California, a state nestled in the Western United States along the Pacific Coast, stands as a testament to unparalleled diversity—geographical, cultural, and economic. Encompassing an expansive area of 163,696 square miles (423,970 km2), it holds the distinction of being the third-largest state by area. With an almost 40 million residents, it is the nation’s largest state by population, a vibrant mosaic of communities from its bustling metropolitan hubs to its serene natural wonders.

Its borders trace paths with Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and an international frontier with the Mexican state of Baja California to the south, forming a crucial part of the broader Californias region of North America. This geographic positioning has profoundly shaped its historical trajectory and continues to define its multifaceted character. California’s narrative is one of constant evolution, marked by discovery, conflict, growth, and innovation.

The very name “California” itself is steeped in a rich tapestry of myth and early exploration, a captivating detail that sets the stage for its unique story. The word and its legendary namesake, Queen Calafia, are first encountered in the 1510 epic, *Las Sergas de Esplandián*, penned by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. This literary origin tells of a mythical island, a remote land brimming with gold and pearls, inhabited by beautiful dark-skinned women who adorned themselves in gold armor, living akin to Amazons, alongside fantastical creatures like griffins.

Spanish explorers and settlers, driven by ambition and curiosity, initially bestowed the name *Las Californias* upon the peninsula of Baja California. As their ventures expanded northward and inland, the region known as California steadily grew, eventually encompassing lands north of the peninsula, which came to be known as Alta California. A portion of this expansive territory would later evolve into the present-day U.S. state, forever linked to a fictional queen and her golden kingdom.

While numerous theories about the origin and meaning of “California” persist, a 2017 state legislative document succinctly notes that all definitively known is that the name was inscribed on a map by 1541, “presumably by a Spanish navigator.” This lingering mystery only adds to the allure of a state born from both geographical reality and imaginative lore, a duality that continues to define its spirit.

Before the arrival of European explorers, California was a realm of extraordinary cultural and linguistic diversity, recognized as one of the most varied areas in pre-Columbian North America. Historians generally concur that at least 300,000 individuals resided in California before European colonization, representing more than 70 distinct ethnic groups. These indigenous peoples inhabited a vast array of environments, from towering mountains and arid deserts to isolated islands and majestic redwood forests.

Adapting to these diverse landscapes, the indigenous communities developed sophisticated forms of ecosystem management. This included forest gardening, a practice that ensured the regular availability of essential food and medicinal plants, embodying a form of sustainable agriculture. To mitigate the devastating impact of large wildfires, indigenous peoples masterfully developed and implemented a practice of controlled burning, a foresightful technique whose benefits were officially acknowledged by the California government as recently as 2022.

Their societal structures were equally diverse, encompassing bands, tribes, and villages, alongside large chiefdoms like the Chumash, Pomo, and Salinan, particularly prevalent in resource-rich coastal areas. Trade networks, intermarriage, the specialization of crafts, and military alliances all contributed to robust social and economic relationships among these varied groups. While conflicts occasionally arose, these small-scale battles primarily revolved around vengeance among groups of men, rarely with the aim of acquiring territory.

Within these societies, men and women generally fulfilled distinct yet complementary roles. Women often bore the responsibilities of weaving, harvesting, processing, and preparing food, while men typically engaged in hunting and other physically demanding labor. Intriguingly, most indigenous societies also recognized and embraced roles for individuals whom the Spanish referred to as *joyas*, perceived by them as “men who dressed as women.” These *joyas*, or “two-spirit” individuals, as many indigenous societies termed them, held significant societal functions, including presiding over death, burial, and mourning rituals, and performing social roles traditionally associated with women. The Chumash, for instance, referred to them as ‘aqi. Tragically, these integral figures were detested and targeted for elimination by the early Spanish settlers, a somber note in the state’s early history.

The Spanish period in California commenced with the maritime expedition of Portuguese captain Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542, commissioned by Antonio de Mendoza, the Viceroy of New Spain. Their search for trade opportunities led them into San Diego Bay on September 28, 1542, and as far north as San Miguel Island. Later, in 1579, privateer Francis Drake explored and laid claim to an unspecified segment of the California coast, landing north of the future city of San Francisco. A notable historical footnote marks 1587 as the year Filipino sailors, aboard Spanish ships, became the first Asians to set foot on what would become the United States, arriving at Morro Bay.

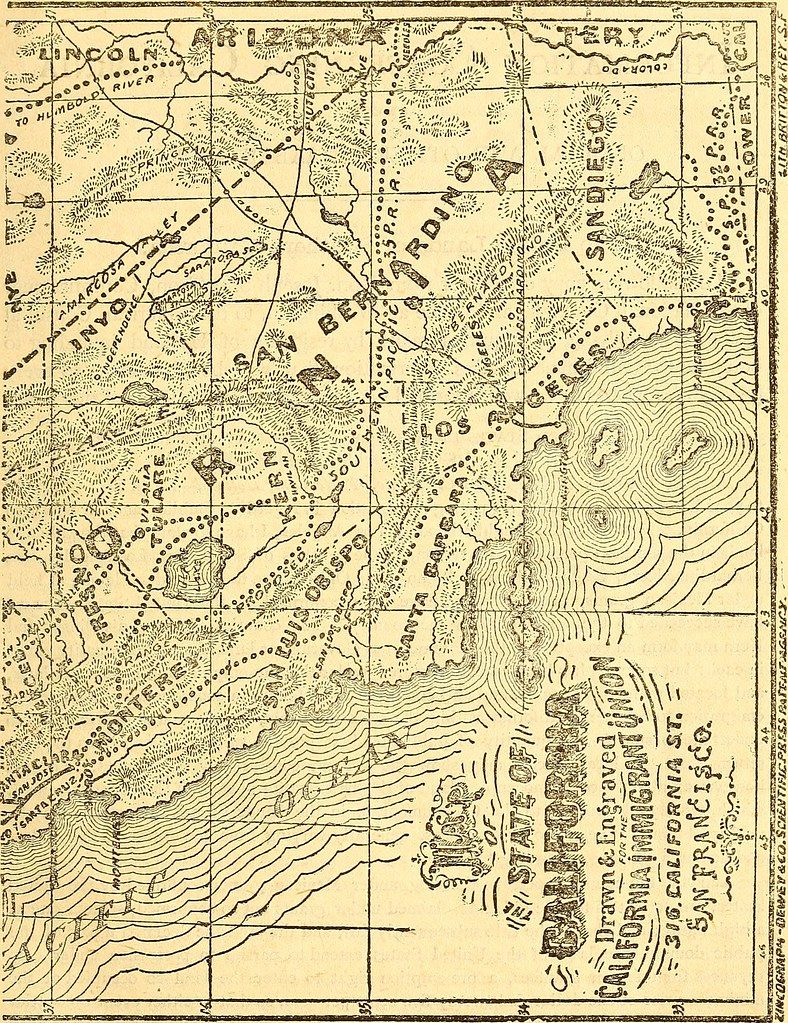

Sebastián Vizcaíno further explored and meticulously mapped the California coast in 1602 for New Spain, making landfall in Monterey. Despite these on-the-ground explorations throughout the 16th century, the enduring perception of California as an island, as posited by Rodríguez, remarkably persisted, appearing on numerous European maps well into the 18th century, a testament to the blend of fact and fantasy in early cartography.

A truly pivotal moment in Spanish colonization arrived with the Portolá expedition of 1769–70, leading to the foundational establishment of numerous missions, presidios, and pueblos. Gaspar de Portolá led the military and civil components overland from Sonora, while Junípero Serra, the religious leader, arrived by sea from Baja California. Together, in 1769, they founded Mission San Diego de Alcalá and the Presidio of San Diego, marking the Spanish’s inaugural religious and military settlements in California. By the expedition’s conclusion in 1770, they had also established the Presidio of Monterey and Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo on Monterey Bay.

Following the Portolá expedition, Father-President Serra and his missionaries embarked on a remarkable endeavor, establishing 21 Spanish missions along El Camino Real (“The Royal Road”) and the California coast, with 16 sites chosen during the initial expedition. Many of California’s most significant cities owe their origins to these missions, including San Francisco (Mission San Francisco de Asís), San Diego (Mission San Diego de Alcalá), Ventura (Mission San Buenaventura), and Santa Barbara (Mission Santa Barbara), among others, forming a spiritual and administrative backbone for the burgeoning colonial presence.

Another expedition of immense importance was led by Juan Bautista de Anza in 1775–76, venturing deeper into California’s interior and northward. This expedition identified numerous strategic sites for future missions, presidios, and pueblos, which subsequent settlers would establish. Gabriel Moraga, a member of this expedition, also holds the distinction of christening many of California’s prominent rivers with their lasting names between 1775 and 1776, including the Sacramento River and the San Joaquin River. Shortly after, Gabriel’s son, José Joaquín Moraga, founded the pueblo of San Jose in 1777, marking it as California’s first civilian-established city.

During this vibrant period of Spanish expansion, sailors from the Russian Empire also explored California’s northern coast. In 1812, the Russian-American Company established a trading post and a small fortification at Fort Ross on the North Coast, primarily to supply Russia’s Alaskan colonies with provisions. However, this settlement ultimately proved unsuccessful in attracting settlers or establishing long-term trade viability, leading to its abandonment by 1841.

The War of Mexican Independence largely bypassed Alta California, leaving it unaffected and uninvolved in the main revolutionary conflict. Nevertheless, many Californios expressed support for independence from Spain, feeling that Spain had neglected California and stunted its development. The dismantling of Spain’s trade monopoly on California following Mexican independence opened California’s ports to trade with foreign merchants, an economic liberation that paved the way for new opportunities. Governor Pablo Vicente de Solá oversaw this pivotal transition from Spanish colonial rule to independent Mexican governance, ushering in a new era for the region.

With the successful conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence in 1821, the Mexican Empire, which included California, gained its freedom from Spain. For the ensuing 25 years, Alta California existed as a remote, sparsely populated, northwestern administrative district of the newly independent country of Mexico, which soon transformed into a republic. A significant change occurred by 1834 when the missions, which had controlled much of the state’s prime land, were secularized and became the property of the Mexican government. The governor subsequently granted vast square leagues of land to individuals with political influence, giving rise to enormous *ranchos* or cattle ranches that became the dominant institutions of Mexican California. These *ranchos*, under the ownership of Californios (Hispanics native to California), primarily traded cowhides and tallow with Boston merchants, with beef only becoming a significant commodity after the 1849 California Gold Rush.

From the 1820s onwards, a steady stream of trappers and settlers from the United States and Canada began arriving in Northern California, utilizing trails such as the Siskiyou Trail, California Trail, Oregon Trail, and Old Spanish Trail to navigate the formidable mountains and harsh deserts. The nascent government of independent Mexico proved highly unstable, a reflection of which was a series of armed disputes within California itself and with the central Mexican government, commencing in 1831. Amidst this tumultuous political landscape, Juan Bautista Alvarado skillfully secured the governorship from 1836 to 1842. The military action that initially brought Alvarado to power had briefly declared California an independent state, notably aided by Anglo-American residents, including Isaac Graham. However, in 1840, the arrest of one hundred such residents lacking passports led to the “Graham Affair,” a diplomatic incident partially resolved through the intervention of Royal Navy officials, underscoring the growing international interest in California.

John Marsh, one of California’s largest ranchers, played a crucial role in the shift towards American annexation. Frustrated by his inability to obtain justice against squatters through the Mexican courts, he became convinced that California’s destiny lay with the United States. Marsh embarked on an extensive letter-writing campaign, passionately extolling California’s climate, fertile soil, and other virtues, while also detailing the most effective routes for settlement—information that became widely known as “Marsh’s route.” His letters were widely circulated, reread, and published in newspapers across the country, effectively catalyzing the first organized wagon trains bound for California.

Marsh’s influence extended into political and military spheres. He became involved in a conflict between the deeply unpopular Mexican general, Manuel Micheltorena, and the California governor he had replaced, Juan Bautista Alvarado. At the Battle of Providencia near Los Angeles, Marsh’s persuasive intervention convinced both sides to abandon their fight, leading to Micheltorena’s defeat and the return of California-born Pío Pico to the governorship. These actions by Marsh undeniably paved the way for California’s eventual acquisition by the United States, a pivotal moment in its history.

The year 1846 marked a significant turning point with the Bear Flag Revolt, where a group of American settlers in and around Sonoma rebelled against Mexican rule. These rebels subsequently raised the iconic Bear Flag, featuring a bear, a star, a red stripe, and the words “California Republic,” at Sonoma. William B. Ide, the Republic’s sole president, played a central role in this revolt, which served as a direct prelude to the American military invasion of California, closely coordinated with nearby American military commanders, signaling the impending shift in sovereignty.

The California Republic itself was fleeting, a brief interlude preceding the outbreak of the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) in the very same year. Commodore John D. Sloat of the United States Navy initiated the U.S. military invasion of California, sailing into Monterey Bay in 1846, leading to Northern California’s capitulation to United States forces in less than a month. However, resistance persisted in Southern California, where Californios steadfastly opposed American forces, engaging in notable military encounters such as the Battle of San Pasqual and the Battle of Dominguez Rancho. Northern California also saw conflicts like the Battle of Olómpali and the Battle of Santa Clara.

Following a series of defensive battles in the south, the Treaty of Cahuenga was formally signed by the Californios on January 13, 1847, effectively securing a cessation of hostilities and establishing *de facto* American control over California. This treaty was a ceasefire that ultimately concluded the U.S. conquest of California, further solidifying the trajectory towards statehood. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, officially ended the Mexican-American War, leading to the annexation of the westernmost portion of the Mexican territory of Alta California, which soon became the American state of California.

The remainder of the old territory was subsequently subdivided into the new American Territories of Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah, while the even more sparsely populated and arid lower region of old Baja California remained under Mexican sovereignty. In 1846, the total settler population of what would become the American state of California was estimated at no more than 8,000, alongside approximately 100,000 Native Americans, a stark decline from the estimated 300,000 before Hispanic settlement in 1769. Just one week before the official American annexation of the area in 1848, a discovery of monumental significance occurred: gold in California.

This single event fundamentally reshaped both the state’s demographics and its burgeoning finances, forever altering its destiny. A massive wave of immigration ensued, as prospectors and miners poured into the region by the thousands. The population swelled dramatically with United States citizens, Europeans, Middle Easterners, Chinese, and other immigrants during the Great California Gold Rush. By 1850, when California applied for statehood, the settler population had soared to 100,000, and by 1854, over 300,000 settlers had arrived. The city of San Francisco, a direct beneficiary of this boom, witnessed its population skyrocket from a mere 500 in 1847 to a staggering 150,000 by 1870, illustrating the profound and rapid transformation of the era.

Under both Spanish and later Mexican rule, the seat of government for California had been located in Monterey from 1777 until 1845. Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of Alta California, briefly relocated the capital to Los Angeles in 1845. The United States consulate, notably, had also been established in Monterey, under the purview of Consul Thomas O. Larkin. In 1849, the state Constitutional Convention convened for the first time in Monterey, with one of its immediate priorities being the selection of a permanent location for the new state capital.

The initial full legislative sessions of the newly formed state were held in San Jose from 1850 to 1851. Subsequent locations for the capital included Vallejo (1852–1853) and nearby Benicia (1853–1854), though these sites ultimately proved inadequate for the burgeoning governmental needs. Since 1854, the capital has been firmly established in Sacramento, with only a brief interruption in 1862 when legislative sessions were temporarily moved to San Francisco due to severe flooding in Sacramento. Once its state constitution was finalized, California formally applied to the U.S. Congress for admission to statehood, a request granted on September 9, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850, making California a free state and designating September 9 a state holiday.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), California contributed significantly to the Union effort by sending vital gold shipments eastward to Washington. However, due to a substantial presence of pro-South sympathizers within the state, California was unable to muster full military regiments for direct service in the Union war effort. Nonetheless, several smaller military units within the Union army, such as the “California 100 Company,” were unofficially linked to the state, with the majority of their members hailing from California, reflecting the complex loyalties of the time.

At the moment of California’s admission into the Union, travel between the state and the rest of the continental United States was a formidable and perilous undertaking, demanding considerable time. This changed dramatically nineteen years later, and seven years after President Lincoln’s approval, with the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. This engineering marvel reduced the journey from the Eastern States to California to a mere week, fundamentally transforming connections and fostering further growth.

Much of California proved exceptionally well-suited for fruit cultivation and agriculture in general, laying the groundwork for its future as a global breadbasket. Vast expanses of wheat, other cereal crops, various vegetable crops, cotton, and an array of nut and fruit trees, including oranges in Southern California, began to flourish. This agricultural boom firmly established the foundation for the state’s prodigious agricultural output, concentrated in the fertile Central Valley and other productive regions, a legacy that continues to define its economic prowess.

In the nineteenth century, a substantial number of migrants from China embarked on journeys to California, drawn by the allure of the Gold Rush or the prospect of work. Despite the Chinese proving indispensable in the monumental task of constructing the transcontinental railroad from California to Utah, widespread perceived job competition fueled anti-Chinese riots across the state. This intense pressure from California ultimately contributed to the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which partially halted migration from China, a lamentable chapter in American immigration history that highlights the complex interplay of economic anxiety and racial prejudice.

A darker, yet crucial, aspect of California’s history involves what is now recognized as the California genocide, perpetrated against Indigenous Californians between 1846 and 1873 by U.S. government agents and private settlers. This period of violence resulted in at least 9,456 deaths, with some estimates reaching as high as 100,000 indigenous lives lost. Under prior Spanish and Mexican rule, California’s original native population had already suffered a precipitous decline, primarily due to Eurasian diseases against which they lacked natural immunity, leading to widespread depopulation.

Under its new American administration, California’s first governor, Peter Hardeman Burnett, instituted policies that have been unequivocally described as a state-sanctioned policy for the elimination of California’s indigenous people. In his Second Annual Message to the Legislature in 1851, Burnett chillingly announced, “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate the result with but painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power and wisdom of man to avert.” This statement laid bare a horrifying intent.

As was the case in other American states, indigenous peoples were forcibly dispossessed of their ancestral lands by American settlers—miners, ranchers, and farmers alike. Despite California’s admission into the American union as a free state, the “loitering or orphaned Indians” were *de facto* enslaved by their new Anglo-American masters under the 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians. One particularly egregious example of this legalized oppression was *de facto* slave auctions, approved by the Los Angeles City Council, which persisted for nearly two decades. The period was marked by numerous massacres where hundreds of indigenous people were killed by settlers, driven by the desire for land.

Between 1850 and 1860, the California state government allocated approximately $1.5 million—with some $250,000 of this reimbursed by the federal government—to hire militias. While ostensibly purposed for protecting settlers, these militias were responsible for perpetrating numerous massacres of indigenous people. Furthermore, indigenous populations were forcibly relocated to reservations and rancherias, often small, isolated, and lacking sufficient natural resources or governmental funding to adequately sustain the populations compelled to live on them. Consequently, settler colonialism wrought profound calamity for indigenous peoples. Several scholars and Native American activists, including Benjamin Madley and Ed Castillo, alongside the 40th Governor of California, Gavin Newsom, have explicitly characterized the actions of the California government during this period as genocide. Benjamin Madley estimates that between 1846 and 1873, between 9,492 and 16,092 indigenous people were killed, including an estimated 1,680 to 3,741 deaths directly attributed to the U.S. Army.

The 20th century ushered in another wave of migration to California, notably thousands of Japanese people. However, this was met with discriminatory legislation, as the state in 1913 passed the Alien Land Act, explicitly excluding Asian immigrants from owning land. During World War II, a dark chapter unfolded as Japanese Americans in California and elsewhere were unjustly interned in concentration camps. California officially apologized for this profound injustice in 2020, acknowledging the historical wrong.

Migration to California dramatically accelerated in the early 20th century, spurred by the completion of transcontinental highways such as the iconic Route 66. From 1900 to 1965, the state’s population burgeoned from fewer than one million to become the largest in the Union, a monumental demographic shift. By 1940, the Census Bureau reported California’s population as 6% Hispanic, 2.4% Asian, and 90% non-Hispanic white, reflecting the prevailing demographics of the era.

To accommodate this explosive population growth and meet its escalating needs, California embarked on ambitious engineering feats, constructing impressive infrastructure such as the California and Los Angeles Aqueducts, the Oroville and Shasta Dams, and the Bay and Golden Gate Bridges. In a visionary move to cultivate an efficient system of public education, the state government adopted the California Master Plan for Higher Education in 1960, laying the groundwork for its renowned university systems. In the early 20th century, Hollywood studios, like the venerable Paramount Pictures, played a pivotal role in transforming Hollywood into the undisputed world capital of film, simultaneously solidifying Los Angeles’s status as a global economic hub.

Attracted by the mild Mediterranean climate, affordable land, and the state’s remarkable geographical diversity, filmmakers flocked to California, establishing the groundbreaking studio system in Hollywood during the 1920s. During World War II, California emerged as a crucial industrial power, manufacturing 9% of all U.S. armaments, ranking third nationally behind New York and Michigan. Even more significantly, California easily secured the top position in the production of military ships, leveraging its drydock facilities in San Diego, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area. The wartime demand for labor led to a massive influx of immigration, as people sought employment in its booming war factories, military bases, and training facilities, further multiplying the state’s population.

After World War II, California’s economy continued its expansion, propelled by robust aerospace and defense industries, though their size would later decrease following the end of the Cold War. A strategic shift occurred at Stanford University, which began actively encouraging its faculty and graduates to remain in the state and cultivate a high-tech region, an initiative that blossomed into what is now globally recognized as Silicon Valley. As a direct result of these converging forces, California has cemented its position as a world center for the entertainment and music industries, technology, engineering, the aerospace industry, and as the preeminent U.S. center of agricultural production. Just prior to the Dot Com Bust, California proudly stood as the fifth-largest economy in the world, a testament to its dynamic economic prowess.

The mid and late twentieth century were also marked by significant race-related incidents, reflecting persistent social tensions. Unemployment and poverty in inner cities, combined with escalating tensions between police and African Americans, erupted into civil unrest, including the widely reported 1992 Rodney King riots. California also became the hub of the Black Panther Party, an organization known for its advocacy of arming African Americans to defend against racial injustice. Concurrently, Mexican, Filipino, and other migrant farmworkers rallied across the state under the charismatic leadership of Cesar Chavez, fighting for better pay and improved working conditions throughout the 1960s and 70s, a pivotal period in the civil rights movement.

Amidst its periods of growth and social change, the 20th century also witnessed two monumental disasters in California: the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the 1928 St. Francis Dam flood, both of which remain among the deadliest in U.S. history. While significant progress has been made in reducing air pollution, health problems associated with pollution continue to pose a challenge, although the brown haze known as “smog” has been substantially abated following federal and state restrictions on automobile exhaust. An energy crisis in 2001, however, led to widespread rolling blackouts, soaring power rates, and the critical importation of electricity from neighboring states, bringing Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas and Electric Company under heavy criticism for their role.

The early 21st century brought its own set of challenges, particularly the relentless increase in housing prices in urban areas. A modest home that might have cost $25,000 in the 1960s would command half a million dollars or more in urban areas by 2005, forcing more people to commute longer hours from more rural areas to afford homes while earning larger salaries in urban centers. Speculators, anticipating massive short-term profits, bought houses, expecting prices to continue their upward trajectory, with mortgage companies readily compliant in this atmosphere of assumed perpetual growth. This housing bubble spectacularly burst in 2007–08, as prices plummeted, leading to the disappearance of hundreds of billions in property values and a dramatic surge in foreclosures, severely impacting financial institutions and investors across the board.

Amidst these economic fluctuations, Silicon Valley reaffirmed its global technological dominance with the 2007 launch of the iPhone by Apple founder Steve Jobs, solidifying its status as the world’s largest tech hub. In the 21st century, California has grappled with persistent droughts and increasingly frequent and severe wildfires, widely attributed to climate change. The period from 2011 to 2017 saw a relentless drought, recorded as the worst in the state’s history, while the 2018 wildfire season proved to be the deadliest and most destructive on record. The state has also witnessed an increase in atmospheric rivers, leading to intense flooding events, especially during the winter months, highlighting the contrasting and challenging impacts of a changing climate.

California also found itself on the front lines of a global health crisis, with one of the first confirmed COVID-19 cases in the United States reported in the state on January 26, 2020. A state of emergency was declared on March 4, 2020, and remained in effect until Governor Gavin Newsom ended it in February 2023. A mandatory statewide stay-at-home order was issued on March 19, 2020, and was subsequently lifted in January 2021, illustrating the profound and rapid societal adjustments necessitated by the pandemic. Despite these contemporary challenges, cultural and language revitalization efforts among indigenous Californians have made significant progress among tribes as of 2022. Encouragingly, some ancestral lands have been returned to indigenous stewardship, and in a landmark victory for California tribes, the largest dam removal and river restoration project in U.S. history was announced for the Klamath River in 2022, signaling a renewed commitment to environmental justice and indigenous rights.

Geographically, California is a marvel, covering an area of 163,696 sq mi (423,970 km2), making it the third-largest state in the United States after Alaska and Texas. It stands as one of the most geographically diverse states in the union, often conceptually divided into two distinct regions: Southern California, encompassing the ten southernmost counties, and Northern California, comprising the 48 northernmost counties. Its borders are defined by Oregon to the north, Nevada to the east and northeast, Arizona to the southeast, the expansive Pacific Ocean to the west, and an international border with the Mexican state of Baja California to the south, collectively forming part of the Californias region of North America, alongside Baja California Sur.

The state’s heart is dominated by the California Central Valley, a remarkably fertile agricultural area. This valley is bounded by the majestic Sierra Nevada mountains to the east, the coastal mountain ranges to the west, the Cascade Range to the north, and the Tehachapi Mountains to the south. The Central Valley, deeply productive, serves as California’s agricultural heartland, a source of immense bounty that feeds the nation and the world. The valley itself is bisected by the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, with the northern portion, the Sacramento Valley, serving as the watershed of the Sacramento River, and the southern portion, the San Joaquin Valley, being the watershed for the San Joaquin River. Both valleys derive their names from these vital rivers that flow through them.

With strategic dredging, both the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers have been maintained at sufficient depth to allow several inland cities to function as seaports, connecting the agricultural interior to global trade routes. The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is not merely a geographic feature; it is a critical water supply hub for the entire state, underscoring its immense strategic importance. Water is meticulously diverted from this delta through an extensive network of pumps and canals that traverse nearly the entire length of the state, serving the Central Valley, the State Water Projects, and numerous other critical needs. This water provides drinking water for nearly 23 million people, almost two-thirds of California’s population, and irrigates the vast agricultural lands on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley.

Suisun Bay lies at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, its waters draining through the Carquinez Strait, which flows into San Pablo Bay, a northern extension of San Francisco Bay. This intricate system then connects to the vast Pacific Ocean via the iconic Golden Gate strait. Off the Southern coast, the Channel Islands emerge from the Pacific, while the Farallon Islands lie majestically west of San Francisco, adding to the state’s diverse coastal landscape.

The Sierra Nevada, whose name fittingly translates from Spanish as “snowy range,” is home to Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the contiguous 48 states, soaring to 14,505 feet (4,421 m). This range embraces the world-renowned Yosemite Valley, celebrated for its dramatically glacially carved domes, and Sequoia National Park, a sanctuary for the giant sequoia trees, which stand as the largest living organisms on Earth. It also cradles the deep freshwater Lake Tahoe, the largest lake in the state by volume, straddling the California/Nevada border. To the east of the Sierra Nevada lie the Owens Valley and Mono Lake, an essential habitat for migratory birds, while Clear Lake, the largest freshwater lake by area entirely within California, graces the western part of the state. The Sierra Nevada experiences Arctic temperatures in winter and boasts several dozen small glaciers, including the Palisade Glacier, the southernmost glacier in the United States.

Historically, Tulare Lake stood as the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, a remnant of the Pleistocene-era Lake Corcoran. However, by the early 20th century, Tulare Lake had completely dried up, a direct consequence of its tributary rivers being diverted for extensive agricultural irrigation and burgeoning municipal water uses. Approximately 45 percent of California’s total surface area is covered by forests, a remarkable statistic that means California holds more forestland than any other state except Alaska. The state’s diversity of pine species is unparalleled, unmatched by any other state, and within the California White Mountains, some trees stand as the oldest in the world, with individual bristlecone pines exceeding 5,000 years in age, living testaments to time.

In the south of the state lies the Salton Sea, a large inland salt lake, a unique and ecologically complex feature. The south-central desert is known as the Mojave, a vast, arid expanse. To the northeast of the Mojave lies Death Valley, which holds the distinction of containing the lowest and hottest place in North America: the Badwater Basin, at −279 feet (−85 m) below sea level. Remarkably, the horizontal distance from the bottom of Death Valley to the majestic top of Mount Whitney is less than 90 miles (140 km), showcasing the dramatic topographic extremes within the state. Indeed, almost all of southeastern California is characterized by arid, hot desert conditions, with routinely extreme high temperatures during the summer months. The southeastern border of California with Arizona is entirely formed by the mighty Colorado River, from which the southern part of the state derives approximately half of its vital water supply.

A majority of California’s vibrant cities are concentrated in either the San Francisco Bay Area or the Sacramento metropolitan area in Northern California, or within the Greater Los Angeles Area, the Inland Empire, or the San Diego metropolitan area in Southern California. The Los Angeles Area, the Bay Area, and the San Diego metropolitan area stand as prominent examples of the several major metropolitan areas that grace the California coast, serving as economic and cultural powerhouses. Situated as part of the Pacific’s Ring of Fire, California is inherently susceptible to a range of natural phenomena, including tsunamis, floods, droughts, the powerful Santa Ana winds, destructive wildfires, and landslides on its steep terrain. The state also harbors several volcanoes, remnants of its dynamic geological past.

Frequent earthquakes are an undeniable reality of life in California, a direct consequence of numerous active faults crisscrossing the state, the largest and most well-known being the formidable San Andreas Fault. Approximately 37,000 earthquakes are recorded each year, though the vast majority are too small to be felt by residents. Crucially, among all Americans at risk of serious harm from a major earthquake, a significant two-thirds of that population resides within California, underscoring the constant geological vigilance required. Despite these natural challenges, the state continues to thrive, a testament to its inhabitants’ resilience and adaptability.

The climate of California is predominantly Mediterranean across much of the state, characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters. The cool California Current offshore plays a significant role in moderating coastal temperatures, frequently creating the iconic summer fog that envelops the coastline, offering respite from the inland heat. However, the sheer size and diverse topography of California result in climates that vary dramatically from one region to another. These range from moist temperate rainforests in the far north to arid deserts in the interior, and from snowy alpine conditions in the high mountains, reflecting a remarkable meteorological spectrum that contributes to the state’s ecological richness.

Economically, California stands as an undisputed titan, boasting the largest economy of any U.S. state, with an estimated 2024 gross state product of $4.172 trillion as of Q4 2024. This makes it the world’s largest sub-national economy. If California were an independent country, its economy would rank as the fourth-largest globally, as of 2025, positioning it remarkably behind only Germany and ahead of Japan when ranked by nominal GDP, a staggering testament to its immense economic output. The state’s agricultural industry is a national leader, consistently producing the highest agricultural output in the country, significantly fueled by its prodigious production of dairy, almonds, and grapes, which are exported worldwide.

California plays an absolutely pivotal role in the global supply chain, highlighted by the Port of Los Angeles, which is the busiest port in the entire country, handling approximately 40% of all goods imported to the U.S. This critical infrastructure underscores California’s indispensable position in international commerce. Beyond its economic might, California is an undeniable wellspring of popular culture, with notable contributions spanning entertainment, sports, music, and fashion originating from its vibrant landscape. Hollywood in Los Angeles, for instance, is not only the center of the U.S. film industry but also one of the oldest and largest film industries globally, profoundly shaping and influencing global entertainment since the 1920s.

Parallel to Hollywood’s cultural dominance, the San Francisco Bay Area reigns as the undisputed center of the global technology industry, consistently driving innovation and shaping the digital future. This confluence of economic power, cultural influence, and technological advancement positions California as a truly unique and forward-thinking entity on the world stage.

California’s narrative is an extraordinary fusion of ancient landscapes and modern marvels, of deep historical roots and a relentless drive toward the future. It is a land shaped by geological forces, human ambition, and an enduring spirit of innovation. From the mystical origins of its name to its current status as a global economic and cultural powerhouse, California defies simple categorization. It is a testament to the idea that a place can embody both raw natural beauty and the cutting edge of human achievement, constantly adapting, enduring, and inspiring. Its story continues to unfold, a testament to its unique and indelible mark on the world.