Florida, a prominent state in the Southeastern region of the United States, stands as a unique nexus of historical depth, ecological diversity, and significant demographic growth. Its distinctive peninsular geography, nestled between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, has profoundly shaped its development, culture, and economic trajectory. This exploration delves into the foundational elements that define Florida, from its ancient origins and early European encounters to its evolving socio-economic landscape.

Often recognized globally for its vibrant tourist attractions and inviting climate, Florida’s narrative is far richer than its popular image suggests. The state’s history is marked by complex interactions among various indigenous peoples, European powers, and waves of migrants, each leaving an indelible mark. Understanding these multifaceted layers provides a clearer picture of Florida’s identity as a pivotal U.S. state.

This first section of our comprehensive review will illuminate Florida’s core attributes. We will begin by examining its defining geographical features and population dynamics, before delving into its robust economic sectors. Subsequently, we will trace the significant historical epochs that shaped Florida, from its initial habitation by Native American tribes and the advent of European explorers to the critical periods of Spanish and British colonial rule.

1. **Florida’s Distinct Geographic Identity**

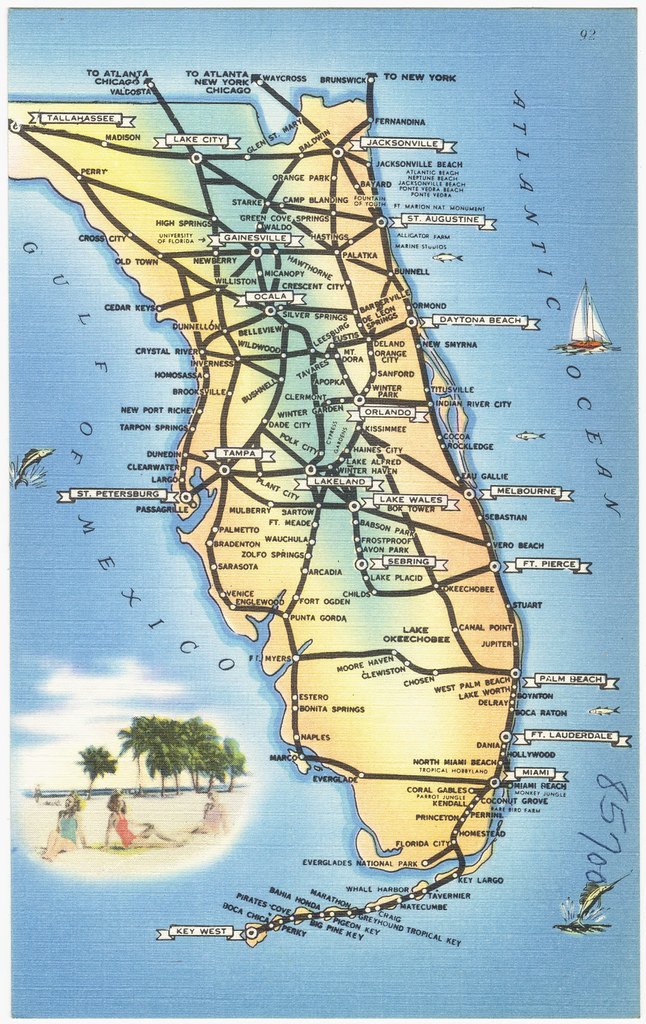

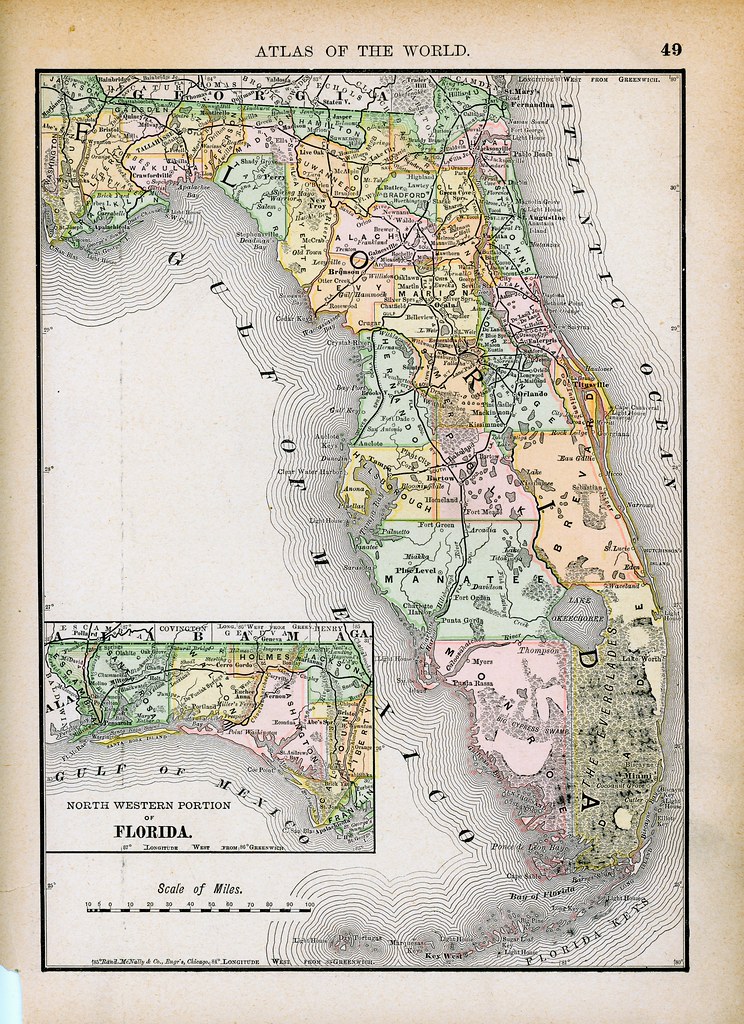

Florida’s physical geography is characterized by its expansive peninsula, which strategically extends between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. This unique positioning makes it the sole state that borders both major bodies of water, contributing to its extensive coastline, which spans approximately 1,350 miles, not including its numerous barrier islands. The state also extends northwest into a panhandle, sharing its northern borders with Georgia and Alabama, and its western edge, at the end of the panhandle, with Alabama.

Much of Florida is recognized for its low-lying, flat terrain, with significant portions lying at or near sea level. While the state is generally considered the flattest in the United States, variations in elevation do exist. Central and North Florida, particularly areas more than 25 miles from the coastline, feature rolling hills with elevations typically ranging from 100 to 250 feet. Notable high points include Britton Hill, at 345 feet above mean sea level—the lowest high point of any U.S. state—and Sugarloaf Mountain in Lake County, which stands as the highest point in peninsular Florida at 312 feet.

Beyond its landforms, Florida’s hydrological features are equally distinctive. Lake Okeechobee, the state’s largest lake, holds the distinction of being the second-largest natural freshwater lake contained entirely within the contiguous 48 states, surpassed only by Lake Michigan. The St. Johns River, stretching 310 miles, is the longest river within Florida, notable for its minimal elevation drop of less than 30 feet from its headwaters in South Florida to its mouth in Jacksonville.

2. **Demographics and Major Urban Centers**

Florida has undergone substantial demographic and economic expansion since the mid-20th century, establishing itself as a major population hub in the United States. With a population exceeding 23 million, it ranks as the third-most populous state nationally and seventh in population density as of 2020. This growth is not merely an increase in numbers but a transformation of its urban landscape and cultural fabric.

The state’s population is concentrated in several prominent metropolitan areas, each contributing to Florida’s economic and cultural dynamism. The Miami metropolitan area, anchored by the cities of Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach, is the largest in the state, boasting a population of 6.138 million. Jacksonville stands as the most populous single city within Florida, serving as a significant northern hub.

Other major population centers include Tampa Bay, a critical economic and cultural region on the Gulf Coast; Orlando, renowned globally for its amusement parks and tourism industry; and Cape Coral. Tallahassee serves as the state capital, playing a vital role in governance and education. The continuous influx of both domestic and international migrants further underscores Florida’s appeal as a destination for retirees, seasonal vacationers, and those seeking new opportunities.

3. **Economic Pillars and Global Appeal**

Florida’s economy is robust and diversified, recognized as the fourth largest of any U.S. state and ranking fifteenth-largest globally, with a gross state product (GSP) of $1.647 trillion. This economic prowess is built upon several key sectors that leverage the state’s natural advantages and strategic location. Tourism and hospitality remain cornerstone industries, drawing tens of millions of visitors annually.

The state is world-renowned for its extensive beach resorts, iconic amusement parks such as Walt Disney World, and historical sites like the Kennedy Space Center. Its warm and sunny climate, coupled with abundant nautical recreation opportunities, further enhances its appeal as a premier destination. This sustained allure is evident in the continuous flow of visitors and new residents.

Beyond tourism, agriculture plays a significant role, contributing to Florida’s economic output with products such as citrus fruits, strawberries, nuts, sugarcane, and cattle. Real estate development is another vital sector, fueled by the steady stream of domestic and international migrants, retirees, and seasonal vacationers who choose to reside or invest in Florida. The transportation sector, critical for facilitating both trade and travel, also contributes substantially to the state’s robust economic framework.

4. **Early Inhabitants and European Contact**

Florida’s rich history extends far beyond European arrival, with evidence indicating human habitation by Paleo-Indians for at least 14,000 years. By the 16th century, the period for which historical records begin to emerge, the region was home to several major Native American groups. These included the Apalachee of the Florida Panhandle, the Timucua inhabiting northern and central Florida, the Ais along the central Atlantic coast, the Mayaimi near Lake Okeechobee, the Tequesta in southeastern Florida, and the Calusa of southwest Florida. These tribes developed distinct cultures and communities across the diverse Floridian landscape.

The European presence in Florida commenced in 1513 when Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León made the first known European landfall on the peninsula. He named the region “La Florida,” or “land of flowers,” a designation given in recognition of the verdant landscape and its timing during the Easter season, which Spaniards referred to as Pascua Florida, or “Festival of Flowers.” This initial contact marked the beginning of centuries of European influence on the land and its indigenous inhabitants.

Ponce de León and his expedition came ashore on April 3, 1513, with the dual objectives of gathering information and formally claiming the new territory. While a popular narrative suggests he sought the legendary Fountain of Youth, this story is largely apocryphal, appearing long after his death. His voyage, nonetheless, opened a new chapter for the continent, setting the stage for subsequent European explorations and attempts at permanent settlement.

5. **The Dawn of Permanent European Settlement**

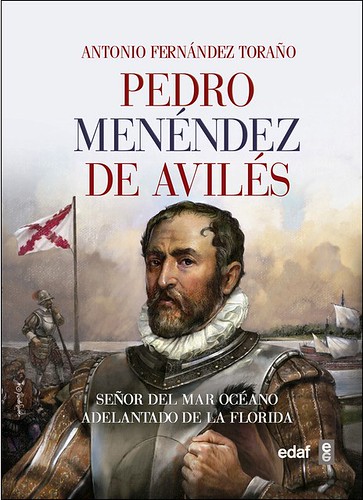

Florida holds the unique distinction of being the first area in the continental United States to be permanently settled by Europeans. This significant historical milestone occurred with the establishment of St. Augustine (San Agustín) in 1565, under the leadership of Admiral and Governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. This settlement evolved into the oldest continuously occupied European settlement in the continental U.S., laying the groundwork for the first generation of Floridanos and the early governance of Florida.

The establishment of St. Augustine was not merely a military or administrative achievement; it also marked significant social developments. In 1565, the marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian, took place in St. Augustine. This event is historically recognized as the first recorded Christian marriage in the continental United States, highlighting the early multi-ethnic character of the nascent colony.

As the settlement grew, the Spanish fostered a unique social environment. Some Floridanos engaged in marriages or unions with Pensacola, Creek, or African women, both enslaved and free, leading to the emergence of a mixed-race population comprising mestizos and mulattoes. This dynamic demographic structure was further shaped by Spain’s policy of encouraging enslaved individuals from the Thirteen Colonies to seek refuge in Florida, promising them freedom in exchange for their conversion to Catholicism and baptism, thus creating communities of free blacks.

6. **Spanish Rule and the Fight for Freedom**

Under Spanish rule, Florida became a sanctuary for enslaved people seeking liberty, a policy formalized by King Charles II of Spain. He issued a royal proclamation granting freedom to all enslaved individuals who fled to Florida, provided they accepted conversion to Catholicism and baptism. Many of these individuals settled around St. Augustine, while others found refuge in Pensacola. This policy profoundly influenced the demographic and social landscape of Spanish Florida.

An early testament to the integration of free blacks into Florida’s defense structures is the all-black militia unit mustered in St. Augustine as early as 1683. This unit played a role in defending Florida, showcasing the military contributions of its diverse population. The strategic importance of Florida to Spain was underscored by the construction of fortifications like the Castillo de San Marcos in 1672 and Fort Matanzas in 1742, built to protect the capital city from repeated attacks by English colonists and buccaneers. These defenses were crucial for maintaining Spain’s position in the defense of the Captaincy General of Cuba and the Spanish West Indies.

A landmark development occurred in 1738 when Governor Manuel de Montiano established Fort Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose near St. Augustine. This fortified town was explicitly created for escaped enslaved individuals, to whom Montiano granted citizenship and freedom in exchange for their service in the Florida militia. Fort Mose became North America’s first legally sanctioned free black settlement, representing a beacon of hope and a significant defiance of the institution of slavery in neighboring colonies.

7. **The British Interlude and Legal Foundations**

Florida’s complex colonial history saw a pivotal shift in 1763, when Spain ceded the territory to the Kingdom of Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Paris, which concluded the Seven Years’ War. This exchange granted Spain control of Havana, Cuba, which had been captured by the British during the conflict. The transfer of sovereignty led to a significant exodus of the existing Florida population, including a large portion of the remaining Indigenous inhabitants, who relocated to Cuba.

Upon gaining control, the British government undertook efforts to develop the newly acquired territory. They divided the Florida provinces into East Florida and West Florida, a demarcation that the Spanish Crown would later retain upon regaining the territory. To encourage settlement, Britain offered land grants to officers and soldiers who had participated in the French and Indian War. Reports promoting Florida’s natural wealth were published in England, attracting settlers described as “energetic and of good character” primarily from South Carolina, Georgia, England, and Bermuda. This marked the establishment of the first permanent English-speaking population in certain counties.

During this period, the British introduced significant advancements and institutional changes. They constructed improved public roads, including the King’s Road connecting St. Augustine to Georgia, which crossed the St. Johns River at “Cow Ford,” now downtown Jacksonville. Furthermore, they introduced the cultivation of sugar cane, indigo, and fruits, alongside lumber export. Crucially, British governors were instructed to establish general assemblies and courts, leading to the initial introduction of the English-derived legal system still present in Florida today, including trial by jury, habeas corpus, and county-based governance. Despite these developments, Florida remained a Loyalist stronghold throughout the American Revolution, sending no representatives to draft the Declaration of Independence. Spain ultimately regained both East and West Florida after Britain’s defeat in the Revolutionary War and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles in 1783, maintaining these provincial divisions until 1821.

Having established Florida’s foundational characteristics and early colonial history, we now turn our attention to the pivotal moments that shaped its modern identity. This next phase of our journey will encompass Florida’s complex path to statehood, the profound impact of national conflicts like the American Civil War, and the dramatic socio-economic transformations that unfolded throughout the 20th century. We will also explore the state’s defining climate and natural phenomena, concluding with a glimpse into its rich and diverse wildlife.

8. **From Territory to Statehood: The Seminole Wars and Beyond**

The early 19th century witnessed a significant influx of American settlers, primarily of English and Scots-Irish descent, into northern Florida from the backwoods of Georgia and South Carolina. These migrants, blending with the British settlers who had remained after 1783, formed the progenitors of the population known as Florida Crackers, establishing a permanent foothold that would gradually challenge Spanish governance. This period was marked by territorial disputes, including a rebellion in 1810 that briefly saw the establishment of the so-called Free and Independent Republic of West Florida, and President James Madison’s subsequent annexation of parts of West Florida into the U.S. Territory of Orleans.

Further compounding the territorial complexities were the Seminole Wars, a series of protracted conflicts central to Florida’s path to statehood. Early skirmishes near the border with Georgia led to the First Seminole War (1816–1819), with American military incursions led by Andrew Jackson effectively asserting U.S. control over East Florida. This military leverage, combined with Spain’s diminished capacity to govern the territory following the Peninsular War, culminated in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, through which Spain ceded Florida to the United States. The U.S. took possession in 1821, with Andrew Jackson briefly serving as military commissioner and governor.

Upon consolidation of East and West Florida into the Florida Territory in 1822, pressure mounted to remove Native American populations, particularly the Seminoles. The Treaty of Moultrie Creek (1823) confined them to a large reservation in the interior of the peninsula, but the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832) called for their relocation to Indian Territory. Resistance to these policies led to the devastating Second Seminole War (1835–1842), resulting in the forced removal of most Seminoles and Black Seminoles, though a few hundred remained in the Everglades, never surrendering. Florida officially became the 27th U.S. state on March 3, 1845, admitted as a slave state, and the Third Seminole War (1855–1858) completed the forced removal of many remaining Seminoles. Meanwhile, South Florida saw later settlement by Bahamian treasure hunters, Seminoles, and runaway slaves, with Miami seeing its first significant growth after the Second Seminole War.

9. **The Civil War and Reconstruction Era**

By 1860, Florida’s demographic landscape was significantly shaped by the institution of slavery, particularly in its burgeoning cotton plantations in the north. The state’s population stood at 140,424 people, with an alarming 44% classified as enslaved, and fewer than 1,000 free African Americans. This reliance on slave labor heavily influenced Florida’s political trajectory, leading to a pivotal decision on January 10, 1861, when nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession. This act declared Florida a “sovereign and independent nation,” making it one of the original founding members of the Confederate States of America.

Throughout the American Civil War, Florida’s direct military contribution to the Confederacy was relatively modest, with its approximately 15,000 troops generally dispatched to other theaters of conflict. However, the state played a crucial strategic role in providing vital resources. Florida supplied significant quantities of salt and, more importantly, beef to sustain the Confederate armies, especially after 1864 when the Confederacy lost control of the Mississippi River, thereby cutting off access to Texas beef. The state did witness a few significant engagements, notably the Battle of Olustee on February 20, 1864, and the Battle of Natural Bridge on March 6, 1865, both of which resulted in Confederate victories within its borders.

The war concluded in 1865, ushering in the complex Reconstruction era. Florida’s congressional representation was forcibly restored on June 25, 1868, under federal military commanders and unelected government officials. Following the end of Reconstruction in 1876, white Democrats regained political control, enacting a new constitution in 1885 and subsequent statutes by 1889 that effectively disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Amidst these political shifts, the late 19th century saw a crucial development in the state’s infrastructure with the expansion of railroads, connecting Pensacola and the Panhandle to the rest of the state, and extending services to key coastal areas like Tampa, West Palm Beach, and Miami, laying the groundwork for future growth.

10. **Twentieth-Century Socio-Economic Transformations**

The early 20th century saw Florida’s economy still heavily reliant on agriculture, with products such as citrus fruits, strawberries, nuts, sugarcane, and cattle forming its backbone. However, this sector faced significant challenges, including the devastating impact of the boll weevil on cotton crops. Despite its agricultural output, Florida remained the least populous state in the southern United States in 1900, with a population of only 528,542, and notably, African Americans still constituted nearly 44% of this total, a proportion unchanged since before the Civil War.

This period also marked the Great Migration, where approximately 40,000 black Floridians, roughly one-fifth of their 1900 population, departed the state. They sought refuge from lynchings and pervasive racial violence, migrating to the North and West for better opportunities. Within Florida, the struggle for civil rights gained momentum in the 1950s and 1960s, evidenced by significant protests such as the Florida A&M University bus boycott in Tallahassee (1956–1957) which led to desegregation, student sit-ins against segregated lunch counters in 1960, and a pivotal incident at a St. Augustine motel pool in 1964, which is credited with influencing the passage of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act. Disenfranchisement for most African Americans in the state persisted until federal legislation in 1965 enforced protection of their constitutional suffrage.

Economic prosperity returned in the 1920s, significantly stimulating tourism and leading to the extensive development of hotels and resort communities. This period was characterized by the notorious Florida land boom of the 1920s, a brief but intense period of real estate speculation and development. However, this boom was abruptly halted by devastating hurricanes in 1926 and 1928, followed by the onset of the Great Depression. Florida’s economy did not fully recover until the military buildup for World War II provided a much-needed boost. Although described as “still very largely an empty State” in 1939, the post-1945 era saw a sharp increase in population, driven by the growing availability of air conditioning, the state’s inviting climate, and a relatively low cost of living, attracting migrants from the Rust Belt and the Northeast.

11. **Contemporary Demographics and Social Dynamics**

Florida’s population growth has surged into the 21st century, continuing the trends established in the latter half of the 20th century. According to the 2010 census, the state’s population exceeded 18 million, cementing its status as the most populous state in the southeastern United States and the third-most populous in the nation. This expansion has been remarkably widespread, with cities across the entire state experiencing continuous population growth. By 2019, Florida distinguished itself as the recipient of the largest number of out-of-state movers in the country, underscoring its enduring appeal as a destination for new residents.

Beyond domestic migration, Florida has long been a significant destination for international migrants, a trend vividly exemplified by the arrival of many refugees from Cuba in the 1960s. Fleeing Fidel Castro’s communist regime, these newcomers primarily arrived at the Freedom Tower in Miami, a facility utilized by the federal government to process, document, and provide essential medical and dental services for them. Consequently, the Freedom Tower earned the poignant nickname “Ellis Island of the South,” symbolizing its critical role in welcoming new populations. In more recent decades, the flow of migrants has increasingly been drawn by the burgeoning job opportunities within Florida’s continually developing economy.

The 21st century in Florida has also been marked by several tragic high-profile mass shootings that have garnered national attention and instigated calls for policy changes. In June 2016, a gunman killed 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando, an incident that stands as the deadliest in the history of violence against LGBT people in the United States, and at the time, the deadliest terrorist attack in the U.S. since September 11, 2001. Just two years later, in February 2018, 17 lives were lost in a school shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, leading to new gun control regulations at both the state and federal levels. More recently, on June 24, 2021, a devastating condominium collapse in Surfside, near Miami, claimed the lives of at least 97 people, tying it as the third-deadliest structural engineering failure in U.S. history.

12. **Florida’s Diverse Climates and Weather Patterns**

Florida’s climate is notably moderated by its unique geography, with no part of the state being far from the ocean’s influence. North of Lake Okeechobee, the prevailing climate is humid subtropical, characterized by warm, humid summers and mild winters. South of the lake, including the iconic Florida Keys, the climate transitions to a true tropical classification, making Florida the only U.S. state besides Hawaii to boast a tropical climate, and the sole continental state with a living coral reef. Its overall warmth is reflected in its status as the warmest state in the U.S., with an average daily temperature of 70.7 °F (21.5 °C).

Throughout the year, temperatures vary across the state, though extreme highs are rare. Mean high temperatures in late July typically range in the low 90s Fahrenheit (32–34 °C). Conversely, mean low temperatures in early to mid-January range from the low 40s Fahrenheit (4–7 °C) in north Florida to above 60 °F (16 °C) from Miami southward, with South Florida rarely experiencing freezing temperatures. The state’s record high temperature of 109 °F (43 °C) was set in Monticello in 1931, while the record low of −2 °F (−19 °C) occurred in Tallahassee in 1899, highlighting the broader temperature variability in the northern regions.

Due to its subtropical and tropical nature, measurable snowfall is exceptionally rare in Florida, typically occurring only on isolated occasions in the farthest northern regions like Jacksonville, Gainesville, or Pensacola. Frost, however, is more common, particularly in the panhandle. The state’s plant hardiness zones range widely from zone 8a in the inland western panhandle to zone 11b in the lower Florida Keys, reflecting its diverse microclimates. Fog is also a common atmospheric phenomenon across the state. In terms of sunshine, a narrow eastern part of the state, including Orlando and Jacksonville, receives between 2,400 and 2,800 hours annually, while the remainder, encompassing Miami, enjoys an even greater abundance, with 2,800 to 3,200 hours annually.

13. **Natural Phenomena and the Threat of Hurricanes**

Despite its popular moniker, the “Sunshine State,” Florida is no stranger to severe weather events. Central Florida, in particular, holds the distinction of being the lightning capital of the United States, experiencing more lightning strikes than anywhere else in the country. The state also receives one of the highest average precipitation levels nationwide, largely attributed to the frequent afternoon thunderstorms that sweep across much of the state from late spring through early autumn, contributing to its lush landscapes and extensive wetlands.

Florida also leads the United States in tornadoes per area, a statistic that includes waterspouts, which are common over its coastal waters. While tornadoes are a regular occurrence, they do not typically attain the intensity seen in the Midwest and Great Plains regions, though hail frequently accompanies the most severe thunderstorms. These weather phenomena underscore the dynamic atmospheric conditions characteristic of Florida’s climate.

The most significant and persistent natural threat to Florida each year is hurricanes, with the official season running from June 1 to November 30, and peak activity typically occurring from August to October. Given its lengthy coastline bordered by subtropical or tropical waters, Florida is the most hurricane-prone state in the U.S. Historically, a staggering 83% of all Category 4 or higher storms that have struck the United States have made landfall in either Florida or Texas. Between 1851 and 2006, Florida was impacted by 114 hurricanes, with 37 of these being major storms (Category 3 and above), making it rare for a hurricane season to pass without at least a tropical storm making an impact on the state. A notable example is Hurricane Andrew in 1992, which caused over $25 billion in damages, holding the distinction as the costliest weather disaster in U.S. history until 2005, and remaining the second-costliest hurricane in Florida’s history.

14. **Florida’s Remarkable Biodiversity and Unique Wildlife**

Florida is a vibrant ecological tapestry, home to an astonishing array of wildlife and unique ecosystems that contribute significantly to its natural heritage. Among its most iconic natural treasures is Everglades National Park, recognized as the largest tropical wilderness in the U.S. and one of the largest in the Americas, a vast wetland teeming with life. Complementing this, the Florida Reef stands as the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States, and impressively, it is the third-largest coral barrier reef system in the world, surpassed only by the Great Barrier Reef and the Belize Barrier Reef, highlighting the state’s exceptional marine biodiversity.

The state’s marine mammals are particularly captivating, including the graceful bottlenose dolphin, the social short-finned pilot whale, the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, and the gentle West Indian manatee. These species thrive in Florida’s warm coastal and estuarine waters, serving as critical indicators of the health of its aquatic environments. Their presence underscores the importance of ongoing conservation efforts to protect these vulnerable populations and their habitats.

On land, Florida hosts a diverse range of mammals that navigate its varied landscapes, from dense forests to marshy wetlands. This impressive list includes the elusive Florida panther, the industrious northern river otter, mink, eastern cottontail rabbit, marsh rabbit, raccoon, striped skunk, various squirrel species, white-tailed deer, the diminutive Key deer, bobcats, red fox, gray fox, coyote, wild boar, the Florida black bear, nine-banded armadillos, and the Virginia opossum. The state’s reptilian inhabitants are equally fascinating, featuring the formidable American alligator, American crocodile, along with venomous snakes like the eastern diamondback and pygmy rattlesnakes, and endangered species such as the gopher tortoise, green, and leatherback sea turtles. This rich tapestry of fauna makes Florida a truly extraordinary place for wildlife enthusiasts.

From its pivotal role in the nation’s expansion and its resilience through periods of conflict and change, to its unique climatic zones and unparalleled biodiversity, Florida continues to be a state of remarkable complexity and enduring allure. Its journey from a contested colonial outpost to a modern demographic and economic powerhouse, all while preserving its distinct natural wonders, paints a portrait of a state constantly evolving, yet deeply rooted in its vibrant history and environment.