The aspiration of homeownership, long considered a cornerstone of the American Dream, has become increasingly elusive for many, particularly younger generations and the working class. This growing challenge is not merely a consequence of market fluctuations but rather a complex entanglement of economic, social, and policy factors that have progressively reshaped the landscape of housing accessibility. Insights from individuals on the front lines, alongside analyses from economists and policy experts, reveal a nuanced picture of a system under immense strain.

Zachary Foust, a 31-year-old real estate agent in Delaware with over eight years of experience, has gained widespread attention on social media for his impassioned critiques of the current housing market. He initially leveraged TikTok in 2019 to disseminate information about the home-buying process. However, his journey quickly became a stark observation of a troubling trend, as he states, “But slowly but surely, I didn’t realize that I had a VIP front row seat to watching the American Dream get sifted away from the working class.”

Foust articulates a compelling narrative, connecting disparate elements to illustrate how the affluent and influential have systematically exacerbated the difficulties for ordinary citizens to achieve homeownership. He draws a line from the tax cuts initiated during the Reagan administration and the steady ascent of private equity, through the significant market collapse of 2008, to the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision. This landmark ruling, he argues, allowed wealth to exert unprecedented influence over political processes.

These combined factors, Foust contends, have culminated in “the infestation of institutional investors buying up and banking on asset inflation that is housing, that is shelter, keeping normal everyday people out of having a roof in exchange for billionaires having bigger accounts.” This perspective is buttressed by data from the Summer 2025 Investor Pulse Report by BatchData, which indicates that investors accounted for nearly 27% of home sales in the first quarter of this year, representing the highest level observed in the past five years.

In a particularly fervent moment, Foust conveyed his conviction, stating, “It’s clear and evident that the billionaires and trillionaires on this planet are bored because they have everything that they need, yet the ego continues to devour at them and because of pride, because of ego, because of a lust for power. Not only are they trying to financially line their pockets more and more, but they’re doing it to the tune of draining out the bottom of our economy, draining out the working class income, draining out the upper middle class asset opportunity.” He also declared, “I don’t want to just sell homes. I want to start a change for something so that you can get in on the wealth, or we could change the system in some way, all together, promote more equality. Why am I labeled a communist if I want people to have a chance?”

For Foust, real estate transcends a mere transaction; it embodies a fundamental pillar of security. He elaborated that owning a home signifies “a bedrock of protection. It’s a place that you have full ownership of with the people you love, a safe haven that’s truly yours. It’s also an investment that appreciates over time, a foundation of security when everything else in life might feel uncertain.” This deeply personal connection to homeownership has informed his growing disillusionment with his career.

By 2022, Foust observed a disconcerting trend: clients who had diligently followed conventional financial wisdom found themselves unable to purchase homes. He recounted, “The reality hit me when I had clients earning over $100,000 with 700 credit scores, and I still had to walk them through how to prepare to buy a home because they no longer had the freedom to purchase like they once did. Meanwhile, retirees, boomers, and investors (many of whom pay cash) were still buying at a remarkable pace. The market for first-time or working-class buyers stalled, while cash and retirement purchases hardly slowed.”

Despite the formidable financial hurdles confronting the average young American, Foust offers words of encouragement, urging individuals not to abandon their aspirations. He advises, “Take action, even in a tough market. None of us can predict the future, but you can control your financial foundation. Keep debt low and credit high, ideally over 700.” Furthermore, he recommends investing savings into avenues that can yield “4–7% annually to grow your nest egg for a future down payment.”

He also champions unconventional approaches, challenging the prevailing societal expectations of fierce independence. Foust advocates for what he terms “‘homie hacking’ a mortgage together,” stating, “The best advice I’ve given in the past two and a half years is to ignore the stigma around living with family or friends. Living with your parents, family, or a group of friends… is one of the smartest things you can do. It’s awesome. Avoiding rent for a few years to save aggressively?? It can be life-changing.” His own experience of buying his first home profoundly impacted his perspective, describing it as “my wife and my very first nest egg, my first big step into adulthood, and my first real responsibility.”

Beyond individual narratives, the housing industry holds a significant position within the U.S. economy, contributing an estimated 15% to 18% of the Gross Domestic Product annually. Homeownership alone accounts for a quarter of American household net worth, underscoring its pivotal role. Consequently, when analysts and experts allude to a “housing crisis,” it inevitably triggers widespread concern and uncertainty.

John Dunham, a finance expert who previously served as senior economist for both the New York City Mayor’s Office and the New York City Comptroller’s Office, provides a crucial clarification regarding the term. He states, “There is no single economic definition of a housing crisis. Depending on who you are speaking with, it could be a bubble in prices, a lack of supply, a surge in demand, or basically anything that puts the housing market out of equilibrium.” This multiplicity of definitions underscores the multifaceted nature of the problem.

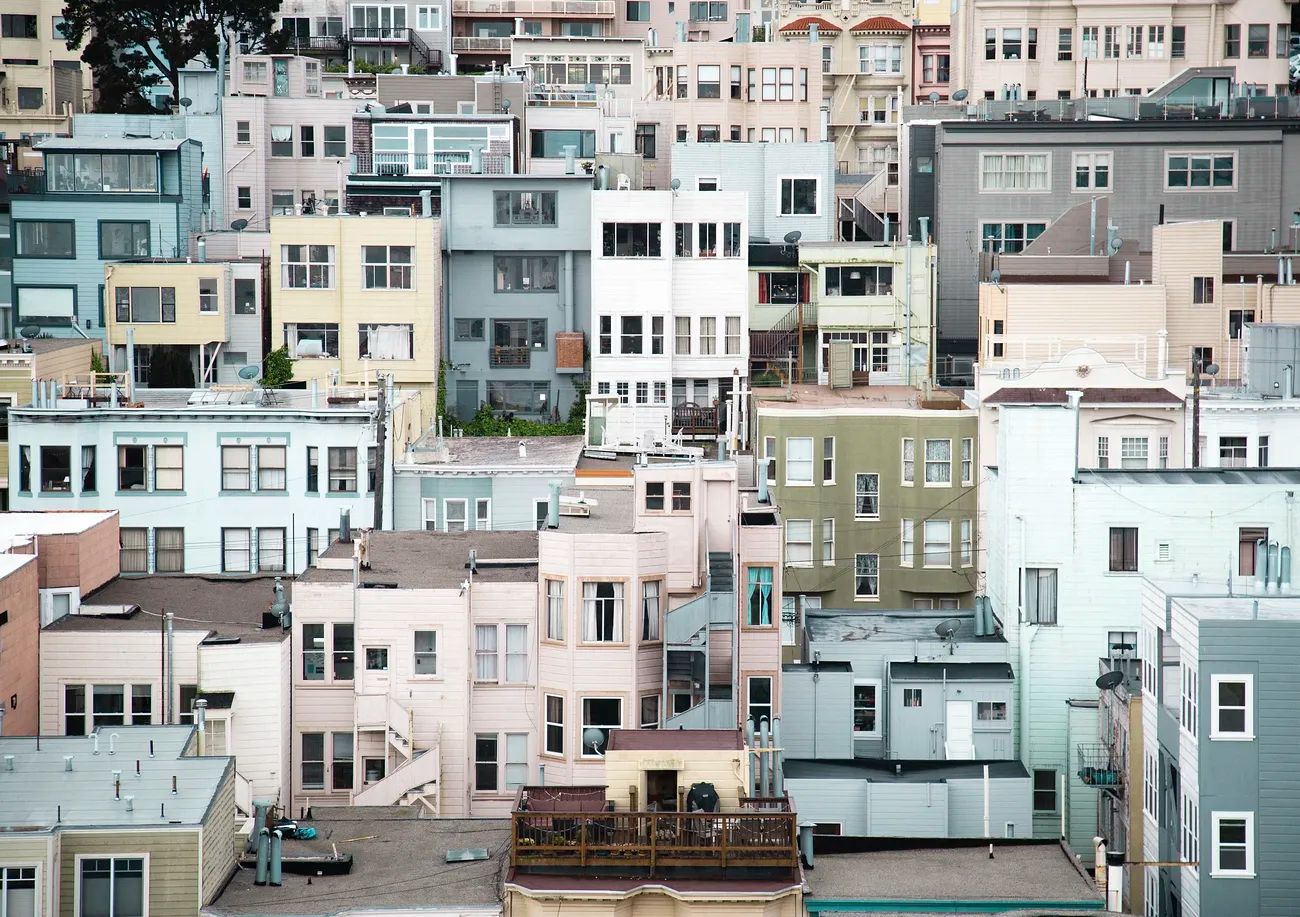

Dunham offers an illustrative example, pointing to the crisis experienced by renters in San Francisco, driven by the escalating cost of rent, where the median asking rent for a one-bedroom apartment reached $3,500 per month. Conversely, in the aftermath of the pandemic and the ensuing urban exodus, San Francisco rents dramatically plummeted by 31%, creating a different kind of crisis—this time for landlords. This demonstrates how the perception of a crisis can shift depending on one’s position within the market.

Several distinct categories define the challenges within the housing market. These include the subprime mortgage crisis, the homelessness crisis, housing disruptions caused by natural disasters, the pandemic rental crisis, and the pervasive chronic housing affordability crisis. Each category presents unique challenges and requires tailored understanding and responses.

The subprime mortgage crisis, often referred to as the 2008 housing market crash, evokes a strong reaction from those who experienced it. The crisis originated when financial institutions eased lending standards, extending subprime loans to borrowers who, under conventional circumstances, would not have qualified. Requirements for down payments and favorable credit scores were significantly relaxed, encouraging a surge in loan approvals and an influx of buyers into the market.

This burgeoning demand fueled a steady climb in house prices, enticing borrowers to undertake high-risk loans with the expectation of future refinancing. However, when home prices plummeted by over 18% in the fall of 2008 and interest rates began to climb, a significant number of homeowners found themselves trapped in unsustainable mortgages, frequently owing more than their homes were worth. Dunham observed, “When demand crashed due to people’s inability to meet their mortgage obligations, the pendulum swung the other way, and there was too much supply chasing too little demand.” The year 2008 alone saw 3.1 million foreclosures filed, equivalent to one out of every 54 homes, resulting in a staggering $3.3 trillion loss in home equity for homeowners.

The homelessness crisis represents a profound societal challenge, affecting individuals across all demographics. The heartbreaking narrative of Miles Oliver, a 55-year-old military veteran in Phoenix, Arizona, illustrates this struggle. When the COVID-19 pandemic halted his pizza delivery shifts, he lost his ability to pay rent and was locked out of his apartment, compelling him to reside in his Ford Fusion. Following a car breakdown months later, Oliver found refuge in a homeless shelter before ultimately securing an apartment through a veterans’ assistance program.

Oliver’s plight is increasingly common among older adults, with a 2019 study of homeless shelters in Boston, New York City, and Los Angeles County projecting a more than threefold increase in elderly individuals forced from their homes over the next decade. John A. Kilpatrick, Ph.D., a certified appraiser with over 30 years of real estate appraisal experience and involvement in homelessness initiatives, emphasizes the complexity of the issue. “There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution to homelessness,” he states, adding, “It’s a very granular problem.”

Kilpatrick elaborates on the diverse circumstances leading to homelessness, citing examples such as intact families seeking rental assistance, single parents grappling with childcare and immediate housing needs, and individuals residing in encampments under bridges, often contending with severe substance abuse issues. He critiques the prevailing approach, noting, “Unfortunately, our cities are all too often set up to deal with this as if it’s a criminal problem (which it is), but not set up to deal with the root-cause social work issue that gives rise to homelessness.” As of January 2018, a White House report indicated that 0.2% of the American population, or 17 out of every 10,000 people, were homeless on any given night, with 65% unsheltered.

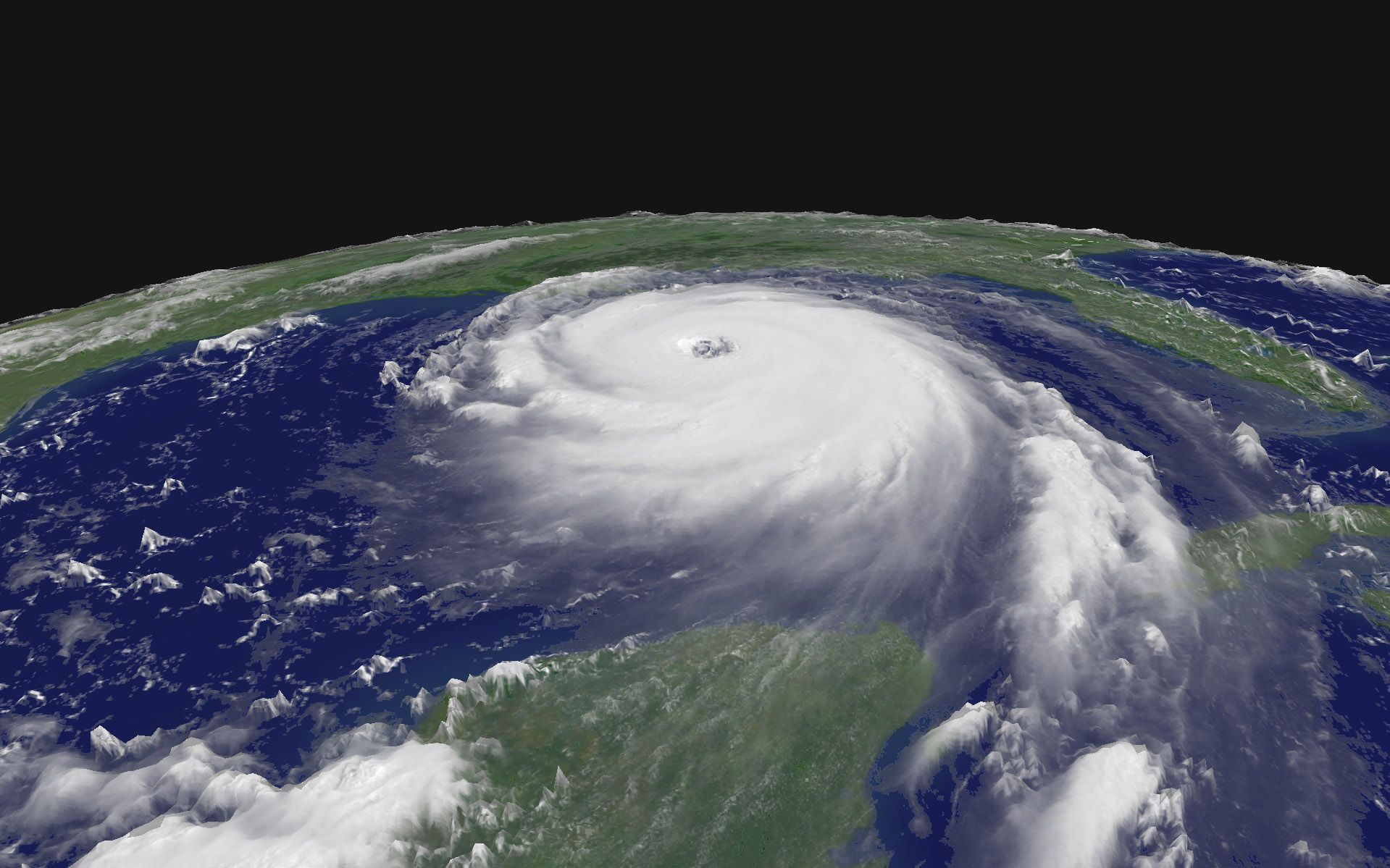

Natural disasters constitute a distinct category of housing crises, unleashing immediate devastation on homes, communities, and livelihoods. These “acts of God,” whether hurricanes, wildfires, floods, or earthquakes, temporarily disrupt real estate transactions. Paradoxically, property values often stabilize or even increase in the aftermath due to the resulting housing shortage.

Hurricane Katrina, which struck on August 23, 2005, damaged one million homes and displaced over a million people. Locally, HomeLight transaction data revealed a near halt in home sales, with only one home sold each week from September 5 to October 5. However, by the week of October 17, transaction volume began to rebound, signaling the city’s gradual recovery. The reduction in New Orleans’ housing supply ultimately led to a 17% spike in home prices between November 2005 and November 2006.

Another consequence of natural disasters is the surge in housing demand and home values in areas adjacent to the affected towns. Displaced residents, once they receive insurance payouts, typically seek resettlement in the same general region. This pattern was observed after a 2018 fire in Paradise, California, which left thousands of families without homes. Six months after the blaze, 1,000 families remained without permanent housing. While home sales in Paradise plummeted by 40% to 50%, sales in unaffected neighboring cities surged, as noted by CoreLogic.

Lynn Peters, a leading real estate agent in Pensacola, Florida, has direct experience with the market’s vulnerability to natural disasters. Her town, having endured Hurricane Ivan in 2004, was struck by Hurricane Sally in September 2020. This storm delivered 25 inches of rain and a five-and-a-half-foot storm surge, bringing the housing market to a near standstill. Peters explains the disruption: “If a home was already listed prior to a disaster, the whole selling process slows down.”

She adds, “If inspections and appraisals were already done, they have to be done all over again. If there is damage to the property, the seller has to file an insurance claim and wait for repairs to be made.” The logistical challenges extend to sourcing experts for repairs, which became prohibitively expensive, slow, or even impossible. Contractors faced immense backlogs, and the high demand for building materials drove construction costs skyward. Peters observed, “Before the storm, if someone needed to replace a roof, it would have cost around $10,000-$15,000. Now, that same roof would cost $18,000-$25,000 to replace. Repairs are also taking up to three times as long to complete.”

The ripple effects of such disasters include prolonged closing delays. Prior to Sally, homes in Peters’ market typically closed within 30 days. Currently, the process extends to at least 45 to 60 days due to backlogs faced by appraisers, inspectors, and other professionals. Furthermore, natural disasters lead to elevated delinquency rates, as income sources dry up, making it difficult for many to meet mortgage payments, even for undamaged properties.

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a distinct rental housing crisis. The onset of the pandemic saw a dramatic surge in unemployment, with 20.5 million job losses and the unemployment rate skyrocketing from 3.5% in February 2020 to 14.7% by April 2020. This abrupt economic contraction spurred speculation of another housing market crash akin to 2008. However, such a crash did not materialize in 2020, largely due to government interventions like the CARES Act, which offered forbearance plans for mortgage holders, preventing a cascade of defaults.

Concurrently, a deficit in new construction, historically low mortgage interest rates, and a surge in home purchases during the pandemic sustained a record-low housing supply. Consequently, the median sale price of existing homes saw a sharp increase of over 15% by October 2020, as reported by the National Association of Realtors. Yet, uncertainties persist, with Peters predicting an increase in distressed sales in her Pensacola market in 2021, driven by the expiration of mortgage forbearances and impending payment deadlines.

The pandemic also brought about uneven demand shifts. Dunham noted that government-imposed shutdowns of major cities made them less conducive to living and working, prompting a migration of middle-class and wealthy individuals toward suburban and coastal areas. This shift has ignited a construction boom and rising prices in these markets, where supply is adapting to demand. While urban housing markets are not necessarily in decline, there has been a notable strengthening of demand for single-family housing across the board, as evidenced by the flood of homebuyers into the Minneapolis market seeking detached homes.

In contrast, the rental market has not fared as well as owned housing post-pandemic, particularly in cities reliant on oil and energy, and major metropolitan areas with a high concentration of professional and technical workers. An analysis from AdvisorSmith revealed significant declines in median asking rent by Q3 2020 in cities such as Odessa, TX (-34.7%), Midland, TX (-30.9%), and San Francisco, CA (-19.1%). Conversely, cities bordering larger metropolitan areas that absorbed urban sprawl experienced rent increases, including Stockbridge, GA (+12.5%) and Avondale, AZ (+11.6%).

Where asking rents have sharply declined, landlords face difficulties covering their mortgages, while in areas of rising rents, unemployed renters struggle to meet their financial obligations. Experts have estimated that between 30 and 40 million Americans could face eviction in the coming months. Kilpatrick underscores the severity for renters, stating, “The pandemic is causing great concern, particularly in the apartment market, as apartment dwellers are disproportionately hit with job loss and rent payment woes.” He further warns that as many apartments are now owned by large REITs and conglomerates, this situation “will inevitably result in availability — and thus affordability — issues down the road.”

Perhaps the most fundamental challenge is the chronic affordability crisis, a pervasive issue that Kilpatrick states has affected the nation for many years. He illustrates this with historical data: in 1970, the average U.S. household income was $8,730, and the average home price stood at $17,000. To qualify for a loan, then, a buyer would typically need a down payment of approximately $5,238, equivalent to about 60% of their annual gross income.

Fast forward to the third quarter of 2020, and the average U.S. household income was $68,400 per year, or around $5,700 per month. Meanwhile, the average home price had soared to $387,000. In this contemporary scenario, a standard 20% down payment would exceed an entire annual household income. Kilpatrick highlights the severity for new buyers, observing, “This situation is even worse among first-time buyers, and builders report record low numbers of first-time buyers in the pipeline.”

The State of the Nation’s Housing 2025 report, published by the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS), reinforces this grim assessment, emphasizing record-high unaffordability and housing sales plummeting to their lowest levels in three decades. The report points to a record number of cost-burdened renters—those dedicating over 30% of their income to housing and utilities—and a substantial increase in cost-burdened homeowners, now totaling 20.3 million households, or 24% of all home-owning households.

This rise in cost burdens for homeowners is partly attributable to escalating insurance premiums and property tax increases, often driven by the increasing frequency of climate-related disasters. These events have compelled private insurers to raise premiums, reduce coverage, and in some instances, withdraw entirely from certain markets. However, the primary catalyst for the affordability crisis remains the soaring cost of homes. Over the last six years, home prices have escalated by 60%, pushing the median existing single-family home price to a record $412,500 last year—a figure five times the median household income, significantly surpassing what is traditionally considered affordable.

Despite the challenges, rental demand remains robust. With fewer households capable of purchasing homes, the renting population expanded by 848,000 in 2024, absorbing the 608,000 new multifamily units completed last year—the highest number in nearly four decades. This trend is exacerbated by an increase in higher-rent units and a reduction in the availability of lower-rent units, further squeezing affordability.

While each housing crisis possesses its unique origins and repercussions, common indicators and pathways to recovery emerge. Lynn Peters, with her 16 years of experience as a Florida real estate agent, identifies core elements that distinguish a housing crisis from a typical market lull: a scarcity of buyers, excessive construction, a decline in home prices, and rising interest rates. Conversely, a housing market recovery is characterized by the availability of affordable mortgages with favorable interest rates, constrained housing inventory, and a simultaneous increase in both home sales and prices.

Peters expresses cautious optimism regarding the future of the housing market and the broader economy, stating, “If interest rates stay low, the economy stays healthy, and we see more businesses open up, I think we will start to see recovery for the overall market.” This hopeful outlook hinges on stable economic conditions and policy adjustments.

Addressing the multifaceted housing crisis necessitates a concerted, comprehensive effort involving governmental bodies, policymakers, and communities. The JCHS report emphasizes that increasing housing supply is crucial, advocating for zoning reforms and revisions to land-use policies at the local level. Additionally, implementing financing tools and design assistance can facilitate the construction of more modestly priced “missing middle” housing types, such as accessory dwelling units and smaller multifamily buildings.

Discussions following the JCHS report’s release highlighted innovative strategies to reduce building costs, including offsite construction, repurposing existing buildings, and creative public land use. Clark Ziegler, Executive Director of Massachusetts Housing Partnership, noted, “The crisis is the mother of invention. Even though it’s a dark time, it’s a time when there’s a lot of creativity flourishing.”

However, significant hurdles impede these efforts. The JCHS report identifies newly imposed tariffs on construction materials, which are estimated to increase the cost of a new home by $10,900. Furthermore, reduced immigration is projected to shrink the already thin labor pool, considering that approximately one-third of construction workers are immigrants. A January NAHB survey also revealed that elevated interest rates (91%), rising inflation (80%), buyer affordability expectations (77%), and the cost and availability of land (63%) are major impediments to increased development.

Chris Herbert, JCHS Managing Director, issued a compelling call to action: “There must be a concerted effort to do more to address the affordability and supply crisis. The potential consequences of inaction are simply too harmful to the macroeconomy and the millions of households striving for a safe, affordable place to call home.” This sentiment is echoed by many who contend that the nation faces a severe housing shortage, with conservative estimates placing the need at 1.7 million units and more liberal calculations ranging up to 7.3 million, with most assessments converging around 4 to 5 million.

This simple narrative—a housing shortage demands more construction—unravels upon closer examination. The root cause of the housing deficit, according to some analyses, is a direct consequence of the real estate industry’s historical influence over the types of housing permitted in the country. This perspective suggests that the current situation stems from treating housing primarily as a commodity for profit, rather than a fundamental need.

Paradoxically, the real estate industry, often vocal critics of regulations like mandatory setbacks, minimum lot sizes, and zoning codes that exclude multiunit properties, is, in effect, protesting a system it helped create and maintain for over a century. This began to take shape in 1922, following World War I, when the federal government initiated campaigns like Better Homes in America (BHA) to foster “a nation of homeowners.”

This movement involved figures like Calvin Coolidge, then Vice President and BHA’s chief adviser, and Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, BHA’s first president, alongside Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then president of the American Construction Council. This “revolving door” between the real estate industry and federal government solidified a vision of homeownership rooted in detached, single-family homes. Hoover framed the concept of “the home as an investment” and a fulfillment of “a primal instinct in us all for homeownership.”

John Ihlder, Director of Housing Conditions for the Chamber of Commerce, reinforced this preference in an article titled “Essentials for Demonstration Home,” asserting that detached, single-family homes surrounded by open space were “the best, unquestionably.” He also outlined minimum setback requirements, which soon became standard. Concurrently, John Gries of the Department of Commerce’s chief division of building and housing emphasized the importance of zoning to create and preserve areas exclusively for single-family homes, shielding them “from invasion by apartments or industry.”

This exclusionary zoning was legally codified in 1926 when the Supreme Court upheld the right of a Cleveland suburb to restrict apartments from single-family areas. From that point, the real estate industry’s mission crystallized around selling the detached, single-family home. During the Great Depression, with cheap land, labor, and federally backed credit, the industry pursued this mission with fervor, evoking parallels to the Manifest Destiny era.

Those who assert that construction alone can resolve the current housing shortage often cite the post-World War II boom as evidence of the market’s ability to meet everyone’s needs. However, this perspective overlooks a crucial reality. While the post-war era did bring rising wages and an increase in homeownership rates for many, it deliberately excluded millions. This group, disproportionately Black but also including non-Black immigrants and a substantial number of white individuals, was denied access to this housing boom.

For these excluded populations, public housing became the primary, albeit often inadequate, option, built and managed by the federal government. From its inception, public housing was structured to operate at a loss. The Housing Act of 1937 stipulated that it would exclusively serve low-income residents, a provision designed to avoid disrupting the profit margins of private developers. Furthermore, the creation of each new public housing unit mandated the demolition of existing “slums,” a concession made to appease cities that held primary oversight over public housing construction.

Public housing remained segregated, and over time, as more white residents secured loans and purchased homes, and housing for Black residents deteriorated, the justification for segregated public housing waned. Vacancies in white public housing increased, while waitlists for Black public housing grew longer. In 1954, the California Supreme Court, in Banks v. Housing Authority of San Francisco, mandated that consistent standards must be applied to all eligible public housing applicants, irrespective of race.

Almost immediately, public housing became politically untenable. Twelve states subsequently enacted constitutional amendments requiring local referendums for the construction of public housing for low-income families, a practice upheld by the Supreme Court. The real estate industry, long an opponent of public housing, seized the opportunity to highlight government expenditures on public housing while obscuring the far more substantial government subsidies that incentivized suburban sprawl.

As these subsidies fostered predominantly white suburban communities, housing prices escalated. Simultaneously, prolonged disinvestment in inner cities created economically depressed areas ripe for redevelopment. Developers and government officials recognized an opportunity to rezone these areas to attract higher-income residents back to urban centers. The resulting displacement of lower-income residents, often people of color, was frequently rationalized as an unfortunate but inevitable consequence of market forces at work.

This dynamic—where some gained valuable assets while others were displaced—became a pervasive analogy for the broader economy as the 1980s and 1990s progressed. Wages stagnated, and wealth inequality, particularly that driven by housing, surged. Economists Lawrence Mishel and Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute observed that “Between 1979 and 2017, the compensation of median workers trailed economywide (net) productivity growth by roughly 43%, leading to rising inequality.” This indicated that while workers were becoming significantly more productive, the economic benefits were increasingly concentrated among a tiny segment of the population.

Navigating the labyrinthine complexities of America’s housing crisis requires an understanding that extends beyond surface-level symptoms. It demands an examination of historical policy decisions, evolving economic paradigms, and the profound human impact of systemic forces. The dream of a safe, stable, and affordable home, once broadly accessible, has become a distant shore for many, caught in currents of rising costs and diminishing opportunities. Yet, amidst these challenges, a collective resolve is emerging—from the impassioned calls of real estate agents to the rigorous analyses of economists and the innovative ideas of urban planners. The path forward is arduous, requiring collaborative action, thoughtful policy, and a renewed commitment to equity. Only by untangling the intricate web of this crisis can we aspire to forge a future where the foundational human right of housing is truly within reach for all, fostering not just shelter, but dignity and prosperity across our communities.