Stepping into the vibrant tapestry of Ukrainian identity is an utterly fascinating journey, revealing a people whose history is as rich and complex as their culture is distinctive and enduring. Far from being a monolithic entity, the Ukrainians, or `українці` as they are known in their native tongue, embody a captivating blend of influences forged over centuries, reflecting their deep roots as an East Slavic ethnic group with a global footprint.

From the very name itself, `Ukraintsi`, derived from `Ukraina`, we begin to unearth layers of meaning. First documented in the Kievan Chronicle in 1187, the term evokes both a sense of “homeland” — `nash rodnoi kraj` — and of “edge” or “borderland,” suggesting a profound connection to their geographical position. Yet, another compelling theory posits `ukraina` as a “cut-off piece of land,” subtly hinting at “our land” or “land allotted to us,” a powerful testament to ownership and belonging.

Historically, the people inhabiting the territories of modern-day Ukraine have been known by various appellations, reflecting the shifting tides of foreign rule. Under the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Habsburg monarchy, they were often referred to as Ruthenians, a name echoing the ancient territory of Ruthenia. Those living within the Russian Empire, meanwhile, found themselves designated as Little Russians, a term now widely regarded as a humiliating imperialist imposition, though it persisted in official contexts.

The adoption of the ethnonym `Ukrainian` truly blossomed following the Ukrainian national revival of the late 18th century, a period marked by a profound resurgence of national traditions and culture. The publication of Ivan Kotliarevsky’s `Eneyida` in 1798, which notably established the modern Ukrainian language, played a pivotal role in this transformation, gradually replacing older terms like `Rusyns` and `Ruthenian(s)` and cementing `Ukrainians` as the dominant self-identification.

This vibrant national consciousness is deeply intertwined with the legacy of the Cossacks, who are frequently emphasized in modern Ukrainian identity and symbolism, even echoing in the Ukrainian national anthem. Their historical presence, particularly the establishment of the Zaporozhian Sich, fostered a distinct sense of self that resisted external definitions, with peasants continuing to refer to their land as “Ukraine” and themselves as Ruthenians, even when the Ukrainian language faced suppression.

Geographically, the Ukrainian spirit radiates far beyond its national borders. While the vast majority of ethnic Ukrainians naturally reside in Ukraine itself, constituting over three-quarters of the population, a truly remarkable diaspora stretches across the globe, reaching more than one hundred and twenty countries. This extensive spread makes Ukrainians one of the world’s largest diasporas, a testament to their mobility and enduring cultural ties.

The largest community outside of Ukraine resides in Russia, where approximately 1.9 million Russian citizens identify as Ukrainian, with millions more possessing Ukrainian ancestry, particularly in southern Russia and Siberia. Interestingly, inhabitants of the Kuban region have historically navigated complex identities, vacillating between Ukrainian, Russian (an identity bolstered by the Soviet regime), and “Cossack.” Even as far as the Russian Far East, an area historically known as “Green Ukraine,” about 800,000 people of Ukrainian ancestry have made their home.

Beyond Eurasia, North America hosts a significant Ukrainian presence, with an estimated 2.4 million people of Ukrainian origin across Canada and the United States, enriching the cultural fabric of these nations. Further south, Brazil boasts a community of 600,000, while Kazakhstan, Moldova, and Argentina also host hundreds of thousands of individuals identifying with Ukrainian heritage. Even across Europe, from Germany and Italy to Belarus, the Czech Republic, Spain, and Romania, substantial Ukrainian communities thrive, alongside smaller but equally significant populations in Latvia, Portugal, France, and Australia, among others.

The origins of the Ukrainian people are a fascinating blend of ancient lineages, rooted deeply in the genetic history of Europe. Like most Europeans, Ukrainians largely descend from three distinct ancestral groups. These include the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, whose presence dates back to the Paleolithic Epigravettian culture, laying the earliest foundations of the population.

Following them were the Neolithic Early European Farmers, who embarked on their migrations from Anatolia some 9,000 years ago during the transformative Neolithic Revolution, bringing with them agricultural innovations and new genetic markers. The third significant wave came from the Yamnaya Steppe pastoralists, who expanded into Europe from the Pontic–Caspian steppe, an area encompassing parts of modern Ukraine and southern Russia, about 5,000 years ago, profoundly shaping the Indo-European migrations.

A comprehensive survey of 97 Ukrainian genomes revealed an astonishing diversity, uncovering over 13 million genetic variants. Nearly 500,000 of these variants were previously undocumented, suggesting they are unique to this population, a remarkable finding that highlights the distinct genetic signature of Ukrainians. Furthermore, medically relevant mutations show different prevalences compared to other European genomes, particularly those from Western Europe and Russia.

Genetically, Ukrainian genomes form a single cohesive cluster, beautifully positioned between Northern and Western European populations in principal component analysis. There’s also a notable overlap with Central European populations and those from the Balkans, illustrating complex historical migrations and interactions. The most prevalent Y-haplogroups among Ukrainians are R1a (43%), largely R1a-Z282, which is found significantly only in Eastern Europe, followed by I2a (23%) and R1b (8%), among others.

Intriguingly, the Chernivtsi Oblast stands out as the only region where Haplogroup I2a is more frequent than R1a, a pattern more typical of the Balkan region. In a broader comparison, Ukrainians share a similar percentage of Haplogroup R1a-Z280 with their northern and eastern neighbors, like Belarusians, Russians, and Lithuanians. Moreover, their genetic pattern most closely resembles that of Belarusians, underscoring a shared lineage and regional genetic flow.

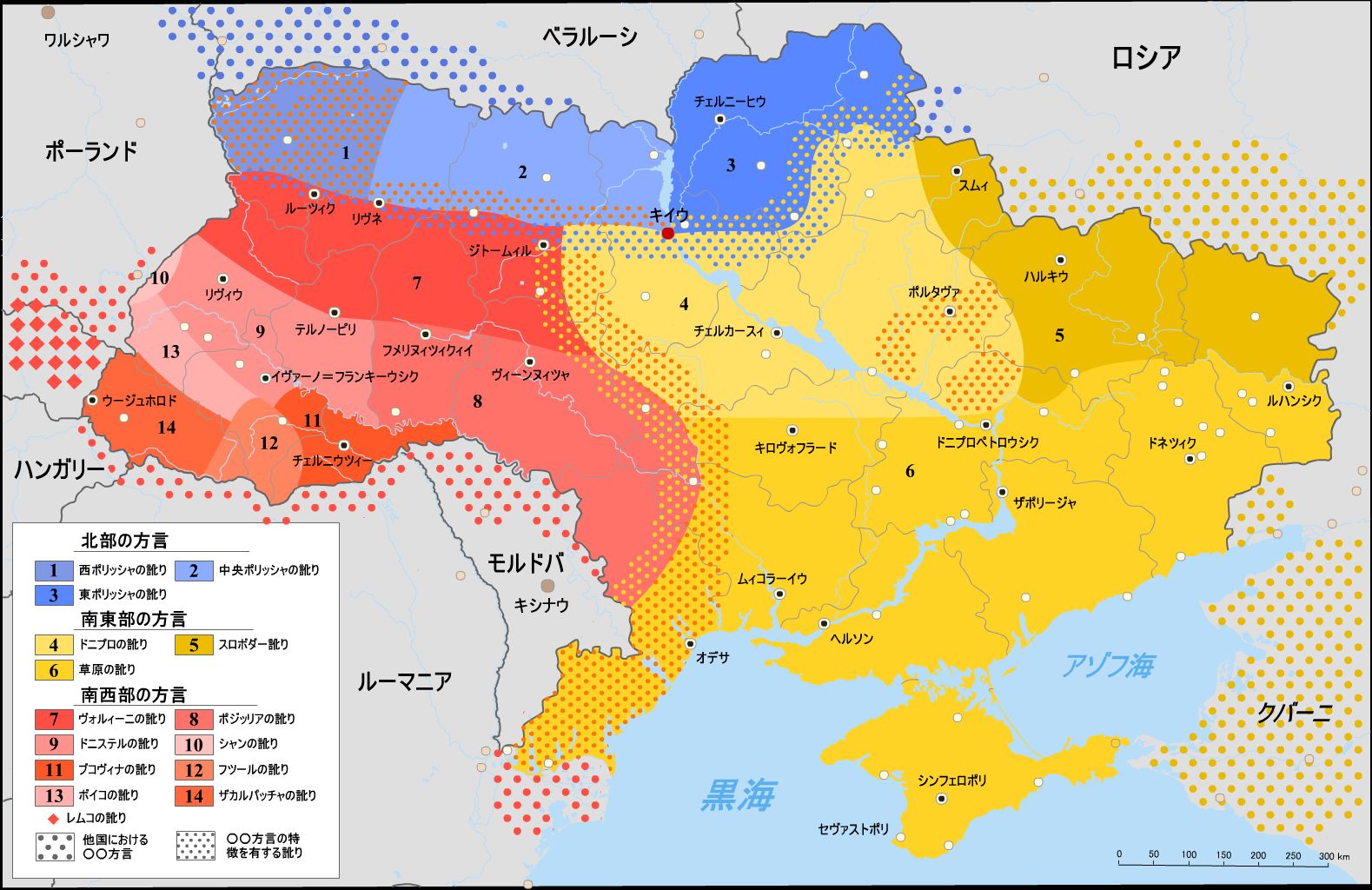

Within Ukraine’s diverse landscape, several other distinct ethnic sub-groups enrich its cultural mosaic, particularly in western Ukraine’s Zakarpattia and Halychyna regions. Among the most recognized are the Hutsuls, known for their unique traditions in the Carpathian mountains, along with the Volhynians, Boykos, and Lemkos, often referred to as Carpatho-Rusyns. Each of these groups boasts particular areas of settlement, distinctive dialects, traditional dress, and cherished folk traditions, adding vibrant threads to the larger Ukrainian cultural tapestry.

Ukraine’s history, much like its geography, has been undeniably turbulent, a narrative of enduring struggles and remarkable resilience. It was in the 9th century that Varangians from Scandinavia arrived, laying the foundational groundwork for the Kievan Rus’ state by conquering proto-Slavic tribes across what is now Ukraine, Belarus, and western Russia. The ancestors of the Ukrainian nation, such as the Polianians, played a pivotal role in the development and cultural flourishing of this early state.

However, the internecine wars among Rus’ princes following the death of Yaroslav the Wise led to political fragmentation, leaving Kievan Rus’ vulnerable. The devastating Mongol invasion in 1236 and 1240 finally brought about the collapse of this foundational state. Yet, the spirit of Ukrainian statehood persisted through entities like the Kingdom of Ruthenia, which flourished from 1199 to 1349, and later, the iconic Cossack Hetmanate.

The Cossacks of Zaporizhzhia, from the late 15th century, exerted significant control over the lower bends of the Dnieper River, strategically positioned between Russia, Poland, and the Crimean Tatars, with their formidable fortified capital, Zaporozhian Sich. Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky stands as a colossal figure in this era, a brilliant military leader whose crowning achievement was the formation of the Cossack Hetmanate state of the Zaporozhian Host (1648–1782), a period of profound national revolution.

Tragically, the late 17th century ushered in a period known as the Ruin, characterized by the disintegration of Ukrainian statehood and a general decline, seeing Ukraine divided along the Dnieper River into hostile Left-Bank and Right-Bank factions. Despite this fragmentation, by the end of the 17th century, approximately 4 million Ukrainians lived, embodying a resilient populace that would eventually ignite a powerful struggle for an independent state at the close of the First World War.

This struggle culminated in the establishment of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) in the central Ukrainian territories, formerly part of the Russian Empire. The Central Rada, led by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, issued four universals, with the Fourth, dated 22 January 1918, boldly declaring the independence and sovereignty of the UNR. Hrushevsky was subsequently elected president, marking a momentous chapter in Ukraine’s quest for self-determination.

The Soviet period brought its own complex tapestry of challenges and transformations. During the 1920s, under the `Ukrainisation` policy championed by Mykola Skrypnyk, Soviet leadership initially fostered a national renaissance in Ukrainian culture and language, part of a broader policy of `Korenisation`, or indigenization. This brief flowering, however, was tragically overshadowed by one of history’s darkest chapters.

From 1932 to 1933, millions of Ukrainians succumbed to a man-made famine, a horrific event known as the Holodomor, engineered by the Soviet regime. The regime maintained a chilling silence, offering no aid to the victims or survivors. Yet, news of this atrocity eventually reached the West, eliciting strong public responses from Polish-ruled Western Ukraine and the Ukrainian diaspora. Since the 1990s, the independent Ukrainian state, many foreign governments, including the United States, and numerous scholars have recognized the Holodomor as an act of genocide, with scholarly estimates of direct deaths ranging from 2.6 million to 12 million.

World War II further reshaped Ukraine’s destiny. Following the Invasion of Poland in September 1939, German and Soviet forces divided Polish territory, leading to Eastern Galicia and Volhynia, with their significant Ukrainian populations, becoming part of Soviet Ukraine. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, these regions temporarily fell under Nazi control.

Ukrainians played a substantial, albeit often tragic, role in the conflict. Between 4.5 million and 7 million ethnic Ukrainians are estimated to have fought in the ranks of the Soviet Army. Pro-Soviet partisan guerrilla resistance in Ukraine peaked at 500,000 in 1944, with approximately 50% being ethnic Ukrainians. However, the period also saw the controversial actions of the UPA, under Roman Shukhevych, accused of ethnic cleansing and massacres of Polish civilians, a deeply contentious aspect of their history that some Ukrainian academics and diaspora groups are accused of “ignoring, glossing over, or outright denying.

The enduring strength of Ukrainian national consciousness is a testament to its deep roots, surviving concerted efforts to suppress it. The period of struggle for independence from 1917 to 1921 served as a pivotal watershed in shaping this modern identity. Joseph Stalin’s regime, however, initiated a brutal reversal in the late 1920s, employing devastating tactics such as the Holodomor, the deportation of `kulaks`, and the physical annihilation of the nationally conscious intelligentsia to destroy and subdue the Ukrainian nation.

Even after Stalin’s death, the concept of a Russified, multiethnic Soviet people was officially promoted, often relegating non-Russian nations to second-class status. Despite this, numerous Ukrainians achieved prominent roles within the Soviet Union, demonstrating an inherent resilience. The ultimate creation of a sovereign and independent Ukraine in 1991, however, powerfully signaled the failure of the “merging of nations” policy and the undeniable, enduring strength of the Ukrainian national spirit. Today, one unfortunate consequence of these historical acts is the presence of Ukrainophobia, underscoring the vital need to understand and appreciate their journey.

Ukrainian national identity, as understood in Eastern Europe, embraces both objective and subjective criteria. It encompasses individuals whose native language is Ukrainian, regardless of their national consciousness, as well as all who self-identify as Ukrainian, whether or not they speak the language. While attempts to introduce a territorial-political concept of Ukrainian nationality, akin to the Western European model, were unsuccessful until the 1990s, the official declaration of Ukrainian sovereignty on 16 July 1990 proudly affirmed that “citizens of the Republic of all nationalities constitute the people of Ukraine,” highlighting a powerful commitment to unity and inclusivity.

Ukrainian culture, shaped by its unique geographical location, gracefully blends Eastern European influences with a discernible Central European touch, particularly in its western regions. Over centuries, it has absorbed movements from the Byzantine Empire and the Renaissance, creating a distinctive cultural fabric. While a strong Christian culture predominated for many centuries, Ukraine also historically served as a fascinating nexus where Catholic, Orthodox, and Islamic spheres of influence converged, adding to its rich complexity.

At the very core of this culture is the Ukrainian language (`украї́нська мо́ва`), proudly standing as the sole official language of the nation. Belonging to the East Slavic branch of the Slavic languages, it is a direct descendant of the colloquial Old East Slavic language of Kievan Rus’, which first diverged into Ruthenian and Russian. The Ruthenian languages then beautifully evolved into modern-day Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Rusyn, showcasing a shared linguistic heritage. While many Ukrainians are fluent in Russian, the language exhibits a particularly close lexical distance and mutual intelligibility with Belarusian, a truly remarkable linguistic kinship. Historically, efforts at Russification saw the Ukrainian language banned from schools and instruction in the Russian Empire, and oppression continued during the Soviet era, yet the language bravely persisted, especially in the western part of the country, a testament to its resilience.

The spiritual landscape of Ukraine is predominantly shaped by Eastern Orthodoxy, a faith embraced by the vast majority and making Ukrainians the second largest ethno-linguistic group among Eastern Orthodox worldwide. Prince Vladimir’s baptism of his people in the Dnieper River in the 10th century marked the beginning of this long and profound history. Today, Ukrainians cherish their own autocephalous Orthodox Church of Ukraine, led by Metropolitan Epiphanius, which is the most common church in the country.

In the western region of Halychyna, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, an Eastern Rite Catholic Church, also boasts a strong and vibrant membership. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Ukraine has also witnessed a heartening growth in Protestant churches, including Baptists, Evangelicals, and Pentecostals, further diversifying its religious landscape. Ethnic minorities like Crimean Tatars (Islam) and Jews and Karaim (Judaism) contribute to the rich tapestry of faiths, alongside followers of the Seventh-day Adventist Church and Jehovah’s Witnesses, painting a vivid picture of religious pluralism.

Ukrainian cuisine is a delightful reflection of the nation’s tumultuous history, diverse geography, and cherished social customs, making it a truly flavorful experience. Chicken is the most consumed protein, accounting for about half of the meat intake, closely followed by pork and beef. Vegetables such as potatoes, cabbage, mushrooms, and beetroots are widely enjoyed, with pickled vegetables considered a particular delicacy, adding a zesty kick to meals.

A true national treasure is `Salo`, cured pork fat, revered as the national delicacy, symbolizing the hearty and resourceful nature of Ukrainian cooking. Widely used herbs like dill, parsley, basil, coriander, and chives infuse dishes with aromatic freshness. Ukraine is famously known as the “Breadbasket of Europe,” and its abundant grain and cereal resources, especially rye and wheat, are fundamental to its cuisine, forming the basis for an incredible array of breads. The country’s `Chernozem`, its highly fertile black soil, is renowned for producing some of the world’s most flavorful crops, truly a gift from nature.

Traditional Ukrainian dishes are comfort food personified, beloved for their rich flavors and comforting warmth. `Varenyky` (dumplings) are a national obsession, alongside `nalysnyky` (crêpes), `kapusnyak` (cabbage soup), `nudli` (dumpling stew), the iconic `borscht` (sour soup), and `holubtsi` (cabbage rolls), each a masterpiece of culinary heritage. Traditional baked goods like the elaborately decorated `korovai` and the celebratory `paska` (Easter bread) are central to festive occasions, embodying deeply rooted cultural significance. And of course, one cannot forget the internationally renowned Chicken Kiev and the exquisite Kyiv cake, both delicious testaments to Ukrainian culinary artistry. Popular drinks include the refreshing `uzvar` (kompot), `ryazhanka`, and the potent `horilka`, with liquor being the most consumed alcoholic beverage, though consumption has seen a stark decrease.

Ukrainian music is a soulful symphony, weaving together diverse external cultural influences with a powerful, indigenous Slavic and Christian uniqueness that has resonated across many neighboring nations. Its folk oral literature, poetry, and songs, especially the poignant `dumas`, are among the most distinctive ethnocultural features of the Ukrainian people, speaking volumes about their artistic spirit. Traditional Ukrainian music is often recognized by its somewhat melancholy tone, conveying a depth of emotion that is truly captivating.

This rich musical heritage began to gain recognition beyond Ukraine as early as the 15th century, with Ukrainian musicians gracing royal courts in Poland and later Russia. Ukraine proudly stands as the rarely acknowledged musical heartland of the former Russian Empire, having established its first professional music academy in the mid-18th century, which nurtured countless early musicians and composers, leaving an indelible mark on the global stage. Names like Dmitry Bortniansky, Sergei Prokofiev, and Myroslav Skoryk, among many others, testify to Ukraine’s profound musical legacy.

Ukrainian dance is a dazzling display of energy and artistry, captivating audiences worldwide. While its traditional folk dances are rooted in deep historical forms, today they are primarily represented by what ethnographers call “Ukrainian Folk-Stage Dances.” These are highly stylized, choreographed representations of traditional movements, transforming authentic folk steps into breathtaking concert performances. This dynamic art form has so deeply permeated Ukrainian culture that it has become a universally recognized and appreciated symbol, often described as energetic, fast-paced, and wonderfully entertaining, standing proudly alongside traditional Easter eggs (pysanky) as a hallmark of Ukrainian heritage.

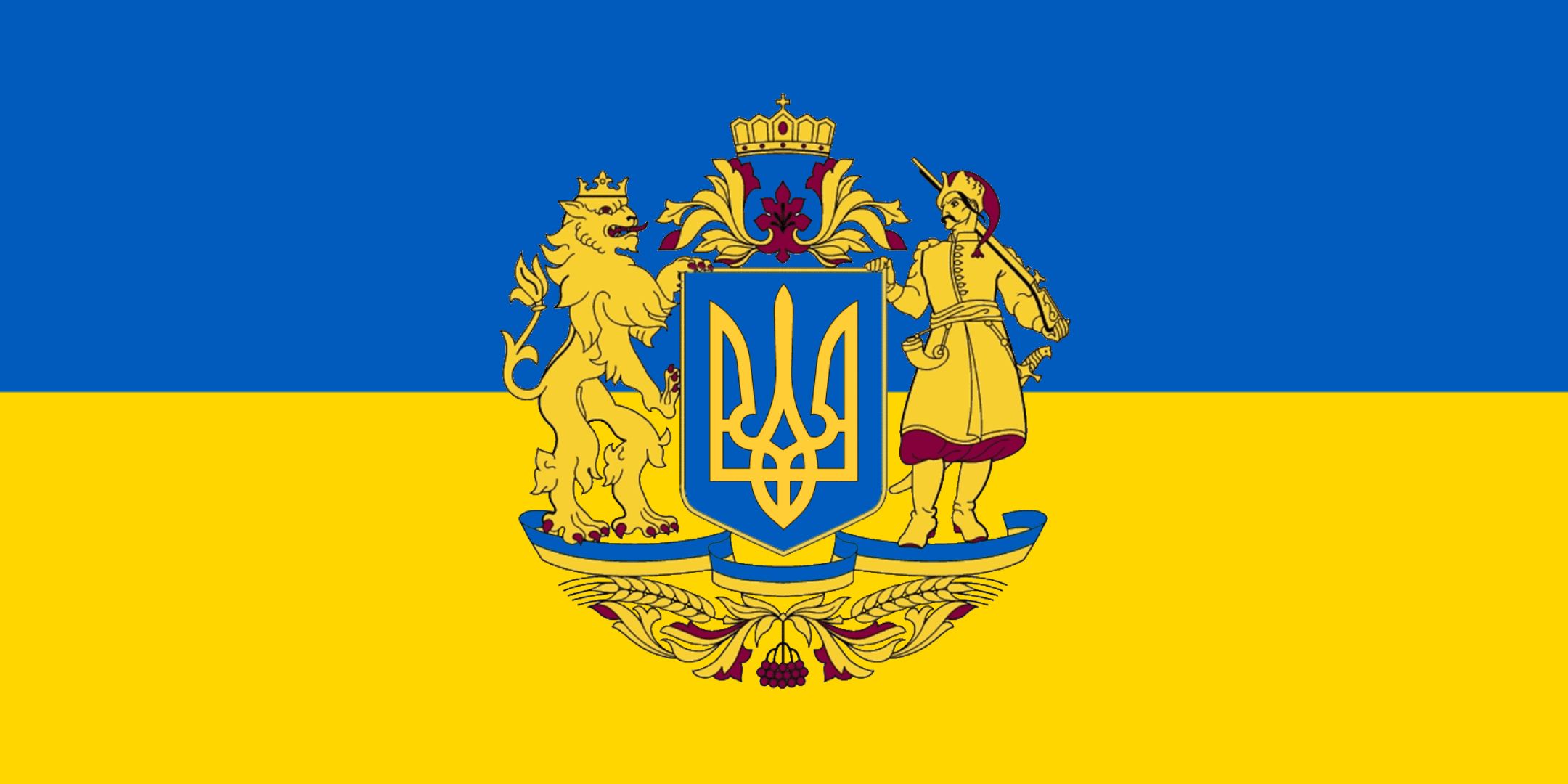

The national symbols of Ukraine are imbued with profound meaning, representing the nation’s enduring connection to its land and history. The national flag of Ukraine is a striking blue and yellow bicolour rectangle, with fields of the same form and equal size. These vibrant colors beautifully symbolize a blue sky stretching endlessly above golden fields of wheat, an homage to Ukraine’s agricultural bounty and its serene natural beauty. This flag, designed for the Supreme Ruthenian Council in 1848, draws its colors directly from the ancient coat-of-arms of the Kingdom of Ruthenia, linking the modern nation to its deep historical roots.

Complementing the flag, the Coat of Arms of Ukraine features the same significant colors: a blue shield proudly bearing a yellow trident. This powerful symbol, the trident, represents the ancient East Slavic tribes that once thrived in Ukraine, later adopted by influential Ruthenian and Kievan Rus rulers. It stands as a timeless emblem of sovereignty, strength, and continuity, echoing the very essence of Ukrainian identity and its remarkable journey through time.

To truly grasp the essence of Ukraine is to appreciate its enduring resilience, its rich cultural tapestry, and the vibrant spirit of its people. From the nuanced evolution of their ethnonym to their widespread global diaspora, from the profound depths of their genetic heritage to the intricate layers of their history, Ukrainians have forged a unique identity. Their language, their unwavering faith, their delicious cuisine, their expressive music and dance, and their evocative symbols all speak volumes of a nation that has not only survived tumultuous times but thrived, maintaining a profound sense of self and community against all odds. It is a story not just of struggle, but of an indomitable will to flourish, a testament to the beautiful, multifaceted soul of Ukraine, continually inspiring awe and admiration. The journey through Ukrainian heritage is one of discovery, warmth, and an undeniable celebration of the human spirit.