For many Americans approaching or beyond their 40th birthday, the word “colonoscopy” might conjure feelings of apprehension, discomfort, or even dread. It’s a natural human response to a medical procedure that involves a significant degree of preparation and an examination that can feel inherently invasive. However, it is crucial to reframe this perception, as a colonoscopy is not merely a diagnostic tool but a powerful, proactive measure in safeguarding one’s long-term health, particularly against colorectal cancer. It’s a procedure that, quite literally, saves lives by preventing disease before it even fully takes hold or by catching it at its most treatable stages.

Far from being a procedure to be feared, modern colonoscopy has evolved into a routine, safe, and remarkably effective examination. Advances in medical technology and patient care have significantly minimized discomfort and streamlined the process, making it an accessible and vital part of preventive healthcare. For individuals over 40, understanding the immense benefits and straightforward nature of this examination is paramount, as colorectal cancer remains a significant health concern, yet one that is largely preventable and highly curable when detected early.

This in-depth guide aims to demystify the colonoscopy, shedding light on every aspect from its fundamental purpose to what one can expect before, during, and after the examination. Our goal is to empower you with clear, evidence-based information, directly addressing common anxieties and replacing them with knowledge and confidence. By understanding the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of a colonoscopy, you can make informed decisions that prioritize your health and well-being, transforming apprehension into proactive health management.

1. **What Exactly is a Colonoscopy?**At its core, a colonoscopy (koe-lun-OS-kuh-pee) is an exam used to look for changes — such as swollen, irritated tissues, polyps or cancer — in the large intestine (colon) and rectum. It’s a comprehensive examination designed to provide your doctor with a direct and thorough view of these crucial parts of your digestive system, enabling the early identification of potential issues that might otherwise go unnoticed until they become more advanced. This direct visualization is what makes it such an invaluable tool in preventive medicine.

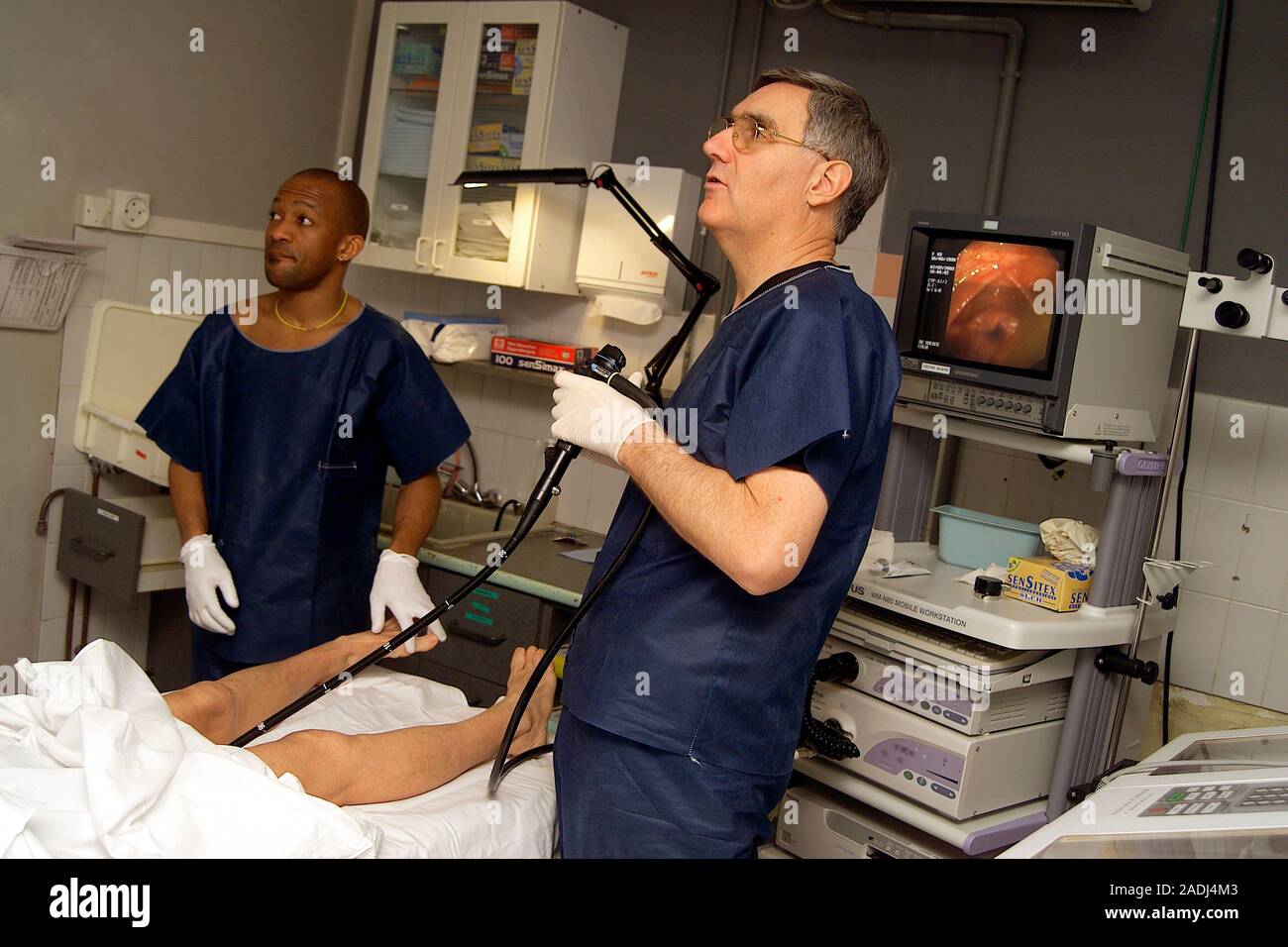

During a colonoscopy, a long, flexible tube known as a colonoscope is gently inserted into the rectum. This highly sophisticated instrument is equipped with a tiny video camera at its tip, which serves as your doctor’s eyes, allowing them to view the inside of the entire colon on an external monitor. This real-time, high-definition imagery provides an unparalleled level of detail, making it possible to meticulously inspect the lining of your colon for even the smallest abnormalities.

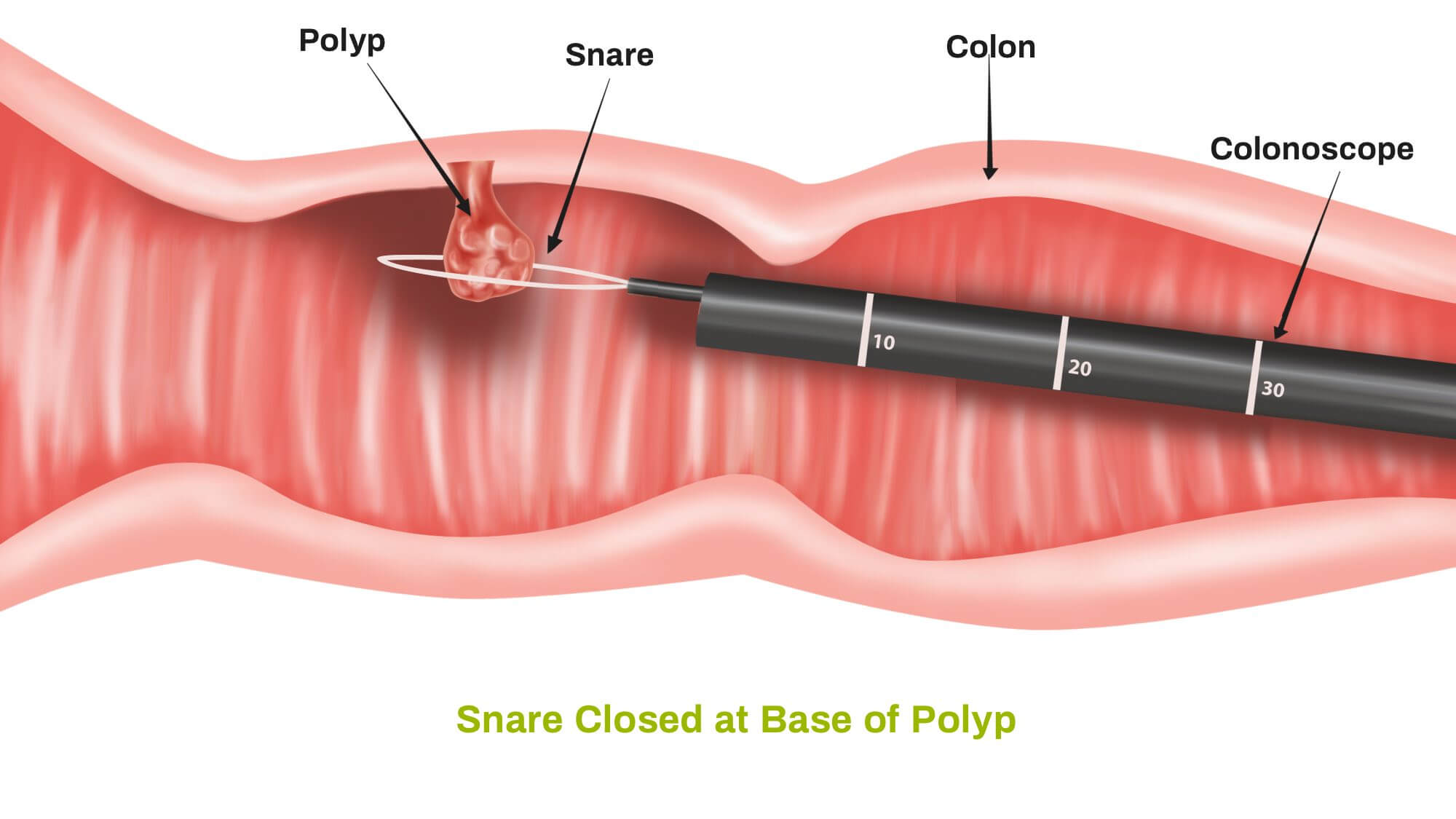

Beyond simply viewing, the colonoscope offers significant interventional capabilities. If necessary, polyps or other types of abnormal tissue can be removed directly through the scope during the colonoscopy itself. This immediate removal of potentially precancerous growths is a cornerstone of colorectal cancer prevention. Furthermore, tissue samples, known as biopsies, can also be taken during a colonoscopy, allowing for further laboratory analysis to determine their nature—whether they are cancerous, precancerous, or benign.

2. **The Critical Reasons Why It’s Done**Your doctor may recommend a colonoscopy for a variety of compelling reasons, each aimed at protecting or improving your digestive health. These reasons span from investigating current symptoms to proactive screening for serious diseases, making the procedure a versatile and vital component of modern healthcare. Understanding these indications can help clarify why this examination might be recommended for you.

One primary reason is to investigate intestinal signs and symptoms. If you’ve been experiencing issues such as abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, chronic diarrhea, or other persistent intestinal problems, a colonoscopy can help your doctor explore possible underlying causes. It provides a direct view of the affected areas, allowing for precise diagnosis and guiding subsequent treatment plans, which is often crucial for addressing discomfort and preventing further complications.

Perhaps the most widely known and critical reason for a colonoscopy, especially for Americans over 40, is to screen for colon cancer. Current guidelines from organizations like the American Cancer Society recommend that people at average risk of colorectal cancer, meaning those with no colon cancer risk factors other than age, start regular screening at age 45. For these individuals, your doctor may recommend a colonoscopy every 10 years. However, it’s important to note that if you have other risk factors, your doctor may recommend a screen sooner, and colonoscopy is one of a few effective options for colon cancer screening. A conversation with your doctor will determine the best screening strategy tailored to your personal health profile.

Furthermore, if you have a history of polyps, your doctor may recommend a follow-up colonoscopy specifically to look for and remove any additional polyps. This practice is absolutely vital, as it directly contributes to reducing your risk of developing colon cancer in the future. Polyps, while often benign initially, can evolve into cancerous growths over time, so their timely detection and removal are paramount. Sometimes, a colonoscopy may also be done for treatment purposes, such as placing a stent to alleviate an obstruction or removing an object from your colon, demonstrating its versatility beyond just diagnosis and screening.

Read more about: Your Ultimate Single Car Solution: The Best Picks for Every Driver in 2025

3. **Understanding the Minimal Risks Involved**While the thought of any medical procedure can naturally bring concerns about potential risks, it is reassuring to know that a colonoscopy poses few risks, making it an exceptionally safe procedure given its immense benefits. Medical professionals undertake rigorous precautions to ensure patient safety, and complications are exceedingly rare. Understanding these infrequent occurrences can help you contextualize any concerns and discuss them openly with your healthcare provider.

Rarely, complications of a colonoscopy may include a reaction to the sedative used during the exam. Modern anesthesiology is highly advanced, and medical teams closely monitor patients for any adverse responses. It’s important to disclose your full medical history and any known allergies to your doctor before the procedure to minimize such risks. This careful consideration of your individual health profile is a standard part of pre-procedure planning.

Another infrequent complication is bleeding from the site where a tissue sample (biopsy) was taken or a polyp or other abnormal tissue was removed. While a small amount of bleeding might occur, significant or persistent bleeding is uncommon. Your doctor will take all necessary steps to manage any bleeding during the procedure. Patients on blood-thinning medications will receive specific instructions on adjusting their dosages prior to the colonoscopy to mitigate this particular risk.

An even rarer, but more serious, complication is a tear in the colon or rectum wall, known as a perforation. This is an extremely unusual event, but it underscores the importance of having your colonoscopy performed by an experienced and skilled gastroenterologist. Before your procedure, your doctor will discuss all potential risks, no matter how remote, and you will be asked to sign a consent form giving permission for the procedure. This ensures you are fully informed and comfortable with the process, affirming a commitment to your safety and understanding of your care. It is vital to consult your doctor if you experience persistent abdominal pain or a fever after the procedure, as these could be signs of a rare complication that may occur immediately or, in very rare cases, be delayed for up to 1 to 2 weeks.

Read more about: Home Refinancing 101: Your Essential Guide to Knowing When to Refinance — And When to Hold Off for Bigger Savings

4. **The Essential Preparation: A Step-by-Step Guide**While the colonoscopy procedure itself is straightforward, the preparation phase is undeniably the most crucial step, directly influencing the accuracy and effectiveness of the examination. It’s often considered the most challenging part of the process, but adhering strictly to your doctor’s instructions is paramount. Any residue in your colon may make it difficult to get a good view of your colon and rectum during the exam, potentially leading to missed polyps or the need for a repeat procedure, which nobody wants!

To effectively empty your colon, your doctor will ask you to follow a special diet the day before the exam. Typically, this means you won’t be able to eat solid food. Your intake will be limited to clear liquids, which include plain water, tea and coffee without milk or cream, clear broth, and carbonated beverages. A critical instruction is to avoid red liquids, as these can easily be mistaken for blood during the colonoscopy, leading to confusion or misinterpretation of findings. Furthermore, you will generally not be able to eat or drink anything after midnight the night before the exam.

Accompanying the dietary restrictions is the requirement to take a laxative. Your doctor will usually recommend a prescription laxative, which typically comes in a large volume, either in pill form or as a liquid solution. In most instances, you will be instructed to take the laxative the night before your colonoscopy. However, some regimens may ask you to use the laxative both the night before and the morning of the procedure. While this part of the prep can be unpleasant, it is absolutely essential for achieving the clean colon necessary for a thorough examination.

Finally, adjusting your medications is a vital part of the preparation. It is imperative to remind your doctor of all your medications at least a week before the exam, especially if you manage conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, or heart problems, or if you take medications or supplements that contain iron. Particular attention must be paid if you take aspirin or other medications that thin the blood, such as warfarin (Coumadin, Jantoven); newer anticoagulants, such as dabigatran (Pradaxa) or rivaroxaban (Xarelto), which are used to reduce the risk of blood clots or stroke; or heart medications that affect platelets, such as clopidogrel (Plavix). Your doctor will provide specific guidance, as you may need to adjust your dosages or temporarily stop taking these medications to ensure your safety and the success of the procedure.

Read more about: Mastering Highway Exits: A Consumer Reports Guide to Safe, Smooth, and Stress-Free Departures Without Cutting Off Other Drivers

5. **What Happens During the Procedure?**Once you’ve completed the preparation phase, the actual colonoscopy procedure is designed to be as comfortable and efficient as possible, often taking less time than the prep itself. Understanding what happens during this period can further alleviate any anxieties you might have, allowing you to approach the experience with greater confidence.

Upon arrival, you’ll be provided with a gown to wear, but likely nothing else, to facilitate the examination. Sedation or anesthesia is almost always recommended to ensure your comfort throughout the procedure. In most cases, a sedative is combined with pain medication, which is administered directly into your bloodstream (intravenously). This combination works to significantly lessen any discomfort, allowing you to relax or even drift into a light sleep during the colonoscopy, making the experience far less daunting than anticipated.

You’ll begin the exam by lying on your side on the exam table, typically with your knees drawn toward your chest. This position helps the doctor to gently insert the colonoscope into your rectum. The colonoscope is a marvel of modern medical engineering, specifically designed to navigate the intricate path of your large intestine. It is long enough to reach the entire length of your colon and is equipped with a light and a tube (channel).

Through this channel, the doctor can pump air, carbon dioxide, or water into your colon. The purpose of this is to inflate the colon, which gently expands the intestinal walls and provides a much clearer, unobstructed view of the lining. As the scope is moved or air is introduced, you may feel some stomach cramping or the urge to have a bowel movement, but these sensations are usually mild and temporary, managed effectively by the sedation. The colonoscope also contains a tiny video camera at its tip, which sends real-time images to an external monitor so that the doctor can thoroughly study the inside of your colon, searching for any anomalies. Crucially, the doctor can also insert specialized instruments through the channel to take tissue samples (biopsies) or remove polyps or other areas of abnormal tissue on the spot, combining diagnostic and therapeutic actions within a single procedure. A colonoscopy typically takes about 30 to 60 minutes, a relatively short duration for such a comprehensive examination.

Read more about: Your Health, Your Voice: Essential Questions to Empower Every Doctor’s Visit

6. **Navigating the Post-Procedure Experience**As the colonoscopy concludes, the focus shifts to a smooth and comfortable recovery. The post-procedure phase is generally straightforward, but there are important guidelines to follow, particularly concerning the lingering effects of sedation and common bodily responses. Being prepared for what to expect after the exam can help ensure a restful and uneventful recovery.

After the exam, it typically takes about an hour for you to begin to recover from the sedative. However, the full effects of the sedative can take up to a full day to completely wear off. For this reason, it is absolutely essential that you arrange for someone to take you home from the facility. Furthermore, for the rest of the day, you must refrain from driving, making any important decisions, or returning to work. Prioritizing rest and avoiding activities that require full mental alertness is key to a safe recovery.

It is quite common to experience some mild symptoms for a few hours after the exam. You may feel bloated or pass gas as your body works to clear the air that was introduced into your colon during the procedure. This is a normal physiological response, and gentle walking can often help relieve any discomfort associated with the gas, encouraging its expulsion. These sensations are temporary and typically resolve quickly as your digestive system returns to its normal state.

You may also notice a small amount of blood with your first bowel movement after the exam. In most cases, this isn’t cause for alarm, especially if a biopsy was taken or a polyp was removed. However, vigilance is always important. You should consult your doctor without delay if you continue to pass blood or blood clots, or if you develop persistent abdominal pain or a fever. While complications are unlikely, it’s important to remember that these symptoms may occur immediately or, in some rare instances, be delayed for up to 1 to 2 weeks after the procedure. Your medical team is there to support you through every stage, so never hesitate to reach out if you have concerns about your recovery.

7. **Deciphering Your Colonoscopy Results**Once your colonoscopy is complete, a crucial step in your health journey is understanding the results. Your doctor, often a gastroenterologist, will thoroughly review the findings from the examination and will then share this information with you in a clear and comprehensible manner. This discussion forms the basis for any subsequent recommendations or actions, reinforcing the personalized nature of your healthcare.

A colonoscopy is considered to have a “negative result” if the doctor does not find any abnormalities within your colon. This is excellent news, indicating a healthy colon. In such cases, if you are at average risk of colon cancer and have no risk factors other than age, or if only benign small polyps were found and removed, your doctor will generally recommend that you have your next colonoscopy in 10 years. This standard interval reflects the confidence in a clean bill of health and the slow growth rate of most precancerous lesions.

However, a negative result might sometimes come with a caveat. If there was residual stool in the colon that prevented a complete and thorough examination, your doctor may recommend a repeat colonoscopy sooner than the standard 10 years. The timing of this repeat procedure will depend on the amount of stool present and how much of your colon was able to be seen. To ensure a clearer view next time, your doctor may also recommend a different bowel preparation regimen, underscoring the vital role of preparation in obtaining accurate results.

A “positive result” occurs if the doctor finds any polyps or other abnormal tissue in your colon during the examination. It’s important to remember that finding polyps is not necessarily a diagnosis of cancer. In fact, most polyps are not cancerous, though some can be precancerous, meaning they have the potential to develop into cancer over time. Any polyps or abnormal tissues removed during your colonoscopy are sent to a laboratory for detailed analysis by a pathologist, who determines whether they are cancerous, precancerous, or noncancerous (benign).

Based on the size, number, and specific cellular characteristics (histology) of any polyps found, along with other risk factors, your doctor will recommend a tailored surveillance schedule. For instance, if you had one or two polyps less than 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) in diameter, a repeat colonoscopy in 7 to 10 years might be suggested, depending on your other risk factors. However, if you had more than two polyps, a large polyp (larger than 0.4 inch), polyps with certain cell characteristics indicating a higher risk of future cancer, or cancerous polyps, your doctor will recommend another colonoscopy much sooner. If a polyp or abnormal tissue couldn’t be removed during the initial procedure, a repeat exam with a gastroenterologist specializing in large polyp removal or even surgery might be necessary.

8. **Screening Guidelines for Average-Risk Individuals Over 45**For many Americans, the question isn’t just whether to get a colonoscopy, but when and how often. Fortunately, clear guidelines exist, especially for individuals considered to be at average risk for colorectal cancer. These recommendations are designed to catch potential issues early, when they are most treatable, or even prevent them from forming in the first place.

The American Cancer Society recommends that people at average risk of colorectal cancer begin regular screening at age 45. Similarly, the US Preventive Services Task Force (Task Force) recommends that adults aged 45 to 75 be screened for colorectal cancer. Individuals are generally considered to be at average risk if they do not have a personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps, a family history of colorectal cancer, a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease), a confirmed or suspected hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, or a personal history of receiving radiation to the abdomen or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer. For those in good health with a life expectancy of more than 10 years, regular colorectal cancer screening should continue through age 75. Beyond age 75, the decision to screen should be made on an individual basis in consultation with your doctor.

Several effective screening options are available for average-risk individuals. Colonoscopy is a highly recommended option, typically performed every 10 years if no abnormalities are found. However, it’s not the only approach. Other visual (structural) exams include CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) every 5 years, and flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years (or every 10 years with an annual Fecal Immunochemical Test, FIT). Stool-based tests are also available, such as the highly sensitive FIT annually, the highly sensitive guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) annually, or a multi-targeted stool DNA test (MT-sDNA or FIT-DNA) every 3 years.

While these options offer flexibility, the most important message is to get screened, regardless of which test you choose. It’s crucial to discuss these options with your healthcare provider to determine the best strategy tailored to your personal health profile and insurance coverage. It’s also important to understand that if a person chooses to be screened with a test other than a colonoscopy, any abnormal test result should always be followed up with a timely colonoscopy to complete the screening process and investigate the findings further.

9. **Tailored Screening for Increased or High-Risk Individuals**While general guidelines provide a solid framework for average-risk individuals, not everyone fits neatly into that category. For those with increased or high-risk factors for colorectal cancer, screening protocols become more specific and often involve earlier initiation, more frequent examinations, and sometimes, a particular type of screening test. This tailored approach is crucial for optimizing detection and prevention in vulnerable populations.

Individuals are typically considered to be at increased or high risk if they have a strong family history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps, a personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps, a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease), a known family history of a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome (like familial adenomatous polyposis, FAP, or Lynch syndrome), or a personal history of radiation to the abdomen or pelvic area for a prior cancer. These factors significantly elevate the lifetime risk, necessitating a more vigilant screening strategy.

For those with one or more family members who have had colon or rectal cancer, screening recommendations depend on who in the family had cancer and their age at diagnosis. In some cases, individuals might still follow average-risk guidelines, but often, a colonoscopy (and not other types of tests) is recommended more frequently, possibly starting before age 45—for example, at age 40 or 10 years before the youngest affected relative’s diagnosis, whichever comes first. Similarly, individuals who have had certain types of polyps removed during a colonoscopy generally need another colonoscopy after 3 years, though this can vary. If you’ve had colon or rectal cancer, regular colonoscopies are typically needed about 1 year after surgery, then every 3 years. For those with a history of radiation to the abdomen or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer, colorectal screening often begins 10 years after the radiation was given or at age 35 (whichever comes last) and may be needed as often as every 3 to 5 years.

Individuals with inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, are considered high risk and generally require colonoscopies, not other types of tests. Screening typically starts at least 8 years after their IBD diagnosis, with follow-up colonoscopies every 1 to 3 years depending on their specific risk factors and prior findings. Similarly, those with known or suspected genetic syndromes like FAP or Lynch syndrome require colonoscopies, often beginning at a very young age—potentially even in the teenage years for some syndromes—and performed much more frequently than for average-risk individuals.

Given the complexity of these high-risk scenarios, it is paramount to have a comprehensive discussion with your healthcare provider. They can assess your individual risk factors, help you understand the nuances of various guidelines, and suggest the most appropriate screening option and schedule for you. This personalized consultation ensures that your screening strategy is optimally aligned with your unique health needs and risk profile.

10. **The Unseen Heroes: Polyps and Their Significance**Within the context of colorectal cancer prevention, polyps are truly the “unseen heroes” – or rather, the silent precursors whose early detection and removal can be life-saving. Colorectal cancer almost invariably develops from precancerous polyps, which are abnormal growths that form on the lining of the colon or rectum. The beauty of colonoscopy as a screening tool lies in its ability to find these polyps, allowing for their removal before they have the chance to transform into cancerous lesions.

It’s important to understand that not all polyps are created equal. While most polyps are benign (non-cancerous) initially, some possess characteristics that classify them as precancerous, meaning they have the potential to become malignant over time. When polyps or abnormal tissues are removed during a colonoscopy, they are meticulously sent to a laboratory for pathological analysis. This crucial step determines their precise nature: whether they are cancerous, precancerous, or entirely noncancerous, guiding subsequent surveillance strategies.

The type, size, and number of polyps are all significant factors in determining future risk and screening intervals. For instance, “hyperplastic polyps” are generally benign and, if few in number, may not necessitate an accelerated screening schedule. However, findings such as a “Tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia” are far more concerning, indicating a polyp with a greater potential to become cancerous, thus warranting a much sooner follow-up colonoscopy. “Sessile polyps,” which adhere closely to the colon wall, may also influence the recommendation for earlier re-screening due to their morphology.

The timely detection and removal of polyps, especially precancerous ones, is a cornerstone of colorectal cancer prevention. By identifying and excising these growths during a colonoscopy, medical professionals are actively interrupting the progression of disease. This prophylactic measure transforms a potentially life-threatening diagnosis into a manageable intervention, underscoring the profound significance of these often-small, silent growths and the procedure designed to address them.

11. **Colonoscopy as a Premier Screening Modality: Why It Stands Out**When discussing options for colorectal cancer screening, the colonoscopy frequently rises to the top as a premier modality, and for very compelling reasons. Its distinct advantages in both diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic capability set it apart from other available screening methods, offering an unmatched level of comprehensive care in a single procedure.

The most significant factor distinguishing colonoscopy is its dual functionality. It is the only “one-step” colorectal cancer screening modality because it serves both as a diagnostic procedure for the entire colon and as a therapeutic intervention. During the examination, the doctor can not only visually identify polyps or other abnormal tissues but also remove most of them immediately. This seamless integration of diagnosis and treatment within the same appointment means that potential cancers are not just detected, but often prevented or excised on the spot, eliminating the need for a separate follow-up procedure for polyp removal.

Furthermore, colonoscopy boasts near-perfect accuracy in detecting colorectal cancer. Its direct visualization of the entire colon allows for a meticulous inspection of the intestinal lining, making it highly effective at identifying even subtle abnormalities. This robust detection capability translates into tangible, life-saving outcomes. Research indicates that the use of colonoscopy for screening significantly reduces colorectal cancer incidence by 69% and colorectal cancer mortality by a remarkable 68%, making a compelling case for its preventative power.

While other screening tests like stool-based analyses, flexible sigmoidoscopy, or CT colonography offer valuable initial screening, they often require a colonoscopy as a follow-up if an abnormal result is found. Stool tests, though non-invasive and home-based, have lower sensitivity for advanced adenomas and do not detect serrated lesions, and their impact on CRC incidence and mortality is still being fully understood compared to colonoscopy. Flexible sigmoidoscopy only provides direct visualization of the distal colon, leaving a significant portion of the colon unexamined. CT colonography, while less invasive, can have lower sensitivity for certain types of polyps, particularly flat and sessile serrated lesions.

Ultimately, the ability of a colonoscopy to provide a complete view of the entire colon, detect abnormalities with high precision, and simultaneously remove precancerous polyps during the same procedure makes it an invaluable and often superior tool in the fight against colorectal cancer. It offers a comprehensive and proactive approach that empowers both patients and healthcare providers in managing long-term digestive health.

12. **The Paramount Importance of Proper Bowel Preparation**While the procedure itself is relatively brief and made comfortable with sedation, it cannot be overstated that the success and accuracy of a colonoscopy hinge almost entirely on one critical factor: proper bowel preparation. This phase, though often considered the most challenging part of the process, is absolutely paramount because any residue remaining in your colon can obscure the doctor’s view, making it difficult or even impossible to detect polyps or other abnormalities.

Imagine trying to find a small object in a cluttered room – the task becomes exponentially harder if the room hasn’t been tidied. Similarly, if your colon is not thoroughly cleaned out, even significant polyps or early-stage cancers can be missed, undermining the entire purpose of the screening. This poor visibility not only compromises the quality of the examination but also carries the risk of needing a repeat procedure, which nobody desires after undergoing the initial preparation.

Medical professionals frequently emphasize that a poorly prepped colon is a significant obstacle to effective screening. As noted by experts, “If the prep wasn’t done properly and there is still a lot of stool present, I’ll mark on the patient’s colonoscopy report that the preparation of the colon was poor.” This formal documentation of inadequate preparation can directly lead to a recommendation for a repeat colonoscopy sooner than planned, often with a different, perhaps more intensive, bowel preparation regimen to ensure a better outcome the second time around. This highlights that the effort invested in preparation is a direct investment in the reliability of your health assessment.

Therefore, strict adherence to your doctor’s instructions for diet, laxative use, and medication adjustments is not merely a suggestion—it is a non-negotiable requirement for a successful colonoscopy. While the experience of bowel preparation may be unpleasant, completing it correctly provides your doctor with the best possible chance of finding polyps and detecting colorectal cancer early, ultimately maximizing the preventive and diagnostic power of the procedure. It’s a temporary inconvenience for a potentially life-saving benefit.

Read more about: Understanding the Journey: Common Changes Your Body Experiences When Nearing the End of Life

As we conclude this in-depth exploration, it’s clear that the colonoscopy, far from being a procedure to dread, is a vital ally in your long-term health. It represents a proactive and powerful defense against colorectal cancer, a disease that is highly preventable and curable when detected early. By demystifying the process, from preparation to understanding results, our aim has been to empower you with knowledge, transforming apprehension into confidence. Embrace the colonoscopy not as a daunting medical task, but as a crucial step in safeguarding your well-being, ensuring a healthier future for yourself and your loved ones. Your health is worth this essential investment.