The English language we speak today has a rich and complex history, a journey that stretches back over a millennium to its earliest recorded form: Old English. Often referred to as Anglo-Saxon, this ancient linguistic ancestor, spoken in England and parts of Scotland during the Early Middle Ages, might seem utterly foreign to modern ears. It is vastly different from Modern English and Modern Scots, largely incomprehensible without dedicated study, yet it forms the bedrock of our linguistic heritage.

Imagine delving into a language where about 85% of its words are no longer in use, but those that survived are the basic elements of Modern English vocabulary. This deep dive into Old English is more than just an academic exercise; it’s an exploration into the very soul of the English language, uncovering the forces that shaped its structure, sound, and spirit.

As we embark on this journey, we will explore the roots of its name, chart its historical progression from the Anglo-Saxon settlements to the Norman Conquest, map out its distinct regional dialects, examine the profound influence of other languages—especially Old Norse—and finally, dissect its unique phonological system and the significant sound changes that defined it. Understanding these elements is key to appreciating the robust foundation upon which our present-day language was built.

1. The Intriguing Etymology of “English” and the Angles

The very word “English” has roots deeply embedded in the early medieval period, directly stemming from “Englisċ,” the Old English term which meant ‘pertaining to the Angles.’ The Angles were one of the Germanic tribes, alongside the Saxons and Jutes, who played a pivotal role in settling many parts of Britain in the 5th century. By the 9th century, this designation had broadened to encompass all speakers of Old English, irrespective of whether they claimed Saxon or Jutish ancestry.

The origin of the name “Angles” itself is subject to fascinating hypotheses. One theory suggests it derives from Proto-Germanic “*anguz,” a term associated with narrowness, constriction, or anxiety, potentially referring to shallow coastal waters where these tribes resided or navigated. Alternatively, “*angô” could refer to curve or hook shapes, leading to the hypothesis that the Angles were named either for living on a fishhook-shaped promontory or because they were fishermen, ‘anglers.’

Regardless of the precise etymological path, the name “Englisċ” and its connection to the Angles highlights a crucial period of identity formation in Britain. This foundational naming underscores the deep historical ties between language, people, and place, laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the English nation and its language.

Read more about: Exploring the Power of Eight: A Deep Dive into Its Engineering, Performance, and Global Impact

2. Charting the Seven Centuries of Old English History

Old English was far from a static entity; its usage spanned a significant period of 700 years, from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century until the late 11th century, extending sometime after the Norman Conquest. While setting precise dates for linguistic periods can be an arbitrary process, linguist Albert Baugh dates Old English from 450 to 1150, characterizing it as a period of “full inflections” and a “synthetic language.”

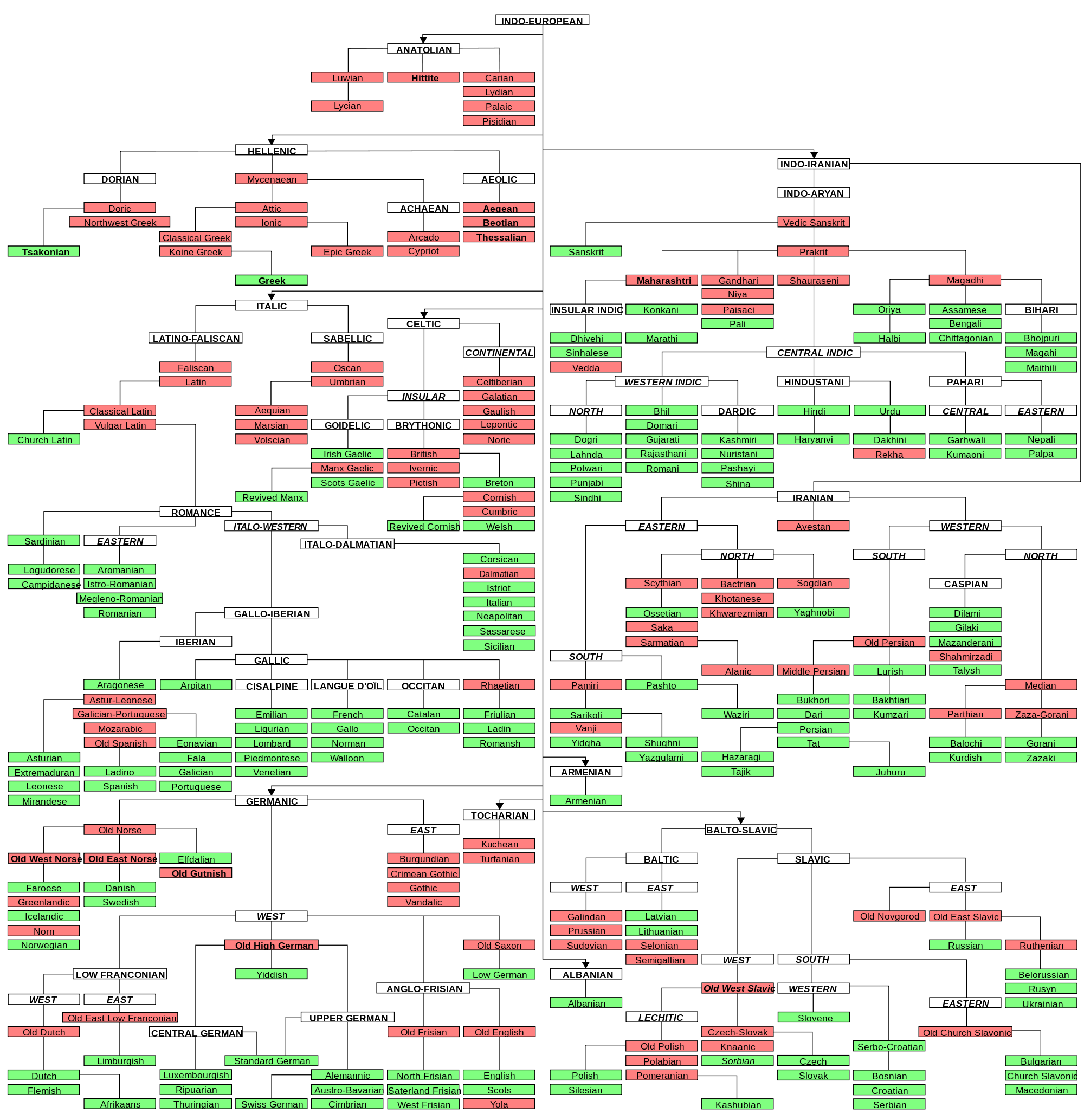

The origins of Old English lie in the North Sea Germanic dialects brought by the Germanic tribes—Angles, Saxons, and Jutes—from the 5th century onwards. As these settlers became dominant, their language gradually replaced the existing languages of Roman Britain, namely Common Brittonic (a Celtic language) and Latin. This linguistic dominance led to Old English being spoken across most of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, which eventually unified into the Kingdom of England, including parts of what is now southeastern Scotland.

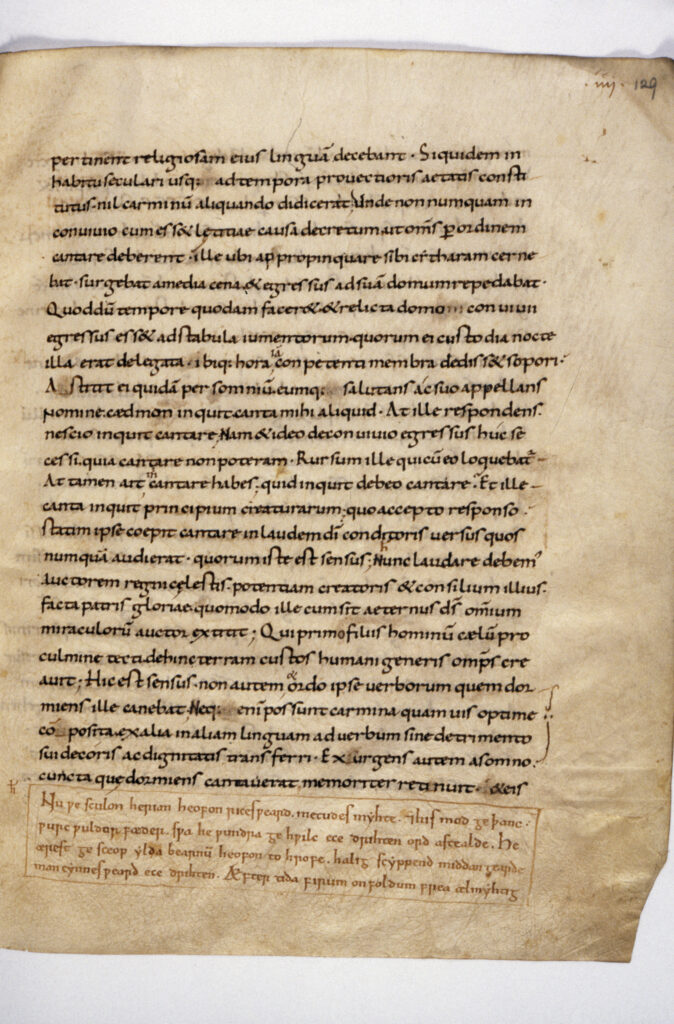

A pivotal moment in the development of Old English literacy occurred after the Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England in the late 7th century. The oldest surviving work of Old English literature, “Cædmon’s Hymn,” composed between 658 and 680, though not written down until the early 8th century, attests to this burgeoning literary tradition. Before this, a limited corpus of runic inscriptions existed, with the oldest coherent runic texts appearing in the early 8th century. The Latin alphabet, adapted for writing Old English, was introduced around the 8th century, largely replacing the runic system.

The 9th century saw another significant development with Alfred the Great’s unification of several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (outside the Danelaw). Alfred, a strong advocate for education, proposed that primary education be taught in English, with further studies in Latin reserved for those pursuing holy orders. He commissioned and personally participated in the translation of many works into English. Alfred’s influence was particularly instrumental in inspiring the growth of Old English prose, setting a precedent for a standardized language of government and literature around the West Saxon dialect (known as Early West Saxon).

The Old English period is typically subdivided into three phases: “Prehistoric Old English” (c. 450–650), for which the language is mostly reconstructed due to a lack of surviving literary witnesses. Following this is “Early Old English” (c. 650–900), marked by the oldest manuscript traditions and authors like Cædmon, Bede, Cynewulf, and Aldhelm. Finally, “Late Old English” (c. 900–1150) represents the language’s final stage before the Norman Conquest and its subsequent transition to Middle English and Early Scots, with the “Winchester standard” emerging as a “classical” form.

Read more about: Beyond the Theme Song: Unpacking the Universal Journey Through the Ages and Stages of Your Childhood

3. The Rich Tapestry of Old English Dialects

Just as Modern English exhibits considerable regional variation, Old English was far from monolithic, diverging according to geographical location. Despite the diverse linguistic backgrounds of the Germanic-speaking migrants who brought Old English to England and southeastern Scotland, scholars can reconstruct “proto-Old English” as a fairly unitary language. However, the observable differences between its regional dialects largely evolved within England and southeastern Scotland rather than originating from distinct continental forms.

The four principal dialectal forms of Old English were Mercian, Northumbrian, Kentish, and West Saxon. Collectively, Mercian and Northumbrian are often referred to as Anglian dialects, reflecting their association with the Angles. Geographically, the Northumbrian region lay north of the Humber River, while Mercian was situated between the Thames and the Humber. West Saxon dominated the area south and southwest of the Thames, and the smallest, Kentish region, settled by the Jutes, occupied a small corner southeast of the Thames.

While Old English writing from all regions tended to conform to a written standard based on Late West Saxon from the tenth century onwards, spoken Old English maintained significant local and regional variations. These spoken differences persisted into the Middle English period and, to some extent, are still discernible in modern English dialects. The scantest literary remains belong to the Kentish region, offering fewer insights into its specific linguistic traits.

The term “West Saxon” itself represents two distinct dialects: Early West Saxon and Late West Saxon. Some scholars, like Hogg, have suggested renaming these “Alfredian Saxon” and “Æthelwoldian Saxon” to prevent the misconception that they are chronological developments of one another. Each of these four dialects was originally associated with an independent kingdom. However, the 9th-century Viking invasions overran Northumbria (south of the Tyne) and most of Mercia. The successfully defended portion of Mercia and all of Kent were then integrated into Wes under Alfred the Great.

From this point, the West Saxon dialect, specifically Early West Saxon, became standardized as the language of government and the basis for a vast array of literature and religious texts translated from Latin. Despite the centralization of power and Viking destruction limiting non-West Saxon written records, Mercian texts continued to be produced, and Mercian influence is evident in many Alfredian translations, underscoring the enduring vitality of these regional speech patterns. In fact, what would become the standard forms of Middle and Modern English are descended from Mercian rather than West Saxon, with Scots developing from Northumbrian.

Read more about: The Enduring Power of a Name: Unveiling the Lives and Latest Chapters of Notable Williams, from Royalty to Hollywood’s Beloved Icon

4. The Linguistic Melting Pot: Influences of Other Languages on Old English

Old English, despite its robust Germanic core, was not isolated; it existed within a dynamic linguistic environment that led to borrowings and structural influences from other languages. Understanding these interactions is crucial to appreciating its evolution. The language of the Anglo-Saxon settlers appears not to have been significantly affected by native British Celtic languages, which it largely displaced. While some Celtic loanwords remained in western contact zones, various theories concerning Celtic influence on English syntax have generally not received widespread support from linguists.

Latin, however, had a more discernible impact as the scholarly and diplomatic lingua franca of Western Europe. Old English acquired some loanwords from Latin, with initial borrowings pre-dating the Angles’ arrival in Britain. A more significant influx occurred during the Christianization of the Anglo-Saxons, when influential Latin-speaking priests helped introduce the Latin alphabet via Irish missionaries, replacing the earlier runic system. It is important to remember that the largest transfer of Latin-based words, primarily through Old French, occurred later, in the Middle English period.

By far the most profound external influence on Old English came from Old Norse, contact initiated in the late 9th century through Scandinavian rulers and settlers in the Danelaw, continuing into the early 11th century. Many place names in eastern and northern England are of Scandinavian origin, evidencing this widespread interaction. While Norse borrowings were relatively rare in West Saxon-based Old English literature, their impact was much greater in the eastern and northern dialects, and becomes notably apparent in Middle English texts.

Simeon Potter keenly observed Old Norse’s “no less far-reaching” influence on the inflectional endings of English, noting how it “hastened that wearing away and leveling of grammatical forms.” This interaction between closely related Germanic languages, where speakers could roughly understand each other, led to inflectional differences becoming “obscured and finally lost,” simplifying English grammar. Modern English retains many everyday words from Old Norse, and this significant grammatical simplification is often attributed to Norse influence, making it arguably the greatest impact on the English language.

Read more about: Beyond the Border: Unpacking the Unique Canadian Identity That Often Gets ‘Mistaken for American’

5. Unraveling Old English Phonology and Its Sound Changes

The sound system of Old English possessed distinct characteristics in its consonant and vowel inventory, undergoing pivotal sound changes throughout its history. The inventory of Early West Saxon surface phones included a range of consonants, many with allophonic variations—sounds perceived as variants of the same phoneme, occurring in specific contexts. For instance, voiced allophones like [v, ð, z] appeared for /f, θ, s/ between vowels or voiced consonants when the preceding sound was stressed, demonstrating this complex phonetic reality.

Old English featured a comprehensive system of monophthongs (single vowel sounds) and diphthongs (gliding vowel sounds). Monophthongs spanned front and back, unrounded and rounded vowels across close, mid, and open categories. An allophone like [ɒ] occurred in stressed syllables before nasals, sometimes spelled ⟨a⟩ or ⟨o⟩. Anglian dialects notably had the mid front rounded vowel /ø(ː)/, emerging from i-umlaut, though it later merged with /e(ː)/ in West Saxon and Kentish.

The diphthongs were also a significant part of the Old English soundscape, presenting both short (monomoraic) and long (bimoraic) forms, such as /iy̯, iːy̯, eo̯, eːo̯, æɑ̯, æːɑ̯/. Different dialects had their own systems; for instance, Northumbrian retained /i(ː)o̯/, which had merged with /e(ː)o̯/ in West Saxon. This intricate phonological system allowed for a rich spoken language, even if many sounds have since been lost or transformed in Modern English.

The linguistic evolution of Old English was profoundly shaped by several principal sound changes. Key among these were “Anglo-Frisian brightening,” involving the fronting of [ɑ(ː)] to [æ(ː)], and the monophthongisation of the diphthong [ai]. Other significant phonetic transformations included “breaking,” which diphthongised certain front vowels, and “palatalization,” a crucial shift where velar consonants like [k] and [ɡ] changed into palatal sounds such as [tʃ] and [dʒ] in specific vowel environments.

Another vital process was “i-mutation,” responsible for vowel shifts like in “mouse” to “mice,” where a suffix vowel influenced a preceding root vowel. Further changes involved the loss and reduction of certain weak and unstressed vowels, “back mutation” causing diphthongisation before back vowels, and the loss of /x/ in some contexts, often with preceding vowel lengthening. These collective shifts refined Old English’s intricate sound patterns, contributing to its distinct pronunciation.

Continuing our deep dive into the earliest recorded form of our language, we now turn our attention to the intricate structural underpinnings and enduring impact of Old English. This section will systematically unpack its complex grammar, unique writing systems, significant literary contributions, the development of its scholarly tools, and its lasting legacy that quietly resonates in the English we speak today. Understanding these facets provides an even clearer picture of how a seemingly alien language transformed into the global communication tool it is now.

6. The Intricacies of Old English Grammar and Morphology

Old English grammar featured a complex system of inflections that significantly shaped its word order and meaning. Nouns, for instance, declined for five cases—nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, and instrumental—and distinguished between masculine, feminine, and neuter genders, as well as singular and plural numbers. These nouns were also categorized as either strong or weak. While the instrumental case was vestigial and primarily used with masculine and neuter singular forms, it was often replaced by the dative, with only pronouns and strong adjectives fully retaining separate instrumental forms. Early Northumbrian texts even offer sparse evidence of a sixth case, the locative, as seen in the phrase “on rodi” meaning ‘on the Cross’.

Adjectives in Old English exhibited agreement with nouns in case, gender, and number, and like nouns, could be either strong or weak, with weak endings typically used when a definite or possessive determiner was present. Pronouns and sometimes participles also agreed in these categories. Interestingly, first-person and second-person pronouns occasionally distinguished dual-number forms, a feature absent in Modern English. The definite article ‘sē’ and its various inflections served multiple roles, functioning as a definite article (‘the’), a demonstrative adjective (‘that’), and a demonstrative pronoun. Other demonstratives included ‘þēs’ (“this”) and ‘ġeon’ (“that over there”), all of which inflected for case, gender, and number.

Remarkable remnants of this robust Old English case system can still be observed in Modern English, particularly in the forms of certain pronouns, such as “I/me/mine” and “she/her,” and “who/whom/whose.” Furthermore, the modern possessive ending “-‘s” directly derives from the Old English masculine and neuter genitive ending “-es.” It’s also worth noting that while the modern English plural ending “-(e)s” originates from the Old English “-as,” the latter only applied to “strong” masculine nouns in the nominative and accusative cases, with distinct plural endings used in other instances. Old English nouns also possessed grammatical gender, a stark contrast to Modern English’s reliance on natural gender, meaning pronoun usage could reflect either natural or grammatical gender, as exemplified by the grammatically neuter noun “ƿīf” (/wiːf/), which meant “woman” (from “ƿīfmann,” meaning ‘woman person’ or ‘female person’) and eventually became the Modern English word ‘wife’.

Old English verbs conjugated for three persons, two numbers (singular and plural), and two tenses (present and past), along with three moods: indicative, subjunctive, and imperative. Verbs were largely divided into two great classes: strong verbs, which formed the past tense by altering the root vowel (a process known as ablaut), and weak verbs, which utilized a dental suffix. As in Modern English, this distinction between weak (regular) and strong (irregular) verbs was peculiar to the Germanic languages. Old English also featured two infinitive forms—bare and bound—and two participles—present and past, with the subjunctive mood having both past and present forms. Finite verbs consistently agreed with their subjects in person and number, while the future tense, passive voice, and other aspects were formed through compound constructions, marking the early beginnings of the compound tenses seen in Modern English. Many strong verbs present in Old English have, over time, decayed into weak forms, but the fundamental principle of dental suffixes indicating the past tense of weak verbs, as in ‘work’ and ‘worked’, persists.

In terms of syntax, Old English shared many similarities with modern English, yet exhibited some key differences largely stemming from its richer system of nominal and verbal inflection, which permitted a freer word order. The default word order was verb-second in main clauses and verb-final in subordinate clauses. Unlike Modern English, Old English did not employ ‘do’-support in questions and negatives. Instead, questions were typically formed by inverting the subject and the finite verb, and negatives were constructed by placing ‘ne’ before the finite verb, irrespective of the verb itself. A notable feature was also the ability of multiple negatives to stack up in a sentence, intensifying each other, a phenomenon known as negative concord.

Furthermore, sentences containing subordinate clauses of the type “when X, Y” (e.g., “When I got home, I ate dinner”) did not utilize a ‘wh’-type conjunction. Instead, they employed a ‘th’-type correlative conjunction such as “þā,” which otherwise meant “then” (e.g., “þā X, þā Y” in place of “when X, Y”). In Old English, ‘wh’-words (or “hw-words”) were used exclusively as interrogatives and indefinite pronouns. Similarly, ‘wh’-forms were not used as relative pronouns; instead, the indeclinable word “þe” was used, often preceded by, or sometimes replaced by, the appropriate form of the article or demonstrative “se.” These syntactic structures underscore the language’s distinct yet systematic framework.

Read more about: Unpacking Womanhood: 14 Key Aspects of Being a Woman Through History and Science

7. Old English Orthography: Runes to Latin Alphabet

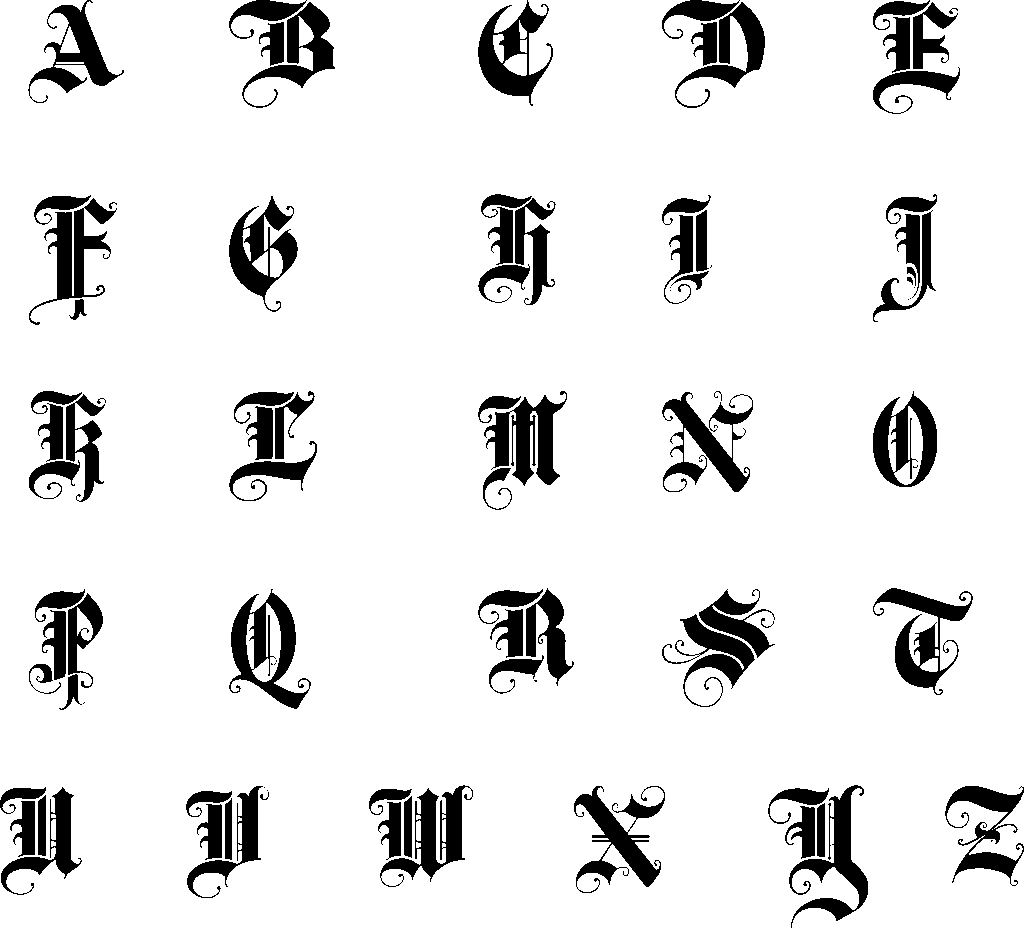

Old English’s writing systems underwent a significant transformation, initially employing runes before largely adopting the Latin alphabet. The earliest forms of Old English were inscribed using the futhorc, a runic alphabet derived from the 24-character Germanic elder futhark. This runic set was extended with at least five additional runes specifically designed to represent Anglo-Saxon vowel sounds, and sometimes even more characters were added to accommodate the language’s phonetic range. These runic inscriptions, though limited in corpus from the 5th to 7th centuries, provide some of the earliest textual evidence of Old English.

However, from around the 8th century, the runic system began to be supplanted by a version of the Latin alphabet. This shift was largely instigated by Irish Christian missionaries, who introduced a minuscule half-uncial script. This initial Latin script was subsequently replaced by Insular script, a more cursive and pointed variant of the half-uncial form. Insular script remained in use until the end of the 12th century, when it was ultimately superseded by the continental Carolingian minuscule, also known as Caroline, marking a further integration with broader European scribal traditions.

The Latin alphabet as adapted for Old English possessed some notable distinctions from modern conventions. It notably lacked the letters ⟨j⟩ and ⟨w⟩, and the letter ⟨v⟩ was not yet differentiated from ⟨u⟩. Furthermore, native Old English spellings did not typically utilize ⟨k⟩, ⟨q⟩, or ⟨z⟩. To compensate for sounds not represented by the standard 20 Latin letters, four additional characters were incorporated: ⟨æ⟩ (known as æsc, or modern ash) and ⟨ð⟩ (ðæt, now called eth or edh), both modified Latin letters, along with ⟨þ⟩ (thorn) and ⟨ƿ⟩ (wynn), which were borrowings directly from the futhorc runic system. A few letter pairs were also employed as digraphs to represent a single sound, enhancing the phonetic representation. Additionally, the Tironian note ⟨⁊⟩ (a character resembling the digit ⟨7⟩) was used as an abbreviation for the conjunction ‘and’, and a common scribal abbreviation was a thorn with a stroke ⟨ꝥ⟩ for the pronoun ‘þæt’ (that). Interestingly, macrons over vowels were originally used not to mark long vowels, as they are in modern editions, but to indicate stress or as abbreviations for a following ⟨m⟩ or ⟨n⟩.

Modern editions of Old English manuscripts introduce several conventions to aid contemporary readers. They employ modern forms of Latin letters, for example, ⟨g⟩ instead of the insular G, and ⟨s⟩ instead of the insular S and long S, among others that may differ considerably from the original insular script, such as ⟨e⟩, ⟨f⟩, and ⟨r⟩. Macrons are now consistently used to indicate long vowels, a distinction not typically made in the original manuscripts, though some older editions used an acute accent for consistency with Old Norse conventions. Furthermore, modern editors frequently distinguish between velar and palatal pronunciations of ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ by placing dots above the palatals, rendering them as ⟨ċ⟩ and ⟨ġ⟩. The letter wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ is usually replaced with ⟨w⟩, but ⟨æ⟩, ⟨ð⟩, and ⟨þ⟩ are generally retained, except when ⟨ð⟩ is replaced by ⟨þ⟩ for normalization. In contrast to the often erratic spelling of Modern English, Old English orthography was remarkably regular, featuring a largely predictable correspondence between letters and phonemes, with few silent letters. For instance, in the word ‘cniht’ (modern ‘knight’), both the ⟨c⟩ and ⟨h⟩ were pronounced (/knixt ~ kniçt/), unlike the silent ⟨k⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ in its modern counterpart (/naɪt/), showcasing a clear and direct phonetic representation.

8. Pivotal Literature: Unveiling Old English Masterpieces

The emergence of Old English literature marks a crucial period in the development of the English language, reflecting the cultural and spiritual life of the Anglo-Saxons. While poetry typically arose before prose in Old English literary tradition, a significant blossoming of literacy occurred after the Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England in the late 7th century. The oldest surviving work of Old English literature is the profoundly resonant “Cædmon’s Hymn,” a devotional poem composed between 658 and 680, though it was not committed to writing until the early 8th century. Before this, only a limited corpus of runic inscriptions from the 5th to 7th centuries existed, with the oldest coherent runic texts, such as those found on the Franks Casket, dating to the early 8th century. The 9th century saw a notable growth in Old English prose, largely inspired by Alfred the Great’s advocacy for education in English and his commissioning and participation in translating numerous works from Latin.

One of the most celebrated and pivotal works of Old English literature is the epic poem “Beowulf.” This masterpiece, penned by an anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet, exemplifies the sophisticated literary techniques of the era. A detail from the “Beowulf” manuscript famously shows the words “ofer hron rade,” which translates to “over the whale’s road (sea),” illustrating the use of a ‘kenning’. A kenning is a compound metaphorical expression, a stylistic device characteristic of Old English poetry, where a descriptive phrase is used in place of a simpler noun. Such vivid imagery and poetic structures are central to “Beowulf” and other heroic Old English verse.

Beyond epic poetry, Old English literature also encompassed a range of religious and administrative texts, which were vital for the spiritual and governmental life of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Among these significant religious works is an Old English version of “The Lord’s Prayer.” The translation and dissemination of fundamental Christian texts into the vernacular were integral to the Christianisation efforts and the establishment of a robust literary culture in English, making core tenets of faith accessible to a wider populace.

Another significant piece of literature, illustrating the practical and legal aspects of Old English writing, is the “Charter of Cnut.” Such charters were official documents, often detailing grants of land, legal decrees, or royal pronouncements, providing invaluable insights into the social, economic, and political structures of the time. The existence of these diverse literary forms—from heroic poetry to religious texts and legal documents—underscores the breadth and depth of Old English as a functional and expressive language in its own right, laying the groundwork for the rich literary traditions that would follow.

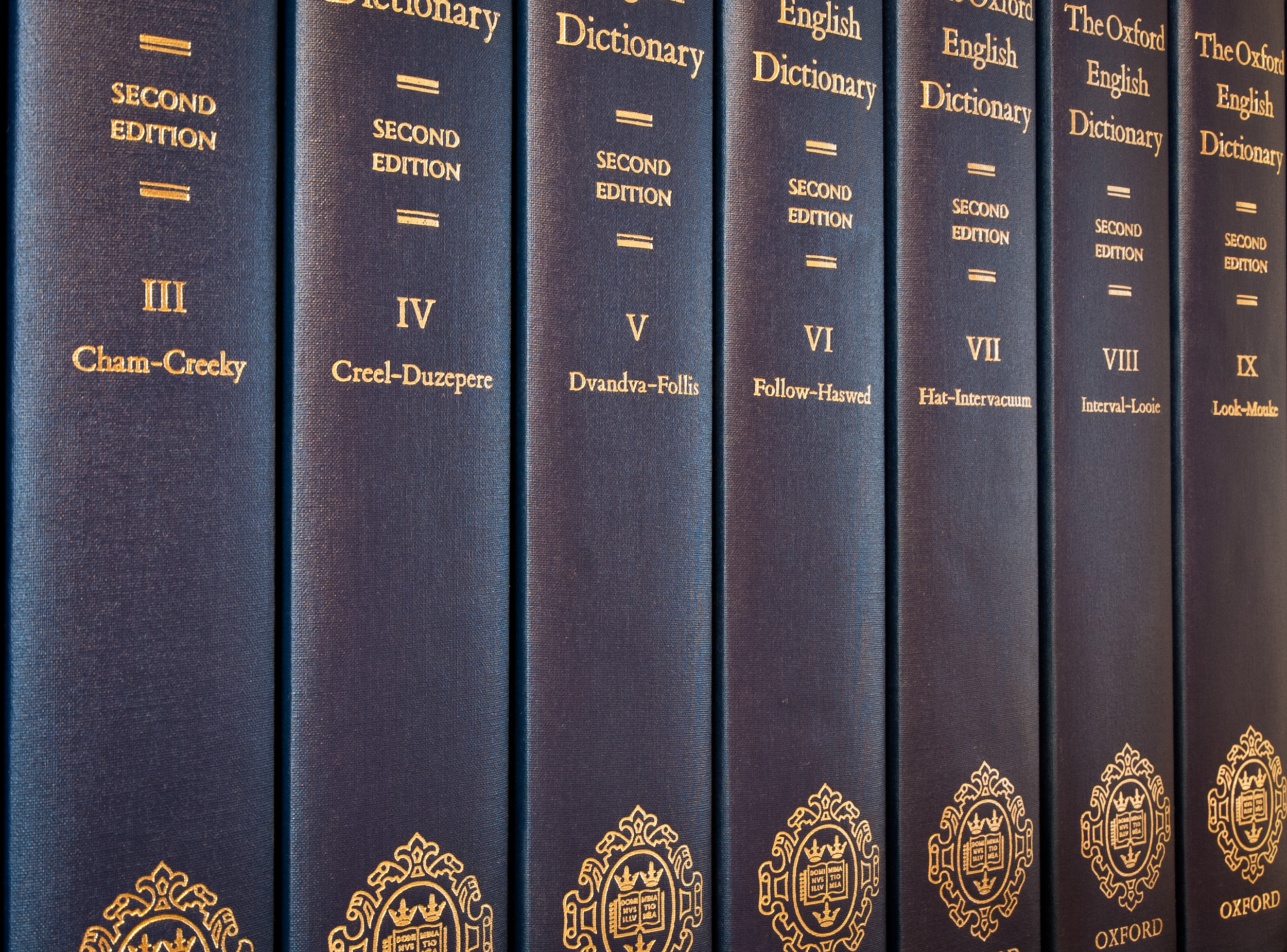

9. The Evolution of Old English Dictionaries

The journey of Old English scholarship has been greatly aided by the development and continuous refinement of its dictionaries, serving as indispensable tools for understanding this ancient language. The early history of Old English lexicons is a testament to the persistent academic effort to document and interpret a language that, for modern speakers, is largely incomprehensible without dedicated study. While detailed accounts of early dictionary creation are scarce, it is reasonable to infer that initial efforts likely involved the compilation of glossaries and word lists. These were crucial resources for Anglo-Saxon scribes and scholars, assisting them in the translation of Latin texts and in deciphering or explaining less common Old English words, effectively forming the foundational layer upon which more comprehensive lexicographical endeavors would later be built.

The transition from early glosses to modern, systematically compiled Old English dictionaries represents a significant scholarly evolution. Contemporary scholarship has produced extensive resources that are vital for students and researchers today. These modern dictionaries offer much more than simple definitions; they provide detailed etymologies, illustrate historical usage through contextually relevant examples drawn from the surviving corpus of Old English literature, and often delineate grammatical functions. They stand as the culmination of centuries of dedicated linguistic analysis, embodying the meticulous work of philologists who have painstakingly cataloged, cross-referenced, and interpreted the Old English lexicon.

The very existence and continuous evolution of Old English dictionaries highlight the enduring academic and cultural interest in this foundational language. They function as critical bridges, enabling modern scholars and enthusiasts to connect with the rich vocabulary and intricate nuances of a language that otherwise presents substantial barriers to comprehension. Without these systematic and comprehensive compilations of words, meanings, and historical contexts, much of the nuanced understanding of Old English texts, from epic poems to legal documents, would remain elusive. Thus, Old English dictionaries play an irreplaceable role in preserving and illuminating this crucial segment of our linguistic heritage, allowing its profound insights to be accessed and studied across generations.

Read more about: From ‘Bread-Kneader’ to Cultural Icon: The Jaw-Dropping Evolution of the Word ‘Lady’ You Won’t Believe!

10. The Profound and Continuing Modern Legacy of Old English

Although Old English might seem utterly foreign and largely incomprehensible to modern English speakers without dedicated study, its profound and continuing legacy is undeniable, forming the very bedrock of our linguistic heritage. It’s estimated that approximately 85% of Old English words are no longer in use, yet those that have survived constitute the fundamental elements of Modern English vocabulary, underscoring the deep roots of our everyday language. Understanding Old English is not merely an academic exercise; it’s an exploration into the very soul of the English language, uncovering the forces that shaped its structure, sound, and spirit, and appreciating the robust foundation upon which our present-day language was built.

The impact of Old English is particularly evident in the structural elements of Modern English, a consequence of centuries of linguistic evolution. Remnants of the Old English case system persist in Modern English pronouns, visible in distinctions such as “I/me/mine,” “she/her,” and “who/whom/whose.” Furthermore, the possessive ending “-‘s” in Modern English directly derives from the Old English masculine and neuter genitive ending “-es.” While the modern English plural ending “-(e)s” evolved from the Old English “-as,” it is important to remember that the Old English equivalent applied only to “strong” masculine nouns in the nominative and accusative cases, highlighting a significant simplification. Moreover, the compound verbal constructions found in Old English are the clear precursors to the compound tenses prevalent in Modern English. The distinction between strong verbs (which form the past tense by altering the root vowel) and weak verbs (which use a dental suffix), peculiar to the Germanic languages, also continues to characterize English grammar today.

The Old English period was pivotal in shaping not only English but also its closely related languages. By the 12th century, Old English had mostly developed into Middle English in England and Early Scots in Scotland. Crucially, while the Late West Saxon dialect formed the basis for the literary standard of late Old English, what would become the standard forms of Middle and Modern English are descended primarily from the Mercian dialect, rather than West Saxon. Similarly, Scots developed from the Northumbrian dialect. The regional variations evident in Old English dialects persisted into the Middle English period and, to some extent, are still discernible in modern English dialects, showcasing a continuity of regional speech patterns over more than a millennium.

Beyond vocabulary and grammar, Old English’s most profound external influence came from Old Norse, which Simeon Potter observed had a “no less far-reaching” impact on inflectional endings, “hastening that wearing away and leveling of grammatical forms.” This interaction between two closely related Germanic languages, where speakers could roughly understand each other, led to inflectional differences becoming “obscured and finally lost,” simplifying English grammar. This significant grammatical simplification, often attributed to Norse influence, is considered by many to be the greatest impact on the English language, demonstrating how Old English, though ancient, remains intrinsically linked to the living language we use today.

Read more about: Unpacking Excellence: The Definitive Guide to 2025’s Most Coveted Luxury SUVs and Their Unrivaled Safety Innovations

As we conclude our extensive exploration of Old English, it becomes abundantly clear that this ancient tongue is far more than a historical curiosity. It is the very foundation upon which the towering edifice of Modern English is built, a vibrant testament to centuries of linguistic adaptation, influence, and evolution. From its complex grammatical structures and evolving writing systems to its profound literary output and the scholarly efforts dedicated to its study, Old English offers an unparalleled window into the genesis of our language. Its echoes resonate in our everyday words, its structural legacy underpins our grammar, and its rich history continues to inform our understanding of who we are as speakers of English. The journey through Old English is a journey to the heart of our linguistic identity, revealing the deep, enduring connections between past and present, and ensuring that the voice of the Anglo-Saxons continues to speak through us, even today.