The medieval period. Just saying the words conjures images of valiant knights in shining armor, imposing castles on dramatic hilltops, and sweeping sagas of kings and queens, often set against a backdrop that feels simultaneously epic and, well, a little bit grim. Hollywood, with its endless appetite for historical drama and fantasy, has given us countless interpretations of this thousand-year epoch, from grand epics like “Kingdom of Heaven” to gritty thrillers and romantic adventures. We love these films, and for good reason—they transport us to a world that feels both familiar and wildly different.

But here’s the thing that often gets lost in the cinematic grandeur: a lot of what we see on screen, while entertaining, is frequently, demonstrably, and sometimes hilariously wrong. As fans, we often crave accuracy, or at least a reasonable approximation of it, to truly immerse ourselves in the historical fabric. When movies take too many liberties, or worse, perpetuate long-debunked myths, it can pull us right out of the experience, leaving us wondering what the real Middle Ages were actually like.

That’s where we come in. Forget the historical inaccuracies that are just minor plot holes; we’re diving deep into the fundamental misunderstandings that permeate popular medieval cinema. Get ready to challenge everything you thought you knew, because we’re about to expose 15 common movie blunders regarding knights, castles, and culture that historians—and increasingly, discerning fans—simply can’t abide. This first section will tackle the foundational myths, pulling back the curtain on the “Dark Ages” and showing how much more complex and vibrant the start of this era truly was.

1. **The Monolithic “Middle Ages” Myth: Why One Size Doesn’t Fit All in Medieval Cinema** One of the biggest pitfalls many medieval movies fall into is treating the entire 1000-year span of the Middle Ages as a single, undifferentiated bloc of history. You’ve seen it: characters, technology, and societal norms that feel like they’ve been pulled from a grab bag of “medieval stuff” and thrown together without much regard for chronology. The reality, as historians understand it, is far more nuanced, with distinct periods that underwent radical transformations in politics, society, and culture.

The context explicitly outlines these divisions, stating that “The medieval period is itself subdivided into the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages.” This isn’t just an academic nicety; these periods, spanning roughly from the 5th to the 15th centuries, were as different from each other as, say, the Victorian era is from the roaring twenties or the modern digital age. The Early Middle Ages, for example, were characterized by the “collapse of centralised authority, invasions, and mass migrations of tribes,” quite distinct from the “significant” population increase, flourishing trade, and founding of universities seen in the High Middle Ages.

Filmmakers who ignore this periodization risk creating anachronistic hodgepodges where 12th-century knights might wield 15th-century weapons, or early medieval peasant life is depicted with the trappings of the Late Middle Ages. It’s crucial to remember that a knight from the time of Charlemagne would have lived in a world vastly different from one who fought in the Hundred Years’ War. Understanding these internal divisions is the first step to accurately portraying the incredible complexity and evolution of medieval Europe, making our cinematic journeys through time far more authentic and engaging.

2. **The “Dark Ages” Misconception: Unveiling the Light in Europe’s Early Medieval Period** For far too long, popular culture has embraced the notion of the “Dark Ages” as a period of absolute intellectual and cultural stagnation following the fall of Rome. This trope, perpetuated by many films, paints a picture of widespread illiteracy, scientific regression, and a general gloom that enveloped Europe for centuries. The term itself, as the context explains, has its roots in Petrarch’s 14th-century view, where he “regarded the post-Roman centuries as ‘dark’ compared to the ‘light’ of classical antiquity.” However, modern historians have largely abandoned this blanket term, restricting its use to only the Early Middle Ages, and even then, with significant qualifications.

The reality is that the break with classical antiquity was never truly complete. While “population decline, counterurbanisation, the collapse of centralised authority, invasions, and mass migrations of tribes” certainly marked the Early Middle Ages, the flame of classical learning and Roman institutions never entirely flickered out. The still-sizeable Byzantine Empire, “Rome’s direct continuation,” survived in the Eastern Mediterranean, remaining “a major power” and a beacon of classical knowledge. In the West, “most kingdoms incorporated the few extant Roman institutions,” demonstrating a significant degree of continuity rather than utter collapse.

Furthermore, the context highlights that “monasteries were founded as campaigns to Christianise the remaining pagans across Europe continued.” These monasteries became vital centers of learning and preservation, where “many of the surviving manuscripts of the Latin classics were copied.” Far from being intellectually barren, this era saw “intellectual efforts … towards imitating classical scholarship” and the creation of “some original works,” with figures like Bede contributing significantly. Therefore, movies that paint the entire early medieval period as uniformly ignorant miss the intricate ways knowledge was preserved and adapted, and the nascent cultural developments that were quietly taking root.

3. **”Barbarian Invasions” as Pure Destruction: The Nuance of Migration and Cultural Fusion** Hollywood often loves a good rampaging horde, and medieval movies frequently depict the “barbarian invasions” as purely destructive military campaigns, with savage tribes overwhelming the remnants of Roman civilization and utterly obliterating anything in their path. Think hordes of Vandals or Goths simply burning and pillaging without purpose. While there was certainly violence and disruption, this cinematic simplification misses the profound complexity of what the context describes as “large-scale movements of the Migration Period.”

The text clarifies that these were “not just military expeditions but migrations of entire peoples into the empire.” These were communities, often fleeing other pressures (like the Huns in the case of the Goths), seeking new homes and lands. The “movements were aided by the refusal of the Western Roman elites to support the army or pay the taxes that would have allowed the military to suppress the migration.” This highlights a more intricate dynamic than simple conquest. Furthermore, the relationships were not always purely adversarial.

Crucially, the context notes that “Intermarriage between the new kings and the Roman elites was common,” leading to “a fusion of Roman culture with the customs of the invading tribes.” Even material artifacts show this blend, with “tribal items often modelled on Roman objects.” The new “Frankish, Alemanni, and the Burgundians all ended up in northern Gaul” and “Angles, Saxons, and Jutes settled in Britain,” forming new kingdoms. This wasn’t just destruction; it was a complex process of demographic shift, cultural exchange, and the birth of new societies from the ashes of the old, a far more interesting and historically rich narrative than mere barbaric devastation.

4. **The Disappearance of Roman Law and Order: How Roman Legacy Endured in New Kingdoms** Many cinematic depictions of the post-Roman world often imply a complete collapse of any semblance of organized governance, law, and administrative structures. Once the last Western Roman Emperor is deposed, it’s often shown as a descent into utter chaos, with law being purely arbitrary and local. However, the historical reality, as detailed in our context, paints a much more resilient picture of Roman institutional survival and adaptation within the newly formed “barbarian kingdoms.”

The text explicitly states that “most kingdoms incorporated the few extant Roman institutions.” This means that while centralized Roman authority vanished, local Roman administrative practices, legal principles, and even some aspects of infrastructure often continued to function, albeit in modified forms. The new rulers, often of non-Roman background, recognized the utility and efficacy of many Roman systems, adapting them to their own burgeoning polities rather than completely discarding them. This ensured a degree of continuity in legal and administrative practices, preventing a total institutional vacuum.

Furthermore, the context highlights the enduring power of Roman legal tradition in the East, with the “Corpus Juris Civilis or ‘Code of Justinian’,” a comprehensive codification of Roman law, being “rediscovered in Northern Italy in the 11th century.” This rediscovery later had a profound impact on the development of European legal systems. Even in the West, “much of the scholarly and written culture of the new kingdoms was also based on Roman intellectual traditions.” Therefore, movies that portray a complete and immediate erasure of Roman law and order after the 476 AD milestone miss the critical ways in which these foundational elements persisted, evolved, and shaped the emerging medieval world.

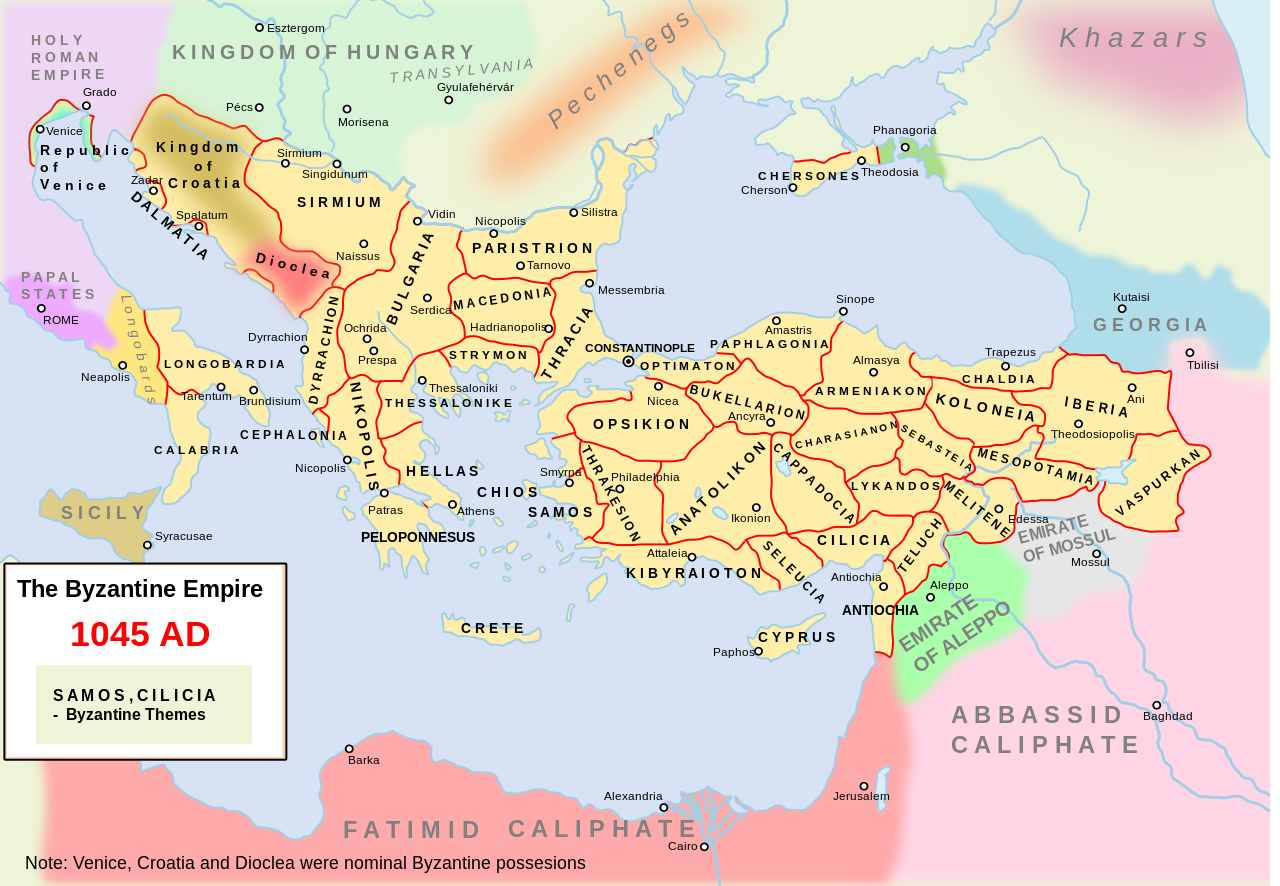

5. **The Ignored Byzantine Empire: The Enduring Powerhouse Hollywood Overlooks** When filmmakers turn their attention to the Middle Ages, particularly the early centuries, their gaze is almost exclusively fixed on Western Europe. This singular focus often means that one of the most significant, enduring, and direct continuations of the Roman Empire—the Byzantine Empire—is either completely ignored or relegated to a mere footnote. This omission is a major historical disservice, as the context clearly establishes the Byzantine Empire’s immense importance.

The text unequivocally states that the “still-sizeable Byzantine Empire, Rome’s direct continuation, survived in the Eastern Mediterranean and remained a major power.” While Western Europe was experiencing fragmentation and the formation of new kingdoms, the Eastern Roman Empire “remained intact and experienced an economic revival that lasted into the early 7th century.” It faced fewer invasions, maintained “closer relations between the political state and the Christian Church,” and most notably, was the crucible of immense legal developments, including the “codification of Roman law; the first effort—the Codex Theodosianus—was completed in 438.”

Under Emperor Justinian, the monumental “Corpus Juris Civilis” was compiled, and Constantinople, with its architectural marvels like the Hagia Sophia, stood as a glittering testament to Roman power and culture. The Byzantines even attempted reconquests of lost Western territories, like North Africa and Italy. To depict the entire medieval world without acknowledging this powerful, sophisticated, and culturally rich empire is to present an incomplete and distorted view of the historical landscape. It’s a glaring oversight that dramatically diminishes the true scope and interconnectedness of the post-classical world.

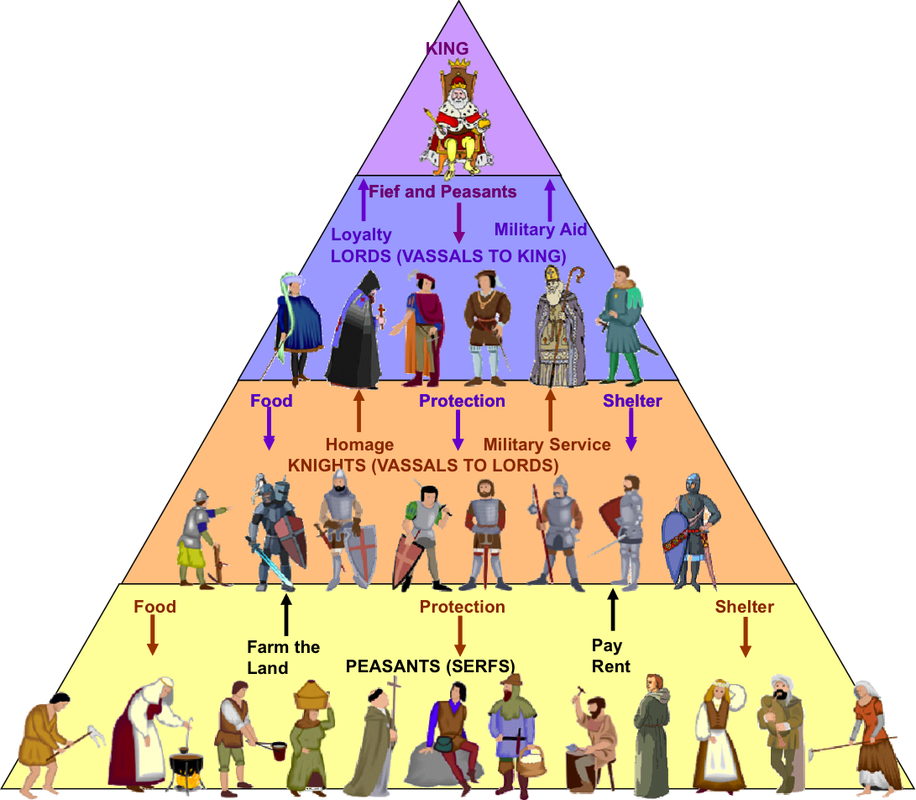

6. **Feudalism and Manorialism as Universal, Static Systems: Unpacking Their True Scope** Few concepts are more entrenched in popular medieval imagery than “feudalism,” often presented in films as a rigid, unchanging system that governed every aspect of medieval life from the fall of Rome to the Renaissance. Knights, lords, and peasants are invariably shown locked into a timeless pyramid of loyalty and service. However, the context provides a far more precise and limited understanding of these complex social and economic arrangements, primarily situating them within a specific period.

The text notes that “Manorialism, the organisation of peasants into villages that owed rent and labour services to the nobles, and feudalism, the political structure whereby knights and lower-status nobles owed military service to their overlords in return for the right to rent from lands and manors, were two of the ways society was organised in the High Middle Ages.” The key phrase here is “High Middle Ages,” which began “after 1000.” This immediately refutes the idea that these systems were universal across the entire thousand-year span.

Furthermore, the context describes them as “two of the ways society was organised,” implying that other forms of social and political organization existed, and that even where they did exist, their application would have varied significantly by region and time. Movies often simplify these complex, evolving relationships into a monolithic structure, overlooking the regional variations, the fluid nature of power dynamics, and the fact that these systems developed over centuries, rather than being established fully formed at the start of the medieval period. To truly grasp medieval society, one must appreciate the dynamic and often localized nature of these arrangements, rather than imposing a single, static model.

7. **The Myth of a Unified Christendom: When East and West Diverged** Many medieval movies, particularly those set after the early centuries, often operate under the assumption of a single, unified Christian Church across all of Europe. Whether depicting devout commoners or powerful bishops, the implication is a singular, Western-centric religious authority. This perspective entirely overlooks one of the most monumental and enduring schisms in Christian history, a division that fundamentally reshaped both religious and political landscapes: the East–West Schism.

Our context explicitly highlights this pivotal event: “The Early Middle Ages witnessed the rise of monasticism in the West… Increasingly, the Byzantine Church differed in language, practices, and liturgy from the Western Church.” This divergence wasn’t just superficial; “The Eastern Church used Greek instead of Western Latin.” More profoundly, “Theological and political differences emerged, and by the early and middle 8th century, issues such as iconoclasm, clerical marriage, and state control of the Church had widened to the extent that the cultural and religious differences were more significant than the similarities.”

The text then clarifies the eventual breaking point: “A formal break known as the East–West Schism came in 1054, when the papacy and the patriarchy of Constantinople clashed over papal supremacy and excommunicated each other, which led to the division of Christianity into two Churches—the Western branch became the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern branch the Eastern Orthodox Church.” Any film portraying a unified Christendom after 1054, especially during the Crusades (which involved both branches), is significantly misrepresenting a core aspect of medieval European identity and geopolitical dynamics. The presence of two distinct Christian powers, often at odds, adds a layer of complexity that is too often ignored in cinematic portrayals.

8. **The Simplistic View of the Crusades: More Than Just Holy War**Movies often distill the Crusades into a straightforward narrative of devout Christian knights battling ‘infidels.’ While religion was a powerful motivation, this portrayal simplifies a far more complex historical phenomenon, steeped in political maneuvering, economic ambition, and shifting alliances that went beyond mere piety. Our context details multi-faceted events with intricate causes and consequences.

‘The Crusades, first preached in 1095, were military attempts by Western European Christians to regain control of the Holy Land from Muslims.’ However, the High Middle Ages also saw ‘Kings became the heads of centralised nation-states.’ This meant secular rulers had their own agendas, using Crusades for ambitious nobles or to expand influence. Expeditions offered opportunities for personal gain and national prestige beyond spiritual salvation.

Crucially, the Crusades were not simply about Christians versus Muslims. The East–West Schism of 1054 ‘led to the division of Christianity into two Churches.’ Relations between Western Crusaders and their Byzantine Orthodox counterparts were often strained, sometimes hostile, culminating in the Fourth Crusade’s sack of Constantinople. This internal Christian conflict undermines the cinematic myth of a unified crusading movement, missing geopolitical reality.

9. **The Medieval World as Illiterate and Unintellectual: Celebrating Scholasticism and Universities**A persistent myth in medieval cinema is the portrayal of the entire thousand-year period as an intellectual wasteland, with unlettered knights and uninterested nobility. This ignores the vibrant intellectual renaissance of the High Middle Ages, where ‘scholasticism, a philosophy that emphasised joining faith to reason,’ flourished alongside the revolutionary founding of universities.

The context explicitly highlights that ‘Intellectual life was marked by scholasticism… and by the founding of universities.’ These were centers of advanced learning where scholars rigorously debated philosophy, theology, law, and medicine. Figures like Thomas Aquinas, whose ‘theology’ is cited as an ‘outstanding achievement,’ epitomized the era’s rigor. The existence and growth of these universities demonstrate a profound commitment to knowledge and inquiry Hollywood rarely acknowledges.

Furthermore, while the Early Middle Ages saw a decline in classical scholarship, it was far from a total blackout. The context notes that ‘monasteries were founded’ and ‘many of the surviving manuscripts of the Latin classics were copied in monasteries.’ Monks like Bede ‘authored new works.’ This preservation laid the groundwork for a genuine intellectual explosion, making cinematic depictions of universal ignorance a gross misrepresentation of a sophisticated and evolving scholarly tradition.

10. **The Black Death’s Underestimated Impact: Confronting Europe’s Greatest Demographic Catastrophe**While some medieval films nod to hardship or plague, they rarely convey the true, catastrophic scale of the Black Death. Often, it’s a plot device rather than the seismic societal shift it was. The reality of this pandemic, as detailed in our context, was far more devastating than commonly depicted, fundamentally reshaping Europe in ways no other event managed. It wasn’t just an illness; it was an existential crisis.

The context outlines the horrifying impact: ‘between 1347 and 1350, the Black Death killed about a third of Europeans.’ This staggering figure, tens of millions of deaths, wasn’t a temporary inconvenience. It was a demographic collapse that rippled through every layer of society, from peasant to nobility, touching every family and community.

Such massive loss of life had profound economic, social, and cultural consequences. Labor shortages dramatically altered power dynamics. ‘Peasant revolts’ during the Late Middle Ages were exacerbated by the upheaval. The psychological impact, questioning of faith, and long-term shifts in land use and economic opportunities were all direct results of this plague, shaping the character of the Late Middle Ages in ways a simple cinematic montage cannot convey.

11. **Economic Anachronisms and Ignored Realities: The True Cost of Medieval Life**Medieval movies often assume a familiar economic system, despite realities being vastly different from modern capitalism. Films frequently get fundamentals wrong, from goods flow to wealth concepts. Our context provides crucial insights into the rudimentary economic realities constraining medieval society, especially in the early period.

‘Migrations and invasions of the 4th and 5th centuries disrupted trade networks around the Mediterranean.’ ‘African goods stopped being imported into Europe, by the 7th century, found only in a few cities.’ This drastic contraction meant ‘Replacing goods from long-range trade with local products was a trend.’ It wasn’t a vibrant globalized economy; it was largely localized and self-sufficient.

Currency and exchange were distinct. ‘Gold continued to be minted until the end of the 7th century… when it was replaced by silver in the Merovingian kingdom.’ The ‘basic Frankish silver coin was the denarius or denier.’ ‘No silver coins denominated in multiple units were minted,’ and ‘Copper or bronze coins were not struck.’ This highlights a monetary system focused on small, silver denominations. Movies often impose modern value understanding, missing the challenging logistics of a largely agrarian, localized economy.

12. **The Homogenous, Oppressed Peasantry: Diversity and Mobility in Rural Europe**No group is more consistently misrepresented in medieval movies than the peasantry. They are almost universally portrayed as a homogenous, downtrodden mass, perpetually toiling in squalor under their lord. This cinematic trope ignores the incredible diversity, varying degrees of autonomy, and potential for social mobility within medieval peasant society, particularly in the Early Middle Ages.

Our context provides a vital corrective: ‘Peasant society is much less documented than the nobility.’ Yet, archaeological evidence and few written records reveal variations. ‘Landholding patterns in the West were not uniform.’ Some areas had fragmented land, others large blocks. This led to ‘a wide variety of peasant societies, some dominated by aristocratic landholders and others having great autonomy.’ Not all peasants were equally oppressed.

The idea of a fixed class structure is challenged. ‘Unlike in the late Roman period, there was no sharp break between the legal status of the free peasant and the aristocrat, and a free peasant’s family could rise into the aristocracy over several generations through military service to a powerful lord.’ This detail reveals social fluidity rarely seen in films. The medieval countryside was a mosaic of dynamic social and economic arrangements, far more than a uniform sea of serfs.

13. **Vibrant, Clean Medieval Cities: The Reality of Urban Contraction and Resourcefulness**Hollywood often presents medieval cities as bustling, vibrant hubs, thriving centers of commerce and culture, echoing later urbanism. The reality, especially in the Early Middle Ages, was far more complex and involved significant contraction from Roman predecessors. The idea of ‘clean’ medieval cities is a modern misconception, but even the scale and function of these urban centers are frequently misunderstood.

Our context makes it clear: ‘Roman city life and culture changed greatly in the early Middle Ages.’ ‘Italian cities remained inhabited, they contracted significantly in size.’ Rome, for instance, ‘shrank from hundreds of thousands to around 30,000 by the end of the 6th century.’ This was a dramatic demographic and structural shrinkage. ‘In Northern Europe, cities also shrank, while civic monuments and other public buildings were raided for building materials.’ This indicates urban decay and repurposing.

However, it wasn’t total abandonment. ‘Roman temples were converted into Christian churches and city walls remained in use.’ ‘The establishment of new kingdoms often meant some growth for the towns chosen as capitals.’ While some cities declined, others adapted or emerged as new political centers. The true medieval city, particularly in the early centuries, was a testament to resourcefulness and adaptation, often smaller, more fortified, and less focused on grand public works.

14. **The Limited Role of Elite Women: Power and Influence Beyond the Conventional Gaze**Cinematic portrayals of elite women in the Middle Ages often swing between two extremes: passive ladies-in-waiting or anachronistically empowered warrior queens. While rare historical counterparts exist, movies frequently miss the nuanced, informal, yet significant ways elite women wielded power and influence within patriarchal societies. Our context reveals a more complex picture, particularly in their roles within families and religious institutions.

The text states that ‘Women took part in aristocratic society mainly in their roles as wives and mothers of men, with the role of mother of a ruler being especially prominent in Merovingian Gaul.’ This highlights the crucial, indirect power women could exert through their sons. A queen mother, acting as a regent or powerful advisor, could significantly shape political decisions and court intrigues. This was not always overt political power, but it was undeniably influential, demonstrating agency beyond mere decoration.

Furthermore, the context expands on women’s roles in Anglo-Saxon society: ‘In Anglo-Saxon society, the lack of many child rulers meant a lesser role for women as queen mothers, but this was compensated for by the increased role played by abbesses of monasteries.’ Abbesses were powerful figures, managing extensive estates, holding sway over spiritual and temporal affairs, and providing patronage. These positions offered avenues for authority and leadership distinct from male-dominated political roles. To reduce elite medieval women to simplistic stereotypes overlooks their ingenious ways of navigating and influencing their world.

15. **The Myth of Universal Slavery’s Decline: Labor Dynamics in a Changing Europe**Many films depict medieval society transitioning entirely from ancient slavery to serfdom, with outright slavery being a relic. While slavery evolved and declined, its universal disappearance is a cinematic oversimplification. Our context, particularly regarding the Early Middle Ages, indicates a more complex and persistent reality of unfree labor, demonstrating that slavery continued, albeit in altered forms and with shifting dynamics.

The text notes a crucial detail: ‘Slavery declined as the supply weakened, and society became more rural.’ This acknowledges a decline, implying it didn’t vanish entirely, but changed. The shift towards a more rural society, combined with transformed political structures and a move away from Roman taxation, would alter demand and supply for traditional slavery. However, ‘declined’ is not the same as ‘disappeared.’

Moreover, while traditional chattel slavery diminished, various forms of unfree labor emerged, often grouped under serfdom. These systems involved significant restrictions on personal liberty, labor services, and obligations to lords, blurring the lines of ‘freedom.’ The context also hints at continued trade, mentioning Franks traded ‘enslaved people in return for silks and other fabrics, spices, and precious metals from the Arabs’ by the mid-8th century. This shows that even as internal dynamics shifted, external trade in humans continued, proving that slavery remained a part of the medieval economic and social fabric.

There you have it: 15 crucial ways Hollywood often misses the mark when bringing the Middle Ages to life. From the Byzantine Empire’s reach to the intellectual vibrancy of universities, and from urban contraction to the impact of widespread disease, the medieval period was a tapestry woven with more complex threads than our screens show. By understanding these historical nuances, we can critique films with a keener eye, gaining a richer appreciation for an era anything but dark or simplistic. The real Middle Ages, in all their glorious, messy complexity, offer a treasure trove of stories waiting for accurate portrayal.