According to the Old Testament of the Bible, Aaron (pronounced AIR-ən or ARR-ən) was an Israelite prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of Moses. Information about Aaron comes exclusively from religious texts, including the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament (Luke, Acts, and Hebrews), and the Quran. His multifaceted roles and complex character make him a figure of profound significance in Abrahamic faiths.

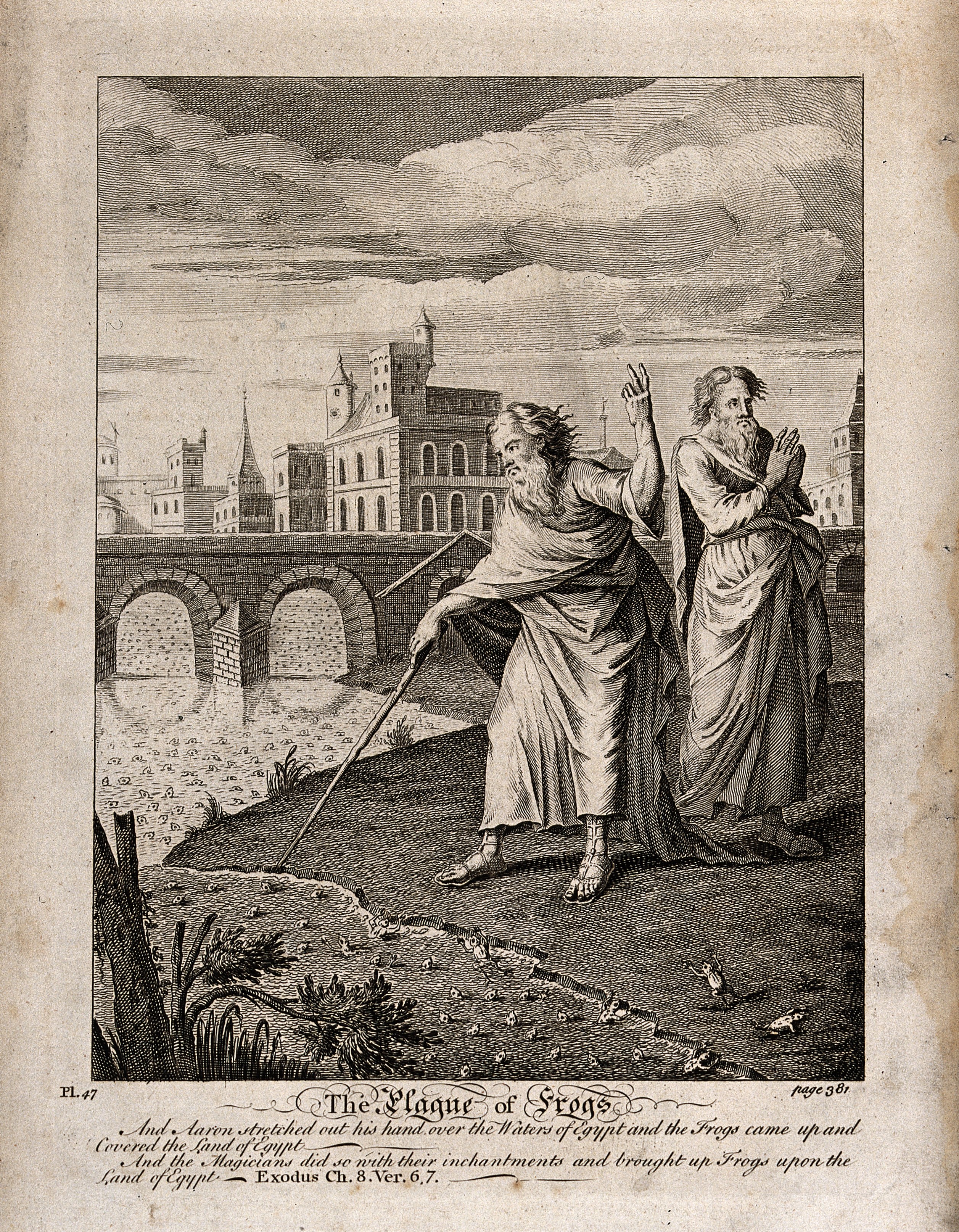

Unlike Moses, who grew up in the Egyptian royal court, Aaron and his elder sister Miriam remained with their kinsmen in the northeastern Nile Delta. Aaron’s pivotal public role began when Moses first confronted the Egyptian king about the enslavement of the Israelites, with Aaron serving as his brother’s spokesman to the Pharaoh. The Book of Exodus narrates that God appointed Aaron as Moses’ “prophet” due to Moses’ complaint that he could not speak well. At Moses’ command, he let his rod turn into a snake. He then stretched out his rod to bring on the first three plagues. After that, Moses tended to act and speak for himself.

A cornerstone of Aaron’s enduring legacy is his anointment as the first High Priest of the Israelites. The Law given to Moses at Sinai granted Aaron and his male descendants the priesthood exclusively. This established a lineage, making Levitical priests, or kohanim, traditionally believed and halakhically required to be of direct patrilineal descent from Aaron. The books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers assert Aaron received from God a monopoly over the priesthood for himself and his male descendants. His family had the exclusive right and responsibility to make offerings on the altar to Yahweh, while other Levites were assigned subordinate duties within the sanctuary.

Moses anointed and consecrated Aaron and his sons to the priesthood, arraying them in the robes of office. God’s detailed instructions for performing their duties were related to them, with the Israelites listening. Aaron and his successors were given control over the Urim and Thummim, by which God’s will could be determined. The Aaronide priests were commissioned to distinguish the holy from the common and the clean from the unclean, and to teach the divine laws (the Torah) to the Israelites. They were also commissioned to bless the people.

The divine approbation of the newly instituted Aaronide priesthood was powerfully manifested during its inauguration. When Aaron completed the altar offerings for the first time, he and Moses “blessed the people, and the glory of the LORD appeared unto all the people.” Then, “there came a fire out from before the LORD, and consumed upon the altar the burnt offering and the fat [which] when all the people saw, they shouted and fell on their faces.” In this way, the institution of the Aaronide priesthood was established.

Aaron’s journey through the wilderness was marked by conflict. During Moses’ prolonged absence on Mount Sinai, the people provoked Aaron to make a golden calf, an act that nearly caused God to destroy the Israelites. Moses successfully intervened, leading loyal Levites in executing many culprits; a plague afflicted those remaining. Aaron, however, escaped punishment for his role due to Moses’ intercession, according to Deuteronomy 9:20. Later retellings, including rabbinic sources and the Quran, often excuse Aaron, portraying him as not the idol-maker and acting under mortal threat from the Israelites.

On the day of Aaron’s consecration, his oldest sons, Nadab and Abihu, were burned by divine fire for offering “strange” incense. Most interpreters view this as reflecting a conflict between priestly families or showing the consequences of disobeying God’s instructions. While the Torah depicts Moses, Aaron, and Miriam as Israel’s leaders, Numbers 12 reports that Aaron and Miriam complained about Moses’ exclusive claim to be the LORD’s prophet. God rebuffed their presumption, affirming Moses’ uniqueness, and punished Miriam with a skin disease. Aaron pleaded for Miriam, and she was healed after seven days, with Aaron once again escaping retribution.

According to Numbers 16–17, a Levite named Korah led many in challenging Aaron’s exclusive claim to the priesthood. When the rebels were punished by being swallowed up by the earth, Eleazar, Aaron’s son, was commissioned to take charge of the dead priests’ censers. When a plague broke out among the people sympathizing with the rebels, Aaron, at Moses’ command, took his censer and stood between the living and the dead until the plague abated, thereby atoning.

To emphasize the validity of the Levites’ claim to offerings and tithes, Moses collected a rod from the leaders of each tribe, laying the twelve rods overnight in the tent of meeting. The next morning, Aaron’s rod was found to have budded, blossomed, and produced ripe almonds. The rod was then placed before the Ark of the Covenant to symbolize Aaron’s right to priesthood. The following chapter details the distinction: while all Levites were devoted to the sanctuary’s care, charge of its interior and the altar was committed to the Aaronites alone.

Aaron, like Moses, was not permitted to enter Canaan with the Israelites. This stemmed from Moses striking a rock twice for water instead of speaking to it, which showed a lack of deference to the LORD. The Torah provides two accounts of Aaron’s death. Numbers says that after the Meribah incident, Aaron, his son Eleazar, and Moses ascended Mount Hor, where Moses stripped Aaron of his priestly garments, transferring them to Eleazar. Aaron died on the summit, and the people mourned him for thirty days.

Deuteronomy 10:6, however, places these events at Moseroth, where Aaron died and was buried. There is a significant amount of travel between these two points, as Numbers 33:31–37 records seven stages between Moseroth (Mosera) and Mount Hor. Aaron died on the 1st of Av and was 123 at the time of his death.

Aaron married Elisheba, daughter of Amminadab and sister of Nahshon of the tribe of Judah. His sons were Nadab, Abihu, Eleazar, and Ithamar, though only the latter two had progeny. A descendant of Aaron is an Aaronite, or Kohen, meaning Priest. Any non-Aaronic Levite assisted the Levitical priests of Aaron’s family in the care of the tabernacle, later the temple. The Gospel of Luke records that both Zechariah and Elizabeth, and their son John the Baptist, were descendants of Aaron.

Thomas Römer argues that external evidence and biblical texts suggest the Pentateuch reflects unresolved tensions among three groups: a lay group aligned with Moses, a priestly group linked to Aaron, and the Levites. These tensions, evident during the Persian and early Hellenistic periods, are seen in conflicting narratives concerning Moses and Aaron. Compromises are evident in texts like Exodus and Leviticus, where they work together, though Moses is dominant. Disagreements persisted, with some texts emphasizing Moses’s superiority and others elevating Aaron’s status. The Pentateuch preserves these unresolved conflicts while portraying Moses as the unparalleled mediator of the Torah (Deut. 34:10–12).

The older prophets and prophetical writers viewed priests as representing an inferior religious form, lacking spirit and will to resist idolatry. Thus Aaron, the first priest, ranked below Moses, serving as his mouthpiece and executor of God’s will revealed through Moses, despite the Torah stating “the Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron” fifteen times. Under the priesthood’s influence during Persian rule, a different priestly ideal formed, tending to place Aaron equal with Moses, per Malachi 2:4–7. The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael implies this equality, stating, “At times Aaron, and at other times Moses, is mentioned first in Scripture—this is to show that they were of equal rank,” introducing a glowing description of Aaron’s ministration.

In fulfillment of the promise of peaceful life, symbolized by the pouring of oil upon his head, Aaron’s death, as described in the aggadah, was of a wonderful tranquility. Accompanied by Moses and Eleazar to Mount Hor, Aaron entered a beautiful cave where Moses instructed him to transfer his priestly garments to Eleazar before lying down. His soul departed “as if by a kiss from God,” and angels were seen carrying his bier through the air after the cave closed behind Moses. A voice then proclaimed his righteousness, “The law of truth was in his mouth, and iniquity was not found on his lips, he walked with me in righteousness and brought many back from sin.”

He died on the first of Av, and the pillar of cloud guiding Israel’s camp disappeared at his death. The seeming contradiction between Numbers 20:22 et seq. and Deuteronomy 10:6 is resolved by rabbis. They explain Aaron’s death on Mount Hor was followed by a war defeat, causing a retreat to Mosera for mourning rites, hence the saying, “There [at Mosera] died Aaron.”

The rabbis particularly praise the brotherly sentiment between Aaron and Moses. When Moses was appointed ruler and Aaron high priest, neither betrayed jealousy; instead, they rejoiced in each other’s greatness. When Moses first declined to go to Pharaoh, unwilling to deprive Aaron of his high position, the Lord reassured him: “Behold, when he sees you, he will be glad in his heart.” Shimon bar Yochai noted Aaron’s heart, which “had leaped with joy over his younger brother’s rise to glory greater than his,” was decorated with the Urim and Thummim, to “be upon Aaron’s heart when he goeth in before the Lord.”

Moses and Aaron met in “gladness of heart,” kissing as true brothers, leading to the saying: “Behold how good and how pleasant [it is] for brethren to dwell together in unity!” Of them it is said: “Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed [each other]”; for Moses stood for righteousness and Aaron for peace, with mercy personified in Aaron and truth in Moses.

When Moses poured the oil of anointment upon Aaron’s head, Aaron modestly shrank back, fearing he might have cast some blemish upon the sacred oil. However, the Shekhinah spoke, “Behold the precious ointment upon the head that ran down upon the beard of Aaron, that even went down to the skirts of his garment is as pure as the dew of Hermon.” According to Tanhuma, Aaron’s activity as a prophet began earlier than that of Moses.

Hillel held Aaron up as an example, saying, “Be of the disciples of Aaron, loving peace and pursuing peace; love your fellow creatures and draw them nigh unto the Law!” Tradition asserts Aaron was an ideal priest, far more beloved for his kindly ways than was Moses. While Moses was stern and uncompromising, Aaron was a peacemaker, reconciling man and wife or neighbor with neighbor, winning evildoers back by friendly intercourse.

As a result, Aaron’s death was more intensely mourned than Moses’: when Aaron died, the “whole house of Israel wept,” including the women, while Moses was bewailed by “the sons of Israel” only. Even in the making of the golden calf, the rabbis find extenuating circumstances for Aaron. His fortitude and silent submission to God’s will on the loss of his two sons are referred to as an excellent example. Particularly significant are God’s words: “Say to thy brother Aaron: Greater than the gifts of the princes is thy gift; for thou art called upon to kindle the light, and, while the sacrifices shall last only as long as the Temple lasts, thy light shall last forever.”

In the Eastern Orthodox and Maronite churches, Aaron is venerated as a saint whose feast day is shared with his brother Moses and celebrated on September 4. Churches following the traditional Julian calendar observe this on September 17. Aaron is also commemorated with other Old Testament saints on the Sunday of the Holy Fathers, the Sunday before Christmas.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, he is commemorated on July 20, March 12, Sunday of the Forefathers, Sunday of the Fathers, and on April 14 with all the saint Sinai monks. The Armenian Apostolic Church commemorates him on July 30. He is also commemorated on July 1 in the modern Latin and Syriac calendars. The Moses and Aaron Church in Amsterdam is a well-known Catholic church. One Bible version describes Aaron’s role as the “spokesman for Moses.”

In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Aaronic priesthood is the lesser order of priesthood under the higher Melchizedek priesthood. Those ordained have authority to act in God’s name in certain responsibilities, such as sacrament administration and baptism. In the Community of Christ, the Aaronic order is an appendage to the Melchisedec order, consisting of deacon, teacher, and priest. While differing in responsibilities, these offices are regarded as equal before God.

Aaron (Arabic: Hārūn) is mentioned in the Quran as a prophet of God. The Quran praises Aaron repeatedly, calling him a “believing servant” as well as one who was “guided” and one of the “victors.” The Quran additionally denies Aaron’s role in the creation of the golden calf, attributing the action to Samiri. Aaron is important in Islam for his role in the Exodus, in which he preached with his younger brother, Musa (Moses), to the Pharaoh. Islamic tradition accords Aaron the role of a patriarch, as priestly descent came through Aaron’s lineage, including the entire House of Amran.

In the Baháʼí Faith, Aaron is described as a prophet. While his father, Imran, is described as both an apostle and a prophet, Aaron is merely described as a prophet. The Kitáb-i-Íqán describes Imran as his father.

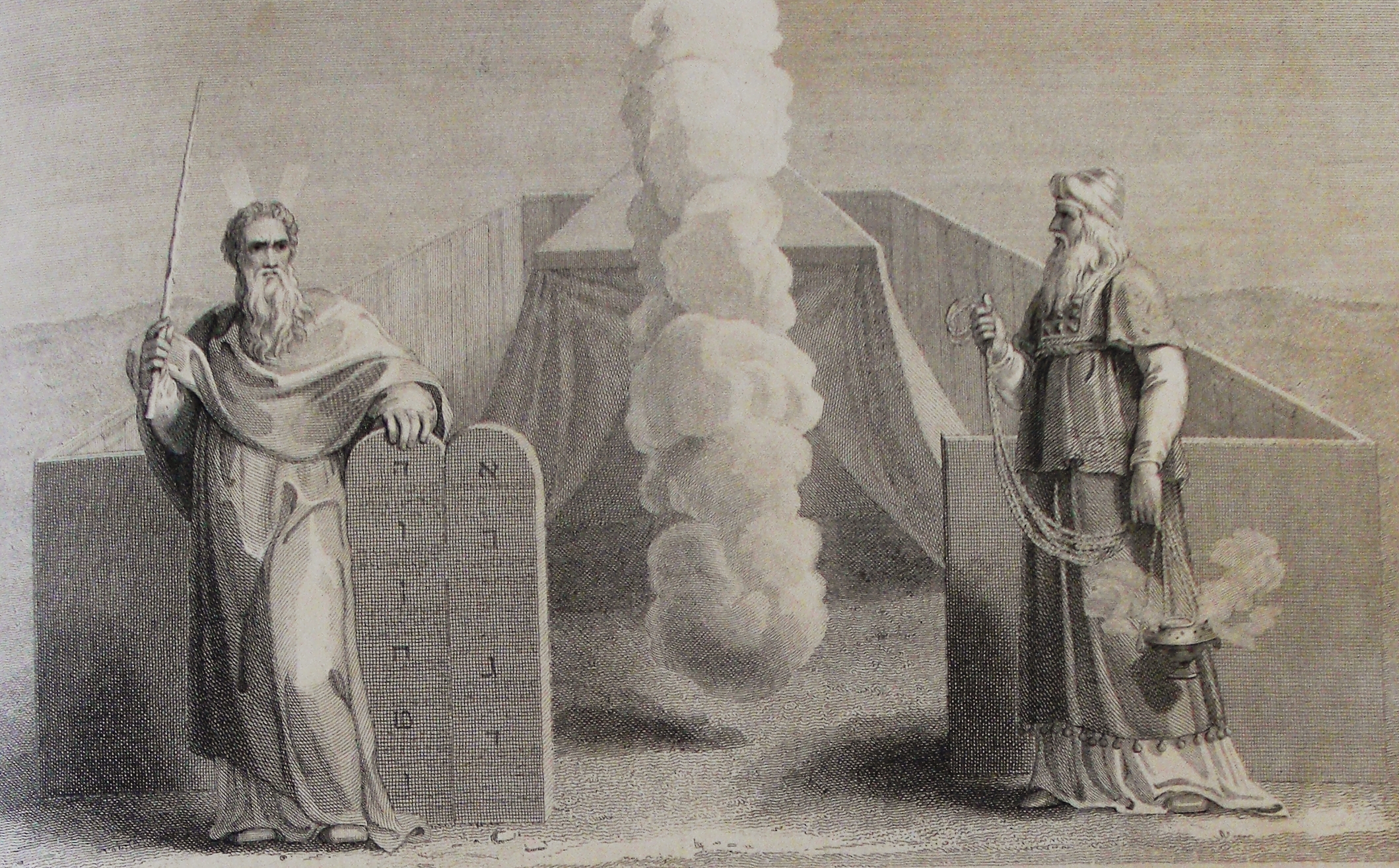

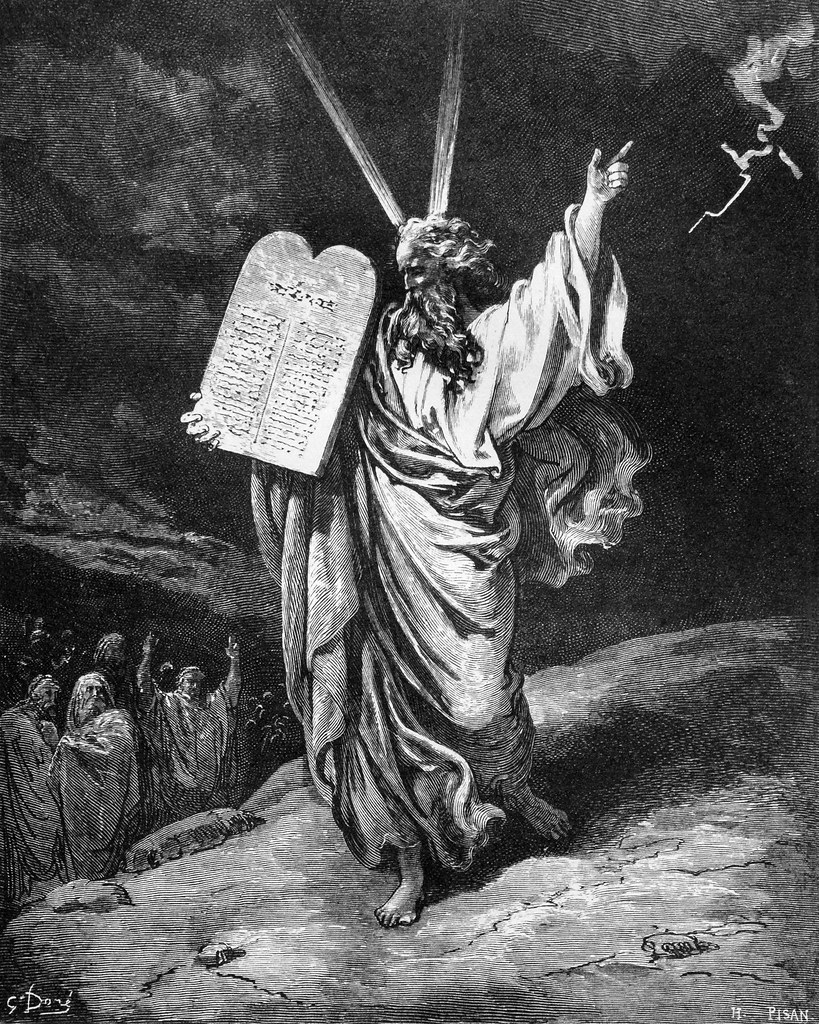

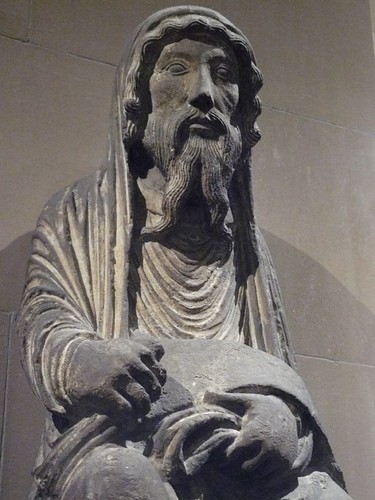

Aaron appears paired with Moses frequently in Jewish and Christian art, especially in illustrations of manuscript and printed Bibles. He can usually be distinguished by his priestly vestments, particularly his turban or miter and jeweled breastplate. He frequently holds a censer or his flowering rod. Aaron also appears in scenes depicting the wilderness Tabernacle and its altar, as seen in third-century frescos in the synagogue at Dura-Europos. An eleventh-century portable silver altar from Fulda depicts Aaron with his censor, located in the Musée de Cluny.

This is also how he appears in the frontispieces of early printed Passover Haggadot and occasionally in church sculptures. Aaron has rarely been the subject of portraits, such as those by Anton Kern and by Pier Francesco Mola. Christian artists sometimes portray Aaron as a prophet holding a scroll, as in a twelfth-century sculpture from the Cathedral of Noyon in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and often in Eastern Orthodox icons. Illustrations of the Golden Calf story usually include him as well – most notably in Nicolas Poussin’s The Adoration of the Golden Calf.

Finally, some artists interested in validating later priesthoods have painted the ordination of Aaron and his sons (Leviticus 8). Harry Anderson’s realistic portrayal is often reproduced in the literature of the Latter-day Saints. Aaron has been depicted in Exodus-related drama, such as The Ten Commandments (1956) and Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014).

Aaron’s narrative, woven through the fabric of Abrahamic faiths, transcends that of a mere assistant; it reveals a complex and indispensable figure whose life profoundly shaped religious institutions and beliefs. From his initial role as Moses’ spokesman to his foundational establishment as Israel’s first high priest, Aaron’s contributions were monumental. Despite moments of human fallibility, his ultimate forgiveness and continued divine favor underscored his unique standing. His lineage established the enduring priesthood, a cornerstone for generations of religious practice. His story remains a vibrant testament to leadership, devotion, and the intricate dynamics of faith, continuing to inspire and inform believers across millennia, underscoring his universal resonance across faiths.