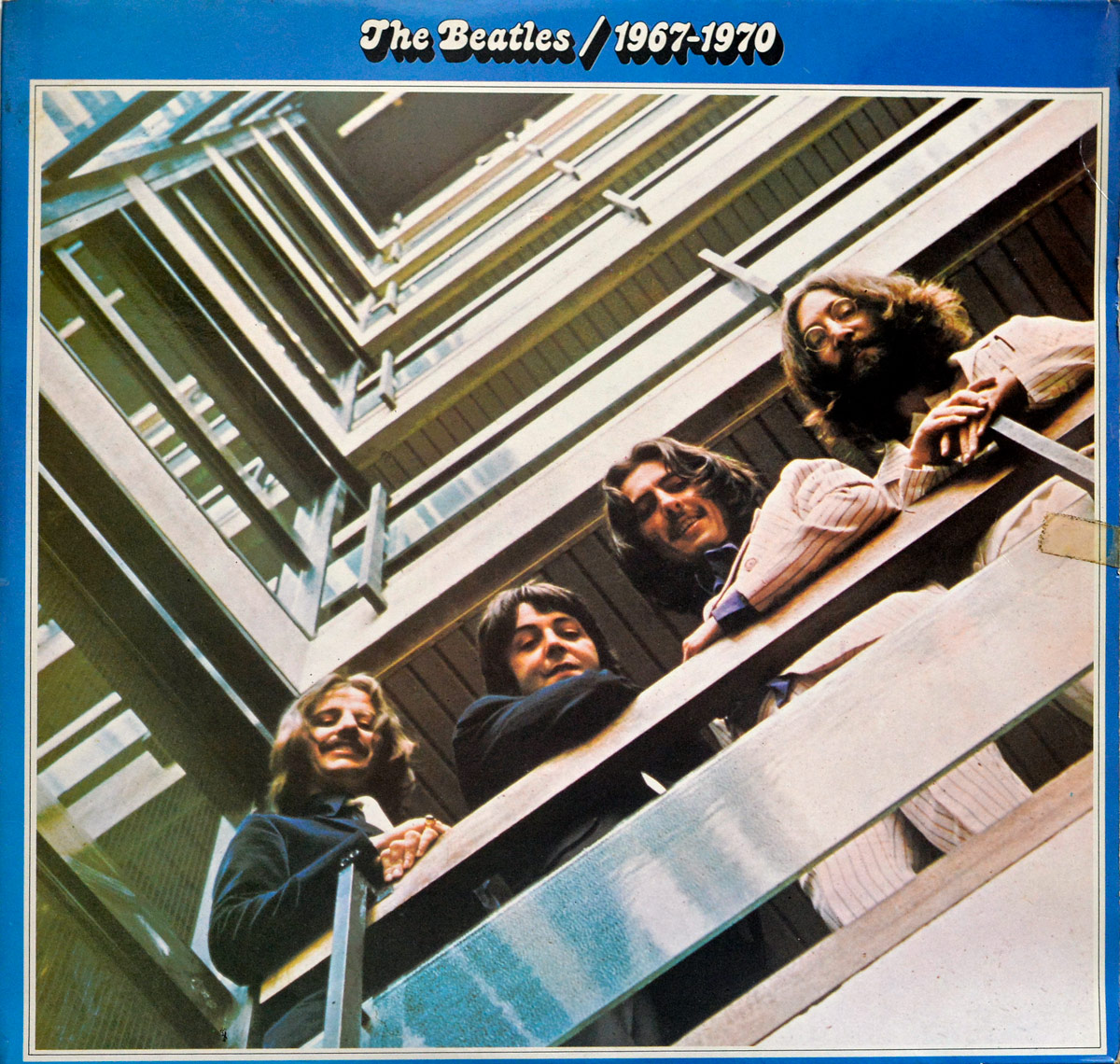

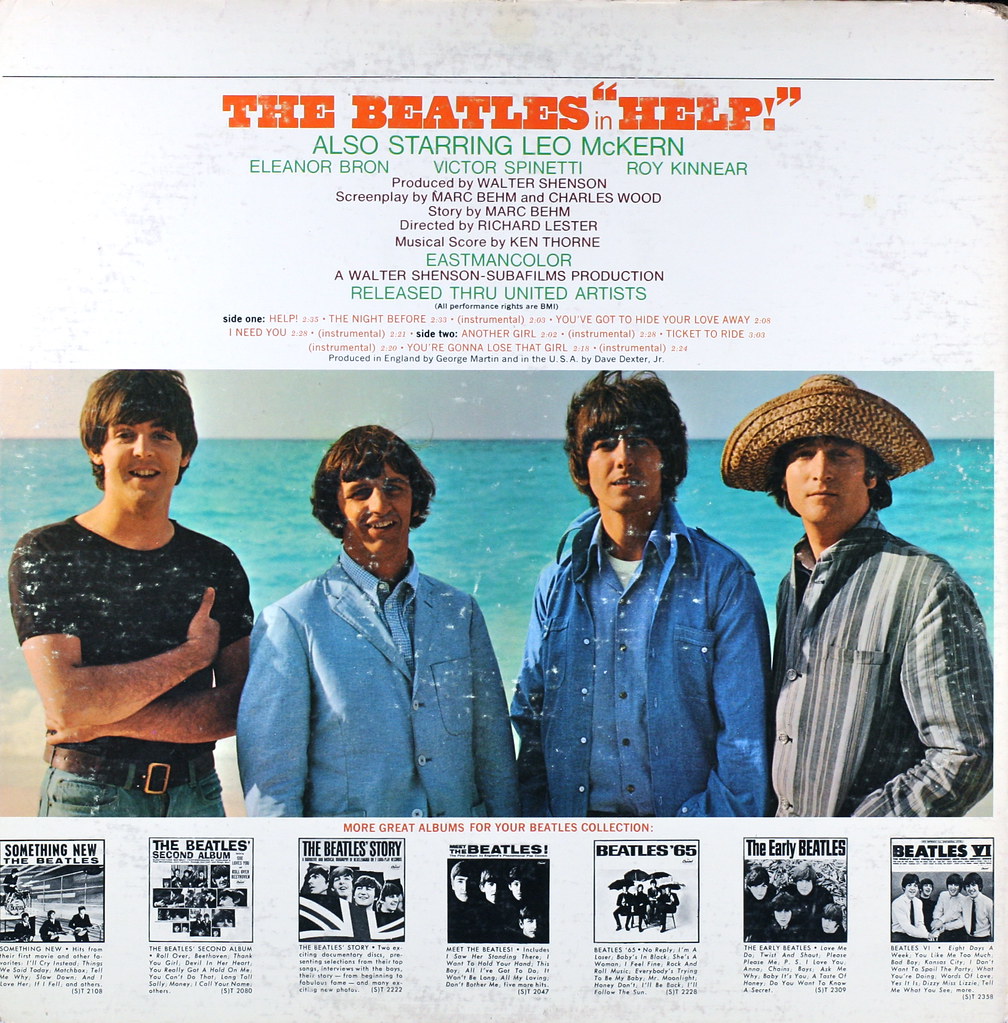

The Beatles. Their name alone conjures images of a cultural phenomenon that reshaped the world. Yet, their epic journey, like all others, had an end. While *Let It Be* was released later, *Abbey Road*, meticulously crafted in summer 1969, marked the Fab Four’s final collective studio recordings. This monumental work, with its iconic zebra crossing cover, has long been shrouded in myths. Beneath the surface, however, lies a compelling narrative: The Beatles’ definitive, albeit often subconscious, final message to the world and to themselves.

*Abbey Road* stands as a testament to both their enduring genius and the profound fissures within the band. It was born from Paul McCartney’s desire to “make an album the way we used to do it,” alongside the undeniable reality of an impending split. This tension, this blend of nostalgic collaboration and fracturing ambition, imbued the record with bittersweet resonance. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the sprawling, audacious Side Two Medley – a sonic trapdoor revealing the band’s “underground world,” a culmination of Beatlemania and personal strife. This sixteen-minute, eight-track symphony, their farewell magnum opus, encapsulates seven years as a band. We delve deep into its layers, offering a definitive guide to the meaning woven into *Abbey Road*’s remarkable tapestry and its powerful, poignant goodbye.

1. **The Medley’s Genesis: A Farewell Magnum Opus** The *Abbey Road* Side Two Medley’s inception profoundly shapes The Beatles’ final message. By 1969, internal dynamics were strained, with individual aspirations diverging. Yet, Paul McCartney, alongside producer George Martin, conceived an idea to transform disparate song fragments into a cohesive, symphonic statement. Martin noted, “Paul was all for experimenting like that.”

The medley wasn’t merely a pragmatic solution for unfinished ideas. It was an artistic decision deeply impacting the album’s narrative. Paul’s “brainwave” was to knit together snippets from *The White Album* sessions and others into a flowing composition. This structure allowed seamless transitions between lyrical and musical themes, mirroring The Beatles’ tumultuous path.

It was a conscious effort to evoke thematic grandeur, akin to *Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band*. But this time, the journey was explicitly towards an end. It became The Beatles’ final symphony, a sixteen-minute, eight-track farewell magnum opus, representing their seven years as a band.

This deliberate artistic culmination, born from ingenuity and the need to coalesce fragmented ideas, underscores the band’s desire to conclude their collective output with a statement of lasting significance. It was a final, ambitious flourish before their inevitable parting.

2. **The Medley’s Core Message: The Toll of Fame and Self-Indulgence** Beyond its structural innovation, the *Abbey Road* medley carries a poignant, multifaceted message. It serves as an almost autobiographical reflection on the reasons for the band’s end. The overarching theme is a stark commentary on the corrosive effects of manic fame.

The Beatles, having experienced unparalleled global adoration, became acutely aware of how lavish lifestyles and constant pressures fostered selfishness and an obsession with money. This often eclipsed their musical creativity. This interpretation suggests the medley is a candid examination of their own downfall.

This self-awareness is powerfully articulated through the lyrical motifs woven throughout. The lyrics touch upon material desires, the sense of being trapped by success, and a longing for simpler existence. It’s a confessional exploration of the psychological and emotional toll Beatlemania exacted.

Ultimately, the medley explains why their extraordinary journey had to conclude. It’s a narrative of disillusionment, where idealism gave way to the realities of a demanding, isolating profession. By confronting these themes, The Beatles sent a message about the hidden costs of unparalleled global stardom.

3. **”You Never Give Me the Money”: Opening the Medley’s Narrative** The *Abbey Road* medley commences with “You Never Give Me the Money,” setting a somber, cynical tone. It directly addresses materialism and exploitation, indicative of the band’s internal strife, particularly surrounding financial disputes. This opening track embodies the resentment that festered, a significant catalyst for their eventual break-up.

The lyrics are a clear expression of disillusionment, touching upon unpaid dues, broken promises, and being caught in a trap. It speaks to a world where artistic integrity was increasingly compromised by commercial pressures. This candidness about financial anxieties underlines the mature, often jaded perspective The Beatles had developed.

Unlike their earlier carefree exuberance, the song signals a more world-weary outlook permeating the medley. By placing this track at the beginning, The Beatles immediately anchor their final message in harsh realities. It introduces underlying grievances, a sense of being consumed by a system they once mastered.

The song is not just a lament about money. It’s a metaphor for betrayal and eroding trust, crucial to understanding “the reasons why the band had to come to an end.” It lays bare the destructive forces of business conflicts.

4. **”Carry That Weight” and “Mean Mr Mustard”: Echoes of Burden and Obsession** As the *Abbey Road* medley progresses, “Carry That Weight” and “Mean Mr Mustard” deepen the narrative of the band’s struggles. They echo the burdens of fame and personal obsessions. “Mean Mr Mustard,” an Esher demo, introduces a character study of a miserly individual.

This figure critiques, perhaps even self-critiques, the materialism and self-absorption the band observed as a side effect of success. It continues the financial motif from “You Never Give Me the Money.” “Carry That Weight” then serves as one of the most direct and emotionally resonant statements within the medley.

The repeated refrain, “Boy, you’re gonna carry that weight, carry that weight a long time,” acknowledges the lasting impact of their journey. It speaks to collective and individual responsibility, lingering pressures, and indelible experiences that would forever define their lives after The Beatles.

These songs articulate a sense of being burdened, not only by external fame and its constant demands, but also by internal conflicts. “Mean Mr Mustard” paints a picture of wealth’s isolating effects, while “Carry That Weight” expresses the profound, inescapable legacy each Beatle would bear.

5. **”She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” and “Golden Slumbers”: Intrusions and Simple Pleasures**

The medley’s narrative takes an intimate turn with “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” and “Golden Slumbers.” These tracks illustrate the extreme invasiveness of fame and the longing for normalcy. “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” is a direct, autobiographical account of a fan intruding on Paul McCartney’s home.

This incident perfectly encapsulates the erosion of privacy The Beatles endured. Personal spaces became public domains, highlighting the constant siege mentality fame fostered. It reveals the complete loss of boundaries between artist and admirer.

Conversely, “Golden Slumbers,” with its tender melody, represents a yearning for innocence and tranquility lost amidst superstardom’s chaos. Its lullaby-like quality evokes a desire for “simpler pleasures,” a stark contrast to the intrusion described just moments before. It’s a heartfelt plea for peace and respite.

These songs, placed in close proximity, powerfully comment on celebrity’s dual nature. They articulate a profound yearning for a return to a pre-fame existence, where one could sleep in “golden slumbers” without intrusion. They reveal the human cost behind the myth, showcasing a craving for basic comforts.

6. **”The End”: The Final Sentiments on Love and Legacy** The *Abbey Road* medley, and indeed the album, culminates with “The End.” It provides closure and delivers a profound philosophical statement: “In the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.” This iconic line summarizes their journey, acknowledging the cyclical nature of relationships and effort.

It offers reflective wisdom gained from years of extraordinary experience, transcending specific internal conflicts to speak a universal truth. Musically, “The End” is a showcase of individual virtuosity, featuring Ringo Starr’s only drum solo on a Beatles record. This is followed by guitar solos from Paul, George, and John.

This instrumental segment, a rare moment where each member is spotlighted, can be seen as a final, unified musical conversation. It’s a poignant display of their unique talents, emphasizing that despite differences, their individual voices created something extraordinary together.

The lyrical resolution dictates the message: while they may have made “irreconcilable mistakes along the way” and “fame is a self-indulgent circle,” the experience was one of immense love. This closing sentiment suggests final acceptance of their fate and a nuanced understanding of their legacy.

Read more about: Reclaiming the Road: Why Stick Shift Cars Are Roaring Back into Style for Modern Drivers and Enthusiasts

7. **”Her Majesty”: The Accidental Hidden Track** In a delightful and uniquely Beatlesque twist, “The End” is subtly undermined by the accidental inclusion of “Her Majesty” as a hidden track. This brief, twenty-three-second acoustic snippet, originally intended as a bridge within the medley, found its way to the album’s conclusion through a studio “accident.”

Tape operator John Kurlander, instructed “never to throw anything away,” retrieved the excised snippet and appended it to the end of the master tape. This serendipitous placement created one of the world’s first “hidden tracks.” Paul McCartney was initially “keen on dropping Her Majesty” entirely.

However, the unexpected addition proved a charming surprise. Accounts suggest even the Fab Four eventually “loved how it ended up there by accident.” This element of chance and the band’s embrace of it speaks volumes about their evolving, often playful, approach to art.

The presence of “Her Majesty” as an unlisted, accidental finale significantly alters the album’s concluding message. Instead of a purely philosophical farewell, it adds quirky, almost self-deprecating humor, a final wink. This accidental ending, initially a production error, ultimately became an iconic, beloved feature of *Abbey Road*.

The profound narrative woven into *Abbey Road* extends beyond its lyrical farewells, reaching into the very fabric of its creation. While the Side Two Medley offered a powerful, introspective goodbye, the recording sessions themselves were a microcosm of The Beatles’ complex, evolving dynamic. It was a period marked by both moments of genuine collaboration and undeniable friction, set against a backdrop of groundbreaking technical innovation that would forever shape the album’s distinctive sound. To truly understand the final message, one must delve into the atmosphere of these sessions, the pivotal figures who guided them, and the crucial decisions that underscored the band’s impending dissolution.

8. **The Collaborative Yet Fractured Recording Atmosphere** By 1969, The Beatles’ internal landscape was undeniably fraught. Paul McCartney aimed to “make an album the way we used to do it,” yet George Martin recalled in the *Anthology* documentary that “Nobody knew for sure that it was going to be the last album,” but “everybody felt it was.” This unspoken premonition permeated the studio, creating bittersweet tension where flashes of old camaraderie intertwined with stark reminders of their diverging paths.

These sessions, despite a “more collegial atmosphere” than *Get Back*, were not harmonious. Yoko Ono’s “permanent presence” and “acrimonious argument with Lennon” from McCartney highlighted deep personal and artistic rifts. These were foundational cracks in a relationship that had defined a generation.

John Lennon’s desire for “all of his songs on one side… and McCartney’s on the other” revealed the band’s individualism. While the album compromised, Lennon later dismissed the medley as “junk” and McCartney’s contributions as “[music] for the grannies to dig.” George Harrison’s reflection that “it felt as if we were reaching the end of the line” encapsulates the pervading sense of finality.

9. **George Martin: The ‘Fifth Beatle’s’ Guiding Hand** George Martin’s role was more crucial than ever in navigating the *Abbey Road* sessions. McCartney initially proposed to “make an album the way we used to do it,” and Martin agreed, but only “on the strict condition that all the group—particularly John Lennon—allow him to produce the record in the same manner as earlier albums and that discipline would be adhered to.” This firm stance addressed the challenges of uniting increasingly individualistic members.

Martin’s creative input proved indispensable, especially for the ambitious Side Two Medley. He had “a significant role to play” in realizing Paul’s “brainwave” to knit disparate song fragments into a cohesive, symphonic statement. His vision transformed unfinished ideas into a “farewell magnum opus,” elevating individual contributions into a grand artistic statement.

His perspective on the band’s split offers poignant insight. In *Anthology*, Martin noted, “The Beatles had gone through so much… I was surprised that they had lasted as long as they did.” His observation that “I wasn’t at all surprised that they’d split up because they all wanted to lead their own lives” highlights the immense pressure. Despite difficulties, Martin’s dedication never wavered, culminating in “Come Together,” which “stands out because of the sheer brilliance of the performers.”

10. **Revolutionary Sound: The Dawn of Eight-Track and Solid-State Engineering** *Abbey Road* marked a significant sonic leap due to crucial technical innovations. For the first time, The Beatles recorded on “eight-track reel-to-reel tape machines rather than the four-track machines” used previously. This doubling of tracks offered unprecedented flexibility for overdubbing and layering, creating the rich, dense soundscapes characteristic of the album.

Pioneeringly, *Abbey Road* was “the first Beatles album not to be issued in mono anywhere in the world.” Furthermore, the entire album was recorded through the new “solid-state transistor mixing desk, the TG12345 Mk I,” replacing older tube desks. This new console superiorly supported eight-track recording and facilitated extensive overdubbing, contributing to a distinct sound.

The TG12345 desk significantly impacted *Abbey Road*’s sound. Engineer Geoff Emerick noted it had “individual limiters and compressors on each audio channel” and produced a “softer” sound. Kenneth Womack summarized its effect: “the expansive sound palette… enabled George Martin and Geoff Emerick to imbue the Beatles’ sound with greater definition and clarity… providing listeners with an abiding sense that the Beatles’ final long-player was markedly different.” Assistant engineers Alan Parsons and John Kurlander also contributed their talents to this sonic masterpiece.

11. **The Moog Synthesiser: Harrison’s Sonic Signature** Among the striking technical innovations was the prominent incorporation of the Moog synthesiser, largely introduced by George Harrison. Having acquired one in November 1968, Harrison had already used it on his *Electronic Sound* album. His fascination brought a fresh, otherworldly dimension to The Beatles’ final recordings, showcasing their continuous exploration of new sonic frontiers.

The Moog wasn’t just a background effect; it often played a “central role.” In “Because,” its distinctive, swirling tones are masterfully employed for the middle eight, adding a haunting, ethereal quality. Its presence is also notable on “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” contributing to its quirky atmosphere, and on “Here Comes the Sun,” infusing it with unique warmth.

Harrison’s embrace of the Moog underscored his growing artistic independence and technical prowess. His innovative use became a subtle yet significant signature on *Abbey Road*, distinguishing it from previous works. It was a testament to his individual sonic exploration, enriching the album’s tapestry with a futuristic edge.

12. **Crafting the A-Sides: “Come Together” and “Something”** The two standout singles, “Come Together” and “Something,” represent pivotal track decisions, shaping the album’s success and revealing evolving individual artistry. “Come Together,” an expansion of a John Lennon song for Timothy Leary, became a rock anthem. Its opening line, “Here come old flat-top,” led to a copyright lawsuit with Morris Levy, highlighting the complexities of their post-Beatles careers.

Despite legal issues, “Come Together” was lauded for its execution. George Martin described it as “a simple song but it stands out because of the sheer brilliance of the performers,” attesting to their collective musicianship. Lennon’s “sardonic self-portrait” blended wit and introspection, making it a powerful statement track.

Harrison’s “Something” became The Beatles’ first non-Lennon–McCartney number-one single, and the first single from an already released UK album. Inspired by James Taylor, its tender melody and lyrical depth earned praise from Lennon and McCartney. Frank Sinatra’s declaration that it was “the greatest love song ever written” cemented its timeless appeal, showcasing Harrison’s burgeoning genius.

13. **”Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “Oh! Darling”: The Album’s Points of Contention** *Abbey Road* is cohesive, yet “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and “Oh! Darling” reveal its underlying tension. McCartney’s “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” previously rejected for *The White Album* as “too complicated,” became a “fraught” recording. McCartney’s insistence on “a perfect performance” exasperated bandmates.

John Lennon “hated it and declined to do so,” dismissing it as “more of Paul’s granny music,” showcasing artistic divergence. George Harrison called it “a real drag,” while Ringo Starr pragmatically admitted it was “granny music, but we needed stuff like that.” This track, featuring Mal Evans on anvil and McCartney on Moog, thus reflects both McCartney’s vision and the band’s simmering frustrations.

“Oh! Darling,” another McCartney composition, added to the production narrative. Written in a doo-wop style, McCartney “attempted recording the lead vocal… for several days” to capture its raw emotion. Though less contentious, his relentless pursuit of artistic perfection, while defining his genius, also exacerbated strains within the group. These songs illustrate the challenging atmosphere of *Abbey Road*’s creation.

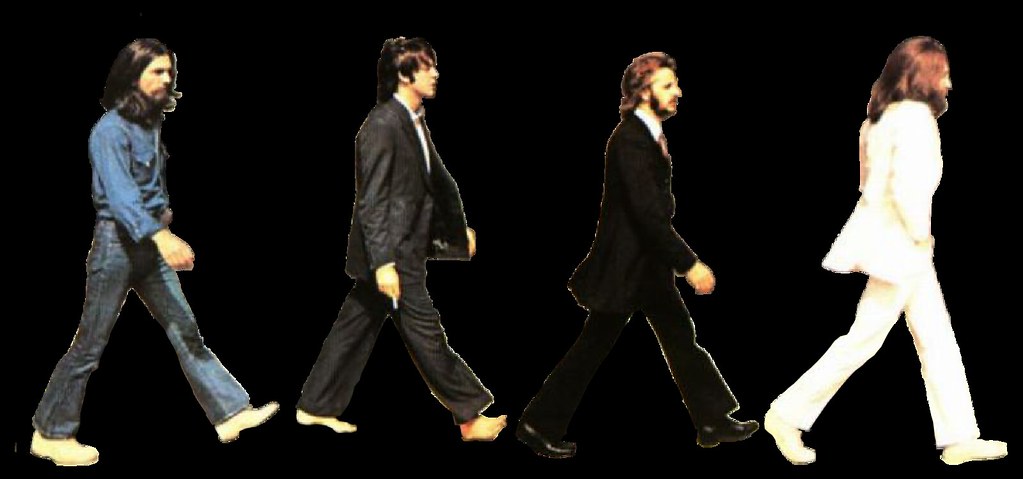

14. **The Final Sequencing: A Last Collective Act (and Lennon’s Departure)** The Beatles’ final collective studio act occurred on August 20, 1969, their “final day at Abbey Road Studios.” No music was recorded; instead, they spent “seven hours discussing song sequencing.” This crucial moment shaped the track order, unaware it was their last joint creative act. The album they left was “unrecognizable” from its final form.

Significant changes were made. Initially, “the sides were reversed, with the LP’s famous medley closing out the first side and ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’ ending Abbey Road.” “Octopus’s Garden” and “Oh! Darling” were also in “opposite places.” These adjustments, made remotely over the following week, underscored their commitment to a cohesive artistic statement amidst personal fractures. Lennon’s instruction to “cut the tape to create an abrupt ending” for “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” exemplified his vision for impactful conclusions.

While these sequencing decisions showed strained collaboration, dissolution loomed. “Nobody knew for sure that it was going to be the last album,” but “everybody felt it was,” George Martin recalled. It was “the beginning of the end.” A month later, “Lennon announced his exit from the band,” marking the official end. *Abbey Road*, with its iconic medley and accidental hidden track, became The Beatles’ last collective artistic testament, a powerful, complex farewell.

In reflecting upon the making of *Abbey Road*, its genius lies not only in its unparalleled music but also in its complex narrative of human endeavor. The blend of individual aspirations, personal frictions, and a collective commitment to artistic excellence, all amplified by cutting-edge studio technology, created an album that transcended the sum of its parts. It stands as a powerful testament to The Beatles’ enduring legacy, a final, intricate message delivered with both profound musicality and deeply human vulnerability, forever cementing their place in the pantheon of cultural icons.