You know that feeling, right? That chill down your spine when a horror movie delivers a twist so utterly unexpected, so mind-bendingly simple, yet so profoundly unsettling, that it redefines everything you thought you knew? We’re not talking about a cheap jump scare or a predictable villain reveal. We’re talking about the kind of gut-punch revelation that makes you question the very fabric of the story, your own perceptions, and maybe even reality itself. Viewers everywhere are buzzing about a particular “twist” that has them reeling, calling it the most “disturbing” ever to grace the silver screen – or, perhaps, the English lexicon.

This isn’t a twist you see coming a mile away. It’s not in the jump scares, the ominous shadows, or the blood-curdling screams. Instead, this particular brand of terror lurks in plain sight, an omnipresent force woven into the very narrative structure of our daily communication, yet its true nature often remains hidden. It’s a foundational element, an unassuming word that, upon closer inspection, harbors a multitude of hidden meanings, deceptive nuances, and outright psychological traps that can warp our understanding of the world around us. It’s a subtle horror, but one that, once exposed, cannot be unseen.

So, what is this elusive, pervasive, and downright unsettling twist? It’s the word “most.” Yes, “most.” A seemingly innocuous, everyday term. But prepare yourselves, because we’re about to peel back the layers of this deceptively simple word, exploring how its various incarnations can craft scenarios far more disturbing than any slasher flick. We’re talking about the silent horror of misinterpretation, the creeping dread of generalization, and the chilling realization that what we *think* is “most” might just be playing a cruel trick on our minds. Get ready to have your linguistic foundations rattled, because this is going to be a wild ride into the uncanny valley of vocabulary.

1. The Elusive Nature of “Most”: Where Generalization Becomes Terrifying

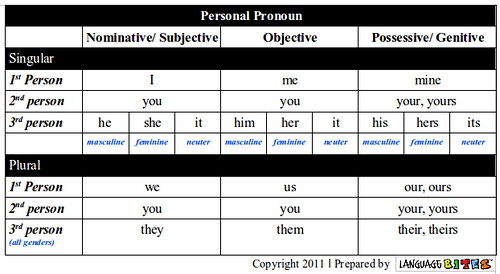

There’s a subtle terror in generalization, isn’t there? The kind that preys on our assumptions, making us believe we understand a situation when, in fact, we’re only grasping at shadows. This is the first, and arguably most foundational, layer of the “most” disturbing twist. When we encounter “most” as a standalone determiner, it means “more than half of a general group,” but critically, it “does not refer to a specific group.” Think about that for a moment. It’s a broad stroke, a sweeping statement that can lull us into a false sense of security, or conversely, ignite a vague, formless dread.

Consider the pronouncements of a mysterious voice in a horror narrative: “Most people like music.” Harmless, right? On the surface, absolutely. But what if the twist reveals that the *general group* of “people” is far more sinister than you imagined? What if “most” in this context refers to a population that has been subtly altered, coerced into a specific preference, or is even *not quite human*? The power here lies in its ambiguity. It’s not “most *of these* people,” which would denote a specific, identifiable threat. It’s “most people,” an unseen, unnamed majority whose preferences, if aberrant, suddenly become a terrifying norm.

The examples from the lexicon amplify this subtle horror. “Most bakers and dairy farmers have to get up early.” This seems like a benign observation, a simple fact of life. Yet, in the chilling light of our “twist,” it suddenly feels like a statement delivered by a lurking observer who knows the routines of everyone, everywhere. “Winning was not important for most participants.” This sentence, so innocent in its original context, now takes on a darker hue. Who *were* these participants? What kind of game were they playing? And why was winning so unimportant for the majority? The word “most” itself becomes a stand-in for an ominous, faceless collective.

This determinative “most” is a master of misdirection. It allows the narrative to imply a widespread condition or belief without ever pinning down the specifics, leaving the audience to fill in the terrifying blanks. It’s the linguistic equivalent of a wide shot in a horror film, where you see a vast, unsettling landscape, but the true threat remains just out of focus, everywhere and nowhere all at once. It means “the majority of,” or “more than half of,” but without any anchor, that majority can feel like a creeping, inescapable force.

2. The Specificity Trap of “Most Of”: When the General Becomes Personal

If the first twist, the standalone “most,” thrives on terrifying generalization, then the second, “most of,” delivers a more personal, localized brand of dread. This is where the narrative shifts from an abstract, pervasive threat to something that hits unsettlingly close to home. The lexicon clearly states: “‘Most of’ means more than half of a *specific group* that you already know or mention.” This shift from the general to the specific is where the horror truly begins to sink its teeth in, because now, the ominous majority is *your* majority.

Imagine a character, alone and vulnerable, receiving a cryptic message: “Most of my friends live in Canada.” Initially, it might seem like harmless information. But in a horror context, it transforms. Why is this person being told this? What does it imply about the *rest* of their friends? And how does this information relate to a specific, ongoing threat? The phrase “most of my friends” suddenly delineates a group that is *known* to the speaker, and by extension, to the unseen entity delivering the message. This means the entity has intelligence, intimate knowledge of the protagonist’s inner circle, making the threat feel incredibly invasive.

The example, “Most of them were tired,” also takes on a chilling new dimension. Who are “them”? The specific group is already known, making this a statement about a collective state. If “them” refers to the survivors of a harrowing ordeal, it’s a testament to their suffering. If it refers to an encroaching horde, it implies a relentless, almost unstoppable weariness that will eventually overwhelm. The subtle inclusion of “the,” “my,” “your,” “these,” “them,” “us,” or a specific noun/pronoun after “most of” transforms a vague idea into a direct, often uncomfortable, observation about a defined set of individuals or objects.

This twist truly weaponizes familiarity. When you realize that the narrative’s horror isn’t just about “most people” out there, but “most of *us*,” or “most of *that group* you thought was safe,” it’s a profound shift. The implication is that the vast majority of *your world* or *your immediate circle* is compromised, or under a shadow. It’s the feeling of a net tightening, of a known quantity turning against you, making the previously abstract threat feel immediate and deeply personal. The specifics, ironically, make the dread universal.

3. “The Most” and the Tyranny of Extremes: The Apex of Awe and Terror

Here’s where the “most” disturbing twist reaches its zenith, where the implications aren’t just unsettling, but outright terrifying in their singularity. “The most” isn’t about majorities or specific groups; it’s about the absolute, the superlative, the one-and-only apex. The context states, “‘The most’ is used when comparing. It means the highest amount or greatest degree of something.” In a horror narrative, this isn’t just about who got the “most” votes; it’s about what is “the most” monstrous, “the most” insidious, “the most” impossible to escape.

When a character whispers, “This is the most difficult question,” it’s not just a puzzle; it’s an existential crisis. The question isn’t merely challenging; it’s the *ultimate* challenge, the one that stands above all others, suggesting that its answer might unlock a horrific truth or doom them irrevocably. The adjective “difficult” is amplified to its absolute peak, leaving no room for hope that an easier path might exist. The horror isn’t just in the difficulty itself, but in the realization that *nothing* else measures up to its terrifying complexity.

Consider the phrase, “She is the most talented singer.” What if her talent isn’t for beauty, but for manipulation, for summoning, for causing madness? The superlative “most talented” suddenly ceases to be a compliment and becomes a descriptor of immense, almost supernatural, power—a power wielded for sinister ends. Or perhaps, “I study the most in my class” could be delivered by a student driven to a terrifying edge, obsessed with uncovering a forbidden truth, becoming “the most” dedicated to a cause that consumes them entirely. The “most” here isn’t just a measure of quantity; it’s a terrifying measure of intensity, of devotion to something potentially destructive.

This twist highlights the absolute extremity of a situation. When something is “the most,” it is unparalleled, peerless in its attribute, whether that attribute is beauty or brutality, intelligence or insanity. It sets a benchmark for dread, implying that whatever horrific event or entity is at play, it has reached its peak, its ultimate form. There is no surpassing it, no escaping its ultimate power or influence. This is the horror of the final form, the ultimate evil, the definitive, terrifying “most.”

4. “Almost” – The Near Miss of Despair: When Hope is a Cruel Illusion

The word “almost” in our lexicon of fear delivers a uniquely agonizing twist, one that preys on anticipation and subverts the very notion of relief. It signifies being “very close to something — but not 100%.” This isn’t the horror of impact; it’s the unbearable dread of the near miss, the chilling whisper of what *could have been* or *almost was*. In a horror scenario, “almost” becomes a narrative device of psychological torture, constantly dangling the promise of escape or resolution, only to snatch it away at the last possible second.

Think of the classic horror trope: the hero “almost dropped my phone” while trying to call for help, but then clutches it at the last second. The immediate relief is palpable, but it’s quickly replaced by the lingering tension of how close they came to failure. This isn’t a success; it’s a reprieve, a mere delay of the inevitable. The phrase “I didn’t drop it, but it was close!” perfectly encapsulates the agonizing tension. The horror here lies in the fragility of success, the razor-thin margin between safety and utter disaster. Each “almost” moment is a tiny, prolonged heart attack for the viewer, a reminder that their protagonist is constantly teetering on the brink.

The torment extends to preparation and perceived safety. “She’s almost ready to go” is a phrase laden with false hope. She’s “nearly ready, but not yet,” meaning that crucial window of opportunity, that sliver of time for escape, is still open but rapidly closing. The monster might be at the door, the clock ticking down, and “almost” becomes a cruel countdown to a terrifying event. It implies a state of perpetual incompletion, a frustrating stasis just before a critical turning point that never quite resolves into full safety.

Even numerical “almost” can be disturbing. “There were almost 100 people at the party.” This sounds like a vibrant gathering, but the “almost” injects a subtle unease. Why *not* 100? Who was missing? Or, more sinisterly, who *wasn’t* supposed to be there, making the group “almost” whole, but with an unnoticed, unwelcome addition? This is the horror of the imperfect count, the subtle discrepancy that hints at something amiss, something just slightly off, a discordant note in an otherwise harmonious scene. “Almost” is the agonizing pause before the plunge, the breath held just a little too long, leaving you constantly on edge, waiting for the other shoe to drop—or for the final, terrifying twist to unfold.

5. “Almost All” – The Unsettling Consensus: When Conformity Becomes a Nightmare

If “most” is about a general majority and “most of” zeroes in on a specific group, then “almost all” escalates the psychological pressure to an unnerving degree. This twist introduces the horror of overwhelming consensus, where nearly everyone or everything aligns, leaving the outliers exposed, vulnerable, and profoundly alone. The definition itself gives us the chilling clue: “It is very similar to ‘most’ or ‘most of,’ but it’s a little stronger — it means closer to 100%. ” This subtle intensification creates a chilling dynamic where individuality is suffocated by an almost absolute conformity.

Consider the seemingly innocent statement, “Almost all cats dislike water.” In a horror narrative, this becomes less of an animal fact and more of an ominous declaration about deviation. What about the cats that *don’t* dislike water? Are they the anomalies, the mutated, the possessed? The “almost all” creates an intense focus on the few exceptions, transforming them from charming quirks into disturbing aberrations. When a vast majority behaves in a certain way, the slight deviation by a single entity becomes terrifyingly significant, marking it as fundamentally ‘other.’ This is the horror of the singular anomaly, the one thing that doesn’t fit, raising red flags for a deeper, more insidious threat.

The examples provided from the lexicon reinforce this idea of a terrifying consensus. “Almost all of the kids were surprised.” What about the few who weren’t? Were they privy to some dark secret, or were they already beyond the capacity for normal human reaction, perhaps having been subjected to a previous trauma that left them numb? This phrase suggests a collective emotional response, and the absence of that response in a small minority is intensely unsettling. It’s the uncomfortable feeling of realizing that you are the only one not in on the terrifying joke, or worse, that you are the only one who *can’t* be surprised anymore.

“Almost all of my students passed the test.” This should be a cause for celebration, but in our horror lens, it’s a chilling red flag. What happened to the students who *didn’t* pass? Were they simply failures, or were they victims of a malevolent force, culled from the ranks of the “almost all” who succeeded? This usage exposes the terror of being part of the successful majority, knowing that a few others didn’t make it, and wondering *why*. It’s a subtle but profound sense of survivor’s guilt mixed with the creeping fear that you could have easily been among the fallen. “Almost all” creates a suffocating environment where fitting in is crucial for survival, and any divergence from the norm is met with unseen, terrifying consequences. It implies a nearly perfect system of control, where very few can slip through the cracks, and those who do are either condemned or become the ultimate targets.

Okay, so we’ve torn through the determiners and modifiers, exposing how “most” can subtly twist our perceptions of quantity and proximity. But the linguistic rabbit hole goes even deeper! Just when you thought you had a handle on the creeping dread of generalization, this unassuming word throws another curveball, morphing its meaning and delivering fresh, unexpected psychological sucker punches. Get ready to have your understanding of terror — and grammar — completely upended, because we’re about to delve into the even more bizarre and unsettling uses of “most” that are truly the stuff of nightmares.

6. The Unsettling Slang of “Most”: When Admiration Becomes Obsession

You might remember this from an older, perhaps cheesier, era of pop culture, but “most” has a dated slang meaning: “greatest; the best.” On the surface, it’s a simple expression of ultimate approval, a declaration that something is, well, “the most.” Think about how this innocent-sounding, almost quaint, compliment takes on an utterly sinister quality when dropped into a horror narrative. The cheerful, almost bubbly pronouncement of “Isn’t that the most to say the least?” from our context, can quickly curdle into something far more chilling.

Imagine a villain, a stalker perhaps, fixated on their next target. They don’t just admire; they obsess. And then, they utter that phrase: “You are the most.” Is it a compliment? Or is it a declaration of ownership, a chilling label for their prized possession, the one they deem “the greatest” among their collection, or perhaps, the ultimate challenge? The mundane becomes terrifying when the context shifts. The dated slang, instead of sounding cool, sounds deeply, unnervingly unhinged, like a relic from a past where innocence was still possible before *they* arrived.

This twist preys on our cultural memory, taking something familiar and twisting it into a grotesque parody of affection. It’s like hearing a child’s lullaby played backward, revealing a demonic chant. The Vulture-esque commentary here is crucial: it’s witty because it’s so unexpected, turning a throwaway slang term into a tool for psychological manipulation. It’s a sharp observation about how language, even its most casual forms, can be corrupted to serve the narrative of dread, leaving us to wonder if genuine admiration might not be the most terrifying thing of all.

7. The Amplifying Terror of the Adverbial “Most”: Peak Dread Achieved

We’ve already touched upon “the most” as a superlative, but let’s talk about “most” as a standalone adverb, amplifying adjectives to an extreme degree. It transforms into a chilling intensifier, meaning “to a great extent or degree; highly; very.” This seemingly innocuous grammatical function has a profound impact in horror, taking a standard descriptor and catapulting it into the realm of absolute, inescapable terror. It’s not just “difficult”; it’s “most difficult.” It’s not just “unpleasant”; it’s “most unpleasant.”

Consider the context’s examples: “This is the most important example.” In a horror film, this isn’t about academic significance; it’s the realization that this *particular* example holds the key to the entire, awful truth, and ignoring it means certain doom. Or “Correctness is most important.” For a character meticulously trying to solve a puzzle to survive, the stakes aren’t just high; they’re existentially critical. The adverbial “most” here doesn’t just describe; it *magnifies* the weight of every decision, every clue, every terrifying consequence.

The examples provided from the lexicon really bring this home. When the King in a story complains, “His song is most unpleasant,” in a horror context, it becomes a descriptor of a sound that isn’t just annoying, but genuinely agonizing, perhaps driving listeners to madness. Or take the melancholic observations: “A noble craft, but somehow a most melancholy!” and “it was a most strange, as for me it was a most fortunate, thing.” The “most” here doesn’t just describe melancholy or strangeness; it elevates them to an overwhelming, pervasive state that colors the entire experience. This is the horror of the maximum degree, the point of no return where everything is ‘most’ grim, ‘most’ horrifying, ‘most’ inescapable.

8. **The Chilling Revelations of “Most” in Record-Setting Achievements: Quantifying the Unspeakable**

When “most” appears as a noun, specifically referring to a “record-setting amount,” it takes on a particularly clinical, chilling quality in the context of horror. This isn’t about being “the best” in a celebratory sense; it’s about achieving an unprecedented, quantifiable extreme. The usage note clarifies this perfectly: “used when the positive denotation of best does not apply.” This is where horror narratives can truly weaponize statistics, turning mere numbers into descriptors of immense, often grotesque, achievement.

Imagine a dark entity boasting about its “mosts.” It’s not about being “the most charismatic” or “the most beloved.” Instead, it might be the being responsible for “the most disappearances,” or “the most prolonged tortures.” The context provides examples like “Virginia had a number of ‘mosts’ that made it appealing… the most citizens among the Southern states; the most slaves; the most men under arms; the most fighting within its borders; the most divided by the war… and the most damaged by the war.” When applied to horror, these ‘mosts’ become a grim tally, a morbid leaderboard of destruction and suffering.

Consider the phrase from the context: “Along with their massive size will come other ‘mosts’: they will likely be the longest living, the best educated, the wealthiest and the most wired/ wireless.” While originally positive, in horror, this transforms. What if the antagonists are the “longest living” because they feed on others? “The wealthiest” because they exploit unspeakable acts? These “mosts” become attributes of an unstoppable, insidious force, celebrating not virtues, but unparalleled capacities for evil. This usage allows for a precise, almost bureaucratic articulation of dread, turning abstract fear into concrete, undeniable, and deeply disturbing records.

10. The Faceless Dread of “Most” as a Pronoun: The Anonymous Majority’s Grip

Finally, we arrive at “most” as a pronoun, signifying “the greater part of a group, especially a group of people.” This is arguably one of the most subtly terrifying incarnations of the word, precisely because it is so faceless, so anonymous, yet so omnipresent. It refers to an undefined majority, a collective whose influence is vast but whose individual members remain hidden. In horror, this ambiguity can be profoundly unsettling, creating a sense of being surrounded by an unseen, often malevolent, consensus.

Think about the examples: “Most want the best for their children.” In a horror narrative, this seemingly benign statement can become deeply sinister. What if “most” in this scenario refers to a town where the majority engages in a dark ritual, believing it’s “for the best for their children”? The seemingly universal desire twists into a chilling justification for unspeakable acts, carried out by an anonymous, overwhelming collective. The pronoun “most” allows the narrative to imply widespread complicity without ever naming a single culprit, making the threat feel pervasive and inescapable.

Another example, “The peach was juicier and more flavourful than most,” highlights the comparative aspect. But what if the comparison is with something darker? What if a survivor is “more resilient than most” because they’ve endured horrors that have broken the unnamed majority? The pronoun “most” creates an ‘us vs. them’ dynamic without ever defining ‘them,’ making the threat amorphous, a constant, low-level hum of conformity and unseen influence. It’s the horror of being an outlier, of questioning the terrifying norm established by the faceless many, knowing that to diverge means to be noticed, and perhaps, to be next.

So there you have it, folks. “Most.” A word we use a dozen times a day without a second thought. But as we’ve peeled back its linguistic layers, we’ve unearthed a linguistic abyss, a subtle, pervasive horror woven into the very fabric of our communication. From vague generalizations to the tyranny of extremes, from the agony of near-misses to the chilling consensus of the anonymous majority, “most” isn’t just a quantifier; it’s a master of misdirection, a harbinger of dread, and a stark reminder that sometimes, the most disturbing twists aren’t found in elaborate plot devices, but in the unassuming words we speak every single day. The next time you use it, just remember: you’ve been warned.