When we envision the Middle Ages, our minds often conjure images of knights, castles, and vast, untamed landscapes. Yet, amidst this grand tapestry of human history, a captivating story unfolds—one starring our most ancient animal companions: dogs. Far from being mere background figures, these remarkable creatures played an integral, multifaceted role in medieval life, intertwining with human existence in ways that are both surprisingly familiar and uniquely historical.

Indeed, the modern concept of a ‘pet,’ a companion kept solely for affection and leisure, wasn’t formally codified until the 16th century. However, to assume a lack of emotional bond between medieval people and their dogs would be a profound oversight. As we journey through the rich tapestry of medieval life, from bustling town squares to serene monastic cloisters, we discover that dogs were not only essential working animals but also cherished companions, status symbols, and even figures of spiritual significance, deeply embedded in the cultural fabric of the era.

This in-depth exploration will illuminate the often-overlooked yet profoundly significant presence of dogs during the Middle Ages. We’ll uncover their diverse vocations, their elevated status among the nobility, the tender care they received, and their curious place even within the hallowed halls of the Church. Prepare to be enchanted by the tales of medieval canines, whose stories offer a unique window into the values, beliefs, and daily realities of a bygone world.

1. **The Indispensable Workers: Diverse Roles of Medieval Dogs**In the grand theatre of medieval life, most dogs were not simply ‘pets’ in the contemporary sense; they were indispensable workers, each assigned a specific role vital to human survival and societal function. The 16th-century English physician and scholar John Caius, in his insightful book *De Canibus*, meticulously classified dogs primarily by their function within human society, highlighting a world where canine labor was the norm.

In the grand theatre of medieval life, most dogs were not simply ‘pets’ in the contemporary sense; they were indispensable workers, each assigned a specific role vital to human survival and societal function. The 16th-century English physician and scholar John Caius, in his insightful book *De Canibus*, meticulously classified dogs primarily by their function within human society, highlighting a world where canine labor was the norm.

From the highest echelons to the humblest strata, dogs provided essential services. Specialised hunting dogs, such as the swiftly moving greyhounds and the keen-nosed bloodhounds, were crucial for pursuing prey across diverse terrains. But even the ‘mungrells’ or mixed-breeds, often found at the bottom of Caius’s canine social ladder, were defined by their labor. They might perform as street entertainers, bringing joy to common folk, or endure the strenuous life of a turnspit, running on wheels to rotate roasting meat in busy kitchens.

The context further reveals a broader spectrum of working roles across medieval Europe. Dogs served as guard dogs, protecting homes, goods, and livestock for all levels of society. They were ‘lymers,’ skilled in sniffing out game, and ‘raches’ who ran down quarry during the hunt. Smaller hunting hounds were known as ‘kennets,’ while other canines labored as ‘water-drawers,’ turning well-wheels to raise buckets, and even as ‘messengers,’ carrying letters tucked into their collars between homes and businesses. This extensive list of occupations underscores the pervasive and practical utility of dogs in a society reliant on animal power and keen senses.

Herding dogs, such as sheepdogs and cattle dogs, were also essential for managing livestock, trained to respond to intricate commands. John Bromyard, a 14th-century English clergyman, aptly described them: “The dog is a faithful beast, and follows his master, and keeps and guards his sheep, and barks against wolves and thieves, and is obedient to his lord‘s commandments.” Terriers, too, played their part, hunting small game and controlling vermin. Indeed, the working dog was a cornerstone of medieval communities, a testament to their intelligence, training, and tireless dedication.

2. **Noble Hounds and Royal Hunts: Dogs as Elite Status Symbols**Beyond their utilitarian functions, dogs, particularly certain breeds, ascended to a prominent position as potent signifiers of elite social rank within medieval aristocratic culture. As hunting transitioned from a necessity to an aristocratic pastime, the place of dogs in society underwent a significant transformation. They were no longer just tools but symbols, welcomed inside noble homes and particularly cherished by women of the upper classes.

Beyond their utilitarian functions, dogs, particularly certain breeds, ascended to a prominent position as potent signifiers of elite social rank within medieval aristocratic culture. As hunting transitioned from a necessity to an aristocratic pastime, the place of dogs in society underwent a significant transformation. They were no longer just tools but symbols, welcomed inside noble homes and particularly cherished by women of the upper classes.

The practice of dog breeding, potentially originating from Roman times, flourished among the aristocracy, ensuring a lineage of highly prized animals. Ancestors of many modern dog breeds, including greyhounds, spaniels, poodles, and mastiffs, are discernible in medieval sources. Greyhounds, a term encompassing various sight hounds, were exceptionally esteemed and considered fitting gifts for princes, highlighting their immense value and the prestige associated with their ownership.

Specialized hunting dogs, such as mastiffs and wolfhounds, were also kept for protection, valued for their imposing size, strength, and ferocity. The 13th-century English writer Walter of Henley advised in his treatise on estate management: “A mastiff is a good dog to keep in your courtyard, for he will allow no one to enter unless he knows them well, and he will bark at strangers and bite them if necessary.” This dual role of guardian and hunting partner solidified their place at the apex of the canine hierarchy in aristocratic households.

John Caius, in his ranking, placed these “delicate, neate, and pretty” indoor dogs below hunting dogs but notably above common mongrels, precisely because of their association with the noble classes. This meticulous classification underscores how deeply integrated dogs were into the social hierarchy, reflecting not only their physical attributes but also the social standing of their human companions. The presence of these refined canines in noble households was a clear public declaration of status and a testament to a life of privilege.

3. **Lapdogs: The Pampered Companions of Medieval Society**Among the nobility, especially women, lapdogs emerged as cherished companions, signifying a shift towards a more intimate human-canine bond that transcended mere utility. These “delicate, neate, and pretty” indoor dogs, often of smaller breeds, were ideally suited for indoor pursuits, becoming a fixture in aristocratic homes by the 13th century, a fashion that resonated with the ancient Roman practice of keeping such pets.

Among the nobility, especially women, lapdogs emerged as cherished companions, signifying a shift towards a more intimate human-canine bond that transcended mere utility. These “delicate, neate, and pretty” indoor dogs, often of smaller breeds, were ideally suited for indoor pursuits, becoming a fixture in aristocratic homes by the 13th century, a fashion that resonated with the ancient Roman practice of keeping such pets.

These pampered pooches were more than just charming presences; they were, in many ways, living accessories, carried around and cradled by noble and wealthy women. The allure of smaller dogs was undeniable, with Caius noting that “the smaller they be, the more pleasure they provoke.” This affection was often translated into tangible material investment, as medieval dog owners with means adorned their companions with a variety of accessories. Leashes, coats, and cushions made from fine materials were not uncommon, reflecting the aristocratic culture of *vivre noblement*—the art of noble living—where luxury commodities publicly demonstrated one’s elevated status.

However, this growing fondness for lapdogs was not universally celebrated. Some critics viewed these pampered companions with disdain, associating them with female idleness and vice. The 16th-century English chronicler Raphael Holinshed voiced this sentiment, complaining that lapdogs were “[Lapdogs are] instruments of folly to play and dally withal, in trifling away the treasure of time, to withdraw [women‘s] minds from more commendable exercises.” Hans Memling’s painting *Allegory of Vanity* (c. 1485) visually reinforces this gendered stereotype, where toy dogs are linked to notions of triviality.

Despite these criticisms, the appeal of lapdogs persisted, remaining an enduring fixture of aristocratic homes. Their presence, whether seen as a symbol of luxury or a distraction, undeniably highlighted a developing emotional connection between humans and dogs, particularly among those with the leisure and resources to indulge in such companionship. This relationship laid the groundwork for the modern concept of pets, showcasing an affection that transcended practical necessity.

4. **Care and Craftsmanship: The Grooming and Housing of Medieval Canines**The care bestowed upon medieval dogs, particularly those belonging to the noble classes, reveals a level of meticulous attention that parallels modern pet ownership. Whether working tirelessly in the hunt or reclining elegantly in a lady’s lap, these animals were often afforded considerable provisions, reflecting their value and the affection of their owners. This dedicated approach to canine well-being underscores a relationship far more complex than simple utility.

The care bestowed upon medieval dogs, particularly those belonging to the noble classes, reveals a level of meticulous attention that parallels modern pet ownership. Whether working tirelessly in the hunt or reclining elegantly in a lady’s lap, these animals were often afforded considerable provisions, reflecting their value and the affection of their owners. This dedicated approach to canine well-being underscores a relationship far more complex than simple utility.

Aristocratic households often employed ‘dog-boys,’ dedicated servants whose sole responsibility was the welfare of the hounds. These individuals were with the dogs at all times, ensuring their needs were met. Kennels, specially constructed for these valuable animals, were not merely rudimentary enclosures. According to the 15th-century English hunting manual *The Master of Game*, a good kennel required thoughtful design: it should be “well-roofed and walled with planks, and the ground should be paved to keep it dry… and in front of the kennel should be a grass plot, for the hounds to play and run about” (MS Bodley 546, c. 1406-1413). Such structures were also recommended to be cleaned daily and often included fires to keep the dogs warm, demonstrating an awareness of their comfort and health.

Meticulous care extended to the working dogs as well, recognizing that their performance was directly linked to their well-being. A lavish 15th-century copy of Gaston Phébus’s *Livre de la Chasse* (Book of Hunting) features a miniature depicting kennel attendants diligently examining dogs’ teeth, eyes, and ears, while another lovingly bathes the paws of a very good boy. This imagery highlights the comprehensive approach to canine health, acknowledging that even the most robust working animals required careful attention and hygiene to perform at their best.

Beyond their physical needs, the material investment in dogs was considerable, especially for lapdogs. These companions of the elite were kitted out with an array of accessories, including leashes, coats, and cushions crafted from fine materials. This lavish accessorizing was a central element of the aristocratic culture of *vivre noblement*, where the deliberate consumption of luxury goods publicly affirmed one’s high status. Such practices, while outwardly demonstrating social standing, also speak to an underlying indulgence and affection, showing that medieval dog owners were no less devoted than their modern counterparts.

5. **A Contested Presence: Dogs Within the Medieval Church**Despite formal disapproval from the highest echelons, dogs maintained a surprisingly persistent and sometimes contentious presence within the medieval Church. This intriguing paradox reveals much about the pervasive role of canines in daily life and the challenges ecclesiastical authorities faced in regulating the personal affections of their clergy and congregations.

Despite formal disapproval from the highest echelons, dogs maintained a surprisingly persistent and sometimes contentious presence within the medieval Church. This intriguing paradox reveals much about the pervasive role of canines in daily life and the challenges ecclesiastical authorities faced in regulating the personal affections of their clergy and congregations.

While the Church formally expressed disapproval of pets, clerics themselves often owned dogs, directly flouting the very rules intended to maintain an austere and focused spiritual life. Like women of the nobility, clerics’ dogs were typically lapdogs, perfectly suited to their indoor pursuits within monasteries and rectories. These small companions offered solace and companionship, seemingly irresistible even to those vowed to lives of contemplation and detachment.

The canine presence wasn’t limited to the clergy; lay people commonly brought their dogs to church, an act that frequently drew the ire of church leaders. The 14th-century Archbishop of York, for instance, irritably observed that such practices “impede the service and hinder the devotion of the nuns.” This highlights a recurring struggle between popular customs and ecclesiastical decrees, where the strong bond between humans and their dogs often trumped formal regulations, suggesting that the comfort these animals provided was deeply valued.

The context also draws a fascinating connection between dogs and Christian ideals. While some biblical passages characterized dogs as “filthy scavengers,” implying negative connotations, other narratives presented them in a highly positive light. The story of St. Roch from *The Golden Legend* tells of a dog bringing bread to a starving saint and healing his wounds with licks. A devoted dog became one of Roch’s saintly attributes, showcasing the animal’s capacity for selfless service and divine association, effectively redeeming the canine image within religious narratives despite institutional reservations.

Even in death, dogs found a place in religious iconography, albeit subtly. While the belled collar on the long-eared dog at the feet of Archbishop William Courtenay’s effigy (d. 1396) in Canterbury Cathedral was a popular convention for lapdogs, it’s tempting to wonder if it represented an actual pet. In clerical tombs, dogs could also symbolise the faith of the deceased, further cementing their multifaceted significance within the spiritual landscape of the Middle Ages, defying simple categorization and reflecting a complex interplay of affection, practicality, and symbolism.

6. **The Enduring Virtue of Canine Loyalty in Medieval Thought**In the intricate tapestry of medieval life, dogs were celebrated not merely for their practical roles, but profoundly for their unwavering loyalty—a quality that deeply resonated with human values of devotion and fidelity. Medieval scholars and everyday folk alike recognized a unique intelligence and understanding in canines, distinguishing them from other animals.

In the intricate tapestry of medieval life, dogs were celebrated not merely for their practical roles, but profoundly for their unwavering loyalty—a quality that deeply resonated with human values of devotion and fidelity. Medieval scholars and everyday folk alike recognized a unique intelligence and understanding in canines, distinguishing them from other animals.

The *Aberdeen Bestiary* (c. 1200) eloquently stated, “No creature is more intelligent than the dog, for dogs have more understanding than other animals; they alone recognise their names and love their masters.” This sentiment was echoed by Gaston, Comte de Foix, a 14th-century hunter, who praised his hounds’ comprehension, noting they understood him “better than any man of my household,” underscoring their exceptional ability to learn and obey.

Tales of canine fidelity, traceable to classical texts like Pliny the Elder’s *Natural History*, flourished in medieval bestiaries. These moralizing compendiums included stories such as the legendary King Garamantes, tracked and rescued by his faithful dogs after capture. Another recounted a dog bravely identifying and attacking its master’s murderer, demonstrating a justice found through canine instinct. These narratives, whether historical or allegorical, powerfully reinforced the cultural perception of dogs as paragons of loyalty and steadfast protectors.

7. **Law and Order: Regulating Medieval Dogs**The pervasive integration of dogs into medieval society necessitated structured legal frameworks to manage their ownership and conduct. These regulations offer a compelling insight into the era’s focus on public safety, resource allocation, and the maintenance of social order, reflecting a sophisticated approach to human-animal cohabitation.

The pervasive integration of dogs into medieval society necessitated structured legal frameworks to manage their ownership and conduct. These regulations offer a compelling insight into the era’s focus on public safety, resource allocation, and the maintenance of social order, reflecting a sophisticated approach to human-animal cohabitation.

Early legal measures, such as the *Lex Romana Burgundionum* (c. 515 CE), mandated that dogs be leashed and collared, holding owners fully responsible for any damage caused by untethered animals. This foresightful legislation aimed to prevent harm and ensure accountability, a principle remarkably akin to modern pet ownership laws.

The aristocratic passion for hunting also heavily influenced canine legislation. The 6th-century Forest Laws, among Europe’s earliest game laws, restricted commoners from hunting in royal forests while granting nobility unimpeded passage with their hounds across any land. This class-based application of the law underscored the elite status of hunting dogs.

The value of specific breeds, especially greyhounds, within this noble pursuit led to severe protections. King Hywel Dda of Wales made killing a greyhound a capital crime, while King Canute later made their ownership exclusive to the nobility. Canute also intensified Forest Laws, mandating the hobbling of other dog breeds near royal hunting grounds to prevent interference. Such stringent regulations, continued by William the Conqueror, highlight the crucial, yet often regulated, role of dogs in medieval society.

8. **Canines in Canvas and Chronicle: Dogs in Medieval Art and Literature**The significant role dogs played in medieval life was vividly captured across its art and literature, where they appeared not merely as background figures but as symbols and active participants in human narratives. These diverse depictions offer a unique window into medieval perceptions of canine companions.

The significant role dogs played in medieval life was vividly captured across its art and literature, where they appeared not merely as background figures but as symbols and active participants in human narratives. These diverse depictions offer a unique window into medieval perceptions of canine companions.

The Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1070 CE) notably features dogs with Harold Godwinson, depicted with slim leather collars, hinting at their established presence in both daily life and significant historical events. Centuries later, the Unicorn Tapestries (c. 1495-1505 CE) prominently display greyhounds in six of its seven works, adorned with broad, inscribed collars, signifying their integral, identifiable role in aristocratic hunts and reflecting the status of their owners.

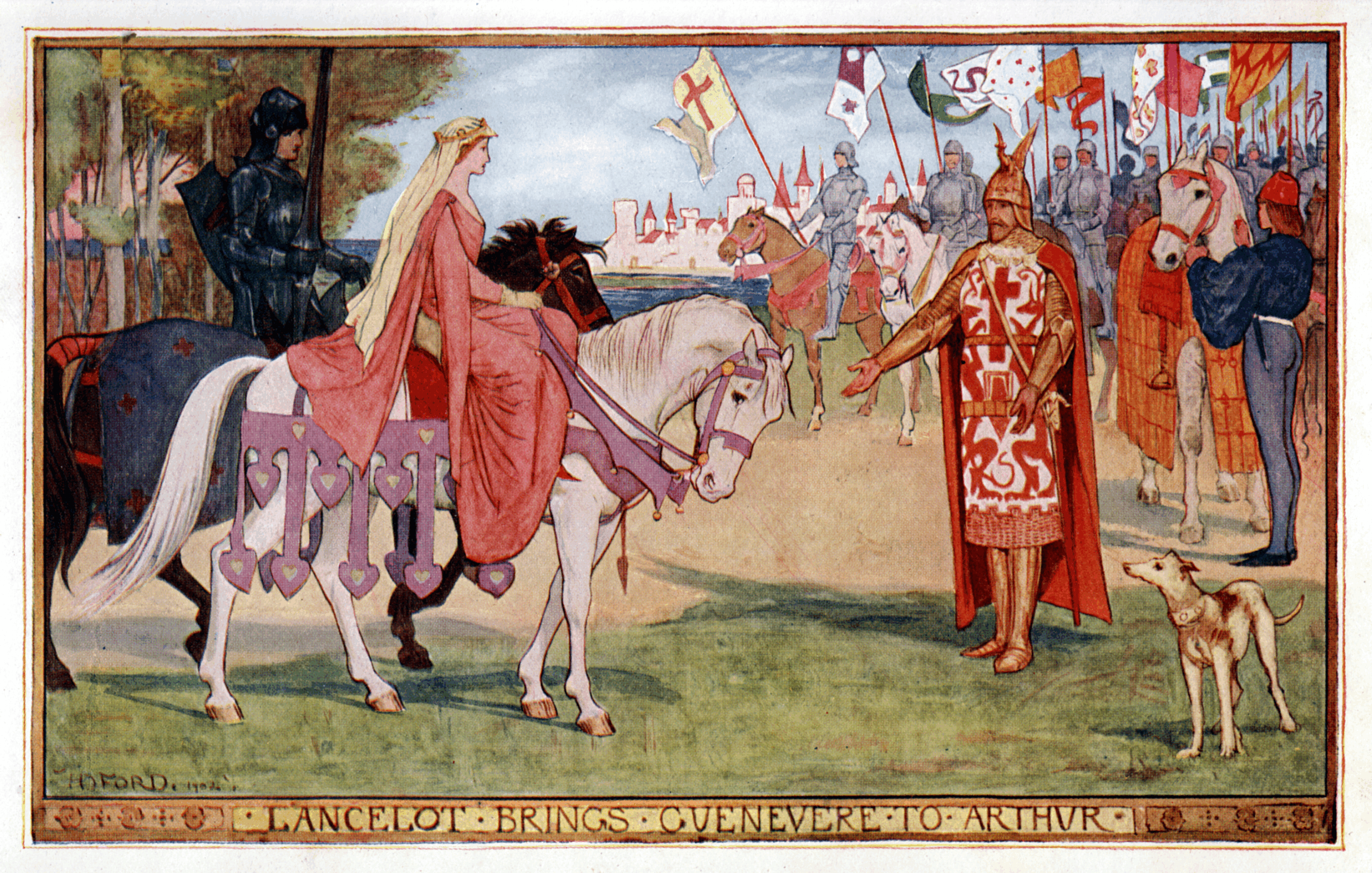

In medieval literature, dogs frequently featured, particularly in courtly love romances. Anonymous tales like *The Chatelaine de Vergy* (13th century) describe a small, well-trained dog acting as a discreet messenger in a clandestine affair, underscoring canine intelligence and trustworthiness. Gottfried von Strassburg’s *Tristan* (c. 1210 CE) introduces Petitcreiu, a magical lapdog whose sorrow-banishing bell becomes central to Isolt’s emotional choice between magical solace and true grief.

Furthermore, dogs often appeared in funerary art. On tomb monuments, dogs typically symbolized the fidelity of a wife to her husband, or in clerical tombs, the faith of the deceased, as exemplified by Archbishop William Courtenay’s effigy with its belled dog. These artistic and literary inclusions firmly establish the dog as a versatile and meaningful presence, reflecting both practical utility and deep symbolic resonance in the medieval imagination.

9. **Legends of Fidelity and Sacrifice: Iconic Dog Tales**Across the Middle Ages, the unwavering fidelity and self-sacrificing courage of dogs inspired a rich tapestry of legends and folklore. These tales elevated dogs to near-mythical status, celebrating their cherished virtues and underscoring the profound human-animal bond through narratives of loyalty and protection.

Across the Middle Ages, the unwavering fidelity and self-sacrificing courage of dogs inspired a rich tapestry of legends and folklore. These tales elevated dogs to near-mythical status, celebrating their cherished virtues and underscoring the profound human-animal bond through narratives of loyalty and protection.

*The Golden Legend*, a popular 13th-century collection, tells of St. Roch, afflicted with plague. A devoted dog brought him bread daily and licked his wounds, healing him. This selfless act enshrined the dog as one of St. Roch’s attributes, transforming the animal into a symbol of divine comfort and unwavering support.

The legendary King Arthur’s companion, Cavall, left his pawprint in a Welsh stone during a hunt. Arthur honored his loyal dog with a cairn, and legend states any removed stone would miraculously return, symbolizing a dog’s eternal devotion to its master.

Perhaps the most poignant tale is *The Legend of Gelert*, from 13th-century Wales. Llewelyn the Great mistakenly killed his loyal dog, Gelert, believing it had harmed his infant son, only to discover Gelert had bravely slain a wolf. Overwhelmed by grief, Llewelyn reportedly never smiled again. This story, though often presented as fact, powerfully illustrates the anguish of mistaken judgment and the profound sacrifice of a loyal animal. A similar, possibly earlier, narrative forms the basis of the Cult of Saint Guinefort, a greyhound mistakenly killed after saving an infant from a snake. Its subsequent veneration for healing highlights the deep respect medieval people held for these faithful, legendary canines.

10. **Collar Codes: The Fashion and Function of Medieval Dog Accessories**The medieval appreciation for dogs was tangibly expressed through their accessories, particularly collars, which served as both functional restraints and significant statements of status, wealth, and utility. These varied accoutrements offer a unique insight into the multifaceted roles dogs occupied in society.

The medieval appreciation for dogs was tangibly expressed through their accessories, particularly collars, which served as both functional restraints and significant statements of status, wealth, and utility. These varied accoutrements offer a unique insight into the multifaceted roles dogs occupied in society.

Early medieval collars evolved from practical necessity to intricate craftsmanship. The *Lex Romana Burgundionum* (c. 515 CE) mandated basic collars, while archaeological finds from Valsgarde, Sweden, reveal leather bands adorned with metal squares. By the 12th century, an elaborate bronze collar from Waterford, Ireland, showcased intricate web patterns, demonstrating a surprising level of artistry applied to canine wear.

In hunting, collars were crucial. The Bayeux Tapestry depicts dogs with slim leather collars, hinting at their functional attire during the hunt. The Unicorn Tapestries (c. 1495-1505 CE) feature greyhounds wearing broad, inscribed collars with letters or floral designs. These elaborate pieces likely indicated ownership and status, transforming the dog’s accessory into a symbol of familial identity.

For the pampered lapdogs of the nobility, accessories transcended utility to become expressions of luxury. Aristocratic owners lavished their companions with fine leashes, coats, and cushions, reflecting the *vivre noblement* culture where material investment publicly affirmed high status. The belled collar, a popular convention in contemporary iconography, further exemplifies this blend of charm and aristocratic display, underscoring the dog’s ornamental and cherished role.

11. **A Tapestry of Perceptions: Diverse Cultural and Regional Attitudes**The human-dog relationship in the Middle Ages, while generally marked by practicality and loyalty, was far from uniform. Across medieval Europe and beyond, attitudes towards canines were shaped by a rich interplay of cultural, religious, and pragmatic considerations, revealing both universal appeals and context-specific roles.

The human-dog relationship in the Middle Ages, while generally marked by practicality and loyalty, was far from uniform. Across medieval Europe and beyond, attitudes towards canines were shaped by a rich interplay of cultural, religious, and pragmatic considerations, revealing both universal appeals and context-specific roles.

In stark contrast to Western Europe, the Islamic world typically regarded dogs as unclean, often prohibiting their presence in homes or sacred spaces. The 14th-century Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta expressed astonishment at European dogs freely entering churches, highlighting a significant cultural divergence driven by religious beliefs.

In Scandinavia, dogs played a complex role in Viking culture, serving as vital hunting companions and, at times, sacrificial animals. The 13th-century *Egil’s Saga* describes a warrior buried with his dog, reflecting a belief in canine companionship extending into the afterlife—a profound spiritual connection.

Medieval Russia also highly valued dogs for work and companionship, intertwining them with folklore. The 12th-century *Russian Primary Chronicle* recounts Prince Oleg of Novgorod’s death, tragically caused by a snake from his favorite hunting dog’s skull. This poignant tale speaks to the deep emotional bond and significance dogs held in daily life.

Despite regional variations, a fascinating consistency emerged across diverse civilizations: dogs almost uniformly served as guardians, hunters, and companions. While some cultures, like parts of China and Mesoamerica, also bred dogs as a food source, the core virtues of protection and companionship remained globally recognized. This continuity underscores the dog’s unique and enduring position in human society, a testament to a bond that transcends geography and time.

The story of humanity is intrinsically linked with that of the dog. Far from being relegated to the periphery, these intelligent, loyal, and endlessly adaptable creatures were central to the medieval experience, mirroring human ambitions, fears, and affections. Whether silently guarding a lord’s castle, vigorously pursuing game across sprawling landscapes, or quietly comforting a noblewoman, dogs traversed the social strata and cultural landscapes of the Middle Ages with an enduring presence. They were workers, symbols, and cherished companions, shaping daily lives and influencing legal codes, art, and literature in ways that continue to illuminate our understanding of this fascinating era. The medieval dog, in its diverse forms and functions, offers a powerful testament to an ancient bond, a shared history, and the timeless loyalty that continues to define our relationship with our most faithful friends.