Stepping back into the annals of history, few figures loom as large and captivating as Charlemagne, a monarch whose life was a tapestry woven with conquest, reform, and a profound vision for a unified Europe. His reign, spanning from the late 8th to the early 9th centuries, marked a pivotal epoch, transforming the political and social landscape of a continent still reeling from the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Indeed, Charlemagne was not merely a king; he was a force of nature. As King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of what would become known as the Carolingian Empire from 800, he brought together much of Western and Central Europe under a single banner. This monumental achievement made him the first recognized emperor to rule from the west in approximately three centuries, heralding a new era for European civilization.

Born most likely in April 748, Charlemagne was a scion of the formidable Frankish Carolingian dynasty, the eldest son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon. His lineage connected him to the very heart of the Frankish kingdom, a realm that had steadily grown from its foundations in Gaul to encompass vast swathes of present-day France, Switzerland, Germany, and the Low Countries.

To understand Charlemagne’s ascent, one must appreciate the complex political backdrop of Francia. The Merovingian dynasty, which had long ruled, saw its power wane due to divisions and succession crises. Into this vacuum stepped the “mayors of the palace,” powerful aristocrats who effectively wielded control. Charlemagne’s great-grandfather, Pepin of Herstal, and his grandfather, Charles Martel, were key figures in this transition, paving the way for the Carolingians to eventually seize the throne.

Pepin the Short, Charlemagne’s father, boldly deposed the last Merovingian king, Childeric III, in 751 or 752, securing papal sanction for his rule. This vital connection with the papacy would define much of Charlemagne’s own reign. When Pope Stephen II traveled to Francia in 754, seeking aid against the Lombards, he anointed Pepin as king, thereby legitimizing the new dynasty.

It was during this momentous visit that young Charlemagne, alongside his younger brother Carloman, was also anointed, cementing their future as rulers. This early exposure to the nexus of secular and ecclesiastical power undoubtedly shaped his understanding of leadership and divine mandate.

While his precise birth year was debated, with some earlier sources suggesting 742, modern scholars, building on the work of historians like Karl Ferdinand Werner and Matthias Becher, largely accept April 748. This meticulous historical inquiry underscores the dedication to accuracy in understanding such a seminal figure.

The question of Charlemagne’s early education and linguistic prowess offers fascinating insights into his personal development. Einhard, his 9th-century biographer, tells us that his *patrius sermo*, or native tongue, was a Germanic language. However, given the prevalence of “rustic Roman” in Francia, he was likely functionally bilingual in Germanic and Romance dialects from an early age.

Beyond his native speech, Charlemagne also mastered Latin, the formal language of writing and diplomacy, and, according to Einhard, could even understand and perhaps speak some Greek. This linguistic versatility highlights a ruler who was not only a warrior but also intellectually curious, bridging diverse cultural spheres.

His literacy, however, remains a point of scholarly debate. While he usually had texts read aloud and dictated his responses, a common practice for rulers of his time, Einhard noted that he only attempted to learn to write later in life. Paul Dutton, a medievalist, suggests that the evidence for his reading ability is “circumstantial and inferential at best,” concluding that he likely never fully mastered the skill. Regardless, Charlemagne ardently encouraged the study of liberal arts among his children and at his court, fostering a vibrant intellectual environment.

Upon Pepin’s death in 768, Charlemagne and Carloman succeeded their father, embarking on a joint rule. They received separate coronations – Charlemagne at Noyon and Carloman at Soissons – and maintained distinct palaces and spheres of influence. Though considered joint rulers, their relationship quickly soured.

Their immediate concern was the persistent uprising in Aquitaine. They began the campaign together, yet Carloman inexplicably returned to Francia, leaving Charlemagne to complete the campaign alone. This solo success, culminating in the capture of Duke Hunald, brought an end to a decade of war in Aquitaine and starkly highlighted the growing rift between the royal brothers.

The reasons for Carloman’s withdrawal remain uncertain; it could have been a dispute over territorial control or Carloman’s focus on securing his northern Frankish domains. Despite this personal strife, they maintained a joint rule for practical reasons, each working to solidify their positions by gaining the support of the clergy and local elites.

A dramatic turn of events came on December 4, 771, when Carloman died suddenly. Charlemagne seized the moment, swiftly moving to secure his brother’s territory. This decisive action compelled Carloman’s widow, Gerberga, to seek refuge with their children at the court of Desiderius, the Lombard king, setting the stage for future conflicts.

In a clear political maneuver, Charlemagne promptly ended his marriage to Desiderius’s daughter, traditionally known as Desiderata or Gerperga, and married Hildegard, daughter of Count Gerold, a powerful magnate within Carloman’s former kingdom. This move was a direct response to Desiderius sheltering Carloman’s family and a strategic play to secure Gerold’s vital support.

Charlemagne’s first campaigning season as sole king was directed towards the eastern frontier, launching his initial war against the Saxons, who had been raiding Frankish borderlands. He responded decisively, destroying the pagan Irminsul at Eresburg and seizing their gold and silver. This early triumph not only secured his reputation among his brother’s former supporters but also provided the necessary funds for further military action, marking the beginning of over thirty years of nearly continuous warfare against the Saxons.

The stage was now set for the pivotal confrontation with the Lombards. Pope Adrian I, who succeeded Stephen III in 772, appealed to Charlemagne for help in reclaiming papal lands captured by Desiderius. Driven by this appeal and the dynastic threat posed by Carloman’s sons at the Lombard court, Charlemagne gathered his formidable forces.

He first attempted a diplomatic resolution, offering gold to Desiderius for the return of papal territories and his nephews. When this overture was rejected, Charlemagne’s army, commanded by himself and his uncle Bernard, crossed the Alps and laid siege to the Lombard capital of Pavia in late 773.

During this protracted siege, Charlemagne’s second son, also named Charles, was born in 772, and Charlemagne brought the child and his wife, Hildegard, to the camp. Sadly, their daughter Adelhaid, born during this time, died on her journey back to Francia, a poignant personal detail amidst the grand sweep of the military campaign.

Charlemagne left Bernard to maintain the siege at Pavia while he led a force to capture Verona, where Desiderius’s son, Adalgis, had taken Carloman’s sons. Verona fell, and while the fate of his nephews and Carloman’s wife remains unknown – some historians, like Janet Nelson, compare them to the “Princes in the Tower” – Fried suggests they were likely forced into a monastery or possibly murdered, a common solution to dynastic issues of the era.

In April 774, amidst the siege, Charlemagne traveled to Rome to celebrate Easter. Pope Adrian I orchestrated a formal welcome, where the two leaders swore solemn oaths to each other over the relics of St. Peter. Adrian presented a copy of the agreement between Pepin and Stephen III, outlining the papal lands and rights Pepin had pledged to protect. Charlemagne placed a copy of this agreement above St. Peter’s tomb, a powerful symbol of his commitment, before returning to Pavia.

By June 774, disease had struck the Lombard forces, leading to the surrender of Pavia. Charlemagne, in an act described as “extraordinary” and “without parallel” by the authors of *The Carolingian World*, deposed Desiderius and claimed the title of King of the Lombards. Historians suggest that the elective nature of the Lombard monarchy and the elite’s belief that “rightful authority was in the hands of the one powerful enough to seize it” eased this peaceful annexation.

With Lombardy secured, Charlemagne returned to Francia, bringing with him the Lombard royal treasury and the confined Desiderius and his family. The annexation profoundly extended Frankish rule and solidified his standing as the premier power in Western Europe.

However, the consolidation of his vast kingdom was an ongoing endeavor, marked by continuous frontier wars. The Saxons, ever opportunistic, raided Frankish borderlands during Charlemagne’s absence in Italy, prompting immediate reprisals and a renewed series of devastating campaigns.

In 777, Charlemagne held an assembly at Paderborn, where many Saxons submitted to his rule. Yet, the indomitable Saxon magnate Widukind fled to Denmark, preparing for a new rebellion, foreshadowing years of relentless conflict.

The most infamous episode of these Saxon wars occurred in 782, following Widukind’s return and a Frankish defeat. Charlemagne, arriving at Verden, compelled the Saxon magnates to turn over prisoners, whom he regarded as traitors. The annals chillingly record that Charlemagne had 4,500 Saxon prisoners beheaded in the Massacre of Verden, an event Alessandro Barbero calls “perhaps the greatest stain on his reputation.”

In its wake, Charlemagne issued the *Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae*, a harsh set of laws imposing the death penalty for pagan practices, which “constituted a program for the forced conversion of the Saxons” and was “aimed … at suppressing Saxon identity.” This demonstrates his unyielding commitment to Christianization and the integration of conquered territories, even through brutal means.

For the next several years, Charlemagne remained intensely focused on subjugating the Saxons, campaigning through winters and seizing wealth and captives. By 785, he finally suppressed the main Saxon resistance, and Widukind agreed to be baptized with Charlemagne as his godfather, marking a significant, albeit temporary, end to this phase of the Saxon Wars.

Simultaneously, Charlemagne also sought to extend his influence southward into Muslim Spain, al-Andalus. Representatives of dissident factions from Córdoba sought his support, seeing an opportunity to strengthen the kingdom’s southern frontier. However, his campaign in 778 met with a significant setback at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, where his army was ambushed by Basque forces. Despite the defeat, most of his army withdrew intact.

Amidst these expansive campaigns, Charlemagne was also actively building his dynasty. His twin sons, Louis and Lothair, were born while he was in Spain, though Lothair died in infancy. His daughter Rotrude was betrothed to Emperor Constantine VI of the Byzantine Empire, a strategic alliance that would later be broken.

His personal life also saw significant changes. Following the death of Hildegard in 783 from complications of her final pregnancy, Charlemagne’s mother, Bertrada, died shortly thereafter. By the end of the year, he was remarried to Fastrada, the daughter of an East Frankish count, and later, after Fastrada’s death, to Luitgard, an Alamannian noblewoman.

A crucial move in solidifying his dynasty occurred in 781 when he traveled to Rome with his younger children. Pope Adrian I baptized and renamed Carloman to Pepin, the name of his elder half-brother, and then anointed and crowned both the newly renamed Pepin as king of the Lombards and Louis as king of Aquitaine. This was far from a nominal act; the young kings were sent to live in their respective kingdoms under the careful guidance of regents and advisers, marking a novel decentralization of rule.

Despite this careful planning, internal challenges emerged. In 792, his only son without lands, Pepin the Hunchback (whose mother, Himiltrude, was now considered to have had an illegitimate relationship with Charlemagne), conspired with Bavarian nobles to assassinate his father and brothers. The plot was uncovered, and Pepin was sent to a monastery, while many co-conspirators faced execution. This incident underscored the constant vigilance required to maintain power.

Charlemagne’s reign was not solely defined by military expansion; it was also a period of profound reforms in administration, law, education, military organization, and religion. These sweeping changes reshaped Europe for centuries, laying foundational elements for its future development.

A hallmark of his reign was the Carolingian Renaissance, a period of remarkable cultural and intellectual activity. He summoned councils to address theological controversies, such as the adoptionist doctrine, and to formulate responses to the Second Council of Nicaea, as seen at the Council of Regensburg in 792.

The Council of Frankfurt in 794 further cemented his influence over ecclesiastical affairs, confirming positions on adoptionism, recognizing the deposition of Tassilo of Bavaria, setting grain prices, reforming Frankish coinage, and even endorsing prayer in vernacular languages. These detailed reforms reveal a ruler deeply engaged in the societal and spiritual well-being of his realm.

His extended wars in Saxony ultimately led him to establish his court in Aachen, strategically located with easy access to the frontier. Here, he constructed a magnificent palace, including a chapel that forms part of the impressive Aachen Cathedral today, a testament to his vision and enduring legacy. It was around this time that Einhard, his famous biographer, joined the court.

Beyond the Saxon frontiers, Pepin of Italy, his son, engaged in further successful wars against the Avars in the south, leading to the collapse of their kingdom and the eastward expansion of Frankish rule, further cementing the Carolingian dynasty’s dominance.

Charlemagne also skillfully expanded his influence through diplomatic channels. He forged alliances with Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, notably with King Offa of Mercia, establishing formal peace in 796 that protected trade and secured rights for English pilgrims. He even hosted and protected several deposed English rulers, treating the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms “like satellite states,” and cultivating direct relations with English bishops, showcasing his broad diplomatic reach.

The culmination of Charlemagne’s extraordinary career arrived on Christmas Day 800 in Rome, an event that would forever alter the course of European history. Pope Leo III, facing severe political opposition and a physical attack in April 799 that left him seeking Charlemagne’s aid, had fled north to meet him at Paderborn.

After hearing evidence from the pope and his accusers, Charlemagne sent Leo back to Rome with royal legates instructed to reinstate the pope and conduct further investigation. In November of the following year, Charlemagne himself made a ceremonial entry into Rome, meeting Leo near Mentana.

Presiding over an assembly, Charlemagne believed that no one could sit in judgment of the pope. Thus, on December 23, Leo swore an oath declaring his innocence of all charges. Two days later, during a mass in St. Peter’s Basilica, Leo proclaimed Charlemagne “emperor of the Romans” (*Imperator Romanorum*) and crowned him, simultaneously anointing his son, Charles the Younger, as king.

This momentous coronation marked Charlemagne as the first reigning emperor in the West since Romulus Augustulus’s deposition in 476, a staggering three centuries earlier. The event’s intentions and Charlemagne’s awareness of its planning have been topics of intense historical debate.

Einhard famously wrote that Charlemagne “would not have entered the church if he knew about the pope’s plan,” a statement that modern historians have both accepted as truthful and dismissed as a literary device to demonstrate his humility. However, scholars like Roger Collins and Johannes Fried suggest that the actions surrounding the coronation indicate it was planned by Charlemagne as early as his meeting with Leo in 799, or “at the latest” by 798.

Charlemagne’s courtier, Alcuin, had already begun referring to his realm as an *Imperium Christianum* (“Christian Empire”), suggesting a vision where a common Christian faith would unite a new empire, much as Roman citizenship had united the old. Henri Pirenne supported this, viewing Charlemagne as “the Emperor of the ecclesia as the Pope conceived it, of the Roman Church, regarded as the universal Church.”

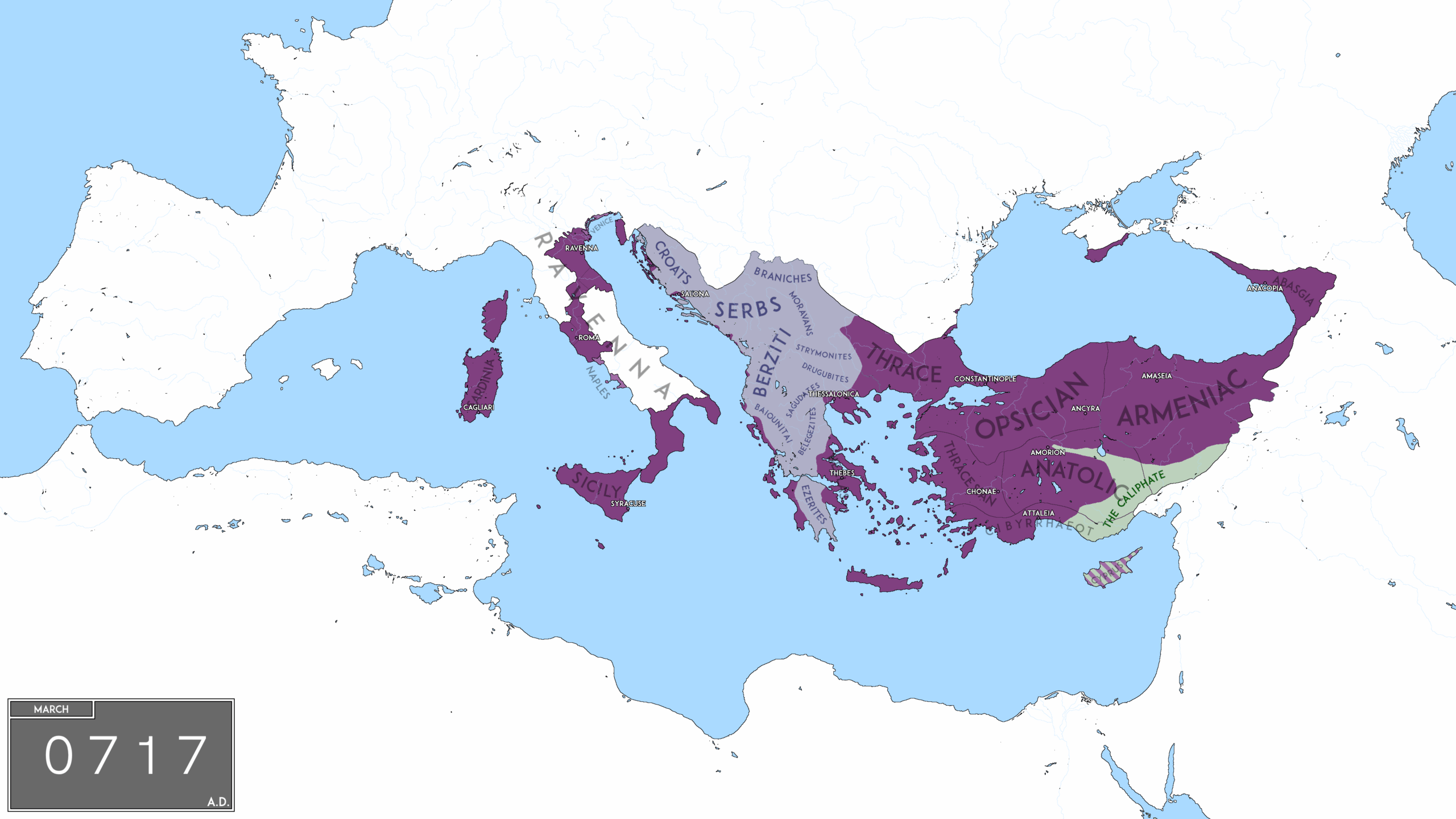

The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, with its own emperor in Constantinople, remained a significant contemporary power. Empress Irene had seized the throne from her son in 797, raising questions about a female ruler. The *Annals of Lorsch*, an early source, presented Irene’s rule as a vacancy in the imperial title, thereby justifying Leo’s coronation of Charlemagne. However, Pirenne disagreed, asserting that the coronation “was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople.”

Pope Leo’s primary motivations likely stemmed from a desire to enhance his standing after his political difficulties, positioning himself as a power broker and securing Charlemagne as a powerful ally and protector, especially given the Byzantine Empire’s limited ability to influence events in Italy. The *Royal Frankish Annals* even describe Leo prostrating himself before Charlemagne after the crowning, an act of submission common in Roman coronation rituals, presenting Leo as an agent of the Roman people acclaiming Charlemagne, rather than his superior.

Historians also ponder the deeper implications of the imperial title. Henry Mayr-Harting posited that it was an effort to incorporate the Saxons into the Frankish realm, as they lacked a tradition of kingship. However, other scholars, like Costambeys et al., counter that “since Saxony had not been in the Roman empire, it is hard to see on what basis an emperor would have been any more welcomed.” They argue that the decision aimed at furthering Charlemagne’s influence in Italy, appealing to the traditional authority recognized by Italian elites.

Collins further suggests that becoming emperor gave Charlemagne “the right to try to impose his rule over the whole of [Italy],” recognizing the “element of political and military risk” given Byzantine opposition. Yet, Charlemagne took pains to ensure his new title had a distinctly Frankish context, adopting the formula “Charles, most serene augustus, crowned by God, great peaceful emperor governing the Roman empire, and who is by the mercy of God king of the Franks and the Lombards,” consciously avoiding the specific claim of being a “Roman emperor.”

This coronation ignited a centuries-long ideological conflict known as the “problem of two emperors,” a profound rejection or usurpation of the Byzantine emperors’ claim to be the universal, preeminent rulers of Christendom. Nevertheless, the title undeniably bestowed enhanced prestige and ideological authority upon Charlemagne, allowing him to embark upon a grand new phase of his transformative reign.

From his early days as a co-ruler to his ultimate elevation as emperor, Charlemagne carved an indelible mark on Western civilization. He was a strategic military leader, a tireless reformer, and a visionary who fostered a renewed sense of learning and cultural identity. His meticulous efforts in administration, law, and education laid the groundwork for future European states, shaping their very governance and intellectual spirit. He unified disparate lands, propagated Christianity, and established a political framework that would echo through the Middle Ages.

His legacy, though complex and at times marked by harsh measures necessary for the era, shines brightly as a beacon of medieval ambition and achievement. Charlemagne, the man who bridged the ancient Roman world with the emerging European identity, truly deserves his epithet, “the Great,” for his profound and lasting impact on the continent’s destiny. He remains an inspirational testament to what determined leadership, coupled with a far-reaching vision, can achieve in the grand theater of human history.