“Whatever became of them?” That’s a question many of us ponder when we think about the final resting places of history’s most fascinating figures. While most expect a dignified and complete burial, the sheer number of instances where parts of famous bodies have become separated, going on their own peculiar adventures, is truly astonishing. It turns out that some individuals achieve a second, unexpected kind of fame long after their last breath.

The human body, post-mortem, can take on a life of its own, quite literally. From stolen hearts and misplaced skulls to a king’s vertebra used as a dinner party prop, the stories are as bizarre as they are captivating. These aren’t just macabre tales; they offer a unique glimpse into historical practices, the eccentricities of collectors, and the enduring human fascination with celebrity, even in death.

Prepare yourself for a journey through the annals of history, where we unearth the strangest afterlives of some very famous body parts. We’re talking about limbs, organs, and even single bones that defied the grave, embarking on journeys that are far wilder than anything their original owners ever experienced. It’s time to discover what became of these remarkable relics.

1. **Queen Anne Boleyn’s Heart**: The tragic end of Queen Anne Boleyn, beheaded in 1536 on the strict orders of her husband, King Henry VIII, is a well-known chapter in English history. What fewer people realize, however, is that her story didn’t quite end with her execution. In a truly astonishing turn of events, her heart was secretly stolen from her body and hidden away in a church located near Thetford, Norfolk. It was an act of both defiance and devotion, ensuring that a piece of the ill-fated queen lived on outside her official burial.

This hidden relic remained concealed for centuries, a secret held within the ancient walls of the church. It wasn’t until 1836, nearly 300 years after her death, that Queen Anne’s heart was dramatically rediscovered. Its finding surely caused a stir among those who knew the history. Following this unexpected re-emergence, the heart was given a more formal, albeit still somewhat secretive, re-burial. It was laid to rest once more, this time beneath the church organ, where it is said to remain to this very day. A quiet, yet profound, testament to a queen whose life was cut short, but whose heart found an enduring, albeit separate, resting place.

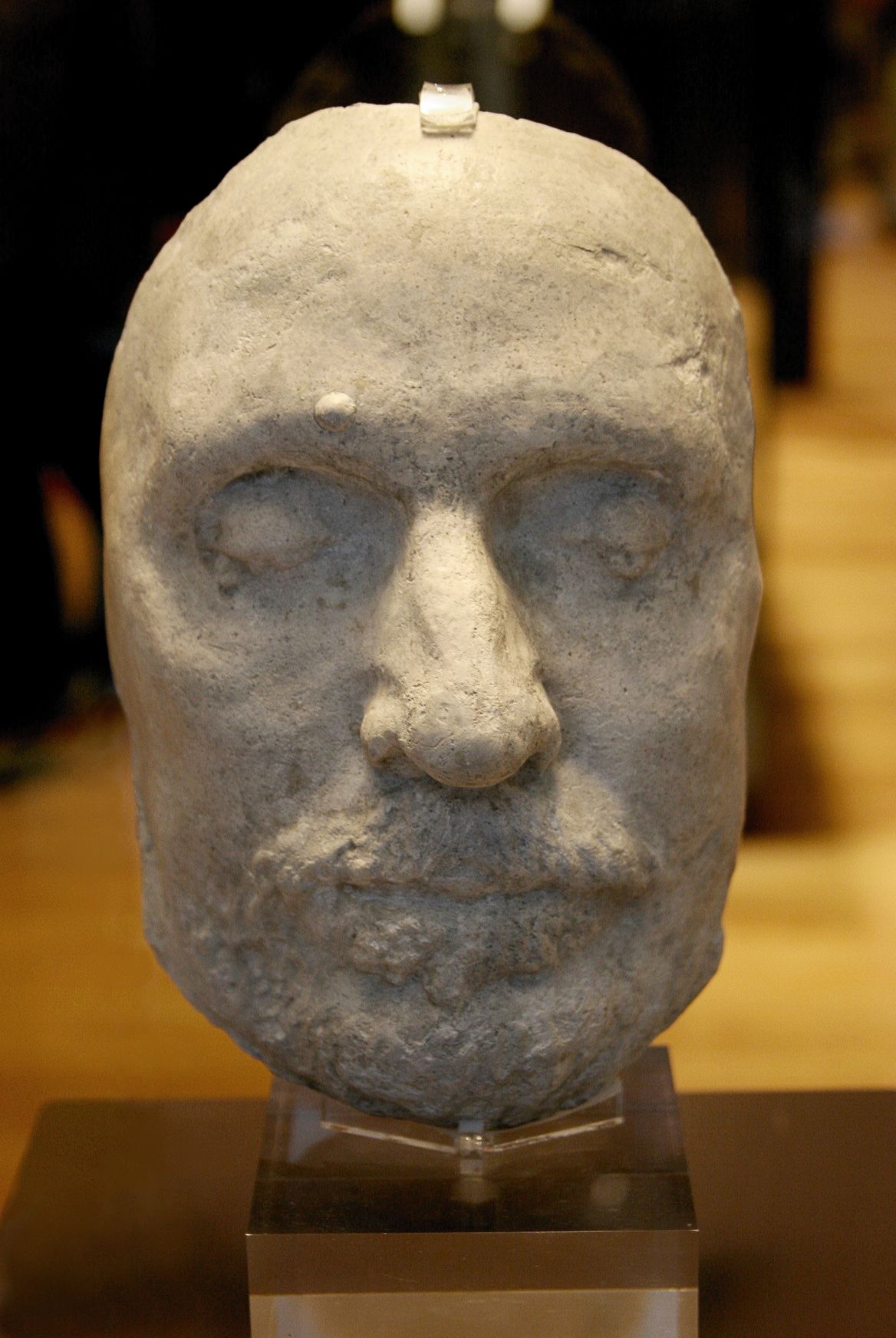

2. **Sir Thomas More’s Head**: The year 1535 saw another high-profile beheading ordered by King Henry VIII, that of Sir Thomas More. His crime? A steadfast refusal to acknowledge the legality of the king’s marriage to Anne Boleyn. After his execution, More’s head was subjected to a gruesome fate, common for traitors of the time: it was taken from the scaffold, parboiled, then impaled on a pole and prominently exhibited on London Bridge for all to see. A stark warning to anyone contemplating defiance against the crown.

However, devotion can be a powerful force, even in the face of such grim spectacles. Sir Thomas More had a fiercely devoted daughter, Margaret Roper, who could not bear to see her father’s head remain as a public spectacle. She ingeniously bribed the bridge-keeper to dislodge the head, allowing her to smuggle it home. Margaret went to extraordinary lengths to preserve the head, treating it with spices, though this act of piety was eventually betrayed by spies, leading to her brief imprisonment before her release.

Margaret Roper remained a guardian of her father’s legacy, and when she died in 1544, Sir Thomas’ head was buried alongside her. But the story doesn’t end there. In 1824, her vault was opened, and to the surprise of many, More’s head was once again brought into public view, displayed in St. Dunstan’s Church in Canterbury for a considerable period. His journey from public display on London Bridge to a private family heirloom and then back to a public exhibit speaks volumes about the enduring fascination with this pivotal historical figure.

3. **Oliver Cromwell’s Head**: Oliver Cromwell, the formidable Lord Protector of England, died in 1658, and was initially given a lavish funeral, embalmed and laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. However, his posthumous peace was short-lived. Following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, the new regime sought retribution against those responsible for the execution of King Charles I. Cromwell’s body was dramatically disinterred, dragged to Tyburn, and subjected to the macabre practice of gibbeting, a public display meant to deter others, where it was left hanging until sundown.

The indignity continued as the public executioner then cut down the body and severed Cromwell’s head. This head was subsequently impaled on a 25-foot pole, placed atop the roof of Westminster Hall, where it remained for over 24 years, from 1660 to 1685. It was a potent symbol of royal vengeance, exposed to the elements for decades. Eventually, during a powerful gale in 1685, the head was dislodged from its perch and fell. A soldier, opportunistic or perhaps simply curious, found the head and chose to hide it away in his chimney, initiating a new, even more private chapter in its journey.

From that point, Cromwell’s head embarked on an incredibly long and strange odyssey. The soldier bequeathed it to his daughter, and by 1710, it shockingly appeared in a “Freak Show,” advertised as “The Monster’s Head!” For years, it passed through numerous private owners, its value increasing, until it was acquired by a Dr. Wilkinson. In 1960, the Wilkinson family offered the head to Sydney Sussex College, Cromwell’s alma mater. Here, after centuries of bizarre journeys, Oliver Cromwell’s head was finally given a dignified burial in a secret location within the college grounds, ensuring it would never again be subjected to such strange exhibition. The remarkable story of Cromwell’s head, still with preserved flesh, reflects a chaotic period of English history and the enduring power of relics.

4. **King Charles I’s Fourth Cervical Vertebra**: The story of King Charles I’s beheading in 1649 is, like Cromwell’s, a grim but well-known event in British history. His body was subsequently buried at Windsor Castle, sharing a vault with none other than Henry VIII. The remains rested undisturbed for over a century and a half until 1813, when the coffin was opened, and Sir Henry Halford, the royal surgeon, was tasked with performing an autopsy on the body.

What transpired next was an act of extraordinary, and rather macabre, audacity. During the autopsy, Sir Henry secretly, and without permission, stole Charles’ fourth cervical vertebra, the very bone that would have connected to the point of his execution. For the next three decades, this bone became his peculiar party trick. Sir Henry reportedly loved to “shock his friends at dinner parties by using the vertebra as a salt holder,” turning a piece of royal history into a morbid conversation starter.

Such an unusual souvenir could not remain a secret forever. When news of Sir Henry’s strange possession reached Queen Victoria, she was, understandably, outraged. She immediately “demanded that the bone be returned to Charles’ coffin,” and to her credit, “It was!” This swift royal intervention brought an end to the vertebra’s bizarre public life, ensuring that a piece of the executed monarch was finally reunited with his remains, albeit after a truly wild detour into a surgeon’s private dining room.

5. **Louis XIV of France’s Heart**: Louis XIV, the iconic “Sun King” and one of France’s most powerful monarchs, died in 1715. His official burial was meant to be solemn and complete, but the tumultuous events of the French Revolution, decades later, brought chaos even to the dead. During this period, the tomb of the French king was senselessly wrecked and plundered, leading to the desecration of royal remains. Amidst this upheaval, Louis XIV’s embalmed heart was stolen, setting it on a path to one of history’s most bizarre post-mortem journeys.

The stolen heart soon found its way into the hands of collectors, a curious commodity in the macabre market of historical relics. It was sold to Lord Harcourt, an English nobleman who evidently harbored a peculiar fascination with the Sun King. Lord Harcourt, in turn, sold the heart to the Dean of Westminster, the Very Reverend William Buckland. Buckland was no ordinary clergyman; he was known for his eccentricities, particularly his unusual culinary experiments. The context states he “liked to experiment with food” and that he “had made it his life’s mission to taste every animal he could.”

One night, at a dinner party, the dean’s peculiar interests reached their zenith. With Lord Harcourt as a guest, Buckland was shown the embalmed heart of Louis XIV. Without hesitation, the Dean, true to his word about tasting everything, “ate the embalmed heart!” This shocking act cemented the heart’s place in the annals of historical oddities. Louis XIV is now buried in the Saint-Denis basilica, a national monument in France, but his heart remains famously, and perhaps infamously, absent, consumed by an eccentric English dean.

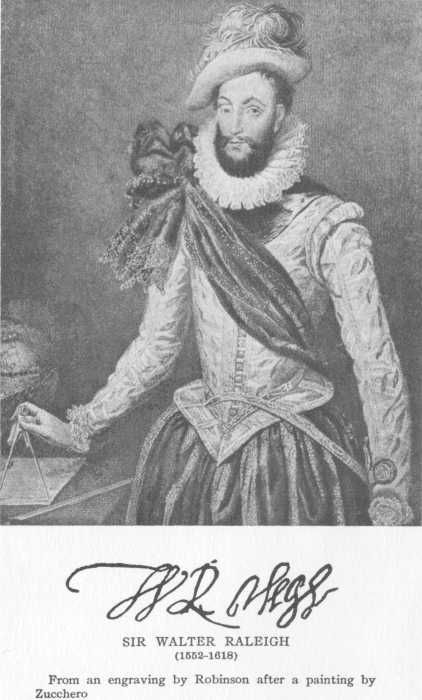

6. **Sir Walter Raleigh’s Head**: Sir Walter Raleigh, the renowned English adventurer, writer, and courtier, met his end by execution in 1618. Following his execution, Raleigh’s body was buried, as was customary. However, his embalmed head did not accompany his body to the grave. Instead, it was kept by his devoted wife, Elizabeth Throgmorton, for the remainder of her life. This was not a quick act of grieving, but a prolonged dedication; she reportedly kept the head in a red leather bag, constantly by her side, for the last 29 years of her life.

Upon Elizabeth’s death, the macabre inheritance passed to their son, Carew Raleigh, who continued the family tradition of keeping his father’s preserved head. Carew diligently took care of the relic until his own death in 1666. It seems the intention was to finally reunite father and son in death, as Carew was buried in his father’s grave, with Sir Walter’s head presumably accompanying him. It might have seemed like the final resting place for this unique family heirloom.

However, the story of Sir Walter’s head was far from over. In 1680, Carew Raleigh’s body was exhumed and subsequently reburied. Crucially, the text notes that he was reburied “with his father’s head,” this time in West Horsley, Surrey. This final documented movement confirms that the head remained with the family, a lasting, tangible link to a significant figure in Elizabethan and Jacobean history, enduring separation from its original body through multiple generations and re-interments.

The journey through history’s most unexpectedly mobile body parts continues, revealing more bizarre tales of what happened after the last breath. From ancient bog finds to philosophical relics and royal heart-stopping feasts, these stories are a testament to humanity’s enduring fascination with the famous, even in their fragmented forms. Prepare to delve deeper into the peculiar afterlives that defied the grave.

7. **The Tollund Man’s Big Toe**: In 1950, Denmark yielded an archaeological marvel: the Tollund Man, a bog body remarkably preserved for roughly 2,400 years. His head, still retaining visible hair and beard stubble, was in exceptional condition. However, the technology of 70 years ago presented a challenge in removing the entire body intact, leading to a compromise: save the head, while the rest of the body was excavated, autopsied, and cut into smaller pieces for research, sent to various locations.

With the head being the unquestionable centerpiece, careful tracking of the other body parts became a secondary concern, and soon, pieces began to go missing. Decades later, in the 1980s, scholars initiated an ambitious effort to reassemble the body. After years of dedicated work, nearly all the parts were recovered, save for the internal organs and, curiously, the big toe from the right foot, which had clearly been sawed off.

The mystery of the missing toe persisted until 2016, when a surprising phone call arrived at the museum from Birte Christensen. She revealed herself as the daughter of the late Brorson Christensen, a conservator instrumental in preserving the Tollund Man’s head. While working on the bog body, her father had cut off the toe specifically to study different preservation techniques. As nobody ever requested its return, he simply kept it in a jar of blue liquid on his desk until his death, bringing an unexpected end to the big toe’s long and liquid journey.

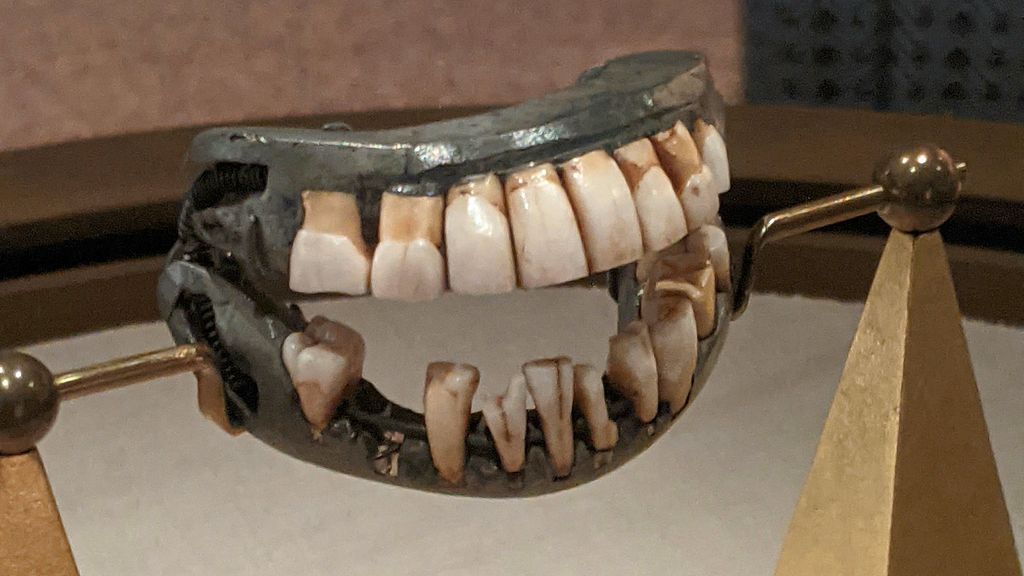

8. **Washington’s Last Tooth**: George Washington, the revered Founding Father of the United States, famously suffered from extensive dental problems throughout his life, starting with toothaches and decay in his 20s. These issues worsened with age, causing him frequent pain and necessitating the use of multiple dentures. Contrary to popular myth, none of these dentures were ever made of wood. His initial set, crafted by Dr. John Baker before the Revolutionary War, was actually made of ivory.

Later, Washington engaged the services of a French dentist, Jean-Pierre Le Mayeur, but eventually, Dr. John Greenwood became the president’s dedicated personal dentist. By the time Washington assumed the presidency, he had only one natural tooth remaining. Greenwood, adhering to his belief that a tooth should never be extracted if it could be saved, painstakingly designed all of Washington’s dentures with a special hole to accommodate this solitary tooth, using it as a crucial anchor for the prosthetic.

Inevitably, however, the last tooth was also lost. As a gesture of profound appreciation, Washington gifted this unique memento to John Greenwood. Greenwood cherished the tooth, keeping it in a special locket that he carried with him at all times. This extraordinary relic now forms part of the esteemed collection at the New York Academy of Medicine, a tangible link to the first president’s often painful, yet meticulously documented, dental history.

9. **Galileo’s Middle Finger**: Few Italian scientists hold as much historical significance as Galileo Galilei, the pioneering astronomer whose heliocentric theories famously landed him in hot water with the Catholic Church. Today, visitors to the Museo Galileo in Florence, formerly known as the Institute and Museum of the History of Science, can explore a remarkable collection of artifacts he used to make his groundbreaking discoveries. And among these scientific instruments, encased in a glass egg, lies an unexpected human relic: Galileo’s middle finger.

The story of how this digit came to be on display is as intriguing as it is peculiar. In 1737, almost a century after Galileo’s death, a group of his ardent admirers orchestrated the exhumation of his body to re-inter him in a more fitting mausoleum within the Santa Croce chapel itself. During this process, they seized the opportunity to take a few “keepsakes,” illicitly removing three of Galileo’s fingers and his last remaining tooth.

The middle finger was initially kept by Florentine antiquarian Anton Francesco Gori, before passing through the hands of various scientific institutes. In 1927, it finally came into the possession of the Museum of the History of Science, where it has been on display ever since, marking it as the sole human remains exhibited in a museum otherwise dedicated to scientific instruments. A fascinating twist occurred in 2009, when the other missing fingers and the tooth, long thought lost for nearly 300 years, mysteriously reemerged, were sold at auction, and eventually reunited with the middle finger, completing this macabre, yet historically significant, collection.

10. **Ludwig van Beethoven’s Hair**: Ludwig van Beethoven, the iconic German composer, was renowned for his profound musical genius, yet his life was a constant struggle against a litany of ailments, including severe stomach aches, persistent eye infections, and agonizing kidney stones, all compounded by his famously progressive deafness and debilitating mood swings. For centuries, the precise causes of his suffering remained a medical enigma.

However, a crucial piece of the puzzle emerged through a most unexpected relic: a lock of his hair. Just prior to Beethoven’s death in 1827, a teenager named Ferdinand Hiller acquired a lock of the composer’s hair, a common practice among admirers of famous figures. This seemingly innocuous keepsake was passed down through generations until 1994, when it was put up for auction. Its acquisition led to scientific study, and the findings were nothing short of astonishing.

The analysis revealed an alarmingly high concentration of lead, with the hair containing 42 times the amount typically found in human hair. Lead toxicity is well-known to manifest with symptoms such as abdominal pains, severe mood swings, and, critically, hearing loss. This remarkable discovery provided a compelling explanation for Beethoven’s lifelong health struggles, including his tragic deafness. Today, this historic lock of hair, a silent witness to a genius’s torment, is meticulously preserved at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., a tangible link to one of music’s most enduring mysteries.

The peculiar afterlives of these famous body parts offer a unique, sometimes unsettling, glimpse into history, human fascination, and the odd turns of fate. From a toe preserved in a jar to a skull at a dinner party, these fragments continue to tell tales that echo across centuries, ensuring their owners, or at least pieces of them, remain eternally famous. Their journeys remind us that even in death, some stories are far from over, and the past, in its own quirky way, can still surprise us.