The vast and intricate network of roads and intersections across the United States is a lifeline for its over 340 million residents, connecting communities and facilitating commerce. Understanding the inherent challenges within this system is crucial for ensuring public safety and efficient transportation. While specific “crash data” revealing pinpointed dangerous locations is beyond the scope of the information provided for this analysis, we can delve into the foundational geographic, climatic, and historical elements that profoundly influence the complexity, maintenance, and inherent conditions of America’s roadways.

The unique tapestry of the United States, from its expansive land area to its varied climates and diverse populations, presents an array of considerations for transportation infrastructure. These underlying factors contribute significantly to the operational realities of American roads, creating environments where conditions can range dramatically and demand constant adaptation in design and management. By examining these broad influences, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the multifaceted nature of road travel across this dynamic nation.

This in-depth exploration will identify key characteristics of the American landscape and its development, drawing exclusively from the provided context. Each aspect offers insight into the foundational elements that shape the country’s extensive road network, providing a framework for understanding the diverse challenges faced in maintaining safe and efficient travel across the contiguous states, Alaska, and Hawaii.

1. **The United States’ Vast Geographic Expanse and Diverse Topography**The United States, being “the world’s third-largest country by total area behind Russia and Canada,” immediately presents a monumental task for infrastructure development and uniform maintenance. This immense scale necessitates a road network that spans millions of square miles, connecting regions with dramatically different geological characteristics and population densities. The sheer distances involved create inherent complexities in managing a cohesive national transportation system.

Geographic diversity is a hallmark of the nation, ranging from the relatively flat “coastal plain of the Atlantic seaboard” to the undulating “inland forests and rolling hills in the Piedmont plateau region.” These varied landforms directly influence road construction, requiring diverse engineering solutions from simple grading to complex earthworks. Each type of terrain demands tailored design and construction practices to ensure both durability and traveler safety.

Moving westward, the landscape evolves from the expansive “grasslands of the Midwest” to more challenging natural features. The presence of “the Rocky Mountains,” extending “north to south across the country,” and the “rocky Great Basin and the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave deserts” introduces significant obstacles. These features require roads to navigate through steep inclines, deep valleys, and arid conditions, each presenting unique engineering and maintenance challenges that impact long-term road integrity.

The context also highlights features like the “Grand Canyon in Arizona, carved by the Colorado River,” which exemplifies how profound natural formations dictate routing and demand substantial infrastructure projects like bridges and tunnels. Furthermore, the inclusion of “Alaska’s Denali” as the highest peak and “active volcanoes in Alaska” underscores the extreme environments where roads must contend with geological instability and seismic activity. This vastness and topographical range ensure that no single approach to road development or safety can apply universally across the nation.

Read more about: Your Ultimate Guide to the 15 Best States for Off-Roading and Unrestricted Public Land Access

2. **Extensive Variety in Climate Zones Nationwide**Due to its “large size and geographic variety,” the United States encompasses “most climate types,” a critical factor that significantly influences the design, durability, and maintenance of its road infrastructure. This climatic diversity means that roads across the country are subjected to a wide array of environmental stressors, dictating localized construction materials and management strategies.

East of the 100th meridian, the climate transitions “from humid continental in the north to humid subtropical in the south.” Humid continental regions endure harsh winters with extensive freeze-thaw cycles and heavy snowfall, which contribute significantly to pavement cracking, pothole formation, and reduced visibility. Conversely, the humid subtropical south contends with high temperatures, intense rainfall, and tropical storm impacts, leading to rapid asphalt degradation, flooding, and erosion, all of which compromise road integrity.

In the western Great Plains, conditions become “semi-arid,” characterized by lower precipitation but susceptibility to dust storms that can severely impair visibility and require specialized road surfacing to mitigate erosion. Further west, “many mountainous areas of the American West have an alpine climate,” bringing extreme cold, heavy snow, and persistent ice. These conditions necessitate robust snow removal, de-icing operations, and specialized engineering to ensure routes remain passable and safe for travelers.

Coastal regions also present distinct climatic challenges. “Mediterranean in coastal California” and “oceanic in coastal Oregon, Washington, and southern Alaska” describe areas with significant rainfall and persistent moisture, accelerating wear on road surfaces and contributing to issues like hydroplaning. Meanwhile, “most of Alaska is subarctic or polar,” where roads must be built on or around permafrost, requiring specialized engineering to prevent subsidence and structural failure from thawing and freezing ground.

Finally, the mention of “Hawaii, the southern tip of Florida and U.S. territories in the Caribbean and Pacific are tropical.” These areas experience intense humidity, torrential rains, and are frequently impacted by hurricanes. Such conditions can cause severe damage to roads through flooding, landslides, and wind-borne debris, highlighting the localized and highly varied nature of climatic impacts on America’s extensive road network and demanding adaptive infrastructure solutions.

Read more about: America’s Enduring Story: Unveiling 13 Defining Pillars of the United States’ Identity and Impact

3. **High Frequency of Extreme Weather Incidents**The United States stands out globally for receiving “more high-impact extreme weather incidents than any other country.” This susceptibility to severe weather poses a continuous and evolving threat to the nation’s road infrastructure, directly affecting both the physical condition of roadways and the safety of travel. These incidents can quickly render vast sections of the road network impassable or highly hazardous, demanding rapid response and significant resources.

Coastal regions, particularly “States bordering the Gulf of Mexico, are prone to hurricanes.” These powerful storms bring not only destructive winds but also storm surges and torrential rainfall, which can cause widespread flooding, severe erosion, and structural damage to bridges and roads. Such events lead to prolonged closures, isolation of communities, and immense repair costs, underscoring the vulnerability of coastal transportation arteries to these formidable natural forces.

In the central United States, “most of the world’s tornadoes occur in the country, mainly in Tornado Alley.” Tornadoes are capable of causing localized but catastrophic damage, including tearing up pavement, scattering large debris, and felling utility poles directly onto roads. The unpredictable nature and intense destructive power of tornadoes present immediate and extreme hazards to drivers and severely disrupt road functionality in affected areas, requiring urgent assessments and emergency repairs.

Beyond immediate destructive events, the context notes that “due to climate change in the country, extreme weather has become more frequent in the U.S. in the 21st century, with three times the number of reported heat waves compared to the 1960s.” Increased and more intense heat waves contribute to the accelerated degradation of road surfaces. High temperatures can cause asphalt to soften, crack, and rut, leading to uneven driving surfaces, reduced pavement lifespan, and increased maintenance cycles.

Furthermore, “since the 1990s, droughts in the American Southwest have become more persistent and more severe.” While seemingly less direct, prolonged droughts can lead to soil contraction and instability, which can undermine road foundations and bridge supports, potentially causing cracking or subsidence. The cumulative effect of hurricanes, tornadoes, heat waves, and droughts presents a complex and growing challenge for maintaining a resilient and safe road network across the diverse landscapes of the United States.

Read more about: America’s Manufacturing Resurgence Will Be Powered by These Robots: A Look at the Nation’s Enduring Capacity for Innovation

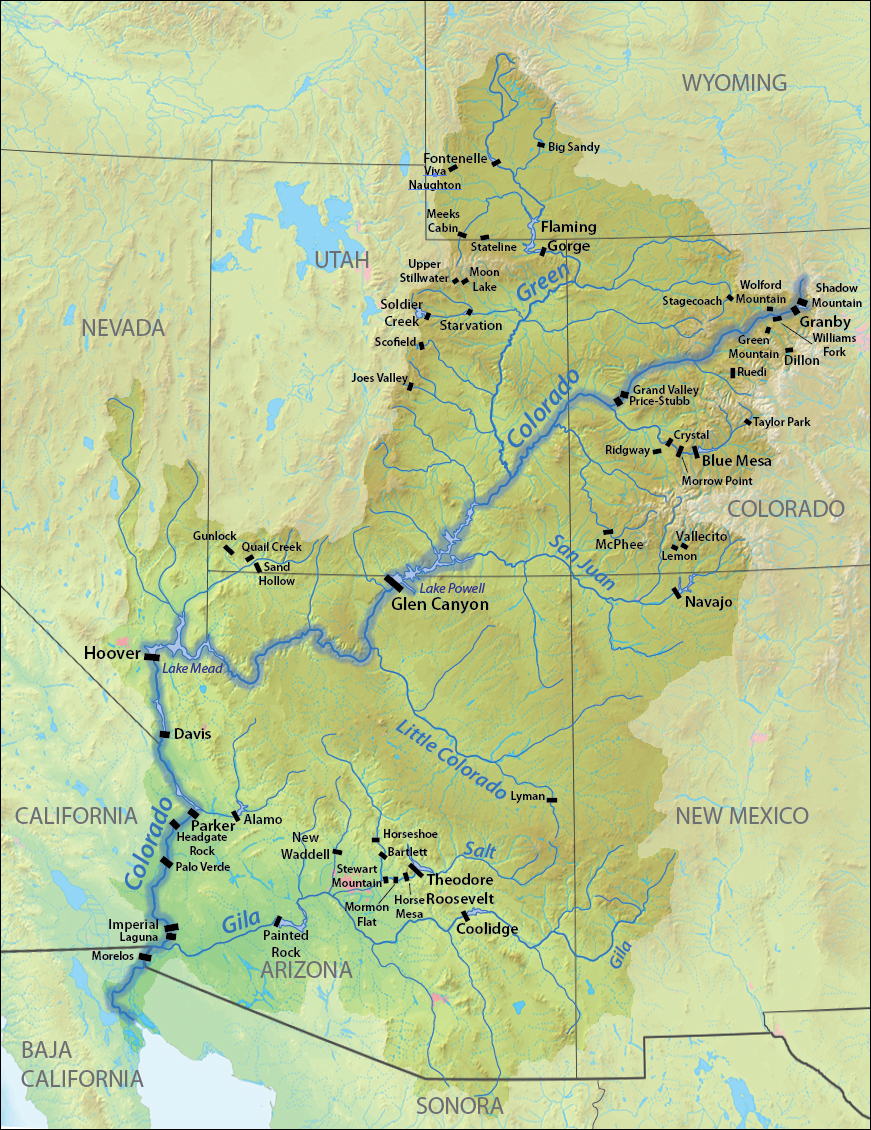

4. **Prominence of Major River Systems and Waterways**The United States is characterized by extensive river systems, which serve as both natural boundaries and vital corridors, profoundly influencing the layout and engineering of its road infrastructure. Central to this network is the “Mississippi River System, the world’s fourth-longest river system,” which flows “predominantly north–south through the center of the country.” This immense river, along with countless other major waterways, necessitates a comprehensive approach to road construction.

The presence of such vast river systems mandates the construction of an intricate array of bridges, which are indispensable components of the national road network. These structures are not merely crossings but complex engineering marvels designed to withstand continuous traffic loads, varying environmental conditions, and the powerful forces of flowing water. The sheer number of bridges and their ongoing maintenance represent significant logistical and financial challenges, directly impacting the continuity and safety of road travel.

Major rivers often act as significant geographical barriers, determining the most feasible and efficient locations for road crossings. These crossing points can become critical chokepoints, particularly in densely populated urban areas, leading to traffic congestion and delays. The structural integrity and operational status of these bridges are therefore paramount; any damage or closure can have cascading effects, disrupting regional and national transportation flows and commerce.

Moreover, the dynamic nature of these waterways directly impacts adjacent road infrastructure. Fluctuations in river levels, especially during periods of heavy precipitation or snowmelt, can lead to widespread flooding of low-lying roads and cause significant erosion of embankments. Such events render routes impassable, necessitating costly and time-consuming repairs and diversions, thereby highlighting the constant interplay between natural hydrological cycles and engineered transportation routes.

Consequently, the prominent role of major river systems underscores the intricate relationship between America’s natural environment and its transportation arteries. The challenge extends beyond merely building roads *over* water; it involves integrating these crossings into a resilient and adaptable network capable of enduring the powerful and ever-changing conditions of some of the world’s largest rivers, ensuring safe and reliable passage for all travelers and goods.

Read more about: Cracking the Code: The Ingenious Reasons Why America’s Major Cities Rose in Their Iconic Spots

5. **The Impact of Mountain Ranges and Deserts on Infrastructure**America’s diverse topography includes formidable mountain ranges and expansive deserts, each presenting distinct and significant challenges for the construction, maintenance, and safety of its road infrastructure. West of the Great Plains, “the Rocky Mountains… extend north to south across the country, peaking at over 14,000 feet (4,300 m) in Colorado.” These natural barriers require highly specialized engineering solutions for road development.

Building roads through mountainous terrain involves navigating steep grades, sharp curves, and the constant threat of geological hazards such as landslides, rockfalls, and avalanches. Construction efforts in these regions demand extensive excavation, tunneling, and the installation of retaining structures, making such projects both capital-intensive and technically complex. The high altitudes also expose roads to severe weather, including heavy snowfall and ice, which limit accessibility and necessitate rigorous winter maintenance operations, directly impacting driving safety and route reliability.

Further to the west, the landscape transitions dramatically into “the rocky Great Basin and the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave deserts.” These arid environments pose a different set of challenges for road infrastructure. Extreme heat in these regions accelerates the degradation of road materials, causing asphalt to soften, crack, and deform. The scarcity of readily available water and suitable construction aggregates also increases the logistical complexity and cost of road projects in these remote areas.

Desert roads are also particularly vulnerable to environmental phenomena such as sandstorms, which can drastically reduce visibility to near zero and deposit large quantities of sand and debris on roadways. This necessitates frequent clearing operations and impacts travel safety. The often vast and remote nature of many desert routes also means longer distances between services, fewer emergency response resources, and elevated risks associated with vehicle breakdowns in extreme and isolated conditions.

Even iconic natural landmarks, such as the “Grand Canyon in Arizona,” although a significant tourist destination, illustrate how profound geological formations dictate transportation routes. Roads must either skillfully circumnavigate these massive natural obstacles or be engineered with remarkable ingenuity to provide access, often at considerable expense and with significant environmental considerations. The combined influence of towering mountain ranges and expansive deserts fundamentally shapes the design, construction, and operational safety of a substantial portion of the American road network, requiring continuous adaptation and resilience.

Read more about: America’s Enduring Story: Unveiling 13 Defining Pillars of the United States’ Identity and Impact

6. **The Evolution of Governance and its Impact on Infrastructure Development**America’s transportation backbone has been profoundly shaped by its evolving governance structures, starting from early colonial self-rule. The Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut established crucial precedents for local representative self-governance and constitutionalism. These early forms of administration laid the groundwork for how local communities would eventually approach their own infrastructure needs.

British administration of the original Thirteen Colonies, through Crown-appointed governors, also played a role. While local governments held elections, oversight from afar likely influenced the prioritization and funding of inter-colonial routes, which were essential for trade and communication. The eventual “clashes with the British Crown over taxation and lack of parliamentary representation” fueled the American Revolution, leading to a desire for self-determination in all facets, including public works.

The transition from the decentralized Articles of Confederation (1781-1789) to the U.S. Constitution (1789) marked a pivotal shift. The Constitution established a federal republic with a system of checks and balances, creating a more centralized government with greater capacity for large-scale projects. Federalism grants “substantial autonomy to the 50 states,” allowing for diverse approaches to road policy and funding, which contributes to varied conditions nationwide.

The U.S. Congress, as the legislative branch, holds significant powers relevant to infrastructure. It “makes federal law, declares war, approves treaties,” and has “the power of the purse,” all of which can directly or indirectly fund, authorize, or regulate transportation initiatives. Congressional oversight of the executive branch also ensures accountability in how federal resources are allocated and projects managed, influencing road quality and safety standards across states.

The ongoing role of federal agencies, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, illustrates the complex governance landscape. These bodies address environmental issues and protect species, which can influence road planning, construction, and expansion. Such regulations, alongside state-level autonomy, create a dynamic framework for infrastructure development that balances national objectives with local needs and environmental considerations.

Read more about: Midway City: 14 Critical Insights into an Unincorporated Community’s Defining Features and Persistent Struggles

7. **Major Historical Shifts and Their Transportation Implications**America’s territorial expansion fundamentally dictated the growth and layout of its road networks. The concept of “manifest destiny” in the late 18th century spurred westward movement, necessitating new routes for settlers, goods, and communication. This initial push laid rudimentary foundations for future roadways, connecting newly settled areas to established eastern regions.

A landmark event was the “Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France,” which “nearly doubled the territory of the United States.” This massive acquisition immediately created an immense need for exploration, mapping, and the eventual development of transportation corridors to integrate these new lands. Subsequent territorial gains, including Florida in 1819, the Oregon Treaty in 1846, and the Mexican Cession in 1848 (which added Texas, New Mexico, California, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah), continually expanded the nation’s footprint and the corresponding demand for infrastructure.

The processes of expansion also involved significant and often tragic policies impacting indigenous populations. The “Indian Removal Act of 1830,” a key policy of President Andrew Jackson, led to events like the “Trail of Tears.” This forced displacement of Native Americans, while a humanitarian crisis, also involved the movement of tens of thousands across vast distances. Such movements, by necessity, utilized and sometimes established rudimentary pathways that later influenced the routing of settler roads and trails, highlighting the complex origins of some American thoroughfares.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) marked another profound historical shift with lasting transportation implications. The “North–South division over slavery” culminated in a conflict that ravaged parts of the nation. Post-war reunification and Reconstruction efforts likely involved rebuilding damaged infrastructure and re-establishing transport links critical for economic recovery and national cohesion, though specifics beyond general context are not provided. The need to connect a reunited nation spurred subsequent investment in national transportation networks.

The purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 and the annexation of Hawaii in 1898, along with other territories like Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, extended the reach of American governance. While many of these are overseas, they underscored a broader national interest in connectivity, which for the contiguous states, reinforced the need for a robust and integrated domestic transportation system to support a growing global power.

Read more about: Why Your Grocery Bill Stays Stubbornly High: An In-Depth Look at Sticky Inflation

8. **Demographic Changes and Urbanization’s Influence on Road Networks**From its earliest days, demographic shifts have continuously reshaped the demand for and design of America’s road infrastructure. Following European colonization, the “colonial population grew rapidly from Maine to Georgia,” steadily “eclipsing Native American populations” by the 1770s. This initial population density and expansion along the eastern seaboard created the first urgent need for inter-settlement roads and pathways to facilitate trade and communication.

The 19th century was characterized by significant internal migrations, notably the “westward expansion” where “American settlers began to expand westward in larger numbers.” This movement created new communities far from existing infrastructure, demanding the establishment of new roads and trails to connect pioneers to supplies, markets, and administrative centers. The “California gold rush of 1848–1849” further accelerated a “huge migration of white settlers to the Pacific coast,” rapidly increasing the need for Pacific Coast road connectivity.

Following the Civil War and throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States experienced “an unprecedented stream of immigrants.” “From 1865 through 1917, 24.4 million from Europe” arrived, with many settling in major East Coast cities like New York. Concurrently, the “Great Migration” saw “millions of African Americans left the rural South for urban areas in the North.” These massive influxes into urban centers dramatically increased population density and the need for robust city road networks, public transit, and improved arterial routes to manage burgeoning populations and commerce.

Post-World War II, “the U.S. experienced economic growth, urbanization, and population growth.” This period saw a significant rise in suburban living, leading to a greater reliance on personal automobiles. This demographic shift directly drove the need for extensive highway systems to connect growing suburban populations with urban employment centers. The expansion of these networks became paramount to support the new patterns of daily life and work.

Further societal changes in the 1970s, including “a societal shift in the roles of women” leading to “a large increase in female paid labor participation,” also amplified demand on transportation infrastructure. With more individuals commuting to work, road capacity became a critical consideration. These cumulative demographic transformations have consistently underscored the need for adaptable and expansive road networks to serve a growing and increasingly mobile population.

9. **Economic Cycles and Technological Advancements Shaping Road Investment**The trajectory of America’s road infrastructure is inextricably linked to its powerful economic cycles and pioneering technological advancements. Since “about 1890,” the U.S. economy “has been the world’s largest,” consistently providing the financial capacity for ambitious infrastructure projects. This economic might has allowed for sustained investment in building and expanding the vast network of roads the nation relies upon.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed an “explosion of technological advancement” and “rapid economic expansion.” This era saw “tycoons led the nation’s expansion in the railroad, petroleum, and steel industries,” all of which are foundational to road construction and the vehicles that use them. Crucially, “the United States emerged as a pioneer of the automotive industry,” which transformed personal and commercial transportation, making roads a central component of economic and social life.

Economic downturns, while challenging, have also spurred significant infrastructure development. The “Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered the Great Depression,” but President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal plan of ‘reform, recovery and relief'” included “unprecedented and sweeping recovery programs and employment relief projects.” Many of these involved public works, including large-scale road construction, which not only provided jobs but also significantly upgraded and expanded the national road network, shaping its modern form.

Following World War II, “the U.S. emerged relatively unscathed from the war, with even greater economic power and international political influence.” This period of sustained “economic growth” allowed for continued investment in infrastructure, including the interstate highway system, further solidifying the nation’s reliance on road transportation. A thriving economy demands efficient logistics, and robust roads are central to facilitating the movement of goods and services that underpin economic prosperity.

The “1990s saw the longest recorded economic expansion in American history” and “advances in technology,” including innovations like the “World Wide Web” and microprocessors. While not directly roads, these technologies supported a dynamic economy that required efficient supply chains and transportation. Conversely, the “U.S. housing bubble culminated in 2007 with the Great Recession,” illustrating how economic instability can impact funding for infrastructure maintenance and new projects, highlighting the cyclical nature of investment.

Read more about: Navigating the Electric Shift: Why Key Car Brands Are Struggling in the EV Race and What it Means for Buyers

10. **The Enduring Legacy of Social and Political Policies on Roadway Equity and Conditions**Roadway development in the United States has been deeply influenced by historical social structures and political policies, often leading to varied conditions and access across different communities. During the colonial period, “enslavement of Africans was practiced in all the colonies by 1770,” primarily supplying “most of the labor for the Southern Colonies’ plantation economy.” This economic model likely dictated early road patterns in the South, prioritizing routes for agricultural transport over broader public access or equitable development.

Following the Civil War, the “Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution were ratified to protect civil rights,” aiming for “equal protection under the law for all persons” and prohibiting racial discrimination. However, this progress was severely undermined by subsequent “Supreme Court decisions, including Plessy v. Ferguson,” which “emptied the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of their force.” This allowed “Jim Crow laws in the South” and “segregation in communities across the country” to flourish, often reinforced by policies like “redlining.” These discriminatory practices influenced municipal planning and infrastructure investment, potentially leading to inferior road conditions and limited access in marginalized communities.

Federal policies designed to encourage settlement also left a significant imprint on road networks. The “Homestead Acts” (post-1865) “gave away free to some 1.6 million homesteaders” “nearly 10 percent of the total land area of the United States.” This rapid, decentralized settlement pattern in the American frontier necessitated the creation of countless local roads and pathways to connect isolated homesteads to larger towns and markets. These often rudimentary roads formed a dense, organic network that contrasted with more centrally planned urban or interstate routes.

The federal structure of government, with “Federalism grant[ing] substantial autonomy to the 50 states,” combined with local political dynamics, continues to shape road conditions. Decisions on infrastructure projects, maintenance schedules, and funding priorities are made at various levels, leading to a mosaic of road quality and safety standards. This decentralized approach can enable tailored solutions but also contribute to disparities depending on regional wealth, political will, and historical legacies.

Today, while the nation strives for a unified infrastructure, the shadows of past policies persist, affecting everything from road density to maintenance prioritization. Efforts by agencies like the EPA to address environmental issues, or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service enforcing the Endangered Species Act, demonstrate a modern evolution in governance. These entities ensure that current and future road development integrates broader societal values, moving towards a more sustainable and equitable transportation system, though the challenge of rectifying historical disparities remains.

As this comprehensive overview reveals, the conditions of America’s roads and intersections are a complex tapestry woven from geographical imperatives, historical turning points, shifting populations, economic realities, and layered governance structures. While the article’s scope precludes specific crash data, understanding these foundational influences is paramount. They highlight why achieving consistently safe and efficient road travel across such a diverse and dynamic nation remains an ongoing challenge, demanding adaptive strategies and continuous investment to navigate the legacies of the past and the demands of the future.