Depression and heart disease represent two of the most prevalent and debilitating health challenges facing individuals today. While often viewed as distinct ailments affecting different organ systems, an ever-growing body of evidence highlights a profound and complex two-way relationship between them. This intricate connection means that these conditions frequently co-occur, profoundly impacting patient outcomes and quality of life. Understanding this relationship is crucial for both healthcare providers and patients alike, enabling more comprehensive care strategies.

This article aims to provide an in-depth exploration of how depression and heart disease are intertwined, drawing upon current research and expert insights to illuminate various facets of this critical health issue. We will delve into the psychological ramifications of cardiac events, discuss the crucial support systems available for recovery, and examine how a patient’s mental state can significantly influence their heart health trajectory. Our focus will extend to recognizing the challenges in diagnosing depression when heart disease is present, and addressing specific vulnerabilities, particularly for women.

By dissecting these interconnected factors, we seek to empower readers with knowledge that underscores the importance of addressing mental health as an integral component of cardiovascular care. The journey through heart disease recovery is multifaceted, and recognizing the critical role of emotional well-being is paramount. We will explore key aspects that shape this experience, offering clarity on a topic that demands greater awareness and integrated medical approaches for better patient outcomes.

1. How Depression and Heart Disease Relate to Each Other

The co-occurrence of depression and heart disease is not merely coincidental; a compelling body of thought suggests a bidirectional relationship between these two conditions. This means a cardiac event can predispose an individual to depression, and pre-existing depression can elevate heart disease risk. The context states that “A percentage of people with no history of depression become depressed after a heart attack or after developing heart failure,” highlighting the direct psychological aftermath of a serious cardiac diagnosis.

Conversely, individuals diagnosed with depression but previously showing no signs of heart disease “seem to develop heart disease at a higher rate than the general population.” This suggests depression itself might act as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular issues. Pinpointing the exact causal chain can be challenging, as some with undiagnosed prior depressive episodes might only receive a formal diagnosis once seeking medical attention for heart problems, making it “somewhat hard to prove that heart disease directly leads to the development of a first-ever episode of depression.”

However, their frequent co-existence remains unequivocally clear. Cardiologist Dr. Roy Ziegelstein states with certainty that “depression and heart disease often occur together.” The statistics are striking: “About one in five who have a heart attack are found to have depression soon after the heart attack,” and this prevalence is “at least as prevalent in people who suffer heart failure.” These figures underscore the widespread nature of this dual burden on patients and healthcare systems. Recognizing this strong association is the first step toward integrated care, as addressing depression is a critical component of holistic heart health management.

Read more about: Unlock Your Brain’s Full Potential: 14 Essential Steps for Lifelong Cognitive Health

2. The Profound Psychological Impact of a Heart Attack

A heart attack is a life-altering event that extends its impact far beyond physical damage to the heart muscle. The psychological reverberations can be profound, touching numerous aspects of an individual’s life. This emotional toll often contributes to or exacerbates depressive symptoms in survivors, with the disruption to one’s sense of self and future being immense.

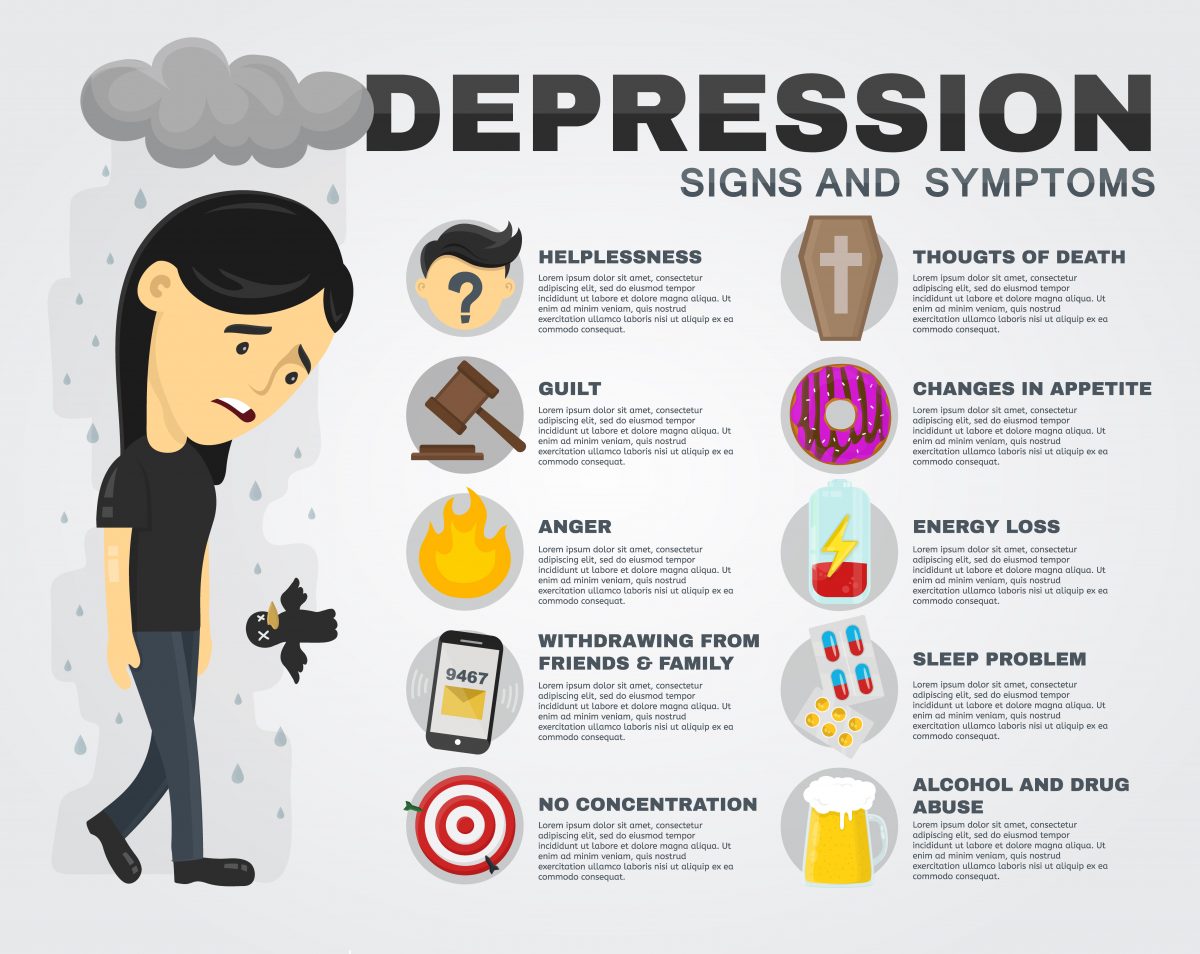

The context identifies several key areas where a heart attack can profoundly affect a person’s life. These include their “Attitude and mood,” which can swing dramatically. Equally significant is the erosion of their “Sense of certainty about the future.” Before a cardiac event, health might be taken for granted; afterwards, life can feel unpredictable and fragile, leading to anxiety and loss of perceived control.

Furthermore, a heart attack can deeply shake a person’s “Confidence about one’s ability to fulfill the roles of a productive employee, mother, father, daughter, or son.” Sudden physical limitations and perceived vulnerability can lead to intense “Feelings of guilt about previous habits that might have increased the person’s heart attack risk.” This self-blame, whether rational or not, can be a heavy emotional burden. Added to this is the potential for “Embarrassment and self-doubt over diminished physical capabilities,” deterring re-engagement in activities or daily tasks.

While “Most heart attack survivors are able to return to the roles and responsibilities they had before their heart attack,” for some, this return is not straightforward. When uncertainty and anxiety become “debilitating and interfere with the daily functions of life,” it signals a need for more specialized support. In such cases, recovery must expand beyond physical rehabilitation to include “psychological and psychiatric support, and perhaps medication for depression,” addressing mental health as rigorously as cardiac recovery.

Read more about: Seriously, Ouch! 14 Unforgettable Times Actors’ Real Pain Was Captured on Film

3. Comprehensive Support Systems for Heart Event Recovery

Recovering from a heart attack or any other serious cardiac event is a complex journey, often requiring multifaceted support. Beyond immediate medical interventions, individuals can greatly benefit from resources addressing both physical and psychological needs. These support systems play a vital role in helping patients regain their health, confidence, and overall well-being.

One cornerstone of physical recovery is “cardiac rehabilitation.” This involves “supervised forms of exercise in many clinical exercise centers,” such as those at Johns Hopkins. These programs are not just about physical activity; they often include a carefully “monitored program” with an “activity and nutrition plan specifically developed for heart attack recovery.” Studies compellingly show that “returning to normal activity and seeing the progress of other people recovering from a heart attack significantly improves mood and confidence.” This communal aspect fosters shared experience and motivation.

Beyond structured rehabilitation, “social support” is critically important. It is entirely “natural to withdraw and lose social confidence after a heart attack,” as the experience can be isolating and frightening. However, research suggests that actively “making an extra effort to re-engage and socialize with friends can help you return to the person you were before, which can be vital to heart attack recovery.” Reconnecting with one’s social network provides emotional validation, reduces feelings of isolation, and helps normalize the recovery experience.

For some individuals, the psychological impact is profound enough to warrant “more formal forms of support.” When symptoms of depression or anxiety persist, professional guidance becomes essential. This may involve a “psychiatrist, psychologist, or psychiatric social worker.” Many “milder forms of depression can be successfully treated by behavioral or ‘talk’ therapy,” delivered “either one-to-one or in a group of heart attack recovery patients.” For more severe symptoms, “depression symptoms may require antidepressant medication,” administered under medical supervision. These varied support options underscore the comprehensive approach needed for true recovery.

Read more about: Unpacking the Method: The Extreme Techniques and Divisive Practices of Method Acting That Sparked On-Set Drama

4. The Relationship Between Mood, Heart Disease, and Heart Attack Recovery

The relationship between mood, heart disease, and heart attack recovery is critically important, as an individual’s mental state can profoundly influence their physical prognosis. Patients with depression or recovering from a heart attack face a “lower chance of recovery and a higher risk of death than people without depression.” This stark reality underscores the need to treat depression as a serious co-morbidity in cardiac patients. Reasons for this amplified risk are multifaceted, encompassing both behavioral patterns and physiological responses.

Behaviorally, depression can significantly impede recovery by eroding motivation. “In depressed heart attack patients, decreased motivation to follow healthy daily routines can result in skipping important heart medications, avoiding exercise and proper diet, and continuing or intensifying smoking and drinking habits.” These actions directly contradict essential lifestyle changes for cardiovascular health and preventing future cardiac events. This cycle of low mood leading to poor adherence becomes a significant barrier to effective recovery.

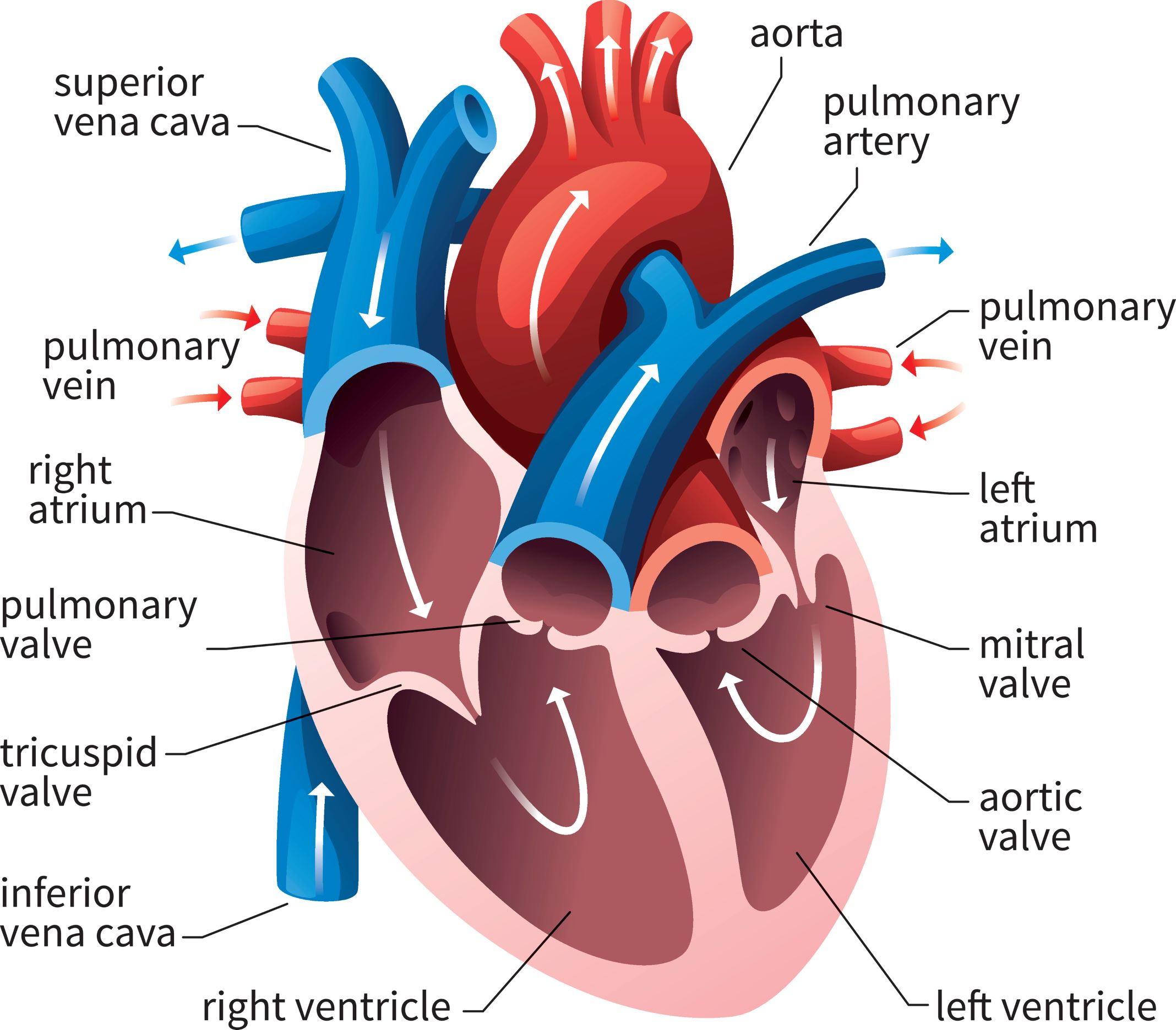

Physiologically, depression can induce detrimental changes within the body’s systems. Individuals with depression “can also experience changes in their nervous system and hormonal balance,” which in turn “can make it more likely for a heart rhythm disturbance (called an ‘arrhythmia’) to occur.” This heightened susceptibility to arrhythmias, particularly when combined with a heart already “damaged (from a heart attack),” renders these patients “particularly susceptible to potentially fatal heart rhythm abnormalities.” The physiological stress inflicted by depression exacerbates the heart’s vulnerability.

Furthermore, depression can affect the body’s clotting mechanisms. “People with depression may have uncommonly sticky platelets, the tiny cells that cause blood to clot.” In heart disease, this condition can accelerate “atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries)” and significantly “increase the chance of heart attack.” Encouragingly, some studies suggest that “treating depression make platelets less sticky again,” offering a tangible biological benefit from addressing mental health. This intricate interplay of psychological, behavioral, and physiological factors highlights why an integrated approach to care is often lifesaving.

Read more about: Unlock a Healthier You: 14 Profound Changes Your Body Experiences When You Go Alcohol-Free for 30 Days

5. The Effect of a Positive Mental State on Heart Disease

While the negative impacts of depression on heart health are well-documented, the converse also holds true: maintaining a positive mental state can have a powerfully beneficial effect on heart disease outcomes. A person’s attitude and belief in their ability to influence their own health are crucial determinants of successful recovery and prevention. This highlights the importance of fostering psychological resilience alongside medical treatment.

“Maintaining a positive attitude about treatment and holding the belief that our actions can have a beneficial effect on our own health are very important.” This internal conviction empowers individuals to take active control of their health journey. A positive mindset “seems to have a powerfully favorable effect on their ability to make behavior and lifestyle changes that are often necessary to reduce the risk of having future heart problems.” This includes adhering to medication, embracing exercise, and adopting healthier dietary habits—all critical for long-term cardiovascular well-being.

The influence of attitude extends beyond behavior to the very “response to treatment.” Two key concepts are particularly relevant here: the “healthy adherer” and “self-efficacy.” The term “healthy adherer” describes individuals who consistently take their medicines as directed. Studies show a significant difference in outcomes: “Those who take their medications as directed (also known as ‘good adherers’) have a lower death rate than those who don’t (poor adherers).” Beyond medication, these individuals “may also diligently follow daily habits that are healthy for the heart, such as proper diet and exercise.”

“Self-efficacy” complements this by describing “a person’s beliefs about their ability to do certain things in order to reach a desired outcome, or to influence events in their life.” When it comes to heart health, “The self-confidence that our actions can have a positive effect on our health (e.g. losing weight and exercising can lower our risk for heart disease) is very important in determining how motivated we are to engage in behaviors that are good for us.” Fostering this belief in one’s capacity to enact positive change can be a powerful therapeutic tool, promoting active participation in managing and improving heart health.

Read more about: Beyond the Buzzwords: Unmasking the Truth Behind 17 Fast Food Claims That Might Be Playing Tricks on Your Diet

6. Challenges in Recognizing Depression Symptoms Alongside Heart Disease

One significant hurdle in effectively managing co-occurring heart disease and depression lies in the challenge of symptom recognition. Both conditions can manifest with overlapping symptoms, making it difficult for patients, their families, and even healthcare providers to distinguish between them. This diagnostic ambiguity can lead to delays in appropriate mental health intervention, impacting overall patient care.

The context explicitly points out that “Heart disease and depression often carry overlapping symptoms such as fatigue, low energy, and difficulty in sleeping and carrying on the daily rhythms of life.” These are common complaints in individuals recovering from a cardiac event, which can naturally cause exhaustion and physical limitations. Consequently, it is “not surprising that sometimes symptoms of depression are thought of by the patient, the patient’s family, and the cardiologist as being due to heart disease.” This misattribution can inadvertently prevent timely diagnosis and treatment of underlying depression.

Many medical community members “have stressed the importance of having patients, families, and physicians gain a greater awareness of the prevalence of post-heart attack depression.” Heightened awareness is the first step toward better detection. Physicians, in particular, “need to understand the importance of treating depression, since it is treated differently from heart disease.” While some symptoms may overlap, the therapeutic approaches for each condition are distinct and specialized.

Meeting this challenge requires open and proactive communication. This “can result in a vital communication between patient and physician that can start with something as simple as, ‘I wonder if what I’m feeling is from depression.'” Such a question can open the door to a crucial dialogue, prompting physicians to screen for depression and consider its unique treatment protocols. Encouraging patients to voice their emotional concerns is paramount to overcoming diagnostic ambiguity and ensuring comprehensive care.

Read more about: Beyond Forgetfulness: Understanding the 10 Early Warning Signs of Alzheimer’s Disease

7. Heart Disease and Depression: Unique Considerations for Women

When examining the intricate relationship between heart disease and depression, it is crucial to acknowledge specific considerations for women. Research consistently shows that women face unique challenges and present distinct patterns in the co-occurrence of these conditions, demanding tailored healthcare approaches. Understanding these differences is vital for providing equitable and effective care.

One significant factor is the general prevalence of depression, which is “generally more common in women than in men.” This baseline difference means that “women with heart disease are more likely to develop depression” due to this demographic predisposition. The interplay between gender, mental health, and cardiovascular health creates a particularly vulnerable profile for women facing cardiac issues. This heightened risk requires proactive screening and support.

Beyond biological and demographic factors, social circumstances often play a considerable role. The context highlights that “Heart disease tends to affect older individuals, and approximately one third of women recovering from a heart attack live alone, with no immediate family member or spouse to turn to for physical and emotional support.” This lack of immediate social and emotional scaffolding can exacerbate feelings of isolation, anxiety, and depression during a demanding recovery period. The absence of a built-in support network is a significant disadvantage.

Dr. Ziegelstein emphasizes the responsibility of healthcare providers: “It’s important for all of us as healthcare providers to recognize that while we can’t necessarily change someone’s living situation or stress level, we can recognize their unique circumstances.” This recognition is not merely empathetic; it informs the development of personalized care plans. He adds, “We can work with our patients on this individual level to help them cope with life in healthier ways,” suggesting interventions that consider social support gaps and stress management. The Johns Hopkins Women’s Cardiovascular Health Center is an example of specialized care, underscoring gender-specific approaches.

8. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a crucial neuroendocrine system that governs the body’s stress response and maintains physiological balance. Its intricate feedback loops are vital, and any dysregulation can profoundly impact both cardiovascular health and mental well-being. Understanding the HPA axis’s function is essential for elucidating the complex connections between depression and heart disease.

Glucocorticoids, particularly cortisol, play a significant role in coronary artery disease (CAD). Excessive cortisol, often signaling HPA axis overactivity, is linked to cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia, accelerating atherosclerosis. Conversely, a downregulation of basal HPA axis activity has been associated with a poorer cardiovascular prognosis, potentially by promoting a hypercoagulable state. This highlights the HPA axis’s multifaceted influence on cardiac health.

The HPA axis is also central to the pathophysiology of anxiety, depression, and cognitive dysfunction. The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in the brain is critical for depression’s development. Studies consistently show notable cortisol disparities in depressed individuals, with higher cortisol negatively affecting cognitive performance. In patients with both CAD and depression, specific HPA axis alterations are observed, including lower plasma and salivary cortisol and reduced GR expression, pointing to a unique neuroendocrine profile in this comorbid population.

Read more about: Unmasking the Mystery: Why Your Vitamin D Supplement Isn’t Working – Exploring 9 Critical Absorption Killers and Solutions

9. The Role of Inflammation

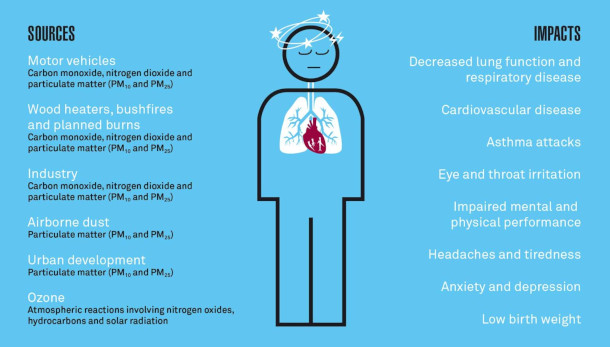

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is fundamentally characterized by the formation of arterial plaques, heavily influenced by inflammatory cells. Inflammation is a critical driver in CAD’s onset and progression. Biomarkers like IL-6, CD40, CRP, complement, and MPO can indicate disease severity; for instance, activated CD40 on macrophages, through TRAF6, is crucial in atherogenesis and atherosclerosis progression.

Inflammation also significantly contributes to depression. Meta-analyses reveal higher serum levels of inflammatory markers such as sIL-2R, TNF-α, and IL-6 in major depression patients, signifying a systemic inflammatory state. The tryptophan-kynurenine pathway is implicated here, where increased IL-6 enhances IDO activity, leading to neurotoxic byproducts like quinolinic acid that contribute to severe depression and neurodegeneration.

Research suggests inflammation acts as a common link between both conditions. A large UK Biobank study identified IL-6, CRP, and triglycerides as potentially causal factors for depression, proposing them as therapeutic targets. Psychological stress can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, releasing IL-1 and contributing to systemic diseases like CVD. Furthermore, studies in depressed patients with major depression show mild inflammation, elevated monocyte counts, and heightened systemic immune-inflammatory indices, with monocyte count specifically linked to coronary heart disease risk, reinforcing inflammation’s pivotal role.

Read more about: Beyond the Red Carpet Glow: Unpacking the 12 Most Controversial Beauty Treatments Hollywood Stars Actually Swear By

10. Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic alterations are prevalent in altered mood states, serving as a primary physiological mechanism connecting depression to various physical dysfunctions. Reduced heart rate variability (HRV), indicating vagal withdrawal and decreased parasympathetic influence, is a key marker. Rodent studies confirm that social stress triggers depression-like behaviors and cardiovascular changes, including reduced HRV, consistent with excessive sympathetic drive.

Evidence strongly supports autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction in depressed patients with coronary artery disease. This manifests as rapid heartbeat and low heart rate variability, reflecting heightened bodily stressors and impaired cardiac regulation. The relationship between inflammatory markers and autonomic function is amplified in depressed cardiac patients, suggesting a detrimental synergy between inflammation and ANS dysregulation.

Reduced HRV and stress reflex sensitivity are independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and both are diminished in depressed patients. A linear correlation exists between depression severity and HRV, with severely depressed individuals experiencing a significantly higher incidence of arrhythmias, particularly supraventricular types. This implies depression directly relates to cardiac ANS dysfunction, increasing susceptibility to early-onset atrial and/or ventricular disease. Moreover, a -dependent link between major depressive disorder and cardiac autonomic dysfunction offers insights into gender differences in cardiovascular disease incidence.

Read more about: Ozzy Osbourne: Official Causes of Death Revealed for Rock Legend Aged 76

11. The 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) System

The 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), or serotonin, system is a stress-sensitive neurotransmitter system tightly linked to circadian rhythms and frequently involved in depression. Its discovery, revealing 5-HT reuptake mechanisms, paved the way for modern antidepressants like SSRIs, which boost serotonin availability. As both a neurotransmitter and peripheral hormone, 5-HT is vital in the pathophysiology of both depression and cardiovascular disease.

Stress-induced disruptions to the 5-HT system can interfere with circadian rhythms, increasing depression susceptibility. The 5-HT1A auto-receptor modulates neuronal responses, and chronic SSRI treatment desensitizes it, enhancing 5-HTergic activity. In the human heart, 5-HT4 receptor isoforms mediate contractile, chronotropic, and proarrhythmic effects, with altered expression in cardiovascular disease.

The 5-HT system is highly relevant to stroke and post-stroke depression (PSD), a common issue for survivors. Studies show higher 5-HT and 5-HT2 receptor levels in stroke patients, suggesting serotonin’s direct role in vascular pathology. SSRIs are used clinically for PSD, confirming the importance of 5-HT transporters and receptors. Furthermore, 5-HT2AR antagonists and synthesis inhibitors demonstrate synergistic effects in inhibiting atherosclerotic plaque formation.

SSRIs reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, possibly by affecting serotonin and platelet abnormalities in treated depressed patients. Complex interactions within serotonin receptor complexes, like 5-HT1AR and 5-HT2AR, are crucial for mood. Disruptions in these interactions may contribute to major depression. Research indicates higher serotonin receptor density in CAD patients with depression, and a specific S allele in the SERT gene links to higher recurrent cardiac event risk in AMI patients, partially through depressive symptoms.

12. MicroRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs crucial for gene expression regulation, acting as key controllers in cardiovascular disease. Circulating miRNAs are increasingly recognized as potential novel prognostic biomarkers for conditions like coronary artery disease and acute myocardial infarction, offering new tools for diagnosis and risk assessment.

MiRNAs are also implicated in the intersection of depression and cardiovascular health. Some studies suggest miRNAs, along with brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), play a role in depression co-occurring with essential hypertension. Specific miRNAs, such as miR-499 and miR-133a, are considered potential biomarkers for acute myocardial infarction. MiR-665, for instance, is elevated in ischemia/reperfusion injury models, with its overexpression reducing cardiac damage and apoptosis markers.

In mental health, miR-1202 is consistently dysregulated in major depression patients’ brains and blood, and its peripheral variations correlate with antidepressant treatment response, suggesting its role in depression’s pathophysiology. Hsa-miR-107 links APOEε4, depressive symptoms, and cognitive impairment. MiR-132 affects both neurological and cardiovascular systems; stress reduces BDNF, leading to miR-132 downregulation, impacting neuroplasticity and depression, and influencing cardiovascular function via the ANS and HPA axis.

Other miRNAs include miR-21, found lower in the white matter of individuals with depression and alcoholism, correlating with myelin proteins, indicating its involvement in white matter changes. A study also found that cardiovascular patients carrying a specific C allele in miR-146a rs2910164 had a reduced risk of depression, potentially by altering miR-146a expression and increasing its target gene, NOS1, highlighting direct molecular pathways influencing depression risk in cardiac patients.

13. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

Patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) often have lower omega-3 fatty acid concentrations, suggesting a therapeutic opportunity. Supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids has demonstrably improved cardiovascular prognosis in patients with heart disease and heart failure. The GISSI-HF trial, for example, showed that EPA and DHA supplementation significantly enhanced survival and reduced rehospitalizations in heart failure patients.

Omega-3 fatty acids also substantially lower the risk of sudden death from arrhythmias and all-cause mortality in established CAD. They aid in managing hyperlipidemia and hypertension. Major health bodies recommend regular fish consumption and specific daily EPA and DHA intake for cardioprotection, recognizing their crucial role. N-3 PUFAs improve vascular and cardiac hemodynamics, enhance endothelial function, autonomic control, and reduce inflammation, arrhythmias, and thrombosis.

The mental health link is equally vital, as depressed individuals often exhibit reduced n-3 PUFA levels across various tissues, including the brain. Chronic n-3 PUFA deficiency can alter brain ω-3 PUFA concentrations, impacting 5-HT2 and D2 receptor density in the frontal cortex—pathways central to depression’s pathophysiology. This directly connects nutritional status to brain chemistry and mood regulation.

Clinical research supports this, with a controlled study confirming ω-3 PUFAs’ adjunctive mood-stabilizing effect in bipolar disorder, showing better treatment outcomes. Severe mental illness patients often have a low omega-3 index, correlating with high cardiovascular disease mortality risk. While patient heterogeneity causes some variability, the consistent finding is that n-3 PUFAs are strongly associated with depression, especially when precisely defined, underscoring their critical role in both cardiac and mental well-being.

Read more about: Empowering Your Plate: 14 Dietary Strategies to Significantly Lower Your Cancer Risk

14. The Intestinal Flora (Gut Microbiome)

The intestinal flora, or gut microbiome, is an emerging research area with significant implications for preventing and treating coronary heart disease (CHD). Strategies like probiotic supplementation and altering microbiota composition are actively explored, leveraging the profound connection between gut health and cardiovascular well-being. The gut is now recognized as a critical modulator of systemic health.

Pathological conditions in the gastrointestinal tract can compromise the intestinal barrier, allowing bacteria and their metabolites to translocate to distant organs like the heart. This process is increasingly understood to contribute to systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease evolution, underscoring the gut-heart axis. Specific gut microbiota-dependent metabolites, such as phenylacetylglutamine (PAG) and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), have been linked to increased CVD risk in large clinical studies, serving as potential biomarkers.

A whole metagenome study comparing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease patients to healthy controls revealed significant deviations in the gut microbiome of CVD patients. This included increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and Streptococcus spp., indicating a distinct microbial signature associated with cardiovascular pathology. These findings suggest that gut dysbiosis can directly contribute to heart disease development and progression.

The gut microbiome also profoundly impacts mental health. Depression is strongly associated with variations in gastrointestinal microbiota; for example, Irritable Bowrome (IBS), with altered gut flora, is linked to depression. Changes in gut flora can worsen depressive symptoms and trigger the stress response. Conversely, some studies suggest gut microbes can mitigate stress- and depression-related symptoms by modulating brain function. Research consistently finds specific bacterial taxa differences in the gut microbiota of individuals with major depression, solidifying the gut microbiome’s role as a dynamic factor in the intricate interplay between depression and cardiovascular health.

As we navigate the complex landscape of health, it becomes increasingly clear that the heart and mind are not isolated entities, but rather deeply interconnected systems influencing each other in myriad ways. From the intricate hormonal dances of the HPA axis to the silent orchestrations of microRNAs and the profound influence of our gut’s microbial residents, these biological mechanisms offer a window into the holistic nature of well-being. By embracing this comprehensive understanding, integrating mental health considerations into cardiovascular care, and exploring these cutting-edge insights, we can forge a path towards more effective prevention, treatment, and ultimately, a healthier future for all.