Hollywood, a dream factory built on the collective efforts of countless creatives, often shines its brightest spotlight on directors, producers, and the glittering stars gracing the silver screen. Yet, behind the grand narratives and breathtaking visuals, an unsung hero toils in the shadows, meticulously shaping raw footage into cinematic masterpieces. This vital artisan is the film editor, a professional whose craft is not merely assembly, but a brutal, high-stakes process of deconstruction and rebirth, capable of elevating a production from potential disaster to legendary status.

Indeed, the power of the editor is immense, holding the fate of millions of dollars and countless creative aspirations in their hands. In an era where big studio projects command budgets stretching into the hundreds of millions, the pressures on these artists are more intense than ever. While today’s productions often see producers and directors exert firm control from conception to completion, many of our most beloved films once teetered on the precipice of failure, only to be pulled back by the sheer force of an editor’s vision and unwavering dedication.

This intricate dance of cinematic alchemy, where narratives are forged and refined, is particularly pronounced in the realm of summer blockbusters. These films, designed as cultural events to captivate audiences worldwide, demand a singular clarity and impact that often belies the chaotic genesis of their creation. We are about to pull back the curtain on some of these remarkable transformations, exploring how the often-overlooked editor became the unlikely savior of ten famous films, beginning with five tales of extraordinary resilience and creative ingenuity that fundamentally reshaped cinematic history.

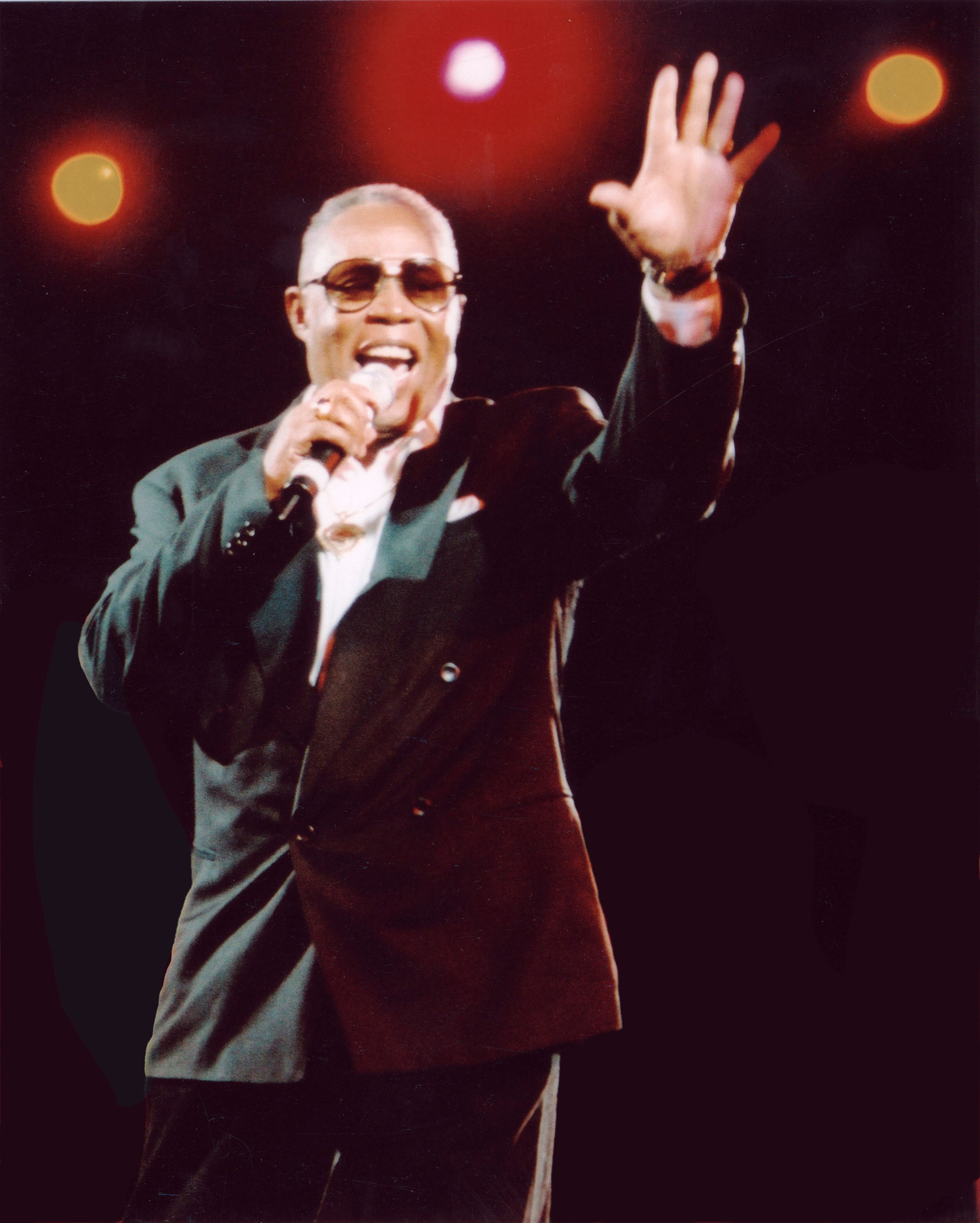

1. **Easy Rider (1969)**

The quintessential American road movie, *Easy Rider*, captured the zeitgeist of the late sixties, placing Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Jack Nicholson at the heart of a journey through counterculture, drugs, and societal confrontation. Conceived by Fonda in a midnight flash of inspiration and swiftly taken on by Hopper to direct, the film was destined to reflect the unconventional spirit of its creators, perhaps a little too faithfully in its initial form.

However, this very adherence to countercultural sensibilities became a significant hurdle in the post-production phase. Neither Fonda nor Hopper possessed the commercial acumen or the ruthless discipline required to carve a mainstream, theater-friendly feature from their artistic endeavor. Influenced by the experimental narrative styles of auteurs like Stanley Kubrick, Hopper’s inaugural cut of the film was a sprawling two hours and forty-five minutes, characterized by a wildly non-linear structure that jumped back and forth through the story with unbridled abandon. Such an unconventional presentation, particularly for a “hippie biker film with an unconventional structure and no plot to speak of,” presented an extremely difficult proposition for commercial distribution.

Recognizing the immense potential buried within this sprawling footage, but also the dire need for structural intervention, the studio took decisive action. Director Henry Jaglom was brought in to collaborate with the astute editor Donn Cambren. Their mission was clear: to distill Hopper’s ambitious, yet unwieldy, vision into a coherent and commercially viable package. Through their collaborative, and no doubt intense, efforts, they managed “to get the film down to the 95-minute mark.”

The result of this rigorous editing was nothing short of miraculous. What emerged was a bona fide piece of cultural and cinematic history, a film that resonated profoundly with audiences and critics alike, earning its place permanently within the cinematic canon. Without the brutal, yet ultimately transformative, editing process led by Jaglom and Cambren, *Easy Rider* might have been consigned to an obscure fate, its powerful message and iconic imagery lost to an unmarketable form. Their work showcased the power of editing not just to shorten, but to fundamentally reshape and elevate a film’s narrative.

Read more about: Beyond the Script: 10 Actors Who Were ‘Wasted’ On Set and Made Movie Magic

2. **Star Wars (1977)**

For generations, *Star Wars* has been synonymous with blockbuster filmmaking, a sprawling saga that has captivated millions. Yet, the legendary status of George Lucas’s original vision was far from guaranteed during its turbulent genesis. Many fans, particularly those who remember the initial theatrical run, have spent years lamenting Lucas’s subsequent “tinkering and CGI interference on every re-release muddied the films’ original vision.” However, a more critical initial threat to the franchise’s very existence came from its first editor, John Jympson.

Jympson’s initial cut of the film proved to be an unmitigated disaster. Following “an unflattering response from Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg to a screening of Jympson’s work,” it became painfully clear that Lucas’s grand space opera was in dire need of radical intervention. The future of a “galaxy far, far away” hung precariously in the balance, threatening to collapse before it had even truly begun.

In response to this cinematic crisis, Lucas assembled a formidable new editing team: Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas, and Richard Chew. These three accomplished editors embarked on a truly monumental task, effectively re-sculpting the entire narrative. Their process involved metaphorical “chopping limbs off the galaxy far, far away,” a stark metaphor for the significant structural changes they implemented. Crucially, they “edited out several sizeable chunks of the first act,” a move designed to streamline the storytelling.

Their collective genius lay in focusing the narrative “in a linear fashion on the space conflict, the droids, and then Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill)—a structure that has been mimicked in mainstream cinema ever since.” Furthermore, thanks to Brian De Palma’s insightful suggestion, this brutal editorial overhaul also birthed one of cinema’s most iconic elements: “the introduction of the iconic opening crawl, which has been climbing into space for 45 years now and shows no sign of stopping.” This relentless dedication to narrative clarity and commercial appeal ultimately saved *Star Wars* and paved the way for an unparalleled cinematic phenomenon.

Read more about: Rewind to Reconsider: 10 Classic Comedies That Would Never Get Greenlit in Today’s Hollywood

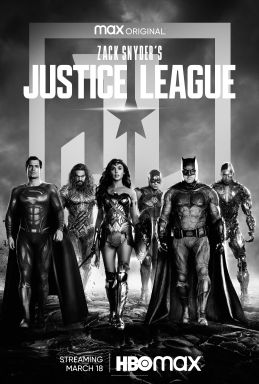

3. **Justice League (2021)**

The journey of 2017’s DC Comics ensemble film, *Justice League*, is a well-documented saga of production woes, editorial conflicts, and fan dissatisfaction. Its original theatrical release was “beset by difficulties throughout production, editing, and release,” largely stemming from director Zack Snyder’s departure during the production phase due to a personal tragedy. His replacement, Joss Whedon, brought a distinctly different “tone and approach,” which regrettably “clashed with Snyder’s vision and led to a choppy post-production process.”

The resulting cinematic Frankenstein was, by all accounts, a “flop.” The disparate creative visions cobbled together in the editing room left “the fans feeling cheated,” sparking an immediate and passionate grassroots campaign for a “Snyder cut.” This was not just a demand for a longer version, but for a fundamental re-imagining, a complete restoration of the original directorial intent that had been fragmented by the conflicting forces of studio intervention and a change in creative leadership.

For three years, this fervent fan movement persisted, a testament to the audience’s belief in an unrealized vision. Eventually, Warner Bros. recognized the undeniable “earning potential of such a move.” Unbeknownst to many, Snyder had continued to work on his own cut of the film privately, collaborating with editor Carlos Castillo. This clandestine effort, a labor of love and artistic conviction, provided the raw material for the studio’s unprecedented decision.

HBO Max, Warner’s video-on-demand arm, stepped in to facilitate the completion of *Zack Snyder’s Justice League*. They meticulously “rounded it off, scored the additional footage, and finished the effects,” transforming a discarded vision into a fully realized epic. In a move that defied “the received wisdom on editing films,” which typically advocates for conciseness, this re-minted version “doubled the original runtime to 242 minutes.” This audacious editorial expansion, a true testament to Snyder and Castillo’s work, not only rescued the film from its initial failure but dramatically “won the hearts and minds of fans across the globe,” demonstrating that sometimes, the most brutal and effective edit is one that adds, rather than subtracts.

Read more about: Lights, Camera, Walkout! 15 Times Directors Ditched Major Blockbusters Mid-Production

4. **Annie Hall (1977)**

Woody Allen’s most enduringly popular film, *Annie Hall*, is a masterclass in comedic drama, renowned for its innovative narrative structure and poignant exploration of relationships. Yet, the film’s celebrated form was far from its initial conception, undergoing a series of radical transformations in the editing suite, a true “comedy of errors befitting Allen’s style” where it was “several different films before it was the one we know.”

The journey to its iconic status began with editor Ralph Rosenblum, who initially took on Allen’s first cut with the challenging aim to “add length, humor, and a sense of life.” However, Rosenblum’s initial efforts, while attempting to imbue the film with vitality, left the film’s writer, Marshall Brickman, with a distinct feeling that the “scope of the feature was too wide and untamed to present as a single, coherent story.” This highlighted the profound struggle inherent in shaping Allen’s typically discursive and introspective cinematic voice into a structured narrative.

Undeterred, and “reckoning the film was so haphazardly plotted that scenes could be chopped and changed at will,” Rosenblum continued his arduous work alongside Wendy Greene Bricmont. Their relentless pursuit of narrative clarity and comedic rhythm, however, led to an unexpected predicament: by the time they believed they were finished, the film surprisingly “only ran to 75 minutes,” significantly falling short of the customary 90-minute benchmark for a standard feature. This underscoring the delicate balance between artistic vision and commercial viability.

With the producers growing increasingly “antsy” over the film’s length and coherence, the editorial team pressed on, “sculpting the existing footage right up until the first proper test screening.” This frantic, last-minute creative burst even included the recording and addition of crucial narration, integrated “just two hours before the film was due to go out.” Against all odds, they “pulled it off,” delivering a film that would not only garner widespread critical acclaim and multiple Academy Awards but also solidify Woody Allen’s distinctive directorial voice, propelling him into an era of prolific filmmaking where he “has made a new film nearly every single year since.” The brutal precision of their editing saved *Annie Hall* from a confusing fate and cemented its place as a genre-defining romantic comedy.

Read more about: Dame Maggie Smith: A Titan’s Farewell – Celebrating the Enduring Legacy of an Unforgettable Stage and Screen Icon

5. **The Thin Red Line (1998)**

Terrence Malick is a director synonymous with an “unorthodox approach to editing,” often “eschewing narrative clarity in favor of spontaneous sequences, thematic overtures, and a distinctly impressionistic, arthouse sensibility.” However, even for a filmmaker known for his unique vision, his late-nineties World War II epic, *The Thin Red Line*, presented an extraordinary challenge, demonstrating a period when his films, through the sheer will of dedicated editors, “trod a slightly more conventional path.”

The sheer volume of footage Malick captured for the film was staggering: “a million and a half feet of film.” This gargantuan amount of raw material, reflective of Malick’s immersive and often undirected shooting style, was the initial mountain that his editing team, Leslie Jones and Billy Weber, had to confront. Their first monumental task was to simply wrangle this vast archive down to a more manageable, though still epic, “initial five-hour cut,” which they “had to force the director to watch.” This colossal undertaking itself required immense dedication and an understanding of Malick’s elusive vision.

The real test of endurance began with the “tortuous editing process” that spanned “the next 13 months of post-production.” Malick’s artistic philosophy, characterized by his “refusal to see the film as a whole” and his insistence “on emotions and sensations taking precedence over structure and plot,” meant his editors faced an uphill battle. The challenge was not just to cut, but to interpret and impose a narrative framework onto a director’s deeply impressionistic raw material. This intense period of refinement eventually necessitated the involvement of a fourth editor, Saar Klein, to help navigate the immense complexities.

Working around Malick’s resistance to conventional storytelling, Klein, Jones, and Weber collectively engaged in an almost architectural task, “hammering each scene into place to create a digestible whole.” Their collaborative and persistent efforts were crucial in bridging the gap between Malick’s profound, yet diffuse, artistic impulses and the need for a coherent, engaging cinematic experience. While Malick’s subsequent films have indeed “untethered further from typical editing conventions,” becoming “ever-more niche and splitting audiences down the middle,” the invaluable “input enabled *The Thin Red Line* to become a critical darling and fan favorite,” a testament to the brutal yet masterful editorial work that transformed a director’s sprawling vision into a universally lauded masterpiece.

Continuing our journey through the crucible of post-production, we now turn our gaze to five more harrowing editing sagas, demonstrating with vivid clarity how editors defied studio demands, directorial challenges, and technological limitations to craft enduring cultural phenomena and redefine genre filmmaking. These are tales of vision, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of cinematic perfection, often under the most brutal of pressures. The editor, it becomes ever clearer, is not merely a technician but an architect of dreams, capable of turning chaos into coherence and potential failure into legendary triumph.

Read more about: A Deep Dive: The Luxury Vehicles That Lose Value Fastest and Why Owners Are Furious

6. **Men in Black (1997)**

Barry Sonnenfeld, a director celebrated for orchestrating big-budget successes throughout his career, encountered few productions as fraught with tension and last-minute interventions as the inaugural *Men in Black* in the late 1990s. This sci-fi comedy, destined to launch a global franchise, faced a dramatic upheaval not in the early stages, but when the finish line was tantalizingly close.

With just two weeks remaining before the movie was to be scored, Sony, the powerful production company, delivered a bombshell: they deemed the existing narrative “too complicated.” This unexpected pronouncement signaled a desire to fundamentally alter the entire plot, a move that typically sends shockwaves through any creative team, especially at such a critical juncture. The studio’s inherent inclination to protect its colossal investment often supersedes artistic integrity, making such demands unavoidable.

In this high-stakes scenario, the task of re-sculpting the film fell squarely upon the shoulders of editor Jim Miller. He embarked on an exhaustive re-edit, meticulously re-ordering scenes, integrating new footage to align with the studio’s eleventh-hour directives, and even modifying the subtitles for alien dialogues to suit the radically new narrative trajectory. This was not a subtle tweak but a comprehensive overhaul under immense pressure, a testament to Miller’s ability to adapt and execute.

Ultimately, Sony’s bold, if somewhat audacious, gambit paid off handsomely. *Men in Black* exploded at the box office, grossing nearly $600 million worldwide and catapulting its star, Will Smith, into household-name status across the globe. The film’s success transcended its theatrical run, spawning an animated series, three sequels, six video games, and an array of branded tie-ins, cementing its place as a cultural phenomenon and a stark reminder of the editor’s capacity to pivot a production to victory.

Read more about: 15 Movie Character Deaths That Hurt Most: Unforgettable Moments With Wheeljack’s Passing & Casper’s Farewell

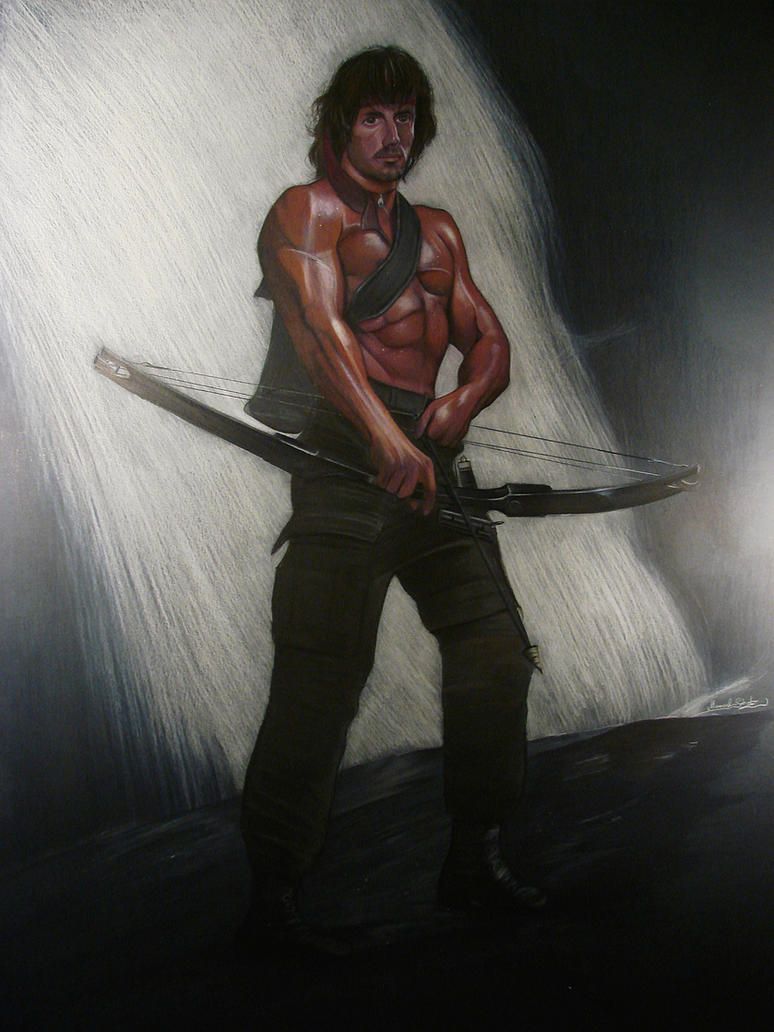

7. **First Blood (1982)**

While *Rocky* indelibly etched Sylvester Stallone’s name into cinematic lore, it was *First Blood* that truly forged his identity as an iconic action hero. This intense thriller, now widely recognized as *Rambo: First Blood*, didn’t just establish a five-film franchise spanning four decades; it critically cemented Stallone’s formidable presence within the realm of “cheesy, over-the-top, action genre classics,” shaping his career trajectory for years to come.

However, the path to the screen for *First Blood* was riddled with formidable obstacles, particularly within the cutting room. The initial assembly of the film clocked in at an unwieldy three and a half hours, characterized by a sluggish pace and a distinct lack of engagement that left not only Stallone but also his agent and the studio deeply dissatisfied. The situation was so dire, in fact, that Stallone, fearing for his nascent career, attempted the drastic measure of buying back the film rights solely to destroy it.

It was this profound crisis that necessitated a brutal, yet utterly transformative, editorial intervention. The sprawling epic was mercilessly trimmed down to a lean and impactful 93 minutes, roughly half its original runtime. This extensive editing process also crucially included a drastically altered ending, which ingeniously left Rambo’s fate ambiguous, paving the way for future installments and adding an unforeseen depth to the character’s legacy.

This courageous editorial decision proved to be an overwhelming triumph, both critically and financially. Against a modest $14 million budget, *First Blood* amassed an impressive $125 million at the global box office. The editor’s decisive actions not only saved the film from oblivion but also sculpted a tightly paced, thrilling narrative that resonated deeply with audiences, laying the groundwork for one of cinema’s most enduring action heroes.

Read more about: Beyond VHS: 15 ’80s Cult Classics That Still Spark Debate and Define an Era

8. **The Limey (1999)**

Steven Soderbergh’s neo-noir crime thriller, *The Limey*, stands as a fascinating artifact from a pivotal phase in the director’s career. It represents a curious middle period, a bridge between the independent, deeply personal cinematic explorations like *Kafka* and *Sex, Lies, and Videotape* that first garnered him acclaim, and the subsequent foray into big-budget, mainstream blockbusters like *Ocean’s Eleven* that would ultimately ensure his enduring longevity in Hollywood.

Despite its foundations in Lem Dobbs’s conventionally structured screenplay, Soderbergh and his trusted editor, Sarah Flack, faced a stark and disheartening realization after filming and completing their initial cut: they had, by their own assessment, produced a “dud.” This moment of creative crisis prompted a radical re-evaluation, forcing them to confront the film’s inherent flaws and the limitations of its straightforward narrative presentation.

Undeterred by this setback, the visionary pair embarked on an audacious and painstaking endeavor: to reconstruct the entire film from scratch. They courageously jettisoned the conventional structure in favor of a non-linear approach, a bold decision that granted them the creative latitude to entirely remix and redefine the feature. Through this transformative process, they were able to artfully conceal narrative deficiencies, amplify the film’s core conceptual explorations of the past and memory, and, crucially, imbue the narrative with the thematic tension that had been conspicuously absent in the original version.

While *The Limey* received only a limited theatrical release, its innovative editing and profound narrative depth have garnered it cult classic status in the years since. It is now widely regarded as an essential, intricate piece in the complex puzzle of Soderbergh’s distinguished filmography, a testament to the power of relentless re-imagination and the editor’s capacity to breathe new life into an ailing project, creating a lasting artistic legacy.

Read more about: Beyond the Leads: 15 Scene-Stealing Supporting Performances That Undeniably Outshined the Stars

9. **Blade Runner (1982)**

Ridley Scott’s *Blade Runner*, a cinematic adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s seminal sci-fi novel *Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?*, seemed beleaguered from its very inception. The production was marred by palpable tensions between director Scott and his lead actor, Harrison Ford, which complicated on-set dynamics. Further, persistent squabbling between Scott and the studio culminated in a theatrical cut that left virtually no one satisfied, signaling deep discord within the creative process.

The film’s initial theatrical run was unequivocally disappointing, failing to recoup its production budget and relegating it to the annals of potentially forgotten cinema. Its eventual ascent to iconic status was not a product of immediate critical or commercial success, but rather the fortunate outcome of a confluence of serendipitous events that unfolded gradually over the ensuing years, breathing new life into a nearly discarded masterpiece.

The pivotal turning point arrived in 1990 when, almost by accident, a rough, unapproved cut of the film was publicly screened at the Fairfax Theatre in Los Angeles. This version, rife with significant differences from the universally maligned theatrical release, evoked an overwhelmingly positive response from the audience. Galvanized by this unforeseen reaction, Warner Bros. took the extraordinary step of commissioning a new cut, meticulously supervised by archivist Michael Arick and meticulously aligned with Scott’s original notes, directorial intent, and editing preferences.

The director’s cut, released in 1992, profoundly altered several key facets of the film, most notably excising Ford’s infamously lackluster narration that had burdened the original. This definitive version achieved widespread critical acclaim and unprecedented mainstream success, belatedly recognizing *Blade Runner* as a visionary masterpiece. This editorial rebirth solidified its place in cinema history, unequivocally demonstrating that a film’s true potential can sometimes only be unlocked through a brutal, yet precise, re-examination of its very essence.

Read more about: Beyond VHS: 15 ’80s Cult Classics That Still Spark Debate and Define an Era

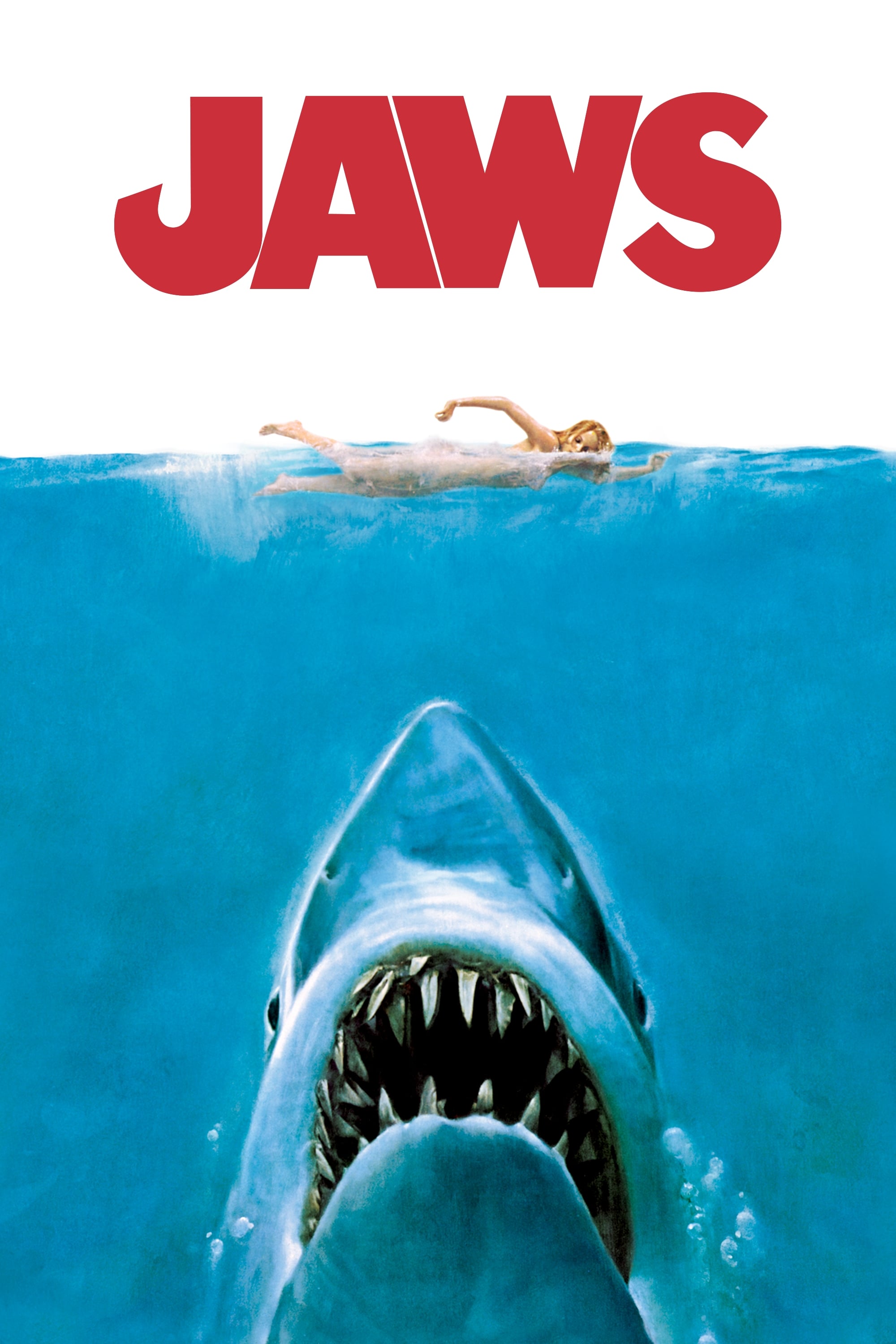

10. **Jaws (1975)**

Steven Spielberg’s *Jaws* is rightfully hailed as the film that not only launched his illustrious career but also singularly pioneered the modern blockbuster genre, breaking ground as the very first film to breach the $100 million mark at the box office. Yet, this monumental triumph, a cornerstone of cinematic history, very nearly remained an unrealized vision, teetering precariously on the brink of disaster during its tumultuous production.

The unparalleled success of *Jaws* is often attributed to the masterful scarcity of its titular villain—the shark itself—which famously enjoys a mere four minutes of screen time within the film’s two-hour duration. This deliberate restraint, widely lauded as shrewd filmmaking for its tension-building prowess, was, in a twist of fate, anything but by design. The animatronic props available to the production team were, by contemporary standards, woefully inadequate, rendering the raw footage of the full creature horrifyingly fake and utterly unconvincing.

It was in this critical predicament that the genius of editor Verna Fields became the film’s undeniable savior. Fields made the executive, and profoundly courageous, decision to systematically remove virtually all footage that explicitly showcased the entire creature. Instead, she artfully crafted sequences relying on the unsettling imagery of churning water, fleeting glimpses of semi-submerged fangs and fins, and, most iconic of all, the now-classic POV shark shot to convey the beast’s terrifying presence, transforming a technological limitation into an artistic strength.

Fields’s monumental contribution not only salvaged *Jaws* from almost certain failure but, by all accounts, fundamentally transformed the landscape of horror cinema forever. Her innovative editing propelled popular horror filmmaking away from the often-cheesy tropes of Hammer horror flicks, laying the indelible groundwork for a new era of dark creature features like *Alien* and igniting the slasher boom that commenced with *Halloween*. Even as John Carpenter famously expresses his disinterest in Spielberg’s work, the profound influence of *Jaws* and its brutal, brilliant editing on his genre-defining film remains an undeniable truth of cinematic lineage.

Read more about: Beyond Horror: An In-Depth Look at Stephen King’s Unexpected Top 10 Films of All Time

As we conclude this exploration of the brutal editing processes that rescued some of cinema’s most beloved blockbusters, it becomes abundantly clear that the film editor is far more than a technician. They are the unseen heroes, the final architects of narrative, the alchemists who transform raw, often unwieldy, material into gold. Their unwavering dedication, often against daunting odds and conflicting visions, underscores a fundamental truth: behind every cinematic triumph, there lies a story of meticulous cuts, bold decisions, and the relentless pursuit of perfection in the editing suite. These unsung saviors, with their brutal precision, ensure that the magic of the movies endures, captivating audiences for generations to come.