For over six decades, the James Bond franchise has delivered an indelible brand of cinematic espionage, thrilling audiences with its blend of sophisticated action, exotic locales, and a protagonist who always seems to glide through peril with effortless cool. Yet, before Bond even utters his first quip or seduces his latest target, viewers are drawn into his world by a foundational, instantly recognizable flourish: the gun barrel sequence. This brief, powerful opening has become as much a part of 007’s identity as his Aston Martin or his preference for a shaken-not-stirred martini. It’s a testament to brilliant design, a psychological prelude that primes the audience for the thrills to come.

This iconic sequence, far from being a static entity, has undergone its own subtle but significant evolution, adapting to new actors, changing film technologies, and shifting cinematic styles. It’s more than just an intro; it’s a carefully crafted piece of film history that tells a story in mere seconds, establishing mood, character, and the ever-present danger that defines Bond’s world. The way Bond walks, turns, and fires, all from the perspective of an unseen assailant, is a masterclass in visual storytelling, rooted in a simple yet profound technique.

Today, we’re taking a deep dive into the fascinating world behind Bond’s legendary entrance. We’ll peel back the layers of this cinematic cornerstone, examining how its original concept came to life, how various actors — from stuntmen to leading men — have lent their unique physicality to the ‘walk,’ and the technical innovations that brought it to life. This isn’t just about a cool visual; it’s about the deliberate choices and creative genius that forged a signature moment in film history, influencing everything that followed. Let’s unpack the enduring power of the gun barrel sequence, one frame at a time.

1. **The Genesis of the Walk: Maurice Binder’s Rapid Concept**The story of the iconic gun barrel sequence begins not with meticulous planning over months, but rather with a stroke of genius born out of a tight deadline. Maurice Binder, the visionary behind the opening titles of the inaugural Bond film, *Dr. No* in 1962, found himself in a rush. He had a meeting with the producers looming, a mere twenty minutes away, and needed to conjure an opening that would instantly define the new spy franchise. This pressure cooker environment led to a remarkably simple yet profoundly effective idea that would echo through cinematic history.

Binder himself recounted the genesis of the sequence, explaining, “That was something I did in a hurry, because I had to get to a meeting with the producers in twenty minutes.” It was in this flurry of creative urgency that the core concept of Bond’s iconic walk and shot materialized. He improvised, grabbing readily available materials to visualize his idea. “I just happened to have little white, price tag stickers and I thought I’d use them as gun shots across the screen.” This impromptu tool became the visual foundation for the distinctive white dot that would traverse the screen, hinting at the lethal ballet about to unfold.

The concept swiftly moved from simple stickers to a fully fleshed-out storyboard. Binder envisioned James Bond making his entrance, walking across the screen, before suddenly turning and firing directly at the camera. The immediate, visceral consequence of this act would be a red blood wash, symbolizing the assailant’s demise, running down the screen. This rapid conceptualization, sketched out in about twenty minutes, was then presented to the producers. Their reaction was immediate and overwhelmingly positive: “This looks great!” It’s a classic Hollywood tale of a last-minute idea becoming an enduring legend, a testament to Binder’s innate understanding of visual impact and narrative economy.

This initial, hurried design laid down the immutable laws of the gun barrel sequence: Bond’s entrance from the side, his decisive turn, the shot fired directly at the audience, and the subsequent blood-red curtain. It was a narrative compression, a micro-story that communicated danger, precision, and Bond’s lethal effectiveness without a single word. Binder’s quick thinking not only solved a pressing production need but also gifted the world of cinema one of its most recognizable and effective opening motifs, setting the stage for every Bond film thereafter with an unparalleled sense of anticipation and style.

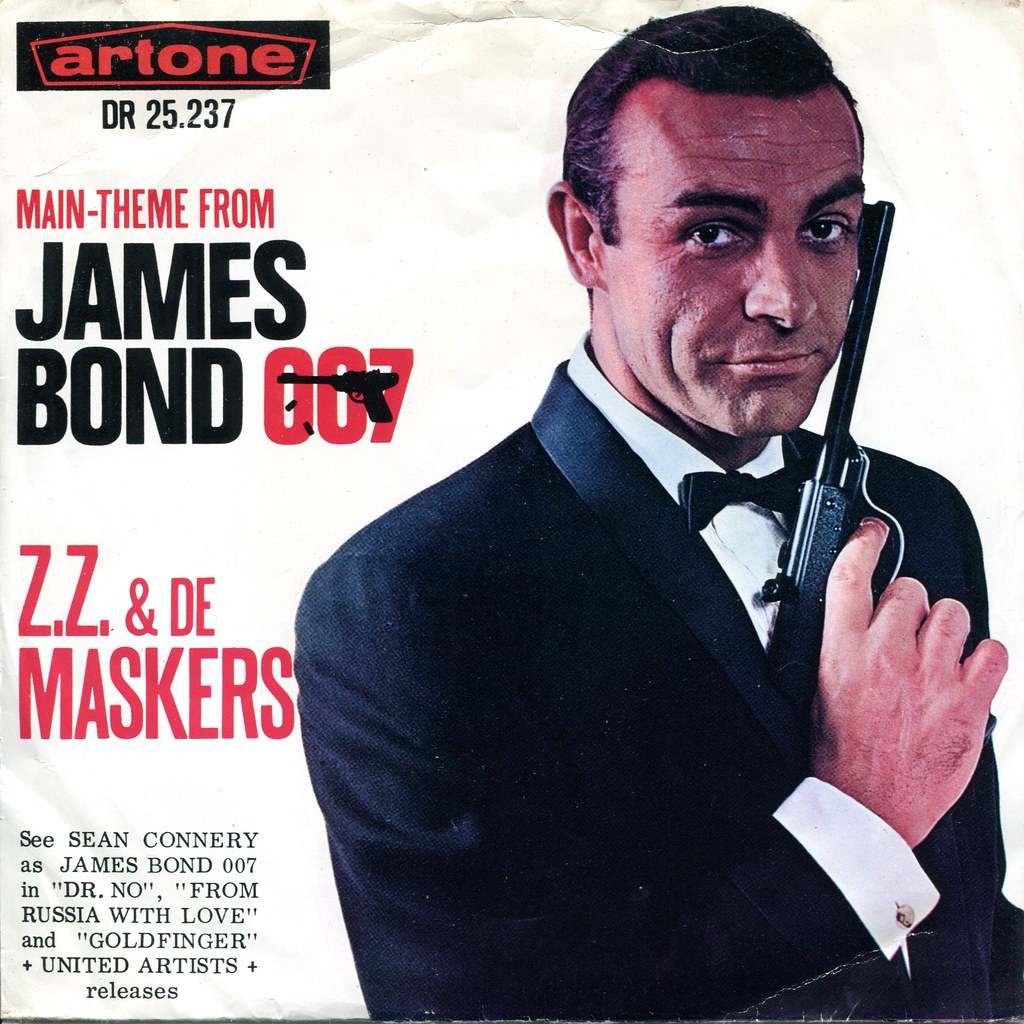

2. **The Inaugural Stunt: Bob Simmons’s Silhouette Performance (1962-1964)**When Maurice Binder first designed the gun barrel sequence for *Dr. No*, his intention was for James Bond to appear in silhouette, a shadowy figure against a neutral background. This stylistic choice, coupled with the non-widescreen aspect ratio of the early films, meant that the leading actor, Sean Connery, was not actually needed for the shoot. Instead, a capable stand-in was employed to bring Binder’s vision to life, embodying the nascent character’s physical presence before his face was ever fully revealed.

That pivotal role fell to stuntman Bob Simmons. Simmons was the first to perform the now-legendary walk, stepping into the formidable shoes of James Bond, albeit in a shadowed, almost anonymous capacity. His rendition of the walk established the foundational movements that future Bonds would iterate upon. The camera would track him as he walked from right to left, a figure of purpose and latent threat, until he reached the center of the frame, pausing before his decisive turn.

Simmons’s performance in these early sequences possessed its own distinct nuances. The context notes that he “hops slightly as he pivots to assume the firing position.” This subtle detail, a brief moment of dynamic movement before the static aim, added a unique characteristic to the very first iconic walk. Following his shot, the familiar red blood wash cascaded down the screen, a chilling confirmation of the sequence’s deadly intent. The white dot, which initiates and concludes the sequence, also had a specific behavior in this initial iteration: after the blood wash, it “becomes smaller and jumps to the lower right-hand corner of the frame before simply vanishing.”

In *Dr. No*, there were additional distinctive elements to this first sequence. The white dot momentarily halted mid-screen to display the credit line “Harry Saltzman & Albert R. Broccoli present,” a clear marker of the producers’ introduction. This text would then be wiped away, allowing the dot to continue its journey and the sequence to resume. Accompanying these visuals was a unique soundscape, featuring “electronic noises and then numerous notes that sound like they are being plinked from a wind-up jack in the box,” abruptly cut short by the gunshot. This early version, with its specific movements and audio cues, established the blueprint for all subsequent gun barrel sequences, setting a high bar for an iconic opening.

3. **Technical Mastery: The Pinhole Camera’s Role in Clarity**The creation of the gun barrel sequence was not merely an artistic endeavor; it also presented significant technical hurdles. Maurice Binder’s vision of a camera sighted directly down the barrel of a .38 calibre gun was groundbreaking, but its execution required innovative problem-solving. Capturing the intricate details of the rifled interior while maintaining a sharp focus throughout the entire length of the barrel proved to be a formidable challenge for standard cinematic equipment of the era. The very essence of the sequence – the illusion of looking *through* the weapon – depended on achieving this visual clarity.

Binder quickly encountered the limitations of conventional filmmaking. A standard camera lens, he discovered, simply couldn’t achieve the depth of field necessary to bring both the immediate foreground of the barrel and its distant interior into sharp focus simultaneously. “Unable to stop down the lens of a standard camera enough to bring the entire gun barrel into focus,” the conventional approach was failing. This technical snag threatened to compromise the very impact of the sequence, which relied heavily on the stark, stark visual of the weapon’s interior to convey menace and precision.

However, Binder was not one to be deterred by technical difficulties. Instead, he devised an ingenious solution that bypassed the limitations of existing camera technology. He “created a pinhole camera to solve the problem,” an elegant and surprisingly simple workaround. A pinhole camera, known for its infinite depth of field, was perfectly suited to the task, allowing the entire length of the gun barrel to appear “crystal clear.” This innovation was crucial, transforming a conceptual design into a tangible, high-impact visual that would become synonymous with the franchise.

The successful deployment of the pinhole camera ensured that the gun barrel itself became a character in the sequence, a menacing tunnel that the audience metaphorically entered before Bond’s appearance. The six-sided rifling, similar to that of a .38 calibre gun barrel, was rendered with striking clarity, adding an extra layer of authenticity and detail. This technical mastery, achieved through creative problem-solving, was just as vital as the artistic concept itself in cementing the gun barrel sequence as an enduring and effective signature device, perfectly framing Bond’s first steps into the cinematic universe.

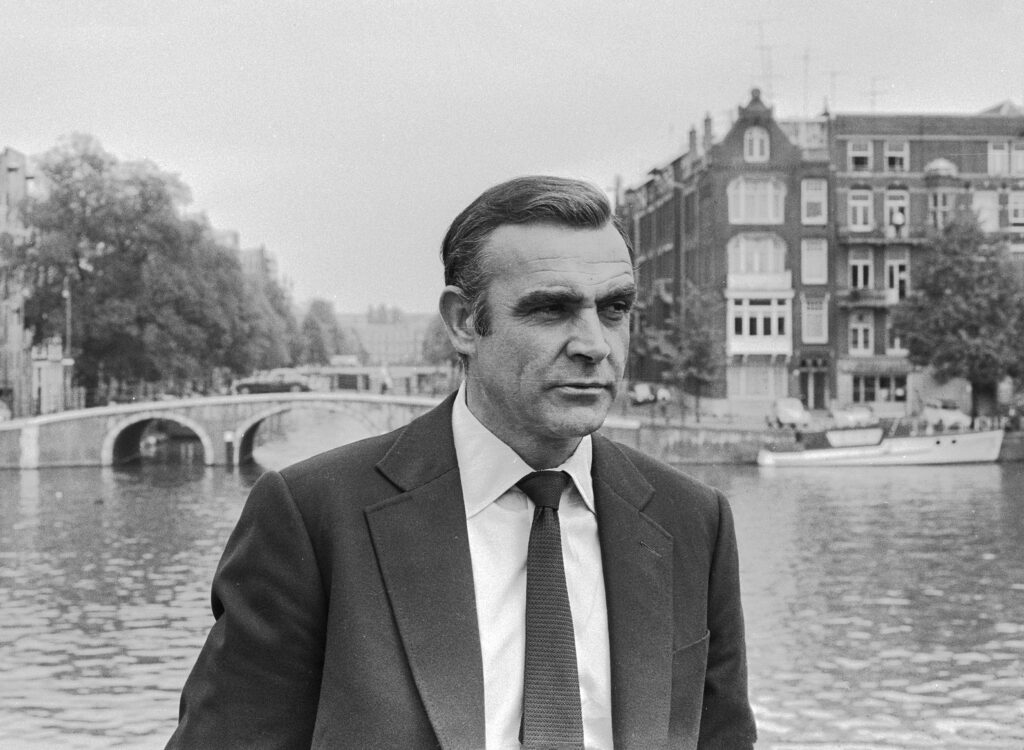

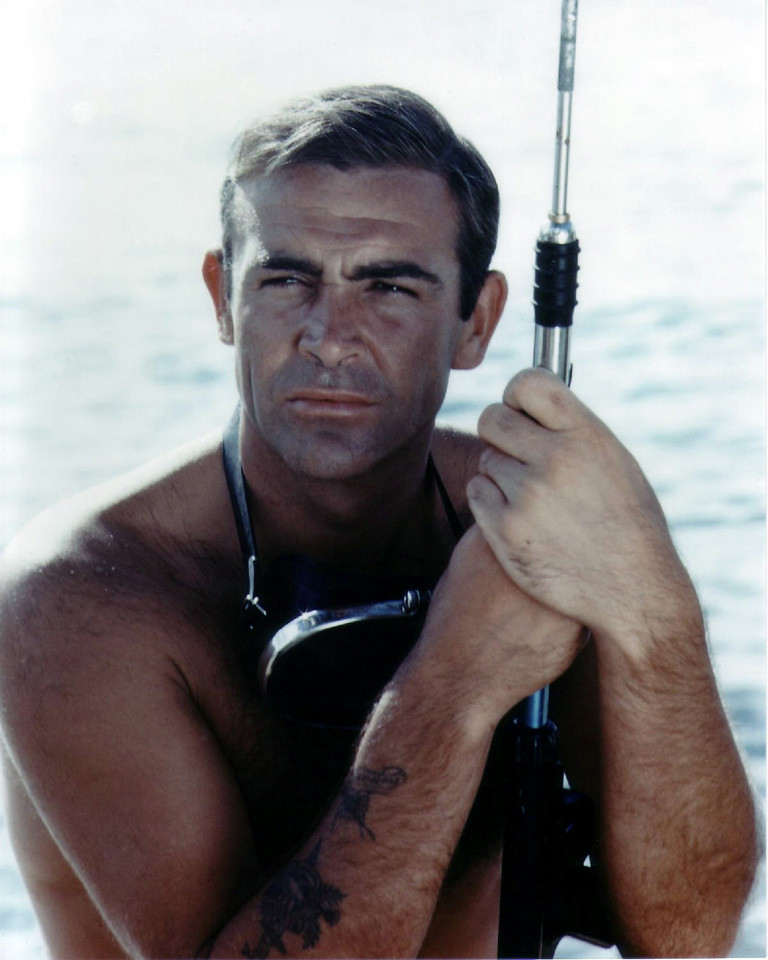

4. **Connery’s Panavision Pivot: The Thunderball Reshoot (1965-1967)**The cinematic landscape of James Bond evolved rapidly, and with it, the technical specifications of its signature opening. By the time *Thunderball* arrived in 1965, a significant change in the film’s production necessitated a complete overhaul of the gun barrel sequence. The aspect ratio of the Bond films shifted to a Panavision anamorphic format, a wider screen presentation that offered a more expansive visual experience. This change meant that the original gun barrel, filmed with Bob Simmons in the earlier, narrower aspect ratio, could no longer be used without compromising visual quality.

Consequently, the gun barrel sequence had to be reshot, and this time, the true star of the franchise, Sean Connery, stepped into the frame. This marked a significant moment: for the first time, the actor portraying James Bond himself would perform the iconic walk and shot that introduced his films. This decision not only brought an authentic touch to the opening but also allowed Connery to imprint his own physical presence onto this crucial introductory motif, further solidifying his portrayal of 007 from the very first moments of the film.

Connery’s performance in this reshot sequence brought distinct characteristics that set it apart from Simmons’s earlier rendition. The context describes Connery’s movements, noting that he “wobbles slightly while firing his gun as he adjusts his balance from an unstable position and he bends over to fire.” These subtle human elements – the slight wobble, the bend to stabilize himself – added a sense of grounded realism to Bond’s otherwise superhuman composure, hinting at the physicality required for his perilous profession. It showcased a slightly less stylized, more human action than the purely silhouetted stunt work before it.

Furthermore, this particular gun barrel sequence held another significant first: it was the initial instance where the white dot seamlessly transitioned into the film’s pre-credit sequence. Instead of simply fading out or disappearing, the white dot expanded, “opening up to reveal the entirety of the scene,” a sophisticated visual segue that enhanced the narrative flow. Though originally filmed in color for *Thunderball*, this same Connery sequence was later utilized for *You Only Live Twice*, where it was rendered in black and white, demonstrating its versatility and enduring power despite visual alterations. This version of the walk, with Connery at its center, became a foundational image for a generation of Bond fans.

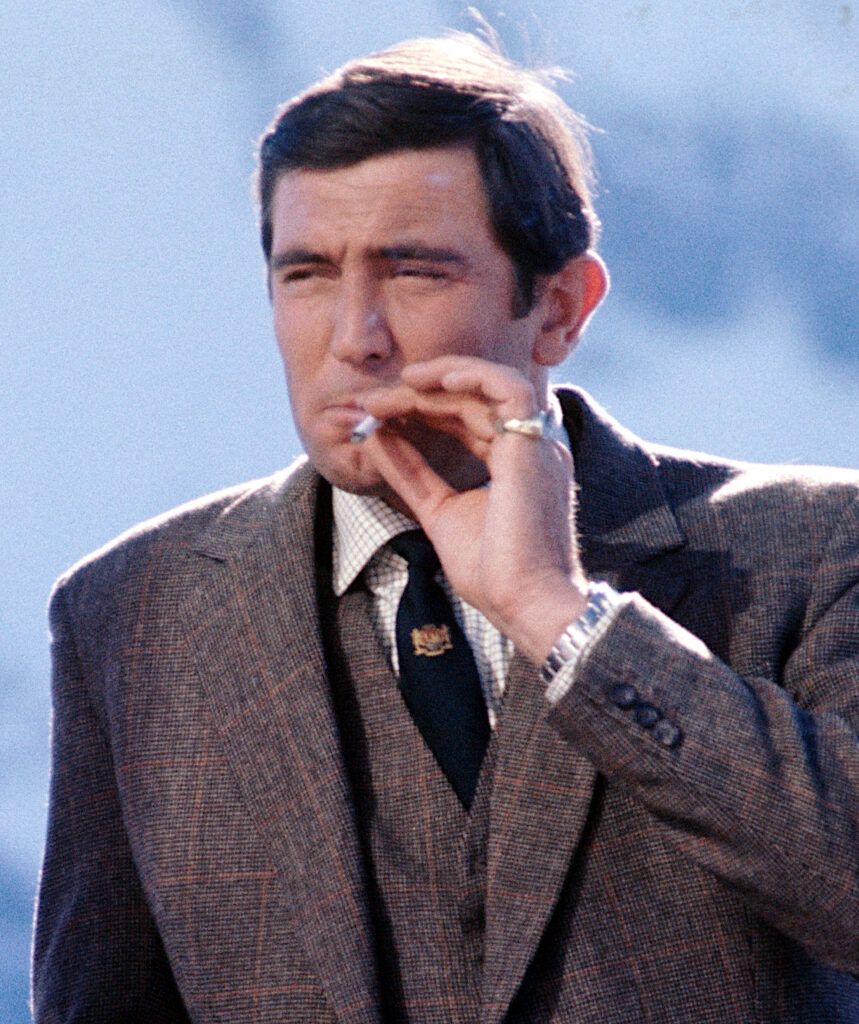

5. **Lazenby’s Distinctive Kneel: A New Interpretation (1969)**The Bond franchise saw a pivotal shift in 1969 with the introduction of a new actor, George Lazenby, taking on the mantle of 007 for *On Her Majesty’s Secret Service*. With a new leading man came the necessity for a fresh interpretation of the iconic gun barrel sequence, reflecting the distinct physicality and style that Lazenby brought to the role. This third iteration of the sequence was once again filmed in color, embracing the vibrancy of the era and providing a fresh visual take on the established tradition.

Lazenby’s gun barrel sequence introduced several unique elements that set it apart. The white dot, as seen in *Dr. No*, paused mid-screen, allowing the credit line “Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli Present” to appear, though notably spelling out “and” rather than using the ampersand. This subtle textual change acknowledged a continuity with the past while still hinting at new departures. The accompanying “James Bond Theme” continued to play, underscoring the enduring musical identity of the franchise even as its visual representation evolved.

The most striking difference in Lazenby’s performance of the walk and shot was his distinctive posture. The context explicitly states, “Lazenby is the only Bond who kneels down to fire.” This particular action distinguished his gun barrel from all preceding and subsequent versions. It implied a deliberate, almost ceremonial precision in his combat stance, a unique physical signature that immediately identified his Bond. The camera’s movement also contributed to a specific visual effect: “Bond is walking to position for around a second before turning and shooting as the camera tracks with him, resulting in a ‘treadmill’ effect,” giving the illusion of continuous motion within a confined space.

Another significant visual characteristic of Lazenby’s sequence was the vibrant, almost artistic use of light. The gun barrel itself was “awash with prismatic splashes of light,” adding a dynamic, almost psychedelic flair to the metallic interior. This visually rich detail added a layer of modern aesthetic to the classic opening. Uniquely, in this version, the descending blood wash was so complete and encompassing that it “completely erase[d] Bond’s image, leaving only the red circle.” This total obliteration of Bond’s figure by the blood lent a particularly stark and final feel to the sequence, emphasizing the deadly consequences of the confrontation and making Lazenby’s brief, but memorable, gun barrel truly stand out.

6. **The Resurfaced Walk: Connery’s Return in Diamonds Are Forever (1971)**When Sean Connery famously returned to the role of James Bond for *Diamonds Are Forever* in 1971, audiences might have expected a completely new gun barrel sequence to mark his triumphant, albeit temporary, comeback. However, the production made a pragmatic and perhaps nostalgic choice: they opted to reuse the gun barrel sequence that had originally been filmed for *Thunderball*. This decision connected his return to his earlier, highly successful tenure, offering a familiar opening despite the years that had passed since his last portrayal.

Despite the reuse of the underlying footage, the sequence was not presented in its original *Thunderball* form. Just as it had been altered for *You Only Live Twice*, the *Thunderball* sequence for *Diamonds Are Forever* was once again rendered in black and white. This choice imparted a sense of classicism, a nod to the monochromatic origins of the franchise. However, to distinguish it further, it was notably “given a bluish tint,” adding a subtle, cool aesthetic that imbued the familiar footage with a fresh, albeit muted, visual characteristic. This demonstrates how even a reused sequence could be recontextualized through color and tinting.

Further visual refinements were applied to this re-edition. Echoing the stylistic innovation seen in George Lazenby’s earlier sequence, the gun barrel in Connery’s *Diamonds Are Forever* opening was also “awash with prismatic splashes of light,” creating a dynamic play of color and reflection within the metallic confines. However, a key distinction was made in how these light effects interacted with the subsequent blood wash. Unlike Lazenby’s version where the light persisted within the blood, here, the “splashes of light are erased by the descending blood,” emphasizing the definitive and overwhelming nature of the fatal shot.

This specific iteration of the gun barrel sequence marked another historical point within the franchise. It was the last time the sequence would be rendered in black and white until the modern era of *Casino Royale* in 2006, highlighting its place as a bookend to a particular stylistic period. Furthermore, it holds the distinction of being “the last gun barrel sequence in which Bond wears a hat.” This detail, often overlooked, underscores the gradual evolution of Bond’s character design and overall aesthetic, moving away from the more formal, classic spy silhouette towards a more contemporary, unadorned look that would define later interpretations. It was a final, elegant farewell to an era of Bond style.

7. **Roger Moore’s Era Begins: A Fourth Sequence (1973-1974)**As the James Bond saga transitioned into a new era, so too did its iconic opening. With the charismatic Roger Moore stepping into the role of 007, a fresh gun barrel sequence was deemed essential, marking the fourth distinct iteration in the franchise’s history. This change wasn’t merely cosmetic; it coincided with a shift in cinematic aspect ratio, moving to a 1.85:1 matted format, which required a completely new shoot to ensure visual fidelity on the big screen.

This particular gun barrel sequence, shot specifically for Roger Moore, made its debut in *Live and Let Die*, the film that introduced audiences to his interpretation of Bond. It was then repurposed for his subsequent outing, *The Man with the Golden Gun*. Unlike some earlier sequences that saw extensive reuse or re-tinting across multiple films, this specific version of Moore’s walk was utilized for just these two productions, firmly establishing his initial physical presence in the role for a foundational period of his tenure.

While the core elements of the gun barrel remained – Bond’s purposeful walk, the sudden turn, and the decisive shot – each actor imbued the movements with their own subtle flair. Though the provided details for Moore’s specific bodily actions are less explicit than those for Simmons, Connery, or Lazenby, the very act of creating a new sequence signified the franchise’s commitment to adapting its signature device to reflect its current star, ensuring that the introduction felt fresh and aligned with the contemporary portrayal of the world’s most famous spy.

8. **The Consistent Visual Language: The Enduring White Dot**One of the most instantly recognizable, yet perhaps least consciously acknowledged, elements of the James Bond gun barrel sequence is the ubiquitous white dot. Far from being a mere aesthetic flourish, this small, pulsating circle serves as a vital visual cue, a narrative device that both initiates and frames the entire deadly ballet. It’s the viewer’s first tangible entry point into Bond’s world, a subtle yet effective mechanism that primes the audience for the espionage thrills ahead.

The sequence consistently begins with this white dot blinking across the screen, traversing from left to right with a deliberate, almost hypnotic rhythm. This journey isn’t just a simple line of movement; it guides the eye, creating a sense of anticipation before it culminates in a dramatic revelation. Upon reaching the right edge of the frame, the dot undergoes a transformation, majestically opening up to unveil the ominous, rifled interior of a gun barrel, a visual invitation into the heart of danger that is intrinsically Bond.

This consistent visual language, centered around the white dot, is a testament to Maurice Binder’s initial genius. It offers a sense of continuity across different actors and eras, anchoring the diverse interpretations of Bond within a unified cinematic framework. The dot’s journey, its expansion into the barrel, and its eventual role in the sequence’s conclusion (whether fading out, shrinking, or expanding into the pre-credit scene) makes it a silent, yet powerful, co-star in every Bond opening, a small detail with outsized narrative weight, setting the stage for every subsequent moment of suspense and action.

Read more about: Beyond Boot Camp: 14 Essential Military Hacks That Could Be Your Lifeline in a Crisis

9. **The Iconic Soundscape: Monty Norman’s Enduring Theme**The James Bond gun barrel sequence is not solely a visual spectacle; its power is profoundly amplified by its accompanying score, particularly the legendary “James Bond Theme” by Monty Norman. This distinctive musical motif is as synonymous with 007 as the Aston Martin or the shaken-not-stirred martini, acting as an auditory shorthand that instantly evokes the world of espionage and adventure. The theme’s blend of brass, surf guitar, and jazzy undertones perfectly encapsulates Bond’s coolness, danger, and sophistication.

While the “James Bond Theme” has become the default soundscape for almost every iteration of the gun barrel, the very first sequence in *Dr. No* featured a more experimental, perhaps even eerie, auditory prelude. Prior to the gunshot, audiences were met with a series of “electronic noises and then numerous notes that sound like they are being plinked from a wind-up jack in the box.” This early, almost toy-like sound was abruptly cut short by the visceral gunshot, creating a stark contrast that heightened the sudden violence of the moment. This unique sound design, though later replaced by the full theme, highlights the early exploration of how sound could amplify the sequence’s psychological impact.

The eventual integration of the full “James Bond Theme” into the gun barrel sequence was a stroke of genius, transforming it from a mere visual intro into a multisensory experience. The theme’s iconic opening notes, often played loudly and with immediate impact, serve to galvanize the audience, signaling the commencement of another thrilling adventure. This careful marriage of sight and sound ensures that the gun barrel doesn’t just introduce Bond; it *announces* him, creating an unbreakable bond between the visual act of turning and firing and the unforgettable musical identity of the franchise.

10. **The Psychological Impact: The Unseen Assailant’s Gaze**The profound impact of the gun barrel sequence stems not just from its visual flair or memorable music, but from a deeply ingrained psychological tactic: placing the audience directly in the crosshairs. Described as being “shot from the point of view of a presumed assassin,” this narrative choice is a masterclass in immersive storytelling, immediately thrusting the viewer into a position of vulnerability and confrontation. We are, for a fleeting moment, the target, an unseen antagonist about to face the legendary spy.

This unique perspective creates an instant connection with the core tenets of the spy genre. As the British media historian James Chapman astutely observes, the sequence “foregrounds the motif of looking, which is central to the spy genre.” It’s about surveillance, observation, and the chilling realization of being watched. By making the audience the ‘watcher’ who is then ‘seen’ and confronted by Bond, the sequence cleverly reverses expectations, underscoring the lethal capabilities of 007 and his unparalleled awareness of his surroundings.

Furthermore, Chapman draws a compelling parallel between this sequence and the pioneering 1903 film *The Great Train Robbery*, where a gun is famously fired directly at the audience. This historical echo grounds the Bond gun barrel in a rich cinematic tradition of breaking the fourth wall and creating a visceral, shared experience. It’s a moment of direct engagement that transcends mere introduction, establishing Bond’s deadly precision and the ever-present danger of his world by making the viewer an unwitting participant in a life-or-death scenario, a brilliant piece of psychological priming.

11. **The Cinematic Transition: Evolving Segues into the Story**Beyond the dramatic walk and shot, a crucial, yet often underappreciated, aspect of the gun barrel sequence is its transition into the film’s opening scene or title sequence. This cinematic segue is not a static element; it has undergone its own subtle evolution, acting as a crucial bridge that seamlessly carries the audience from the iconic introduction into the narrative proper. The methods employed for this transition are varied, each designed to serve the pacing and style of the particular film.

Initially, the white dot that concludes the gun barrel sequence might simply shrink and vanish, allowing for a clean cut to the subsequent credits or pre-title action. Alternatively, the gun barrel itself could move from side-to-side across the screen before dissolving into this familiar white dot, or sometimes even fade directly to black. These early transitions, though effective, laid the groundwork for more sophisticated narrative integration, demonstrating the sequence’s adaptability to evolving cinematic techniques and storytelling demands.

A significant leap in this evolution occurred with Sean Connery’s *Thunderball* sequence, which marked the first instance where the white dot transcended its simple role of fading out. In this version, the dot dramatically “segues to the film’s pre-credit sequence, opening up to reveal the entirety of the scene.” This innovative approach transformed the gun barrel from a discrete opening motif into an organic, expanding portal directly into the film’s narrative, enhancing immersion and narrative flow. This evolution in transitional techniques underscores how the gun barrel, despite its fundamental consistency, continued to innovate, refining its role as a powerful, dynamic gateway into the exhilarating world of James Bond.

12. **Enduring Legacy: A Symbol of Global Espionage**The James Bond gun barrel sequence has transcended its origins as a mere opening credit to become an enduring symbol, not just of the 007 franchise, but of global popular culture itself. For over six decades, this brief, powerful flourish has remained an instantly recognizable hallmark, a testament to brilliant design and psychological priming that continues to captivate and thrill audiences worldwide. It’s more than just an intro; it’s a carefully crafted piece of film history that tells a story in mere seconds, establishing mood, character, and the ever-present danger that defines Bond’s world.

Its continued prominence is evident in its heavy feature in marketing materials for films and spin-offs, cementing its status as an iconic visual and auditory signature. The sequence has become so ingrained in the collective consciousness that it immediately conjures images of suave spies, sophisticated gadgets, and high-stakes adventure, effectively serving as an emblem for the entire espionage genre. This widespread recognition speaks volumes about its power to encapsulate complex themes and emotions within a concise, impactful moment.

Read more about: Unpacking the Legacy: 12 Pivotal Chapters in the Illustrious Life of George Washington

Ultimately, the gun barrel sequence has solidified its place as a cornerstone of cinematic identity. It’s a testament to how simple techniques, born from quick thinking and technical ingenuity, can evolve into legendary artistic expressions. From Maurice Binder’s hurried sketch to the nuanced interpretations of various actors, this opening flourish continues to prepare audiences for the thrills to come, a timeless prelude that remains as vital to James Bond’s allure as his wit, his women, and his license to kill. It’s a signature device that has not only endured but thrived, securing its legacy as one of cinema’s most unforgettable introductions.