The United States Constitution stands as a monumental achievement, a living blueprint that has guided the nation for over two centuries. It’s the supreme law of the land, establishing the framework for our government and safeguarding the fundamental rights and liberties we cherish. While most Americans recognize its importance, the intricate details of its origin, the fierce debates that shaped it, and the surprising facts embedded within its history often remain obscure, hidden behind the grand narrative.

This enduring document replaced the Articles of Confederation, forging a more robust federal system and laying the foundation for modern American governance. From its drafting in Philadelphia to its ultimate ratification, the journey of the Constitution was filled with moments of intense deliberation, bold decisions, and even strategic secrecy. Understanding these foundational elements allows us to appreciate its resilience and flexibility, which have enabled it to remain relevant through centuries of societal and technological change.

We’re about to embark on a fascinating exploration, uncovering twelve lesser-known facts about the U.S. Constitution that offer a deeper, richer understanding of this cornerstone of American democracy. Prepare to look beyond the surface and discover the surprising stories and deliberate choices that crafted the document shaping our daily lives, from freedom of speech to the right to a fair trial. Let’s dive in and get smarter on the intricate tapestry of our nation’s founding charter.

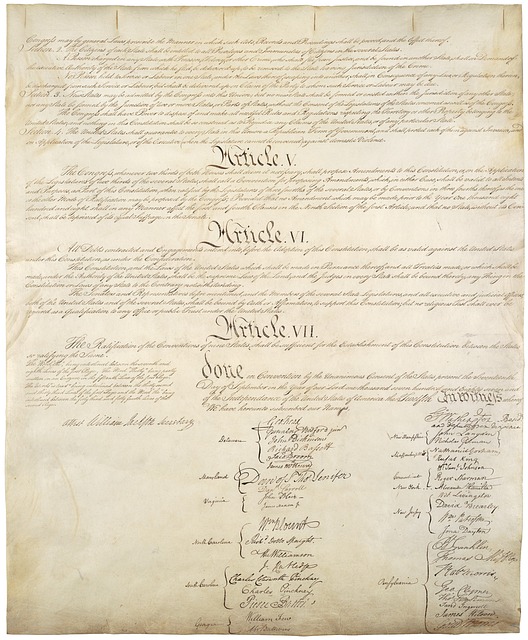

1. **The U.S. Constitution: Oldest and Shortest Written National Constitution Still in Use**It might surprise many to learn that of all the written national constitutions across the globe, the U.S. Constitution holds a unique distinction: it is both the oldest and one of the shortest still actively governing a nation. This remarkable document, signed in 1787, has shaped American history and governance for over two centuries, demonstrating an unparalleled longevity in constitutional law.

While some countries like the UK and San Marino may boast constitutional traditions that predate the American experiment, the U.S. Constitution is specifically recognized as the oldest *codified* constitution in continuous use. Its signing on September 17, 1787, marked a pivotal moment, with its principles going into effect on March 4, 1789. This two-century lifespan is a testament to the foresight of its framers and its inherent adaptability.

Equally striking is its brevity. Ever wondered how many words it contains? Just 4,543, including the signatures that solidified its creation. This conciseness, especially when compared to the often-voluminous constitutions of other nations, is a defining characteristic. This succinctness has allowed for flexibility and interpretation, enabling the document to evolve and remain pertinent through dramatic societal transformations.

This combination of age and brevity speaks volumes about its foundational strength. Its general language has provided the necessary space for reinterpretation and adaptation over the centuries, proving its resilience. It ensures that while the core principles endure, their application can respond to modern challenges, a true testament to its lasting impact.

2. **Forged in Secrecy: Behind Locked Doors and Guarded Sentries**The creation of the United States Constitution was not a public spectacle, but rather an intensely private affair. The document was prepared in secret, behind locked doors that were guarded by sentries, ensuring that the deliberations of the Constitutional Convention remained entirely confidential. This level of secrecy was a deliberate choice made by the delegates in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787.

The primary reason for this strict confidentiality was to encourage delegates to speak their minds freely and honestly, without fear of public pressure, scrutiny, or political repercussions. The context explicitly states that delegates were ordered “not to share any convention deliberations with the public. They had to keep all records of the event a secret for 30 years, and this was done to encourage the delegates to share their opinions without any fear.” This created an environment conducive to robust debate and, crucially, to the difficult compromises necessary to forge a new government.

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the same Pennsylvania State House where the Declaration of Independence had been signed just eleven years prior. This historical setting witnessed four months of intense drafting, from May to September 1787, all shielded from public view. This period of quiet, intense deliberation underscores the profound significance the framers placed on creating a stable and lasting framework for the nation, free from external distractions and premature judgments.

3. **The Original Omission: A Constitution Without a Bill of Rights**Perhaps one of the most surprising facts about the U.S. Constitution is that the original document, as signed in 1787, did not include a Bill of Rights. This foundational list of individual liberties, which Americans now consider indispensable, was not an initial part of the supreme law of the land. This omission was a significant point of contention and a major source of concern for many early American leaders.

“Some of the original framers and many delegates in the state ratifying conventions were very troubled that the original Constitution lacked a description of individual rights.” The absence of explicit protections for personal freedoms quickly became a rallying cry for those who feared a powerful federal government. These individuals, often referred to as Anti-Federalists, argued that without a Bill of Rights, the government could potentially infringe upon the liberties of citizens.

The inclusion of a Bill of Rights became a critical condition for the Constitution’s ratification in many states. It was essentially a promise made by the Federalists to secure the necessary approval. As the context notes, “Because ratification in many states was contingent on the promised addition of a Bill of Rights, Congress proposed 12 amendments in September 1789.” This promise was crucial to bridging the divide between proponents and opponents of the new Constitution.

Ultimately, this commitment led to the addition of the first ten amendments, which were ratified in 1791 and became known as The Bill of Rights. James Madison played a pivotal role in this process, proposing its inclusion in June 1789 after the Constitution had been approved. He meticulously trimmed various proposed rights, leaving only the essential ones for consideration by Congress, ensuring that these fundamental protections for citizens were formally enshrined in the nation’s governing document.

4. **Notable Absences: When Key Founding Fathers Missed the Convention**When we envision the Constitutional Convention, we often picture a room filled with all the celebrated figures of America’s founding era. However, a little-known fact is that some of the most prominent Founding Fathers were notably absent from the deliberations in Philadelphia. Their absence was not due to indifference, but rather pressing duties that placed them far from the momentous proceedings.

“Two of America’s Founding Fathers didn’t sign the Constitution.” Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, both instrumental in shaping the early republic, were not present to contribute to the drafting or to sign the final document. At the time, they were serving the nascent United States in crucial diplomatic capacities abroad, representing their country on the international stage during a critical period.

Thomas Jefferson was assigned diplomatic duties to France, where he served as the U.S. ambassador. His time in France was significant, and he would later negotiate the Louisiana Purchase, a monumental expansion of the young nation. Meanwhile, John Adams was serving as the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, a post that required his full attention. Adams was a known proponent of checks and balances, principles that ultimately found their way into the Constitution despite his absence from the drafting table.

Their absence underscores the vast responsibilities and global engagement of the early American leadership. Beyond these two giants, other notable figures were also not present, including James Monroe, who was more focused on state governance at the time, and other significant revolutionary figures such as John Hancock, Samuel Adams, Richard Henry Lee, and Patrick Henry. The Convention, while gathering many brilliant minds, was not an all-encompassing assembly of every influential figure of the era.

5. **Principled Dissent: Why Some Delegates Refused to Sign**Even among the delegates who dedicated months to the intense debates of the Constitutional Convention, not all were convinced enough by the final draft to affix their names. Of the 55 delegates who initially attended, and the 42 who remained until the end, only 39 ultimately signed the Constitution. This means three delegates, present for the crucial moments of its creation, made a principled decision not to endorse the document.

These three individuals were Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, Edmund Randolph of Virginia, and George Mason of Virginia. Their reason for dissatisfaction was clear and potent: the Constitution, in its original form, did not include a Bill of Rights. They were deeply concerned that without explicit protections for individual liberties, the new federal government would possess too much power and potentially infringe upon the rights of citizens.

Their dissent was not a trivial matter. George Mason, in particular, was a strong advocate for a declaration of rights, and his refusal to sign highlighted a fundamental disagreement that echoed across the nascent nation. This concern was not an isolated sentiment; it galvanized the Anti-Federalist movement during the subsequent ratification debates, demonstrating the deep philosophical divides that shaped the American political landscape.

This principled stand by Gerry, Randolph, and Mason underscored the crucial importance of securing individual rights in the minds of many Americans. Their decision to withhold their signatures, rather than being a mark of opposition to the idea of a stronger union, served as a powerful catalyst. It ultimately led to the later addition of the Bill of Rights, fulfilling the promise that was essential for many states to ratify the Constitution and establishing a cornerstone of American civil liberties.

6. **A Republic, Not a Democracy: The Founders’ Deliberate Choice**One of the most surprising and often misunderstood facts about the U.S. Constitution is the deliberate absence of the word “democracy” within its text. While the United States is frequently referred to as a democracy today, the Constitution itself establishes America as a federal republic. This distinction was not an oversight but a conscious and carefully considered choice by the Founding Fathers.

The framers held a profound skepticism towards direct democracy, fearing what they termed “mob rule.” They believed that a pure democracy, where every citizen directly voted on every issue, could lead to instability, impulsiveness, and the tyranny of the majority over minority rights. Their experiences and studies of historical governments, including the Athenian system, led them to conclude that such a model would be a dangerous way to govern a nation as vast and diverse as the emerging United States.

Consequently, they opted for a republican form of government. In a republic, the people do not govern directly but instead elect representatives to make decisions on their behalf. As the context explains, they decided “to make the US a republic where the people in various states will appoint representatives to represent them in Congress and also pass laws that will favor and protect the rights of the people.” This system was designed to temper popular will with deliberation and to protect individual liberties from the potential excesses of direct popular sentiment.

This choice also drew inspiration from historical models like the Athenian government, which, while influential, was carefully adapted. While ancient Greece saw citizens having a direct say through public votes, the United States diverged by having the people elect representatives. This emphasis on representation, rather than direct participation in every government affair, was a critical element of their vision, establishing a balanced and enduring structure for the nation.

7. **The Great Compromise: Forging a Bicameral Legislature**The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was rife with intense disagreements, particularly over the fundamental question of how states should be represented in the new federal legislature. This issue pitted larger states against smaller ones, each advocating for a system that would best serve their interests and populations. The debates were often described as “rancorous” and threatened to derail the entire process of forging a stronger union, demanding a solution that could unify disparate perspectives.

Smaller states, like New Jersey, championed a system where all states would have equal representation, regardless of population size. This proposal, known as the New Jersey Plan, echoed the structure of the existing Articles of Confederation, which granted each state one vote. Their fear was that a population-based system would allow larger states to dominate the national government and potentially infringe upon the sovereignty and interests of smaller polities, thereby undermining their influence.

Conversely, larger states, such as Virginia, put forth the Virginia Plan, advocating for proportional representation based on a state’s population. They argued that a government designed to represent the people should allocate legislative power according to the number of citizens, ensuring that more populous states had a greater say in national affairs. The stark contrast between these two proposals created a deep impasse that required ingenious and politically delicate solutions to move forward.

It was the Connecticut delegation, led by Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth, who ultimately offered the pivotal solution: “The Great Compromise.” This groundbreaking proposal resolved the bitter dispute by creating a bicameral legislature, meaning a two-chambered Congress. This system established a Senate, where all states would be equally represented with two senators each, satisfying the concerns of smaller states for equal footing. Simultaneously, it created a House of Representatives, where representation would be apportioned based on a state’s population, thus addressing the demands of larger states for proportional influence.

This ingenious compromise, also incorporating the contentious “three-fifths compromise” for counting enslaved populations in representation, was crucial for the successful drafting and eventual ratification of the Constitution. It demonstrated the framers’ capacity for negotiation and their commitment to finding a middle ground that could unite a diverse collection of states under a single, strong federal government. Without this pivotal agreement, the formation of the United States as we know it might have taken a dramatically different, or perhaps impossible, path.

8. **”We the People”: The Revolutionary Preamble and National Sovereignty**The opening words of the U.S. Constitution, “We the People,” are far more than just a ceremonial introduction; they represent a profound and revolutionary statement about the source of governmental authority. This crucial phrase serves as the preamble to the entire document, setting the stage for the framework of governance that follows. Its simplicity belies its powerful message, fundamentally shaping the nation’s understanding of sovereignty from its inception.

Historically, governing documents often derived their authority from monarchs, divine right, or a collection of sovereign states. The Articles of Confederation, for instance, specifically listed all the states as its framers, emphasizing state-level power. By contrast, the Constitution deliberately chose “We the People” to signify that the ultimate power and legitimacy of the government originated directly from the citizens of the United States, rather than from individual states or any external power. This was a radical departure from traditional political philosophy, asserting popular sovereignty.

This choice underscores a critical shift from a confederation of sovereign states to a national government deriving its power from the populace. It highlights that the Constitution itself, the federal government it establishes, and the laws enacted under it are all ultimately accountable to the American people. This concept of popular sovereignty provides the moral and legal foundation for the entire American experiment, ensuring that governance is by consent of the governed and rooted in the collective will.

The phrase “We the People” also implicitly rejects the “mixed regime” model prevalent in the British Empire, which blended monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic elements. Instead, it assigned all sovereignty to the citizens, reinforcing the idea of a unified nation built upon the collective will of its inhabitants. This enduring preamble continues to serve as a powerful reminder of who holds the ultimate authority in the United States, influencing constitutional interpretation and civic engagement to this day.

9. **The Constitution’s Enduring Adaptability: A Difficult Amendment Process**The U.S. Constitution is not merely a static relic of the past; it is a “living blueprint” that has demonstrated remarkable adaptability over centuries, primarily through its unique and deliberately challenging amendment process. This ability to evolve ensures that while the core principles endure, their application can respond to societal changes and modern challenges. It’s a testament to the framers’ foresight that they built in a mechanism for future generations to refine the document without resorting to wholesale replacement.

However, amending the Constitution is famously difficult, making it one of the least amended governing documents in the world. Since its official operation in 1789, only 27 amendments have been successfully ratified, despite “more than 11,000 amendments having been introduced in Congress.” This scarcity of amendments is not an accident; it’s a deliberate design to ensure that any changes reflect a broad and deep national consensus, preventing impulsive or transient political whims from altering the nation’s foundational law.

The process involves two laborious steps, making it incredibly rigorous. First, for an amendment to be proposed, it must secure a two-thirds vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Alternatively, two-thirds of the state legislatures can request Congress to call a national convention to propose amendments, though this method has never been successfully used. This high bar at the proposal stage ensures significant legislative backing before an idea even moves forward to the states for consideration.

The second step, ratification, is even more demanding. Once proposed, an amendment must be approved by three-fourths of all states. This can be achieved either through a vote by state legislatures or by state conventions, as determined by Congress. With 50 states currently, this means 38 states must ratify an amendment for it to become part of the Constitution. This dual requirement for supermajorities at both federal and state levels ensures widespread agreement and stability for the supreme law of the land, affirming its status as a robust and enduring framework.

10. **A Tale of Two Amendments: Prohibition, Repeal, and the 21st**Among the 27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution, a particularly fascinating and historically significant pair stands out: the 18th and 21st Amendments. These two amendments tell a compelling story of societal change, legislative experimentation, and the ultimate power of the people to correct a constitutional course. Their intertwined narrative offers a vivid illustration of the Constitution’s capacity for evolution and demonstrates that even fundamental policies can be revisited and reversed through the amendment process.

The 18th Amendment, ratified on January 16, 1919, marked a radical shift in American social policy by making “alcohol illegal.” This amendment ushered in the era of Prohibition, a nationwide ban on the production, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. Driven by moral and temperance movements, it was seen by many as a progressive step to improve public health and order. However, its implementation proved to be highly contentious and ultimately ineffective, leading to unforeseen consequences such as a rise in organized crime and widespread disrespect for the law across the nation.

After more than a decade of the “noble experiment” of Prohibition, public sentiment began to shift dramatically. The practical challenges of enforcement, coupled with economic factors during the Great Depression, led to a growing demand for the repeal of the 18th Amendment. This widespread dissatisfaction culminated in the proposal and swift ratification of the 21st Amendment, reflecting a clear change in national priorities and beliefs about personal liberty and government intervention.

The 21st Amendment, passed and ratified in 1933, holds a unique distinction: it is “the only amendment to repeal another amendment.” Its sole purpose was to nullify the 18th Amendment, effectively ending Prohibition and returning the regulation of alcohol to individual states. This act of repeal was a powerful demonstration of the American public’s ability to correct a constitutional path that was no longer aligned with national consensus, highlighting the dynamic nature of the Constitution and the role of its citizens in shaping its destiny.

11. **Rhode Island’s Rebellion: The Last Holdout for Ratification**The ratification of the U.S. Constitution was by no means a foregone conclusion; it was a contentious battle fought fiercely in each of the thirteen states. While many states quickly moved to approve the new framework, one state, in particular, stood out for its staunch opposition and prolonged resistance: Rhode Island. Its journey to ratification highlights the deep philosophical divides and the strong desire for state sovereignty that characterized the early American republic, showcasing the intense political landscape of the era.

Rhode Island had distinct reasons for its skepticism. Under the Articles of Confederation, the country’s first constitution, states held significant power, and the federal government had limited authority. Rhode Island, in particular, “enjoyed this power” and its ability to “collect taxes and use them per their discretion.” The proposed Constitution, with its stronger federal government and its power to “levy taxes,” was viewed as a direct threat to this cherished state autonomy, sparking deep concern among its citizens and leaders.

Driven by these fears of an overreaching federal power and a potential loss of their state’s sovereignty, Rhode Island took the extraordinary step of boycotting the Constitutional Convention altogether. They refused to send delegates to Philadelphia, signaling their deep distrust of the proposed changes. This absence during the drafting process underscored their commitment to a decentralized government structure and their apprehension about uniting under a more powerful central authority, highlighting their independent spirit.

Even after the new Constitution was signed on September 17, 1787, and sent to the various states for ratification, Rhode Island continued its resistance. It became “the last of the original thirteen states to ratify it,” holding out until 1790 after enduring “11 ratification conventions.” This prolonged battle reflects the intense debates between Federalists and Anti-Federalists within the state and across the nation, showcasing the immense political will and persuasion required to transition from a loose confederation to a more unified federal republic.

12. **Global Inspiration: The Constitution’s Far-Reaching Influence**Beyond its profound impact on American governance, the U.S. Constitution has achieved a remarkable status as a global blueprint for democratic principles and constitutional law. Its innovative framework, designed to balance governmental power with individual liberties, has resonated across continents and centuries, inspiring nations far beyond its shores. This enduring legacy solidifies its place not just as a national treasure but as a significant document in world history, demonstrating its universal appeal and applicability.

The framers drew heavily from historical documents and philosophies, such as the Magna Carta, John Locke’s writings on natural rights, and Montesquieu’s ideas on the separation of powers. In turn, these principles, enshrined in the American Constitution, became a wellspring of inspiration for subsequent constitutional movements worldwide. Its emphasis on a written, codified constitution, establishing a clear framework for government and rights, offered a tangible model for emerging nations seeking to establish stable, representative governance.

One notable early example of this influence is the French Constitution of 1791, which was “influenced by the U.S. Constitution” during its own revolutionary period, as it sought to establish a new order after its monarchy. Later, in the 20th century, following World War II, the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947, was ” heavily influenced by the U.S. Constitution,” particularly in its structure of government and its commitment to fundamental rights, reflecting a post-war reshaping of its political system.

Furthermore, “many Latin American countries have adopted similar constitutional frameworks,” demonstrating a broader regional adoption of its core tenets. From the separation of powers and the system of checks and balances to the inclusion of a Bill of Rights, the U.S. Constitution has served as a powerful example of how a nation can establish a stable, representative government while protecting the freedoms of its citizens. Its status as the “oldest written national constitution still in use” underscores its resilience and its continuing role as a guiding star for democratic governance globally.

As we reflect on these fascinating facts, it becomes clear that the U.S. Constitution is far more than an antiquated document. It is a testament to the power of deliberate compromise, a safeguard for individual liberties, and a dynamic framework that has continually adapted to the evolving needs of a nation. Its unique features, the arduous battles over its ratification, and its ongoing evolution through amendments have crafted a resilient charter that continues to shape our daily lives, ensuring that its foundational principles remain relevant for generations to come. Understanding these intricate details empowers us all to engage more deeply with the bedrock of American democracy, appreciating its past and contributing to its future.