In the vibrant tapestry of American music, few figures shine as brightly and defiantly as Sylvester James Jr., known simply to the world as Sylvester. Born in the heart of Watts, Los Angeles, in 1947, his journey was a remarkable odyssey from the gospel choirs of his youth to becoming the undisputed ‘Queen of Disco’ – a title earned through sheer talent, an unforgettable falsetto, and an unwavering commitment to authentic self-expression. His life, marked by both dazzling highs and profound challenges, tells a powerful story of an artist who dared to live and create on his own terms, leaving an indelible mark on music, culture, and the fight for LGBTQ+ visibility.

Sylvester’s narrative is a compelling testament to the human spirit’s capacity for resilience and creativity. He navigated a world that often sought to confine him, defying societal norms and artistic conventions with a flamboyant and androgynous appearance that was ahead of its time. Beyond the glittering lights of the disco era, Sylvester was a deeply committed activist, using his platform to campaign tirelessly against the spread of HIV/AIDS, a battle that tragically claimed his own life in 1988. Yet, his voice, his vision, and his legacy continue to resonate, proving that some spirits, even when fate deals a harsh hand, refuse to be extinguished.

Join us as we embark on a journey through the extraordinary life of Sylvester, exploring the pivotal moments that shaped him, the creative collaborations that defined his sound, and the fearless spirit that cemented his place as an icon. From the streets of Los Angeles to the stages of San Francisco and beyond, this is the story of a trailblazer who not only found his own truth but helped countless others find theirs, too.

1. Childhood in Watts: Roots, Faith, and Early Challenges

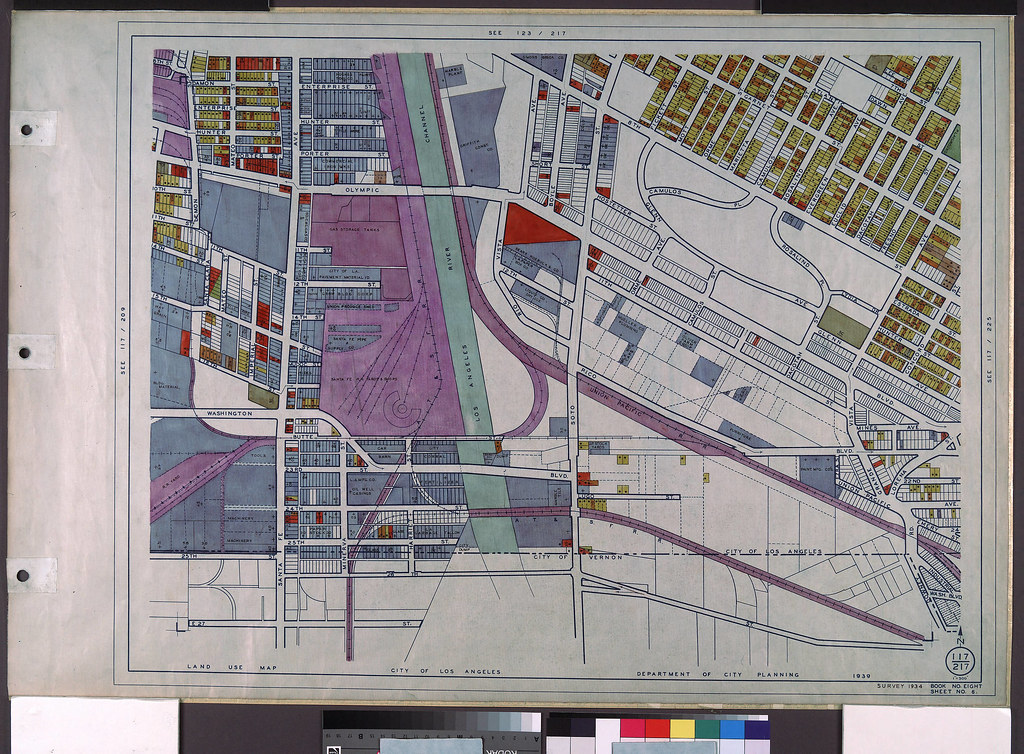

Sylvester James was born on September 6, 1947, in the Watts district of Los Angeles, into a middle-class African-American family. His early years were steeped in the traditions of his mother, Letha Weaver, a devout adherent of the Pentecostal denomination of Christianity. It was within the Palm Lane Church of God in Christ that young Sylvester first discovered his profound love for singing, actively participating in gospel performances from the tender age of three. This early exposure to the emotive power of gospel music would become a foundational element of his distinctive vocal style.

However, Sylvester’s childhood was also marked by a profound sense of being different. The women at his church described him as “feminine” and “pretty as he could be, just like his mother.” They recalled, “He wasn’t rough like the other boys. He was prim and proper. We were always hugging on him and kissing on him, because he was so cute.” Family members noted he was “his own kind of boy — ‘born funny'” – preferring the company of women and reading encyclopedias to the rough-and-tumble games of other boys. His mother, despite comments like “He act like a girl!” from other children, fiercely defended him, even embracing his joy in dressing up in her and his grandmother’s clothes, asserting he was “not a girl, just a different kind of boy, and a valued part of their family.”

Tragically, at the age of eight, Sylvester endured ual molestation by an adult at the church, an incident that led to his mother being informed by a doctor that her son was gay. Viewing homosexuality as a “perversion and a sin,” Letha struggled with this revelation. The news of Sylvester’s “homosexual activity” spread through the congregation, leading him to cease attendance at the age of 13 due to feeling unwelcome. This pivotal moment, coupled with a strained relationship with his mother and stepfather after his mother remarried, ultimately led Sylvester to leave home permanently, embarking on a path of self-discovery and resilience.

2. Finding Identity: The Disquotays and Self-Expression

Now homeless, Sylvester spent much of the next decade navigating life by staying with friends and relatives, most notably his beloved grandmother Julia. It was Julia who offered unwavering acceptance of his homouality, having had gay friends in the 1930s, providing a crucial haven for young Sylvester. During this period, he began to frequent local gay clubs, gradually building a vibrant community of friends from the local Black gay scene. These connections blossomed into a groundbreaking collective they called the Disquotays.

This daring group, composed of Black cross-dressers and transgender women, found profound joy and liberation in their shared identity. They were renowned for hosting lavish house parties, sometimes even (without permission) at the home of rhythm and blues singer Etta James. At these gatherings, they would transform themselves in female clothing and wigs, engaging in friendly competition to “outdo one another in appearance.” Biographer Joshua Gamson eloquently captured their spirit: “Dooni [Sylvester] and the Disquotays wandered the streets of South Central in the 1960s done up like women, and threw ferocious gay parties in neighborhoods whose strongest institutions were conservative Black churches. It’s tempting to see them as fearless and heroic, defiant sissies who were forerunners of Stonewall and sixties counterculture, part of the dawning of gay liberation and African-American civil rights organizing.”

Sylvester’s relationship with Lonnie Prince, a young and attractive man, marked a significant personal connection during the latter part of the 1960s, with friends describing them as “the It couple.” Despite the personal joy, this era was not without peril; cross-dressing carried the risk of arrest and prosecution in California, and Sylvester himself was arrested for shoplifting on several occasions. While the Civil Rights Movement was at its peak, Sylvester and his friends remained outside formal activism, instead joining in the widespread rioting and looting during the Watts riots, stealing wigs, hairspray, and lipstick – acts of defiant self-provision in a turbulent time. He remarkably graduated from Jordan High School in 1969, at 21, famously appearing in his graduation photograph in drag, adorned in a blue chiffon prom dress and beehive hairstyle. As the Disquotays eventually drifted apart, Sylvester, while always considering himself male, began to refine his aesthetic, moving towards a more androgynous look influenced by the hippie movement, blending male and female styles.

3. San Francisco Counterculture: The Cockettes and Solo Aspirations

The early 1970s marked a transformative period for Sylvester as he embraced the vibrant counterculture of San Francisco. After meeting Reggie Dunnigan at Los Angeles’ Whisky a Go Go bar, Sylvester was invited to join the “Chocolate Cockettes,” a subgroup within the avant-garde performance art drag troupe, The Cockettes. Founded by drag queen Hibiscus in 1970, The Cockettes were a radical collective that parodied popular culture, openly engaged with the Gay Liberation movement, and embodied the hippie ethos through communal living, free love, and the consumption of mind-altering substances.

San Francisco, with its reputation as a gay and counter-cultural haven, beckoned Sylvester, who had grown tired of Los Angeles following the disbandment of the Disquotays. Upon his arrival, his exceptional falsetto and piano skills immediately impressed The Cockettes, leading to an invitation to perform in their upcoming show, ‘Radio Rodeo.’ His early performances included singing ‘The Mickey Mouse Club’ theme song in a cowgirl skirt – a glimpse of the playful yet powerful artistry he would become known for. While he initially lived in their communal residence, the lack of privacy soon prompted him to move to a new house on Market Street with two fellow Cockettes.

Within the troupe, Sylvester cultivated a distinct presence. He stood out not only as one of the few African-American members but also for his preference for more “classier, more glamorous performances” compared to the group’s surrealist inclinations. Often given entire scenes to himself, regardless of their relevance to the show’s overall narrative, Sylvester began to build his own loyal following. Collaborating with piano player Peter Mintun, he showcased his deep interest in blues and jazz, expertly imitating his musical idols such as Billie Holiday and Josephine Baker. Adopting the pseudonym “Ruby Blue” and playfully describing himself as “Billie Holiday’s cousin once removed,” he actively explored Black musical heritage, even collecting “negrobilia” and, at times, playing up racial stereotypes on stage to subvert them. This period also saw Sylvester enter an open relationship with Michael Lyons, a young white man, and hold a non-legally recognized wedding in Golden Gate Park. His talent was further recognized with a one-man show, ‘Sylvester Sings,’ at the Palace Theater in 1971. Rolling Stone magazine, praising his performances, described him as “a beautiful Black androgyne who has a gospel sound with the heat and shimmer of Aretha.”

4. Struggles and Sound Shifts: The Hot Band Era

Sylvester’s burgeoning success with The Cockettes eventually led the troupe to New York City in November 1971. While the group largely indulged in the city’s avant-garde party scene, Sylvester remained focused, determined to perfect his act. When The Cockettes’ performance at the Anderson Theater was critically panned, Sylvester’s individual act stood out as a highlight, earning widespread praise. Realizing his potential as a solo artist, he famously declared on the second New York performance, “I apologize for this travesty that I’m associated with,” before announcing his departure from the group entirely on the seventh night. He was ready for a new chapter, one where his unique vision could truly take center stage.

Returning to San Francisco, Sylvester was offered the chance to record a demo album by Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, financed by A&M Records. For this project, he assembled a group of heteroual white males—Bobby Blood, Chris Mostert, James Q. Smith, Travis Fullerton, and Kerry Hatch—dubbing them the Hot Band. Despite recording a cover of The Carpenters’ hit “Superstar,” A&M found the work commercially unviable and declined its release. However, the Hot Band contributed two songs to ‘Lights Out San Francisco’ on the Blue Thumb label and gained local gigs, eventually opening for English glam rock star David Bowie at the Winterland Ballroom. Bowie, impressed by Sylvester’s shared preference for androgyny, famously commented that San Francisco didn’t need him because “They’ve got Sylvester.”

In early 1973, Sylvester and his Hot Band signed with Blue Thumb. On this label, they released their first album, originally titled ‘Scratch My Flower’ but issued as ‘Sylvester and his Hot Band.’ The sound shifted from blues to a more commercially appealing rock, with The Pointer Sisters even employed as backing singers. However, the album, primarily consisting of covers by artists like James Taylor and Neil Young, lacked “the fire and focus of the live shows,” as noted by one of Sylvester’s biographers, leading to poor sales. Music journalist Peter Shapiro observed that Sylvester’s “cottony falsetto was an uncomfortable match with guitars,” giving the albums an “unpleasantly astringent quality.” The band toured the United States, encountering threats of violence in conservative Southern states due to prevalent racist attitudes. A second album, ‘Bazaar,’ released in late 1973, also sold poorly, despite the Hot Band finding it more satisfying. Frustrated by the lack of commercial success and finding Sylvester difficult to work with, the Hot Band disbanded in late 1974, leading to the cancellation of his recording contract and the end of his relationship with Michael Lyons.

Read more about: Remember the 2000s? These 12 Iconic Moments and Cultural Revolutions Ruled the Decade—and Still Shape Our World!

5. Forging a New Path: The Two Tons O’ Fun and Solo Debut

The mid-1970s saw Sylvester grappling with renewed struggles. Without the Hot Band or a recording contract, he attempted to regroup with various backing singers, including the Four As and several Black drag queens. Despite performing at venues like Jewel’s Catch One, a predominantly Black gay dance club in Los Angeles, these new lineups failed to impress reviewers, and his backing singers soon departed. After a brief sojourn in England and a return to San Francisco, he continued to seek musical synergy, even performing at the 1975 Castro Street Fair, but consistent success remained elusive.

It was a critical turning point when Brent Thomson became his new manager. Thomson, recognizing the commercial landscape, advised Sylvester to shed his more flamboyant, androgynous image and adopt a more masculine presentation, candidly stating, “nobody is giving out recording contracts to drag queens.” Thomson held auditions for new backing singers, and it was here that Sylvester encountered the powerhouse vocalist Martha Wash, instantly captivated by her talent. Sylvester then asked if she knew another strong Black singer, leading Wash to introduce him to Izora Rhodes. These two phenomenal women, whom Sylvester affectionately called “the girls,” would soon become legendary as the Two Tons O’ Fun (later The Weather Girls) and develop a lifelong friendship and musical partnership with Sylvester. Biographer Joshua Gamson vividly captured their immediate chemistry: “Something clicked and sighed into place when Sylvester and the Tons got together – something that wasn’t there with the Hot Band white boys… They were women who got their own. They sounded right with Sylvester, and looked just right, one on either side of him. Plus, next to them, Sylvester, who had grown quite round, looked positively svelte.”

With Wash and Rhodes, along with bassist John Dunstan and keyboard player Dan Reich, Sylvester found his stride. Playing in gay bars like The Stud and The EndUp, the group secured a regular weekend gig at The Palms nightclub on Polk Street in September 1976. Their electrifying performances, a mix of covers and original compositions, caught the attention of Motown producer Harvey Fuqua, who subsequently signed Sylvester to a solo deal with Fantasy Records in 1977. This marked the release of his self-titled third album, ‘Sylvester,’ featuring a cover depicting him in more conventional male attire. The album, influenced by dance music, included his own compositions like “Never Too Late” and covers such as Ashford & Simpson’s “Over and Over.” Reviewers noted this shift towards a more conventional rhythm-and-blues image, designed for wider commercial appeal. “Over and Over” became a minor hit in the US and found greater success in Mexico and Europe, paving the way for tours in Louisiana and Mexico City.

6. The Disco Breakthrough: Step II and “Mighty Real”

Sylvester’s star was undoubtedly on the rise following the release of his solo album. His fame grew, leading to regular performances at The Elephant Walk gay bar in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood, a vibrant hub of the LGBT community. Here, he forged a friendship with Harvey Milk, the pioneering openly gay man elected to public office in California, even performing at Milk’s birthday party. This period also saw Sylvester make a cameo appearance in the film ‘The Rose,’ starring fellow gay icon Bette Midler, where he played one of the drag queens singing along to Bob Seger’s “Fire Down Below” in a memorable scene.

September 1978 heralded a seismic shift in Sylvester’s career with the release of his second solo album, ‘Step II.’ While initially unsure if the burgeoning genre of disco, closely associated with gay, Black, and Latino communities and dominated by Black female artists, was suitable for him, Sylvester recognized its immense commercial potential. For this groundbreaking album, he invited the innovative musician Patrick Cowley to join his studio band, captivated by Cowley’s masterful use of synthesizers. This collaboration blossomed into a close friendship and professional partnership, with Cowley becoming a key backup musician for Sylvester’s subsequent worldwide tours. Co-produced by Harvey Fuqua and released on Fantasy, ‘Step II’ unleashed two disco anthems that would define an era: “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real),” written by James Wirrick, and “Dance (Disco Heat),” penned by Eric Robinson.

Both singles were colossal commercial hits, soaring to the top of the American dance charts and making significant inroads into the US pop charts. The album itself achieved gold certification, with Rolling Stone magazine hailing it as being “as good as disco gets.” Music journalist Peter Shapiro, in his history of disco, declared “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” as Sylvester’s “greatest record,” “the cornerstone of gay disco,” and “an epochal record in disco history.” Shapiro eloquently noted how Sylvester’s work masterfully blended the “gospel/R&B tradition” with the “mechanical, piston-pumping beats” of disco, transcending both. He proclaimed, “Sylvester propelled his falsetto far above his natural range into the ether and rode machine rhythms that raced toward escape velocity, creating a new sonic lexicon powerful, camp, and otherworldly enough to articulate the exquisite bliss of disco’s dance floor utopia.” Sylvester’s magnetic performances and iconic voice quickly made him a sensation, leading to packed shows in London, a music video for “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real),” and appearances on major US television shows like ‘Dinah Shore,’ ‘American Bandstand,’ and ‘The Merv Griffin Show.’ He toured extensively, opening for stars like The Commodores and Chaka Khan, and performed alongside The O’Jays and War, earning numerous awards. Through his visible queer presence, alongside acts like the Village People, Sylvester solidified the connection between disco and homouality in the public imagination, inadvertently fueling the anti-disco sentiment that would emerge as the “Disco Sucks” movement, but undeniably cementing his place as a cultural icon.”

7. Navigating Post-Disco: Creative Control and New Collaborations (1979-1981)

After the dizzying heights of his breakthrough disco hits, Sylvester’s journey continued with *Stars*. This album signaled his evolving artistic vision, even as he expressed to the press a desire to move beyond the genre, calling *Stars* his first and likely last “completely disco album.” This period marked his assertion of greater creative control, a theme that would resonate throughout his later career, as the music industry’s tides began to turn against disco.

March 11, 1979, proved a momentous day. At a sold-out premiere of *Stars* at the San Francisco War Memorial Opera House, Mayor Dianne Feinstein’s aide awarded Sylvester the key to the city, proclaiming March 11 “Sylvester Day.” This public recognition cemented his status as a cherished figure in San Francisco’s vibrant community. The performance was recorded as the live album *Living Proof*, which, despite his high regard for it, saw poor sales. However, the single “Can’t Stop Dancing” became a hit in disco clubs.

Despite mainstream recognition, Sylvester remained deeply connected to the gay community. He headlined the 1979 Gay Freedom Day parade and performed at the London Gay Pride Festival, underscoring his authentic commitment. During this period, he met Jeanie Tracy, a powerful Black singer, who joined his backing vocalists, adding a new dynamic alongside Martha Wash and Izora Rhodes of the Two Tons O’ Fun. However, the Tons, encouraged by Harvey Fuqua, eventually pursued their own successful venture, gradually departing from Sylvester’s regular lineup. This separation, while evoking mixed feelings from Sylvester, saw him publicly express no ill will.

The early 1980s brought challenges, including an unfounded arrest in New York for coin robbery, from which he was exonerated after police admitted their mistake. This unsettling event coincided with the “Disco Sucks” movement, dramatically shifting the musical landscape. Returning to San Francisco, Sylvester navigated these changes with his 1980 Fantasy album, *Sell My Soul*. It marked a deliberate pivot from disco to soul-inspired dance tracks. However, working with unfamiliar musicians and without regular collaborators, the album received poor reviews and sales. His fifth and final Fantasy album, *Too Hot to Sleep*, further explored soul, ballads, and gospel, featuring Jeanie Tracy and Maurice “Mo” Long as the “C.O.G.I.C. Singers.” This album also featured his baritone voice, but it too struggled commercially, highlighting the difficulty of evolving creatively post-disco.

8. Reclaiming Independence: The Megatone Records Era (1982-1986)

Struggles with commercial success and creative direction led to Sylvester’s departure from Fantasy Records and a legal battle. Both he and the Two Tons O’ Fun suspected unpaid royalties, prompting a lawsuit in November 1982. The suit confirmed Fantasy withheld $218,112.50. However, former producer Harvey Fuqua paid only $20,000, leaving Sylvester deeply frustrated. He forbade friends from ever mentioning Fuqua’s name.

Facing industry indifference to a ‘disco’ artist, Sylvester prioritized creative control over chart success. As he noted in 1982, “there’s nothing worse than a fallen star” clinging to past fame. With friend Tim McKenna as his new manager, Sylvester signed with Megatone Records. This small, San Francisco company, founded by Patrick Cowley and Marty Blecman in 1981, served as a haven for dance-oriented music, primarily for the gay club scene.

His first Megatone album, *All I Need* (1982), reflected newfound artistic freedom. Primarily written by James Wirrick, it was dance-oriented with new wave influences, but Sylvester ensured his signature ballads were also included. The cover, depicting him in ancient Egyptian attire, visually represented this artistic rebirth.

This vibrant period saw the emergence of “Do Ya Wanna Funk,” an iconic Hi-NRG track co-written with Patrick Cowley. Released in July 1982, it topped US dance charts and made a global pop impact, a testament to their creative synergy. Tragically, Cowley was battling the recently identified HIV/AIDS virus (then “GRID”). While touring in London, Sylvester learned of Cowley’s death on November 12, 1982. He bravely informed the crowd onstage and performed “Do Ya Wanna Funk” as a powerful, poignant tribute.

9. An Emerging Crisis: HIV/AIDS Activism and Personal Loss

Patrick Cowley’s loss was a devastating introduction to the burgeoning HIV/AIDS epidemic. This crisis profoundly moved Sylvester, who channeled his grief into action. He understood his platform and visibility could make a difference, stepping up without hesitation.

Sylvester dedicated himself to helping those affected, volunteering at the Rita Rockett Lounge for patients at San Francisco General Hospital. This hands-on involvement showcased his unwavering compassion. He became a fervent activist, performing at benefit concerts to raise crucial funds and awareness, transforming his voice into a powerful instrument for advocacy and hope.

His music soon reflected this deepening awareness. In 1983, his second Megatone album, *Call Me*, continued to explore new musical territory but lacked commercial success. However, the single “Trouble in Paradise” held deep personal significance. Reaching the top 20 on US dance charts, Sylvester later described it as his “AIDS message to San Francisco,” a poignant declaration from a city grappling with a devastating health crisis.

10. A Lasting Partnership: Rick Cranmer and Public Declarations

Amidst his evolving career and the shadow of the AIDS epidemic, Sylvester found profound personal connection. In 1984, he began a loving relationship with architect Rick Cranmer. They moved into a new San Francisco apartment, which Sylvester uniquely decorated with Divine memorabilia. This domestic bliss provided a cherished haven amidst his professional demands and the ongoing health crisis.

Professionally, Sylvester pushed boundaries. His 1984 album, *M-1015*, embraced Hi-NRG, blending electro and rap for a frenetic sound. Though not written by him, the album, shaped by Kessie and Morey Goldstein, featured notable ually explicit lyrics like “How Do You Like Your Love” and “Sex,” showcasing fearless artistic expression. That year, he fulfilled a lifelong dream, collaborating with Aretha Franklin by providing backing vocals with Jeanie Tracy on *Who’s Zoomin’ Who?*, validating his vocal artistry.

His final album, *Mutual Attraction* (1986), produced by Megatone and licensed by Warner Bros., showcased his collaborative spirit. It featured diverse contributors and new tracks alongside covers of Stevie Wonder and George Gershwin. Reviews were mixed, but the single “Someone Like You” proved immensely successful, reaching number one on the Billboard dance charts, affirming his enduring appeal.

This period also marked a significant public moment on *The Late Show Starring Joan Rivers*. When Rivers mistakenly called him a “drag queen,” Sylvester, visibly annoyed, corrected her, declaring, “I’m Sylvester!” This powerful statement was immediately followed by a groundbreaking declaration: he publicly acknowledged his relationship with Rick Cranmer. This brave act was notable, as Cranmer’s family was largely unaware of their liaison or Rick’s uality, underscoring Sylvester’s unwavering commitment to living his truth authentically.

11. The Final Chapter: Illness, Activism, and Enduring Spirit

The shadow of HIV/AIDS tragically deepened in Sylvester’s life when, in 1985, his partner Rick Cranmer was diagnosed with HIV. With no known cure, Cranmer’s health rapidly deteriorated, leading to his heartbreaking death on September 7, 1987. Sylvester was devastated by this profound loss, a personal tragedy highlighting the epidemic’s devastating toll on his community.

Shortly after Cranmer’s passing, Sylvester received his own HIV diagnosis. Despite the immense burden, his resolve to fight for his community strengthened. He advocated tirelessly, using his voice and presence to raise awareness and funds for HIV/AIDS research and support services. This commitment became central to his identity, a testament to his indomitable spirit.

Even as his health declined, Sylvester continued to perform, his powerful voice and magnetic stage presence undimmed. At the 1988 Castro Street Fair, seated in a wheelchair, he captivated the crowd with “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real).” It was a poignant display of resilience, a superstar defiantly singing his anthem of joy and authenticity as his body weakened, serving as a powerful symbol of hope for a community in mourning.

Read more about: Ruth Paine’s Enduring Witness: A Deep Dive into the Life of a Key Figure in the Kennedy Assassination

12. The Indelible Legacy: Queen of Disco, Icon, and Philanthropist

On December 16, 1988, at 41, Sylvester James Jr. succumbed to HIV/AIDS complications. He left a void in music, but an enduring legacy. His final wish bequeathed all future royalties from his work to San Francisco-based HIV/AIDS charities. This philanthropic act ensured his artistry would perpetually fund the cause he championed, transforming his music into a beacon of hope.

Sylvester’s impact on music and culture is immeasurable. As the “Queen of Disco,” his flamboyant style, soaring falsetto, and groundbreaking hits defined an era. Beyond the dance floor, he solidified disco’s connection to homouality, creating spaces of liberation for LGBTQ+ individuals. His visible queer presence on mainstream stages, alongside acts like the Village People, paved the way for future generations to express themselves authentically.

Sylvester’s pioneering spirit garnered recognition years after his passing. In 2005, he was posthumously inducted into the Dance Music Hall of Fame, a fitting tribute to his revolutionary contributions. San Francisco, having embraced him fully, had already honored him with the key to the city and proclaimed March 11 “Sylvester Day,” cementing his place as a cherished local hero.

Read more about: Meghan Markle’s Royal Reckoning: Unpacking the Clash Between Disney Dreams and Dutiful Protocols

His compelling life story—a journey of resilience, self-discovery, and fearless authenticity—is immortalized through biographies, documentaries, and a musical. These tributes ensure the “Mighty Real” spirit of Sylvester continues to inspire. His voice, though silenced too soon, lives on, echoing his powerful message of joy, defiance, and unwavering self-love for generations to come.