In our increasingly digital lives, the ability to seamlessly extend and manage our screen real estate is not just a convenience—it’s a productivity superpower. Whether you’re looking to share a presentation, enjoy media on a larger display, or harness the full potential of your terminal environment, understanding the tools at your disposal can dramatically transform your computing experience. From wirelessly projecting your Windows desktop to mastering the intricacies of a venerable terminal multiplexer, the world of ‘screen’ offers a fascinating array of functionalities designed to make your digital interactions more fluid and efficient.

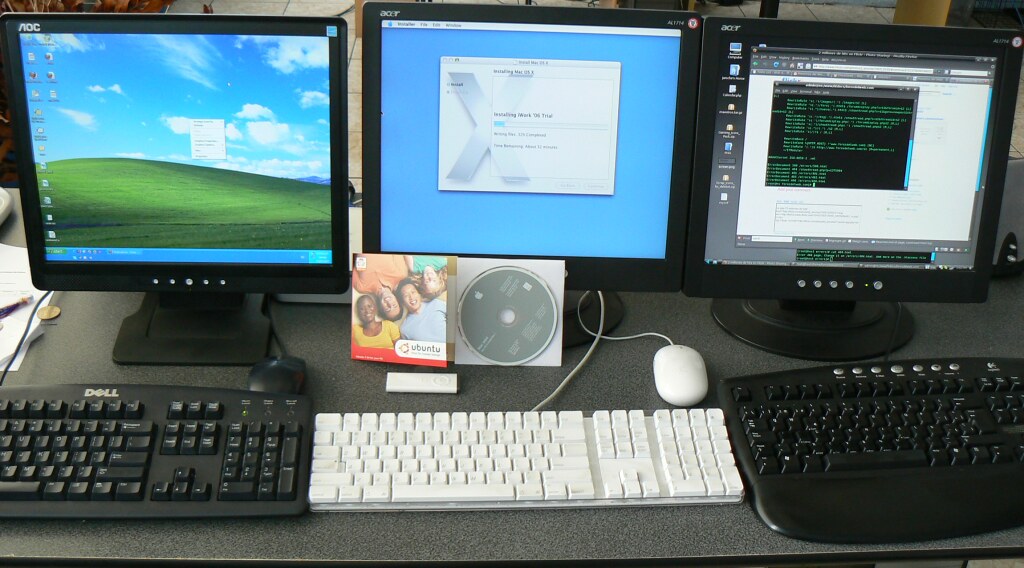

Today, we’re diving deep into two distinct yet equally vital aspects of screen management. First, we’ll unravel the straightforward methods Windows provides for mirroring your display to external monitors, TVs, or projectors, enabling you to effortlessly share your content. Then, we’ll embark on an exciting journey into the robust universe of GNU Screen, a powerful utility that allows you to manage multiple terminal sessions within a single window, ensuring your command-line work remains persistent and organized, no matter where you are or what disruptions might occur.

Prepare to unlock new levels of control over your digital workspace as we explore these essential techniques. Get ready to discover surprising capabilities and practical tips that will enhance your daily workflow, making you wonder how you ever managed without them. Let’s delve into the fascinating mechanics of screen extension and terminal management that are far more powerful than you might initially imagine.

1. **Windows Screen Mirroring: The Seamless HDMI Connection**

One of the most universally accessible ways to expand your visual workspace or share your computer’s display with a larger audience is through the trusty HDMI cable. This simple yet powerful solution allows for the direct transmission of high-definition, uncompressed audio and video output from your computer to an external display. It’s a plug-and-play marvel that brings your content to life on a TV, monitor, or projector with remarkable clarity and ease.

Connecting your devices with an HDMI cable is wonderfully straightforward. First, you’ll need to ‘Get an HDMI cable.’ These are readily available online or at any electronics store. Once you have your cable, the process is as simple as plugging one end into your computer’s HDMI port—typically found on the side of a laptop or the back of a desktop—and the other end into an HDMI port on your chosen display, be it a TV, monitor, or projector. The beauty of HDMI cables is that “Both ends of the HDMI cable look the same,” so there’s no wrong way to plug them in, simplifying the connection process.

Of course, not all devices are created equal, and you might occasionally encounter a situation where one of your devices lacks a standard HDMI port. Fear not! The modern tech landscape offers solutions for almost every scenario. In such cases, you can easily “purchase an adapter, or use a different cable such as Mini DisplayPort to HDMI” to bridge the connection. Once everything is physically linked, the final step is to “Switch your TV or projector to the HDMI input.” If your display has more than one HDMI port, you’ll just need to select the correct one, and like magic, “your computer’s screen will be automatically mirrored on your TV or projector.” It’s truly that simple to achieve a powerful visual extension!

2. **Windows Screen Mirroring: Unleashing Wireless Freedom with Miracast**

While physical cables offer a reliable connection, the allure of a wireless solution for screen mirroring is undeniable. Enter Miracast, Windows’ built-in feature designed to effortlessly ‘mirror your screen on a wireless projector, monitor or TV.’ This ingenious technology liberates you from the confines of cables, allowing for greater flexibility in your setup and presentations. Imagine sharing your work or entertainment across the room without a single wire tethering your device!

To embark on your wireless mirroring adventure with Miracast, a few foundational steps ensure a smooth experience. Crucially, “Your receiver display must be connected to the same wireless network as your computer to use Miracast’s screen mirroring feature.” This shared network connection is the backbone of the wireless link, so always double-check your Wi-Fi status on both devices. While the precise “Setting up your projector, monitor or TV will vary from device to device,” referring to your display’s manual will provide specific guidance for getting it ready to receive the Miracast signal.

Once your receiver display is prepped and on the same network, initiating the connection from your Windows computer is a breeze. Begin by opening your “Start menu” (the Windows icon in the lower-left corner) and clicking the “gear icon” to access Settings. From there, navigate to “Devices,” then “Bluetooth & other devices” on the left menu. Next, click “+ Add Bluetooth or other device” and select “Wireless display or dock” from the options. This action triggers a scan of your network, populating a list of available display devices. Simply “Click your display’s name on the ‘Add a device’ menu” to connect. You might be prompted to confirm the connection on your receiver display, but once accepted, “This will connect to the selected device, and mirror your computer’s screen to your projector, monitor or TV.” With a final click of the “Done” button, you’re free to enjoy your wirelessly mirrored screen, a true testament to modern connectivity!

Product on Amazon: Wireless HDMI Display Dongle Adapter, Plug & Play 4K HDMI Wireless Screen Mirroring Adapter for TV, 5G Streaming Video from Phone Tablet Laptop to TV/Monitor/Projector, Support AirPlay DLNA Miracast

Brand: MpioLife

Binding: Product Group: Personal Computer

Price: 69.99 USD

Rating: 4.4 Total reviews: 22

Connectivity Technology: HDMI, Wi-Fi, Wireless

Connector Type: HDMI

Resolution: 4k

Controller Type: Button Control

Color: Black

Item Weight: 23 Grams

Product Dimensions: 2.36″L x 2.36″W x 0.39″H

Shopping on Amazon >>

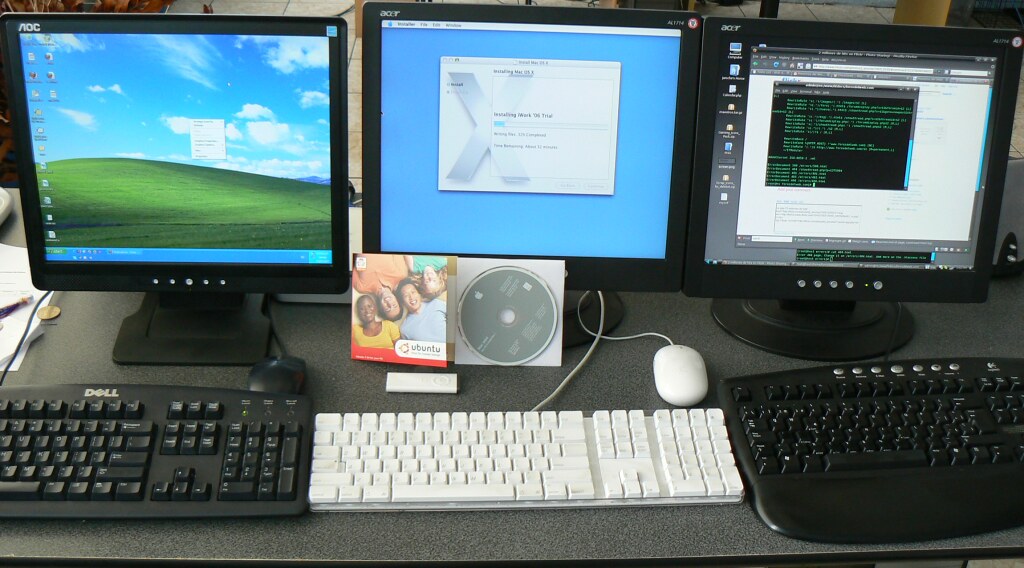

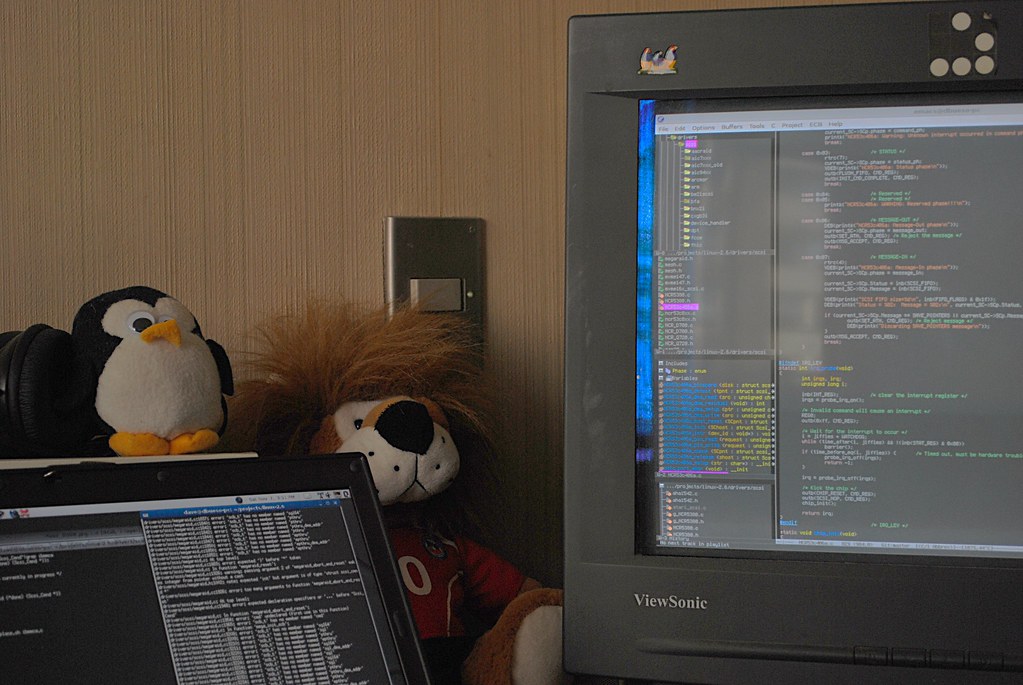

3. **GNU Screen: The Ultimate Terminal Multiplexer (Overview)**

Stepping away from graphical screen mirroring, we now delve into a different, yet equally revolutionary, concept of ‘screen’ – the command-line utility known as GNU Screen. For anyone who spends significant time in a terminal, Screen is nothing short of a revelation, a ‘full-screen window manager that multiplexes a physical terminal between several processes, typically interactive shells.’ It’s like having an entire suite of virtual terminals at your fingertips, all residing within a single physical terminal window. This foundational capability means you can run multiple programs, shells, or commands concurrently and interact with them independently.

At its core, GNU Screen provides the robust functions of a ‘DEC VT100 terminal,’ while also incorporating ‘several control functions from the ISO 6429 (ECMA 48, ANSI X3.64) and ISO 2022 standards,’ offering advanced features such as insert/delete line and support for multiple character sets. But its true power extends far beyond simple emulation. Imagine needing to scroll back through extensive output or copy text between different active terminal sessions; Screen makes this effortless with ‘a scrollback history buffer for each virtual terminal and a copy-and-paste mechanism that allows the user to move text regions between windows.’ This alone can be a monumental time-saver for developers, system administrators, and anyone dealing with complex command-line tasks.

One of Screen’s most compelling features is its ability to maintain running programs even when you’re not actively viewing them. “Programs continue to run when their window is currently not visible and even when the whole screen session is detached from the user’s terminal.” This persistent nature is a game-changer; you can start a long-running process, detach your Screen session, log out, and even shut down your client machine, only to reattach later from anywhere and find your process still diligently working. When Screen is initially launched, it “creates a single window with a shell in it (or the specified command) and then gets out of your way so that you can use the program as you normally would.” It’s designed to be unobtrusive, allowing you to focus on your work while it quietly manages the underlying complexities of your terminal environment.

4. **Getting Started with GNU Screen: Essential Preparations**

Before you fully unleash the power of GNU Screen, a brief moment of preparation can ensure an optimal experience. Just as with any other terminal-based application utilizing `termcap`/`terminfo`, it’s crucial to ‘make sure you have correctly selected your terminal type.’ This foundational step ensures that Screen can accurately interact with and display information on your specific terminal emulator. Methods like using `tset`, `qterm`, or simply setting `term=mytermtype` can help you achieve this, providing a stable canvas for your multiplexed sessions.

For those eager to dive right in without extensive reading, GNU Screen offers a friendly entry point. Remember this one indispensable command: `C-a ?`. Typing these two characters will instantly “display a list of the available screen commands and their bindings.” It’s your built-in cheat sheet, a handy reference that will save you countless trips to the manual as you learn the ropes. Each keystroke is meticulously documented, making the learning curve surprisingly manageable for such a feature-rich tool.

Considering the type of terminal you’re using can also significantly impact Screen’s performance and display accuracy. The context notes that most modern terminals benefit from ‘“magic” margins (automatic margins plus usable last column)’—a VT100-style behavior that is ‘perfectly suited for screen.’ However, if you find yourself with a ‘“true” auto-margin terminal’ that doesn’t allow the last position on the screen to be updated without scrolling, Screen will still function, but updates to characters in the last column might be delayed. In such rare cases, using a `termcap` version with automatic margins turned off or a terminal with `insert-character` capability can help ‘shorten’ this delay, ensuring a smoother visual experience.

5. **Mastering GNU Screen’s Command Character and Fundamental Key Bindings**

At the heart of interacting with GNU Screen lies its unique command structure, centered around a special ‘command character.’ By default, this pivotal character is `control-a` (abbreviated `C-a`). Almost every instruction you give to Screen, from switching windows to managing sessions, begins with this essential prefix, followed by one additional keystroke. It’s the secret handshake that distinguishes your commands for Screen from the input you’re sending to the program running within your current window.

While `C-a` serves as the default, flexibility is one of Screen’s hallmarks. The “command character… and all the key bindings… can be fully customized to be anything you like.” This means you’re not locked into the default; you can tailor Screen to perfectly match your personal preferences and avoid conflicts with other applications you might be using. Whether you prefer `C-b` or another combination, Screen allows you to define your escape sequence, making the tool truly your own. It’s worth noting that while this manual uses `C-a` for readability, Screen’s internal representation often uses caret notation (e.g., `^A`).

Screen comes with a rich set of ‘Default Key Bindings’ that cover a vast array of functionalities. For convenience, many commands bound to lowercase letters are also accessible via their Control character counterparts (e.g., `C-a c` and `C-a C-c` both create a new window). From the fundamental `C-a ?` (which, as we just learned, displays all key bindings) to `C-a ‘` for selecting a window by identifier, or `C-a “` to present a list of all windows for selection, these bindings are your direct line of communication with Screen’s powerful window manager. Learning these shortcuts will significantly accelerate your workflow, transforming complex multi-terminal tasks into fluid, single-keystroke operations.

6. **Creating and Managing Multiple Windows in GNU Screen: A Multitasking Powerhouse**

One of the most compelling reasons to embrace GNU Screen is its exceptional ability to manage multiple, independent terminal windows within a single physical display. This feature transforms your terminal from a solitary workspace into a dynamic multitasking environment, allowing you to juggle development, system monitoring, and administrative tasks with unprecedented ease. The power to create and orchestrate these windows is fundamental to Screen’s design, enabling a truly parallel workflow where each task has its dedicated space.

The standard and most direct way to generate a new window is beautifully simple: type `C-a c`. This command “creates a new window running a shell and switches to that window immediately,” providing you with a fresh prompt for a new task. The beauty is that this happens “regardless of the state of the process running in the current window,” ensuring your ongoing operations remain undisturbed. Beyond the default shell, you can also launch a new window with a specific command, such as `screen emacs prog.c` from an existing Screen shell. This tells the window manager to open a new window and start the `emacs` editor with `prog.c` loaded, seamlessly integrating applications into your Screen session.

Once you have multiple windows, efficient navigation is paramount. Screen offers several intuitive ways to switch between them. For a quick hop to the next or previous window, you can use `C-a n` (next) or `C-a p` (previous). If you know the window number, `C-a 0` through `C-a 9` provides instant access. For a more visual overview, `C-a “` will “Present a list of all windows for selection,” allowing you to pick your destination from a clear menu. Keeping track of your tasks is also made easier by assigning meaningful names: `C-a A` lets you “Allow the user to enter a title for the current window,” replacing generic numbers with descriptive labels that make identification effortless.

7. **Detaching and Reattaching GNU Screen Sessions: The Art of Persistence**、

Perhaps the single most celebrated feature of GNU Screen, and a primary reason many users adopt it, is its unparalleled ability to detach and reattach sessions. Imagine you’re running a critical compilation, a long data transfer, or a complex script on a remote server. What happens if your network connection drops, or you need to switch computers? Without Screen, your process would terminate. With Screen, you can simply “detach screen from this terminal” (using `C-a d` or `C-a C-d`), preserving your entire terminal environment—all your running programs and open windows—exactly as you left it.

Once detached, your Screen session continues to run in the background on the server, completely independent of your client terminal. When you’re ready to resume your work, from the same machine or a different one, you can “Resume a detached screen session” using the `screen -r` command. This magic allows you to pick up exactly where you left off, as if you never disconnected. If you have multiple detached sessions, you might need to specify a session name or identifier to distinguish them, but the core functionality remains: seamless persistence.

Screen offers even more powerful options for managing detachment and reattachment. For instance, the combination `screen -d -r` allows you to “Reattach a session and if necessary detach it first,” ensuring a clean reattachment even if the session was previously “attached” elsewhere. The `-R` option takes this a step further, resuming “only when it’s unambiguous which one to attach,” and if no detached session exists, it will “start a new session using the specified options.” For the ultimate “Attach here and now” experience, the author’s favorite `screen -D -R` command “will create it and notify the user” if no session is running, or “detach and logout remotely first” if one is already attached. This ensures you always get into a working session, reflecting the robust, fault-tolerant nature of GNU Screen.

8. **Logging and Scrollback in GNU Screen: Capturing and Reviewing Your Terminal History**

One of the often-unsung heroes of terminal productivity within GNU Screen is its robust handling of output logging and scrollback history. Imagine a scenario where you’re monitoring a complex log file or debugging a script that produces verbose output. Screen ensures you never lose a single line, even if it scrolls off the visible screen, thanks to its dedicated history buffers. This capability transforms fleeting terminal output into a persistent record you can consult at your leisure.

Each virtual terminal within Screen is equipped with its own scrollback history buffer, acting as a digital archive for everything that has appeared in that window. To engage with this powerful feature, simply enter ‘copy/scrollback mode’ using the `C-a [` command. Once in this mode, you can navigate through past output, review critical information, and even select text regions for copying. This text can then be moved between windows using Screen’s integrated copy-and-paste mechanism, making it incredibly easy to extract information from one session and use it in another.

Beyond interactive scrollback, Screen offers automatic output logging. You can toggle logging for the current window with `C-a H`, which by default writes the output to a file named ‘screenlog.n’ (where ‘n’ is the window number). For a more persistent setup, the `deflog state` command allows you to select the default logging behavior for all new windows, and the `-L` command-line option can turn on automatic output logging from the start. Furthermore, you can control the size of these history buffers with the `-h num` option at invocation or through the `defscrollback num` command, ensuring you have enough historical depth for even the most demanding tasks. For those who like a tidy history, the `compacthist` command offers options for selecting compaction of trailing empty lines, keeping your scrollback clean and efficient.

9. **Customizing Your GNU Screen Environment: The Power of .screenrc**

Just like a well-appointed workshop reflects its artisan, a well-configured GNU Screen environment reflects its user. The `.screenrc` file is your personal blueprint for Screen, a powerful configuration file that allows you to tailor almost every aspect of its behavior to your specific preferences and workflow. This file, typically residing in your home directory, contains commands that Screen executes at startup, setting the stage for every session you embark on.

Within `.screenrc`, you can define a vast array of settings, from binding custom commands to specific keys to automatically establishing one or more windows at the beginning of your Screen session. Each command occupies its own line, with arguments separated by tabs or spaces, and can be enclosed in single or double quotes for clarity. Should you wish to annotate your configuration, a `#` character turns the rest of the line into a comment, a useful practice for documenting your customizations. You can even embed references to environment variables using shell-like syntax, such as `$VAR` or `${VAR}`, though it’s important to remember to protect the `$` character with a backslash if literal dollar signs are intended.

For those who prefer not to use the default `$HOME/.screenrc` location, the command-line option `-c file` allows you to specify an alternative configuration file. This flexibility is particularly useful for managing different Screen setups for various projects or environments. Screen also supports nested configuration, meaning you can use the `source file` command within your `.screenrc` to read and execute commands from other files, enabling modular and organized configurations. It’s a testament to Screen’s design that it offers such deep customization, allowing users to craft an environment that feels intimately their own, maximizing comfort and efficiency.

10. **Dynamic Customization with GNU Screen’s Colon Command: On-the-Fly Adjustments**

While the `.screenrc` file provides a powerful foundation for your GNU Screen environment, there are times when you need to make quick, temporary, or session-specific adjustments without editing a file and restarting your session. This is where Screen’s versatile ‘colon command’ comes into play. Accessed by typing `C-a :`, this interactive command line allows you to modify settings and key bindings in a live session, providing unparalleled flexibility for on-the-fly adjustments.

Think of the colon command as Screen’s interactive control panel, much like the `ex` command mode in `vi` or `vim`. Here, you can type nearly any command that you would typically put in your `.screenrc` file. Whether you need to quickly change a key binding, create a specific window with a custom command, or modify a default setting, `C-a :` empowers you to do so dynamically. This interactive approach is invaluable for experimenting with new configurations or responding to immediate workflow needs without interruption.

It’s worth noting a subtle but important detail for long-time Screen users: as of version 3.3, the `set` keyword for changing settings no longer exists. Instead, default settings are modified using commands that begin with `def`, such as `defflow` or `defscrollback`. This change streamlines the command language, making it more consistent. The colon command truly solidifies Screen’s reputation as a tool that not only provides robust terminal multiplexing but also puts deep control directly into the hands of the user, precisely when and where it’s needed.

11. **Multiuser Sessions in GNU Screen: Collaborative Terminal Access and Security**

In an era of increasing collaboration and distributed teams, GNU Screen steps up with a powerful, yet often overlooked, feature: multiuser sessions. This functionality transforms a single Screen session into a shared workspace, allowing multiple users to connect to the same session simultaneously, viewing and interacting with the same terminal windows. It’s like having a shared digital desk for your command-line tasks, perfect for pair programming, remote assistance, or interactive demonstrations.

Enabling multiuser mode is the first step, and from there, Screen provides a suite of commands to manage who can access your session and what permissions they have. Commands like `acladd usernames` allow you to grant access to specific users, while `aclchg usernames permbits list` provides granular control over their permissions within the session. Should a user’s access need to be revoked, `acldel username` can easily remove them. For more complex setups, `aclgrp usrname [ groupname ]` enables users to inherit permissions from a group leader, and `aclumask [ users ]+/- bits …` can predefine access rights for new windows.

Security is paramount in shared environments, and Screen addresses this by offering password protection for sessions. By default, Screen allows attachment without a password, but the `-P` command-line option or the `auth on` command can enable authentication. This ensures that only authorized individuals with the correct password can connect to your multiuser session, safeguarding your shared terminal environment. For connecting to another user’s session in multiuser mode, the syntax `screen -r sessionowner /[ pid.sessionname ]` is used, often requiring `setuid-root` permissions. This entire system underscores Screen’s versatility, extending its utility from individual productivity to powerful collaborative tool.

12. **Advanced Session Management with GNU Screen’s Command-Line Options: Beyond the Basics**Beyond simply detaching and reattaching, GNU Screen offers a wealth of command-line options that elevate session management to an art form, allowing for intricate control over your persistent terminal environments. These advanced options empower users to organize, identify, and even interact with running Screen sessions from outside the session itself, providing a sophisticated toolkit for the power user.

Beyond simply detaching and reattaching, GNU Screen offers a wealth of command-line options that elevate session management to an art form, allowing for intricate control over your persistent terminal environments. These advanced options empower users to organize, identify, and even interact with running Screen sessions from outside the session itself, providing a sophisticated toolkit for the power user.

One invaluable option is `-S sessionname`, which allows you to assign a meaningful name to a new session instead of the default `tty.host` suffix. This named identifier then becomes crucial for commands like `screen -list` (or `-ls`), which prints a comprehensive list of all your active, detached, or even ‘dead’ sessions. The output of `-ls` provides vital status information, marking sessions as ‘detached,’ ‘attached,’ or ‘multi’ for multiuser mode. It also flags ‘unreachable’ sessions (those on a different host or truly ‘dead’) and explicitly identifies ‘dead’ sessions that should be thoroughly checked and potentially removed using the `-wipe` option.

Another incredibly potent tool is `screen -X`. This command allows you to send specified commands to a running Screen session from an external terminal. Imagine needing to open a new window, rename an existing one, or even send a keypress to a program within a detached session—all possible with `-X`. You can target a specific session using the `-S` option in conjunction with `-X`, or refine the search with `-d` or `-r` to target only detached or attached sessions. However, it’s a critical security note that this command will not work if the target session is password protected. These options collectively transform Screen from a mere terminal wrapper into a robust session manager, allowing for unparalleled control and automation of your command-line workflow.

13. **Fine-Tuning Display and Flow Control in GNU Screen: Optimizing Visuals and Interaction**

Optimizing the visual presentation and interaction within your GNU Screen sessions goes beyond just managing windows; it involves fine-tuning display characteristics and flow control mechanisms to ensure a smooth and efficient user experience. Screen offers a suite of commands and options to adapt to various terminal types and user preferences, ensuring your command-line environment is as responsive and clear as possible.

For instance, the `-A` option is designed to ‘Adapt the sizes of all windows to the size of the display’ when attaching to resizable terminals, preventing Screen from trying to restore outdated window dimensions. Similarly, the `-O` option helps ‘Select a more optimal output mode’ for certain terminal types, improving performance and visual fidelity. These subtle adjustments can make a significant difference in how text and graphical elements are rendered, ensuring your terminal adapts gracefully to different screen sizes and terminal emulators.

Flow control, which manages the rate at which data is sent between the terminal and the application, is another area of meticulous control. You can set flow control to ‘on,’ ‘off,’ or ‘automatic switching mode’ using the `-f`, `-fn`, or `-fa` command-line options, respectively, or dynamically with `C-a f` (which cycles through these states). This can be crucial for preventing fast-scrolling output from overwhelming slower terminals. Additionally, Screen allows you to manage line wrapping: `C-a r` toggles the current window’s line-wrap setting, effectively turning automatic margins on or off. Other options like `defautonuke state` enable or disable clearing the screen to discard unwritten output, and `defobuflimit limit` lets you control the output buffer size, all contributing to a finely tuned, personalized terminal experience that handles visual output and interaction exactly as you prefer.

14. **Navigating Regions and Layouts with GNU Screen: Advanced Window Organization**

For the truly advanced terminal user, GNU Screen offers an ingenious system of ‘regions’ and ‘layouts’ that allow you to subdivide your physical terminal screen into multiple, independently managed viewing areas. This capability moves beyond simply switching between full-screen windows to displaying several windows concurrently, significantly boosting productivity when monitoring multiple processes or comparing outputs side-by-side.

The magic begins with splitting your terminal. You can effortlessly divide your current region horizontally into two new ones using `C-a S`, creating distinct upper and lower panes. If a vertical division is more appropriate for your workflow, `C-a |` (that’s `C-a` followed by the pipe symbol) will split the current region vertically. Once you have multiple regions, navigating between them is intuitive: `C-a Tab` switches the input focus to the next region, allowing you to interact with the shell or program in that specific pane while others remain visible.

Managing these regions is also straightforward. If you decide you no longer need a particular split, `C-a X` will kill the current region, merging it with its neighbor. For a complete reset, `C-a Q` will delete all regions except the current one, restoring your terminal to a single, undivided display. The `C-a F` command is also handy, as it resizes the window to the current region size, ensuring optimal use of the available space. This sophisticated layout management transforms your terminal into a dynamic, multi-pane workspace, empowering you to orchestrate complex tasks with unprecedented visual organization and efficiency. It’s a testament to Screen’s enduring power that it provides such granular control over not just what you see, but how you see it.

From the straightforward simplicity of Windows screen mirroring to the profound depths of GNU Screen’s terminal multiplexing, we’ve journeyed through a landscape of tools designed to revolutionize your digital interaction. We’ve uncovered how a simple HDMI cable can bring your content to life on a larger display, how Miracast liberates you from physical connections, and how GNU Screen transforms the humble terminal into a persistent, multi-windowed powerhouse. Whether you’re managing complex server processes, collaborating with colleagues, or simply craving a more organized command-line workflow, the capabilities explored here offer pathways to unparalleled productivity. Embrace these tools, customize them to your heart’s content, and witness firsthand how mastering ‘screen’ can make your digital life not just easier, but genuinely more efficient and enjoyable. The power to orchestrate your digital workspace truly rests at your fingertips.