In the grand tapestry of human history, few narratives are as compelling as the dramatic global doubling of our life expectancy. This monumental achievement, arguably the most significant thing that has ever happened to humanity, stands as a testament to relentless scientific inquiry and the profound evolution of medical understanding. Yet, it’s easy to forget the not-so-distant past when life was a far more precarious affair, a constant negotiation with unseen threats and inexplicable maladies. The mid-19th century, in particular, offers a stark and often unsettling glimpse into this reality, a time when the very act of living was fraught with dangers that today seem almost unfathomable.

The year 1850 provides a poignant benchmark. Medical diagnostics were rudimentary at best, autopsies were rare, and reliable data scarce. The nosology, or classification of human diseases, developed for the 1850 Mortality Census, was, by necessity, crude. It cataloged 300,000 American deaths across 170 categories, many of which would be unrecognizable to a modern physician. Some listed conditions, such as abscess, canker, carbuncle, cramp, eruption, hemorrhoids, spasms, teething, tetter, and thrush, do not normally kill in themselves, suggesting that people more often died *with* these ailments rather than *of* them. This rudimentary classification system, while medically inaccurate by today’s standards, nonetheless offers a profound window into how an earlier society grappled with the discipline of death, attempting to constrain its terrifying unpredictability into careful, albeit imperfect, categories.

What emerges from this historical record is a powerful revelation: a significant portion of the suffering and death in the 19th century stemmed from conditions that are now not just treatable, but often easily preventable or curable. Many lives were cut short by simple vitamin deficiencies or bacterial infections that modern medicine can swiftly address with a multivitamin, a sensible diet, or a course of antibiotics. Embark on a journey with us as we uncover seven of these once-deadly adversaries, exploring their devastating impact on past populations and celebrating the triumphs of modern science that have transformed them into mere footnotes in the medical textbooks of today.

1. **Black Tongue: The Silent Ravager of Nutrition**Imagine a world where the very tongue could turn dark, a harbinger of a swift and agonizing end. This was the terrifying reality of ‘Black Tongue’ in the 19th century, a condition that, as its name vividly implies, manifested as a dark discoloration of the tongue. This alarming symptom was often indicative of severe underlying conditions such as typhoid or diphtheria, highly contagious infections that spread rapidly through communities. The conventional wisdom of the era dictated strict quarantine for affected individuals, a desperate measure to stem the tide of its relentless progression.

Nineteenth-century treatments, as recorded in sources like The American Journal Medical Sciences, reflect the era’s limited understanding and often drastic approaches. Patients might be administered nitrate silver, a potent chemical, or, remarkably, “as much brandy as the patient can digest.” These interventions, while perhaps offering some symptomatic relief or perceived comfort, did little to address the root cause, particularly in later decades. The tragedy deepened when it was recognized that Black Tongue could also signal a fatal vitamin deficiency, particularly among the most vulnerable: impoverished infants and children.

The modern understanding of ‘Black Tongue’ reveals a complex history. While the term could refer to specific infections, its connection to fatal vitamin deficiencies points strongly towards conditions like pellagra, a severe niacin (Vitamin B3) deficiency. In the 21st century, pellagra is exceedingly rare in developed nations, thanks to fortified foods and accessible nutrition. Its treatment is remarkably simple: dietary improvements, often coupled with niacin supplementation, can reverse the devastating effects and prevent the agonizing progression that once led to death, a stark contrast to the despair of the 1800s.

2. **Chlorosis: The Green-Sickness and Its Irony**Chlorosis, romantically but tragically known as the “green-sickness” in the 19th century, paints a vivid picture of a widespread ailment that disproportionately affected young women. This condition, characterized by a distinct pale or greenish tinge to the skin, was in fact anemia caused by an iron deficiency. It was a disease that transcended social strata, afflicting both the opulent and the impoverished. As Egbert Guernsey observed, “servants, and especially cooks, are particularly liable to this disease, but the delicate and inert habits of the rich not less frequently lead to this affliction.” This societal reach underscores the pervasive nutritional challenges of the time, regardless of economic standing.

The symptoms of chlorosis extended beyond mere pallor. Sufferers experienced brittle fingernails, swollen ankles, and irregular menstruation, all clear indicators of a body struggling with insufficient iron. The 19th-century medical advice, while lacking a precise understanding of iron’s role, intuitively grasped parts of the solution. Recommendations included a wholesome diet, plenty of exercise, and even the therapeutic benefits of fresh sea air – early forms of lifestyle interventions that contained elements of truth.

Today, chlorosis is a condition we recognize as iron-deficiency anemia, a highly treatable and preventable ailment. A simple blood test can diagnose it, and the cure is straightforward: dietary adjustments to include iron-rich foods, often supplemented with oral iron tablets. What was once a debilitating and often fatal “green-sickness” that drained the vitality from countless young lives is now managed with relative ease, a testament to our profound understanding of human nutritional needs.

3. **Dirt Eating: A Crying Need for Sustenance**The practice of ‘dirt eating,’ or geophagia as it is scientifically known today, might seem bizarre and primitive, but in the 19th century, it was a grim symptom of deep-seated medical distress. Far from a mere peculiar habit, it was an alarming manifestation of anemia, internal parasites, or severe vitamin and mineral deficiencies. The context reveals a particularly disturbing aspect of this phenomenon, especially in the American South, where enslaved people were often forced to consume a specific chalky clay known as kaolin, referred to as “white dirt.” Austin Flint, in the 1860s, documented this “morbid habit” among plantation negroes, and his proposed “treatments” — chaining slaves to plank floors or gagging them with iron or tin face masks — reflect an era of brutal dehumanization and a profound misunderstanding of the underlying biological drivers.

However, dirt eating was not confined to enslaved populations. Poor white Southerners also engaged in the practice, highlighting that it was a symptom of systemic poverty and malnutrition across the region. An 1894 study noted that twenty-six percent of Dr. Sandwith’s patients confessed to “earth hunger,” revealing the widespread nature of this desperate coping mechanism. For these individuals, the consumption of kaolin was likely an attempt by a body starved of essential nutrients to find relief, even if it exacerbated their health problems.

In the modern era, geophagia is understood as pica, a disorder characterized by cravings for non-nutritive substances. It is almost invariably linked to nutrient deficiencies, particularly iron or zinc, or to internal parasitic infections. The solutions are mercifully simple and humane: comprehensive nutritional assessment, supplementation with the missing vitamins or minerals, and antiparasitic medication where indicated. This tragic chapter of history, marked by suffering and ignorance, now serves as a powerful reminder of the fundamental human need for adequate nutrition and compassionate care.

4. **Rickets: The Silent War Against Bone Development**Among the many scourges that afflicted children in the 19th century, rickets stood out as a particularly debilitating and, in some cases, fatal condition. Described by Dr. Eustace Smith as “one of the most preventable” but distressingly common children’s illnesses, rickets was primarily caused by a severe deficiency of Vitamin D. This crucial vitamin, essential for calcium absorption and bone mineralization, was often lacking in the diets and lifestyles of children, particularly those living in urban, industrialized environments with limited sun exposure.

The physical manifestations of rickets were heart-wrenching. Affected children suffered from deformities of the skull, leading to abnormally shaped heads. Their legs often became bowed, and the spine could curve, leading to permanent bodily malformations. Developmental delays were common, and in severe instances, the disease could culminate in death. Dr. Smith’s evocative description of a “rickety child” — only happy at rest, anticipating “the weight of years” with the “face and figure of a child” — underscores the profound impact on both physical and mental well-being.

Fortunately, rickets is a condition that modern medicine has largely conquered. The understanding of Vitamin D’s role has led to simple and highly effective preventative measures, including dietary fortification (milk, cereals), Vitamin D supplementation, and adequate, safe sun exposure. Treatment for existing cases involves high-dose Vitamin D, which can reverse many of the bone deformities if caught early. The stark contrast between the widespread suffering of rickety children in the 1800s and the rarity of the disease today exemplifies a triumphant public health victory, a clear marker of progress in safeguarding childhood.

Read more about: Unmasking the Silent Threat: 11 Critical Insights into Vitamin D Deficiency and Its Impact on Your Health

5. **Scurvy: The Mariner’s Curse Unveiled**For centuries, scurvy stalked humanity, particularly those on long voyages or confined to circumstances that restricted access to fresh produce. In the 19th century, it remained a formidable foe, associated with sailors, soldiers, paupers, prisoners, and residents of lunatic asylums – anyone whose diet lacked crucial fresh foods. This insidious disease, born from a profound Vitamin C deficiency, slowly but surely eroded the body’s defenses, leading to a host of agonizing symptoms that often proved fatal.

Victims of scurvy experienced profound anemia, leaving them exhausted and weak. Bleeding became a common and distressing symptom, manifesting as widespread bruising, gum hemorrhages, and ultimately, the painful loosening and loss of teeth. Their bodies ached, and extremities would swell, a testament to the systemic breakdown caused by the missing nutrient. Despite James Lind, a British naval surgeon, having discovered the link to diet as early as 1753, widespread implementation of preventative measures was slow, and countless lives continued to be lost throughout the 1800s.

The modern solution to scurvy is almost deceptively simple: the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and especially citrus and potatoes. Vitamin C supplements are readily available and highly effective. This once-terrifying affliction, capable of decimating crews and communities, is now easily preventable and treatable, standing as a powerful symbol of nutritional science’s ability to transform human health. The historical accounts of scurvy serve as a vivid reminder of the critical importance of a balanced diet and the incredible power of a single vitamin.

6. **Canker Rash: Scarlet Fever’s Deceptive Guise**In the bustling, often unsanitary environments of the 19th century, ‘Canker Rash’ struck fear into the hearts of parents and physicians alike. This wasn’t merely a minor irritation; it was a particularly virulent form of scarlet fever, accompanied by ulcerations or a “putrid sore throat.” William Andrus Alcott starkly described it as “a very troublesome disease,” not infrequently fatal, declaring that “Physicians dread it almost as much as they do the small-pox.” Its prevalence was higher among children, making it a constant threat to the youngest and most vulnerable members of society.

The symptoms were alarming and swift: chills, a high fever, a painfully sore throat, and a characteristic skin rash. These signs indicated a severe systemic infection that, without effective treatment, could rapidly overwhelm the body. Nineteenth-century treatments were largely palliative – bed rest, “cooling drinks given freely,” “abstinence from animal food,” and cold compresses. While these might offer some comfort, they did nothing to combat the bacterial pathogen at its core, leaving recovery to chance and the patient’s own resilience.

Today, the fear associated with scarlet fever has dramatically receded. We now understand it to be a bacterial infection, typically caused by *Streptococcus pyogenes*. The advent of antibiotics in the 20th century revolutionized its treatment. A simple course of penicillin or other appropriate antibiotics can quickly and effectively cure the infection, preventing the serious complications and fatalities that were once so common. The dramatic shift from a dreaded, often fatal childhood illness to a readily treatable condition underscores the transformative impact of modern antimicrobial therapies.

7. **Carbuncle: From Fatal Infection to Manageable Ailment**The presence of a carbuncle in the 19th century was far more ominous than a mere skin irritation; it represented a grave threat that often led to agonizing death. These were not small boils but formidable groupings of inflamed, pus-filled bumps, significantly larger than typical abscesses. Described in A System of Surgery, a carbuncle could grow to the size of a human hand, commonly forming on the neck, shoulders, back, or buttocks, areas vulnerable to friction and contamination. Its appearance signaled a severe bacterial infection, deep within the tissue, that could rapidly spiral out of control.

Early 19th-century interventions were rudimentary, typically involving lancing the carbuncle with a “tenotomy knife” to drain the pus. However, if the infection was not caught in its nascent stages, or if it proved particularly aggressive, the consequences were dire. Infected carbuncles frequently progressed to gangrene, a terrifying condition where tissue death occurred due to a lack of blood supply, often exacerbated by rampant bacterial proliferation. In such cases, the only desperate measure to save the patient’s life was amputation of the affected limb, an agonizing procedure with high rates of shock and death, or, tragically, the infection would simply prove fatal.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the threat of carbuncles has been dramatically diminished. While still a serious infection, modern medicine has an array of powerful tools. Antibiotics, both oral and intravenous, can swiftly target and eliminate the bacterial culprits, preventing the spread of infection and the onset of gangrene. Surgical drainage remains important, but it is now complemented by sophisticated wound care and pain management. What was once a life-threatening, disfiguring ordeal in the 1800s is now a manageable ailment, typically resolved with a combination of medication and minor procedures, a testament to the profound advancements in infectious disease management.” , “_words_section1”: “1945

8. **Croup: The Barking Malady That Silenced Childhood**The tender years of infancy and early childhood in the 19th century were a treacherous journey, fraught with illnesses that could snatch lives away with terrifying swiftness. Among these, croup, also known as cynanche trachealis, was a particularly feared adversary for parents. This infection caused a severe swelling of the larynx and an obstruction of the upper airways, leading to heartbreaking struggles for breath. The tell-tale signs were unmistakable: raspy breathing and a distinctive cough, often described as sounding eerily similar to the barking of a dog or seal, shattering the quiet of the night.

Children afflicted with croup would experience violent, sporadic attacks of coughing and acute shortness of breath, leaving families in agonizing helplessness. The medical literature of the era paints a grim picture of the desperation and despair. Homoeopathic Domestic Practice, a guide for families, starkly noted that in severe cases, croup often culminated in death. So profound was the suffering that it described a mother watching “with bitter agony the fearful struggles of her child,” breathing “a sigh of relief as the last breath is drawn, and as the look of anguish changes to the sweet calm of death, she knows that suffering is over, and her little one is at rest.” This poignant passage underscores the tragic reality of how common and fatal this condition was.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the terrifying grip of croup has largely been loosened. Modern medicine has a much clearer understanding of the viral pathogens, typically parainfluenza or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), that cause most cases of croup. While still a distressing experience for children and their parents, current treatments focus on reducing inflammation and easing breathing. Steroids, humidified air, and in more severe instances, nebulized epinephrine are highly effective interventions that have transformed croup from a potential death sentence into a condition that, while requiring medical attention, is almost always treatable, preventing the agonizing suffocations of the past.

The advancements in medical care, from improved hygiene to a deeper understanding of respiratory physiology and pharmacology, mean that the vast majority of children who contract croup today make a full recovery. The image of a child gasping for air, a common and fatal sight in the 1800s, has been relegated to the annals of history, a powerful testament to the relentless march of medical progress and public health initiatives that protect our most vulnerable. What was once a source of bitter agony for families is now a manageable illness, ensuring that the “sweet calm of death” is not the expected outcome for a child struggling to breathe.

9. **Puerperal Fever: The Silent Scourge of Childbirth**For women in the 19th century, the act of childbirth, a moment of profound joy and hope, was often shadowed by the terrifying specter of puerperal fever, ominously known as “Child-Bed Fever.” This wasn’t merely a complication; it was a deadly infection of the uterus, a brutal reality that made lying-in hospitals of the era perilous places. The experience of this fever was agonizing, characterized by a rapid onset of high fever, a racing pulse, intense thirst, and excruciating, radiating pain throughout the abdomen, turning the post-delivery period into a desperate struggle for survival.

The profound fear associated with puerperal fever is vividly captured in historical texts. Egbert Guernsey’s Homoeopathic Domestic Practice, published in 1856, described it chillingly as “the dread of mothers.” This condition was recognized as exceptionally serious and, all too frequently, fatal. Medical advice of the time emphasized the urgency of seeking a physician “be consulted without delay, for if allowed to go on, it may gain a fearful ascendency.” Yet, even with medical consultation, treatments were rudimentary, typically involving doses of aconite alternated with bryonia or belladonna, which offered little defense against the rampant bacterial infection.

Nineteenth-century physicians noted that puerperal fever was particularly lethal in births occurring between January and March, suggesting seasonal or environmental factors, though the true cause remained elusive. The tragic irony was that the very hands of the healers, unknowingly, often spread the infection. Without an understanding of germ theory, doctors and midwives could carry bacteria from one patient to another, inadvertently contributing to the devastating mortality rates in maternity wards, transforming what should have been a sacred passage into a gateway to despair.

Today, puerperal fever is understood as maternal sepsis, a condition that, while still serious, is largely preventable and highly treatable. The revolutionary discovery of germ theory by Ignaz Semmelweis and Louis Pasteur, followed by the development of antibiotics in the 20th century, transformed maternal healthcare. Strict hygiene protocols, antiseptic techniques during delivery, and the swift administration of antibiotics have dramatically reduced its incidence and fatality. The “dread of mothers” that once haunted every childbirth is now a rare occurrence, a monumental triumph of modern obstetrics and public health, ensuring that childbirth is, overwhelmingly, a safe and joyous event.

10. **Ship Fever: The Tyranny of Typhus on the High Seas**In the crowded, often inhumane conditions of 19th-century transit, particularly aboard the vast emigrant ships crossing oceans, a relentless adversary known as ‘Ship Fever’ wreaked havoc. This wasn’t a romantic affliction but a brutal bacterial infection, epidemic typhus, spread by the unseen menace of lice and fleas. The unsanitary environments of these vessels, teeming with desperate passengers seeking new lives, provided the perfect breeding ground for the disease, turning voyages into nightmarish journeys of sickness and death.

Henry Grafton Clark, in 1850, painted a harrowing picture of the plight of the immigrant victim. He observed that ship fever “has been seen on board emigrant ships, in the quarantine hospitals, and among emigrants newly arrived from Europe.” His words convey the deep despair, describing how the fever “wastes his strength on the long passage, and at last, with its fiend-like gripe, thrusts him down into the deep and sorrowful ocean, or only spares him from this, that he may find but a ‘hospitable grave’ upon the shores of the country of his most ardent hopes and expectations.” The disease not only claimed lives but also inflicted delirious episodes upon those who, against all odds, managed to recover, leaving a lasting mark on their minds and bodies.

The treatments available in the 19th century were a testament to the limited understanding of infectious diseases. Recommendations included cleanliness and ventilation, which, while beneficial, were often impossible to achieve in the cramped quarters of a ship. Other interventions, such as “Dover’s Powder,” camphor, spirit of nitrate, or “liquor ammoniae acetatis,” were largely symptomatic and failed to address the underlying bacterial cause. Ship Fever thus continued its devastating sweep, decimating populations in transit and leaving behind a trail of sorrow and mass graves, a stark reminder of the fragile balance between human aspiration and biological threat.

The 21st century has seen the near eradication of epidemic typhus in most parts of the world, a testament to monumental public health achievements. Improved sanitation, vector control (the elimination of lice and fleas), and the development of effective antibiotics have transformed this once-terrifying killer into a rare and treatable condition. Today, a simple course of antibiotics can swiftly cure typhus, preventing the widespread fatalities and the agonizing delirium that once defined the fate of countless immigrants. The ghost of Ship Fever, though a potent historical reminder, no longer holds dominion over those seeking new horizons.

11. **Tetanus: The Grip of Lockjaw, Once Unyielding**Few diseases in the 19th century struck with such chilling finality and agony as tetanus, universally known as lockjaw. This bacterial infection, caused by *Clostridium tetani*, typically entered the body through an open wound, transforming a seemingly minor injury into a death sentence. The initial symptoms were insidious, often starting with a tightening in the head and neck, a prelude to the agonizing difficulty in opening the mouth. This characteristic “lockjaw” was just the beginning of a terrifying progression that would paralyze the entire body.

As the infection advanced, all voluntary muscles in the body would gradually tighten and become demobilized, leading to severe, painful spasms. The patient’s body might arch into an unnatural bow, a condition known as opisthotonos, while consciousness remained intact, forcing them to endure every moment of their torment. Homoeopathic Domestic Practice noted that the illness could be triggered by various factors, from a splinter or a blow on the back to fever or “violent exertion of the mind and body.” The grim prognosis was clear: “Regardless of the treatment, the disease was most often fatal.”

The medical community of the 1800s was largely helpless against the relentless progression of tetanus. Without antibiotics to combat the bacteria or antitoxins to neutralize its potent neurotoxins, physicians could only offer palliative care, which provided little relief. The disease’s profound lethality meant that once the characteristic symptoms of lockjaw set in, death was almost an inevitable outcome, a horrifying end marked by prolonged suffering and the complete loss of bodily control. It was a condition that underscored the vulnerability of human life to microscopic threats.

Today, tetanus is a largely preventable disease, thanks to the widespread availability and efficacy of the tetanus vaccine. Routine childhood immunization, booster shots throughout adulthood, and immediate wound care for potentially contaminated injuries have dramatically reduced its incidence. For those who do contract it, modern intensive care, including muscle relaxants, ventilators, and tetanus antitoxin, offers a fighting chance. What was once a universally fatal and agonizing affliction is now a preventable tragedy, a triumph of vaccination and advanced medical support.

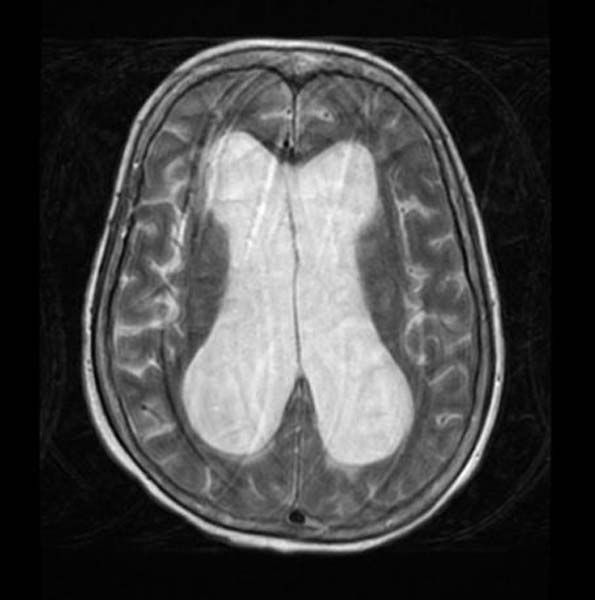

12. **Hydrocephalus: The Shadow of “Water-Stroke” over Childhood**The delicate brains of infants and young children in the 19th century were tragically susceptible to hydrocephalus, a condition ominously termed “water-stroke.” This devastating ailment involved the accumulation of fluid deep within the brain, leading to severe pressure and irreversible damage. The symptoms were heartbreakingly clear: persistent headaches, recurrent vomiting, profound fatigue, and often, a fever. As the disease progressed, the final stages brought convulsions, deep unconsciousness, and ultimately, death, leaving families shattered by the swift decline of their little ones.

The severity of hydrocephalus in the 1800s cannot be overstated. Historical accounts reveal a desperate struggle against a largely untreatable condition. Treatments were limited to basic interventions such as cold compresses to the head and administering doses of aconite or belladonna, which did little to address the underlying accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid. The prognosis was dire; hydrocephalus “kills more than recovers,” a chilling statistic that highlights its extreme lethality and the profound helplessness faced by parents and physicians alike when confronted with this cruel affliction.

The anatomical and physiological understanding of the brain and its fluid systems was rudimentary, meaning there was no effective way to drain the excess fluid or understand the various causes. Whether it was congenital, caused by infection, or a complication of birth, the outcome was almost universally grim. The “water-stroke” robbed children of their potential, often leaving them with profound neurological impairment before finally succumbing, a stark reminder of the limits of medical science in an era before neurosurgery and advanced imaging.

In the 21st century, the outlook for children diagnosed with hydrocephalus has been profoundly transformed. Thanks to advancements in neurosurgery, the condition is now manageable through the surgical implantation of shunts. These tiny tubes divert excess cerebrospinal fluid from the brain to another part of the body, such as the abdomen, where it can be absorbed. This procedure, coupled with improved diagnostics like MRI and CT scans, allows for early detection and intervention, saving countless lives and enabling many children to live full, healthy lives. The once “extremely deadly” hydrocephalus is now a treatable condition, marking an incredible leap in pediatric neurology and surgical capabilities.

13. **Milk Sickness: The Mysterious Killer from the Land**In the early 1800s, particularly in the nascent communities of the American South and West, a mysterious and terrifying malady known as ‘milk sickness’ swept through rural families. It was referred to as a “mysterious disease” or “Sick-stomach,” and its impact was devastating, often manifesting as an epidemic where numerous individuals in a community would fall ill simultaneously. This wasn’t a contagious infection passed from person to person, but an insidious form of food poisoning with an unknown origin, which made it all the more frightening and difficult to combat.

The symptoms of milk sickness were agonizing: relentless nausea, debilitating dizziness, severe vomiting, and a noticeably swollen tongue. As death approached, patients developed “a pronounced odor on the breath and in the urine,” a grim signature of the body’s systemic collapse. Pioneer communities, moving into new territories, encountered this illness with tragic frequency, often losing entire families, including prominent figures like Abraham Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, to its fatal embrace. The inability to identify its cause fueled superstitions and fear, leading to desperate and ineffective treatments such as opium, brandy, charcoal, strychnine, or even blood-letting.

For decades, the source of this deadly sickness remained an enigma, leading to widespread panic and the abandonment of newly settled lands. It wasn’t until the late 1910s and early 1920s that physicians finally unraveled the mystery: milk sickness was caused by drinking the milk of a cow that had ingested white snakeroot (*Ageratina altissima*), a poisonous plant. The toxin, tremetol, accumulated in the milk, silently turning a staple food into a deadly poison. This breakthrough was a monumental step, turning a “mysterious disease” into a diagnosable condition with a clear cause.

Today, milk sickness is an extremely rare form of food poisoning, almost entirely eradicated thanks to agricultural advancements and public health education. Farmers are aware of the dangers of white snakeroot and actively manage pastures to remove it, while modern food safety regulations ensure the milk supply is safe. What was once a widespread, inexplicable, and extremely fatal epidemic that haunted pioneer settlements is now a historical curiosity, a powerful illustration of how scientific understanding and preventative measures can conquer even the most enigmatic of adversaries, transforming a deadly environmental threat into a footnote in medical history.

Our journey through the grim medical landscape of the 19th century, confronting the phantom of croup, the dread of puerperal fever, the tyranny of ship fever, the unyielding grip of tetanus, the shadow of hydrocephalus, and the mystery of milk sickness, serves as a profound reminder. It is a testament to the sheer ingenuity and unwavering dedication of countless scientists, doctors, and public health advocates who, step by painstaking step, have peeled back the layers of ignorance and disease. From the simplest vitamin supplement to the most complex surgical intervention, from public sanitation to life-saving vaccines, humanity has systematically dismantled the dominion of these once-unstoppable killers. The stark contrast between the pervasive suffering of the past and the vastly improved health outcomes of today is not just a triumph of science, but a beacon of hope, illuminating the boundless potential for future advancements in our unending quest for longer, healthier, and more dignified lives.