The world of acting, a fascinating blend of history, artistry, and complex industry dynamics, has captivated audiences for millennia. From the solitary figure stepping onto a Greek stage to the global celebrity gracing screens today, the role of the performer has undergone profound transformations, reflecting societal changes, technological advancements, and evolving artistic sensibilities. Understanding this intricate journey requires a deep dive into not just the craft itself, but also the historical context that has shaped its very definition and the people who embody its spirit. This article offers an authoritative and in-depth look into the actor’s profession, meticulously examining its origins, the evolution of its language, and the pivotal moments that have defined its trajectory across different eras and cultures.

As industry observers, we often focus on the glittering facade of entertainment, yet beneath the surface lies a rich tapestry of professional challenges, artistic innovations, and socio-cultural battles. This exploration will illuminate the often-overlooked details of how acting became an esteemed profession, the techniques that empower performers to breathe life into characters, and the economic realities that continue to shape the lives of those dedicated to this demanding art form. It’s a story of constant adaptation, of individuals pushing boundaries, and of an industry striving for authenticity in its portrayal of the human experience.

Our journey begins at the very root of the profession, examining how the terms we use to describe performers came into being, and how historical prejudices and societal norms influenced who could perform, where, and under what conditions. We’ll uncover the surprising origins of ‘actor’ and ‘actress,’ delve into the groundbreaking contributions of early female performers, and trace the path from ancient rituals to the structured, professionalized stage of the modern era. This comprehensive analysis provides crucial insights into the foundational elements that underpin the acting world as we know it today.

1. **The Origin of the Term ‘Actor’: From ‘One Who Does’ to Stage Performer**The word “actor” carries a history far older than its common association with theatrical performance. Initially, its meaning was much broader, signifying simply “one who does something.” This general application prevailed for a significant portion of the English language’s history, reflecting a fundamental human capacity for action and engagement. It was not until the 16th century that this versatile term began to specifically denote individuals who perform in theatre, marking a pivotal moment in the professionalization and recognition of the performing arts. This shift indicates a growing awareness and delineation of the role of the stage performer as a distinct professional identity.

Prior to this specificity, the act of performance, while undoubtedly present, may not have been uniformly categorized under a single, universally accepted professional label. The evolution of the term itself suggests a societal progression where the act of portraying a character for an audience became formally acknowledged as a unique occupation. This linguistic development mirrors the emergence of dedicated theatrical spaces and organized troupes, requiring a precise term to identify those engaged in this particular form of action. It underscores how language adapts to describe emerging social and professional structures.

The adoption of “actor” specifically for theatre performers in the 16th century also highlights the increasing importance and visibility of the dramatic arts during this period. As plays became more popular and accessible, and as professional companies began to flourish, the need for a clear and widely understood term for these practitioners became essential. This semantic evolution laid the groundwork for the rich and complex terminology that would come to define the acting profession, distinguishing it from other forms of doing or creating.

2. **The Contention of ‘Actress’: A Historical Look at Gendered Terminology**The term “actress” has a more recent and often contentious history, first occurring in 1608 and ascribed to Middleton, according to the OED. Its emergence coincides with, and reflects, complex societal views on women in performance. In the 19th century, a period often romanticized for its theatrical grandeur, many still held negative views towards women in acting. Actresses were frequently associated with courtesans and perceived as promiscuous, illustrating the deep-seated prejudices that female performers had to contend with in an era where societal roles for women were rigidly defined.

Despite these pervasive prejudices, the 19th century also paradoxically witnessed the rise of the first true female acting “stars,” with Sarah Bernhardt standing out as a notable example. This period presented a fascinating dichotomy: while the profession for women was often stigmatized, individual talents could transcend these barriers and achieve immense fame and public adoration. After 1660, when women first started appearing on stage in England, the terms “actor” and “actress” were initially used interchangeably for female performers. However, under the influence of the French “actrice,” “actress” became the commonly used term for women in theater and film, a simple derivation from “actor” with the feminine suffix “-ess” added.

In modern times, there has been a significant re-evaluation of gendered professional titles. The re-adoption of the neutral term “actor” within the profession itself dates to the post-war period of the 1950s and ’60s, a time when women’s contributions to cultural life were broadly being reviewed. This movement gained further momentum, exemplified by the 2010 joint style guide of The Observer and The Guardian, which explicitly stated, “Use [‘actor’] for both male and female actors; do not use actress except when in name of award, e.g. Oscar for best actress.” The guide’s authors clarified that “actress comes into the same category as authoress, comedienne, manageress, ‘lady doctor’, ‘male nurse’ and similar obsolete terms that date from a time when professions were largely the preserve of one (usually men).” As Whoopi Goldberg famously articulated, “An actress can only play a woman. I’m an actor – I can play anything,” encapsulating the argument for professional gender neutrality.

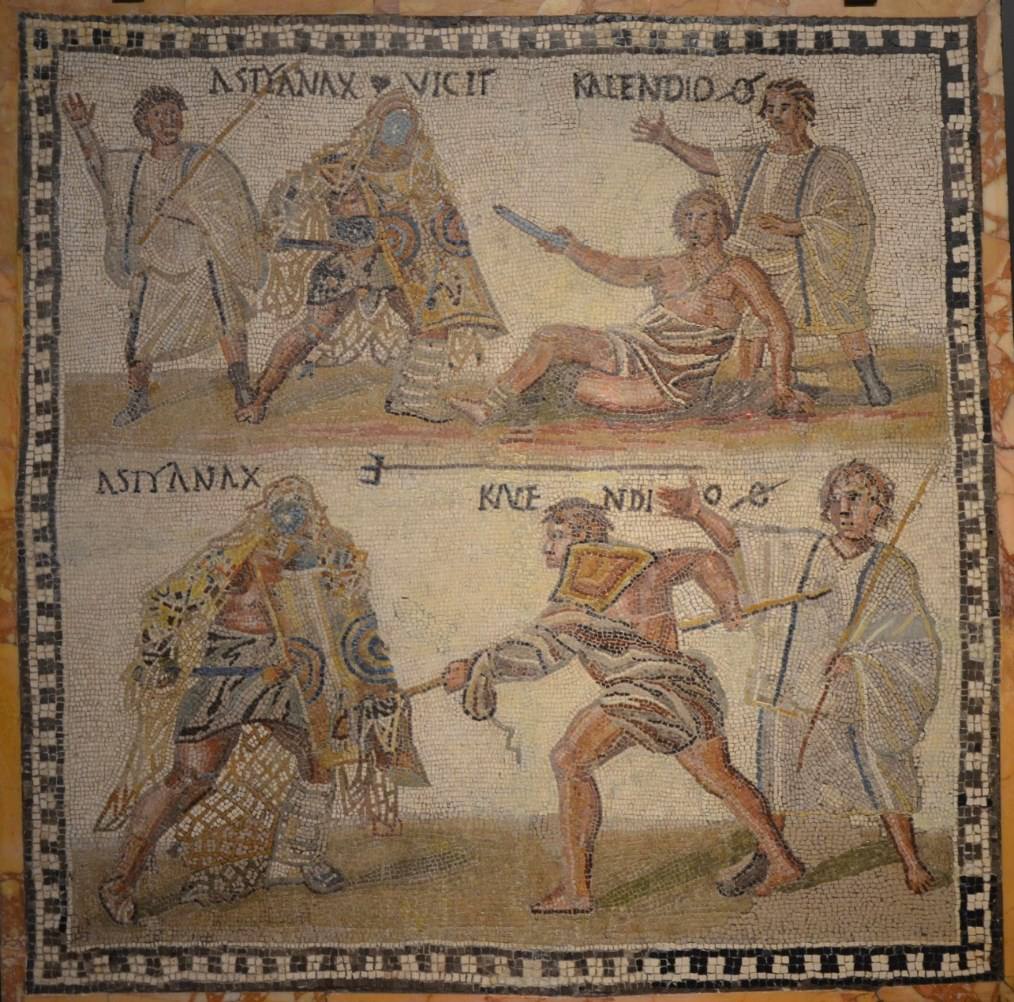

3. **Thespis and the Birth of Performance: Ancient Greek Theatre**The very genesis of Western acting is often attributed to a singular, monumental event that occurred in 534 BC. It was then that the Greek performer Thespis stepped onto the stage at the Theatre Dionysus, embarking on an act that would forever change storytelling. He became the first known person to speak words as a character in a play or story, an innovation that distinguished individual portrayal from the collective narrative. Before Thespis’s daring act, Grecian stories were conveyed solely through song, dance, and third-person narration, lacking the direct, embodied voice of a character.

In recognition of his pioneering contribution, actors today are often affectionately called “Thespians,” a testament to his enduring legacy. This foundational moment established the actor as a distinct entity, a vessel for bringing fictional or historical figures to life through direct speech and action. It created a new dimension in dramatic expression, allowing for deeper character engagement and a more immediate connection between the narrative and the audience. The profound impact of this innovation cannot be overstated, as it set the stage for all subsequent developments in Western theatre.

The exclusively male actors in the theatre of ancient Greece performed in three seminal types of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play. This patriarchal tradition meant that all female roles were also undertaken by men or boys, a convention that would persist in various forms for centuries. The Athenian stage, vibrant and influential, established many of the conventions that would echo through the history of performance, even as the roles and societal standing of its practitioners continued to evolve.

4. **Women on Stage in Antiquity: Roman Exceptions and Medieval Restrictions**While ancient Greece famously barred women from appearing on stage, maintaining an exclusively male acting tradition, ancient Roman theatre presented a notable contrast. Roman stages, vibrant and diverse, did allow female performers, a progressive stance for the era. However, this acceptance came with its own set of limitations. The majority of these female performers were seldom employed in speaking roles, primarily engaged in dancing and other non-verbal entertainments, highlighting a subtle yet significant restriction on their artistic scope.

Despite these constraints, a minority of actresses in Rome did achieve speaking roles and, remarkably, garnered wealth, fame, and recognition for their art. Figures like Eucharis, Dionysia, Galeria Copiola, and Fabia Arete stand out as early pioneers who defied conventional expectations, establishing precedents for female excellence in performance. These trailblazing women even formed their own acting guild, the Sociae Mimae, which was evidently quite wealthy, indicating a degree of professional organization and economic success that challenged the prevailing norms of the time.

As the Western Roman Empire declined, the profession of acting, particularly for women, seemingly faded into obscurity during late antiquity. Throughout the Middle Ages, actors were often viewed with distrust by the Church, denounced as dangerous, immoral, and pagan during the Dark Ages. Traveling acting troupes were nomadic, and in many parts of Europe, traditional beliefs dictated that actors could not even receive a Christian burial. Although medieval theatre did see the rise of liturgical drama and vernacular mystery plays, the performers were typically amateurs, predominantly men, engaged temporarily from church congregations, with women rarely appointed to roles, reflecting a period of severe social and religious restriction on female performers.

5. **The Renaissance Revolution: Commedia dell’arte and Early Professional Troupes**The Renaissance marked a significant turning point for the acting profession, particularly with the rise of professional troupes. Emerging in the mid-16th century, Commedia dell’arte troupes performed lively improvisational playlets across Europe for centuries, revolutionizing the art form. This was an actor-centred theatre, demanding little scenery and very few props, emphasizing the skill and creativity of the performers themselves. The plays were designed as loose frameworks, providing situations, complications, and outcomes around which the actors improvised, showcasing their quick wit and mastery of stock characters.

Crucially, it was in Italy during this period that women first started to appear on stage professionally in Europe. The first professional company of actors since antiquity, whose members are known by name, originated from Padova in 1545. While initially composed solely of men, the landscape soon changed. Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name appears on an acting contract in Rome from October 10, 1564, is often cited as the first Italian actress known by name. Alongside Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia, she represents the first primadonnas and well-documented actresses in Italy and Europe, signaling a monumental shift in who could perform.

From the 1560s onward, actresses became the norm in Italian theaters. When Italian theatre companies toured abroad, these Italian actresses became the first women actors to perform in many countries, exporting this groundbreaking development across the continent. France and Spain also saw women performing on stage during the 16th century, though documentation varies. In Spain, figures like Ana Muñoz and Jerónima de Burgos were active in the 1590s, while in France, despite early activity, individual French actresses were seldom mentioned by name until Marie Vernier emerged as a leading lady and co-director of Valleran-Lecomte’s theatre company around 1604, further solidifying the presence of professional female performers in European theatre.

6. **The English Restoration: Breaking Barriers for Women in Theatre**Compared to much of Western Europe, England was notably late in introducing women onto its public stages. Throughout the first half of the 17th century, a Puritanical opposition to the stage deemed theatre immoral, leading to an eighteen-year prohibition on drama within London. This period saw women’s roles traditionally played by men or boys, even as female actors were emerging in Italy, France, and Spain. The English audience’s first introduction to female actors came through visiting foreign theatre companies, such as the Italian actress Angelica Martinelli in 1578, but these rare occurrences did not lead to a widespread reform allowing native English actresses.

The dramatic shift occurred with the English Restoration of 1660, which saw the lifting of the Puritan prohibition. This pivotal moment signaled a renaissance of English drama, particularly Restoration comedy, which became notorious for its ual explicitness. Most significantly, for the first time, women were formally allowed to appear on the English stage, exclusively in female roles. This period ushered in the introduction of the first professional English actresses and contributed to the rise of the first celebrity actors, marking a profound change in the theatrical landscape.

Margaret Hughes is widely credited as the first professional actress on the English stage. The end of the prohibition against female actors was partly influenced by King Charles II’s personal enjoyment of watching actresses perform. Specifically, Charles II issued letters patent to Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant, granting them the monopoly right to form two London theatre companies for “serious” drama. These patents were reissued in 1662 with crucial revisions that explicitly allowed actresses to perform for the first time, thereby formalizing their place in English theatre and establishing a new era for female performers.

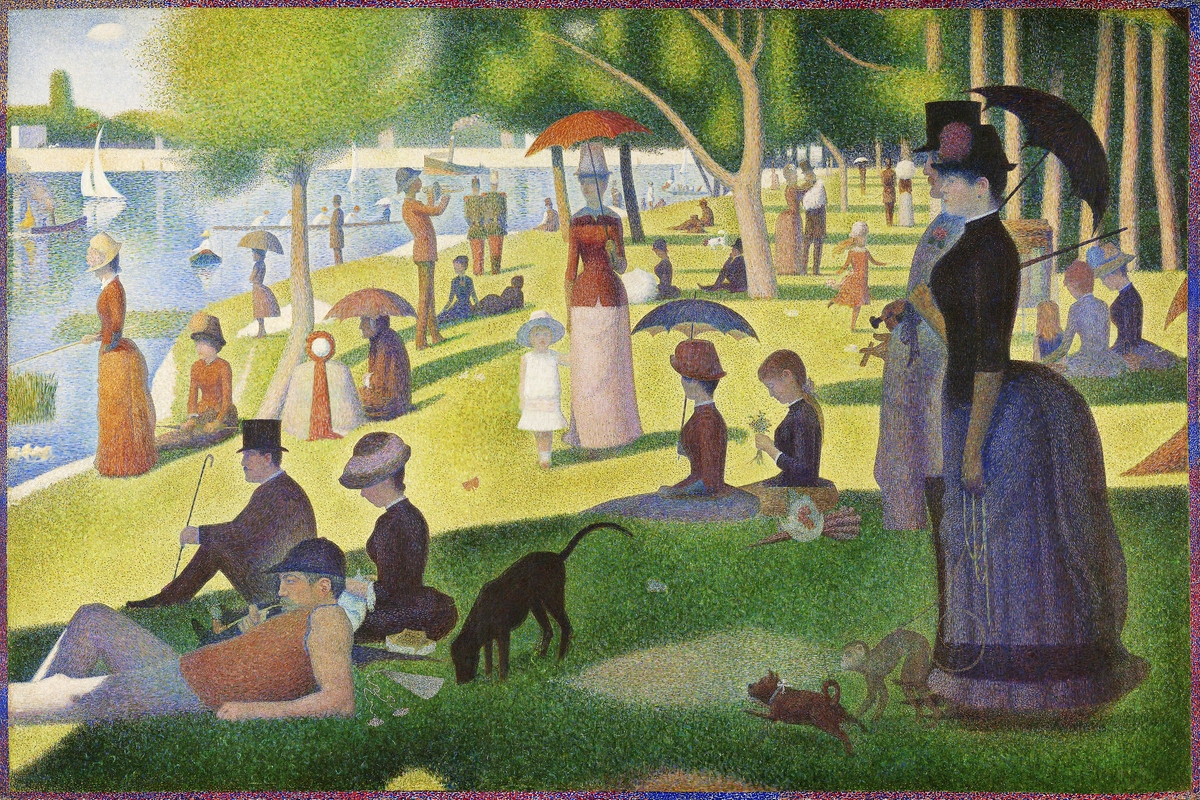

7. **From Disrepute to Dignity: The 19th-Century Professionalization of Acting**The 19th century stands as a transformative era for the acting profession, fundamentally reversing the negative reputation that had clung to actors for centuries. What was once often associated with societal marginalization and moral suspicion evolved into an honored, popular profession and recognized art form. This significant shift was largely propelled by the emergence of the actor as a celebrity, attracting audiences who eagerly flocked to see their favorite “stars” grace the stage. The rise of these charismatic figures cemented acting’s place in public consciousness as a legitimate and glamorous career.

A new and influential role that emerged during this period was that of the actor-manager. These individuals, such as the most successful British actor-manager Henry Irving (1838–1905), formed their own companies, wielding comprehensive control over the actors, the productions, and the essential financing. When successful, they cultivated a loyal and permanent clientele that consistently attended their shows. They further expanded their reach and influence by embarking on national tours, presenting a repertoire of well-known plays, including the works of Shakespeare, to appreciative audiences across the country.

The burgeoning media landscape of the time, including newspapers, private clubs, pubs, and coffee shops, buzzed with lively debates evaluating the merits of the stars and their productions, further fueling public engagement and interest. Henry Irving, renowned for his Shakespearean roles, introduced innovations like dimming the house lights to focus attention on the stage. His company’s tours across Britain, Europe, and the United States powerfully demonstrated the ability of star actors and celebrated roles to draw enthusiastic crowds. His knighthood in 1895 symbolized the ultimate acceptance of the acting profession into the higher echelons of British society, an unprecedented acknowledgment of its cultural significance and dignity.

The journey of acting from ancient rituals to a revered modern profession is a testament to its enduring power and adaptability. As we step into the 20th century and beyond, the industry continued its rapid evolution, embracing new technologies, refining artistic approaches, and confronting persistent societal inequalities. This next section explores the profound shifts that have shaped contemporary performance, from the business structures that govern it to the intricate techniques that empower actors, and the ongoing dialogue around gender representation and economic fairness within this dynamic art form.

We will examine how the entertainment landscape transformed with corporate consolidation, delve into the influential acting methods that define modern character portrayal, and explore the rich history and contemporary relevance of cross-gender acting. Our analysis will also extend to the global contributions of women in theatre beyond the Western sphere, culminating in an examination of the financial realities and systemic disparities, particularly the gender pay gap, that continue to challenge actors in the 21st century. This comprehensive overview aims to provide a clear, objective insight into the intricate workings of the modern acting world.

8. **20th Century Transformation: Corporate Ownership and the Rise of Mega-Stars**The early 20th century heralded a significant shift in the operational dynamics of the entertainment industry, fundamentally altering the actor-manager model that had defined the 19th century. The complexities and financial demands of large-scale productions rendered it increasingly challenging to find individuals capable of combining both acting genius and astute management. This necessity led to a specialized division of labor, giving rise to distinct roles such as stage managers and, subsequently, theatre directors.

Financially, operating out of major cities required substantially larger capital investments. The industry’s solution to this growing need was the emergence of corporate ownership, leading to the formation of chains of theatres. Notable examples include the Theatrical Syndicate, Edward Laurillard, and most prominently, The Shubert Organization. This corporate consolidation centralized power and resources, allowing for more expansive and financially robust theatrical enterprises.

These large urban theatre chains, catering increasingly to tourists, began to favor long runs of highly popular plays, with musicals becoming particularly prominent. In this new commercial landscape, big-name stars became even more essential. Their drawing power was crucial for attracting the large audiences necessary to sustain these prolonged productions, solidifying the celebrity status of actors as a key driver of industry success and profitability.

This era thus cemented the transition from individualized entrepreneurial theatre to a more corporatized, star-driven model, laying groundwork for the modern entertainment behemoth we recognize today across film and television, not just the stage.

9. **The Pursuit of Authenticity: Defining Modern Acting Techniques**The 20th century marked a profound exploration into the craft of acting, giving rise to several influential techniques designed to achieve greater authenticity and depth in performance. Among these, Classical acting stands as a comprehensive philosophy, integrating the expression of the body, voice, imagination, personalization, improvisation, external stimuli, and meticulous script analysis. This approach is rooted in the theories and systems of esteemed classical actors and directors, notably Konstantin Stanislavski and Michel Saint-Denis, offering a holistic framework for artistic expression.

Konstantin Stanislavski’s system, widely known as Stanislavski’s method, revolutionized performance by urging actors to delve into their personal feelings and experiences. The goal was to convey the ‘truth’ of the character they were portraying. This involved actors immersing themselves in the character’s mindset, seeking commonalities between their own lives and the character’s circumstances to deliver a more genuine and believable portrayal, thus forging a deeper connection with the material and the audience.

Building upon Stanislavski’s foundational ideas, Method acting emerged as a distinct range of techniques formulated by Lee Strasberg. Strasberg’s method emphasizes that for actors to develop a deep emotional and cognitive understanding of their roles, they should draw upon their personal experiences to identify intimately with their characters. While sharing roots with Stanislavski’s work, it distinguishes itself in its specific application, though other techniques like those of Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner also stem from Stanislavski’s principles but are not classified as “method acting.”

Sanford Meisner’s technique, for instance, mandates that an actor focus entirely on their scene partner, perceiving them as real and existing solely in that present moment. This approach aims to create a more authentic interaction between actors, making the scene feel genuinely responsive and immediate to the audience. It operates on the core principle that acting finds its most powerful expression in an individual’s genuine response to other people and their immediate circumstances, a direct lineage from Stanislavski’s overarching system.

10. **Breaking the Mold: The Enduring Tradition of Cross-Gender Acting**Cross-gender acting, where an actor portrays a character of the opposite , is a time-honored tradition in comic theatre and film, persisting through centuries and finding new relevance today. The comedic effect generated by an actor dressing as the opposite sex has been a staple, notably in many of Shakespeare’s comedies, which frequently feature instances of overt cross-dressing, such as Francis Flute in *A Midsummer Night’s Dream*. This device continued through cinema, exemplified by Jack Gilford in *A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum*.

Hollywood legends Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon famously donned female attire to evade gangsters in Billy Wilder’s classic *Some Like It Hot*, creating indelible comedic performances. Similarly, cross-dressing for humor was a frequently utilized trope in the beloved *Carry On* film series. Dustin Hoffman in *Tootsie* and Robin Williams in *Mrs. Doubtfire* each starred in hit comedies where they spent the majority of their screen time convincingly portraying women, further demonstrating the enduring appeal of this theatrical convention.

The dynamic of cross-gender acting can become intriguingly complex, as seen in instances where a woman plays a woman pretending to be a man who then, in turn, pretends to be a woman, such as Julie Andrews’ iconic role in *Victor/Victoria*. Gwyneth Paltrow’s portrayal in *Shakespeare in Love* also offered a nuanced take on gender disguise. These layers of obfuscation highlight the artistic potential for exploring identity and perception through performance, transcending simple comedic effect.

Beyond comedy, women playing male roles in film, though less common, have garnered significant critical acclaim. Stina Ekblad’s mysterious Ismael Retzinsky in *Fanny and Alexander* (1982) and Linda Hunt’s Academy Award-winning performance as Billy Kwan in *The Year of Living Dangerously* stand as powerful examples. More recently, Cate Blanchett received an Academy Award nomination for her portrayal of Jude Quinn, a fictionalized version of Bob Dylan, in *I’m Not There*, showcasing the continued artistic merit of women taking on male roles with depth and nuance.

11. **Women on the Global Stage: East Asian and Middle Eastern Contributions**While the Western theatrical tradition grappled with the presence of women on stage for centuries, other cultures developed unique approaches to gender and performance. In Japan, particularly within Kabuki theatre, *onnagata* – men who specialize in playing female roles – became a prominent convention during the Edo period when women were banned from public performance. This tradition continues to be a distinctive and celebrated aspect of Kabuki, demonstrating a distinct cultural interpretation of gender representation in theatre that persists to this day.

Chinese drama, too, showcases diverse traditions in cross-gender casting. In forms like Beijing opera, men have historically performed all roles, including female characters, adhering to long-standing artistic conventions. Conversely, Shaoxing opera often features women playing all roles, including male ones, offering a contrasting example where female performers take on the full spectrum of characters, showcasing their versatility and challenging traditional gendered casting norms within their specific theatrical context.

The Middle East witnessed the emergence of modern theatre during the Tanzimat era in the Ottoman Empire, primarily initiated by Armenian theatre companies in the 1850s. Arousyak Papazian is credited as the first female actor to perform onstage, making her debut in 1857. As conservative societal norms often discouraged Muslim women from public performance, especially due to expectations of harem segregation, the pioneering actors were often Christian Armenians. Actresses like Papazian, due to the severe stigma associated with their profession, often received higher salaries than their male counterparts.

Egypt’s modern theatre, founded in 1870 by Yaqub Sanu, also faced challenges in recruiting indigenous Egyptian female actors, as acting was not considered respectable for Muslim women, who were typically veiled and secluded. Sanu was compelled to employ non-Muslim women, leading to Jewish sisters Milia Dayan and her sister, along with figures like Miriam Samat and Warda Milan, becoming the first actresses in the Arab world. The first Muslim actress in Egypt, Mounira El Mahdeya, did not appear until 1915, underscoring the significant cultural barriers and the gradual, often arduous, path for women to embrace this profession in various global contexts.

12. **Modern Roles for Women: Redefining Performance and Gender Fluidity**In contemporary acting, there’s a growing trend for women to portray characters of boys or young men, particularly within live theatre. This practice is most famously seen in the stage role of Peter Pan, traditionally played by a woman, and in the “principal boy” roles in British pantomime. Similarly, opera features several “breeches roles” – parts where female characters dress as men – which are traditionally sung by women, usually mezzo-sopranos. Iconic examples include Hansel in *Hänsel und Gretel* and Cherubino in *The Marriage of Figaro*.

Beyond traditional instances, modern roles are increasingly being played by actors of the opposite to highlight the gender fluidity inherent in certain characters. A notable example is Edna Turnblad in *Hairspray*, a role brought to life by Divine in the 1988 film, Harvey Fierstein on Broadway, and John Travolta in the 2007 movie musical. These portrayals challenge conventional casting and expand the understanding of character identity, demonstrating that gender expression can be a fluid, performative act.

As non-binary and transgender characters become more prevalent in media, there’s an ongoing discussion about who portrays these roles. While cisgender actors have historically played such characters, for instance, Hilary Swank as Brandon Teena in *Boys Don’t Cry*, the landscape is evolving. Conversely, transgender actors, even before public transition, have played cross-gender roles, such as Elliot Page portraying Shawna Hawkins in the *Tales of the City* miniseries, illustrating the complex and evolving intersection of actor identity and character representation in modern storytelling.

In live theatre, especially for older plays with numerous male characters like Shakespearean works, women frequently take on male roles where gender is inconsequential to the narrative. This not only offers more opportunities for female actors but also brings fresh interpretations to classic texts, further enriching the theatrical experience by challenging traditional casting assumptions and promoting inclusivity within the performing arts.

13. **The Economic Realities of the Acting Profession: Compensation and Career Paths**The profession of acting has always been characterized by a wide spectrum of potential incomes, a reality that persists across centuries and geographic locations. In 17th-century England, some actors, like William Shakespeare during his early career, earned a comfortable income, with his likely wage of 6 shillings per week being comparable to that of a skilled tradesman. This indicates that a stable, albeit not lavish, living was possible for established performers in certain eras.

In contemporary times, the financial landscape remains highly varied. In 2024, the median hourly wage for actors in the United States was $23.33 per hour. However, this median obscures the stark reality that many actors struggle to secure consistent work and essential benefits. A significant challenge for many is the lack of health insurance; only 12.7% of SAG-AFTRA members earned sufficient income to qualify for the union’s health plan, highlighting the precarious nature of acting as a full-time profession.

Similar financial challenges are observed across the Atlantic. Full-time actors in Britain, in the same year, earned a median of £22,500, which is notably slightly less than the minimum wage. This data underscores that despite the visible success of a few, the majority of working actors face considerable economic hurdles, often necessitating supplementary employment to sustain their careers and livelihoods.

Despite these lower median incomes, the profession is also home to individuals who achieve exceedingly large financial success. Global film actors such as Aamir Khan and Sandra Bullock have earned tens of millions of dollars for single film productions, representing the pinnacle of earning potential within the industry. This stark contrast between the median and the highest earners illustrates the highly stratified economic structure of the acting world.

For union child actors in the United States, a daily rate of at least $1,204 is mandated. However, due to their legal status as minors, the majority or all of this income typically goes to their parents or legal guardians. Protective legislation like California’s Coogan Act, and similar requirements in Illinois, New York, New Mexico, and Louisiana, ensure that 15% of a child’s earnings are placed into a blocked trust account, accessible only upon reaching legal adulthood, providing a measure of financial security for these young performers.

14. **Confronting Inequality: The Persistent Gender Pay Gap in Entertainment**The entertainment industry, despite its outward glamour and progressive image, continues to grapple with a significant and persistent gender pay gap. A 2015 Forbes report highlighted a concerning disparity, noting that only 21 of the top 100 highest-grossing films of 2014 featured a female lead or co-lead. Furthermore, women constituted only 28.1 percent of characters in these top films, indicating a clear imbalance in representation that inevitably impacts earning potential and career visibility.

Within the United States, this disparity extends across all scales of salaries, reflecting an industry-wide issue. On average, white women in acting earn 78 cents for every dollar a white man makes. This gap widens considerably for women of color, with Hispanic women earning 56 cents, Black women 64 cents, and Native American women just 59 cents for every dollar earned by a white male actor. These figures starkly reveal intersectional inequalities that compound the challenges faced by female performers.

Forbes’ analysis of US acting salaries in 2013 further underscored this imbalance, determining that the men on their list of top-paid actors for that year earned two and a half times as much money as the top-paid actresses. This means that even among Hollywood’s highest-compensated actresses, their earnings were substantially less than their male counterparts, indicating that the issue is not confined to entry-level or less visible roles but permeates the upper echelons of the industry.

The existence of such a pronounced gender pay gap is a critical issue that continues to be a subject of intense debate and advocacy within the entertainment community. It reflects not only disparities in direct compensation but also deeper systemic issues related to access to leading roles, negotiation power, and prevailing industry biases that undervalue female talent and contribution, despite the undeniable impact and artistry of actresses.

The journey of the actor, from the earliest ‘doers’ to the global stars of today, is a profound narrative of human expression, innovation, and societal change. It’s a testament to the enduring human need for storytelling, for characters who reflect our lives, challenge our perspectives, and offer a window into shared experiences. While the stages and screens have transformed, and the techniques have evolved with remarkable sophistication, the core essence of acting—to embody truth and evoke emotion—remains constant. Yet, this intricate world is not without its ongoing battles, particularly in achieving true equity and fair recognition for all who dedicate their lives to this demanding, beautiful craft. As we look ahead, the story of acting continues to be written, shaped by every performer who steps into the light, every technique that deepens understanding, and every challenge overcome in the pursuit of a more inclusive and authentic artistic future.