Denmark, a Nordic country in Northern Europe, stands as the metropolis and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark, also known as the Danish Realm. This constitutionally unitary state extends its influence across the autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands and Greenland in the North Atlantic Ocean. Metropolitan Denmark, often called “continental Denmark” or “Denmark proper,” is composed of the northern Jutland peninsula and an extensive archipelago of 406 islands.

Positioned as the southernmost of the Scandinavian countries, Denmark lies southwest of Sweden, south of Norway, and shares a short border with Germany to its north. Its shores are embraced by the North Sea to the west and the Baltic Sea to the east. Within the broader Kingdom of Denmark, including the Faroe Islands and Greenland, there are approximately 1,400 islands greater than 100 square metres, with 443 named and 78 inhabited. As of May 1, 2025, Denmark’s population exceeds 6 million, with roughly 40% residing in Zealand, the largest and most populated island in Denmark proper. Copenhagen, the capital and largest city of the Danish Realm, is strategically located on Zealand, Amager, and Slotsholmen.

Denmark’s landscape is largely flat, comprising vast stretches of arable land. It is characterized by sandy coasts, low elevation, and a temperate climate, factors that have profoundly shaped its history and development. The nation exercises a hegemonic influence within the Danish Realm, devolving powers to its constituent entities for their internal affairs, as evidenced by home rule established in the Faroe Islands in 1948 and Greenland in 1979, with further autonomy in 2009. This structured governance underscores Denmark’s mature political framework.

The very name “Denmark” and its connection to the “Danes” has been a subject of continuous scholarly debate. Etymological dictionaries and handbooks typically trace “Dan” to a word signifying “flat land,” akin to the German “Tenne” or English “den” The element “mark” is widely believed to denote woodland or borderland, likely referring to the border forests in south Schleswig. The earliest recorded use of the word “Danmark” within Denmark itself is found on the Jelling stones, erected by Gorm the Old, considered Denmark’s first king around 955, and his son Harald Bluetooth around 965. The larger Jelling stone is famously referred to as the “baptismal certificate” of Denmark, though both stones contain the word in different grammatical forms, referring to the inhabitants as “Danes.”

Denmark’s rich history stretches back to ancient times, with the earliest archaeological finds dating from the Eem interglacial period, between 130,000 and 110,000 BC. Human habitation has been consistently present since approximately 12,500 BC, and evidence of agriculture appears around 3900 BC. The Nordic Bronze Age, from 1800 to 600 BC, left a legacy of burial mounds and remarkable artifacts such as lurs and the Sun Chariot, offering a glimpse into early Danish civilization. During the Pre-Roman Iron Age, native groups began migrating south, and the first tribal Danes arrived between the Pre-Roman and Germanic Iron Ages, specifically in the Roman Iron Age from AD 1 to 400.

Trade routes and relations flourished between Roman provinces and native tribes in Denmark during this period, evidenced by Roman coins found within Danish soil. Strong Celtic cultural influence is also discernible from this era across Denmark and much of Northwest Europe, exemplified by the discovery of the Gundestrup cauldron. The tribal Danes originated from the east Danish islands, notably Zealand, and Scania, now in Southern Sweden, speaking an early form of North Germanic. Historians suggest that before their arrival, Jutland and its nearby islands were primarily settled by tribal Jutes. Many Jutes famously migrated to Great Britain, reportedly as mercenaries, settling in areas like Kent and the Isle of Wight before being absorbed or ethnically cleansed by the invading Angles and Saxons. The remaining Jutish population in Jutland assimilated with the incoming Danes.

A brief mention of the Dani in Jordanes’ “Getica” is believed to be an early reference to the Danes, ancestors of modern Danes. Significant defensive structures known as Danevirke were constructed in phases from the 3rd century onwards, with the sheer scale of efforts in AD 737 indicating the probable emergence of a Danish king. A new runic alphabet emerged around the same time, and Ribe, Denmark’s oldest town, was founded about AD 700, marking a period of growing societal organization.

The Viking Age, spanning from the 8th to the 10th century, saw the wider Scandinavian population, known as Vikings by non-Scandinavians, make their mark. While their primary livelihoods were agriculture, fishing, and trade, their exceptional seafaring skills enabled them to travel extensively, reaching as far as Iceland, Greenland, and Canada. They engaged in trade across Europe, even reaching Constantinople, but were also renowned for raiding local settlements and establishing distant colonies. Danish Vikings notably focused their raiding activities on the eastern and southern British Isles and Western Europe.

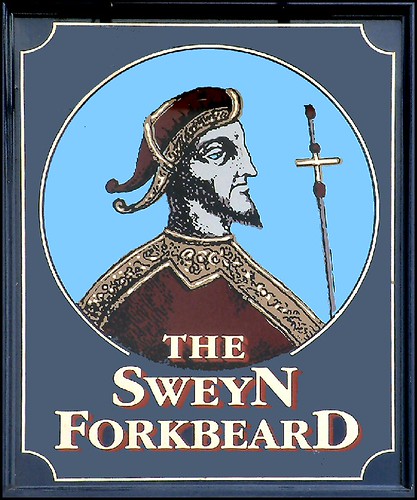

They established significant settlements in parts of England, famously known as the Danelaw, under King Sweyn Forkbeard in 1013, and in France, where Danes and Norwegians settled in what would become Normandy, pledging allegiance to Robert I of France with Rollo as their first ruler. Danish consolidation was largely complete by the late 8th century, with Frankish sources consistently referring to their rulers as kings. Under King Gudfred in 804, the Danish kingdom may have encompassed all the lands of Jutland, Scania, and the Danish islands, excluding Bornholm. The existing Danish monarchy traces its lineage to Gorm the Old, who established his reign in the early 10th century.

Christianization of the Danes, as evidenced by the Jelling stones, occurred around 965 under Harald Bluetooth, Gorm’s son. This conversion is widely believed to have been a politically motivated decision, aimed at preventing invasion by the Holy Roman Empire, a rising Christian power and crucial trading partner. To bolster defenses against this potential threat, Harald constructed six circular fortresses across Denmark, known as Trelleborg, and further extended the Danevirke. In the early 11th century, Canute the Great successfully united Denmark, England, and Norway for nearly three decades with a formidable Scandinavian army.

Throughout the High and Late Middle Ages, Denmark’s territorial scope also included Skåneland, comprising present-day Scania, Halland, and Blekinge in southern Sweden. Danish kings also ruled Danish Estonia and the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, much of which now forms the state of Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany. A significant shift occurred in 1397 when Denmark entered into the Kalmar Union with Norway and Sweden, united under Queen Margaret I. Although intended as a union of equals, Denmark, from the outset, emerged as the clear “senior” partner.

The next 125 years of Scandinavian history were largely dominated by the struggles surrounding this union, with Sweden repeatedly seceding and being reconquered. The issue was effectively resolved on June 17, 1523, when Swedish King Gustav Vasa conquered Stockholm. The Protestant Reformation swept across Scandinavia in the 1530s, leading to Denmark’s conversion to Lutheranism in 1536 following the Count’s Feud civil war. Later that same year, Denmark solidified a union with Norway, shaping its geopolitical future.

In the early modern period, after Sweden permanently broke away from the personal union, Denmark made several attempts to reassert control over its neighbor. King Christian IV’s attack on Sweden in the 1611–1613 Kalmar War failed to achieve its primary objective of forcing Sweden back into the union. While no territorial changes resulted, Sweden was compelled to pay a substantial war indemnity to Denmark, known as the Älvsborg ransom. Christian IV utilized these funds to establish new towns and fortresses, including Glückstadt, intended as a rival to Hamburg, and Christiania.

Inspired by the Dutch East India Company, King Christian IV founded a similar Danish company with ambitions of claiming Ceylon as a colony. However, this venture only managed to acquire Tranquebar on India’s Coromandel Coast. Denmark’s broader colonial aspirations involved a few key trading posts in Africa and India. While its trading posts in India were of limited note, Denmark played a significant role in the highly profitable Atlantic slave trade, operating through outposts such as Fort Christiansborg in Osu, Ghana, where approximately 1.5 million enslaved people were traded. Despite being sustained by trade and plantations, the Danish colonial empire ultimately stagnated due to a lack of resources.

Denmark’s involvement in the Thirty Years’ War saw Christian IV attempting to lead the Lutheran states in Germany, only to suffer a decisive defeat at the Battle of Lutter. This led to the Catholic army under Albrecht von Wallenstein invading, occupying, and pillaging Jutland, forcing Denmark’s withdrawal from the war. Remarkably, Denmark managed to avoid territorial concessions, yet King Gustavus Adolphus’ intervention in Germany signaled Sweden’s rising military power and Denmark’s declining regional influence. Swedish armies subsequently invaded Jutland in 1643 and claimed Scania in 1644.

The 1645 Treaty of Brømsebro saw Denmark cede Halland, Gotland, the last parts of Danish Estonia, and several provinces in Norway. Seizing an opportunity to reverse these losses, King Frederick III of Denmark declared war on Sweden in 1657, as Sweden was heavily engaged in the Second Northern War. This led to a devastating Danish defeat, with Swedish armies conquering Jutland and, following a daring march across the frozen Danish straits, occupying Funen and much of Zealand. The ensuing Peace of Roskilde in February 1658 forced Denmark to surrender Scania, Blekinge, Bohuslän, Trøndelag, and the island of Bornholm.

However, King Charles X Gustav of Sweden quickly regretted not having completely subdued Denmark and launched a second attack in August 1658. This assault saw him conquer most of the Danish islands and commence a two-year siege of Copenhagen. King Frederick III personally led the city’s defense, rallying its citizens, and successfully repelled the Swedish attacks. The siege concluded with Charles X Gustav’s death in 1660. In the subsequent peace settlement, Denmark managed to retain its independence and reclaim control of Trøndelag and Bornholm. Frederick III’s popularity surged after the war, which he leveraged to abolish the elective monarchy, establishing an absolute monarchy that persisted until 1848.

Denmark attempted unsuccessfully to regain control of Scania during the Scanian War from 1675 to 1679. Following the Great Northern War, from 1700 to 1721, Denmark regained control of parts of Schleswig and Holstein. The late 18th century marked a period of prosperity for Denmark due to its neutral status in contemporary wars, allowing it to trade with all belligerents. During the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark maintained trade with both France and the United Kingdom and joined the League of Armed Neutrality with Russia, Sweden, and Prussia. British fears of a Denmark-Norway alliance with France led to two attacks on Copenhagen in 1801 and 1807, resulting in the capture of most of the Dano-Norwegian navy and the outbreak of the Gunboat War. In 1807, much of Copenhagen, including Vor Frue Kirke, the main Danish cathedral, was destroyed by bombardments.

British control of the waterways between Denmark and Norway proved disastrous for the union’s economy, leading to Denmark–Norway’s bankruptcy in 1813. The union dissolved with the Treaty of Kiel in 1814, with the Danish monarchy irrevocably renouncing claims to the Kingdom of Norway in favor of the Swedish king. Denmark, however, retained Iceland, which remained under Danish monarchy until 1944, along with the Faroe Islands and Greenland, all of which had been governed by Norway for centuries. Beyond these Nordic territories, Denmark continued to rule over Danish India from 1620 to 1869, the Danish Gold Coast (Ghana) from 1658 to 1850, and the Danish West Indies from 1671 to 1917.

The 19th century saw the rise of a nascent Danish liberal and national movement, which gained significant momentum in the 1830s. Following the European Revolutions of 1848, Denmark peacefully transitioned into a constitutional monarchy on June 5, 1849. A new constitution was adopted, establishing a two-chamber parliament. However, this period was not without conflict, as Denmark faced war against both Prussia and the Austrian Empire in the Second Schleswig War, from February to October 1864. Denmark suffered defeat and was compelled to cede Schleswig and Holstein to Prussia.

This loss was the latest in a series of defeats and territorial cessions that had begun in the 17th century. Consequently, Denmark adopted a policy of neutrality in Europe. The second half of the 19th century witnessed the industrialization of Denmark. The nation’s first railways were constructed in the 1850s, and advancements in communications and overseas trade fostered industrial development despite Denmark’s limited natural resources. Trade unions began to emerge in the 1870s, reflecting changing social dynamics. A notable migration from rural areas to cities occurred, and Danish agriculture increasingly focused on the export of dairy and meat products, becoming a major agricultural exporter.

Denmark maintained its neutral stance during World War I. Following Germany’s defeat, the Versailles powers offered to return the region of Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark. However, fearing German irredentism, Denmark insisted on a plebiscite for the area’s return. The two Schleswig Plebiscites took place on February 10 and March 14, 1920. On July 10, 1920, Northern Schleswig was recovered by Denmark, adding approximately 163,600 inhabitants and 3,984 square kilometers to the country. The nation’s first social democratic government took office in 1924, signaling a shift in its political landscape.

In 1939, Denmark signed a 10-year nonaggression pact with Nazi Germany. Despite this, Germany invaded Denmark on April 9, 1940, leading to a swift surrender by the Danish government. The occupation, however, was characterized by a unique level of cooperation due to Germany’s reliance on Danish agricultural output, which supplied about 10% of the German army’s foodstuffs. This cooperative phase continued until 1943, when the Danish government refused further collaboration. In response, the Danish navy scuttled most of its ships, and many officers were sent to neutral Sweden, leading to the government’s collapse.

A significant act of resistance during the occupation was a rescue operation by the Danish resistance, which successfully evacuated several thousand Jews and their families to safety in Sweden before German forces could send them to death camps. While some Danes supported Nazism, volunteering to fight with Germany as part of the Frikorps Danmark, the broader resistance effort demonstrated a different national spirit. Iceland severed ties with Denmark and became an independent republic in 1944. Denmark itself was liberated after the war’s end in May 1945. In the post-war era, the Faroe Islands gained home rule in 1948, and Denmark became a founding member of NATO in 1949.

Denmark’s engagement with European integration began with its founding membership in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), often referred to as the Outer Seven in the 1960s, contrasting with the Inner Six of the European Economic Community (EEC). In 1973, along with Britain and Ireland, Denmark joined what is now the European Union after a public referendum. However, the Maastricht Treaty, which involved deeper European integration, was initially rejected by the Danish people in 1992, only to be accepted after a second referendum in 1993, which provided for four key opt-outs from EU policies. The Danes also rejected the euro as their national currency in a referendum in 2000.

Greenland achieved home rule in 1979 and was granted self-determination in 2009. Notably, neither the Faroe Islands nor Greenland are members of the European Union, with the Faroese declining membership in 1973 and Greenland in 1986, primarily due to concerns over fisheries policies. Constitutional changes in 1953 led to a single-chamber parliament elected by proportional representation, female accession to the Danish throne, and Greenland’s integration as a part of Denmark. The centre-left Social Democrats led a series of coalition governments for most of the latter half of the 20th century, laying the foundation for the Nordic welfare model. The Liberal Party and the Conservative People’s Party have also led center-right governments.

Geographically, Denmark is a distinctive landmass in Northern Europe. It consists of the northern part of the Jutland peninsula and an archipelago of 406 islands. Among these, Zealand stands as the largest island, hosting the capital Copenhagen, followed by the North Jutlandic Island, Funen, and Lolland. The island of Bornholm is situated about 150 km east of the main body of the country, in the Baltic Sea. Many of Denmark’s larger islands are interconnected by impressive bridges, such as the bridge-tunnel across the Øresund connecting Zealand with Sweden, the Great Belt Fixed Link connecting Funen with Zealand, and the Little Belt Bridge linking Jutland with Funen. Smaller islands rely on ferries or small aircraft for connectivity.

Denmark experiences a temperate climate, characterized by cool to cold winters, with a mean temperature of 1.5 °C in January, and mild summers, where the mean temperature in August reaches 17.2 °C. Since record-keeping began in 1874, the most extreme temperatures recorded have been 36.4 °C in 1975 and -31.2 °C in 1982. The country receives precipitation on an average of 179 days per year, totaling 765 millimeters annually, with autumn being the wettest season and spring the driest. Its geographical position between a continent and an ocean contributes to often unstable weather conditions. Due to Denmark’s northern latitude, there are significant seasonal variations in daylight, ranging from short winter days with sunrise around 8:45 am and sunset at 3:45 pm to long summer days with sunrise at 4:30 am and sunset at 10 pm, providing light throughout the night in mid-summer.

Ecologically, Denmark belongs to the Boreal Kingdom and is divided into two ecoregions: the Atlantic mixed forests and Baltic mixed forests. Historically, nearly all of Denmark’s primeval temperate forests have been destroyed or fragmented, primarily to facilitate agricultural expansion over millennia. This extensive deforestation led to the creation of vast heathlands and devastating sand drifts. Despite this historical impact, the country now possesses several larger second-growth woodlands, with a total of 12.9% of its land area currently forested. Norway spruce is the most widespread tree species, playing a significant role in Christmas tree production.

While Denmark’s Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score is notably low, ranking 171st globally out of 172 countries, it still supports diverse wildlife. Roe deer populations are growing in the countryside, and large-antlered red deer can be found in Jutland’s sparse woodlands. Smaller mammals such as polecats, hares, and hedgehogs also inhabit the nation. Approximately 400 bird species are found in Denmark, with about 160 of these breeding within the country’s borders. Marine ecosystems are robust, supporting healthy populations of harbor porpoises, growing numbers of pinnipeds, and occasional visits from whales, including blue whales and orcas. Cod, herring, and plaice are abundant culinary fish in Danish waters, forming the foundation of a substantial fishing industry.

Denmark has historically adopted a progressive stance on environmental preservation, establishing a Ministry of Environment in 1971 and becoming the first country globally to implement an environmental law in 1973. While land and water pollution remain significant environmental concerns, much of the nation’s household and industrial waste is increasingly filtered and often recycled. Denmark is a signatory to the Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, its national ecological footprint is 8.26 global hectares per person, which is notably high compared to the world average, potentially influenced by its substantial meat production and the economic scale of its meat and dairy industries. Despite these emissions, Denmark has consistently topped the list of the Climate Change Performance Index since 2020 due to its effective climate protection policies. In 2021, Denmark co-launched the “Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance” with Costa Rica, aiming to halt the use of fossil fuels, and the Danish government ceased issuing new licenses for oil and gas extraction in December 2020. The territories of Greenland and the Faroe Islands collectively catch approximately 650 whales per year, with Greenland’s quotas determined by the advice of the International Whaling Commission, which holds quota decision-making powers.

Politics in Denmark operate within a framework established by the Constitution of Denmark. First written in 1849, this document defines Denmark as a sovereign state structured as a constitutional monarchy with a representative unicameral parliamentary system. Officially, the monarch retains executive power and presides over the Council of State. In practice, however, the monarch’s duties are strictly representative and ceremonial, including the formal appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister and other government ministers. The monarch is sacrosanct and not answerable for their actions. Hereditary monarch King Frederik X has been the head of state since January 14, 2024.

The Danish parliament, known as the Folketing, is unicameral and serves as the legislature for the Kingdom of Denmark, enacting laws applicable in Denmark and, with variations, in Greenland and the Faroe Islands. The Folketing is also responsible for adopting state budgets, approving state accounts, appointing and overseeing the Government, and participating in international cooperation. Both the Government and individual members of parliament can initiate bills. All passed bills must be presented to the Council of State for Royal Assent within thirty days to become law. Denmark operates as a representative democracy with universal suffrage. Membership in the Folketing is based on proportional representation of political parties, with a 2% electoral threshold. Denmark elects 175 members to the Folketing, with Greenland and the Faroe Islands each electing an additional two, totaling 179 members. Parliamentary elections are held at least every four years, though the prime minister holds the power to request the monarch to call an election earlier. The Folketing can compel a single minister or an entire government to resign through a vote of no confidence.

The Government of Denmark functions as a cabinet government, where executive authority is formally exercised on behalf of the monarch by the prime minister and other cabinet ministers, who lead specific ministries. As the executive branch, the Cabinet is tasked with proposing bills and a budget, executing laws, and guiding Denmark’s foreign and internal policies. Typically, the monarch requests the individual most likely to command a majority’s confidence in the Folketing to become prime minister, often the leader of the largest political party or a coalition of parties. Single parties rarely hold enough seats to form a cabinet independently, meaning Denmark is frequently governed by coalition governments, often minority governments reliant on support from non-government parties. Following the November 2022 Danish general election, incumbent Prime Minister and Social Democratic leader Mette Frederiksen formed the current Frederiksen II Cabinet in December 2022, a coalition government including the previously leading opposition party Venstre and the recently established Moderate party.

Denmark operates under a civil law system, incorporating some elements of Germanic law. Similar to Norway and Sweden, Denmark has not developed a case-law system akin to England and the United States, nor comprehensive codes like those found in France and Germany; much of its law is customary. The judicial system is divided into courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts overseeing litigation between individuals and public administration. Articles sixty-two and sixty-four of the Constitution ensure judicial independence from both government and Parliament, stipulating that judges must be guided solely by the law, including acts, statutes, and practice. While the Kingdom of Denmark does not have a single unified judicial system, with Denmark, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands each having distinct systems, decisions from the highest courts in Greenland and the Faroe Islands can be appealed to the Danish High Courts. The Danish Supreme Court serves as the highest civil and criminal court responsible for justice administration across the Kingdom. In 2023, the World Justice Project ranked Denmark first on their rule of law index.

The Kingdom of Denmark is a unitary state, encompassing metropolitan Denmark along with the two autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands and Greenland in the North Atlantic Ocean. These territories have been integrated parts of the Danish Realm since the 18th century. However, recognizing their distinct historical and cultural identities, these parts of the Realm have been granted extensive political powers, assuming legislative and administrative responsibility in numerous fields. Home rule was granted to the Faroe Islands in 1948, allowing them significant self-governance.

Denmark stands today as a developed country with an advanced high-income economy, providing its citizens with a high standard of living and robust social welfare policies. Danish culture and society are broadly progressive, egalitarian, and socially liberal, famously being the first country to legally recognize same-sex partnerships. It is a founding member of key international organizations, including NATO, the Nordic Council, the OECD, the OSCE, the Council of Europe, and the United Nations, and participates in the Schengen Area. The nation maintains deep political, cultural, and linguistic ties with its Scandinavian neighbors. The Danish political system, characterized by its emphasis on broad consensus, is cited by American political scientist Francis Fukuyama as a reference point for near-perfect governance, with his phrase “getting to Denmark” referring to the country’s status as a “global model for stable social and political institutions.

In essence, Denmark’s journey, from its ancient origins and Viking might to its contemporary role as a beacon of stable governance and progressive societal values, is a testament to its enduring adaptability and vision. This island-rich Nordic nation, shaped by a complex history of unity, conflict, and innovation, has consistently evolved, demonstrating a remarkable capacity for social cohesion and environmental stewardship. Its commitment to comprehensive welfare policies, judicial independence, and a consultative political system underscores its reputation as a global exemplar, embodying a balanced approach to prosperity and social equity. Denmark continues to inspire as a testament to what a nation can achieve through deliberate progress and a steadfast commitment to its people and planet.