The United States of America, often simply known as the U.S. or America, stands as a sprawling federal republic, a nation whose very fabric has been woven through centuries of profound transformations and formidable challenges. Primarily situated in North America, this country extends across a vast continental expanse, encompassing 50 states, a federal capital district in Washington, D.C., and several island territories. With its 48 contiguous states bordering Canada and Mexico, alongside the semi-exclave of Alaska and the Pacific archipelago of Hawaii, the U.S. is truly a megadiverse country, boasting the world’s third-largest land area and an expansive population exceeding 340 million. This immense geographic and demographic scale has long underpinned its significant role in global political, cultural, economic, and military affairs.

To truly grasp the essence of America today, one must delve into the intricate layers of its past, recognizing how each era has contributed to its unique character. From the ancient migrations that populated the continent to the seismic shifts of revolution, civil conflict, and economic upheaval, the nation has consistently navigated periods that tested its foundational principles and reshaped its trajectory. This comprehensive journey through its history reveals how periods of immense growth and prosperity have often been juxtaposed with internal strife, deeply rooted societal divisions, and profound shifts in its identity and global standing.

This in-depth examination will unfold across a series of pivotal moments, charting the course of a nation frequently pushed to its limits yet consistently re-emerging in new forms. We will journey through the pre-Columbian eras, the crucible of European colonization, the birth of a revolutionary republic, and the deep divisions that led to civil war and profound social restructuring. Each segment aims to illuminate the forces that have driven America’s ongoing evolution, fostering a deeper understanding of its complex identity and its enduring, often challenging, place in the world.

1. **Indigenous Peoples and Early North America**: The story of North America begins not with European arrival, but with the rich and varied tapestry of Indigenous cultures that thrived across the continent for millennia. Over 12,000 years ago, Paleo-Indians embarked on a remarkable migration from North Asia, crossing into North America and establishing the earliest human presence. These original inhabitants, forming diverse civilizations, laid the foundational patterns of life across the vast landscape.

Among the earliest discernible widespread cultures was the Clovis culture, appearing around 11,000 BC, demonstrating sophisticated hunting techniques and tool-making. As time progressed, Indigenous North American cultures evolved, exhibiting increasing complexity and ingenuity. The Mississippian cultures, for instance, developed advanced agriculture, impressive mound architecture, and intricate social hierarchies in the midwestern, eastern, and southern regions. Similarly, the Algonquian peoples flourished in the Great Lakes area and along the Eastern Seaboard, while the Hohokam culture and Ancestral Puebloans established distinct and enduring societies in the arid southwest.

The sheer scale of pre-Columbian habitation in what is now the United States is striking, with native population estimates ranging from approximately 500,000 to nearly 10 million before the influx of European immigrants. These vibrant societies, with their deep spiritual connections to the land, their unique forms of governance, and their sustainable practices, represented a highly developed and multifaceted world that would profoundly encounter the dramatic changes brought by European contact.

2. **European Exploration, Colonization, and Conflict (1513–1765)**: The arrival of European powers profoundly reshaped the North American continent, initiating an era of exploration, ambitious colonization, and pervasive conflict. Spain led the way, with Christopher Columbus’s expeditions from 1492, swiftly establishing Spanish-speaking settlements and missions from present-day Puerto Rico and Florida across to New Mexico and California. Spanish Florida, chartered in 1513, was the first European colony in what is now the continental United States, with Saint Augustine founded in 1565 as Spain’s first permanent town in the region.

Other European nations rapidly followed. France established settlements along the Great Lakes (Fort Detroit, 1701), the Mississippi River (Saint Louis, 1764), and the Gulf of Mexico (New Orleans, 1718). The robust Dutch colony of New Nederland, settled in 1626, later became New York, while the small Swedish colony of New Sweden was established in 1638 in what is now Delaware, adding to the diverse European presence.

British colonization, foundational for the future United States, began decisively along the East Coast with the Virginia Colony in 1607 and the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1620. These and the other original Thirteen Colonies developed unique precedents for representative self-governance, notably through the Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut. Relations with Native Americans were a complex mix of trade and severe conflict, often involving policies compelling Indigenous peoples to adopt European lifestyles. Simultaneously, the transatlantic slave trade forcibly brought enslaved Africans to the eastern seaboard, providing labor for the Southern Colonies’ plantation economies and sowing deep societal divisions. The significant geographical distance from Britain fostered self-governance, and the First Great Awakening fueled colonial interest in guaranteed religious liberty, all setting the stage for future contention.

3. **The American Revolution and the Early Republic (1765–1800)**: The period from 1765 to 1800 represents a crucible in American history, as rising tensions between the British Crown and its American colonies ignited a revolutionary struggle. Britain’s assertion of greater control, particularly through taxation without direct parliamentary representation, became a primary grievance, galvanizing colonial political resistance. The First Continental Congress convened in 1774, implementing the Continental Association, a colonial boycott of British goods that signaled their discontent effectively.

Open warfare erupted with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, igniting the American Revolutionary War. The Second Continental Congress then appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief and tasked a committee, including Thomas Jefferson, to draft the Declaration of Independence. Adopted on July 4, 1776, this seminal document articulated the core political values: liberty, inalienable individual rights, and the sovereignty of the people, explicitly rejecting monarchy and hereditary political power.

The Founding Fathers, including Washington, Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin, drew deeply from Classical, Renaissance, and Enlightenment philosophies. American sovereignty was internationally recognized by the Treaty of Paris (1783) after the British surrender at Yorktown, granting the U.S. vast territory stretching west to the Mississippi River. The Northwest Ordinance (1787) established a crucial precedent for future state admissions. To address the limitations of the decentralized Articles of Confederation, the U.S. Constitution was drafted at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, going into effect in 1789. It created a federal republic with three separate branches and a system of checks and balances. George Washington’s election as the first president and the adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 solidified the framework for the new nation, setting precedents for peaceful power transfer.

4. **Westward Expansion and the Divisive Civil War (1800–1865)**: The early to mid-19th century in the United States was defined by an accelerating push westward, fueled by a powerful sense of “manifest destiny.” This era fundamentally reshaped the nation’s geographic footprint, beginning with the monumental Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France, which nearly doubled the existing territory and opened vast new lands. Further significant acquisitions followed, including Spain ceding Florida in 1819 and the 1846 Oregon Treaty, securing U.S. control over the present-day American Northwest. The annexation of the Republic of Texas in 1845 and the subsequent victory in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) led to the 1848 Mexican Cession, bringing new states like New Mexico and California under U.S. sovereignty and extending the nation decisively to the Pacific coast. However, this dramatic territorial growth was inextricably entwined with the deepening and increasingly volatile conflict over slavery. Historically entrenched as the main labor force in the Southern Colonies’ agriculture-dependent economies, slavery became a central point of contention, with its profitability solidified by inventions like the cotton gin (1793). The Missouri Compromise of 1820 attempted a delicate balance by admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, and by prohibiting slavery in future Louisiana Purchase lands north of a specific parallel, yet this was merely a temporary reprieve.

The period also saw aggressive and often tragic policies of Indian removal. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, a key initiative of President Andrew Jackson, forcibly displaced an estimated 60,000 Native Americans from east of the Mississippi River. This tragic event, known as the Trail of Tears (1830–1850), resulted in between 13,200 and 16,700 deaths during the forced march. Ongoing settler expansion and the influx of Indigenous peoples from the East fueled further American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi. Compounding these pressures, the California gold rush of 1848–1849 spurred a massive migration of white settlers to the Pacific coast, leading to increased confrontations and violence against Native populations, including what is described as the California genocide, which lasted into the mid-1870s and further underscored the human cost of rapid expansion.

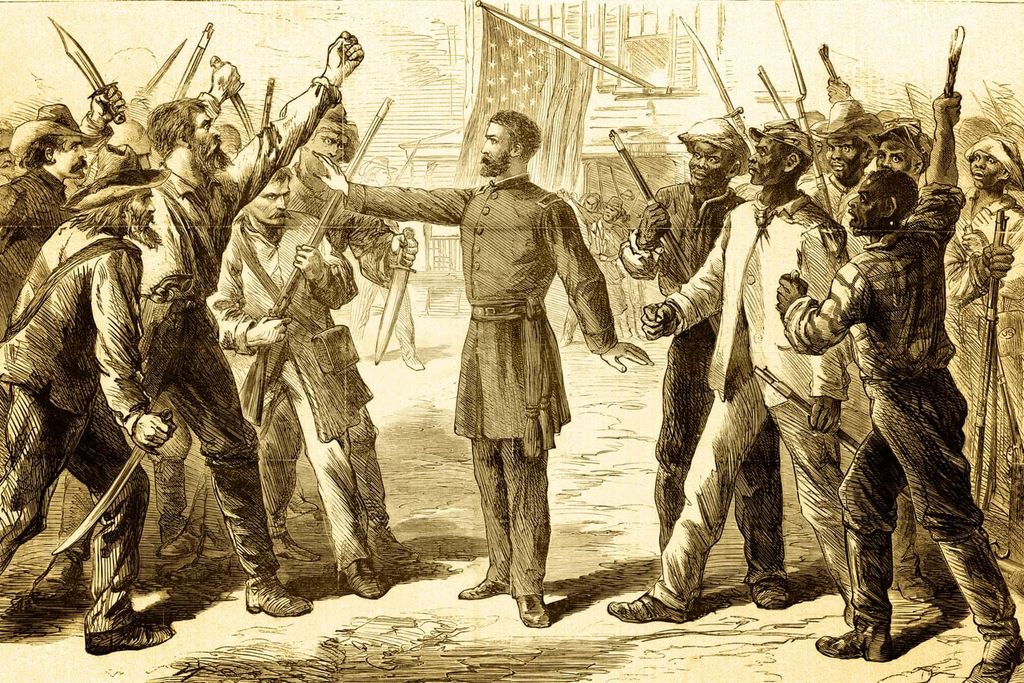

Sectional conflict over slavery intensified throughout the 1850s, inflamed by national legislation and Supreme Court decisions that heightened tensions between North and South. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 mandated the forcible return of escaped slaves to their owners, while the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 effectively nullified the anti-slavery provisions of the Missouri Compromise. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857 further exacerbated tensions by ruling against a slave seeking freedom and declaring the entire Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. These escalating issues ultimately culminated in the American Civil War (1861–1865), as eleven slave-state governments seceded from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America. War erupted in April 1861 with the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter. A pivotal shift occurred with the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which encouraged many freed slaves to join the Union army. Union victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg turned the tide, leading to the Confederate surrender in 1865 after the Union’s decisive victory at Appomattox Court House, marking reunification and the national abolition of slavery, irrevocably altering the nation’s social and political fabric.

America’s journey through the late 19th and 20th centuries into the present day is a testament to its enduring capacity for transformation, marked by profound impacts from industrialization, global conflicts, social movements, and rapid technological advancements. These eras have irrevocably shaped its contemporary identity and continue to present unique challenges and opportunities. As we transition from the crucible of the Civil War, the nation embarked on new chapters of integration, economic dynamism, and evolving social structures, often punctuated by periods of immense turmoil and significant reform.

This segment will meticulously examine the pivotal historical epochs that have defined the modern United States, tracing its path from post-Civil War reconstruction and the Gilded Age’s economic booms to its emergence on the world stage through global conflicts, the profound societal shifts of the Cold War, and the complex realities of the contemporary era. Each period reveals layers of American resilience, innovation, and ongoing struggle for its ideals, offering a deeper understanding of the forces that have forged the nation we recognize today.

5. **Reconstruction, Gilded Age, and Progressive Era (1863–1917)**: Following the Union’s victory in the American Civil War and the national abolition of slavery, efforts toward reconstruction in the secessionist South commenced as early as 1862. However, it was after President Lincoln’s assassination that three crucial Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution were ratified. These amendments solidified the national abolition of slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crimes, promised equal protection under the law for all persons, and prohibited discrimination based on race or previous enslavement, fundamentally reshaping the legal and social landscape of the reunited nation.

In the decade immediately following the Civil War, African Americans actively participated in the political life of the former Confederate states. Concurrently, the former Confederate states were gradually readmitted to the Union, a process that began with Tennessee in 1866 and concluded with Georgia in 1870, marking a significant step toward national reunification. Beyond the political sphere, the expansion of national infrastructure, notably the transcontinental telegraph and railroads, spurred immense growth across the American frontier, a movement further accelerated by the Homestead Acts, which provided nearly 10 percent of the total land area of the United States free to some 1.6 million homesteaders, fundamentally altering demographic patterns and land ownership across the vast interior.

Yet, this period of immense growth and change was not without its profound challenges and societal regressions. The Compromise of 1877, which resolved the electoral crisis following the 1876 presidential election, is widely regarded as the conclusion of the Reconstruction era, leading President Rutherford B. Hayes to reduce the federal military presence in the South. This shift immediately allowed “Redeemers” to regain local control of Southern politics in the name of white supremacy, initiating a period of heightened and overt racism for African Americans, often referred to as the nadir of American race relations. A series of Supreme Court decisions, including *Plessy v. Ferguson*, significantly weakened the force of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, permitting the unchecked implementation of Jim Crow laws in the South, the establishment of “sundown towns” in the Midwest, and widespread segregation across the country, further reinforced by the federal policy of redlining.

Economically, the late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed an explosion of technological advancement, coupled with the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor, leading to rapid economic expansion that allowed the United States to surpass the combined economies of England, France, and Germany. This era, often termed the Gilded Age, saw the amassing of unprecedented power by prominent industrialists, who often formed trusts and monopolies to stifle competition, particularly in the railroad, petroleum, and steel industries, and saw the United States emerge as a pioneer of the automotive industry. However, these changes also resulted in significant increases in economic inequality, the emergence of dire slum conditions, and growing social unrest, creating a fertile environment for labor unions and socialist movements to flourish as they sought to address the burgeoning social disparities. This dynamic period of unchecked industrial growth and social tension eventually transitioned into the Progressive Era, a period characterized by significant reforms aimed at addressing the societal ills that had become entrenched. Concurrently, the United States expanded its territorial holdings beyond the contiguous states, annexing the Hawaiian islands in 1898 after pro-American elements overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy, and acquiring Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam from Spain that same year following the Spanish-American War, with the Philippines later gaining full independence in 1946. American Samoa was acquired in 1900, and the U.S. Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1917, marking a period of increasing American influence on the global stage.

6. **World War I, Great Depression, and World War II (1917–1945)**: The early 20th century propelled the United States onto the global stage, marking a decisive shift from its previous isolationist tendencies. In 1917, the United States entered World War I alongside the Allies, a critical intervention that significantly contributed to turning the tide against the Central Powers, signaling America’s newfound military and economic clout. Domestically, this period also saw a momentous advance in civil rights: in 1920, a constitutional amendment was ratified, granting nationwide women’s suffrage, a culmination of decades of advocacy and a monumental step toward greater democratic inclusion.

The 1920s and 1930s were transformative years for American communication, with the widespread adoption of radio for mass communication and the nascent emergence of early television. These technologies profoundly reshaped the national dialogue, bringing information and entertainment directly into American homes. However, this era of burgeoning modernity was dramatically interrupted by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, an event that triggered the Great Depression, the most severe economic downturn in American history. President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded to this unprecedented crisis with the New Deal, a comprehensive plan based on principles of “reform, recovery, and relief.” This initiative comprised a series of sweeping recovery programs and employment relief projects, combined with extensive financial reforms and regulations, designed to stabilize the economy and alleviate widespread suffering, fundamentally altering the relationship between the government and its citizens.

Initially maintaining a position of neutrality as global conflicts escalated, the United States gradually became an indispensable arsenal for democracy. In March 1941, the U.S. began supplying crucial war materiel to the Allies of World War II. Its direct involvement became unavoidable in December of that year, following the Empire of Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, propelling the nation fully into the global conflict. The war effort galvanized American industry and society, leading to unprecedented mobilization. A pivotal and harrowing development during this period was the U.S.’s development of the first nuclear weapons, which were subsequently used against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, effectively bringing World War II to a conclusive end. In the aftermath of the war, the United States emerged relatively unscathed, its industrial capacity intact and its economy significantly strengthened. Alongside the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China, the U.S. became one of the “Four Policemen” who met to plan the post-war world order, securing its position as a global economic power with significantly increased international political influence.

7. **Cold War and Social Revolution (1945–1991)**: The conclusion of World War II in 1945 left the United States and the Soviet Union as the world’s preeminent superpowers, each commanding its own political, military, and economic sphere of influence. This bipolar global structure inevitably led to a period of intense geopolitical tensions and ideological competition, known as the Cold War. In response to the perceived Soviet threat, the United States adopted a policy of containment, aiming to limit the USSR’s global influence, and engaged in various covert and overt actions, including regime change against governments perceived to be aligned with Moscow. This geopolitical rivalry extended into technological and scientific competition, most notably in the Space Race, a contest in which the U.S. ultimately prevailed with the historic first crewed Moon landing in 1969, a monumental achievement that captivated the world.

Domestically, the United States experienced a period of robust economic growth, accelerated urbanization, and significant population expansion following World War II. However, this prosperity was juxtaposed with deep-seated social inequalities that spurred transformative movements. The Civil Rights Movement gained significant momentum, with Martin Luther King Jr. emerging as a prominent leader in the early 1960s, challenging racial segregation and discrimination through non-violent protest. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration launched the “Great Society” plan, which resulted in groundbreaking and broad-reaching laws, policies, and a constitutional amendment specifically designed to counteract some of the most pervasive effects of lingering institutional racism, striving to create a more equitable society. Concurrently, the counterculture movement brought significant social changes, including the liberalization of attitudes toward recreational drug use and sexuality. This period also saw widespread opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam, encouraging open defiance of the military draft, which ultimately led to the end of conscription in 1973, and the eventual total withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam in 1975.

Another profound societal shift during this era involved the changing roles of women. The 1970s witnessed a significant increase in female paid labor participation, largely attributable to evolving societal norms and increased opportunities. By 1985, the majority of American women aged 16 and older were employed, marking a fundamental redefinition of family structures and economic contributions. The final years of this period brought about a monumental shift in global geopolitics: the Fall of Communism and the dissolution of the Soviet Union from 1989 to 1991 signaled the definitive end of the Cold War. This left the United States as the world’s sole superpower, a status that significantly cemented its global influence and reinforced the concept of the “American Century,” signifying its unparalleled dominance in international political, cultural, economic, and military affairs.

8. **Contemporary (1991–Present)**: The dawn of the post-Cold War era in the 1990s ushered in a period of unprecedented domestic prosperity and rapid technological advancement for the United States. This decade saw the longest recorded economic expansion in American history, coupled with a dramatic decline in U.S. crime rates, fostering a sense of optimism and stability. Technological innovations flourished, many emerging or being significantly improved upon in the U.S., including the World Wide Web, the continuous evolution of the Pentium microprocessor in accordance with Moore’s law, the development of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, the first gene therapy trial, and breakthroughs in cloning. Pioneering scientific endeavors such as the Human Genome Project were formally launched in 1990, and the Nasdaq became the first stock market in the United States to trade online in 1998, indicative of a new digital age.

While largely focused on domestic growth, the United States continued to play a decisive role in global affairs. In the Gulf War of 1991, an American-led international coalition successfully expelled an Iraqi invasion force that had occupied neighboring Kuwait, reaffirming international order. However, the nation faced a profound challenge on September 11, 2001, when the pan-Islamist militant organization al-Qaeda launched a series of coordinated attacks on the United States. These devastating events directly led to the initiation of the “war on terror” and subsequent large-scale military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, reshaping American foreign policy and engaging the country in prolonged conflicts abroad.

Domestically, the early 21st century presented significant economic turbulence. The U.S. housing bubble, which had fueled a period of unsustainable growth, culminated in 2007 with the onset of the Great Recession, representing the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression. More recently, the 2010s and early 2020s have been characterized by increased political polarization and what many observers describe as democratic backsliding within the United States. This growing polarization was starkly and violently reflected in the January 2021 Capitol attack, during which a mob of insurrectionists breached the U.S. Capitol building, explicitly seeking to prevent the peaceful transfer of power in what was described as an attempted self-coup d’état, highlighting the profound internal challenges facing the nation’s democratic institutions in the contemporary era.

From its ancient origins to its current complexities, the history of the United States is a narrative of continuous evolution, marked by enduring struggles and remarkable achievements. Each era has laid foundational layers, contributing to a nation that, despite its internal divisions and external challenges, consistently reshapes itself. This historical journey underscores the dynamic interplay of societal ideals, economic forces, technological innovation, and geopolitical shifts that have collectively forged America’s distinctive identity and its ongoing, critical role in the world.