In the vast and intricate tapestry of biblical literature, certain texts stand out not merely for their spiritual import, but for their profound historical and scholarly significance. Among these, the Gospel of Mark occupies a uniquely compelling position, often regarded as the earliest and most direct account of Jesus’ ministry. It is a document whose concise narrative, brisk pacing, and powerful imagery have captivated readers and scholars for millennia, offering a lens into the nascent Christian movement.

To approach the Gospel of Mark is to engage with a work of antiquity that, much like a meticulously crafted timepiece, reveals layers of sophisticated engineering and purposeful design upon closer inspection. Our journey into this seminal text will adopt a discerning perspective, analyzing its components with the detail and authority typically reserved for the world’s most aspirational artifacts. We aim to uncover the robust scholarly consensus that frames its understanding, as well as the intricate debates that continue to define its study.

This first section will meticulously dissect the compositional genesis of Mark, delving into its widely accepted status as the earliest gospel and its implications for subsequent New Testament writings. We will examine the contentious question of its authorship, trace the historical context that likely shaped its creation, and explore its identification as an ancient biography. Furthermore, we will pinpoint a crucial structural pivot that redefines the narrative’s trajectory, offering a comprehensive and insightful foundation for appreciating this remarkable ancient text.

1. **The Scholarly Consensus: Marcan Priority and the Two-Source Hypothesis**Modern biblical scholarship, with remarkable unanimity, largely accepts the hypothesis of Marcan priority, positioning the Gospel of Mark as the foundational text among the synoptic gospels. This view posits that the authors of Matthew and Luke drew significantly from Mark as a primary source for their own narratives. It is a cornerstone agreement, shaping much of our contemporary understanding of the New Testament’s literary genesis and interrelationships.

The widespread acceptance of Marcan priority is often paired with the ‘two-source hypothesis.’ This scholarly model suggests that Matthew and Luke utilized not only Mark but also another hypothetical document, traditionally referred to as the ‘Q source,’ primarily containing sayings of Jesus. This intricate interplay between sources reveals a sophisticated process of gospel composition, where earlier traditions and narratives were consciously adapted and expanded upon by later evangelists.

The implications of Mark serving as the earliest gospel are profound. It suggests that Mark presents an unadorned, perhaps even raw, account of Jesus’ life and ministry, prior to the theological and narrative expansions found in Matthew and Luke. This perceived originality has historically led many scholars to view Mark as the most reliable gospel for reconstructing facts about the historical Jesus, offering a direct conduit to the earliest layers of Christian tradition.

However, this long-held conceit, while influential, has not been without its challenges. Recent scholarship, as the context indicates, has begun to question Mark’s absolute reliability, with figures like Michael Patrick Barber and Dale Allison arguing that Matthew’s overall portrait may present a more historically plausible picture in certain regards. Nonetheless, the framework of Marcan priority remains a dominant paradigm, underpinning most textual analyses and critical interpretations of the synoptic tradition.

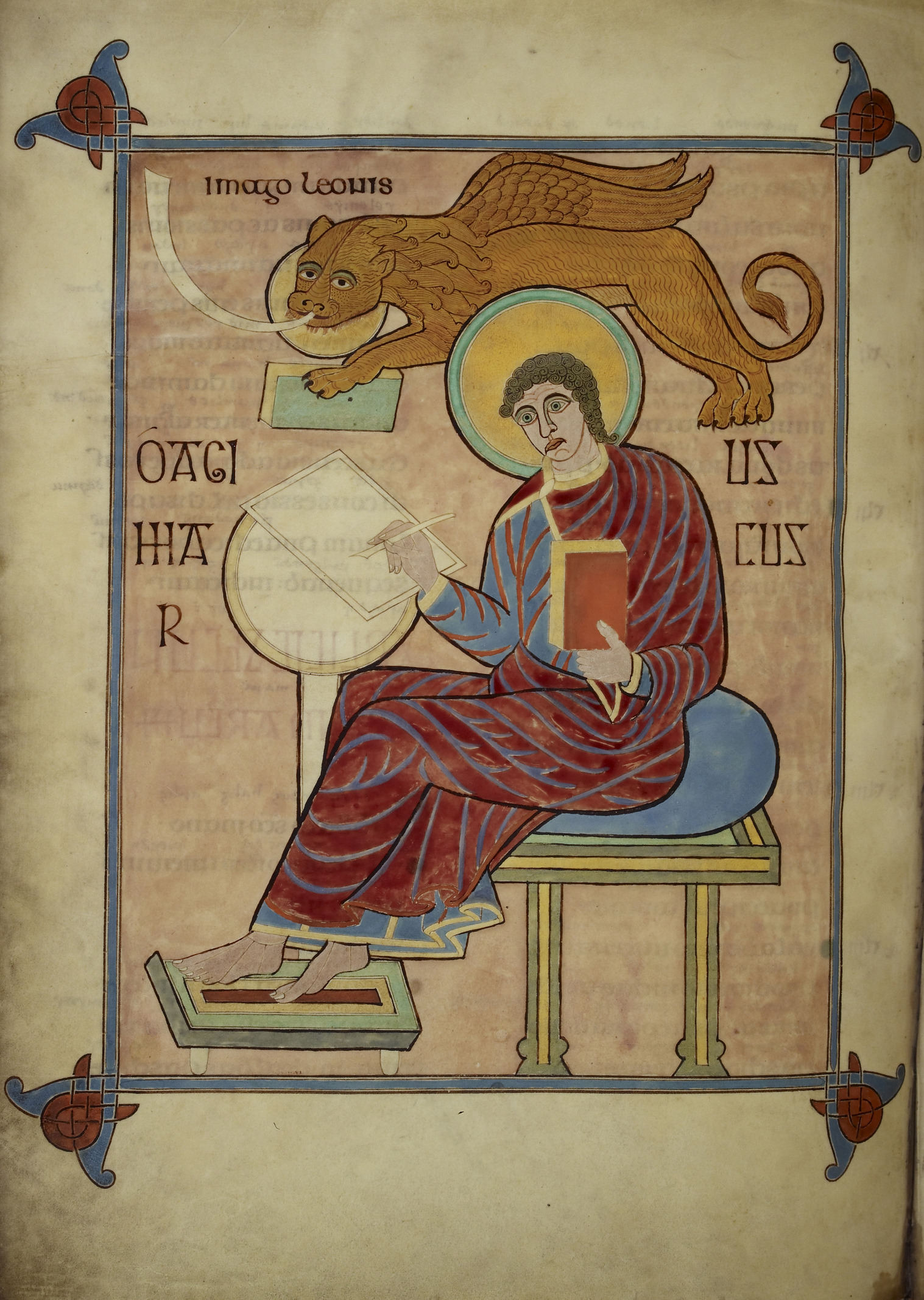

2. **The Enduring Mystery of Authorship: Tradition vs. Scholarship**The attribution of the Gospel of Mark to Mark the Evangelist, famously described as a companion and interpreter of the Apostle Peter, is a tradition deeply rooted in early Christian history. This early Christian tradition, deriving from figures like Papias of Hierapolis, provided an authoritative link for the anonymous text, establishing its credibility within the burgeoning church. It offered a tangible connection to the apostolic witness, crucial for validating its narrative authority.

Yet, contemporary scholarship approaches this traditional attribution with a critical eye, often concluding that the gospel was written anonymously. The prevailing view among many scholars is that the name of Mark was attached to the text at an early stage, not necessarily by the author himself, but to imbue it with an authoritative pedigree. This practice was common in ancient literature, where linking a work to a respected figure could enhance its reception and legitimacy within various communities.

There exist nuances within this scholarly debate, preventing a simple consensus. While some scholars outright deny that the gospel was penned by anyone named Mark, others, such as Helen Bond and Gerd Theissen, argue for homonymity or that the name goes back to the earliest period of circulation, suggesting the author truly was named Mark. Further theories propose authorship by a Mark not explicitly mentioned in the Bible or connected to Peter, highlighting the complex and inconclusive nature of this historical inquiry.

Ultimately, the question of authorship remains largely unresolved, a testament to the challenges of reconstructing ancient literary origins. The lack of definitive internal evidence means that while the traditional attribution provides a comforting narrative, critical scholarship necessitates an acknowledgment of the gospel’s anonymous genesis. This allows for a focus on the text itself, independent of potential later ecclesiastical endorsements, offering a purer lens for its analysis.

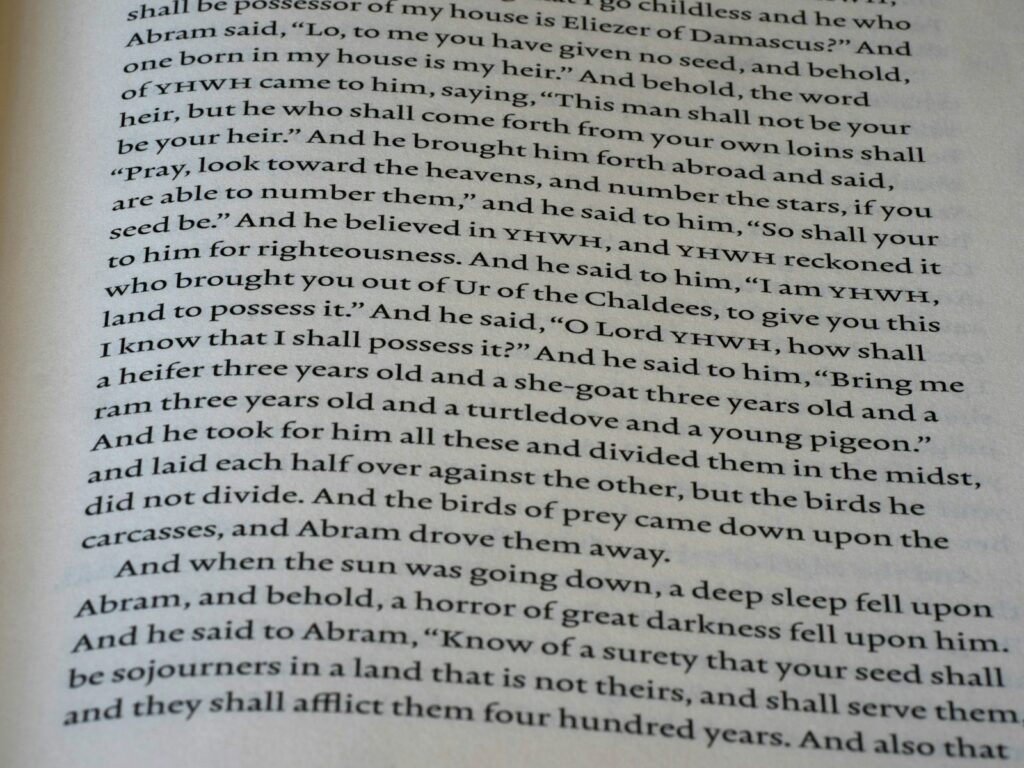

3. **Dating the Narrative: The Historical Echoes of 70 AD**The dating of the Gospel of Mark to approximately 70 AD is not a mere chronological marker but a deeply informed scholarly interpretation, largely anchored in the text’s eschatological discourse, particularly in Mark 13. This specific chapter is widely understood by scholars as containing allusions that point compellingly to the tumultuous events of the First Jewish–Roman War, a conflict that culminated in the devastating destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

This crucial historical event, the Temple’s obliteration in 70 AD, serves as a powerful interpretive lens for dating Mark. Scholars infer that the gospel was composed either immediately following this catastrophic event or during the years directly preceding it, as the destruction would have been a recent, profound, and perhaps anticipated, reality for its original audience. The vivid descriptions within Mark 13 are seen as reflecting the anxieties and experiences of a community living through or reflecting upon such monumental upheaval.

According to Rafael Rodriguez, most scholars place Mark during the build-up of the First Jewish-Roman War, specifically between 65–70 AD, while a substantial plurality dates it shortly afterwards, in the 71–75 AD range. Helen Bond further notes a “growing consensus” for a dating in the early to mid-70s, underscoring the enduring relevance of these historical markers in scholarly deliberations. This precise dating provides a vital context for understanding Mark’s theological and socio-political undertones.

It is important to note that this dating around 70 AD is not solely dependent on the argument that Jesus could not have made an accurate prophecy. Scholars like Michael Barber and Amy-Jill Levine contend that the historical Jesus could indeed have predicted the Temple’s destruction. Nevertheless, the historical proximity of Mark’s composition to the Jewish-Roman War offers compelling evidence for its setting within a period of profound eschatological and nationalistic ferment, shaping its narrative and its urgent message.

Read more about: Unveiling Hidden Fortunes: The Unexpected Millionaires Redefining Home in America’s Trailer Parks

4. **Tailored for a Wider World: The Roman Setting and Gentile Audience**The linguistic and thematic characteristics of the Gospel of Mark strongly suggest it was written in Greek, primarily for a gentile audience. This choice of language and intended readership is crucial for understanding its particular narrative choices and the way it presents Jesus. The broad adoption of Greek as the lingua franca of the Roman Empire meant that a Greek gospel could reach a vastly diverse and geographically dispersed readership, facilitating the spread of the nascent Christian message.

While various locations such as Galilee, Antioch, and southern Syria have been suggested, the overwhelming consensus among modern scholars points to Rome as the most probable setting for Mark’s composition. Theologian Rowan Williams even proposed Libya as a possible setting, citing the location of Cyrene and a long-held Arabic tradition of Mark’s residence there. However, Rome’s prominence as the heart of the empire, and a significant early Christian community, makes it a highly plausible hub for the production of such a foundational text.

The emphasis on a gentile audience is evident in Mark’s narrative style, which often includes explanations of Jewish customs that would be unfamiliar to non-Jewish readers. These contextual clarifications demonstrate a conscious effort to make the story of Jesus accessible and understandable beyond a strictly Jewish milieu. This proactive engagement with a diverse cultural background underscores the early church’s burgeoning mission to transcend its Jewish origins and embrace a broader, multicultural following.

Christianity, originating within Judaism, swiftly spread across the eastern Mediterranean to Rome and further west. The early Christian churches, often small communities based in households, comprised diverse groups. The evangelists, including Mark, wrote on two levels: presenting the historical narrative of Jesus while also addressing the contemporary concerns of their own communities. This dual focus allowed Mark to speak powerfully to both the historical reality of Jesus and the evolving identity of a gentile-inclusive Christian movement in Rome.

5. **Beyond Theology: Mark as an Ancient Biography (Bios)**Modern scholarly consensus largely categorizes the gospels, including Mark, as a subset of the ancient genre of *bios*, or ancient biography. This classification moves away from previous understandings that viewed them as *sui generis* works or purely theological treatises, offering a more precise literary framework for interpretation. Understanding Mark as a *bios* illuminates its narrative purpose and literary conventions, aligning it with a recognized form of ancient writing.

Ancient biographies, unlike modern historical accounts, were not primarily concerned with objective, chronological accuracy in the contemporary sense. Their principal aims were didactic and commemorative: to provide exemplary figures for readers to emulate, to preserve and promote the subject’s reputation and memory, and to convey moral and rhetorical instruction. Mark’s portrayal of Jesus, therefore, serves not just as a factual record but as a compelling model for belief and conduct, embodying these ancient biographical conventions.

Crucially, like all the synoptic gospels, the overarching purpose of Mark’s writing was to strengthen the faith of those who already believed, rather than primarily serving as a tractate for missionary conversion. This focus on internal reinforcement for Christian communities underscores that the text was composed for an audience already invested in the burgeoning Christian movement, seeking to deepen their understanding and resolve in their convictions.

Furthermore, the evangelists often crafted their narratives on two distinct yet interwoven levels. One level presented the “historical” story of Jesus, while the other simultaneously addressed the specific concerns and challenges faced by the author’s own community in their day. For instance, the proclamation of Jesus in Mark 1:14-15 skillfully blends terms familiar to a 1st-century Jew, such as “kingdom of God,” with those pertinent to the early church, like “believe” and “gospel,” creating a resonant message for both historical and contemporary contexts.

6. **The Narrative’s Pivot: Understanding the Structural Break at 8:26–31**While there is currently no universal agreement on the precise overall structure of Mark, a pivotal moment in its narrative arc is widely recognized around Mark 8:26–31. This distinct break functions as a watershed, dramatically shifting the gospel’s focus and geographical setting. It marks a transition that profoundly redefines Jesus’ ministry and the understanding of his identity, moving from public acclaim to private instruction.

Before this crucial juncture, the action of the gospel predominantly unfolds in Galilee, characterized by numerous miracle stories and Jesus preaching to large crowds. He is a healer and miracle worker, capturing public attention and demonstrating divine power. Following Mark 8:31, however, the narrative dramatically shifts. Miracle accounts become scarce, the geographical setting moves away from Galilee towards gentile areas or increasingly hostile Judea, and Jesus’ primary engagement transitions from the masses to a more intense, private instruction of his disciples.

Peter’s confession at Mark 8:27–30, where he declares Jesus as the messiah, serves as the ultimate turning point, the conceptual hinge upon which the entire gospel swings. Immediately after this confession, Jesus begins to explain to his disciples that the Son of Man must suffer, be killed, and rise again. This revelation introduces the theme of the suffering servant, a radical redefinition of messiahship that challenges conventional expectations and sets the course for the climactic events in Jerusalem.

Beyond this primary pivot, scholars have proposed various structural interpretations to capture Mark’s intricate design. R.T. France characterizes Mark as a three-act drama, with a turning point at the end of chapter 10 as Jesus arrives in Jerusalem. Other schemes identify a four-act drama, or even a classic chiasm of ‘Four Series of Seven Days.’ Stephen H. Smith suggests a structure similar to a Greek tragedy, while C. Myers highlights the baptism, transfiguration, and crucifixion as three key apocalyptic moments, each contributing to the multifaceted structural understanding of this compelling narrative.

Having laid the foundational groundwork for understanding the Gospel of Mark’s composition and context, we now pivot to its intricate theological nuances and distinctive narrative details. This section delves deeper into what makes Mark’s account uniquely compelling, exploring its innovative literary devices and the profound implications they hold for interpreting Jesus’ identity and mission. From the enigmatic Messianic Secret to the often-misunderstood portrayal of the disciples, Mark offers a narrative rich with layers for the discerning reader.

7. **The Unveiling of the Messianic Secret: Jesus’ Enigmatic Identity**One of the most profound and consistently debated themes within the Gospel of Mark is the so-called “Messianic Secret,” a concept brought to scholarly prominence by William Wrede in 1901. This motif captures Jesus’ consistent efforts to conceal his identity as the messiah, often commanding demons and those he heals to silence, and presenting the truth through parables in a manner that leaves his own disciples in a state of obtuseness.

The components of this secret are multifaceted, involving Jesus’ silencing of the demons who recognize him, the disciples’ profound failure to grasp his true nature, and the deliberate concealment of divine truth within allegorical stories. Wrede controversially argued that these elements were not historical reflections of Jesus’ practices but rather fictions created by the early church. His theory suggested they served to reconcile the Church’s post-resurrection messianic belief with the historical reality that Jesus had not publicly declared himself the messiah during his earthly ministry.

While Wrede’s interpretation has been widely influential, the “Messianic Secret” remains a focal point of ongoing scholarly debate. The discussion continues regarding the extent to which this secrecy originated with Mark himself, how much he drew from pre-existing traditions, and whether, and to what degree, it authentically represents the historical Jesus’ own self-understanding and pastoral strategies. Regardless of its origin, the Messianic Secret profoundly shapes Mark’s unique Christology, compelling readers to ponder Jesus’ identity as a revelation unfolding through suffering rather than overt declarations.

8. **The Disciples’ Imperfect Journey: A Study in Failure and Redemption**Mark’s Gospel offers a distinctive and often stark portrayal of Jesus’ disciples, particularly the inner circle of the Twelve. Their journey is characterized by a gradual descent from initial lack of perception regarding Jesus’ teachings and miracles to an outright rejection of the “way of suffering” that Jesus articulates. Ultimately, their narrative culminates in moments of flight and profound denial, most notably Peter’s triple denial of Christ.

This negative depiction has spurred considerable scholarly discussion, with various interpretations seeking to explain its purpose. Some scholars propose that Mark was intentionally using the disciples’ failures to correct “erroneous” views prevalent within his own community, particularly concerning the true nature of the suffering messiah. Others suggest it might serve as a critique against the Jerusalem branch of the early church for its resistance to extending the gospel to gentiles, or perhaps as a poignant mirror of the typical convert’s experience—an initial enthusiasm giving way to a more challenging awareness of the necessity for suffering in faith.

Crucially, this theme of disciples’ failure resonates deeply with the strong theological motif in Mark of Jesus as the “suffering just one,” a figure echoed throughout Jewish scriptures from Jeremiah to Job and the Psalms, most notably in the “Suffering Servant” passages of Isaiah. It also reflects the broader Jewish scripture theme of God’s enduring love being met by infidelity and failure, only to be continually renewed by divine grace. In this light, the disciples’ shortcomings, and even Peter’s stark denial, become powerful symbols of faith, hope, and reconciliation for nascent Christian communities grappling with their own imperfections.

9. **Miracles and the Mien of Mysticism: Jesus’ Unique Healing Modalities**Miracles are not just episodic events in the Gospel of Mark; they are integral to its narrative, accounting for almost a third of the text and half of its first ten chapters. While these supernatural acts primarily serve as compelling evidence of God’s rule, Mark’s descriptions of Jesus’ healings exhibit certain characteristics that set them apart, often bearing a resemblance to the methods employed by ancient magicians.

Mark meticulously details Jesus’ unique healing modalities, which include the use of physical elements and specific pronouncements. Notably, Jesus is depicted using spittle to heal blindness, as seen in the accounts of the blind man at Bethsaida (Mark 8:23) and the deaf-mute man in the Decapolis (Mark 7:33). Furthermore, Mark records Jesus employing Aramaic words and phrases that function almost like potent formulae, such as “Talitha koum” (meaning “Little girl, I say to you, get up!”) to raise Jairus’s daughter (Mark 5:41) and “Ephphatha” (meaning “Be opened!”) to heal the deaf-mute man (Mark 7:34).

These distinctive methods did not go unnoticed, even by Jesus’ contemporaries. The Jewish religious leaders, in particular, leveled charges against him, alleging that he performed exorcisms with the aid of an evil spirit or even called upon the spirit of John the Baptist. Mark, however, vehemently defends Jesus against such accusations, crucially framing his miracles as acts performed through divine authority and as an instrument of God, not Satan. The gospel also presents unique healing narratives, such as Jesus laying his hands on a blind man twice to effect a cure (Mark 8:23–25), showcasing a process of gradual restoration that offers a layered understanding of divine intervention.

10. **Enigmatic Figures and Unique Character Details**The Gospel of Mark distinguishes itself not only through its theological depth but also through its inclusion of highly specific and often enigmatic character details that provide a unique flavor to its narrative. Among the most intriguing is the fleeting appearance of a ” young man” who flees when Jesus is arrested in Gethsemane (Mark 14:51-52). This mysterious figure, who appears abruptly and vanishes just as quickly, has puzzled scholars for centuries, sparking numerous theories about his identity and symbolic significance.

Intriguingly, Mark presents another solitary “young man in a white robe” at the empty tomb, who announces Jesus’ resurrection to the women (Mark 16:5-7). While distinct from the figure in Gethsemane, the parallel imagery of a youthful, robed figure at pivotal moments of Jesus’ passion and resurrection invites compelling speculation about a recurring symbolic presence or perhaps an implied eyewitness within Mark’s narrative framework.

Beyond these mysterious figures, Mark also provides other unique character insights. For instance, the gospel is the only one to specifically name the sons of Simon of Cyrene, Alexander and Rufus (Mark 15:21), implying their familiarity or importance to Mark’s original audience. This specific detail humanizes the moment of the crucifixion and suggests a community with personal connections to the events. Furthermore, Mark is the sole canonical gospel to explicitly refer to Jesus himself as a “carpenter” (Mark 6:3), diverging from Matthew’s description of him as a “carpenter’s son.” This subtle yet powerful distinction presents Jesus as directly engaged in a manual profession, offering a unique glimpse into his earthly life and identity.

Read more about: Gene Hackman, Hollywood’s Consummate Everyman, Dies at 95: A Life Forged in Intensity and Nuance

11. **The Nuance of Christology: Unpacking “Son of God” and “Son of Man”**In the tapestry of Mark’s Christology, “Son of God” emerges as the most paramount and frequently debated title ascribed to Jesus. This designation is powerfully affirmed on the lips of God himself during both Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration, and it is also Jesus’ own implicit self-designation. However, the precise meaning and implications of this title for Mark and his 1st-century audience remain a complex subject of scholarly inquiry, reflecting diverse cultural and theological understandings.

The term “Son of God” carried a spectrum of meanings in ancient contexts. In Hebrew Scriptures and among Jews, it could refer to angels, the nation of Israel as God’s chosen people, a righteous sufferer, or an earthly king adopted by God at his enthronement. Conversely, in Hellenistic culture, the phrase often denoted a “divine man” or a supernatural being, encompassing legendary heroes, god-kings, or esteemed philosophers. This dual cultural backdrop fuels scholarly debate, with figures like Strecker and Telford arguing that Mark portrays Jesus more as a Hellenistic “divine man,” signaling a shift from Jewish-Christian messianic conceptions, while others like Luz and Baum emphasize a strong alignment with Hebrew Bible styles.

Mark also employs other vital Christological titles, notably “Christos” (translating the Hebrew “messiah”) and “Son of Man.” For Mark, the title “Christos” is most potently understood in the context of Jesus’ suffering and death, radically redefining conventional expectations of a victorious messianic king. The title “Son of Man,” deeply rooted in apocalyptic Jewish works like the Book of Enoch and Daniel 7:13–14, assigns Jesus royal dominion and glory, particularly in climactic scenes like Mark 14:62 where he is prophesied to be seated at God’s right hand and to come on clouds.

Ultimately, Mark interweaves these three significant titles—Christ, Son of God, and Son of Man—into a cohesive yet complex Christological portrait. While each title carries distinct nuances, their common thread converges on the concept of kingly power, profoundly reinterpreted through the lens of suffering, sacrifice, and ultimate vindication. This multifaceted portrayal invites readers to a deeper, more challenging understanding of Jesus’ identity and divine mission.

12. **Distinctive Narrative Strokes: Mark’s Exclusive Content**The individuality of the Gospel of Mark is further underscored by a series of narrative details and pronouncements found exclusively within its pages, providing a unique perspective often absent from its synoptic counterparts. These distinct strokes lend a particular character to Mark’s account of Jesus’ life and ministry, inviting a closer examination of its singular theological emphases and historical context.

One such pivotal and exclusive declaration is Jesus’ profound statement, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27). This powerful assertion, which significantly reconfigures the interpretation of legalistic observance, is conspicuously absent from the parallels found in Matthew 12:1–8 and Luke 6:1–5, highlighting Mark’s unique emphasis on Jesus’ authority over traditional law.

Mark also includes the singular “Parable of the Growing Seed” (Mark 4:26–32), a parable found only in this gospel. It beautifully illustrates the mysterious and organic growth of God’s kingdom, emphasizing that its progress is ultimately God’s work, independent of human effort, a theological insight not shared directly by the other synoptics. Another vivid, quantitative detail unique to Mark is the precise count of “about two thousand” possessed swine in the story of the Gerasene demoniac (Mark 5:13), lending a dramatic and almost cinematic quality to the narrative that intensifies the scale of the miraculous event.

Further distinguishing Mark’s narrative are specific instructions and references. Only in Mark 6:8–9 are the disciples explicitly permitted to take a “staff and sandals” for their mission, a detail that contrasts with the prohibitions found in Matthew 10:9–10 and Luke 9:3, revealing a subtle difference in the practical guidance for early evangelism. Moreover, Mark is the sole gospel to refer to Herod Antipas as a “king” (Mark 6:14), rather than the more historically precise “Herodian tetrarch” used by Matthew and Luke, possibly reflecting a simplification of titles for Mark’s predominantly gentile audience.

Finally, Mark stands alone in offering some of the most dramatic and ambiguous details surrounding Jesus’ passion and resurrection. This includes the unique mention of “the cock crows ‘twice'” as predicted during Peter’s denial (Mark 14:30, 72), providing a heightened sense of fulfilled prophecy and Peter’s personal shame. These exclusive details, from the mundane to the miraculous, collectively paint a distinct and compelling portrait of Jesus and the unfolding of God’s kingdom as uniquely conceived and presented by Mark.

As we conclude this in-depth exploration of the Gospel of Mark, it becomes evident that this ancient text is far more than a mere historical record. It is a work of sophisticated theological artistry, meticulously crafted to strengthen the faith of its readers and challenge their perceptions. From its foundational assertions to its distinctive narrative strokes and profound Christological insights, Mark continues to resonate, offering a vivid and urgent account of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. It is a narrative that, centuries after its composition, still powerfully invites engagement with the enduring questions of faith, identity, and divine purpose, proving its timeless relevance in the grand narrative of Christianity.