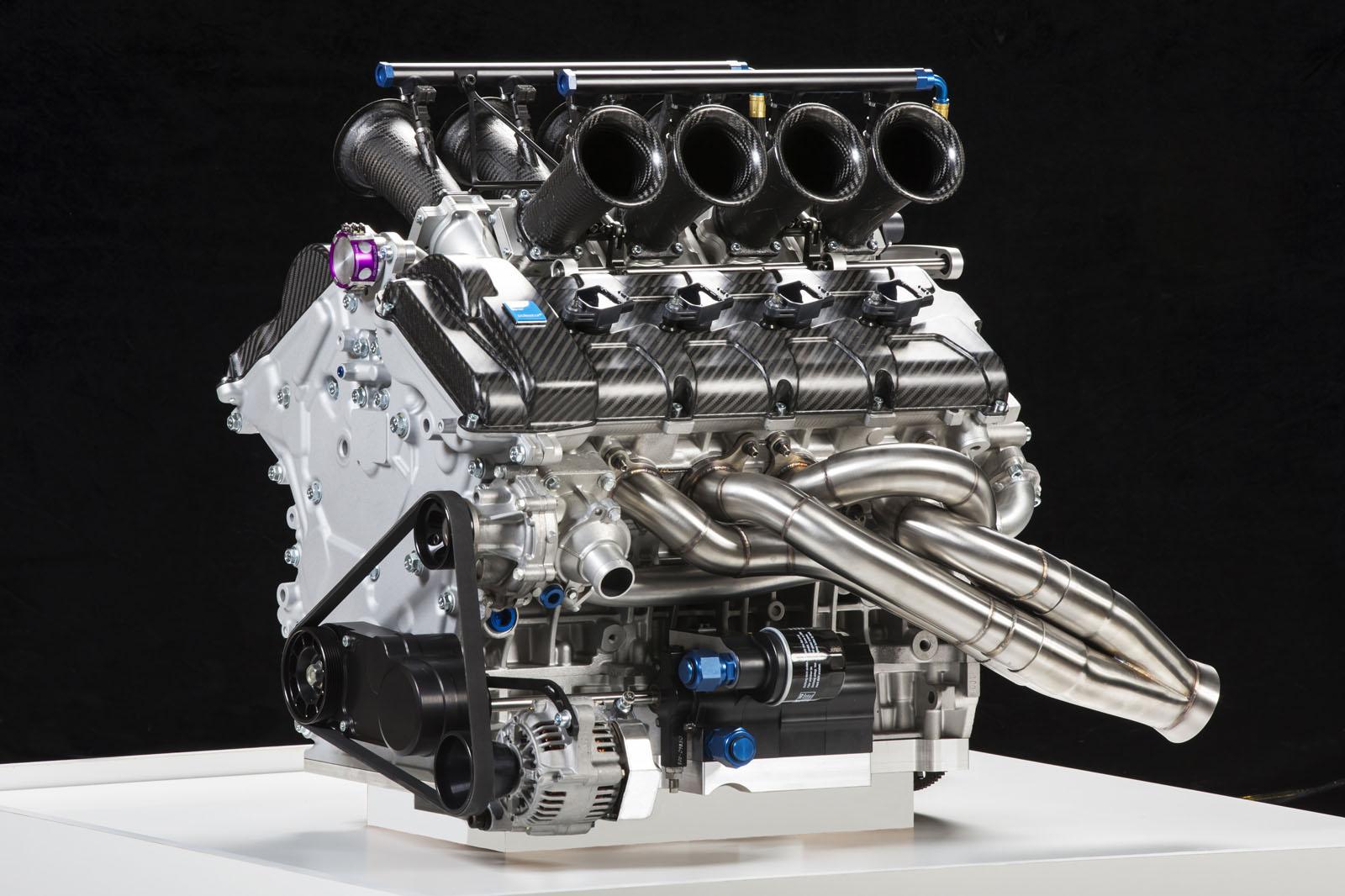

10. **The Unseen Architect: Engineering and Scientific Discoveries**While Leonardo’s fame as a painter has dominated the popular imagination for centuries, his true measure as a polymath cannot be fully grasped without delving into his breathtaking technological ingenuity. His notebooks are a testament to a mind that ceaselessly conceptualized advancements far beyond the capabilities of his era. He envisioned and meticulously sketched designs for flying machines, a rudimentary type of armored fighting vehicle, ingenious applications of concentrated solar power, a ratio machine that could be integrated into an adding machine, and even the innovative concept of the double hull for ships. These ideas, revolutionary in their scope, highlight a mind that was constantly pushing the boundaries of what was considered possible, often by centuries.

Yet, it is a poignant irony that relatively few of these groundbreaking designs were ever constructed, or even truly feasible, during his lifetime. The primary impediment was the rudimentary state of scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering during the Renaissance. The materials science, manufacturing techniques, and power sources required to bring many of his complex inventions to life simply did not exist. This meant that many of his most ambitious ideas remained confined to the pages of his notebooks, tantalizing glimpses of a future he could imagine but not fully manifest, a silent testament to a genius born too early for his own technological visions.

Despite the grand, often unbuilt, visions, some of Leonardo’s smaller, more practical inventions quietly made their way into the world of manufacturing, often unheralded. These more modest, yet equally ingenious, devices demonstrated his practical problem-solving skills and his keen eye for efficiency. Among these were an automated bobbin winder, a deceptively simple innovation that would have significantly improved textile production, and a machine designed for testing the tensile strength of wire, a critical tool for quality control in a burgeoning industrial landscape. These examples reveal that his inventive spirit was not solely focused on monumental concepts, but also on incremental, impactful improvements to everyday life and industry.

Beyond mechanical inventions, Leonardo made substantial, albeit largely unpublicized, discoveries across a vast spectrum of scientific disciplines. His relentless empirical inquiry led to profound insights in anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology (the study of friction, wear, and lubrication). However, a crucial aspect of his legacy in science is that he did not publish his findings. This meant that his groundbreaking observations and theoretical advancements had little to no direct influence on subsequent scientific development. The knowledge he painstakingly accumulated remained largely locked within his private notebooks, only to be fully appreciated and understood centuries after his death, underscoring both the depth of his scientific genius and the historical circumstances that limited its immediate impact on the wider scientific community.

11. **The Enigma of the Man: Personal Life and Relationships**Despite the thousands of pages Leonardo filled with drawings, notes, and observations in his voluminous notebooks and manuscripts, he remarkably left scarcely any direct reference to his personal life. This reticence only deepened the enigma of the man behind the masterpieces, making him a subject of endless fascination. Within his own lifetime, however, his extraordinary powers of invention, coupled with his “great physical beauty” and “infinite grace,” as effusively described by Vasari, certainly attracted considerable curiosity. One endearing facet of his personality, noted by Vasari, was his profound love for animals, which likely extended to vegetarianism and a well-known habit of purchasing caged birds merely to release them, a tender gesture that speaks volumes about his compassionate nature.

Leonardo cultivated many significant friendships with individuals who would become notable in their own right or for their historical importance. Among these was the esteemed mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on the influential book *Divina proportione* in the 1490s, blending art and mathematical theory. He also appears to have maintained close friendships with prominent women, notably Cecilia Gallerani, the likely subject of *Lady with an Ermine*, and the two Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella. While on a journey through Mantua, he drew a portrait of Isabella, which is believed to have served as the basis for a painted portrait that is now unfortunately lost, suggesting a circle of intellectual and artistic camaraderie that transcended conventional boundaries.

Beyond these friendships, Leonardo guarded his private life with intense secrecy, leading to centuries of conjecture about his uality. This speculation, beginning in the mid-16th century, was famously revived and explored in the 19th and 20th centuries, most notably by Sigmund Freud in his psychoanalytic study, *Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood*. It is widely believed that Leonardo’s most intimate and enduring relationships were with his pupils, particularly Salaì and Francesco Melzi. Melzi, in his poignant letter informing Leonardo’s brothers of his death, described the master’s feelings for his pupils as both “loving and passionate,” hinting at a profound emotional bond that transcended the typical master-apprentice dynamic.

Indeed, claims regarding the ual or erotic nature of these relationships have persisted since the 16th century. Modern biographers, such as Walter Isaacson, have explicitly stated their opinion that Leonardo’s relations with Salaì were intimate and homosexual. Historical records from 1476 show that at the age of twenty-four, Leonardo and three other young men faced charges of sodomy in an incident involving a known male prostitute. While these charges were ultimately dismissed due to a lack of evidence, and speculation exists that the Medici family exerted influence given that one of the accused, Lionardo de Tornabuoni, was related to Lorenzo de’ Medici, the incident has fueled much discussion about his presumed homosexuality and its perceived role in shaping his art. Scholars often point to the nuanced androgyny and subtle eroticism manifest in works like *Saint John the Baptist* and *Bacchus*, and more explicitly in certain erotic drawings, as reflections of this aspect of his personal life, offering a deeper understanding of the complex human experience he captured on canvas and paper.

Read more about: What Happened to Bridget Fonda? Unveiling the Enigmatic Retreat of a Hollywood Royal, From Silver Screen Stardom to a Deliberately Private Life

12. **A Pantheon of Masterpieces: Iconic Works and Enduring Influence**For the better part of four hundred years following his death, Leonardo da Vinci’s towering fame rested almost exclusively on his achievements as a painter. Despite having numerous lost works and a relatively small corpus of fewer than 25 attributed major works—many of which remain unfinished—he nonetheless created some of the most influential and enduring paintings in the entire Western canon. By the 1490s, his extraordinary talent had already earned him the epithet of a “Divine” painter, a testament to the profound impact his artistry had on his contemporaries and successive generations.

Among these extraordinary creations, the small portrait known universally as the *Mona Lisa*, or *La Gioconda*, stands as arguably the most famous painting in the world in our present era. Its enduring allure rests, in particular, on the elusive, enigmatic smile gracing the woman’s face, a mysterious quality that is perhaps due to the subtly shadowed corners of her mouth and eyes. This masterful technique, which prevents the exact nature of her expression from being definitively determined, came to be known as *sfumato*, or “Leonardo’s smoke,” a signature style that imbues his subjects with an unprecedented sense of life and psychological depth. Vasari himself, in his famed biographical accounts, wrote that the smile was “so pleasing that it seems more divine than human, and it was considered a wondrous thing that it was as lively as the smile of the living original.” The painting’s unadorned dress focuses attention on the eyes and hands, while the dramatic, almost fantastical landscape background, suggesting a world in flux, and the impossibly smooth, blended brushwork all contribute to its unparalleled mystique and technical brilliance.

Beyond the *Mona Lisa*, Leonardo’s artistic legacy is punctuated by other universally recognized icons. His *Vitruvian Man* drawing, a harmonious blend of art and science depicting human proportions, is revered globally as a cultural icon, symbolizing the Renaissance humanist ideal and the intricate connection between humanity and the cosmos. In a more contemporary testament to his enduring value, his *Salvator Mundi*, attributed in whole or part to him, achieved a staggering record in 2017 when it sold at auction for US$450.3 million, becoming the most expensive painting ever sold at public auction, a stark reminder of the immense commercial and cultural cachet that his name still commands.

The profound qualities that render Leonardo’s work utterly unique are multifaceted and have been endlessly discussed by connoisseurs and critics alike. These include his innovative techniques for laying on paint, his extraordinarily detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany, and geology—all meticulously applied to his canvases—and his keen interest in physiognomy, the subtle ways humans register emotion through expression and gesture. Furthermore, his innovative use of the human form within figurative compositions, and his pioneering application of subtle gradation of tone, contributed to an unprecedented realism and emotional resonance in his art. These qualities converge brilliantly in his most celebrated painted works, including not only the *Mona Lisa*, but also *The Last Supper* and *The Virgin of the Rocks*, each a masterclass in composition, psychological insight, and technical innovation.

Read more about: Stuart Craig: The Visionary Production Designer Who Architected the Magical Worlds of Harry Potter, Dies at 83

From the humble Tuscan hills of Vinci to the opulent courts of Florence, Milan, Rome, and France, Leonardo da Vinci’s journey was one of relentless curiosity and unparalleled genius. His achievements, diverse interests, personal life, and empirical thinking have, since his death in 1519, never failed to incite interest and admiration, cementing his status as a frequent namesake and subject in culture. He was a man who not only painted masterpieces but also conceptualized worlds yet to be discovered, a universal genius whose spirit of inquiry and artistic brilliance continues to illuminate and inspire, forever linking the realms of art and science in a tapestry woven by his singular vision.