Have you ever wondered about the beating heart of Mindanao, a city that seamlessly blends natural splendor with urban dynamism? Welcome to Davao City, a place that’s much more than just a dot on the map. It’s a powerhouse, a melting pot, and a testament to resilience, consistently proving itself as one of the Philippines’ most significant and rapidly evolving urban centers.

From its staggering land area to its diverse population, Davao City stands out as a critical hub in the Davao Region and, indeed, the entire southern Philippines. It’s a city that carries the weight of history, shaped by centuries of indigenous life, colonial struggles, economic booms, and periods of social unrest. Yet, through it all, it has emerged stronger, always pushing the boundaries of what a Philippine city can be.

Join us as we embark on an exciting journey, peeling back the layers of this fascinating metropolis. In this first half of our deep dive, we’ll uncover the city’s fundamental identity, trace its ancient roots, witness the rise of an indigenous sultanate, navigate the complexities of its colonial past under both Spanish and American rule, and confront the devastating, yet formative, period of World War II. Get ready to discover the stories that built Davao City into the vibrant place it is today.

1. Davao City: A Metropolitan Powerhouse

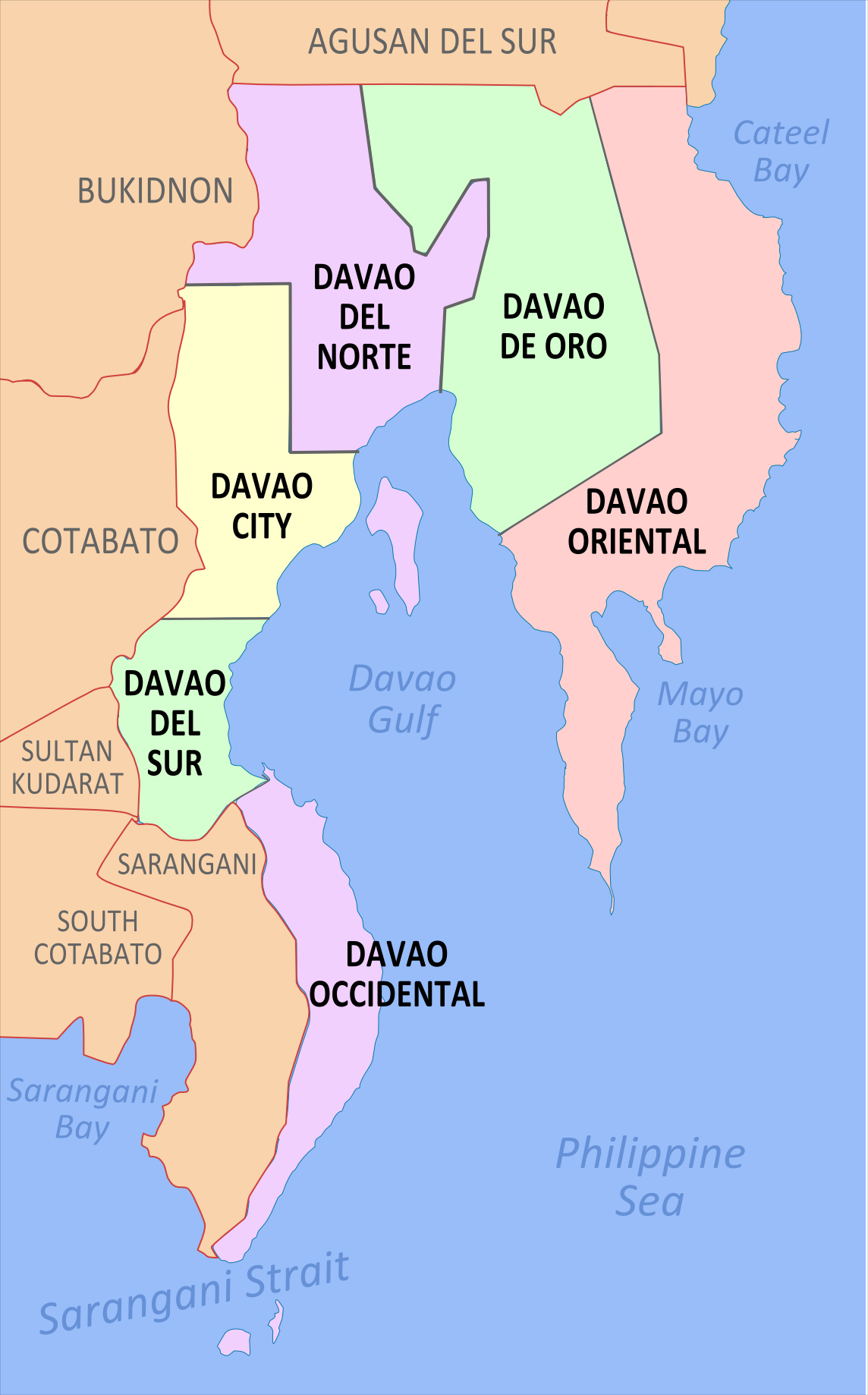

When you talk about significant urban centers in the Philippines, Davao City isn’t just on the list; it’s often near the top. Officially designated as a highly urbanized city within the Davao Region, it proudly holds the title of the largest city in the Philippines when measured by land area, sprawling across an impressive 2,443.61 square kilometers (943.48 sq mi). This vast expanse alone tells you a lot about its potential and scale.

But it’s not just about size. Davao City is also a demographic giant, securing its place as the third-most populous city in the Philippines, trailing only behind Quezon City and Manila. More significantly, it stands as the most populous city in the entirety of Mindanao, the Davao Region, and indeed, any city located outside of Metro Manila. Imagine the sheer vibrancy and diversity that such a large population brings to its streets and communities!

This isn’t just a collection of impressive statistics; it underscores Davao City’s undeniable influence. It serves as the undisputed regional center of the Davao Region and the bustling heart of Metro Davao, which is itself the second most populous metropolitan area in the Philippines. This central role isn’t just administrative; it extends deeply into the economic fabric of Mindanao, positioning Davao as the main trade, commerce, and industry hub for the entire island.

As you explore the city, you’ll quickly grasp its pivotal role. From its bustling markets and modern infrastructure to its strategic geographic location, Davao City truly embodies the essence of a major metropolitan powerhouse. It’s a place where opportunities converge, and the pulse of Mindanao’s economy beats strongest, setting trends and driving growth for the entire southern region.

2. The Echoes of Names: Unpacking Davao’s Etymological Roots

Ever wondered how a city gets its name? For Davao City, the story is rooted deep in the land and the languages of its indigenous peoples, specifically the Bagobo origins who have inhabited this fertile region for centuries. The name ‘Davao’ isn’t just a random label; it’s a phonetic blending, a linguistic echo of how three distinct Bagobo subgroups referred to the major waterway that gracefully empties into the Davao Gulf near the city.

The Obos, one of these fascinating subgroups who traditionally resided in the hinterlands, called the river ‘Davah’. This term was often pronounced with a gentle vowel ending, though later pronunciations adopted a harder ‘v’ or ‘b’ sound. But it wasn’t just a name for the river; for the Obos, ‘davah’ also carried the profound meaning of ‘a place beyond the high grounds’, beautifully alluding to the settlements nestled at the river’s mouth, embraced by the high, rolling hills that define the landscape.

Adding to this rich linguistic tapestry were the Clatta, also known as Giangan or Diangan, who referred to the river as ‘Dawaw’. And then there were the Tagabawas, another Bagobo subgroup, who simply called it ‘Dabo’. Imagine the diverse sounds and meanings converging, slowly blending over time to form the single, resonant name we know today. This etymological journey offers a powerful reminder of the city’s deep connection to its native heritage and the land itself.

It’s more than just a historical footnote; it’s a living testament to the ancestral voices that first breathed life into this region. The very name ‘Davao’ carries within it the stories and perspectives of the indigenous communities who were here long before any maps were drawn, offering a profound glimpse into their understanding and appreciation of this unique and significant place.

Product on Amazon: The Echoes: A Novel

Binding: Kindle Edition Product Group: Digital Ebook Purchas

Price: 14.99 USD

Rating: 4.0 Total reviews: 578

Shopping on Amazon >>

3. Precolonial & Maguindanao Eras: A Sultanate’s Rise on Davao Gulf

Long before any colonial flags were planted, the area now known as Davao City was a verdant, pristine wilderness, a lush forest that served as home to a rich tapestry of Lumadic peoples. Imagine groups like the Bagobos and Matigsalugs thriving here, alongside other vibrant ethnic communities such as the Aeta, Maguindanaon, and Kagan. This was a land untouched, where life revolved around the natural rhythms of the environment, particularly the powerful waterway the Bagobos, Maguindanaons, and Tausugs knew as the Tagloc River, near whose mouth a thriving settlement existed around what is now Bolton Riverside.

Curiously, in 1543, early Spanish explorers led by Ruy Lopez de Villalobos sailed past Mindanao, deliberately giving a wide berth to the area around the Davao Gulf, then known as the Gulf of Tagloc. Their cautious approach was due to a very real and significant threat: the formidable fleets of Moro warships that actively operated in the area. This strategic avoidance meant that for an astonishing three centuries, the Davao Gulf region remained virtually undisturbed by European explorers, preserving its indigenous character and allowing local powers to flourish unchecked.

This era of relative independence set the stage for the rise of a significant regional power. By the late 1700s, a Maguindanaon Datu named Datu Bago was rewarded the territory surrounding the Davao Gulf by the Sultan of Maguindanao Sultanate for his contributions in campaigns against the Spanish. Moving to the area around 1800, Datu Bago masterfully convinced the local Bagobos and other native groups to join his cause, successfully conquering and consolidating control over the entire Davao Gulf area. This was a strategic and powerful move, demonstrating remarkable leadership and foresight.

Having cemented his authority, Datu Bago established the formidable fortress of Pinagurasan in 1830, a site now occupied by the Bangkerohan Public Market, which served as his capital. From this strategic fortification and operational base, he rallied his forces, transforming Pinagurasan into a burgeoning settlement. It quickly grew into a small city, attracting Maguindanaons, Bagobos, and other nearby tribes, eventually becoming the main trade entrepot in the Davao Gulf area, a true testament to its burgeoning influence and prosperity.

By 1843, Datu Bago’s immense overlordship of the Davao Gulf was formally recognized, and he was crowned Sultan by his subjects at Pinagurasan. This crowning achievement effectively rendered his realm virtually independent from the Sultanate of Maguindanao, establishing it as a sovereign Sultanate on equal footing with the powerful Muslim kingdoms of Maguindanao and Sulu. This period represents a powerful chapter of indigenous self-governance and regional dominance, a vibrant era often overlooked in broader historical narratives.

4. Spanish Colonial Era: Conquest, Conflict, and a New Name

While the allure of the Philippine islands drew Spanish explorers as early as the 16th century, their influence in the Davao region remained remarkably negligible for centuries. It wasn’t until 1842 that the Spanish Governor-General Narciso Clavería issued a directive for the full-scale colonization of the Davao Gulf region, including the nascent area of what would become Davao City. This wasn’t just an arbitrary decision; it was born out of necessity, following the significant loss of Spanish colonies in the Americas during the 1820s and 1830s. The crown’s coffers were dwindling, and local officials in the Philippines were compelled to find new avenues for revenue, primarily through increased tribute from native populations, thus pushing for the conquest of Mindanao.

The thriving maritime trade in Davao Gulf made it an especially tempting target for Spanish military circles based in Manila. Their initial attempts to assert control began in 1842 with an incursion on the village of Sigaboy, where Spanish officials immediately demanded heavy tribute. The local natives, understandably distressed, appealed to Datu Bago for assistance. True to his protective role, Datu Bago responded swiftly, dispatching a combined naval and land force to decisively defeat and drive out the Spanish presence, a clear signal that this region would not be easily subdued.

For years, the Spanish dismissed Datu Bago as merely a ‘pirate and brigand,’ failing to take his numerous victories against them seriously. However, a turning point arrived in 1846 with the audacious burning of the Spanish trading vessel San Rufo and the massacre of its entire crew. This act, carried out by seaborne corsairs under Datu Bago’s direct orders, was particularly provocative, as the San Rufo had been carrying a letter of friendship from Sultan Iskandar Qudaratullah Muhammad Zamal al-Azam of Maguindanao to Governor-General Claveria. Incensed by this incident, the Spanish seized it as a crucial pretext to justify their conquest of the area, finally securing the consent of the Sultan of Maguindanao, who, perhaps strategically, disowned the Moros of Davao Gulf.

The official Spanish colonization of Davao Gulf thus began in earnest in April 1848. An expedition consisting of 70 men and women, led by José Cruz de Oyanguren of Vergara, Spain, landed on the estuary of the Davao River that same month. Their clear objective: conquer Pinagurasan, Datu Bago’s capital, and permanently end the menace posed by Moro raiders to Spanish vessels in the gulf. Oyanguren had ambitious orders from Manila to colonize the entire region, and in return, he sought the governorship of the conquered territory and a ten-year monopoly on its commerce.

At this crucial juncture, Oyanguren found an unexpected ally in Datu Daupan, a Mandaya chieftain who ruled Samal Island and was an archrival of Datu Bago. Seizing this strategic opportunity, Cruz de Oyanguren forged an alliance between Spain and the Mandayas of Samal Island. They assaulted Pinagurasan, but the Bagobo natives mounted fierce resistance, causing Oyanguren’s Samal Mandaya allies to desert. A grueling three-month-long battle ensued, only decided by the timely arrival of an infantry company, which sailed in warships from Zamboanga as reinforcements. This ultimately ensured the Spanish takeover of the settlement, forcing the defeated Bagobos, including Datu Bago, to flee further inland to Hijo, where the formidable Datu would eventually pass away two years later.

Following his victory over Datu Bago and the conquest of Pinagurasan, Cruz de Oyanguren established the town of Nueva Vergara on June 29, 1848, in the mangrove swamps of what is now Bolton Riverside. This new town, named in honor of his hometown in Spain, incorporated Pinagurasan and saw Oyanguren become its first governor. Just shy of two years later, on February 29, 1850, the province of Nueva Guipúzcoa was established via royal decree, with Nueva Vergara as its capital, again reflecting Oyanguren’s homeland. However, his economic plans for the region faltered, leading to his eventual replacement. The province itself was dissolved on July 30, 1860, becoming the Politico-Military Commandery of Davao. By 1867, responding to the strong clamor of its natives, the Spanish government officially accepted a petition to rename Nueva Vergara to ‘Davao’, embracing the name the indigenous peoples had used since its very inception. Despite these administrative changes, Spanish control remained unstable, constantly challenged by Lumad and Moro natives who fiercely resisted attempts at forced resettlement and conversion to Christianity.

5. The American Period Boom: Plantation Economy and Charter City Status

As the curtain fell on the Philippine Revolution and the Spanish authorities departed Davao in 1898, a brief period of Filipino revolutionary control emerged. Locals like Pedro Layog and Jose M. Lerma represented the town at the Malolos Congress, signifying Davao’s inclusion in the nascent First Philippine Republic. However, this period was short-lived. When American forces landed in Davao later the same year, they encountered no recorded resistance, paving the way for a new era that would profoundly transform the town.

The dawn of American administration in 1900 brought with it a surge of economic opportunities that forever altered Davao’s landscape. Massive swathes of its pristine areas, primarily lush forests and incredibly fertile grasslands, were declared open for agricultural investment. This policy served as a powerful magnet, attracting a wave of foreign businessmen, with Japanese entrepreneurs leading the charge. These visionary investors quickly settled in the region, staking their claims on Davao’s vast lands and meticulously transforming them into sprawling, highly productive coconut and banana plantations.

In what felt like an instant, Davao underwent a dramatic metamorphosis. From a small, sparsely inhabited town, it rapidly evolved into a bustling economic center, serving as a vital nexus for the entire Davao Gulf region. Its population swelled dramatically, no longer just composed of native peoples but now heavily populated by tens of thousands of settlers and economic migrants drawn from Luzon, Visayas, and a substantial number from Japan. To facilitate the burgeoning international export of Davao’s rich agricultural products, the Port of Davao was officially established and opened in the very same year, symbolizing the town’s newfound global connectivity.

Administratively, Davao saw several changes that reflected its growing importance. From 1903 to 1914, it was incorporated as part of Moro Province. Upon the dissolution of this province in 1914, Davao was elevated to the status of a provincial capital with the establishment of Davao Province. The city’s Legislative Council Building, built in 1926, served as the provincial capitol, the same year the Davao Municipal Hall—which would later become the City Hall—was constructed, laying down the architectural foundations of its administrative core.

The town’s rapid and undeniable progress became impossible to ignore. On March 16, 1936, Congressman Romualdo Quimpo from Davao introduced Bill 609, which was subsequently passed as Commonwealth Act 51. This landmark legislation officially created the City of Davao, encompassing the former town of Davao and the municipal district of Guianga. The bill also stipulated the appointment of local officials by the president. By this time, the newly designated city was already largely populated by Japanese businessmen and settlers, who had become integral parts of its local fabric. Davao was inaugurated as a charter city by President Manuel L. Quezon on October 16, 1936, with its charter officially taking effect on March 1, 1937, marking it as one of the very first two towns in Mindanao to achieve city status, alongside Zamboanga, a true testament to its burgeoning significance.

6. World War II’s Dark Chapter: Occupation, Atrocities, and Liberation

The year 1941 cast a long, dark shadow over the burgeoning progress of Davao City. On December 8, 1941, just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese planes unleashed a devastating bombing raid on Davao’s bustling harbor, marking the city as an early target in World War II. Barely two weeks later, from December 20, Japanese forces made landfall and began an occupation that would brutally define the city’s experience until 1945. Davao was among the earliest Philippine cities to fall, and it was quickly transformed into a fortified bastion of Japanese defense, a strategic stronghold in their Pacific campaign.

Under the oppressive and brutal Japanese regime, the city experienced unspeakable horrors. A particularly grim aspect of this occupation was the abhorrent “comfort women” system. Girls, teenagers, and young adults from Davao were kidnapped by Japanese soldiers and systematically forced into sexual slavery. These victims endured routine gang-rapes and, tragically, many were killed. The barbarity extended beyond Filipino nationals, with Korean and Taiwanese individuals also forcibly brought to Davao and subjected to the same horrific conditions as sex slaves. This dark period remains a painful and indelible scar on the city’s history, a stark reminder of the profound human cost of war.

As the tide of the war began to turn, Davao found itself caught in another maelstrom of destruction. Before American forces finally landed in Leyte in October 1944, the city was subjected to extensive bombing campaigns led by General Douglas MacArthur. These aerial assaults, aimed at weakening Japanese defenses, devastated much of the urban landscape, tearing through infrastructure and civilian areas alike. The city became a battleground, scarred by the relentless conflict.

The Battle of Davao, which unfolded towards the very end of World War II during the Philippine Liberation, was one of the longest and bloodiest engagements in the entire campaign. The ferocious fighting brought tremendous destruction to the city, undoing much of the economic and physical strides that Davao had made in the prosperous decades leading up to the Japanese occupation. Buildings were reduced to rubble, livelihoods were shattered, and the vibrant economic hub was left in ruins, facing the monumental task of rebuilding from the ashes of war.”

7. Postwar Rebirth and the Road to Regional Leadership

As the dust settled after the devastating conflict of World War II, Davao City, with its characteristic resilience, embarked on a remarkable journey of recovery. By 1945, with the war finally over, the city quickly regained its crucial status as Mindanao’s agricultural and economic hub. This wasn’t just a recovery; it was a reinvention, seeing a surge in diverse exports. Beyond its traditional produce, wood products like plywood and timber, along with new varieties of agricultural goods such as copra and a wider range of bananas, became readily available for international trade, signaling a robust economic rebound.

The immediate postwar period also brought significant social shifts. While a substantial portion of the city’s Japanese locals, who had made up 80% of Davao’s population before the war, assimilated into the Filipino population, the raw enmity of recent conflict also led to others being expelled from the country. Despite these changes, the period stretching through the 1950s and into the mid-1960s was largely characterized by peace and progressive growth for Davao. Ethnic tensions were minimal during this time, and the troubling presence of secessionist groups, which would later emerge, was virtually non-existent, painting a picture of harmonious development.

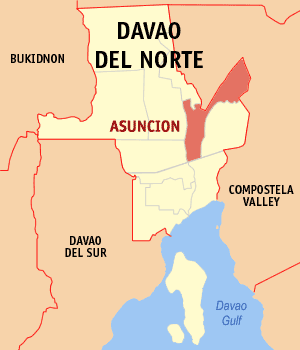

This era of growth also brought about significant administrative restructuring. In 1967, the Province of Davao underwent a major division, splitting into three distinct provinces: Davao del Norte, Davao Oriental, and Davao del Sur. With this reorganization, Davao City, while still a crucial urban center, became geographically situated under Davao del Sur. However, it was no longer the provincial capital, instead solidifying its role as the undisputed commercial heart of southern Mindanao. This pivotal year also marked a significant milestone for local governance with the first-ever election of an indigenous person, Elias Lopez, a full-blooded Bagobo, to the esteemed office of Mayor of Davao City, underscoring the city’s evolving political landscape.

8. Navigating Tumultuous Times: Social Unrest and the 1980s

The relative peace and progress of Davao City began to fray in the late 1960s, mirroring the wider national unrest brewing during President Ferdinand Marcos’s first term. A critical turning point arrived with the news of the Jabidah massacre, an incident that ignited a firestorm of furor within the Moro community. This tragic event not only fueled existing ethnic tensions but also tragically encouraged the formation of powerful secessionist movements across Mindanao. Compounding these social fractures, an economic crisis struck in late 1969, leading to widespread social unrest and protests. The government’s violent crackdowns on these demonstrations, unfortunately, had the unintended consequence of radicalizing many students nationwide, setting the stage for future conflicts.

When Martial Law was declared in 1972, avenues for expressing grievances against government abuses effectively vanished. This drastic measure drove many disaffected students to join the New People’s Army (NPA), bringing the Communist rebellion to Davao and the rest of Mindanao for the very first time. The movement continued to gain momentum throughout the following decade, although it faced struggles by the early 1980s. This period saw prominent party thinker and ideologue Edgar Jopson relocate to Davao, where he was tragically killed during a raid in Skyline Subdivision in September 1982, a significant loss for the insurgency.

Yet, paradoxically, the years immediately following Jopson’s death witnessed an unmanageable surge in the Communist Party’s ranks. This growth coincided with the severe 1983 Philippine economic nosedive and the shocking assassination of Ninoy Aquino just months later, events that saw the New People’s Army expand to seven battalion-sized fronts. Emboldened, the NPA began experimenting with aggressive strategies like urban insurrectionism. The mid-1980s became a period of intense violence, initially marked by assassinations of corrupt officials and policemen, but escalating dramatically between mid-1984 and August 1985 with the killing of 16 journalists—a stark increase from the six killed in the entire decade prior. Agdao, a poor barangay that provided significant support to the NPA, earned the grim moniker “Nicaragdao,” while foreign press began labeling Davao as the Philippines’ “Murder Capital” and “Killing Fields,” further solidifying Mindanao’s reputation as “the laboratory of the revolution” due to these audacious urban tactics.

In 1984, a new and troubling force emerged: right-wing vigilantes. With the support of Lt. Colonel Franco Calida, commander of the Philippine Constabulary Davao City Metropolitan Command, the armed group “Alsa Masa” (People’s Rise) was formed specifically to counter the growing NPA presence. Their emergence, alongside internal infighting within the NPA triggered by a hunt for deep penetration agents, was perceived by some as reducing the insurgent presence in Davao. However, this came at a grave cost, as the Alsa Masa itself became notorious for committing severe human rights violations, adding another layer of complexity and suffering to the city’s volatile landscape.

Amidst this escalating violence, most Davao residents remained staunchly against extremism from either side. Early examples of this peaceful opposition included Archbishop Antonio L. Mabutas, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Davao, who bravely became one of the first religious leaders to peacefully speak out against the egregious human rights abuses of the Marcos dictatorship. However, these peaceful citizens often lacked the necessary political clout to significantly influence the dire situation before 1983. A notable stabilizing element arrived with the designation of then-Colonel Rodolfo Biazon as commander of the 3rd Marine Brigade assigned to Davao. In what the international press lauded as “the most sophisticated approach” to addressing the insurgency, Biazon consciously eschewed the aggressive stance preferred by the Philippine Constabulary. Instead, he prioritized outreach and community engagement, actively visiting schools and communities, and reassuring the public that any Marine involved in abuses would be disciplined.

Ordinary citizens began to find a stronger voice for change after a series of seminal events: the economic crisis of 1983, the assassination of Ninoy Aquino, and the tragic murder of prominent Davao City journalist Alex Orcullo at a checkpoint in Barangay Tigatto on October 19, 1984. These incidents galvanized city figures like Soledad Duterte, who courageously organized a protest group called the “Yellow Friday Movement.” This movement steadily gained support, eventually playing a vital role leading up to 1986, when Marcos was finally ousted and forced into exile. It’s also important to acknowledge the numerous Davaoeños from various sectors of society who are honored at the Philippines’ Bantayog ng mga Bayani, a national memorial that recognizes martyrs and heroes who valiantly fought for democracy against the authoritarian regime, including individuals like Fernando ‘Nanding’ Esperon, Atty Laurente ‘Larry’ Ilagan, Eduardo Lanzona, Maria Socorro Par, Evella Bontia, Nicolas Solana Jr., Ricky Filio, and Joel Jose, whose sacrifices are remembered for their fight against oppression.

9. A New Dawn: Post-People Power and the Duterte Era

The monumental success of the People Power Revolution in 1986 ushered in a new era for the Philippines, and Davao City was no exception. Given that many of the local leaders at the time had been closely associated with the Marcos regime, the revolutionary government that took power after Marcos’s ouster promptly removed them from their positions. This political realignment created an opening for new leadership to emerge, reflecting the people’s renewed hope for democratic governance and systemic change.

In a significant move, President Corazon Aquino, leading the nascent post-revolutionary government, appointed Rodrigo Duterte, the son of the respected activist Soledad Duterte, as the temporary Vice Mayor of Davao City. This appointment marked the beginning of a transformative period in Davao’s political landscape. Rodrigo Duterte later successfully ran for Mayor of Davao City, securing the top city office for multiple terms from 1988 to 1998, again from 2001 to 2010, and once more from 2013 to 2016. His long and impactful tenure as mayor ultimately served as a springboard for his historic ascent to the presidency of the Philippines, cementing his profound and lasting influence on both Davao City and the nation.

10. Davao’s Geographical Grandeur: From Lofty Peaks to Lush Lowlands

Davao City’s geographical setting is nothing short of spectacular, defining much of its character and charm. Strategically located in southeastern Mindanao, it gracefully hugs the northwestern shore of the expansive Davao Gulf, directly across from the picturesque Samal Island. This prime location places it approximately 946 kilometers (588 mi) southeast of Manila by land, and 971 kilometers (524 nmi) by sea, highlighting its significant distance from the national capital but also its critical position within the southern Philippines. The city’s landscape is further dramatically framed by the majestic silhouettes of Mount Apo and Mount Talomo, both prominently visible from many vantage points, adding to its natural allure.

Sprawling across a total land area of about 2,443.61 square kilometers (943.48 sq mi), Davao City’s topography is wonderfully varied. The western sections, particularly the Marilog district, are distinctly hilly, offering elevated views and cooler climes. From these heights, the land gently slopes down towards the fertile southeastern shore, creating a diverse environment suitable for both agriculture and urban development. Dominating the city’s southwestern tip is Mount Apo, the undisputed highest peak in the Philippines. Recognizing its ecological significance, Mount Apo National Park, encompassing the mountain and its surrounding vicinity, was inaugurated by President Manuel L. Quezon in 1936 through Proclamation 59, a vital step to protect its unique flora and fauna.

The lifeblood of the city’s drainage system is the Davao River, its primary channel. This impressive 160-kilometer (99 mi) river originates in the town of San Fernando, Bukidnon, and drains a vast area of over 1,700 square kilometers (660 sq mi). Its journey culminates at its mouth, located in Barangay Bucana within the Talomo District, where it gracefully empties into the Davao Gulf. This crucial waterway not only shapes the landscape but also supports local ecosystems and communities along its banks.

Davao enjoys a tropical rainforest climate, classified as Af under the Köppen system, meaning it experiences very little seasonal variation in temperature, making it a truly year-round tropical paradise. The Intertropical Convergence Zone largely dictates its weather patterns, leading to consistently warm conditions, with average monthly temperatures always exceeding 26 °C (78.8 °F). Although the city experiences significant rainfall year-round, notably in winter, the largest amounts occur during the summer months. Interestingly, it is considered subequatorial rather than purely equatorial due to its rare encounter with cyclones. Despite its location within the Asian portion of the Pacific Ring of Fire, Davao City has historically suffered few earthquakes, with most being minor, and the towering Mount Apo, 40 kilometers southwest of the city proper, remains a dormant volcano, contributing to the city’s relative geological stability.

This vibrant region is also a treasure trove of biodiversity. Mount Apo is a vital sanctuary for numerous bird species, with a remarkable 111 of them endemic to the area. It proudly serves as a critical habitat for one of the world’s largest and most magnificent raptors, the critically endangered Philippine eagle, which is also the country’s national bird. The Philippine Eagle Foundation, dedicated to conserving this iconic species, is fittingly based near the city. Beyond its avian wonders, Davao is famed for its rich plant life, including the exquisite waling-waling orchid, often called the ‘Queen of Philippine Flowers’ and one of the country’s national flowers, which is endemic to the region. The fertile lands around Mount Apo also yield an abundance of delectable fruits like the mangosteen, revered as the ‘queen of fruits,’ and the iconic durian, famously known as the ‘king of fruits,’ further solidifying Davao’s reputation as a horticultural haven.

11. A Tapestry of People and Tongues: Davao’s Vibrant Demographics

Davao City is a dynamic melting pot of cultures and people, boasting a vibrant demographic landscape that truly reflects its role as a major urban center. As of the 2020 census, the city’s population stands at an impressive 1,776,949 people. When considering Metro Davao, with the city at its core, the population reached approximately 2.77 million inhabitants in 2015, making it the third-most-populous metropolitan area in the Philippines and the most populous city in Mindanao. A significant milestone was achieved in the 1995 census when Davao City’s population surpassed one million inhabitants, becoming the first city outside Metro Manila and the fourth nationwide to do so. This rapid population increase throughout the 20th century, and continuing into the present day, has been largely driven by massive waves of immigration from various parts of the nation.

Residents of Davao City and the broader Davao Region are affectionately known as Davaoeños, a term that encompasses a rich array of ethnicities. The vast majority of local Davaoeños are descended from migrant settlers, predominantly Visayans from recent centuries and decades, with Cebuanos forming the largest group, complemented by Ilonggos (Hiligaynon speakers) and their respective mestizo descendants. The indigenous peoples, collectively categorized as Lumads, constitute a significant and vital part of the remaining local population, maintaining their unique cultural heritage. Furthermore, the city is home to numerous other non-Visayan ethnic groups, including Tagalogs, Kapampangans, and Ilocanos, who are also descendants of migrant settlers from Luzon, particularly from Metro Manila, Central Luzon, Calabarzon, the Ilocos Region, the Cordillera Administrative Region, and Cagayan Valley, adding to the city’s incredible diversity.

The city also boasts a strong presence of Moro ethnic groups, including the Maguindanaons, Maranaos, Iranuns, Tausugs, and Sama-Bajaus, each contributing to the rich cultural tapestry. Historically and in more recent times, Chinese Filipinos and Japanese Filipinos from various parts of the Philippines have established sizable and influential communities in Davao. In recent decades, a new wave of modern migrants has arrived, including Indonesians, Malaysians, Chinese (from both China and Taiwan), Japanese, and Koreans, forming smaller but growing communities within Davao City. Even non-Asian foreigners, such as Americans and Europeans, are present in small numbers, further emphasizing Davao’s global appeal and diverse population.

When it comes to communication, Cebuano reigns as the most widely spoken language in Davao City and its surrounding satellite towns, a testament to the strong Visayan migration. Filipino (Tagalog) closely follows as the second most spoken casual language, reflecting its national prominence. English serves as the formal medium of instruction in schools and is widely understood by residents, frequently used in various professional fields. Beyond these dominant languages, a vibrant array of indigenous tongues such as Giangan, Kalagan, Tagabawa, Matigsalug, Ata Manobo, and Obo are spoken, preserving the heritage of the native communities. Chavacano Davaoeño and Hiligaynon are also spoken by minorities, while Maguindanao, Maranao, Sama–Bajaw, Iranun, Tausug, Ilocano, and Kapampangan can also be heard. Furthermore, Philippine Hokkien and Japanese are privately spoken among Chinese Filipinos and Japanese Filipinos, respectively, with Mandarin (Standard Chinese) and Japanese also taught in respective community schools. A fascinating linguistic phenomenon has also developed, where locals significantly mix Tagalog terms and grammar into their Cebuano Bisaya speech, largely due to older generations speaking Tagalog to their children, the influence of migrant settlers from Luzon, and the prevalence of Filipino (Tagalog) in modern mass media and school curricula, making Tagalog a secondary casual lingua franca.

Davao City’s spiritual landscape is as diverse as its population. The overwhelming majority of its inhabitants are Roman Catholic Christians, constituting 78% of the population, a reflection of the Philippines’ strong Catholic heritage. Islam forms the next largest religious affiliation at 4%, representing a significant and established community within the city. Other Christian groups, including the Iglesia ni Cristo, Jesus Miracle Crusade, Pentecostal Missionary Church of Christ (4th Watch), and the Restorationist Church Kingdom of Jesus Christ, collectively account for eighteen percent of the city’s religious background, adding to its spiritual mosaic. The Seventh-day Adventist Church, the United Church of Christ in the Philippines, the Philippine Independent Church, and the Baptists represent other notable Christian denominations. Beyond these, a smaller presence of other faiths such as Sikhism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, animism, and irreligion also exist, demonstrating the city’s openness to various beliefs.

It’s noteworthy that the Restorationist Church Kingdom of Jesus Christ had its origins right here in Davao City, led by Apollo Quiboloy, who claims to be the “Appointed Son of God.” The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Davao serves as the main metropolitan see of the Roman Catholic Church in southern Mindanao, overseeing the city of Davao, the Island Garden City of Samal, and the municipality of Talaingod in Davao del Norte province. Under its jurisdiction are three suffragan dioceses: Digos, Tagum, and Mati, which are the capital cities of the three Davao provinces. Archbishop Romulo Valles, appointed by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012, took office at San Pedro Cathedral on May 22, 2012. Saint Peter, locally revered as San Pedro, holds the honor of being the city’s patron saint, reflecting a deeply rooted spiritual tradition.

12. The Economic Engine of Mindanao: Powering Growth and Prosperity

Davao City isn’t just a picturesque urban center; it’s a formidable economic powerhouse, widely recognized as the largest city economy in Mindanao and the leading local economy in the southern Philippines. Its strategic position makes it an integral part of the East Asian Growth Area, a crucial regional economic-cooperation initiative in Southeast Asia. This strong economic foundation is further underscored by a projected average annual growth of 2.53 percent over a 15-year period, a remarkable statistic that saw Davao as the only Philippine city to break into the top 100 in this significant economic assessment.

Agriculture remains the bedrock of Davao’s economy, standing as its largest economic sector. The city is celebrated as the island’s leading exporter of a rich variety of fruits, including succulent mangoes, tangy pomeloes, prized bananas, versatile coconut products, sweet pineapples, tender papayas, exotic mangosteens, and high-quality cacao. The iconic durian, locally grown and harvested in abundance, is also a notable export, though bananas continue to hold the top spot as the city’s largest fruit export. The burgeoning chocolate industry represents a thrilling new development, with Malagos Chocolate, developed by Malagos Agriventures Corp., now recognized globally as the country’s leading artisan chocolate. Meanwhile, Seed Core Enterprises proudly stands as the Philippines’ biggest exporter of cacao to the international giant Barry Callebaut, highlighting Davao’s growing influence in the global cocoa market.

The agricultural landscape is bolstered by the significant operations and headquarters of prominent local corporations such as the Lorenzo Group, Anflo Group, AMS Group, Sarangani Agricultural Corp., and Vizcaya Plantations Inc., all contributing to the region’s prosperity. Furthermore, multinational giants like Dole, Sumifru/Sumitomo, and Del Monte have strategically established their regional headquarters here, leveraging Davao’s fertile lands and robust agricultural infrastructure. Beyond the farms, the bountiful Davao Gulf provides a vital livelihood for countless fishermen, yielding a diverse catch that includes valuable yellowfin tuna, brackish water milkfish, mudfish, shrimp, and crab. Most of these fresh catches are meticulously discharged at the bustling fishing port in Barangay Toril, from where they are distributed and sold in the city’s numerous vibrant markets.

Davao City’s industrial sector is equally robust, contributing significantly to its reputation as Mindanao’s main trade, commerce, and industry hub, and indeed, one of the island’s key financial centers. Phoenix Petroleum, a multinational oil company, proudly calls Davao City home, notably being the first company in the Philippines based outside Metro Manila to be included in the prestigious PSE Composite Index. The city also hosts several major industrial plants, including those of Coca-Cola Bottlers, Phil., Pepsi-Cola Products, Phil., Interbev Phil Inc., and RC Cola Phil., all vital to the beverage industry. Additionally, a substantial number of fruit packaging-exporting facilities and food manufacturing plants thrive here. The city is also a hub for industrial construction, featuring operations from Holcim Philippines, Union Galvasteel Corporation, and SteelAsia. The SteelAsia plant, completed in December 2014, is particularly notable as the largest and most modern steel rolling mill production facility in the country, purposely built to enhance national steel production and drive down construction costs across Mindanao.

The commercial heart of Davao City beats strong, evidenced by the presence of key financial institutions. BDO Network Bank (formerly One Network Bank) is based here and holds the distinction of being the largest rural bank in the Philippines in terms of assets, with most of its branches strategically located in Mindanao, including 17 areas where it stands as the sole financial-services provider. Government social-insurance agencies, such as the Social Security System (SSS) and Government Service Insurance System (GSIS), also maintain important locations in the city, providing essential services to the populace. Davao’s urban sprawl encompasses several vibrant commercial areas, including the bustling downtown area (also known as the city center), the dynamic Davao Chinatown (Uyanguren), Bajada, Lanang, Matina, Ecoland, Agdao, Buhangin, Tibungco, Toril, Mintal, and Calinan, with the latter three situated in the southwestern part of the city.

For those seeking retail therapy, Davao City is dotted with an impressive array of shopping centers. Among the most notable is Gaisano Mall of Davao, which first opened its doors in April 1997 and proudly stands as the largest Gaisano Mall in the Philippines. Abreeza, which debuted on May 12, 2011, holds the distinction of being the first and largest Ayala Mall in Mindanao, offering a premium shopping experience. SM Lanang Premier is another highlight, being the first SM Premier Mall in Mindanao and the second SM Mall within the city, further cementing its retail dominance. Other major malls include the NCCC Mall of Davao (currently under reconstruction since 2021 following its 2017 fire) and SM City Ecoland, which was the very first SM Mall in both the city and Mindanao. History buffs will appreciate NCCC Mall VP (formerly Victoria Plaza Mall), located on J.P. Laurel Ave., which holds the title of the oldest shopping mall in the city, established back in 1992. The modern Felcris Centrale, a mixed-use development, further adds to the city’s diverse commercial offerings, ensuring Davao City remains a buzzing hub of trade, commerce, and industry.

And there you have it, a comprehensive journey through Davao City, a place that truly embodies the spirit of the Philippines. From its ancient rivers and resilient people to its soaring mountains and bustling economic centers, Davao continues to write its story as a beacon of growth, culture, and opportunity in Mindanao. It’s a city that invites you to explore, to discover, and to fall in love with its unique blend of tradition and modernity, constantly proving why it’s a cornerstone of the nation. Truly, Davao City isn’t just a destination; it’s an experience, a vibrant pulse in the heart of the South, always evolving, always welcoming.