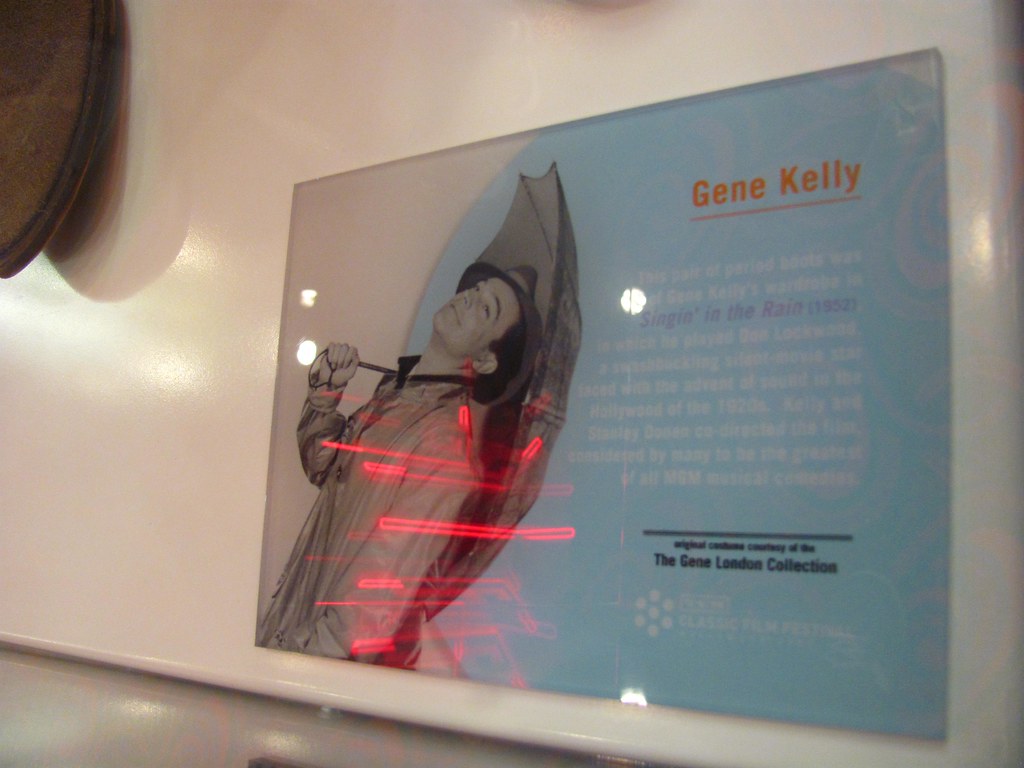

Eugene Curran Kelly, the American dancer, actor, singer, director, and choreographer, remains an indelible figure in the annals of Hollywood’s golden age. Known for his athletic and energetic dancing style, Kelly revolutionized the film musical, shaping it into an art form accessible to the general public, a concept he famously termed “dance for the common man.” His iconic performances in films like “Singin’ in the Rain” and “An American in Paris” cemented his status as a legendary entertainer whose influence continues to resonate decades after his passing.

Yet, beyond the dazzling spotlight of his cinematic achievements, Kelly’s personal life, particularly his final years, unfolded with a quiet dignity often shielded from public scrutiny. His death in 1996, at the age of 83, followed a prolonged battle with illness and a series of strokes. It was a period during which he faced the end of his life with a grace and profound thoughtfulness that, until recently, remained largely a private testament shared primarily with his third wife, Patricia Ward Kelly.

Patricia Ward Kelly, who married the star shortly before his death, has since offered an intimate glimpse into those final days, revealing deeply personal decisions made by the legendary actor. Her forthcoming show, “Gene Kelly The Legacy,” promises to illuminate a side of the artist rarely seen, including his explicit wishes regarding his own passing and the unconventional decision to forgo a traditional funeral, a choice that undoubtedly surprised many at the time but stemmed from a life lived under an unyielding public gaze. This article delves into these revelations, exploring the personal journey of an icon navigating his final curtain call.

1. **The Unconventional Farewell: Gene Kelly’s Choice to Forgo a Public Funeral**

In 1996, the world mourned the loss of Gene Kelly, but many were left to wonder why no public funeral or memorial service was held for the beloved “Singin’ in the Rain” star. This deviation from tradition was not an oversight, but a deliberate choice, as revealed by his widow, Patricia Ward Kelly. She disclosed that the wish to shun a formal funeral came directly from Kelly himself before he passed away, a testament to his desire for privacy even in death.

Patricia explained that her late husband was “very specific” about his final arrangements. He had taken the time to write out his wishes, even having them notarized, to ensure they would be honored. This level of foresight and planning underscores a profound intention behind his decision, reflecting a man who had considered the final act of his life with the same meticulousness he applied to his iconic dance routines.

The reasoning behind this seemingly surprising choice was deeply personal and rooted in his experiences with a life lived in the public eye. “He didn’t want to be buried anywhere,” Patricia recounted, recalling his sentiment: “I’m tired of being on a tour bus route. Every time we would leave our house the tour bus would be going by and would follow us.” This candid statement illuminates the burden of relentless celebrity and his yearning for a final, undisturbed peace.

For Kelly, the concept was simpler, more elemental: “‘For me it’s dust to dust’,” he stated, indicating that he “didn’t need to have a big memorial some place.” This perspective suggests a desire to transcend the physical trappings of mourning and the need for a specific pilgrimage site, choosing instead a more spiritual or internal remembrance for those who loved him. His widow echoed this sentiment, stating, “For me, he’s just always here, so I don’t need to go to a particular spot to mourn him.”

This thoughtful approach to his own mortality was also informed by observing the passing of his peers. Kelly “saw what happened to them,” having “sat through a lot of memorial services and visited a lot of gravesites.” These experiences, Patricia noted, helped to guide his choices, allowing him to define an end that truly resonated with his personal philosophy and a lifetime spent under the unblinking gaze of the world.

2. **A Quiet Battle: Confronting Illness and Strokes in His Final Chapter**

Gene Kelly’s final years were marked by a period of declining health, a struggle with illness that included a series of strokes leading up to his death in February 1996. Patricia Ward Kelly, his devoted wife, shared an intimate account of these challenging times, revealing that much of his suffering was deliberately kept out of the press, a concerted effort to maintain his dignity and privacy.

She described a life of careful navigation, where they would “sneak into hospitals as best we could” to avoid the relentless glare of media attention. This dedication to shielding him from public intrusion highlights the immense pressure and lack of personal space that often accompany immense fame, even during moments of profound vulnerability and ill health.

Despite the physical toll and the constant battle for privacy, Kelly faced “the end of his life with such grace and such dignity.” His widow recalled this period as “really a lesson in how to deal with difficulty,” underscoring his resilience and composure. It was not just a time of challenge, but also one of deep connection for the couple, described by Patricia as “really a bonding time for the two of us.”

This phase of his life, though arduous, forged an even stronger bond between Gene and Patricia. As she prepared to embark on her “Gene Kelly The Legacy” tour, she emphasized the importance of discussing these aspects, stating, “I talk about this in the show because a lot of people don’t talk about the end of life, and I think it’s really integral. It’s part of it, talking about grief and loss.” Her willingness to share these experiences now serves to honor his grace and to offer a rare, humanizing perspective on a celebrated figure.

3. **Patricia Ward Kelly: A Decade of Devotion and Unwavering Support**

The relationship between Gene Kelly and Patricia Ward Kelly blossomed after an initial professional encounter in 1985. They first met at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., where Kelly was hosting a television special about the museum and Patricia was working as a writer on the project. This collaborative beginning laid the groundwork for a personal connection that would transcend professional boundaries.

Despite a significant 47-year age gap, their bond deepened, leading to more than a decade of what Patricia described as “blissful happiness together.” Their partnership evolved beyond companionship, with Patricia taking on the crucial role of caregiver as Kelly’s health declined. She remained a steadfast presence by his side, providing comfort and support through his illness.

During their time together, Patricia was also helping Kelly document his memories for a book about his life. This endeavor proved invaluable, as she consequently “has records of almost all of their conversations and movements.” This meticulous documentation not only served a literary purpose but also provided a personal coping mechanism for Patricia during his difficult final years, allowing her to process and preserve their shared experiences.

Her commitment extended to navigating the complexities of his health and fame. Patricia’s quiet strength and unwavering dedication during a period of intense personal and public pressure speak volumes about the depth of their relationship. Her narrative offers a poignant insight into the private world of a star, cared for by someone who understood the true essence of his being beyond the public persona.

4. **The Price of Stardom: Battling Media Intrusion During Private Suffering**

The celebrity status that Gene Kelly had cultivated over decades, while bringing him immense adulation, also subjected him to intense and often intrusive media scrutiny, particularly during his final illness. Patricia Ward Kelly candidly recounted the invasive nature of the press in the 1990s, stating, “patient confidentiality wasn’t so much of a thing in the ’90s.” This lack of ethical boundaries meant that their private struggles became fodder for public consumption.

The couple faced egregious breaches of privacy, with nurses allegedly “selling stories to the press about Gene as he battled illness in his final years.” This betrayal of trust within the healthcare system highlights the severe ethical challenges faced by celebrities seeking medical care. The relentless pursuit of a story extended to absurd lengths, with Patricia claiming that “some journalists even dressed up as priests to sneak in themselves.”

Patricia described the situation as “awful,” challenging the common assumption that “a celebrity will have the best care and privacy. Instead, she asserted, “In fact, I think it’s very, very hard for a celebrity, very difficult.” This stark reality underscores the unique vulnerabilities faced by public figures, even in their most personal and vulnerable moments, as they contend with a pervasive culture of sensationalism.

Paradoxically, this shared ordeal strengthened the couple’s bond. “But in a way it brought us closer,” Patricia explained, “we were fighting the same fight.” The external pressure created an internal solidarity, transforming their battle against illness and intrusion into a collective effort. For Patricia, chronicling their experiences served as a coping mechanism: “Of course, I was writing down everything, which was a way for me to cope. As long as I was writing, he was still alive.” The act of writing became a lifeline, delaying the inevitable and preserving his presence.

5. **Openness in the Face of Mortality: Kelly’s Candid Discussions on End of Life**

While death was a topic Patricia Ward Kelly had grown up discussing openly within her family, it was not initially a subject she broached with Gene Kelly. However, as he aged and his health declined, their conversations evolved, leading to a remarkable openness on his part about his final wishes. This transition from a previously unspoken subject to frank discussion showcased Kelly’s profound capacity for introspection and honesty.

Patricia expressed immense pride in how open he became, emphasizing her desire to understand his exact preferences: “I just felt that I wanted to know exactly what he wanted.” She made a solemn promise to him, assuring him, “I would do exactly what he wanted me to do,” thereby establishing a foundation of trust that allowed for such sensitive discussions. This commitment provided Kelly with the comfort of knowing his desires would be respected.

His willingness to engage in these discussions was particularly notable for a man of his generation and stature. Patricia reflected, “I think it was really good for him because here was a guy from a different generation talking about things that you just generally didn’t talk about.” She credited him with considerable courage “for a man of that age and that stature to really assess and reassess his life and also to consider the end of life as frankly as he did, and lay it out.”

This frankness was a source of great admiration for Patricia, who stated, “I was very proud of him.” Beyond personal pride, this clarity also served as a profound guide for her. “And it helped me a lot because I knew, people have such interesting feelings and thoughts about death and the final days, so I just needed to know what he wanted.” Her adherence to his wishes provided her with an unshakeable conviction, ensuring that she could face any public scrutiny with the knowledge that she had honored her promise.

6. **”Dust to Dust”: Gene Kelly’s Specific Instructions for His Final Disposition**

Gene Kelly’s wishes for his final disposition were remarkably clear and detailed, emphasizing a desire for absolute privacy and a departure from conventional practices. He explicitly did not want to be buried in any specific location, articulating his reasons with a blend of weariness and a longing for peace from the constant public gaze that had defined much of his life.

His statement, “‘I’m tired of being on a tour bus route. Every time we would leave our house, the tour bus would be going by and would follow us’,” vividly illustrates the relentless nature of his celebrity. This constant surveillance, even at his home, fueled his desire to avoid becoming a posthumous tourist attraction, ensuring that his final resting place would not become another site for public curiosity.

The phrase “‘For me it’s dust to dust’,” encapsulates his philosophical approach to mortality, suggesting a preference for a natural, unostentatious end. He conveyed that “he didn’t need to have a big memorial somewhere,” indicating a profound understanding and acceptance of the ephemeral nature of physical existence, and a rejection of elaborate posthumous tributes.

Patricia Ward Kelly profoundly understood and respected this perspective. She noted that “some people think they have to go someplace, but for me he’s just always here, so I don’t need to go to a particular spot to mourn him.” This shared understanding speaks to the deep spiritual connection they held, one that transcended physical locations and traditional mourning rituals. Kelly was, in her words, “very thoughtful” about these arrangements.

His foresight was also shaped by observing the experiences of his friends. “I think what helped him was experiencing the death of so many of his friends. He saw what happened to them, so it also helped to guide his choices.” Having “sat through a lot of memorial services and visited a lot of gravesites,” he gained clarity on what he wanted for himself, choosing a path that honored his desire for quiet dignity and personal meaning.

7. **From Pittsburgh to Broadway: The Genesis of a Dance Icon**

Eugene Curran Kelly’s journey into the world of dance and entertainment began not with an immediate passion but through his mother’s initiative. Born in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh on August 23, 1912, as the middle of five children, Kelly’s early introduction to dance came at the tender age of eight when his mother enrolled him and his brother James, alongside their sisters, in dance classes. This initial foray was met with typical boyish resistance, as Kelly recalled, “We didn’t like it much and were continually involved in fistfights with the neighborhood boys who called us sissies … I didn’t dance again until I was 15.”

Despite this early aversion, Kelly’s athletic inclinations flourished, allowing him to defend himself by the time he decided to return to dance. His childhood dream, surprisingly, was to become a shortstop for the hometown Pittsburgh Pirates. He attended St. Raphael Elementary School and graduated from Peabody High School at 16. The economic upheaval of the 1929 crash prompted him to leave Pennsylvania State College, where he was a journalism major, to help support his family, leading him and his younger brother Fred to create dance routines for prize money in local talent contests and performances in nightclubs.

In 1931, Kelly enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh to study economics, actively participating in the university’s Cap and Gown Club, which produced original musical productions. After graduating in 1933, he continued his involvement, directing the club from 1934 to 1938. He even began law school at the University of Pittsburgh, indicating a diverse range of intellectual pursuits beyond the performing arts.

Simultaneously, his family established a dance studio in Pittsburgh, later expanding it and renaming it the Gene Kelly Studio of the Dance. Kelly served as a teacher during his undergraduate and law-student years. His talents extended to teaching at the Beth Shalom Synagogue, where he taught dance and staged their annual Kermesse for seven successful years, until his eventual departure for New York.

Eventually, the allure of dance and entertainment became undeniable, leading him to drop out of law school after only two months. His initial focus was on teaching, but he soon became “disenchanted with teaching because the ratio of girls to boys was more than ten to one, and once the girls reached 16, the dropout rate was very high.” This pragmatic realization, combined with his growing performing ambitions, propelled him to New York City in 1937, seeking work as a choreographer. A brief return to his family home in Pittsburgh in 1940 saw him working as a theatrical actor before his Broadway career truly began to take flight.

Having explored the personal landscape of Gene Kelly’s later life and the formative experiences of his youth, we now turn our gaze to the monumental ascent of his professional career. From the vibrant stages of Broadway to the glittering soundstages of Hollywood, Kelly’s journey was one of relentless innovation, shaping the very language of musical film and leaving an indelible mark on the art of dance.

8. **Broadway’s Call: Kelly’s Stage Breakthroughs**

Gene Kelly’s professional dance career, while rooted in his family’s Pittsburgh studio and local performances, truly began its trajectory with his bold move to New York City in 1937, initially seeking work as a choreographer. However, a brief return to Pittsburgh in 1940 saw him hone his skills as a theatrical actor before the lights of Broadway definitively called. His first significant position as a choreographer came in April 1938 for the Charles Gaynor musical revue, ‘Hold Your Hats,’ at the Pittsburgh Playhouse, where he also appeared in six sketches, one of which would later inspire a celebrated Spanish number in ‘Anchors Aweigh.’

His Broadway debut arrived in November 1938 as a dancer in Cole Porter’s ‘Leave It to Me!’ Here, he played the American ambassador’s secretary, supporting Mary Martin as she famously sang ‘My Heart Belongs to Daddy.’ This role was secured thanks to Robert Alton, who had been impressed by Kelly’s teaching abilities at the Pittsburgh Playhouse. Alton would again hire Kelly for the musical ‘One for the Money,’ where he showcased his versatility by acting, singing, and dancing in eight different routines. This early recognition by industry veterans underscored his burgeoning talent and work ethic.

The year 1939 marked a pivotal period for Kelly. He secured his first assignment as a Broadway choreographer for Billy Rose’s ‘Diamond Horseshoe,’ but it was his lead role in ‘The Time of Your Life’ that truly provided his first major breakthrough on Broadway, allowing him to dance to his own choreography for the first time on that illustrious stage. This success was swiftly followed in 1940 by the lead role in Rodgers and Hart’s ‘Pal Joey,’ a performance choreographed once more by Robert Alton, which solidified his status as a rising star and propelled him into the public consciousness.

During the successful run of ‘Pal Joey,’ Kelly articulated his distinctive approach to dance, stating, “I don’t believe in conformity to any school of dancing. I create what the drama and the music demand.” He emphasized a pragmatic integration of techniques, noting, “While I am a hundred percent for ballet technique, I use only what I can adapt to my own use. I never let technique get in the way of mood or continuity.” His colleagues, including Van Johnson, marveled at his commitment, recalling Kelly’s tireless rehearsals long after others had departed, a testament to his profound dedication to his craft.

9. **Hollywood Beckons: Establishing a Film Presence**

The undeniable talent displayed on the Broadway stage soon caught the attention of Hollywood. Offers began to pour in, but Kelly, ever deliberate, was in no rush to leave New York. He eventually signed with David O. Selznick, with an agreement to transition to Hollywood after his commitment to ‘Pal Joey’ concluded in October 1941. Before making the move, he also managed to choreograph the stage production of ‘Best Foot Forward,’ further demonstrating his versatile skills.

Selznick’s initial vision saw Kelly’s contract partially sold to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, leading to his motion picture debut in ‘For Me and My Gal’ (1942) alongside Judy Garland. Kelly candidly recalled his initial reaction to seeing himself on the big screen: “I was appalled at the sight of myself blown up 20 times. I had an awful feeling that I was a tremendous flop.” Despite his personal apprehension, the film performed exceptionally well, prompting Arthur Freed of MGM to acquire the remaining half of Kelly’s contract, recognizing his undeniable star potential against initial internal resistance.

His early film career at MGM included diverse roles, from a B-movie drama ‘Pilot No. 5’ (1943) where he unusually played the antagonist, to ‘Christmas Holiday’ (1944) and a male lead in Cole Porter’s ‘Du Barry Was a Lady’ (1943) opposite Lucille Ball. His first opportunity to choreograph his own dance sequence on film arrived in ‘Thousands Cheer’ (1943), where he charmingly performed a mock-love dance with a mop, a glimpse into the innovative movement to come.

A significant breakthrough for Kelly as a film dancer occurred in 1944 when MGM lent him to Columbia. This collaboration with Rita Hayworth in ‘Cover Girl’ (1944) proved prophetic, foreshadowing the depth of his future work. He devised a memorable routine dancing with his own reflection, yet initial critical reception, such as that from Manny Farber, praised his acting ‘attitude’ and ‘feeling’ while inauspiciously concluding that ‘singing and dancing’ were his least effective skills.

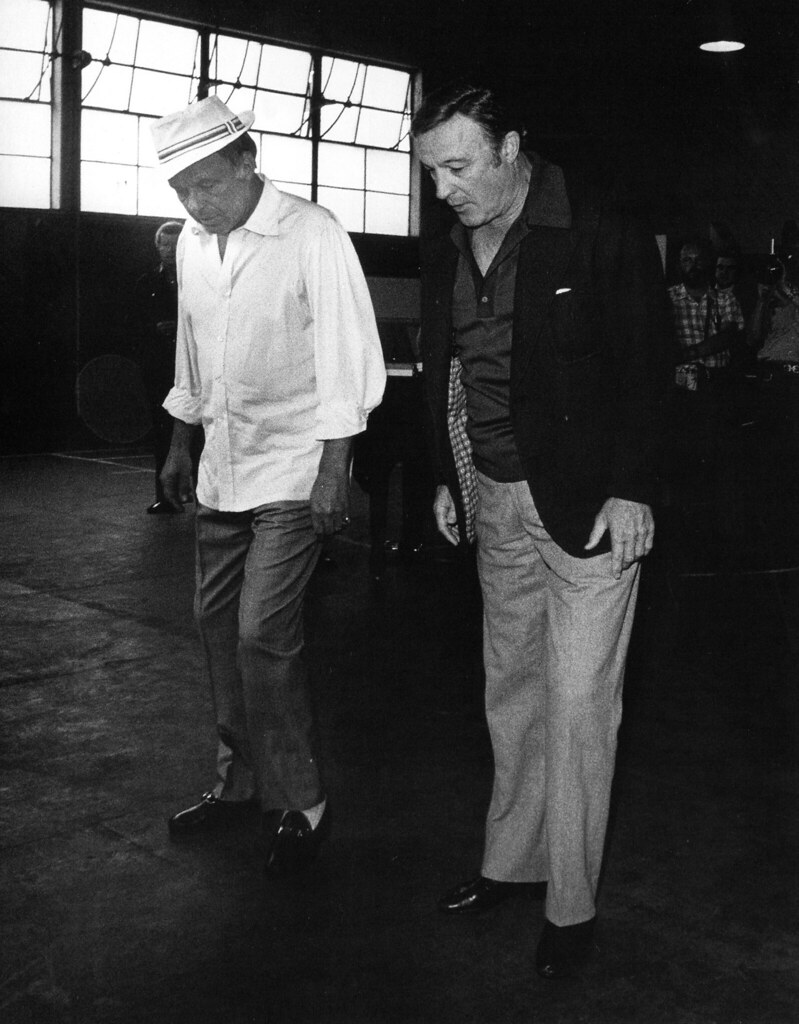

However, the very next year, ‘Anchors Aweigh’ (1945), afforded Kelly extensive creative freedom from MGM to develop a range of dance routines. This film featured his iconic duets with co-star Frank Sinatra and, most famously, the groundbreaking animated dance with Jerry Mouse, with animation supervised by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera. This performance led critic Manny Farber to completely reverse his earlier assessment, effusively declaring Kelly “the most exciting dancer to appear in Hollywood movies.” ‘Anchors Aweigh’ was a major success, earning Kelly a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor. His talents were further showcased in ‘Ziegfeld Follies’ (1946), where he collaborated with the legendary Fred Astaire, for whom he held the highest admiration, in the “The Babbitt and the Bromide” challenge dance routine.

10. **Military Service and a Redefined Artistic Perspective**

As the world was embroiled in conflict, Gene Kelly, like many men of his generation, faced the call to service. Initially deferred from the draft in 1940 at the request of his employers, his eligibility shifted, and he was ultimately classified 1-A, making him eligible for induction in October 1944. This reclassification occurred after an appeal to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt by the head of the Selective Service in New York City, which Roosevelt personally upheld.

In November 1944, Kelly was formally inducted into the armed forces. Responding to his request, he was assigned to the U.S. Navy. His service led him to the U.S. Naval Air Service, where he was commissioned as a lieutenant, junior grade. He was stationed in the Photographic Section in Washington, D.C., a posting that proved to be unexpectedly formative for his artistic journey.

During his time in Washington, Kelly actively contributed to the war effort by helping to write and direct a variety of documentaries. This hands-on experience in the production side of filmmaking proved to be a significant turning point, stimulating a keen interest in the technical and directorial aspects of the medium that would profoundly influence his later career. He was honorably discharged in 1946, returning to Hollywood with not only a distinguished service record but also a broadened understanding of the craft he would soon revolutionize.

11. **MGM’s Golden Era: Choreographic Innovation and Musical Mastery**

Upon Gene Kelly’s return from Naval service, MGM initially had no immediate plans for him, assigning him to a routine black-and-white movie, ‘Living in a Big Way’ (1947). Recognizing its inherent weaknesses, the studio requested Kelly to design and integrate a series of dance routines, an assignment that highlighted his exceptional ability to craft and execute such sequences. This demonstration of his choreographic prowess directly led to his next significant role.

His subsequent project was a lead part in ‘The Pirate’ (1948), a musical film version of S.N. Behrman’s play, directed by Vincente Minnelli and co-starring Judy Garland, featuring songs by Cole Porter. ‘The Pirate’ provided a full canvas for Kelly’s athletic and dynamic style, notably showcasing his virtuosic work with the Nicholas Brothers, who were among the foremost Black dancers of their era. Though now revered as a classic for its innovative choreography and daring spirit, the film was considered ahead of its time and did not perform well at the box office.

Despite the critical acclaim for ‘The Pirate,’ MGM sought to steer Kelly back towards more commercially safe projects. Yet, Kelly tirelessly advocated for the opportunity to direct his own musical films. In the interim, he capitalized on his swashbuckling persona, portraying d’Artagnan in ‘The Three Musketeers’ (1948) and appearing with Vera-Ellen in the ‘Slaughter on Tenth Avenue’ ballet sequence in ‘Words and Music’ (1948). A notable setback occurred when he broke his ankle playing volleyball, forcing him to withdraw from ‘Easter Parade’ (1948), a role for which he successfully persuaded Fred Astaire to come out of retirement as his replacement.

The year 1949 proved instrumental in reshaping Kelly’s trajectory. He starred in ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game,’ his second film with Frank Sinatra, where he paid a heartfelt tribute to his Irish heritage in “The Hat My Father Wore on St. Patrick’s Day” routine. The success of this musical convinced Arthur Freed to greenlight ‘On the Town’ (1949), marking his third and final cinematic pairing with Frank Sinatra. This film was a groundbreaking achievement in the musical genre, hailed as “the most inventive and effervescent musical thus far produced in Hollywood.”

For ‘On the Town,’ Stanley Donen, whom Kelly had brought to Hollywood as his assistant choreographer, received co-director credit. Kelly acknowledged this collaboration, explaining that “when you are involved in doing choreography for film, you must have expert assistants,” emphasizing their evolving partnership as “co-creators.” Together, Kelly and Donen revolutionized the musical form, famously taking the film musical out of the confines of the studio and onto real locations. Donen focused on staging, while Kelly concentrated on choreography, incorporating modern ballet into his dance sequences more extensively than ever before, even utilizing leading ballet specialists for the “Day in New York” routine. Following this, Kelly sought a straight acting role, taking the lead in the early Mafia melodrama ‘Black Hand’ (1950), an exposé set in New York’s “Little Italy” that carefully navigated the sensitivities of depicting organized crime by focusing on a ‘dead’ criminal organization.

Next came ‘Summer Stock’ (1950), Judy Garland’s final musical film for MGM. In this feature, Kelly delivered a memorable solo routine titled “You, You Wonderful You,” ingeniously performed with only a newspaper and a squeaky floorboard. Joe Pasternak, head of one of MGM’s musical units, lauded Kelly for his exceptional patience and willingness to dedicate ample time to support the ailing Garland in completing her part, showcasing his professionalism and compassion.

In rapid succession, two musicals followed that would definitively cement Gene Kelly’s reputation as a towering figure in the American musical film: ‘An American in Paris’ (1951) and ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ (1952). As co-director, lead star, and choreographer, Kelly was the indisputable driving force behind both of these iconic films. Johnny Green, then head of music at MGM, attested to Kelly’s formidable dedication and unwavering artistic vision: “He’s a hard taskmaster and he loves hard work… He isn’t cruel, but he is tough, and if Gene believed in something, he didn’t care who he was talking to… He wasn’t awed by anybody, and he had a good record of getting what he wanted.”

‘An American in Paris’ was a monumental success, garnering six Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The film also marked the auspicious debut of 19-year-old ballerina Leslie Caron, whom Kelly had discovered in Paris and brought to Hollywood. Its celebrated dream ballet sequence, a breathtaking 17-minute spectacle, set a new benchmark as the most expensive production number ever filmed at that time, described by Bosley Crowther as “whoop-de-doo … one of the finest ever put on the screen.” In 1951, Kelly himself received an honorary Academy Award, acknowledging his profound contributions to film musicals and the art of choreography.

The subsequent year brought ‘Singin’ in the Rain,’ a film now universally acclaimed and featuring Kelly’s celebrated and frequently emulated solo dance routine to the iconic title song. This masterpiece also included the dynamic “Moses Supposes” routine with Donald O’Connor and the dazzling “Broadway Melody” finale, which showcased the elegant Cyd Charisse. While ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ did not initially ignite the same fervent enthusiasm as ‘An American in Paris,’ it has since surpassed its predecessor to attain its current pre-eminent status in the estimation of critics and audiences worldwide, solidifying its place as arguably the greatest film musical ever made.

12. **Navigating the Changing Tides: The Decline of Hollywood Musicals**

At the zenith of his creative powers, Gene Kelly made a strategic move that, in retrospect, some observers viewed as a career misstep. In December 1951, he signed a unique contract with MGM that allowed him to work in Europe for 19 months. The arrangement was designed to utilize MGM funds frozen abroad, enabling him to make three pictures while personally benefiting from significant tax exemptions. The first of these, ‘Invitation to the Dance,’ was a deeply personal passion project for Kelly, aimed at introducing modern ballet to a mainstream film audience. However, it was plagued by extensive delays and numerous technical problems, ultimately flopping commercially upon its release in 1956.

By the time Kelly returned to Hollywood in 1953, the landscape of film entertainment was rapidly shifting. The rise of television began to exert significant pressure on the traditional film musical. Reflecting these changing times, MGM drastically cut the budget for his next picture, ‘Brigadoon’ (1954), starring Cyd Charisse. This constraint forced Kelly to film the production entirely on studio backlots rather than the intended authentic locations in Scotland, altering its original vision. That same year, he also appeared as a guest star alongside his brother Fred in the lighthearted “I Love to Go Swimmin’ with Wimmen” routine in ‘Deep in My Heart’ (1954).

Further strains developed in Kelly’s relationship with the studio when MGM refused to lend him out for starring roles in other highly anticipated musicals like ‘Guys and Dolls’ and ‘Pal Joey.’ This ongoing friction eventually led him to negotiate an exit from his contract, a process that entailed making three additional pictures for MGM. The first of these, ‘It’s Always Fair Weather’ (1955), co-directed with Stanley Donen, was a satirical musical that shrewdly commented on the burgeoning influences of television and advertising. This film memorably featured his innovative roller-skate dance routine set to “I Like Myself,” and a dynamic dance trio with Michael Kidd and Dan Dailey, through which Kelly experimented with the expansive possibilities of Cinemascope widescreen.

By this point, MGM had seemingly lost confidence in Kelly’s drawing power at the box office, a sentiment perhaps influenced by the commercial struggles of ‘Invitation to the Dance.’ Consequently, ‘It’s Always Fair Weather’ premiered in a rather unconventional manner, opening at 17 drive-in theaters across the Los Angeles metropolitan area. His final musical film for MGM was ‘Les Girls’ (1957), where he shared the screen with Mitzi Gaynor, Kay Kendall, and Taina Elg. The third picture completed under his revised contract was ‘The Happy Road’ (1957), a B-film set in his cherished France, which marked a new chapter for Kelly as his first venture in the triple role of producer, director, and actor. After fulfilling his obligations and departing from MGM, Kelly strategically returned to stage work, seeking new artistic avenues.

13. **Beyond the Spotlight: Directorial Ventures and Television Presence**

After his departure from MGM, Gene Kelly continued to innovate, turning his talents to directing both on stage and screen. In 1958, he directed Rodgers and Hammerstein’s acclaimed musical play ‘Flower Drum Song.’ His deep affinity for French culture and fluency in the language led to a unique invitation in early 1960 from A. M. Julien, the general administrator of the Paris Opéra and Opéra-Comique. This unprecedented opportunity allowed Kelly, as the first American to receive such an assignment, to select his own material and create a modern ballet for the esteemed company. The result was ‘Pas de Dieux,’ a ballet based on Greek mythology set to the music of George Gershwin’s ‘Concerto in F,’ which enjoyed major success and earned him the prestigious Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur from the French Government.

While increasingly focused on production and directing, Kelly continued to make select film appearances in the 1960s, notably as Hornbeck in the Hollywood production of ‘Inherit the Wind’ (1960) and as himself in ‘Let’s Make Love.’ His directorial efforts during this period included ‘Gigot’ (1962), starring Jackie Gleason, which, unfortunately, was drastically re-cut by Seven Arts Productions and subsequently flopped. Another significant French venture was Jacques Demy’s ‘The Young Girls of Rochefort’ (Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, 1967), a musical homage to the MGM style, in which Kelly also appeared. While it was a box-office success in France and garnered Academy Award nominations for Best Music and Score, its performance in other markets was less robust.

Intriguingly, Kelly was approached to direct the 1965 film adaptation of ‘The Sound of Music’ but famously declined, having little affinity for the project. He reportedly escorted screenwriter Ernest Lehman from his home with a candid dismissal, “Go find someone else to direct this piece of shit,” underscoring his discerning taste and willingness to reject projects that did not align with his artistic vision.

Kelly’s foray into television proved equally innovative, beginning with a documentary for NBC’s ‘Omnibus’ titled ‘Dancing is a Man’s Game’ (1958). In this groundbreaking program, he brought together an extraordinary group of America’s greatest sportsmen, including Mickey Mantle, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Bob Cousy. Kelly then choreographically reinterpreted their athletic movements, part of his lifelong mission to dismantle the effeminate stereotype often associated with dance, while simultaneously articulating the philosophical underpinnings of his own dynamic dance style. The special earned an Emmy nomination for choreography and remains a crucial document illustrating Kelly’s progressive approach to modern dance.

Throughout the 1960s, Kelly was a frequent presence on television, including a starring role in the series ‘Going My Way’ (1962–63), based on the popular 1944 film, which enjoyed considerable popularity in Roman Catholic countries outside the United States. He also graced three major TV specials: ‘The Julie Andrews Show’ (1965), ‘New York, New York’ (1966), and ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’ (1967). The latter, a show he personally produced and directed, skillfully combined cartoon animation with live dance, earning him an Emmy Award for Outstanding Children’s Program, a testament to his enduring creativity and ability to blend various art forms.

After joining Universal Pictures for a two-year period in 1963 and then 20th Century Fox in 1965, Kelly’s opportunities were somewhat limited, partly due to his decision to decline assignments that would take him away from Los Angeles for family reasons. However, his perseverance ultimately bore fruit with the significant box-office success of ‘A Guide for the Married Man’ (1967), which he directed, starring Walter Matthau. A major opportunity then emerged when Fox, encouraged by the substantial returns from ‘The Sound of Music’ (1965), commissioned Kelly to direct ‘Hello, Dolly!’ (1969), once again directing Matthau, this time alongside the formidable Barbra Streisand. The film earned seven Academy Award nominations, winning three.

In 1966, Kelly also starred in a captivating musical television special for CBS titled ‘Gene Kelly in New York, New York.’ This program featured Kelly in a musical odyssey across Manhattan, dancing against iconic backdrops such as Rockefeller Center, the Plaza Hotel, and the Museum of Modern Art, which served as vibrant settings for the show’s entertaining production numbers. The special was notably written by Woody Allen, who also co-starred with Kelly, and featured guest appearances by choreographer Gower Champion, British musical comedy star Tommy Steele, and singer Damita Jo DeBlanc, showcasing a dynamic fusion of talent.

The 1970s saw Kelly continue his television work with another special, ‘Gene Kelly and 50 Girls.’ He was subsequently invited to bring this show to Las Vegas, accepting on the condition that he would be compensated more than any artist had ever received there, a testament to his negotiating power. He directed veteran actors James Stewart and Henry Fonda in the comedy Western ‘The Cheyenne Social Club’ (1970), which unfortunately performed poorly at the box office. In 1973, he reunited with Frank Sinatra for Sinatra’s Emmy-nominated TV special, ‘Magnavox Presents Frank Sinatra,’ rekindling their cinematic partnership.

A highlight of this decade was his appearance in 1974 as one of many special narrators in the surprise hit ‘That’s Entertainment!’ This led to a sequel, ‘That’s Entertainment, Part II’ (1976), which Kelly directed and co-starred in with his dear friend Fred Astaire. It was a remarkable demonstration of Kelly’s powers of persuasion that he managed to coax the 77-year-old Astaire, who had long since retired and explicitly stipulated no dancing in his contract, into performing a series of nostalgic song-and-dance duets, evoking the golden era of the American musical film.

14. **A Lasting Legacy: Final Roles and Enduring Influence** Gene Kelly’s later career included continued television appearances and a few notable film roles. He was a guest on the 1975 television special ‘Our Love Is Here to Stay,’ starring Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gormé, where he appeared with his son, Tim, and daughter, Bridget. He then starred in the poorly received action film ‘Viva Knievel!’ (1977), alongside the high-profile stuntman Evel Knievel. His final film role was in ‘Xanadu’ (1980), a musical fantasy that, despite its popular soundtrack yielding five Top 20 hits by Electric Light Orchestra, Cliff Richard, and co-star Olivia Newton-John, ultimately proved to be a commercial flop. Kelly himself reflected on it, stating, “The concept was marvelous, but it just didn’t come off.”

Gene Kelly’s later career included continued television appearances and a few notable film roles. He was a guest on the 1975 television special ‘Our Love Is Here to Stay,’ starring Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gormé, where he appeared with his son, Tim, and daughter, Bridget. He then starred in the poorly received action film ‘Viva Knievel!’ (1977), alongside the high-profile stuntman Evel Knievel. His final film role was in ‘Xanadu’ (1980), a musical fantasy that, despite its popular soundtrack yielding five Top 20 hits by Electric Light Orchestra, Cliff Richard, and co-star Olivia Newton-John, ultimately proved to be a commercial flop. Kelly himself reflected on it, stating, “The concept was marvelous, but it just didn’t come off.”

In 1980, Kelly was invited by Francis Ford Coppola to assemble a production staff for American Zoetrope’s ‘One from the Heart’ (1982). While Coppola harbored ambitions for Kelly to establish a production unit that could rival MGM’s legendary Freed Unit, the film’s commercial failure ultimately put an end to this grand vision. In November 1983, Kelly made his first Royal Variety Performance before Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II at London’s Theatre Royal, a testament to his enduring international appeal.

Kelly also served as executive producer and co-host of ‘That’s Dancing!’ (1985), a celebratory retrospective on the history of dance within the American musical. His final on-screen appearance was to introduce ‘That’s Entertainment! III’ (1994), bringing his cinematic journey full circle. Though not released until 1997, after his passing, his final film project was the animated film ‘Cats Don’t Dance,’ for which Kelly contributed as an uncredited choreographic consultant. The film was dedicated to his memory, a fitting tribute to his lifelong passion. A lesser-known anecdote from his final years involved a brief engagement in 1993 with Madonna and her brother Christopher Ciccone to choreograph part of Madonna’s ‘The Girlie Show’ tour; however, differing artistic visions regarding the performers and their dancing abilities led to his swift dismissal.

Gene Kelly’s profound influence on filmed dance stemmed from his unique working methods and a clear vision. He was significantly shaped by the influences of Robert Alton and John Murray Anderson, and his choreographic work, for both his own movements and those of the ensemble, was meticulously crafted with the indispensable assistance of Jeanne Coyne, Stanley Donen, Carol Haney, and Alex Romero. Kelly relentlessly experimented with camera techniques, lighting, and special effects, always striving for a true, organic integration of dance with the cinematic medium. He was a pioneer in utilizing split screens, double images, and live action alongside animation, and is widely credited with almost single-handedly making the ballet form commercially acceptable to broader film audiences.

His artistic development showed a clear evolution, moving from an early emphasis on tap and musical comedy styles towards a greater complexity that embraced ballet and modern dance forms. Kelly, however, resisted categorizing his own style, describing it as “hybrid.” He explained, “I’ve borrowed from the modern dance, from the classical, and certainly from the American folk dance—tap-dancing, jitterbugging … But I have tried to develop a style which is indigenous to the environment in which I was reared.” He particularly acknowledged the strong influence of George M. Cohan, attributing “an Irish quality, a jaw-jutting, up-on-the-toes cockiness—which is a good quality for a male dancer to have” to Cohan.

Kelly’s dance influences were diverse and profound. He was deeply affected by an African-American dancer named Robert Dotson, whose performance at Loew’s Penn Theatre around 1929 left a lasting impression. He also received brief instruction from Frank Harrington, an African-American tap specialist from New York. However, his primary interest remained in ballet, which he rigorously studied under Kotchetovsky in the early 1930s. Additionally, he studied Spanish dancing under Angel Cansino, who was Rita Hayworth’s uncle, demonstrating his wide-ranging pursuit of dance forms. Generally, he utilized tap and other popular dance idioms to convey joy and exuberance, evident in the title song for ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ or “I Got Rhythm” in ‘An American in Paris.’ Conversely, more introspective or romantic emotions were often expressed through ballet or modern dance, as beautifully illustrated in “Heather on the Hill” from ‘Brigadoon’ or “Our Love Is Here to Stay” from ‘An American in Paris.’

According to dance and art historian Beth Genné, Kelly, in collaboration with his co-director Donen in ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ and with director Vincente Minnelli in other films, “fundamentally affected the way movies are made and the way we look at them. And he did it with a dancer’s eye and from a dancer’s perspective.” Delamater further suggests that Kelly’s work “seems to represent the fulfillment of dance–film integration in the 1940s and 1950s.” While Fred Astaire had revolutionized the filming of dance in the 1930s by insisting on full-figure photography with limited camera movement, Kelly took a bolder approach.

Kelly significantly liberated the camera, making more extensive use of space, dynamic camera movement, varied angles, and intricate editing. This approach forged a symbiotic partnership between the dance movement and the camera’s movement, all while meticulously preserving full-figure framing of the dancers. His rationale was that the raw kinetic force of live dance often dissipated when transferred to film. He sought to counteract this by involving the camera in the movement itself and by providing the dancer with a greater array of directions in which to move, thereby enhancing the cinematic experience of dance.

This innovative philosophy is vividly demonstrated throughout Kelly’s body of work, with prime examples including the energetic “Prehistoric Man” sequence from ‘On the Town’ and the spirited “The Hat My Father Wore on St. Patrick’s Day” from ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game.’ Kelly succinctly encapsulated his vision in 1951: “If the camera is to make a contribution at all to dance, this must be to move with the dance, not simply observe it.” His legacy, therefore, is not merely that of a performer but of a visionary who profoundly re-imagined the relationship between dance and cinema, ensuring that his athletic, expressive art would forever resonate with audiences.

In reflecting upon the extraordinary life of Gene Kelly, from his humble beginnings in Pittsburgh to his global renown as a cinematic icon, we witness a journey defined by relentless artistic curiosity, unwavering dedication, and a profound desire to elevate dance to an accessible art form for all. His story is one of innovation and grace, a testament to a man who danced not just for the camera but for the common man, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and entertain, far beyond the final curtain call.