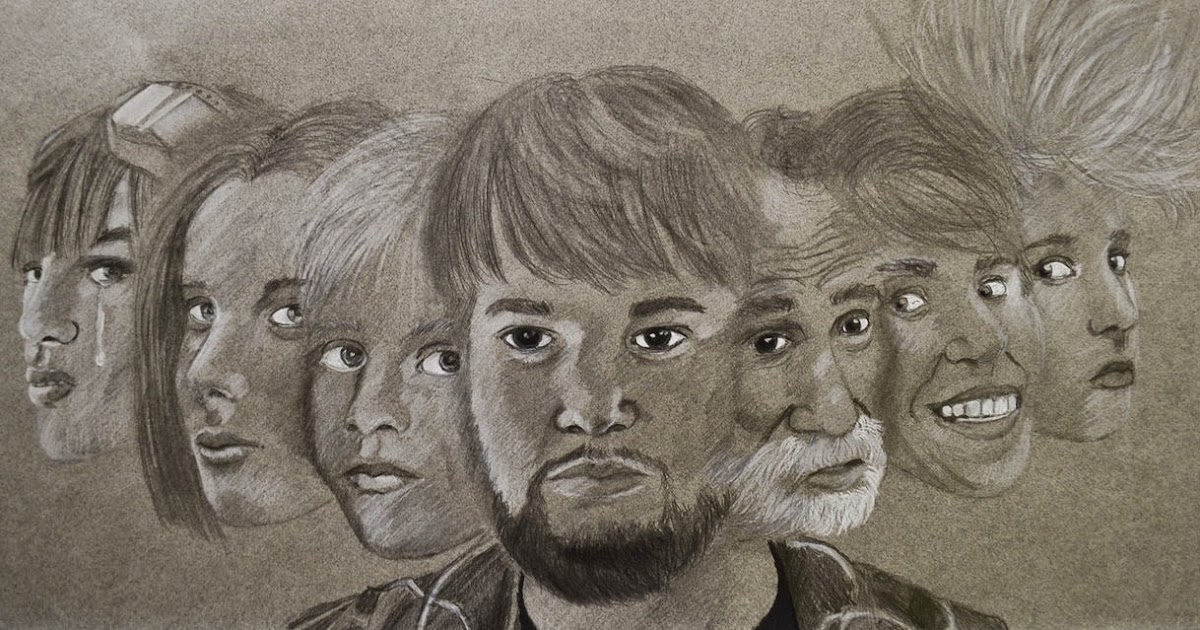

In the sprawling, often sensationalized landscape of mental health discourse, few conditions stir as much debate and misunderstanding as Dissociative Identity Disorder. Once widely known by its more dramatic moniker, Multiple Personality Disorder, DID has long captivated public imagination, fueled by dramatic cinematic portrayals and supposedly true stories like ‘Sybil’. These narratives, while compelling, have frequently overshadowed the complex, often harrowing reality of the disorder, contributing to a pervasive air of skepticism and fascination. The journey to comprehend DID is less a straightforward path and more a winding, sometimes disorienting, exploration into the very architecture of the self.

Far from a simple case of a ‘split personality’ – a term that itself redirects to DID in clinical contexts but often carries misinformed connotations in popular culture – this condition represents a profound fragmentation of identity and memory. It challenges our fundamental understanding of consciousness and personal continuity. For decades, clinicians, researchers, and patients have grappled with its elusive nature, trying to reconcile deeply personal experiences with scientific models that are still very much in contention. The sheer weight of differing theories, from its origins in early life trauma to its potential shaping by therapeutic and societal influences, makes DID one of psychiatry’s most contentious diagnoses.

So, what truly lies beneath the surface of Dissociative Identity Disorder? How do we distinguish fact from popular fiction, and clinical understanding from cultural constructs? This article delves into the intricate world of DID, examining its definitions, the harrowing array of symptoms, the competing theories regarding its causes, and the often-fraught process of its diagnosis. We’ll navigate the diagnostic minefield, explore the brain’s subtle whispers, and confront the fierce debates that continue to rage around this profoundly human, yet deeply enigmatic, condition. Prepare for an in-depth journey into the heart of a diagnosis that continues to perplex and provoke.

1. **Defining Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and Its Lexical Labyrinth**Dissociative Identity Disorder, previously termed Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD), stands as a condition characterized by the unequivocal presence of at least two distinct and enduring personality states, often referred to as ‘alters’. These ‘alters’ are not merely facets of a single personality but are described as relatively enduring, separate entities that recurrently take control of the individual’s behavior, often accompanied by significant memory gaps. The very foundation of this disorder, ‘dissociation,’ is conceptualized as a “compartmentalization of psychological functions such as identity and memory that are usually integrated.” This compartmentalization leads to a characteristic set of symptomatic criteria, marked by “unbidden intrusions into awareness and behavior, with accompanying losses of continuity in subjective experience” and/or an “inability to access information or control mental functions.”

The challenge of understanding DID begins with its terminology. Critics have frequently argued that the term ‘dissociation’ itself lacks a precise, empirical, and universally agreed-upon definition, proposing alternative frameworks such as an impairment in “meta-consciousness.” The experiences labelled as dissociative span a wide spectrum, from everyday failures in attention to the profound breakdowns in memory processes seen in dissociative disorders. This breadth raises questions about whether all dissociative experiences share a common underlying mechanism or if the varying severity reflects different etiologies and biological structures. Without a clear consensus, researchers and clinicians navigate a semantic minefield.

The definitional quagmire extends beyond ‘dissociation’ to other core terms pivotal in the study of DID, including ‘personality,’ ‘personality state,’ ‘identity,’ ‘ego state,’ and ‘amnesia,’ all of which also lack universally agreed-upon definitions. The absence of conceptual clarity complicates research and clinical practice, fostering multiple competing models that may include some non-dissociative symptoms while excluding others. To address this, terms like ‘ego state’ (behaviors and experiences with permeable boundaries, united by a common sense of self) and ‘alters’ (each potentially possessing separate autobiographical memory, independent initiative, and ownership over individual behavior) have been proposed, each attempting to capture the fragmented experience inherent in DID.

2. **The Unsettling Symphony of Symptoms: More Than Just ‘Alters’**While the presence of distinct personality states is the hallmark, the clinical presentation of Dissociative Identity Disorder encompasses a broader, more unsettling symphony of symptoms that can manifest at any age, though symptoms typically begin by ages 5–10, with the disorder generally developing in childhood. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) outlines key diagnostic criteria, including the “presence of two or more distinct personality states” alongside an inability to recall personal information that is more severe than ordinary forgetfulness. This memory impairment, often referred to as dissociative amnesia, is a total memory gap, affecting consciousness, basic bodily functions, perception, and all behaviors, and is subsumed under a DID diagnosis.

Beyond these core criteria, individuals with DID experience a profound loss of identity specifically related to individual distinct personality states, a disrupted subjective experience of the passage of time, and a degradation of their overall sense of self and consciousness. They may report inexplicable intrusions into their awareness, such as hearing voices, experiencing intrusive thoughts, impulses, or trauma-related beliefs. Furthermore, symptoms like depersonalization (feeling detached from one’s body or mental processes) and derealization (feeling detached from one’s surroundings) are commonly reported, contributing to a deeply fragmented sense of reality.

The clinical presentation varies significantly among individuals, with the level of functioning ranging from severe impairment to minimal disruption. A crucial aspect of the disorder is the asymmetrical nature of amnesia between identities; one ‘alter’ may or may not be aware of what another ‘alter’ knows, leading to significant functional challenges. Individuals often experience substantial distress not only from the direct symptoms like intrusive thoughts but also from the consequences, such as the inability to remember specific information or periods of time. A reluctance to discuss symptoms due to shame, fear, and associations with abuse is also common, making the hiddenness of the disorder a persistent barrier to care. While around half of patients have fewer than 10 identities, some reported cases have been as high as 4,500, with the average number increasing over time—a trend debated as either better recognition or increased acceptance within the psychiatric community.

3. **A Web of Woes: Understanding DID’s Comorbid Companions**The landscape of Dissociative Identity Disorder is rarely solitary; rather, it is frequently accompanied by a complex tapestry of comorbid psychiatric and neurological conditions, making accurate diagnosis and effective treatment particularly challenging. The person’s psychiatric history often reveals multiple previous diagnoses and a frustrating string of treatment failures, underscoring the pervasive and often refractory nature of the symptoms. Patients with DID are diagnosed with an average of 5-7 comorbid disorders, a significantly higher rate than observed in other mental health conditions.

The most prevalent presenting complaint among individuals with DID is depression, affecting approximately 90% of patients. This depression is frequently treatment-resistant, compounding the suffering and making stabilization difficult. Beyond mood disturbances, neurological symptoms are also common, including chronic headaches and non-epileptic seizures, which can sometimes lead to misdiagnoses. The spectrum of comorbid conditions is broad and includes post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use disorders, various eating disorders, a range of anxiety disorders, and other personality disorders. Notably, a significant proportion, between 30% and 70% of those diagnosed with DID, also have a history of borderline personality disorder, suggesting a complex interplay between identity fragmentation and personality dysregulation.

Disturbances in sleep patterns have also been implicated, with alterations to sleep suggested as playing a role in dissociative disorders generally and DID specifically. The distinction between DID and conditions like schizophrenia is crucial, particularly given that both can involve auditory hallucinations in the form of voices. However, presentations of dissociation in schizophrenia are typically not rooted in trauma, and the voices perceived by individuals with DID generally come from inside their heads, whereas those with schizophrenia often perceive voices as external. This intricate web of overlapping symptoms necessitates meticulous differential diagnosis, a task made even more difficult by the fact that clinicians often receive limited training in dissociative disorders, leading to diagnostic biases and initial misdiagnoses.

4. **The Trauma Model: A Scars-Deep Explanation**One of the two primary theoretical frameworks attempting to explain the genesis of Dissociative Identity Disorder is the trauma-related model, which posits DID as an organic response to severe childhood trauma. Proponents of this view often conceptualize DID as “the most severe form of a childhood-onset post-traumatic stress disorder,” asserting that complex trauma or severe adversity experienced in early childhood, typically before the ages of 5–6 years, represents a major risk factor for its development. The evidence supporting this model is substantial within the context of patient self-reports, with studies across diverse geographic regions indicating that 90% of individuals diagnosed with DID report experiencing multiple forms of childhood abuse, including rape, violence, neglect, or severe bullying.

Beyond interpersonal abuse, other traumatic childhood experiences are also reported, such as painful medical and surgical procedures, exposure to war or terrorism, attachment disturbances, natural disasters, cult or occult abuse, the loss of loved ones, human trafficking, and dysfunctional family dynamics. According to this model, the extreme stress and overwhelming nature of these traumatic events, particularly during critical developmental periods, cause awareness, memories, and emotions related to the harmful actions to be sequestered away from consciousness. This defensive mechanism then leads to the formation of alternate parts or identities, each holding differing memories, emotions, beliefs, temperaments, and behaviors, as a means of coping with unbearable reality.

The trauma model emphasizes that while adults might develop complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) after similar experiences, children, with their greater reliance on imagination as a coping mechanism and less integrated developmental personalities, may develop DID. Relationships between childhood abuse, disorganized attachment to caregivers, and a lack of social support are considered common risk factors. Furthermore, some evidence suggests a neurobiological impact of developmental stress, altering neuronal mechanisms related to memory. Though critics question the direct empirical link, proponents firmly believe that the high correlation of reported child abuse by adults with DID strongly corroborates the link between early trauma and the development of the disorder, viewing it as a profound, albeit fragmented, survival strategy.

5. **The Sociogenic Model: A Constructed Reality?**In stark contrast to the trauma model, the sociogenic (or fantasy) model of Dissociative Identity Disorder proposes a fundamentally different origin story, viewing the disorder not as an organic response to trauma but as a societal construct and learned behavior. This perspective suggests that DID can develop through a combination of high fantasy-proneness or suggestibility, role-playing, and, most controversially, through iatrogenesis—meaning the disorder is induced or shaped by the very therapy intended to treat it. Proponents of this model argue that unwitting therapists, particularly those specializing in DID and utilizing techniques such as hypnosis to “access” alter identities, facilitate age regression, or retrieve memories, provide subtle cues that shape or even create the diagnosis in suggestible individuals.

This model also highlights the role of broader sociocultural influences and media portrayals in perpetuating and shaping DID presentations. A frequently cited example supporting this theory is the popularization of DID in purportedly true books and films of the 20th century, notably ‘Sybil,’ which became foundational to many elements of the diagnosis but was later found to be extensively fictionalized. The idea is that behavior is enhanced and reinforced by exposure to such narratives, leading individuals, consciously or unconsciously, to adopt roles promoted by cultural stereotypes of dissociative identities.

Several arguments underpin the sociogenic model. Critics point to the rarity of DID diagnoses in children, a fact that challenges the early trauma model. They also note the dramatic spike in diagnosis rates after 1980, coinciding with increased media attention, rather than an observable increase in child abuse. The observation that the disorder appears almost exclusively in individuals undergoing psychotherapy, particularly involving hypnosis, is a significant plank of this argument. Furthermore, the reported presence of bizarre alternate identities (e.g., animals, mythological creatures) and an increase in the number of alters over time, especially at the start of DID-oriented therapy, are cited as evidence. A small subset of clinicians being responsible for diagnosing the majority of DID cases is also seen as supporting the idea of iatrogenic influence, raising concerns about the potential for suggestibility and high fantasization to predispose individuals to dissociation within therapeutic contexts.

6. **The Enigmatic Brain: Peering into DID’s Pathophysiology**Despite considerable research efforts employing advanced neuroimaging techniques—including structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), event-related potentials (ERPs), and electroencephalography (EEG)—a truly convergent set of neuroimaging findings specifically for Dissociative Identity Disorder remains elusive. The complexity of the disorder and its diverse presentations have made it challenging to pinpoint consistent neural correlates. However, one notable, albeit limited, finding that has emerged with some consistency is the observation of smaller hippocampal volume in DID patients, a structure critically involved in memory formation and emotional regulation. This particular finding hints at potential structural alterations, though its direct causal link to the dissociative symptoms remains a subject of ongoing investigation.

It is important to acknowledge that many of the existing neuroimaging studies on DID have been performed from an explicitly trauma-based position, which might influence the interpretation of results and the areas of the brain that researchers choose to investigate. Crucially, there is a notable absence of research to date specifically addressing the neuroimaging aspects related to the introduction of false memories in DID patients, or providing empirical support for amnesia occurring between alters through direct neural evidence. This gap in the literature highlights the difficulty in objectively verifying some of the subjective experiences central to the diagnosis, especially given the controversies surrounding memory retrieval in therapy.

Beyond structural differences, individuals diagnosed with DID appear to exhibit functional deficiencies in tests of conscious control of attention and memorization. These tests have also revealed signs of compartmentalization for implicit memory between alters, suggesting that unconscious memory processes might operate somewhat independently, although no such compartmentalization has been consistently demonstrated for verbal memory. Additionally, DID patients often show increased and persistent vigilance and exaggerated startle responses to auditory stimuli, which could be linked to a heightened state of arousal consistent with a trauma history. While the precise neuroanatomical alterations and their specific contributions to DID’s complex symptomatology are still being mapped, these preliminary findings suggest that the disorder may indeed involve tangible, albeit subtle, changes in brain structure and function.

7. **The Diagnostic Tightrope: Navigating the Minefield of DID Identification**The diagnosis of Dissociative Identity Disorder is undeniably a tightrope walk, fraught with potential missteps and significant controversy, even within the professional mental health community. The fifth, revised edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) outlines the formal criteria under code 300.14. However, the application of these criteria is often complicated by a stark reality: clinicians frequently receive insufficient training regarding dissociative disorders in general, and DID specifically. This lack of specialized education means that standard diagnostic interviews often neglect to include essential questions about trauma, dissociation, or post-traumatic symptoms, contributing significantly to difficulties in accurate diagnosis and to the pervasive issue of clinician bias.

The DSM-5-TR criteria stipulate that an individual must be recurrently controlled by two or more discrete identities or personality states, a condition that must be accompanied by memory lapses for important personal information. These memory gaps must be more extensive than ordinary forgetfulness and cannot be attributed to the effects of substances like alcohol, drugs, or medications, nor to other medical conditions such as complex partial seizures. A crucial differentiator, particularly in younger patients, is that for children, the symptoms must not be better explained by “imaginary playmates or other fantasy play,” emphasizing the pathological nature of the identity fragmentation.

Diagnosis is typically performed by clinically trained mental health professionals through a comprehensive clinical evaluation, which may involve interviews with family and friends, and consideration of ancillary materials. Specialized interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D), and personality assessment tools can also be employed to aid the process. Yet, because many symptoms rely heavily on self-report rather than concrete, observable signs, a degree of subjectivity inevitably enters the diagnostic process. This inherent ambiguity, coupled with individuals’ frequent reluctance to seek treatment due to shame or the fear that their symptoms won’t be taken seriously, has led some to refer to dissociative disorders as “diseases of hiddenness.” Critics, particularly those aligned with the sociocognitive hypothesis, further complicate the diagnostic landscape by asserting that DID is a culture-bound and often healthcare-induced condition, rather than a purely endogenous mental illness. This ongoing debate questions whether the observable symptoms truly reflect an internal pathology or are, at least in part, shaped by social cues within the diagnostic context, raising profound questions about the validity and stability of the diagnosis itself.

8. **Distinguishing the Shadows: Differential Diagnoses for DID**The bewildering tapestry of symptoms associated with Dissociative Identity Disorder often leads to a diagnostic odyssey, with patients frequently presenting with a history of multiple previous diagnoses and frustrating treatment failures. Clinicians face the formidable task of disentangling DID from a host of other conditions that share overlapping features, particularly given the average of 5-7 comorbid disorders typically found in DID patients—a rate significantly higher than in other mental health conditions. It’s a true diagnostic tightrope walk, demanding an expert eye to spot the subtle, yet crucial, distinctions.

Take, for instance, the often-confused relationship between DID and schizophrenia. Both conditions can involve auditory hallucinations in the form of voices, which can be easily mistaken for the speech of alternate personalities. However, a key differentiator lies in the origin of these perceived voices: in DID, voices generally emanate from inside the individual’s head, whereas those with schizophrenia typically perceive them as external. Moreover, the presentations of dissociation in schizophrenia are generally not rooted in trauma, and individuals with psychosis, unlike those with DID, are markedly less susceptible to hypnosis, providing a useful diagnostic wedge.

The diagnostic challenge extends to other significant disorders. Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) shares a considerable symptomatic overlap with DID, so much so that between 30% and 70% of individuals diagnosed with DID also have a history of BPD, leading some to suggest that DID may arise from a ‘substrate of borderline traits.’ Other conditions in the differential diagnosis include normal and rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, epilepsy (especially in cases with non-epileptic seizures, a common neurological symptom in DID), anxiety disorders, PTSD, and even autism spectrum disorder. The clinician’s ability to discern the persistence and consistency of identities, patterns of amnesia, and reports from family members regarding historical changes becomes paramount in untangling this complex web.

Ultimately, a diagnosis of DID takes precedence over any other dissociative disorders if criteria are met. Concerns about malingering—faking symptoms for external gain—or factitious disorder (attention-seeking) also enter the clinical consideration, though the core symptoms of DID are distinct. Crucially, individuals who attribute their symptoms to external spirits or entities are typically diagnosed with a dissociative disorder not otherwise specified, rather than DID, due to the absence of discrete internal identities. This meticulous diagnostic process, despite its inherent difficulties and the limited training many clinicians receive, is vital for ensuring appropriate care.

9. **The Battle for Belief: The Heated Validity Debate Surrounding DID**Few diagnoses in the psychiatric lexicon ignite as fierce a debate as Dissociative Identity Disorder, placing it squarely among the most controversial conditions in the DSM-5-TR. The core contention pivots on two fundamentally opposed models of its etiology: the trauma-related model versus the sociogenic (or fantasy) model. This isn’t merely an academic disagreement; it’s a battle for the very soul of the diagnosis, shaping how we understand, treat, and even acknowledge the profound suffering of those affected.

Proponents of the trauma model staunchly believe DID is a direct, organic response to severe childhood trauma, asserting that early, overwhelming adversity physically splits the mind into multiple identities, each harboring distinct memories and emotional experiences. They cite the overwhelming self-reported evidence of childhood abuse—rape, violence, neglect—among 90% of diagnosed individuals across diverse global regions. To them, DID is the most severe form of childhood-onset post-traumatic stress disorder, a fragmented survival strategy born from unbearable reality, and to deny this link is to invalidate the deep, lifelong impact of child abuse.

Conversely, critics, championing the sociogenic model, view DID as a societal construct, a learned behavior perhaps unknowingly induced or shaped by the therapeutic process itself. They argue that highly suggestible individuals, often with pre-existing psychopathology like borderline personality disorder, may unconsciously adopt roles promoted by cultural stereotypes, particularly when exposed to media portrayals or during intensive therapy involving techniques like hypnosis to ‘recover’ alters or repressed memories. This perspective casts a critical eye on the dramatic spike in diagnoses post-1980, coinciding with increased media attention, rather than a proven rise in actual trauma incidence, and notes the rarity of DID diagnoses in children as a challenge to the early trauma model.

The debate is further fueled by methodological criticisms. Some argue that the conceptual ambiguities inherent in terms like ‘personality state’ and ‘identity’ render DID impossible to diagnose accurately, while others point to internal consistency across specialized diagnostic interviews as evidence of its validity. The notion of ‘false memories’ also looms large, with concerns that therapeutic practices can inadvertently create or reinforce memories, though the ‘False Memory Syndrome’ itself is not recognized by mental health experts. Recent scholarly reviews, however, have noted a significant lack of empirical studies supporting the sociocognitive model in recent years, identifying it more as an unresolved critique than a standalone empirical hypothesis. This suggests a potential shift, with some major skeptics now moving towards ‘trans-theoretical’ models, acknowledging that trauma, in clinical cases, might indeed be more significant than sociocognitive factors, yet underscoring that no single model can fully account for the disorder’s complexities.

10. **Navigating the Path Forward: Treatment Approaches for DID**The journey toward managing Dissociative Identity Disorder is typically a long and arduous one, emphasizing comprehensive, integrative therapeutic approaches rather than quick fixes. While there are no direct medications to treat DID itself—after all, it’s not a chemical imbalance in the conventional sense—pharmacological interventions play a crucial supportive role. These are primarily directed at alleviating the frequently debilitating comorbid conditions, such as antidepressants for the severe, often treatment-resistant depression and anxiety that affect a vast majority of patients, or sedative-hypnotics to improve disturbed sleep patterns.

The cornerstone of DID treatment, however, is psychotherapy. This highly specialized form of therapy aims to help individuals navigate the fragmentation of their identity, address underlying trauma, and develop more adaptive coping mechanisms. Supportive care, which includes patient education and peer support, is also fundamental. Patients need to understand their condition, learn safety planning strategies to manage crises, and develop grounding techniques to mitigate dissociative episodes like depersonalization and derealization. Given the ‘hiddenness’ of the disorder, creating a safe, trusting therapeutic environment is paramount, as patients often harbor shame and fear about discussing their symptoms.

For those aligned with the trauma model, treatment often involves phased, trauma-informed therapy. This typically begins with stabilization and safety, building resources and coping skills before gradually processing traumatic memories. The ultimate goal is often integration or at least improved cooperation among alternate identities, fostering a more coherent sense of self. The challenge is immense, requiring clinicians with specialized training who can sensitively manage the intense emotional material and the dynamic interplay between alters, all while remaining vigilant for potential iatrogenic effects.

Conversely, for those who lean towards the sociogenic model, the therapeutic approach might diverge significantly. While acknowledging the genuine distress experienced by individuals, this perspective often focuses on de-emphasizing the notion of distinct ‘alters’ and instead aims to help individuals understand their symptoms as expressions of underlying distress influenced by external factors. Treatment may focus on reducing suggestibility, enhancing reality testing, and addressing pre-existing psychopathology like borderline personality disorder, without explicitly ‘working with’ or ‘accessing’ alters, which some believe could inadvertently reinforce the fragmented identities. Regardless of the theoretical lens, effective treatment hinges on a deep understanding of the individual’s unique presentation and a commitment to long-term, consistent care.

Read more about: Beyond the Read Receipt: Unpacking Why Gen Z Ghosts Their Friends and the Profound Future of Friendship

11. **The Long Road Ahead: Prognosis and the Lifelong Journey of DID**The prognosis for individuals diagnosed with Dissociative Identity Disorder is generally considered long-term, often necessitating a lifelong journey of therapeutic engagement and self-management. This isn’t a condition that typically remits spontaneously without intervention; indeed, the clinical consensus indicates that DID rarely resolves on its own. While the exact trajectory varies greatly among individuals, many patients, unfortunately, face a protracted course, underscoring the severity and entrenched nature of the disorder.

With appropriate and consistent treatment, particularly comprehensive psychotherapy, significant improvements in functioning and a reduction in distressing symptoms are absolutely achievable. The goal isn’t always complete integration of all alters into a single, unified personality—though that can be a desired outcome for some—but often focuses on fostering internal cooperation, improving communication among identity states, and enhancing overall daily functioning. This can lead to a more stable sense of self, better emotional regulation, and an improved ability to cope with the challenges of life.

However, the path to recovery is often punctuated by setbacks and requires immense resilience. The high comorbidity with other psychiatric conditions, particularly treatment-resistant depression and borderline personality disorder, complicates the prognosis, as managing these co-occurring issues is crucial for overall stability. Furthermore, the persistent stigma and misunderstanding surrounding DID can create additional barriers, making it difficult for individuals to seek and sustain treatment, or to find adequate social support. It’s a testament to the human spirit that many embark on this demanding journey, striving for a more integrated and peaceful existence despite the profound fragmentation they experience.

12. **The Numbers Game: Epidemiology and the Shifting Sands of Prevalence**When we talk about Dissociative Identity Disorder, the numbers themselves often tell a story of controversy and evolving understanding. According to epidemiological studies conducted in the US and Turkey, the lifetime prevalence of DID in the general population ranges between 1.1% and 1.5%. These figures are certainly not insignificant, suggesting that DID is more common than some might assume, and rise to about 3.9% among those admitted to psychiatric hospitals in Europe and North America. Yet, even these statistics are subject to debate, argued by various researchers to be both overestimates and underestimates, reflecting the ongoing contention surrounding the diagnosis itself.

A striking demographic pattern observed in DID is its higher prevalence in women, who are diagnosed 6–9 times more often than men. The reasons for this disparity are not fully understood but may relate to reporting biases, different coping mechanisms, or unique vulnerabilities. Historically, the number of recorded DID cases saw a significant increase in the latter half of the 20th century, particularly after 1980, a trend that coincided with greater media attention and the popularization of the disorder. This dramatic rise, alongside an increase in the number of identities reported by affected individuals (from an average of 2-3 to approximately 16 over time), remains a point of intense scrutiny.

It is unclear whether this increase in diagnosis rates is due to better recognition of the disorder by clinicians, greater acceptance within the psychiatric community of a high number of compartmentalized memory components, or, as the sociogenic model posits, due to sociocultural factors such as mass media portrayals that inadvertently shape symptom presentation. The very presentation of DID can also vary across cultures. For instance, in regions where normative possession states are common, fragmented identities might manifest as possessing spirits, deities, demons, animals, or mythical figures, rather than discrete internal personality states. This cultural influence underscores that DID is not just a biological or psychological phenomenon, but one deeply interwoven with social and cultural contexts.

13. **Shadows in Childhood: Unpacking DID’s Rarity and Implications in Young Patients**One of the most persistent and potent arguments wielded by critics of Dissociative Identity Disorder, particularly those advocating the sociogenic model, is the undeniable rarity of DID diagnoses in children. If DID is truly an organic response to early childhood trauma, as the trauma model suggests, why is it not more frequently identified in young patients, especially given that symptoms typically begin between ages 5-10, and the disorder generally develops in childhood? This glaring discrepancy serves as a critical point of contention, challenging the very foundation of the trauma-based etiology.

Indeed, proponents of both etiologies agree on one crucial point: the discovery of a child with DID who has never undergone treatment would critically undermine the non-trauma-related model, offering powerful evidence for an endogenous origin. Conversely, if children are found to develop DID only after therapeutic intervention, it would lend significant weight to the sociogenic view. As of 2011, approximately 250 cases of DID in children had been identified. However, this data does not unequivocally support either theory, as many of these children were presented to clinicians by parents already diagnosed with DID, or were influenced by popular culture portrayals, or initially diagnosed with psychosis due to hearing voices—a symptom common to DID but often misinterpreted.

The lack of general population studies seeking DID in children, and the reliance on examining siblings of already diagnosed individuals in the few existing studies, further muddies the waters. Critics of the trauma model highlight that the popular association of DID with childhood abuse is a relatively recent phenomenon, largely emerging after the 1973 publication of ‘Sybil,’ noting that earlier cases, such as Chris Costner Sizemore (‘The Three Faces of Eve’), reported no memory of childhood trauma. While the DSM-5-TR clearly states that ‘early life trauma… represents a major risk factor’ and explicitly differentiates DID in children from ‘imaginary playmates or other fantasy play,’ the rarity of its diagnosis in this crucial age group continues to be a profound riddle that neither causal model has fully resolved to universal satisfaction.

14. **Society’s Mirror: How Culture and Media Shape the Understanding of DID**The perception and understanding of Dissociative Identity Disorder are inextricably linked to the societal and cultural mirrors through which it is reflected, particularly the pervasive influence of popular culture, legal implications, and burgeoning online subcultures. From its emergence in purportedly true books and films of the 20th century, DID has been shaped, and arguably distorted, by narratives that have captivated the public imagination, often at the expense of nuanced clinical understanding.

The infamous case of ‘Sybil,’ for instance, became foundational to many elements of the DID diagnosis, yet was later found to be extensively fictionalized. This powerful media portrayal, among others, inadvertently contributed to the sociogenic model’s argument that cultural stereotypes can promote certain behaviors, leading individuals to consciously or unconsciously adopt roles aligned with fictional depictions. The rapid increase in DID diagnoses after 1980, coinciding with greater media attention, is cited as evidence for this sociocultural influence, suggesting a feedback loop where media popularizes the concept, potentially shaping symptom presentation and diagnostic trends.

Beyond media, cultural background significantly influences how DID manifests. The DSM-5-TR explicitly acknowledges this, noting that in cultural settings where normative possession states are common, fragmented identities may take the form of possessing spirits, deities, or mythical figures. Acculturation can also shape alter characteristics, with identities in some regions speaking exclusively English or wearing Western clothes. Distinguishing between culturally accepted possession states and pathological possession-form DID is crucial, with the latter being involuntary, distressing, and disruptive to an individual’s life. This highlights the complex interplay between internal pathology and external cultural frameworks.

Furthermore, the legal implications of DID are profound, particularly concerning issues of criminal responsibility, competence, and the reliability of recovered memories in legal proceedings. Online subcultures, too, have emerged, offering platforms for individuals to share experiences, seek validation, and potentially, some argue, even reinforce symptoms through shared narratives. This intricate web of cultural beliefs, media portrayals, legal battles, and digital communities continues to mold public perception and the lived experience of DID, making it a disorder as much defined by its context as by its clinical criteria.

15. **Echoes of the Past: A Brief History of DID and its Infamous Popularization**The history of Dissociative Identity Disorder is a fascinating, if contentious, narrative that traces its roots through centuries of medical inquiry, culminating in its infamous popularization in the 20th century. While early references to what might now be termed dissociative phenomena can be found throughout medical literature, the modern conceptualization and widespread recognition of DID, particularly under its former moniker, Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD), are largely a product of a specific historical period, deeply influenced by compelling, often dramatic, case studies and their subsequent media adaptations.

Before the mid-20th century, cases of ‘multiples’ were rare curiosities, occasionally documented but not widely recognized as a distinct diagnostic category. It was in the 20th century that the disorder truly entered the public consciousness. A pivotal moment arrived with the 1957 book and subsequent 1957 film, ‘The Three Faces of Eve,’ which chronicled the life of Chris Costner Sizemore. This portrayal, while dramatic, was significant for bringing the concept of multiple personalities to a broad audience, although it’s noteworthy that Sizemore herself reportedly had no memory of childhood trauma, a detail that complicates the later-dominant trauma model.

However, it was the 1973 book ‘Sybil,’ and its hugely popular 1976 television movie adaptation, that truly cemented the image of DID in the public imagination and, controversially, within the psychiatric community. ‘Sybil,’ purportedly a true story of a woman with 16 personalities stemming from severe childhood abuse, became foundational to many elements of the diagnosis and treatment approaches of the time. The sensational narrative powerfully reinforced the trauma model and propelled MPD into mainstream discourse, leading to a dramatic spike in diagnoses. The subsequent revelation that ‘Sybil’ was extensively fictionalized—a fabrication largely driven by the subject, her therapist, and the author—cast a long, dark shadow over the diagnosis, fueling the sociogenic model and intensifying the validity debate that continues to this day.

Despite the controversies and the historical baggage, the story of DID reflects a persistent human attempt to understand extreme psychological fragmentation. From its initial re-classifications in the DSM, evolving from MPD to DID, to the ongoing scientific and societal scrutiny, the disorder continues to challenge our understanding of identity, memory, and the intricate ways trauma, society, and the mind interact. It remains a powerful reminder of how cultural narratives can shape clinical realities, making its history as complex and multifaceted as the identities it describes.

As we conclude this exploration into the labyrinthine world of Dissociative Identity Disorder, it becomes strikingly clear that few conditions demand such a rigorous and empathetic intellectual engagement. From the intricate debates around its very existence to the profound impact of trauma and culture on its manifestation, DID stands as a testament to the complexities of the human psyche. It is a diagnosis that challenges the limits of our understanding, inviting continuous inquiry, critical analysis, and, above all, a commitment to shedding light on the shadows of identity.