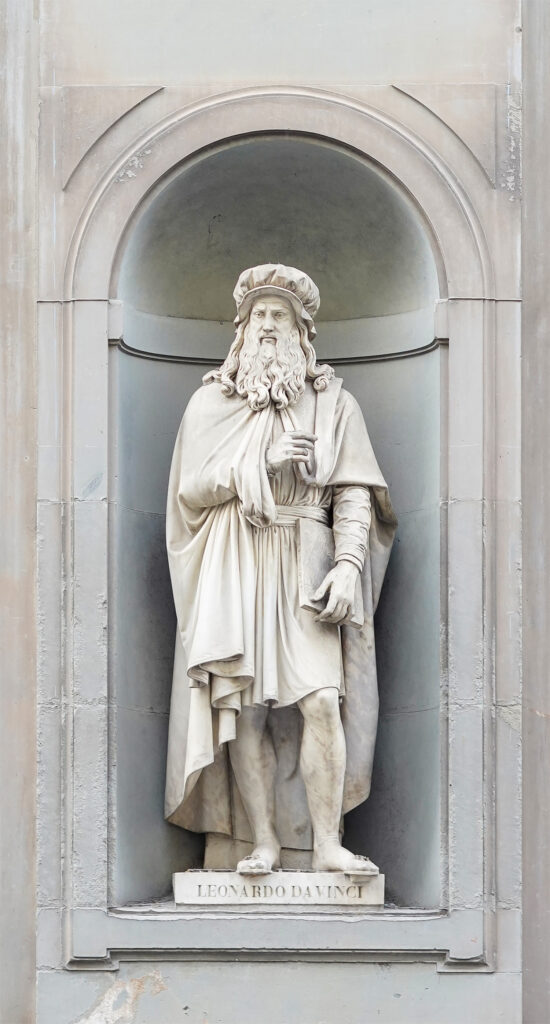

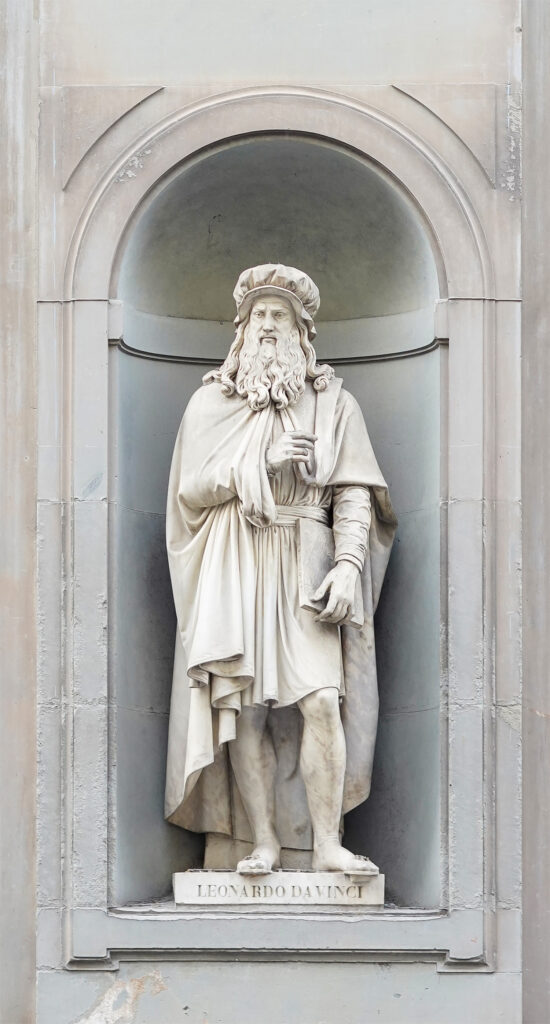

When we speak of a true genius, a name that invariably rises to the forefront is Leonardo da Vinci. An Italian polymath of the High Renaissance, Leonardo was not merely a painter, but also a draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. His fame initially rested on his achievements as a painter, but his notebooks, filled with drawings and notes on everything from anatomy to astronomy, reveal a mind that epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal, leaving a contribution to later generations of artists matched only by his contemporary, Michelangelo.

What makes Leonardo’s story so captivating is the sheer breadth of his curiosity and his relentless pursuit of knowledge, a trait that makes him relatable even today. He was a man who saw no boundaries between art and science, and whose diverse interests continually incited admiration, making him a frequent namesake and subject in culture. His life was a vibrant tapestry woven with artistic triumphs, scientific breakthroughs, personal challenges, and fascinating encounters with the most powerful figures of his time.

Join us as we embark on a journey through the remarkable life of Leonardo da Vinci, exploring the pivotal moments, the groundbreaking projects, and the personal touches that shaped this extraordinary individual. From his humble beginnings to his final days in a foreign land, we uncover the fascinating trajectory of a man whose collective works continue to inspire awe and wonder, proving why he remains one of history’s most beloved and studied figures.

1. **Leonardo’s Genesis: Birth and Early Life (1452–1472)**

Our story begins on April 15, 1452, in, or close to, the Tuscan hill town of Vinci, Italy, a mere 20 miles from Florence. Leonardo da Vinci, properly named Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, which translates to “Leonardo, son of ser Piero from Vinci,” was born out of wedlock to Piero da Vinci, a Florentine legal notary, and Caterina di Meo Lippi, a woman from the lower class. This humble beginning, outside the traditional societal norms of the time, set the stage for a life that would continually defy convention.

There’s a touch of mystery even about his exact birthplace; while a local oral tradition, recorded by historian Emanuele Repetti, suggests he was born in Anchiano, a quiet country hamlet offering privacy for an illegitimate birth, it’s also possible he was born in a house Ser Piero almost certainly had in Florence. Both of Leonardo’s parents married separately the year after his birth. Caterina, who later appears in Leonardo’s notes simply as “Caterina” or “Catelina,” is generally identified as Caterina Buti del Vacca, who married a local artisan.

Ser Piero, after being betrothed to Caterina, married Albiera Amadori, and after her death, went on to have three subsequent marriages. From these unions, Leonardo eventually had a staggering 16 half-siblings, though only 11 survived infancy. These siblings were much younger than he was, with the last being born when Leonardo was 46 years old, and he reportedly had very little contact with them, painting a picture of a somewhat isolated familial existence for the young polymath.

Very little is truly known about Leonardo’s childhood, much of it shrouded in myth, partly due to the frequently apocryphal *Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects* by 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari. Tax records indicate that by at least 1457, he resided in the household of his paternal grandfather, Antonio da Vinci, though he might have spent earlier years with his mother. Despite his father’s successful career as a descendant of a long line of notaries, Leonardo received only a basic and informal education in vernacular writing, reading, and mathematics, possibly because his artistic talents were recognized early, leading his family to focus their attention there. This early recognition set him on a path destined for greatness.

Later in life, Leonardo recorded what he believed to be his earliest memory in the Codex Atlanticus. While writing on the flight of birds, he recalled an incident from infancy where a kite came to his cradle and opened his mouth with its tail. Commentators still debate whether this intriguing anecdote was an actual memory or a fantastical creation, adding another layer of enigma to his fascinating early life.

2. **The Apprentice Years: Verrocchio’s Workshop**

In the mid-1460s, a crucial turning point occurred when Leonardo’s family relocated to Florence, a city pulsating with Christian Humanist thought and culture. Around the age of 14, young Leonardo began his formal artistic journey as a *garzone*, or studio boy, in the bustling workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio. Verrocchio was not just any artist; he was the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his time, and this period coincided with the death of his own master, the renowned sculptor Donatello. Leonardo’s path was clearly set among the titans of the Renaissance.

By the age of 17, Leonardo became a full apprentice, a rigorous training period that lasted an impressive seven years. This workshop was a vibrant hub, where other future luminaries like Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli, and Lorenzo di Credi also apprenticed or associated. It was here that Leonardo was immersed in an astonishing array of theoretical and technical skills, far beyond mere painting. He learned drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics, and woodwork, alongside the fundamental artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modeling.

Florence at this time was a melting pot of artistic innovation. Leonardo was a contemporary of Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Perugino, all slightly older, whom he would have encountered at Verrocchio’s studio or at the Platonic Academy of the Medici. The city itself was adorned with groundbreaking works by artists such as Masaccio, whose frescoes were celebrated for their realism and emotion, and Ghiberti, whose “Gates of Paradise” dazzled with gold leaf and complex compositions. Piero della Francesca had delved into the scientific study of perspective and light, and Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise *De pictura* profoundly influenced younger artists, including Leonardo, shaping his observations and artworks.

Much of the painting within Verrocchio’s workshop was, by common practice, executed by his assistants. It is famously recounted by Vasari that Leonardo collaborated with Verrocchio on his *The Baptism of Christ* (c. 1472–1475). Leonardo painted the young angel holding Jesus’s robe with such exceptional skill, purportedly superior to his master’s, that Verrocchio allegedly put down his brush and never painted again – a claim that, while likely apocryphal, underscores Leonardo’s burgeoning talent. His hand is also indicated in the application of the new technique of oil paint to areas of the mostly tempera work, including the landscape, rocks, and much of Jesus’s figure. It is even suggested that Leonardo may have served as a model for two of Verrocchio’s works: the bronze statue of David and the archangel Raphael in *Tobias and the Angel*.

Another captivating story from Vasari describes Leonardo as a very young man receiving a commission from a local peasant to paint a round buckler shield. Inspired by the myth of Medusa, Leonardo responded with a painting of a fire-spitting monster so terrifying that his father, Ser Piero, bought a different shield for the peasant. He then sold Leonardo’s masterpiece to a Florentine art dealer for 100 ducats, who, in turn, sold it to the Duke of Milan. This early anecdote perfectly illustrates Leonardo’s profound imaginative power and the immediate, powerful impact of his artistic vision.

Read more about: A Journey Through Genius: Unveiling the Life, Art, and Enduring Legacy of Leonardo da Vinci

3. **Emerging Master: The First Florentine Period (1472 – c. 1482)**

By 1472, at the age of 20, Leonardo had achieved a significant milestone: he qualified as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke, the esteemed guild for artists and doctors of medicine. Yet, despite his father setting him up in his own workshop, his deep attachment to Verrocchio meant he continued to collaborate and live with his former master. This period marked his transition from apprentice to an independent artist, a time of both new freedoms and ongoing mentorship. His earliest known dated work, a 1473 pen-and-ink drawing of the Arno valley, showcases his meticulous observation skills even at this nascent stage.

During this time, Leonardo’s inventive mind was already at work on practical applications. According to Vasari, it was the young Leonardo who first put forth the ambitious suggestion of making the Arno river a navigable channel between Florence and Pisa. This demonstrates his early interest in engineering and his desire to apply his intellect to solve real-world problems, a trait that would define his entire career.

January 1478 brought a significant validation of his growing reputation: Leonardo received an independent commission to paint an altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in the Florentine town hall, the Palazzo della Signoria. This commission was a clear indication of his independence from Verrocchio’s studio, solidifying his status as a sought-after master. It was a testament to the fact that Florence recognized his unique talent and entrusted him with significant artistic undertakings.

An anonymous early biographer, known as Anonimo Gaddiano, claims that around 1480, Leonardo was living with the influential Medici family and frequently worked in the garden of the Piazza San Marco in Florence. This was the vibrant meeting place for a Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets, and philosophers organized by the Medici, placing Leonardo at the heart of the era’s intellectual and cultural ferment. His proximity to such minds undoubtedly fueled his own expansive intellectual pursuits and broadened his philosophical horizons.

In March 1481, he secured another important commission from the monks of San Donato in Scopeto for *The Adoration of the Magi*. However, neither this, nor the altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard, would be completed. These initial commissions were abandoned when Leonardo made a strategic decision: he went to offer his services to the powerful Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza. He famously sent Sforza a letter detailing his diverse capabilities in engineering and weapon design, almost as an afterthought mentioning that he could paint. He even brought a silver string instrument, either a lute or lyre, crafted in the form of a horse’s head, showcasing his blend of artistic flair and innovative craftsmanship. This bold move marked the end of his first Florentine chapter and the beginning of a new, ambitious phase in Milan.

Read more about: Unveiling Leonardo da Vinci: A Renaissance Titan’s Enduring Legacy Across Art, Science, and Engineering

4. **Milanese Patronage: First Milanese Period (c. 1482–1499)**

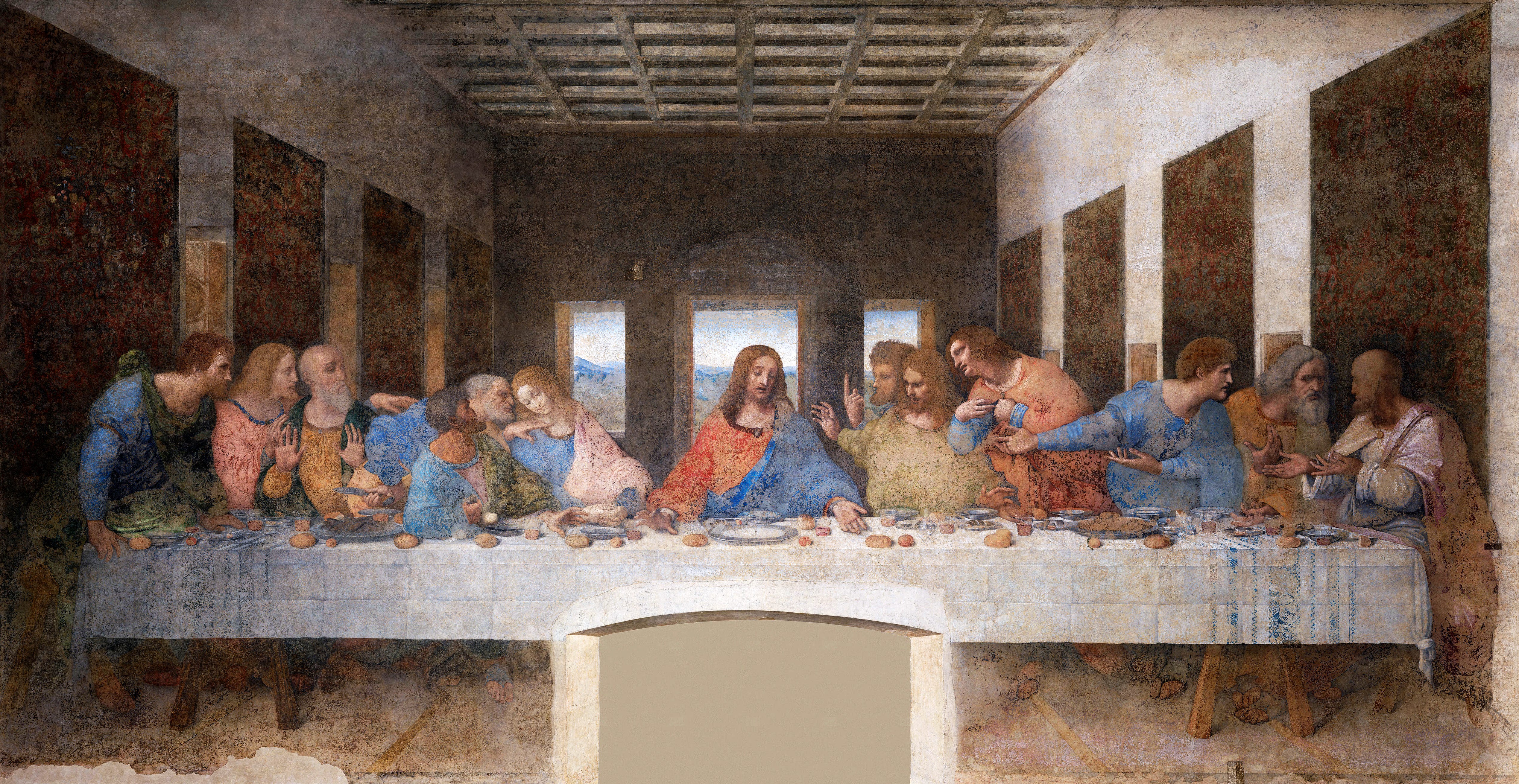

Leonardo’s move to Milan in 1482 ushered in a prolific period, lasting until 1499, where he found patronage under Ludovico Sforza. It was a time of immense creative output and diverse projects, allowing him to flex his artistic and engineering muscles. Among his most significant commissions were the painting of *The Virgin of the Rocks* for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and, perhaps most famously, *The Last Supper* for the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, works that would forever cement his legendary status.

His talents were not confined to Milan’s borders; in the spring of 1485, Leonardo even journeyed to Hungary on behalf of Sforza to meet King Matthias Corvinus, who commissioned him to paint a Madonna. This demonstrates the far-reaching reputation he was already cultivating across Europe. Later, in 1490, he was called as a consultant, alongside Francesco di Giorgio Martini, for the building site of the cathedral of Pavia, where he was so captivated by the equestrian statue of Regisole that he left behind a sketch, revealing his constant engagement with the artistic and architectural marvels around him.

Leonardo’s duties for Sforza were incredibly varied, ranging from the grand to the ceremonial. He prepared floats and pageants for special occasions, showcasing his flair for theatrical design. He also contributed a drawing and a wooden model for a competition to design the cupola for Milan Cathedral, further demonstrating his architectural ambitions. However, one of his most ambitious projects for Sforza was a model for a colossal equestrian monument to Ludovico’s predecessor, Francesco Sforza, a project that became famously known as the *Gran Cavallo*.

This intended monument would have been an unprecedented feat for the Renaissance, designed to surpass in size the only two large equestrian statues of the era: Donatello’s *Gattamelata* in Padua and Verrocchio’s *Bartolomeo Colleoni* in Venice. Leonardo poured his energy into this grand vision, completing a magnificent model for the horse and making meticulous, detailed plans for its casting. It was a testament to his engineering prowess and artistic ambition, a vision that captivated him and many others.

Tragically, in November 1494, circumstances intervened. Ludovico Sforza, facing the threat of Charles VIII of France, made the difficult decision to give the metal that had been earmarked for the *Gran Cavallo* to his brother-in-law, to be melted down and used for cannons to defend the city. This poignant twist of fate meant Leonardo’s monumental sculpture, a dream of years, would never be realized in bronze, a stark reminder of how political realities could impact artistic endeavors even for a genius of his caliber.

Contemporary correspondence records another significant commission: around 1498, Leonardo and his assistants were tasked by the Duke of Milan to paint the Sala delle Asse in the Sforza Castle. This project transformed into a spectacular *trompe-l’œil* decoration, making the great hall appear as if it were a grand pergola, meticulously created by the interwoven limbs of sixteen mulberry trees. The intricate labyrinth of leaves and knots on the ceiling completed the illusion, turning the space into an immersive, naturalistic marvel, further showcasing Leonardo’s innovative approach to decorative art.

5. **Return to Florence: Second Florentine Period (1500–1508)**

The political landscape of Italy was constantly shifting, and in 1500, when Ludovico Sforza was overthrown by France, Leonardo found himself once again on the move. He fled Milan, seeking refuge first in Venice, accompanied by his loyal assistant Salaì and his friend, the mathematician Luca Pacioli. In Venice, his diverse talents were immediately recognized and put to use; he was employed as a military architect and engineer, devising crucial methods to defend the city from potential naval attacks. His genius was not limited to aesthetics but extended to vital strategic defense.

Upon his return to Florence in 1500, Leonardo and his household found hospitality as guests of the Servite monks at the monastery of Santissima Annunziata. There, he was provided with a workshop, where, according to Vasari, he created the cartoon of *The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist*. This work garnered such immense admiration that “men [and] women, young and old” flocked to see it “as if they were going to a solemn festival.” This period marked a triumphant return to his artistic roots in Florence, with the public eager to witness his latest creations.

His restless spirit and practical skills soon led him to new challenges. In Cesena in 1502, Leonardo entered the service of Cesare Borgia, the ambitious son of Pope Alexander VI. Acting as a military architect and engineer, Leonardo traveled throughout Italy with his patron, engaging in vital strategic work. He famously created a detailed map of Cesare Borgia’s stronghold, a town plan of Imola, a remarkable feat of cartography designed to win Borgia’s patronage. Impressed by his brilliance, Cesare promptly hired Leonardo as his chief military engineer and architect, placing immense trust in his innovative mind.

Later in the same year, Leonardo produced another significant map for his patron: one of the Chiana Valley in Tuscany. This highly accurate map was designed to give Borgia a superior overview of the land and a greater strategic position in military campaigns. Demonstrating his multi-faceted engineering prowess, he created this map in conjunction with another ambitious project: the construction of a dam from the sea to Florence, intended to ensure a consistent supply of water to sustain a canal throughout all seasons. His vision for urban planning and resource management was truly ahead of its time.

Leonardo had left Borgia’s service and returned to Florence by early 1503, rejoining the Guild of Saint Luke on October 18 of that year. It was in this very month that he commenced work on a portrait that would become arguably the most famous painting in the world: the *Mona Lisa*, or *La Gioconda*. He would continue to work on this enigmatic masterpiece for many years, perfecting its subtle nuances. In January 1504, he was part of an influential committee formed to recommend the ideal placement for Michelangelo’s monumental statue of David, a testament to his respected artistic judgment. He then spent two years in Florence, dedicating his formidable talents to designing and painting a mural of *The Battle of Anghiari* for the Signoria, a dramatic companion piece to Michelangelo’s *The Battle of Cascina* on the opposite wall.

6. **Scientific Pursuits in Milan: Second Milanese Period (1508–1513)**

By 1508, Leonardo was once again drawn back to Milan, a city that had previously provided him with ample opportunities for both artistic and scientific endeavors. He settled into his own house in Porta Orientale, within the parish of Santa Babila, signaling a period of renewed stability and focused work. This return marked another chapter where his insatiable curiosity would lead him down new paths, blending his artistic genius with rigorous scientific investigation.

In 1506, he had been summoned to Milan by Charles II d’Amboise, who was the acting French governor of the city. It was during this time that Leonardo took on another important pupil, Count Francesco Melzi, the son of a Lombard aristocrat. Melzi would become much more than just a student; he is widely considered to have been Leonardo’s favorite pupil, developing a deep and lasting bond with the master, and eventually becoming his principal heir and executor.

The Council of Florence, still keen on seeing *The Battle of Anghiari* finished, wished for Leonardo to return promptly. However, he was granted leave at the behest of Louis XII, who considered commissioning the artist to make several portraits. This period of patronage from the French afforded Leonardo a unique freedom. He may have commenced a project for an equestrian figure of d’Amboise, and while a wax model attributed to him survives (though its attribution is not universally accepted), it would be the only extant example of Leonardo’s sculptural work. Such projects continued to showcase his mastery across various mediums.

Crucially, this period in Milan allowed Leonardo to pursue his scientific interests with renewed vigor, unburdened by the demands of major Florentine commissions. It was a time of deep study and exploration, where his notebooks likely swelled with observations on anatomy, botany, and mechanics. Many of Leonardo’s most prominent pupils either knew or worked with him during this Milanese sojourn, including Bernardino Luini, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, and Marco d’Oggiono, further solidifying the artistic legacy he was cultivating.

In 1507, Leonardo briefly returned to Florence to address a more personal matter: sorting out a dispute with his brothers over the estate of his father, who had passed away in 1504. Even a genius of Leonardo’s stature was not immune to the ordinary complexities of family affairs and legal proceedings. By 1512, he was back in Milan, diligently working on plans for another grand equestrian monument, this time for Gian Giacomo Trivulzio. However, this ambitious project, much like the *Gran Cavallo*, was ultimately prevented by the tumultuous political climate, as an invasion by a confederation of Swiss, Spanish, and Venetian forces drove the French from Milan. Leonardo, ever resilient, remained in the city, spending several months in 1513 at the Medici’s Vaprio d’Adda villa, awaiting his next move.

7. **Final Years in Rome and France (1513–1519)**

The political currents of Italy once again dictated Leonardo’s next move. In March 1513, Lorenzo de’ Medici’s son, Giovanni, assumed the papacy as Leo X, creating new opportunities. Leonardo traveled to Rome that September, where he was warmly received by the Pope’s brother, Giuliano. From September 1513 to 1516, Leonardo spent a significant portion of his time living in the Belvedere Courtyard within the Apostolic Palace, a vibrant artistic hub where Michelangelo and Raphael were also actively working. He was truly among giants.

During his time in Rome, Leonardo received an allowance of 33 ducats a month, which certainly supported his continued experimentation and study. Vasari recounts a charming, if eccentric, anecdote from this period: Leonardo reportedly decorated a lizard with scales dipped in quicksilver, a whimsical testament to his playful curiosity and delight in the natural world. The Pope himself gave Leonardo a painting commission of an unknown subject matter, but, in a curious turn of events, cancelled it when the artist decided to embark on developing a new kind of varnish, prioritizing his scientific inquiry over a direct artistic assignment.

It was in Rome that Leonardo faced significant health challenges, becoming ill in what may have been the first of multiple strokes that would ultimately lead to his death. Despite these setbacks, his intellectual drive remained undiminished. He diligently practiced botany in the extensive Vatican Gardens, meticulously observing and documenting plant life, further enriching his already vast notebooks. He was also commissioned to make plans for the Pope’s proposed draining of the Pontine Marshes, a testament to his continued recognition as a brilliant civil engineer.

His scientific pursuits extended to human anatomy; he dissected cadavers, making detailed notes for a treatise on vocal cords. In an effort to regain the Pope’s favor, he gave these valuable notes to an official, though unfortunately, his efforts were unsuccessful. This reveals a period of personal and professional difficulty for the master, even amidst his groundbreaking research.

October 1515 saw King Francis I of France successfully recapture Milan, marking another shift in the European power balance. On March 21, 1516, Antonio Maria Pallavicini, the French ambassador to the Holy See, received a letter from Guillaume Gouffier, a royal advisor, with exciting news. The letter contained the French king’s instructions to assist Leonardo in his relocation to France, eagerly awaiting his arrival, and reassuring the artist that he would be well received at court by both the King and his mother, Louise of Savoy. It was a clear invitation to a new chapter.

Later that year, Leonardo officially entered Francis I’s service. He was granted the use of the picturesque manor house Clos Lucé, conveniently located near the King’s residence at the royal Château d’Amboise. King Francis I frequently visited Leonardo, a testament to their budding friendship and mutual admiration. During this time, Leonardo drew plans for an immense castle town that the King intended to erect at Romorantin, showcasing his continued architectural ambitions on a grand scale. He also famously created a mechanical lion, a marvel of engineering that, during a pageant, walked towards the King and, upon being struck by a wand, dramatically opened its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies, delighting the court and demonstrating his enduring ingenuity and flair for spectacle.

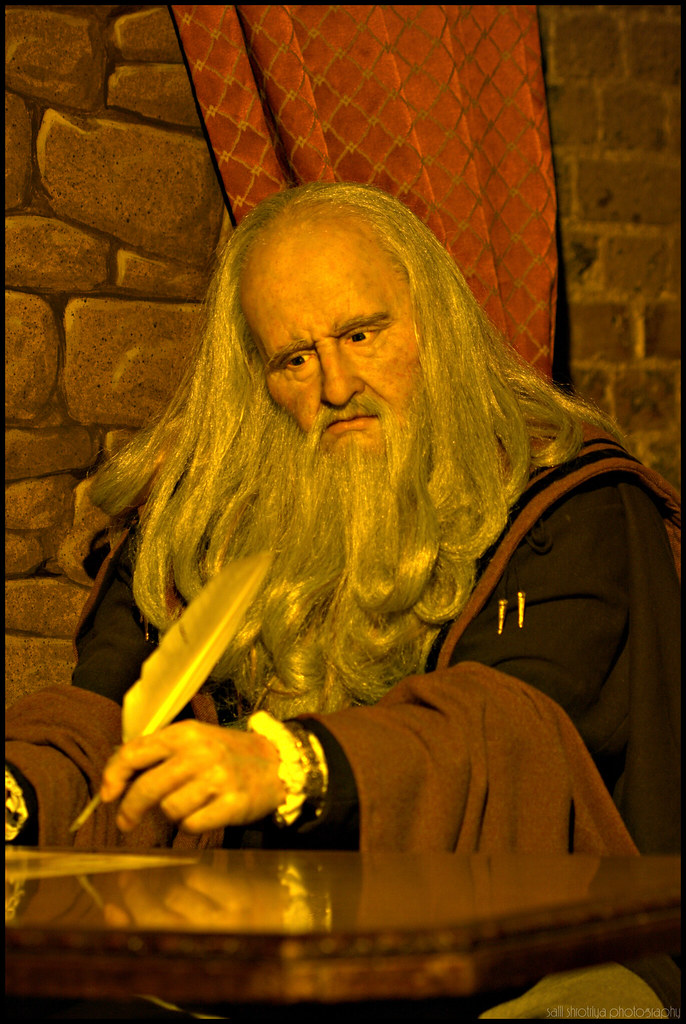

Throughout these final years, Leonardo was accompanied by his cherished friend and apprentice Francesco Melzi, who would stay with him until the end. He was supported by a generous pension totaling 10,000 scudi, ensuring his comfort and ability to continue his work. Melzi himself drew a portrait of Leonardo during this time, and other rare contemporary images, such as a sketch by an unknown assistant (c. 1517) and a drawing by Giovanni Ambrogio Figino depicting an elderly Leonardo with his right arm wrapped, suggest a growing physical frailty. A record from an October 1517 visit by Louis d’Aragon further confirms an account of Leonardo’s right hand being paralytic when he was 65, which may offer a poignant explanation for why he left some works, such as the *Mona Lisa*, unfinished. Despite his declining health, he continued to work in some capacity until eventually becoming ill and bedridden for several months, bringing his extraordinary journey to its quiet conclusion.

8. **The Final Chapter: Death in France (1519)**

Leonardo’s extraordinary journey through life found its peaceful conclusion at Clos Lucé, his manor home near King Francis I’s royal Château d’Amboise, on May 2, 1519. He was 67 years old, and it is believed that he passed away, possibly, from a stroke, after having been ill and bedridden for several months. His final years in France were marked by the warm hospitality and admiration of King Francis I, who had become a close friend and patron to the aging genius.

Historian Giorgio Vasari paints a poignant picture of Leonardo’s last moments, recounting that on his deathbed, the master was ‘full of repentance,’ lamenting ‘that he had offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as he should have done.’ Vasari also states that Leonardo sought a priest to confess and receive the Holy Sacrament, reflecting a deeply human desire for spiritual reconciliation at the end of a remarkable life. It’s a powerful image of a man, even one of such immense talent, grappling with his life’s work.

Adding to the dramatic narrative, Vasari famously records that King Francis I held Leonardo’s head in his arms as the great artist passed. While this touching story may be more legend than fact, it perfectly encapsulates the profound respect and affection the French monarch held for Leonardo. In a final testament to his character and compassion, Leonardo’s will stipulated that sixty beggars, each carrying tapers, should follow his casket, ensuring a humble and inclusive farewell.

9. **A Lasting Bond: Francesco Melzi, Heir to a Genius**

Beyond his public achievements, Leonardo’s will reveals the deep personal connections he forged throughout his life. Francesco Melzi, his cherished friend and apprentice who had accompanied him until the very end, was named the principal heir and executor of his estate. Melzi received not only money but also Leonardo’s precious paintings, invaluable tools, an extensive library, and all his personal effects, a true measure of the master’s trust and affection.

This inheritance was a testament to the profound bond between teacher and student, highlighting Melzi’s steadfast loyalty and importance in Leonardo’s life. Melzi’s role in preserving Leonardo’s notebooks and facilitating their study after his death cannot be overstated; he became the steward of an unparalleled intellectual treasure, ensuring Leonardo’s genius would be accessible to future generations.

While Melzi received the lion’s share, Leonardo also remembered others close to him. Salaì, his other long-time pupil and companion, along with his servant Baptista de Vilanis, each received half of Leonardo’s vineyards. His brothers, with whom he had a somewhat distant relationship, received land, and his serving woman was gifted a fur-lined cloak, showing a thoughtful consideration for all who served him in his later years. This division of assets paints a picture of a man who carefully considered the people in his life.

Twenty years after Leonardo’s passing, the renowned goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini shared a powerful quote from King Francis I, demonstrating the enduring impact of Leonardo’s intellect. The king reportedly said, “There had never been another man born in the world who knew as much as Leonardo, not so much about painting, sculpture and architecture, as that he was a very great philosopher.” This glowing tribute from a monarch underscores Leonardo’s unparalleled status as a thinker whose contributions transcended the boundaries of art.

10. **Unveiling the Man: Personal Life and Enigmatic Relationships**

Despite the thousands of pages filled with intricate drawings and meticulous notes in his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci scarcely made direct reference to his personal life, leaving much to historical interpretation and speculation. This privacy, however, only amplified the curiosity of his contemporaries and those who followed, especially concerning his “great physical beauty” and “infinite grace,” as famously described by Vasari.

One delightful aspect of his personal life, recounted by Vasari, was Leonardo’s deep love for animals. He was known to purchase caged birds, not to keep them, but to set them free, a tender act that hints at a profound compassion and perhaps even a vegetarian lifestyle. This empathetic connection to the natural world offers a glimpse into the gentle soul behind the formidable intellect.

While Leonardo cultivated many notable friendships throughout his life, including a productive collaboration with mathematician Luca Pacioli on *Divina proportione*, his romantic relationships remain largely veiled. He appears to have had no close romantic ties with women, though he shared friendships with figures like Cecilia Gallerani and the Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella, for whom he once drew a portrait during a journey through Mantua. These connections suggest a preference for intellectual companionship.

However, the subject of Leonardo’s uality has been a topic of intense discussion and speculation since the mid-16th century, a trend notably revived by Sigmund Freud in his *Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood*. It is widely believed that his most intimate relationships were with his pupils, Salaì and Francesco Melzi. Melzi, in a letter to Leonardo’s brothers informing them of his death, described the master’s feelings for his pupils as both “loving and passionate.”

Historical claims since the 16th century have suggested that these relationships were of a ual or erotic nature. Walter Isaacson, in his biography of Leonardo, even explicitly states his opinion that the relations with Salaì were “intimate and homosexual.” This perspective is further supported by historical records from 1476, when Leonardo, at age twenty-four, and three other young men were charged with sodomy involving a known male prostitute. Though the charges were dismissed due to lack of evidence—with some speculating that the powerful Medici family intervened—this incident has significantly fueled discussions about his presumed homosexuality and its potential influence on his art, particularly in the striking androgyny and subtle eroticism found in works like *Saint John the Baptist* and certain erotic drawings.

Read more about: The Enduring Legacy: A Deep Dive into the Visionary World of Leonardo da Vinci’s Masterpieces and Mind

11. **The Painter: Unrivaled Masterpieces and Pioneering Techniques**

For nearly four centuries, Leonardo da Vinci’s fame primarily rested upon his extraordinary achievements as a painter, a reputation that has only recently expanded to fully encompass his scientific and inventive genius. His handful of authenticated or attributed major works are universally regarded as some of the greatest masterpieces in the history of Western art, continuing to inspire awe and critical discussion to this day.

By the 1490s, the art world had already recognized his unparalleled talent, describing him as a “Divine” painter, a testament to the profound impact of his artistry. His paintings are celebrated for a captivating blend of qualities that set them apart, making them objects of endless study and imitation by students across generations. He truly changed the game with his brush.

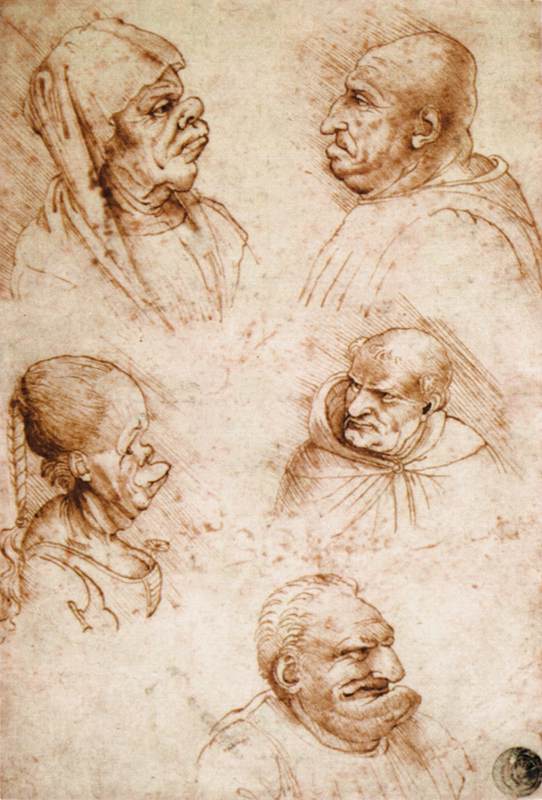

What makes Leonardo’s painted works truly unique is his innovative approach to applying paint, a revolutionary technique for his time. His meticulous, detailed knowledge of human anatomy, the nuanced play of light, the intricacies of botany, and the grand sweep of geology are all vividly integrated into his compositions. He possessed a keen interest in physiognomy, capturing the subtle ways humans express emotion through facial expressions and gestures, breathing incredible life into his subjects.

Moreover, Leonardo pioneered the innovative use of the human form within figurative compositions, creating dynamic and emotionally charged scenes. His masterful deployment of subtle gradation of tone, famously known as *sfumato* or “Leonardo’s smoke,” allowed him to create an atmospheric depth and softness that was utterly groundbreaking. These combined qualities converge magnificently in his most iconic painted works, including the *Mona Lisa*, *The Last Supper*, and *The Virgin of the Rocks*, solidifying his place as an artistic titan.

12. **The *Mona Lisa*: An Enduring Icon of Mystery**

Among Leonardo’s incredible oeuvre, the small portrait known as the *Mona Lisa*, or *La Gioconda*—meaning “the laughing one”—stands alone as arguably the most famous painting in the entire world. It is, without question, his best-known work and the most celebrated individual painting, captivating millions with its enduring mystique and elusive charm. No matter where you go, her smile is recognized.

Its unparalleled fame rests, in large part, on the enigmatic smile gracing the woman’s face, a smile whose mysterious quality is perhaps due to the subtly shadowed corners of her mouth and eyes. This artistic genius creates an effect where the exact nature of her expression cannot be definitively determined, inviting endless contemplation and interpretation from every viewer. It is a testament to the power of suggestion in art.

This shadowy quality, for which the work is so renowned, came to be known as *sfumato*, or “Leonardo’s smoke,” a technique that softens outlines by subtle gradation of tone and color, creating a hazy, dreamlike effect. Vasari, deeply impressed, wrote that the smile was “so pleasing that it seems more divine than human, and it was considered a wondrous thing that it was as lively as the smile of the living original.” His words still resonate with the painting’s powerful allure today.

Other notable characteristics contribute to the painting’s iconic status, such as the unadorned dress of the sitter, which wisely ensures that the viewer’s attention remains fixed on her captivating eyes and hands, undisturbed by extraneous details. The dramatic landscape background, rendered with a sense of the world in constant flux, adds another layer of intrigue, placing the serene figure against a vast, dynamic natural world. The subdued coloring further enhances its timeless appeal.

Furthermore, the extremely smooth nature of Leonardo’s painterly technique is a marvel in itself, employing oils laid on much like tempera and blended so seamlessly on the surface that individual brushstrokes are virtually indistinguishable. Vasari famously expressed that the painting’s quality would make even “the most confident master… despair and lose heart.” The *Mona Lisa*’s perfect state of preservation, with no discernible signs of repair or overpainting, is remarkably rare for a panel painting of its age, a true marvel that speaks to its careful stewardship throughout history.

13. **Iconic Narratives: *The Last Supper* and *Vitruvian Man***

Beyond the *Mona Lisa*, two other works by Leonardo da Vinci hold immense cultural significance and are instantly recognizable worldwide: *The Last Supper* and his drawing of *Vitruvian Man*. Each, in its own way, stands as a pillar of his artistic and intellectual legacy, continuing to inspire and educate across generations. They represent the pinnacle of his ability to capture both profound emotion and scientific precision.

*The Last Supper*, commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan, is undoubtedly the most reproduced religious painting of all time. It masterfully captures the dramatic moment when Jesus announces to his disciples, “one of you will betray me,” depicting the ensuing consternation and varied emotional responses of each individual. The psychological depth and narrative power of the composition are truly groundbreaking.

The creation of this monumental fresco, however, was not without its challenges and anecdotes. The writer Matteo Bandello observed Leonardo at work, noting that he would sometimes paint intensely from dawn till dusk without eating, only to then pause for three or four days, a working method that puzzled the convent’s prior. Vasari humorously recounts how Leonardo, struggling to find suitable models for the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas, even suggested using the exasperated prior as his model for the latter, showcasing his wit even amidst artistic struggle.

Despite its acclaimed status as a masterpiece of design and characterization, *The Last Supper* tragically deteriorated rapidly due to Leonardo’s experimental use of tempera over a gesso ground, rather than the more reliable fresco technique. Within a hundred years, it was described as “completely ruined” by one viewer. Yet, even in its fragile state, the painting remains one of the most reproduced works of art, inspiring countless copies and ensuring its story and emotional impact endure.

Then there’s the *Vitruvian Man*, a drawing that has transcended its origins to become a powerful cultural icon, embodying the Renaissance ideal of human proportion and the connection between art and science. This intricate drawing depicts a male figure in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart and simultaneously inscribed in a circle and square, a visual representation of human perfect symmetry and the universe’s order. It’s a symbol of human potential.

14. **The Visionary: Scientist and Engineer Beyond His Time**

While Leonardo’s fame for centuries rested primarily on his painting, modern awareness and admiration increasingly recognize his staggering contributions as a scientist and inventor. He was revered for his technological ingenuity, conceptualizing incredible machines far ahead of his time, a testament to a mind that saw no limits to human possibility. His notebooks reveal a world of boundless curiosity.

Imagine this: Leonardo conceptualized flying machines, a type of armored fighting vehicle (a precursor to the tank), concentrated solar power, a ratio machine that could be used in an adding machine, and even the double hull for ships. These were not mere whimsical sketches but detailed studies, demonstrating an astonishing foresight into future technological advancements. His brilliance truly knew no bounds.

It’s a poignant truth that relatively few of his designs were actually constructed or even feasible during his lifetime. The scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering were still in their infancy during the Renaissance, meaning the materials and techniques simply weren’t available to bring many of his grand visions to life. He was quite literally a man living in the future, constrained by his present.

Yet, not all his practical inventions remained unheralded. Some of his smaller, yet significant, innovations subtly entered the world of manufacturing. These included an automated bobbin winder and a machine designed for testing the tensile strength of wire, showcasing his pragmatic ingenuity even in less glamorous applications. His mind was always seeking to improve and innovate, no matter the scale.

Furthermore, Leonardo made substantial discoveries across a vast array of scientific fields: anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology. His detailed anatomical drawings, for instance, were groundbreaking in their accuracy and insight. However, because he did not publish his findings, these profound discoveries had little to no direct influence on subsequent science during his time, a lost opportunity that highlights the isolation of his genius. Despite this, his enduring legacy as a polymath whose curiosity bridged art and science remains unparalleled, cementing his place as an unparalleled figure in history.

Read more about: The Enduring Legacy: A Deep Dive into the Visionary World of Leonardo da Vinci’s Masterpieces and Mind

As we conclude our exploration of Leonardo da Vinci, it’s clear that his impact extends far beyond the canvas. He was a man who challenged conventions, pushed intellectual boundaries, and dreamt of a world not yet realized. From the mysterious smile of the *Mona Lisa* to the intricate workings of his mechanical designs, Leonardo invites us to look closer, to question, and to marvel at the boundless potential of the human spirit. His life story is a vibrant symphony of art, science, and profound human curiosity, a legacy that continues to resonate, reminding us that true genius knows no limits and constantly inspires us to see the world with new eyes.