In the intricate and often tense geopolitical theater of the Indo-Pacific, the F-35 fighter jet stands as a potent symbol of American military might and strategic resolve. Regarded by many as the pinnacle of combat aircraft currently in active service worldwide, this fifth-generation fighter is increasingly deployed to deter the formidable and rapidly modernizing Chinese military. Its presence signals a clear commitment from the United States and its allies to maintain regional stability and project power in a crucial global hotspot.

Yet, beneath the surface of this formidable projection of power, a complex web of operational challenges and strategic vulnerabilities is emerging. The F-35, for all its advanced capabilities, is grappling with significant internal issues, particularly concerning its engine performance. Concurrently, China, acutely aware of the growing presence of these American-made stealth aircraft, is not only developing its own advanced fifth-generation fighters but is also leveraging an often-overlooked, yet profoundly strategic, asset: its near monopoly on rare earth elements.

This article delves into these multifaceted dynamics, offering an in-depth examination of the F-35’s critical role in the Indo-Pacific, the inherent difficulties plaguing its operational readiness, and the chilling reality of China’s potential ‘kill switch’ over critical global supply chains. We will explore the strategic implications of these factors, painting a comprehensive picture of the delicate balance of power in one of the world’s most vital regions.

1. **The F-35’s Pivotal Role in the Indo-Pacific Strategy** The F-35 fighter aircraft is widely regarded as one of the most valuable military assets within the U.S. military, consistently mentioned as crucial equipment for carrying out air operations against potential opponents such as China, especially within the strategically vital Indo-Pacific area. Its deployment underscores a fundamental component of the American defense posture in a region characterized by escalating geopolitical competition and territorial disputes.

A few days ago, the U.S. Air Force underscored this strategic emphasis by announcing the deployment of F-35 Lightning II fighters to Okinawa. This move is part of an ongoing process to replace its permanently stationed F-15 Eagles at Kadena Air Base in Japan, signaling a shift towards more advanced capabilities. The Kadena base itself is strategically positioned approximately 450 miles from Taiwan, promoting itself as the crucial and central point of the Pacific region.

This commitment extends beyond mere replacement; it is a clear effort by the Air Force to upgrade its regional presence with newer, more advanced aircraft boasting superior capabilities. While other fifth-generation aircraft, namely the F-22 and the F-16, are already stationed at Kadena Air Base, the additional deployment of F-35s is specifically intended to further bolster the U.S. Air Force’s regional footprint and enhance its deterrent capabilities.

2. **Advanced Capabilities: The F-35’s Technological Edge** The relevance of the F-35 fighter aircraft in the Indo-Pacific area is inextricably linked to its cutting-edge technology, impressive capabilities, and remarkable adaptability across various military operations. It represents a significant leap forward in aviation design, incorporating features that make it a formidable force multiplier in modern warfare scenarios.

At the heart of its strategic value are its advanced stealth features, which are meticulously designed to evade detection by radar. This inherent ability to operate with a reduced signature makes the F-35 an exceptionally valuable asset for conducting covert missions, allowing for deeper penetration into contested airspace without immediate detection. Such capabilities are paramount in environments where maintaining air superiority and surprise are critical.

Beyond its stealth, the F-35 is comprehensively equipped with sophisticated sensors and communication systems. These integrated systems allow it to gather and transmit vital intelligence data in real time, a feature that is essential for making smart, timely decisions during complex military operations. This comprehensive situational awareness ensures that the F-35 can deliver necessary air support and execute precise attacks on crucial targets, making it a critical tool against adversaries like China and North Korea.

Military equipment: Shenyang J-35

Name: Shenyang J-35

TopSpeed: mach 2

Caption: J-35A at 2024 Zhuhai Air Show

Type: Multirole fighter,Stealth aircraft

NationalOrigin: China

Manufacturer: Shenyang Aircraft Corporation

DesignGroup: 601 Institute

FirstFlight: 31 October 2012 (FC-31),29 October 2021 (J-35),26 September 2023 (J-35A)

Status: Development

Produced: 2012–2016 (FC-31) ,2021–present (J-35)

NumberBuilt: 8+

DevelopedFrom: #Shenyang FC-31

Categories: 2020s Chinese fighter aircraft, Aircraft first flown in 2021, Aircraft specs templates using afterburner without dry parameter, Aircraft with retractable tricycle landing gear, All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

Summary: The Shenyang J-35 (Chinese: 歼-35; pinyin: jiān-sānwǔ) is a series of Chinese single-seater, twin-engine, all-weather, stealth multirole combat aircraft manufactured by Shenyang Aircraft Corporation (SAC), designed for air superiority and surface strike missions. The aircraft has two variants, a land-based variant designed for the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF), and a carrier-based variant optimized for catapult-assisted takeoff but arrested recovery (CATOBAR) for the People’s Liberation Army Naval Air Force (PLANAF).

The aircraft was developed from the FC-31 Gyrfalcon (Chinese: 鹘鹰; pinyin: Gǔ yīng), a stealth aircraft prototype that served as a demonstrator aiming to secure potential export customers after SAC lost the J-XX bid to the Chengdu Aircraft Industry Group.

The People’s Liberation Army, particularly the PLA Navy, later took an interest in the FC-31 project, leading to the prototype being further developed with a catapult launch bar and folding wings, and the revised variant took flight on 29 October 2021. A land-based variant emerged in 2023 and was officially debuted ahead of the 2024 China International Aviation & Aerospace Exhibition, receiving the designation J-35A. The aircraft was unofficially called J-31 by some media and analysts until the official name announced as the J-35.

Get more information about: Shenyang J-35

3. **A Region in Flux: The Increasing Presence of Fifth-Generation Aircraft** The deployment of F-35s to Kadena Air Base is not an isolated event but rather part of a broader, accelerating trend across Asia. This trend involves a significant and increasing presence of fifth-generation combat aircraft, signaling a regional arms race towards advanced aerial capabilities. The strategic landscape is rapidly evolving with more nations acquiring or planning to acquire these sophisticated platforms.

Crucially, key U.S. allies in the region, South Korea and Japan, have already established and are operating their own fleets of F-35 fighter jets, integrating them into their national defense strategies. This widespread adoption among allies enhances interoperability and creates a more robust collective deterrent in the Indo-Pacific. Furthermore, Singapore also operates F-35 fighter jets and, earlier this year, declared its intention to place an order for eight more F-35B Lightning II combat jets, underscoring the perceived value of these aircraft.

Even Thailand, a nation with strong defense connections to Beijing, has made a decision to acquire F-35 fighters and is currently awaiting approval from the United States. This indicates a broader recognition of the F-35’s strategic importance, even among countries that maintain relationships with China. Looking ahead, it is anticipated that over 300 F-35 fighters will be stationed across the Indo-Pacific region by 2035, with a growing list of users including Australia, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and the United States, cementing its dominant presence.

Military equipment: Glock

Name: Glock

Caption: Norwegian Armed Forces

Origin: Austria

Type: Semi-automatic pistol,Machine pistol

IsRanged: true

Service: 1982–present

UsedBy: #Users

Wars: Russian invasion of Ukraine

Designer: Gaston Glock

DesignDate: 1979–1982

Manufacturer: Glock GmbH

ProductionDate: 1982–present

Number: 20,000,000 as of 2020

Variants: #Variants

Cartridge: 9×19mm Parabellum,10mm Auto,.22 LR,.357 SIG,.380 ACP,.40 S&W,.45 ACP,.45 GAP

Action: Recoil operation#Short recoil operation

Rate: 1,100–1,400 rounds/min (Glock 18)

Velocity: 375 m

Abbr: on (Glock 17, 17C, 18, 18C)

Range: 50 m

Feed: drum magazine

Categories: .22 LR pistols, .357 SIG semi-automatic pistols, .380 ACP semi-automatic pistols, .40 S&W semi-automatic pistols, .45 ACP semi-automatic pistols

Summary: Glock (German: [ˈglɔk]; stylized as GLOCK) is a line of polymer‑framed, striker‑fired semi‑automatic pistols designed and manufactured by the Austrian company Glock GmbH, founded by Gaston Glock in 1963 and headquartered in Deutsch‑Wagram, Austria. The first model, the 9×19 mm Glock 17, entered service with the Austrian military and police in 1982 after performing exceptionally in reliability and safety testing. Glock pistols have since gained international prominence, being adopted by law enforcement and military agencies in over 48 countries and widely used by civilians for self‑defense, sport shooting, and concealed carry. As of 2020, over 20 million units have been produced, making it Glock’s most profitable product line. Glock’s distinctive design polymer frame, simplified controls with its Safe Action system, and minimal components set a new standard in modern handgun engineering and spurred similar designs across the industry.

Get more information about: Glock

4. **The Unsettling Reality of F-35 Engine Readiness** Despite its impressive capabilities and strategic importance, the F-35 is currently facing significant operational difficulties, primarily due to persistent problems linked to its current engine. These issues throw a considerable spanner in the smooth operation of these advanced fighter jets, raising concerns about their true readiness rates and overall fleet availability for critical missions.

On March 29, a top U.S. official revealed that the Pratt & Whitney F135 engines, which power the F-35 fighter aircraft, have been “under spec since the beginning.” This inherent design challenge necessitates consistently operating the engines at higher-than-anticipated temperatures. Such sustained elevated temperatures contribute directly to increased maintenance and logistics activities, subsequently degrading the F-35’s overall readiness rates.

The impact of these engine issues on fleet readiness is stark. According to the F-35 Program Executive Officer, the Pentagon’s F-35 fighter jet fleet has only around half of its deemed mission-capable aircraft, a figure significantly less than the 65% target. During his first appearance before Congress as the F-35 Program Executive Officer, Air Force Lt. Gen. Mike Schmidt expressed his profound dissatisfaction, noting that as of February 2023, the average monthly rate of operational jets in the fleet of over 540 F-35s was a mere 53.1%. This figure, which indicates aircraft capable of carrying out some essential missions, falls well short of desired thresholds, and the proportion of aircraft capable of carrying out their full missions was reported to be less than 30%.

Military equipment: False or misleading statements by Donald Trump

Categories: All Wikipedia articles in need of updating, All Wikipedia articles written in American English, All articles lacking reliable references, All articles that may be too long, All articles with dead external links

Summary: Donald Trump has made tens of thousands of false or misleading claims, including as President of the United States. Fact-checkers at The Washington Post documented 30,573 false or misleading claims during his first presidential term, an average of 21 per day. The Toronto Star tallied 5,276 false claims from January 2017 to June 2019, an average of six per day. Commentators and fact-checkers have described Trump’s lying as unprecedented in American politics, and the consistency of falsehoods as a distinctive part of his business and political identities. Scholarly analysis of Trump’s X posts found significant evidence of an intent to deceive.

Many news organizations initially resisted describing Trump’s falsehoods as lies, but began to do so by June 2019. The Washington Post said his frequent repetition of claims he knew to be false amounted to a campaign based on disinformation. Steve Bannon, Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign CEO and chief strategist during the first seven months of Trump’s first presidency, said that the press, rather than Democrats, was Trump’s primary adversary and “the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.” In February 2025, a public relations CEO stated that the “flood the zone” tactic (also known as the firehose of falsehood) was designed to make sure no single action or event stands out above the rest by having them occur at a rapid pace, thus preventing the public from keeping up and preventing controversy or outrage over a specific action or event.

As part of their attempts to overturn the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Trump and his allies repeatedly falsely claimed there had been massive election fraud and that Trump had won the election. Their effort was characterized by some as an implementation of Hitler’s “big lie” propaganda technique.

In June 2023, a criminal grand jury indicted Trump on one count of making “false statements and representations”, specifically by hiding subpoenaed classified documents from his own attorney who was trying to find and return them to the government. In August 2023, 21 of Trump’s falsehoods about the 2020 election were listed in his Washington, D.C. criminal indictment, and 27 were listed in his Georgia criminal indictment.

It has been suggested that Trump’s false statements amount to bullshit rather than lies.

Get more information about: False or misleading statements by Donald Trump

5. **Addressing Operational Woes: The Push for Engine Enhancements** Recognizing the critical nature of the F135 engine’s shortcomings, top U.S. military leaders have explicitly underlined these issues when justifying a decision to undertake an Engine Core Upgrade (ECU) initiative. This proposed enhancement is viewed as critical for all F-35 Joint Strike Fighter types, aiming to mitigate the existing operational difficulties. Interestingly, in the Pentagon’s Fiscal Year 2024 budget proposal, the U.S. military chose to reject the idea of developing an entirely new engine for their F-35s, based on the Advanced Engine Transition Program (AETP), citing high anticipated costs and technical challenges associated with such a venture.

The military found an upgrade important because the “Power and Thermal Management System,” a component built by a Lockheed Martin subcontractor, “is underperforming,” directly leading to reduced engine life. In pre-written statements, Lt. Gen. Mike Schmidt clearly expressed that the current readiness rate is unacceptable and declared that his primary objective is to maximize readiness. He outlined an ambitious goal to raise readiness rates by a minimum of 10% within the next 12 months, highlighting the urgency of these improvements.

In the past, various factors have been identified as contributing to the persistent decrease in readiness rates. These include a consistent lack of spare parts and frequent breakages of parts and engine components, which have occurred beyond initial expectations. Additionally, prolonged depot repair times and a need for faster-than-anticipated repairs or replacements of Pratt & Whitney engine power modules have further compounded the challenges. Problems with the F135 engine have become increasingly noticeable in recent years, with a significant maintenance backlog attributed, two years ago, to issues like the engines’ turbine blades’ heat-protective coatings wearing out earlier than anticipated.

Military equipment: Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor

Name: F-22 Raptor

Caption: Kadena Air Base

Alt: F-22 Raptor flies over Kadena Air Base, Japan on a flight training mission in 2009

Type: Air superiority fighter

NationalOrigin: United States

Manufacturer: Lockheed Martin Aeronautics,Boeing Defense, Space & Security

FirstFlight: Start date and age

Introduction: 15 December 2005

Status: In service

PrimaryUser: United States Air Force

Produced: 1996–2011

NumberBuilt: 195 (8 test and 187 operational aircraft)

DevelopedFrom: Lockheed YF-22

DevelopedInto: Lockheed Martin X-44 MANTA,Lockheed Martin FB-22

Categories: 1990s United States fighter aircraft, Aircraft first flown in 1997, Aircraft specs templates using more power parameter, Aircraft with retractable tricycle landing gear, All Wikipedia articles written in American English

Summary: The Lockheed Martin/Boeing F-22 Raptor is an American twin-engine, jet-powered, all-weather, supersonic stealth fighter aircraft. As a product of the United States Air Force’s Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) program, the aircraft was designed as an air superiority fighter, but also incorporates ground attack, electronic warfare, and signals intelligence capabilities. The prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, built most of the F-22 airframe and weapons systems and conducted final assembly, while program partner Boeing provided the wings, aft fuselage, avionics integration, and training systems.

First flown in 1997, the F-22 descended from the Lockheed YF-22 and was variously designated F-22 and F/A-22 before it formally entered service in December 2005 as the F-22A. It replaced the F-15 Eagle in most active duty U.S. Air Force (USAF) squadrons. Although the service had originally planned to buy a total of 750 ATFs to replace its entire F-15 fleet, it later scaled down to 381, and the program was ultimately cut to 195 aircraft – 187 of them operational models – in 2009 due to political opposition from high costs, a perceived lack of air-to-air threats at the time of production, and the development of the more affordable and versatile F-35 Lightning II. The last aircraft was delivered in 2012.

The F-22 is a critical component of the USAF’s tactical airpower as its high-end air superiority fighter. While it had a protracted development and initial operational difficulties, the aircraft became the service’s leading counter-air platform against peer adversaries. Although designed for air superiority operations, the F-22 has also performed strike and electronic surveillance, including missions in the Middle East against the Islamic State and Assad-aligned forces. The F-22 is expected to remain a cornerstone of the USAF’s fighter fleet until its succession by the Boeing F-47.

Get more information about: Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor

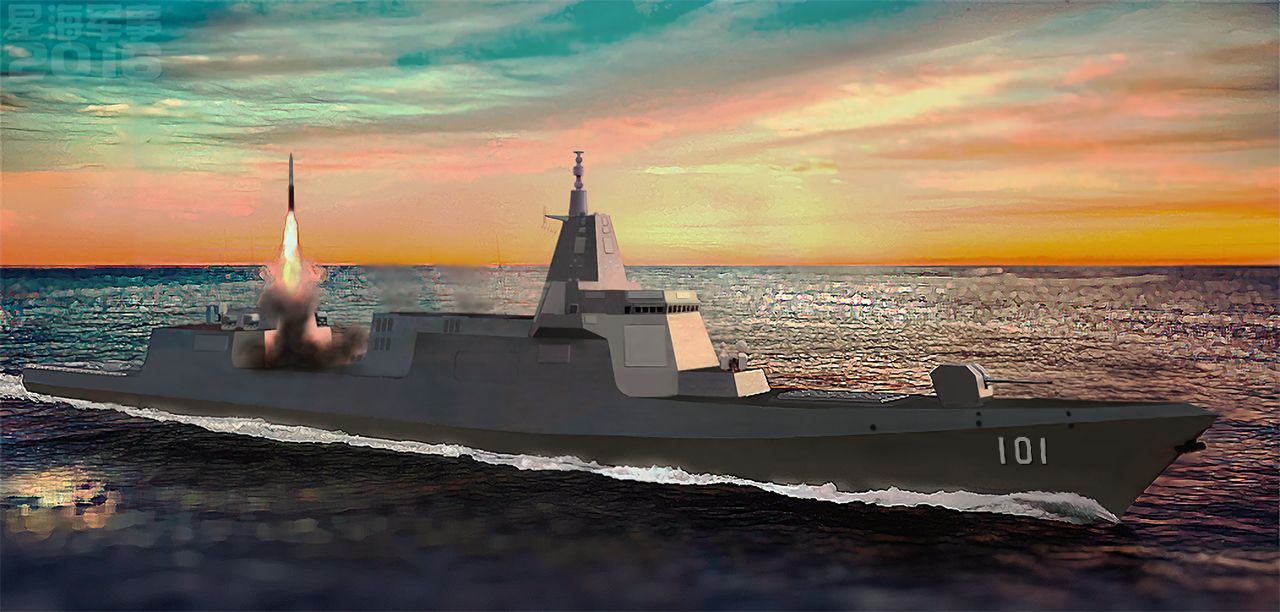

6. **China’s J-20: A Direct Challenge to F-35 Dominance** China is demonstrably well aware of the growing presence of American-made stealth aircraft, particularly the F-22 and F-35, in the Indo-Pacific region. Beijing views these deployments as a direct challenge to its strategic interests and regional ambitions, prompting a concerted effort to develop and field its own advanced combat platforms as a countermeasure. This dynamic sets the stage for a potential high-stakes aerial confrontation.

To effectively counterbalance the increasing deployment of these advanced American stealth fighters, Beijing has significantly stepped up production of its own fifth-generation J-20s in recent years. The J-20, a Chengdu-built stealth fighter, represents China’s answer to the F-35 and F-22, designed to project air power and challenge the dominance of Western advanced aircraft in the region. This accelerated production rate signifies a clear commitment to achieving technological parity or even superiority in key areas of air combat.

Given these parallel developments, military analysts widely anticipate that a confrontation between American-manufactured fifth-generation fighters and the J-20 is highly likely to occur in the event of a future conflict. Such an encounter would serve as a critical test of each nation’s respective air superiority technologies and operational doctrines, potentially shaping the outcome of any significant engagement in the Indo-Pacific.

7. **The ‘Kill Switch’: China’s Rare Earth Dominance and US Vulnerability** The F-35 Lightning II stealth fighter is considered by its makers to be the pinnacle of combat aircraft currently in active service worldwide, designed to play a pivotal role for the United States in any future conflict. Intriguingly, it was once rumored to have a “kill switch,” a claim vehemently denied by the U.S. military and its manufacturer, Lockheed Martin. However, a new revelation indicates that while a ‘kill switch’ does indeed exist for the F-35, its control does not lie with the United States. Instead, its arch-rival, China, possesses the means to activate this ‘kill switch,’ potentially rendering the entire F-35 program, and several other critical U.S. military platforms, ineffective.

China enjoys an unparalleled domination in the global supply of rare earths and critical elements, which are indispensable components in virtually all advanced weapon platforms. The country is not only the world’s largest producer and consumer of these essential materials but also their biggest exporter. The United States, in particular, is heavily dependent on these rare earths and critical elements for maintaining its defense technological edge, with over 80 percent of its weapons systems utilizing them. This deep reliance creates a profound strategic vulnerability.

Should China decide to exert its leverage by refusing to supply rare earths and critical elements to the U.S., the latter’s defense industry could face a grinding halt. The Pentagon would effectively be “blinded” in the event of such a disruption in the supply of these critical components. China controls more than 90 percent of the world’s processing and refining units for rare earths and is responsible for producing an astonishing 98.8 percent of refined gallium in the world, a substance that plays a crucial role in GPS systems and radars. This near-monopoly presents a clear and present danger to U.S. forces, leaving them with no discernible counter to this strategic ‘kill switch’.”

Military equipment: China–United States relations

Envoytitle1: List of ambassadors of China to the United States

Envoy1: Xie Feng (diplomat)

Envoytitle2: List of ambassadors of the United States to China

Envoy2: David Perdue

Mission1: Embassy of China, Washington, D.C.

Mission2: Embassy of the United States, Beijing

Map: China USA Locator.svg

Categories: All Wikipedia articles in need of updating, All Wikipedia articles written in American English, All articles lacking reliable references, All articles that may be too long, All articles with dead external links

Summary: The relationship between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States of America (USA) is the most important bilateral relationship in the world. It has been complex and at times tense since the establishment of the PRC and the retreat of the government of the Republic of China to Taiwan in 1949. Since the normalization of relations in the 1970s, the US–China relationship has been marked by persistent disputes including China’s economic policies, the political status of Taiwan and territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Despite these tensions, the two nations have significant economic ties and are deeply interconnected, while also engaging in strategic competition on the global stage. As of 2025, China and the United States are the world’s second-largest and largest economies by nominal GDP, as well as the largest and second-largest economies by GDP (PPP) respectively. Collectively, they account for 44.2% of the global nominal GDP, and 34.7% of global PPP-adjusted GDP. One of the earliest major interactions between the United States and China was the 1845 Treaty of Wangxia, which laid the foundation for trade between the two countries. While American businesses anticipated a vast market in China, trade grew gradually. In 1900, Washington joined the Empire of Japan and other powers of Europe in sending troops to suppress the xenophobic Boxer Rebellion, later promoting the Open Door Policy to advocate for equal trade opportunities and discourage territorial divisions in China. Despite hopes that American financial influence would expand, efforts during the Taft presidency to secure US investment in Chinese railways were unsuccessful. President Franklin D. Roosevelt supported China during the Second Sino-Japanese War, aligning with the Republic of China (ROC) government, which had formed a temporary alliance with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to fight the Japanese. Following Japan’s defeat, the Chinese Civil War resumed, and US diplomatic efforts to mediate between the Nationalists and Communists ultimately failed. The Communist forces prevailed, leading to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, while the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan. Relations between the US and the new Chinese government quickly soured, culminating in direct conflict during the Korean War. The US-led United Nations intervention was met with Chinese military involvement, as Beijing sent millions of Chinese fighters to prevent a US-aligned presence on its border. For decades, the United States did not formally recognize the PRC, instead maintaining diplomatic relations with the ROC based in Taiwan, and as such blocked the PRC’s entry into the United Nations. However, shifting geopolitical dynamics, including the Sino-Soviet split, the winding down of the Vietnam War, as well as of the Cultural Revolution, paved the way for US President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, ultimately marking a sea change in US–China relations. On 1 January 1979, the US formally established diplomatic relations with the PRC and recognized it as the sole legitimate government of China, while maintaining unofficial ties with Taiwan within the framework of the Taiwan Relations Act, an issue that remains a major point of contention between the two countries to the present day. Every US president since Nixon has toured China during their term in office, with the exception of Jimmy Carter and Joe Biden. The Obama administration signed a record number of bilateral agreements with China, particularly regarding climate change, though its broader strategy of rebalancing towards Asia created diplomatic friction. The advent of Xi Jinping’s general secretaryship would prefigure a sharp downturn in these relations, which was then further entrenched upon the election of President Donald Trump, who had promised an assertive stance towards China as a part of his campaign, which began to be implemented upon his taking office. Issues included China’s militarization of the South China Sea, alleged manipulation of the Chinese currency, and Chinese espionage in the United States. The Trump administration would label China a “strategic competitor” in 2017. In January 2018, Trump launched a trade war with China, while also restricting American companies from selling equipment to various Chinese companies linked to human rights abuses in Xinjiang, among which included Chinese technology conglomerates Huawei and ZTE. The US revoked preferential treatment towards Hong Kong after the Beijing’s enactment of a broad-reaching national security law in the city, increased visa restrictions on Chinese students and researchers, and strengthened relations with Taiwan. In response, China adopted “wolf warrior diplomacy”, countering US criticisms of human rights abuses. By early 2018, various geopolitical observers had begun to speak of a new Cold War between the two powers. On the last day of the Trump administration in January 2021, the US officially classified the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang as a genocide. Following the election of Joe Biden in the 2020 United States presidential election, tensions between the two countries remained high. Biden identified strategic competition with China as a top priority in his foreign policy. His administration imposed large-scale restrictions on the sale of semiconductor technology to China, boosted regional alliances against China, and expanded support for Taiwan. However, the Biden administration also emphasized that the US sought “competition, not conflict”, with Biden stating in late 2022 that “there needs to not be a new Cold War. Despite efforts at diplomatic engagement, US-China trade and political relations have reached their lowest point in years, largely due to disagreements over technology and China’s military growth and human rights record. In his second term, President Donald Trump sharply escalated the trade war with China, raising baseline tariffs on Chinese imports to an effective 145%, prior to negotiating with China on 12 May 2025 a reduction in the tariff rate to 30% for 90 days while further negotiations take place.

Get more information about: China–United States relations

8. **China’s Advanced Anti-Stealth Capabilities**Despite the F-35’s formidable stealth features, designed to evade detection by radar, China claims to have developed technology capable of tracking these advanced aircraft. This counter-stealth capability reportedly utilizes its BeiDou satellite system, leveraging characteristics that stealth models aim to minimize, such as their tell-tale exhaust plumes. The South China Morning Post, in a February 2025 report, highlighted the immense potential of such technology.

Scientists from the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics reportedly demonstrated the ability to ‘see’ an F-35 from over 1,110 miles away. This was achieved using an “unmanned airship hovering at 20km … deploying mercury-cadmium-telluride detectors and 300mm aperture telescopes,” primarily by detecting the aircraft’s considerable heat signature. While the F-35’s radar-absorbing coating and exterior cool to low temperatures, its engine exhaust plume, reaching nearly 1,000 Kelvin, emits mid-wave infrared radiation three orders of magnitude stronger than its airframe, presenting a significant vulnerability for detection.

Furthermore, this new Chinese technology may even be able to exploit the F-35’s ability to distort and muddle incoming signals. By interpreting the confused radar signals left behind, it could potentially determine the position of the disturbance and reconstruct a picture of the hidden aircraft. The Eurasian Times reported that “with the use of BeiDou signals, the radar can detect refraction patterns caused by stealth aircraft,” creating unique echoes that allow scientists to estimate the aircraft’s type and location. This turns a primary asset of stealth aircraft into a potential liability, raising questions about the future of stealth technology, though significant refinement is needed for regular operational use given that “normal atmospheric phenomena or normal planes can produce the same effect.

9. **The F-35’s Declining International Appeal**Beyond the direct technological challenges posed by adversaries, the F-35 program is facing growing scrutiny and diminishing interest from traditional U.S. allies. What was once the “hottest ticket in the international arms market,” lauded for its stealth, supersonic capabilities, and versatility, is now encountering significant qualms from nations that had previously committed to its acquisition or were considering it. This trend signals a broader reassessment of the geopolitical and economic implications of purchasing American-made defense systems.

Switzerland, for instance, chose the F-35 over France’s Dassault Rafale, a decision now facing considerable backlash. The Trump administration’s subsequent increase in the F-35’s cost and the imposition of harsh trade tariffs on Swiss exports, including a 39 percent tariff, have fueled political opposition. As Politico reported, an order for 36 F-35 jets “may become a casualty of Donald Trump’s trade war against Switzerland,” with efforts underway in the Swiss Parliament to cancel the deal.

This pattern extends to other European nations. Spain has reportedly shelved plans to buy F-35s, instead choosing between European-made Eurofighter and the Future Combat Air System (FCAS). Similarly, a leading Danish defense official expressed regret over his country’s F-35 purchases, stating, “buying American weapons is a security risk that we cannot run,” and emphasizing the need to “avoid American weapons if at all possible.” Portugal and Canada have also reportedly lost interest, indicating a broader trend of allies reassessing the long-term strategic and economic wisdom of exclusive reliance on the F-35.

Military equipment: Amnesty International

Logo: Amnesty International logo.svg

LogoSize: 250px

Type: Nonprofit organization,International non-governmental organization

Headquarters: London,[object Object]

Services: Protecting human rights

NumEmployees: 3,600

LeaderTitle: Secretary-General

LeaderName: Agnès Callamard

Name: Amnesty International

Founded: [object Object]

Founders: Peter Benenson,Eric Baker (activist),Seán MacBride

Location: Global

Fields: Media attention, direct-appeal campaigns, research, lobbying

NumMembers: More than ten million members and supporters

Homepage: official url

Categories: 1961 establishments in England, Abortion-rights organisations in the United Kingdom, All accuracy disputes, All articles lacking reliable references, All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

Summary: Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members and supporters around the world. The stated mission of the organization is to campaign for “a world in which every person enjoys all of the human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. The organization has played a notable role on human rights issues due to its frequent citation in media and by world leaders.

AI was founded in London in 1961 by the lawyer Peter Benenson. In what he called “The Forgotten Prisoners” and “An Appeal for Amnesty”, which appeared on the front page of the British newspaper The Observer, Benenson wrote about two students who toasted to freedom in Portugal and four other people who had been jailed in other nations because of their beliefs. AI’s original focus was prisoners of conscience, with its remit widening in the 1970s, under the leadership of Seán MacBride and Martin Ennals, to include miscarriages of justice and torture. In 1977, it was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In the 1980s, its secretary general was Thomas Hammarberg, succeeded in the 1990s by Pierre Sané. In the 2000s, it was led by Irene Khan.

Amnesty draws attention to human rights abuses and campaigns for compliance with international laws and standards. It works to mobilize public opinion to generate pressure on governments where abuse takes place.

Get more information about: Amnesty International

10. **Internal Debates on PLA’s Combat Readiness**The rapid modernization of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has led many U.S. defense experts to view it as a formidable force, capable of challenging or even surpassing the U.S. military in certain categories, particularly in a conflict close to China’s shores. However, a contentious report by the Washington-based RAND Corporation challenges this perception, arguing that political considerations within the ruling Communist Party could significantly hamper the PLA’s effectiveness in battle, especially against a “peer adversary such as the US.”

Timothy Heath, a long-time China expert with RAND, asserts that “The PLA remains fundamentally focused on upholding Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule rather than preparing for war.” He posits that the military modernization gains are “designed first and foremost to bolster the appeal and credibility of CCP rule,” making a large-scale war less likely. This perspective suggests that the impressive military buildup serves internal political stability more than external aggression.

Heath cites several examples of political objectives potentially undermining military readiness. Up to 40% of PLA training time is reportedly spent on political topics, leading to a “trade-off in time that could be spent mastering the essential skills for combat operations.” Moreover, PLA units operate under a “divided command system” where commanding officers are accompanied by political commissars who prioritize party loyalty. This dual leadership “reduces the ability of commanders to respond flexibly and rapidly to emerging situations,” raising critical questions about the PLA’s actual preparedness for modern warfare.

Military equipment: Modernization of the People’s Liberation Army

Categories: All articles needing additional references, All articles that may contain original research, All articles with unsourced statements, Articles needing additional references from December 2007, Articles needing additional references from December 2022

Summary: The military modernization program of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) which began in the late 1970s had three major focuses. First, under the political leadership of 3rd paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, the military became disengaged from civilian politics and, for the most part, resumed the political quiescence that characterized its pre-Cultural Revolution role. Deng reestablished civilian control over the military by appointing his supporters to key military leadership positions, by reducing the scope of the PLA’s domestic non-military role, and by revitalizing the party political structure and ideological control system within the PLA.

Second, modernization required the reform of military organization, doctrine, education and training, and personnel policies to improve combat effectiveness in combined-arms warfare. Among the organizational reforms that were undertaken were the creation of the Central Military Commission (CMC) of Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the streamlining and reduction of superfluous PLA forces, civilianization of many PLA units, reorganization of military regions, formation of group armies, and enactment of the new Military Service Law in 1984. Doctrine, strategy, and tactics were revised under the rubric of “people’s war under modern conditions,” which envisaged a forward defense at selected locations near China’s borders, to prevent attack on Chinese cities and industrial sites, and emphasized operations using combined-arms tactics. Reforms in education and training emphasized improving the military skills and raising the education levels of officers and troops and conducting combined-arms operations. New personnel policies required upgrading the quality of PLA recruits and officer candidates, improving conditions of service, changing promotion practices to stress professional competence, and providing new uniforms and insignia.

The third focus of military modernization was the transformation of the defense establishment into a system capable of independently maintaining a modern military force. As military expenditures remained relatively constant, reforms concentrated on reorganizing the defense research and development and industrial base to integrate civilian and military science and industry more closely. Foreign technology was used selectively to upgrade weapons. Defense industry reforms also resulted in China’s entry into the international arms market and the increased production of civilian goods by defense industries. The scope of PLA economic activities was reduced, but the military continued to participate in infrastructure development projects and initiated a program to provide demobilized soldiers with skills useful in the civilian economy.

As of 2015, China focuses on domestic weapon designs and manufacturing, while still importing certain military products from Russia such as jet engines. China decided to become independent in its defense sector and become competitive in global arms markets: its defense sector is rapidly developing and maturing. Gaps in certain capability remain—most notably in the development of some sophisticated electronic systems and sufficiently reliable and powerful propulsion systems—but China’s defense industry is now producing warships and submarines, land systems and aircraft that provide the Chinese armed forces with a capability edge over most militaries operating in the Asia-Pacific. Where indigenous capability still falls short, China procures from Russia and, until local industry eventually bridges the gap, it hopes that quantity will overcome quality. China’s 2015 Defense White Paper called for “independent innovation” and the “sustainable development” of advanced weaponry and equipment.

According to The National Interest, as of 2015, Chinese industry can still learn much from Russia, but in many areas it has caught up with its model. The vibrancy of China’s tech sector suggests that Chinese military technology will most likely leap ahead of Russian tech in the next decade.

Modernization efforts were originally planned to be completed by 2049. However, following the 19th CCP National Congress in 2017, CCP General Secretary and CMC chairman Xi Jinping announced modernization to be completed by 2035. China watchers regard the revised timeline as a sign for the success of the reforms, although issues and shortfalls still remain, specifically in the areas of capability development and combat readiness of the Air Force as well as the infantry.

Get more information about: Modernization of the People’s Liberation Army

11. **The Unprecedented Military Purges Within the PLA**Adding to the questions surrounding the PLA’s true combat readiness is a recent and “unprecedented” wave of purges within its senior leadership. Since the 20th National Party Congress in October 2022, more than 20 senior PLA officers, including members from all four services, have been removed or disappeared from public view. Most strikingly, three of the six uniformed members of the party’s Central Military Commission (CMC)—the top body overseeing the armed forces—have been dismissed in a remarkably short period.

This includes former Defense Minister Li Shangfu, removed in October 2023 and expelled from the CCP; Miao Hua, director of the CMC’s Political Work Department, suspended for “serious violations of discipline”; and reportedly, He Weidong, the second-ranked vice chair, who has not appeared in public since early March. The unusual nature of these purges is amplified by the fact that all three generals had been promoted by Xi Jinping himself, appointed to the CMC in 2022, and some were even considered part of a “Fujian faction” with close ties to the Chinese leader.

These high-profile dismissals carry significant implications for the PLA’s readiness. Observers suggest that such purges are likely to “slow some weapons modernization programs, disrupt command structures and decision-making, and weaken morale.” In the near to medium term, this degradation of capabilities could force Beijing to “exercise greater caution before pursuing large-scale military operations, such as an amphibious assault on Taiwan,” even as it continues to apply pressure through aerial activity and naval patrols around the island.

Military equipment: People’s Liberation Army

Name: People’s Liberation Army

NativeName: 中国人民解放军

Caption: Emblem of the People’s Liberation Army

Caption2: Flag of the People’s Liberation Army

Motto: Serve the People

Founded: [object Object]

CurrentForm: [object Object]

Branches:

Headquarters: August First Building,Fuxing Road, Beijing,Haidian, Beijing

Website: Official URL

CommanderInChief: Central Military Commission (China)

Child: true

Label1: Supreme Military Command of the People’s Republic of China

Data1: Flagicon image,Xi Jinping,Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission

CommanderInChiefTitle: Governing body

ChiefMinister: Flagdeco,Jiang (rank),Dong Jun

ChiefMinisterTitle: Minister of National Defense (China)

Minister: Flagdeco,Jiang (rank),Miao Hua

MinisterTitle: Political Work Department of the Central Military Commission

ChiefOfStaff: Flagdeco,Jiang (rank),Liu Zhenli (general)

ChiefOfStaffTitle: Joint Staff Department (China)

Commander: Flagicon image,Jiang (rank),Zhang Shengmin

CommanderTitle: Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Central Military Commission

Age: 18

Conscription: Conscription_in_China

Active: Sfn

Ranked: 1st

Reserve: 510,000 (2025)

Amount: List of countries by military expenditures

PercentGdp: 1.7% (2024)

DomesticSuppliers: blist

ForeignSuppliers: {{USSR

Imports: Currency

Exports: Currency

History: History of the People’s Liberation Army,Modernization of the People’s Liberation Army,List of Chinese wars and battles,List of wars involving the People’s Republic of China

Ranks: Ranks of the People’s Liberation Army Ground Force,Ranks of the People’s Liberation Army Navy,Ranks of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force

Title: Chinese People’s Liberation Army

T: 中國人民解放軍

S: 中国人民解放军

L: “China People Liberation Army”

P: Zhōngguó Rénmín Jiěfàngjūn

Tp: Jhong-guó Rén-mín Jiě-fàng-jyun

W: tone superscript

Y: Jūng-gwok Yàhn-màhn Gáai-fong-gwān

J: zung1 gwok3 jan4 man4 gaai2 fong3 gwan1

Bpmf: ㄓㄨㄥ ㄍㄨㄛˊ ㄖㄣˊ ㄇㄧㄣˊ ㄐㄧㄝˇ ㄈㄤˋ ㄐㄩㄣ

Mi: IPAc-cmn

Ci: IPAc-yue

Order: st

Categories: 1927 establishments in China, All articles containing potentially dated statements, All articles with unsourced statements, Articles containing Chinese-language text, Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2024

Summary: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is the military of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). It consists of four services—Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force—and four arms—Aerospace Force, Cyberspace Force, Information Support Force, and Joint Logistics Support Force. It is led by the Central Military Commission (CMC) with its chairman as commander-in-chief.

The PLA can trace its origins during the Republican era to the left-wing units of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), when they broke away in 1927 in an uprising against the nationalist government as the Chinese Red Army before being reintegrated into the NRA as units of New Fourth Army and Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The two NRA communist units were reconstituted as the PLA in 1947. Since 1949, the PLA has used nine different military strategies, which it calls “strategic guidelines”. The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993. Politically, the PLA and the paramilitary People’s Armed Police (PAP) have the largest delegation in the National People’s Congress (NPC); the joint delegation currently has 281 deputies—over 9% of the total—all of whom are CCP members.

The PLA is not a traditional nation-state military. It is a part, and the armed wing, of the CCP and controlled by the party, not by the state. The PLA’s primary mission is the defense of the party and its interests. The PLA is the guarantor of the party’s survival and rule, and the party prioritizes maintaining control and the loyalty of the PLA. According to Chinese law, the party has leadership over the armed forces and the CMC exercises supreme military command; the party and state CMCs are practically a single body by membership. Since 1989, the CCP general secretary has also been the CMC Chairman; this grants significant political power as the only member of the Politburo Standing Committee with direct responsibilities for the armed forces. The Ministry of National Defense has no command authority; it is the PLA’s interface with state and foreign entities and insulates the PLA from external influence.

Today, the majority of military units around the country are assigned to one of five theatre commands by geographical location. The PLA is the world’s largest military force (not including paramilitary or reserve forces) and has the second largest defence budget in the world. China’s military expenditure was US$314 billion in 2024, accounting for 12 percent of the world’s defence expenditures. It is also one of the fastest modernizing militaries in the world, and has been termed as a potential military superpower, with significant regional defence and rising global power projection capabilities.

In addition to wartime arrangements, the PLA is also involved in the peacetime operations of other components of the armed forces. This is particularly visible in maritime territorial disputes where the navy is heavily involved in the planning, coordination and execution of operations by the PAP’s China Coast Guard.

Get more information about: People’s Liberation Army

12. **Historical Precedents for Chinese Military Action**Despite concerns about internal readiness issues and the disruptive impact of recent purges, it is crucial to consider China’s historical approach to military engagement. Beijing has a track record of initiating conflicts even when domestic economic and political conditions appeared unfavorable, and even when its military was arguably not fully prepared. This historical pattern suggests that leadership decisions on military action may not always align with Western analyses of optimal conditions for warfare.

For instance, in 1950, Chinese forces intervened in the Korean War in support of Pyongyang, despite China’s economy and society having been “devastated by years of civil war.” Similarly, in 1962, the PLA attacked India, even after its most senior military officer had been purged for questioning Mao Zedong’s “disastrous Great Leap Forward.” These instances highlight a willingness to project force regardless of internal stability or military perfection.

A further example occurred in 1979, when Beijing dispatched an “ill-prepared PLA to Vietnam,” where Chinese troops reportedly “suffered significant losses for limited political gains.” These historical precedents serve as a sober reminder that while the PLA’s current readiness challenges and internal purges might suggest caution, Chinese leaders have, in the past, chosen to pursue war when they deemed it politically necessary, even at considerable cost and without ideal military preparedness.

Military equipment: Affirmative action in China

Title: Affirmative action of ethnic minorities in China

C: 优惠政策

T: 優惠政策

P: Yōuhuì zhèngcè

L: Preferential policy

Categories: Affirmative action in Asia, All articles with unsourced statements, Articles containing Chinese-language text, Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text, Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

Summary: In the People’s Republic of China, the government had instated affirmative action policies for ethnic minorities called preferential policy (simplified Chinese: 优惠政策; traditional Chinese: 優惠政策; pinyin: Yōuhuì zhèngcè) or bonus point for minority ethnic groups (simplified Chinese: 少数民族加分; traditional Chinese: 少數民族加分; pinyin: Shǎoshù mínzú jiāfēn in College Entrance Examination) when it began in 1949 and still had impact until today. The policies give preferential treatment to ethnic minorities in China. For example, minority ethnic groups in China were not subjected to its well-publicized (former) one-child policy. Three principles are the basis for the policy: equality for national minorities, territorial autonomy, and equality for all languages and cultures.

Get more information about: Affirmative action in China

Read more about: Some Analytical Insights into Ukraine’s Evolving Air Strategy: Precision Strikes, Tactical Revelations, and Geopolitical Shifts

13. **The “Human Factor” in PLA Readiness: Personnel and Corruption Challenges**While the PLA has undeniably made significant strides in acquiring advanced weaponry, from its Type 055 destroyers to hypersonic weapons, questions persist regarding the human element critical to operating such sophisticated systems. Collin Koh, a research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, points out that building high-tech warships may be “easier than crewing them.” Modern warships demand young sailors capable of complex tasks, requiring extensive training that differs significantly from traditional infantry roles.

Koh highlights the challenge: “The army could likely assimilate someone from the countryside … who might not get a lot of education … and train him up to be an infantryman. But if you want to train somebody who is able to man the controls in the combat information center in the warship, fire a missile and to maintain a missile, that requires a bit more.” This underscores a potential gap between China’s advanced hardware and its capacity to recruit, train, and retain the highly skilled personnel needed to operate it effectively.

Compounding these personnel challenges is the persistent issue of corruption within the PLA. A Pentagon report from December indicated that a widespread anti-corruption campaign targeting senior military and government levels is “impeding Xi’s defense buildup.” A senior U.S. defense official noted that corruption “really has posed great risks to the political reliability and ultimately the operational capability of the PLA,” suggesting that deeply entrenched issues within the military hierarchy could undermine its overall effectiveness, despite the outward appearance of modernization.

Military equipment: HC-130J Combat King

Contractor: Lockheed Aircraft Corp.

Service: United States Air Force

Power Plant: Four Rolls Royce AE2100D3 turboprop engines

Payload: 35,000 pounds (15,875 kilograms)

Speed: 316 knots indicated air speed at sea level

Range: beyond 4,000 miles (3,478 nautical miles)

Armament: countermeasures/flares, chaff

Basic Crew: Three officers (pilot, co-pilot, combat system officer) and two enlisted loadmasters

Categories: Air Force Aircraft, Air Force Equipment, Military Aircraft, Special Mission Aircraft, Tanker Aircraft

Get more information about: HC-130J Combat King

14. **Re-evaluating Chinese Military Intentions and Readiness Beyond Taiwan**Discussions about Chinese military readiness often quickly pivot to the prospect of an invasion of Taiwan, with U.S. intelligence estimating Xi’s instruction for the PLA to be ready by 2027. However, some analysts, like Timothy Heath of RAND, argue against solely framing readiness through this lens. Heath points out that Chinese leaders “have made no speeches that glorify war, advocate for war, or otherwise characterize war as inevitable or desirable,” and that “China’s military has not even published a study on how it might occupy and control Taiwan.

Heath suggests that China’s military modernization gains “are not designed to conquer Taiwan through military attack” but rather “designed to help the PLA more effectively carry out its longstanding mission of upholding CCP rule.” In this view, new warships and stealth fighter jets serve as impressive symbols for the public, thereby “making controlling society easier.” Drew Thompson, a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, concurs, noting that “Politics being primary means propaganda is more important than the military outcome.”

However, other experts caution against dismissing the PLA’s capabilities as mere showmanship. While a full-scale invasion is one possibility, Collin Koh emphasizes that Beijing’s use of force could be “calibrated to suit its political needs,” ranging from a blockade to airstrikes, or even a continuation of relentless political pressure and constant military presence around Taiwan. Ultimately, while the “human factor” and internal issues exist, “any military planner in the region is not going to just dismiss the PLA as a paper tiger,” and the question of whether China “could start a war and fight it” remains distinct from how “victory” might be defined.

Military equipment: China–United States relations

Envoytitle1: List of ambassadors of China to the United States

Envoy1: Xie Feng (diplomat)

Envoytitle2: List of ambassadors of the United States to China

Envoy2: David Perdue

Mission1: Embassy of China, Washington, D.C.

Mission2: Embassy of the United States, Beijing

Map: China USA Locator.svg

Categories: All Wikipedia articles in need of updating, All Wikipedia articles written in American English, All articles lacking reliable references, All articles that may be too long, All articles with dead external links

Summary: The relationship between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the United States of America (USA) is the most important bilateral relationship in the world. It has been complex and at times tense since the establishment of the PRC and the retreat of the government of the Republic of China to Taiwan in 1949. Since the normalization of relations in the 1970s, the US–China relationship has been marked by persistent disputes including China’s economic policies, the political status of Taiwan and territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Despite these tensions, the two nations have significant economic ties and are deeply interconnected, while also engaging in strategic competition on the global stage. As of 2025, China and the United States are the world’s second-largest and largest economies by nominal GDP, as well as the largest and second-largest economies by GDP (PPP) respectively. Collectively, they account for 44.2% of the global nominal GDP, and 34.7% of global PPP-adjusted GDP.

One of the earliest major interactions between the United States and China was the 1845 Treaty of Wangxia, which laid the foundation for trade between the two countries. While American businesses anticipated a vast market in China, trade grew gradually. In 1900, Washington joined the Empire of Japan and other powers of Europe in sending troops to suppress the xenophobic Boxer Rebellion, later promoting the Open Door Policy to advocate for equal trade opportunities and discourage territorial divisions in China. Despite hopes that American financial influence would expand, efforts during the Taft presidency to secure US investment in Chinese railways were unsuccessful. President Franklin D. Roosevelt supported China during the Second Sino-Japanese War, aligning with the Republic of China (ROC) government, which had formed a temporary alliance with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to fight the Japanese. Following Japan’s defeat, the Chinese Civil War resumed, and US diplomatic efforts to mediate between the Nationalists and Communists ultimately failed. The Communist forces prevailed, leading to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, while the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan.

Relations between the US and the new Chinese government quickly soured, culminating in direct conflict during the Korean War. The US-led United Nations intervention was met with Chinese military involvement, as Beijing sent millions of Chinese fighters to prevent a US-aligned presence on its border. For decades, the United States did not formally recognize the PRC, instead maintaining diplomatic relations with the ROC based in Taiwan, and as such blocked the PRC’s entry into the United Nations. However, shifting geopolitical dynamics, including the Sino-Soviet split, the winding down of the Vietnam War, as well as of the Cultural Revolution, paved the way for US President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, ultimately marking a sea change in US–China relations. On 1 January 1979, the US formally established diplomatic relations with the PRC and recognized it as the sole legitimate government of China, while maintaining unofficial ties with Taiwan within the framework of the Taiwan Relations Act, an issue that remains a major point of contention between the two countries to the present day.

Every US president since Nixon has toured China during their term in office, with the exception of Jimmy Carter and Joe Biden. The Obama administration signed a record number of bilateral agreements with China, particularly regarding climate change, though its broader strategy of rebalancing towards Asia created diplomatic friction. The advent of Xi Jinping’s general secretaryship would prefigure a sharp downturn in these relations, which was then further entrenched upon the election of President Donald Trump, who had promised an assertive stance towards China as a part of his campaign, which began to be implemented upon his taking office. Issues included China’s militarization of the South China Sea, alleged manipulation of the Chinese currency, and Chinese espionage in the United States. The Trump administration would label China a “strategic competitor” in 2017. In January 2018, Trump launched a trade war with China, while also restricting American companies from selling equipment to various Chinese companies linked to human rights abuses in Xinjiang, among which included Chinese technology conglomerates Huawei and ZTE. The US revoked preferential treatment towards Hong Kong after the Beijing’s enactment of a broad-reaching national security law in the city, increased visa restrictions on Chinese students and researchers, and strengthened relations with Taiwan. In response, China adopted “wolf warrior diplomacy”, countering US criticisms of human rights abuses. By early 2018, various geopolitical observers had begun to speak of a new Cold War between the two powers. On the last day of the Trump administration in January 2021, the US officially classified the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang as a genocide.

Following the election of Joe Biden in the 2020 United States presidential election, tensions between the two countries remained high. Biden identified strategic competition with China as a top priority in his foreign policy. His administration imposed large-scale restrictions on the sale of semiconductor technology to China, boosted regional alliances against China, and expanded support for Taiwan. However, the Biden administration also emphasized that the US sought “competition, not conflict”, with Biden stating in late 2022 that “there needs to not be a new Cold War”. Despite efforts at diplomatic engagement, US-China trade and political relations have reached their lowest point in years, largely due to disagreements over technology and China’s military growth and human rights record. In his second term, President Donald Trump sharply escalated the trade war with China, raising baseline tariffs on Chinese imports to an effective 145%, prior to negotiating with China on 12 May 2025 a reduction in the tariff rate to 30% for 90 days while further negotiations take place.

Get more information about: China–United States relations

As the intricate dance of power in the Indo-Pacific continues, the F-35 stands at a curious juncture, its technological prowess matched by unexpected operational hurdles and a questioning international appeal. Simultaneously, China’s military, while rapidly modernizing, grapples with its own internal complexities, from sophisticated anti-stealth ambitions to the profound impact of political purges and the enduring challenge of human capital. The interplay of these forces—technological advancement, strategic vulnerabilities, and the very real human and political dimensions of military power—paints a dynamic and often unpredictable picture. The future of regional stability hinges not just on the capabilities of the jets in the sky, but on the opaque intentions and evolving readiness of the powers on the ground, creating a geopolitical landscape ripe with both tension and uncertainty.