For decades, the gangster film genre has captivated audiences, offering glimpses into a world of power, loyalty, and violence. Yet, amidst the classic narratives that have defined our understanding, there emerges a singular cinematic achievement that dares to pull back the curtain even further, revealing a truth so stark and unglamorous it implicitly challenges the very foundations of how we perceive the mob. Martin Scorsese’s 1990 masterpiece, *Goodfellas*, is not just another entry in the pantheon of crime films; it’s a seismic shift, an unflinching exposé that lays bare the mundane brutality and often absurd reality of life within the Mafia, forcing us to confront a narrative far removed from the operatic grandeur we might have come to expect.

This isn’t merely a critique of what came before, but an invitation to re-examine our collective understanding of organized crime through a different, often uncomfortable, lens. As we journey through the meticulously crafted world of Henry Hill, Jimmy Conway, and Tommy DeVito, *Goodfellas* doesn’t just tell a story; it immerses us in a lifestyle, showing us “the day-to-day life, the tedium, how they work, how they take over certain nightclubs, and for what reasons. It shows how it’s done.” It’s a film that, through its raw honesty and relentless pace, arguably highlights a certain romanticization in other, equally revered, mob sagas – a romanticization that *Goodfellas* actively dismantles with every quick cut, every improvised line, and every chilling act of violence.

What *Goodfellas* ultimately achieves is a profound redefinition of the gangster narrative, offering a perspective so grounded in gritty realism that it becomes a benchmark for authenticity. It’s a film that isn’t afraid to be “funny and brutal and it felt very real,” as director David Chase himself noted in contrasting it with the more “operatic, classical” feel of *The Godfather*. This article will delve into the foundational elements of *Goodfellas* that allowed it to accomplish this, exploring how Scorsese and his team meticulously constructed a vision that continues to resonate and provoke discussion about the true nature of the criminal underworld.

1. **Scorsese’s Vision: The Pursuit of the “Most Honest Portrayal”**Martin Scorsese’s journey to *Goodfellas* began not with an ambition to revisit the Mafia genre, but with a profound connection to Nicholas Pileggi’s 1985 nonfiction book, *Wiseguy*. Scorsese, who had “always been fascinated by the mob lifestyle,” read a review of Pileggi’s book while working on *The Color of Money* in 1986. What captivated him was a perceived level of truth he hadn’t encountered before. He found it to be “the most honest portrayal of gangsters that he had ever read,” a statement that immediately signals his intent for the film.

This isn’t just a director picking a story; it’s an artist finding the perfect vehicle for a vision rooted in authenticity. Scorsese’s enthusiasm was palpable, reportedly telling Pileggi, “I’ve been waiting for this book my entire life.” This long-held desire to depict the mob without veneer, stripping away any lingering romanticism, became the driving force behind the project. He sought to capture the essence of what truly drew individuals to such a life, and what kept them tethered to its dangers.

His approach was clear from the outset: “To begin Goodfellas like a gunshot and have it get faster from there, almost like a two-and-a-half-hour trailer. I think it’s the only way you can really sense the exhilaration of the lifestyle, and to get a sense of why a lot of people are attracted to it.” This wasn’t about slow-burn character development in the traditional sense, but an immediate, visceral plunge into the high-octane, unpredictable world of a wiseguy. It was a stylistic choice inherently designed to mimic the rush and the rapid-fire succession of events in Henry Hill’s life, immersing the audience in the chaotic reality rather than allowing for detached observation.

The documentary aspects of Pileggi’s book particularly appealed to Scorsese. He recognized that the book offered “a sense of the day-to-day life, the tedium, how they work, how they take over certain nightclubs, and for what reasons. It shows how it’s done.” This granular detail, the nitty-gritty of criminal enterprise beyond the dramatic hits and power plays, was crucial to his vision. It aimed to show the mechanics, the logistics, and the sheer graft involved, grounding the narrative in a tangible reality that was rarely explored with such candidness. This commitment to portraying the ordinary alongside the extraordinary truly set the stage for *Goodfellas* to offer its unique, unvarnished perspective.

2. **The “Mob Home Movie” Aesthetic: Unpacking Money and Reality**Scorsese famously described *Goodfellas* as “a mob home movie” that is fundamentally “about money, because ‘that’s what they’re really in business for’.” This simple, yet profoundly insightful characterization, cuts to the core of the film’s unique realism. It dismantles any romantic notions of honor or grand criminal empires, instead boiling down the mob’s existence to its most basic, transactional element: profit. This perspective is a crucial counterpoint to more mythologized portrayals, emphasizing the business aspect rather than moral codes or familial loyalty as the ultimate driver.

By framing it as a “home movie,” Scorsese implies an intimate, almost voyeuristic glimpse into the lives of these men and their families, seen through a less formal, more immediate lens. It’s not a curated epic; it’s raw footage, a collection of candid moments that expose the mundane alongside the violent. This aesthetic choice aligns perfectly with the film’s ambition to be the “most honest portrayal,” because home movies, by their nature, aim to capture life as it truly is, imperfections and all, without the polished veneer of a cinematic production.

Indeed, the narrative often focuses on the practicalities of illegal enterprise, from carjacking to stealing cargo trucks from JFK Airport, culminating in the ambitious Lufthansa vault heist. These aren’t just plot points; they are demonstrations of “how it’s done,” underscoring the mob’s relentless pursuit of illicit gains. The characters aren’t driven by abstract ideals; they are motivated by the tangible rewards—the expensive items, the glamorous nights at the Copacabana, the lavish lifestyles that seduce even Karen Friedman.

The film constantly reminds us that this high-rolling existence, however intoxicating, is built on a foundation of precarious financial maneuvering. When Karen is forced to flush $60,000 worth of cocaine down the toilet, leaving the Hills “penniless,” the stark reality of their financial vulnerability is laid bare. Paulie’s decision to give Henry $3,200 and end their association highlights the transactional nature of their relationships, where loyalty is often secondary to liability and profitability. This focus on the practical, often messy, economics of crime reinforces the “home movie” feel, showing the financial ups and downs that are rarely given such detailed attention in the genre.

3. **Breaking Narrative Chains: New Wave Influence and Revolutionary Structure**One of the most radical aspects of *Goodfellas*, and a key element in its realistic impact, is Scorsese’s deliberate rejection of traditional narrative structure. He and Nicholas Pileggi, in their collaboration on the screenplay, actively chose to discard conventional storytelling arcs. As Pileggi realized, “the visual styling had to be completely redone,” and they decided to “share credit” on the script that went through 12 drafts. Scorsese persuaded Pileggi that a traditional narrative was unnecessary for the story they wanted to tell.

Scorsese wanted to “take the gangster film and deal with it episode by episode, but start in the middle and move backward and forward.” This non-linear, episodic approach mirrored the chaotic, unpredictable flow of real life, particularly a criminal one. It prevents the audience from settling into a comfortable, predictable rhythm, much like the characters themselves could never truly relax. By compacting scenes and keeping them short, Scorsese believed that “the impact after about an hour and a half would be terrific,” creating a relentless pace that mirrors the exhilarating, yet ultimately exhausting, nature of the wiseguy lifestyle.

The influence of the French New Wave is explicitly acknowledged by Scorsese. He aimed to use narration “in a manner reminiscent of François Truffaut’s 1962 film *Jules and Jim*, and use ‘all the basic tricks of the New Wave from around 1961’.” This included extensive narration, quick edits, freeze frames, and multiple locale switches. This “reckless attitude toward convention” was not just a stylistic flourish; it was integral to the film’s thematic core, mirroring the “punk attitude” of the gangsters themselves.

This frenetic style was intended to “almost overwhelm the audience with images and information,” reflecting the sensory overload of Henry’s life. Freeze frames, for example, were employed to highlight that “a point was being reached” in Henry’s journey, drawing attention to pivotal moments without traditional exposition. The rapid cuts and constant shifts in perspective immerse the viewer in the ceaseless activity and paranoia that define the characters’ existence, fostering a visceral understanding of their reality rather than a detached narrative observation. This innovative structure ensures that *Goodfellas* isn’t just a story told, but an experience lived, demanding constant engagement from its audience.

4. **Immersive Actor Preparation: Crafting Authentic Characters Through Dedication**The unassailable authenticity of *Goodfellas* is not solely a product of Scorsese’s direction or the groundbreaking script; it is profoundly rooted in the extraordinary dedication of its cast to inhabit their roles with unflinching realism. Robert De Niro, playing Jimmy Conway, embarked on a meticulous research process, consulting with Nicholas Pileggi. Pileggi, having accumulated a wealth of discarded research material from writing *Wiseguy*, shared these insights with De Niro, allowing him to delve deeper into the nuances of the real-life Jimmy “The Gent” Burke.

De Niro’s commitment extended to even the smallest physical details, as he would “often call Hill several times a day to ask how Burke walked, held his cigarette, and so on.” This level of granular preparation ensured that his portrayal was not merely an interpretation but a faithful recreation, lending an almost documentary-like quality to his performance. Such dedication to physical authenticity grounds the character in a tangible reality, making Jimmy Conway a figure of terrifying verisimilitude on screen.

Ray Liotta, cast as Henry Hill, immersed himself in his character’s real-life counterpart with equal intensity. Having read Pileggi’s book and been fascinated by it, Liotta vigorously campaigned for the role, despite Warner Bros.’ initial preference for a more well-known actor. Once cast, his preparation involved a deep dive into Hill’s actual voice and mannerisms. “Driving to and from the set, Liotta listened to FBI audio cassette tapes of Hill, so that he could practice speaking like his real-life counterpart.”

This auditory immersion allowed Liotta to capture the distinct vocal patterns and inflections of Henry Hill, adding another layer of authenticity to his performance. The meticulousness of his preparation prevented any caricature, ensuring that Henry Hill, the film’s unreliable narrator and protagonist, felt like a truly lived-in character rather than a theatrical construct. This commitment to embodying the real individual amplified the film’s overall sense of raw, unfiltered reality.

Lorraine Bracco, as Karen Hill, approached her role with a deliberate choice not to meet the real Karen. She felt that “it would be better if the creation came from me,” opting for an internal understanding rather than direct mimicry. This choice allowed her to tap into a more universal truth about women entangled in the mob world, noting she saw no difference “between an abused wife and her character.” Her portrayal conveyed the emotional complexities and the difficult internal landscape of a woman seduced by the glamorous but brutal lifestyle, then trapped by its realities. The actors’ deep commitment to their roles, whether through extensive research or profound internal exploration, became a cornerstone of *Goodfellas*’ groundbreaking realism.

5. **The Power of Improvisation: Capturing Raw, Unscripted Reality**Perhaps nothing contributes more to *Goodfellas*’ feeling of raw, unscripted reality than Martin Scorsese’s innovative use of improvisation during the production. According to Joe Pesci, the director gave the actors significant freedom during rehearsals, allowing them to “do whatever they wanted.” Scorsese, ever the keen observer, would then make “transcripts of these sessions, took the lines that he liked most and put them into a revised script,” from which the cast worked during principal photography. This unique method blurred the lines between rehearsal and script, infusing the final product with an organic, spontaneous energy that is often difficult to achieve in tightly controlled productions.

This approach yielded some of the film’s most iconic and chilling moments, none more famous than the “Funny how? Do I amuse you?” scene involving Tommy and Henry. Pesci revealed that this terrifying exchange was based on an actual event he experienced as a waiter, where he innocently complimented a mobster by calling him “funny,” only for the comment to be misinterpreted with frightening intensity. This real-life anecdote, brought to rehearsals and improvised by Pesci and Liotta, was then refined by Scorsese into the chilling scene we see on screen.

The unscripted nature of these interactions created a palpable tension, a feeling that anything could happen at any moment, much like actual encounters within the criminal underworld. The dialogue doesn’t feel manufactured; it flows with a natural, unpredictable rhythm. The subtle shifts in tone, the sudden outbursts, and the uneasy silences are all remnants of those improvisational sessions, lending an unparalleled authenticity to the characters’ dynamics and the volatile environment they inhabit.

Another memorable instance of improvisation is the dinner scene with Tommy’s mother, portrayed by Scorsese’s own mother, Catherine. The only scripted line in this entire sequence was “Did Tommy tell you about my painting?” The rest of the conversation, the casual banter, the motherly concern, and the darkly humorous attempts to dispose of a corpse, emerged organically from the actors’ interactions. This scene perfectly encapsulates the film’s ability to blend the domestic with the macabre, the everyday with the extraordinary, highlighting the surreal normalcy of mob life where horrific acts are discussed over dinner. This commitment to spontaneous, character-driven dialogue is a testament to Scorsese’s genius and a cornerstone of *Goodfellas*’ enduring power to feel incredibly real. This organic approach to dialogue, born from the actors’ lived experiences and creative freedom, allowed *Goodfellas* to capture the genuine, often unsettling, rhythms of the mob world, making it feel less like a performance and more like a window into a hidden reality.

Having laid the groundwork for *Goodfellas*’ revolutionary approach to the gangster genre, we now pivot to the visceral elements that cemented its legacy. Martin Scorsese didn’t just tell a story; he crafted an experience, a relentless assault on the senses that mirrored the chaotic, seductive, and ultimately destructive world of Henry Hill. The cinematic techniques employed were not mere stylistic flourishes; they were integral to immersing the audience in the narrative, forcing a confrontational intimacy with the characters and their brutal reality.

Scorsese’s artistic choices were a deliberate rejection of convention, a visual language that spoke volumes about the characters’ lives. As he explained, he wanted “lots of movement and I wanted it to be throughout the whole picture,” ensuring the audience was constantly swept up in the narrative’s current. This frenetic pace, coupled with a deep attention to detail in every frame, was designed to convey the sheer richness and overwhelming nature of the gangster life. It’s a world where every moment is charged, every decision carries weight, and the calm before the storm is often indistinguishable from the storm itself.

6. **The Unflinching Camera: Visceral Techniques and Narrative Chaos**Martin Scorsese’s filmmaking in *Goodfellas* is a masterclass in controlled chaos, a calculated assault on traditional cinematic norms that serves to amplify the film’s gritty realism. He explicitly drew inspiration from the French New Wave, aiming to use “all the basic tricks of the New Wave from around 1961,” which included an abundance of narration, lightning-fast edits, sudden freeze frames, and rapid shifts between different locations. This ‘reckless attitude toward convention’ was more than just a stylistic choice; it was a deliberate mirroring of the characters’ own ‘punk attitude’ towards societal rules and expectations.

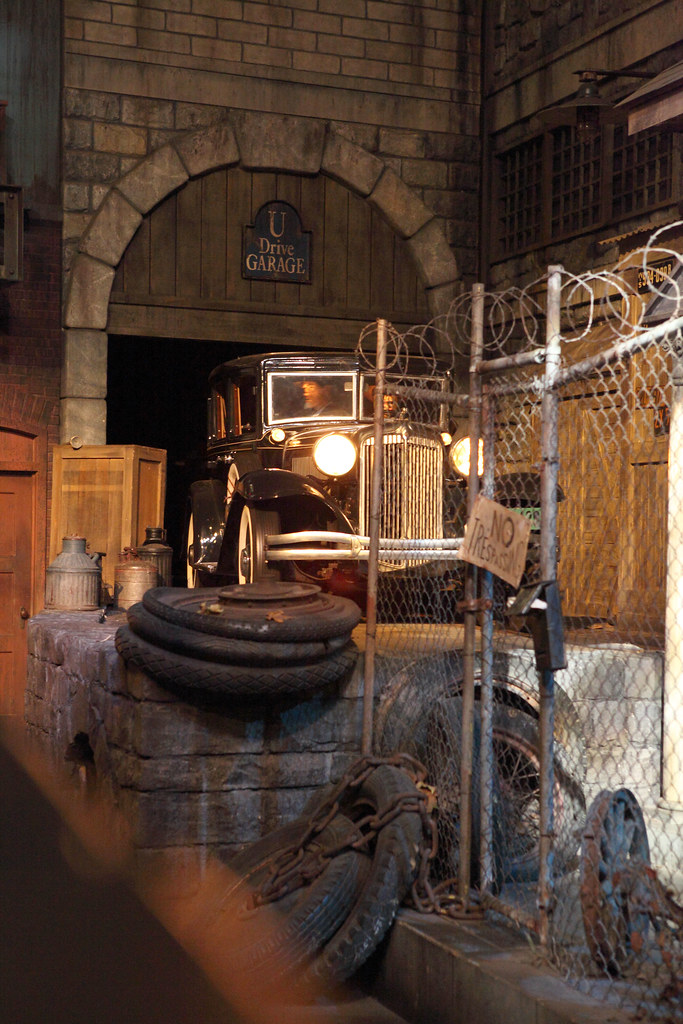

The director’s aim was to “almost overwhelm the audience with images and information,” plunging them headfirst into Henry Hill’s tumultuous existence. The infamous long tracking shot through the Copacabana nightclub perfectly encapsulates this philosophy. It wasn’t just a technical marvel born out of logistical necessity—the filmmakers couldn’t get permission for a direct route—but a symbolic journey. Scorsese revealed it was meant to symbolize that “Henry’s entire life was ahead of him,” simultaneously representing “his seduction of her [Karen] and it’s also the lifestyle seducing him.” It’s an unbroken take that pulls the audience into the intoxicating allure, making them complicit in the glamor, before the inevitable descent begins.

This visual and narrative strategy becomes increasingly pronounced as Henry’s world unravels. Scorsese intentionally designed the film’s style to “break down by the end, so that by [Henry’s] last day as a wise guy, it’s as if the whole picture would be out of control.” This cinematic fracturing mirrors Henry’s own escalating paranoia and drug-induced anxiety, forcing the viewer to experience his psychological disintegration through a barrage of disorienting cuts and frantic camerawork. Freeze frames, sparingly used, were specifically employed to highlight that “a point was being reached” in Henry’s life, serving as jarring punctuation marks that underscore critical turning points without needing explicit exposition.

The visual density, with “plenty of detail in every frame,” reflects Scorsese’s belief that the gangster life itself is incredibly rich and complex, overflowing with sensory information. This meticulous attention to the minutiae of their world, from the lavish parties to the stark interiors of their homes, grounds the narrative in a tangible reality. It creates an almost hyper-realistic environment where every object, every gesture, and every fleeting expression contributes to the film’s immersive quality, ensuring that the audience feels not just like observers, but like temporary inhabitants of this dangerous, captivating world.

7. **Violence Unvarnished: The Brutal Honesty of Mob Life***Goodfellas* stands apart for its depiction of violence, which is neither glorified nor sensationalized, but rather presented with a chilling, brutal honesty. Scorsese’s explicit intention was to portray violence realistically, describing it as “‘cold, unfeeling and horrible. Almost incidental’.” This unromanticized approach sharply contrasts with the more operatic and stylized violence often found in other gangster films, stripping away any sense of heroism or tragic grandeur. It’s not about epic confrontations but about sudden, messy, and often senseless acts that highlight the capricious nature of mob power.

The film wastes no time in establishing this tone, from the opening trunk scene where a still-living Billy Batts is brutally stabbed. Later, the unsanctioned murder of Batts by Tommy and Jimmy, in response to a trivial insult, is depicted with a visceral, almost sickening casualness. The subsequent desperate scramble to bury the body, followed by the grotesque necessity of exhuming and relocating the decaying corpse six months later due to impending development, strips away any romanticism from the act, revealing the crude, messy practicalities of mob violence. It’s a chilling reminder that these are men concerned with consequences, but not necessarily remorse.

Joe Pesci, in embodying the terrifyingly volatile Tommy DeVito, even found his character’s acts challenging to perform. He recounted how he struggled with the scene where Tommy kills Spider, eventually forcing himself to “feel the way Tommy did.” This commitment to internalizing the character’s casual brutality translates into a performance that is genuinely unsettling, making Tommy an emblem of the arbitrary and terrifying nature of violence within the mob. His outbursts aren’t carefully orchestrated; they are impulsive, explosive, and devastating, reflecting a world where life can be extinguished over the slightest perceived slight.

Even in the aftermath of calculated acts of violence, the film maintains its unflinching gaze. The Lufthansa heist, a meticulously planned operation, quickly devolves into a paranoid bloodbath as Jimmy, desperate to tie up loose ends and recover any expensive items purchased against his orders, systematically eliminates most of the crew. These aren’t dramatic shootouts; they are cold-blooded executions, swift and without fanfare, reinforcing the transactional and disposable nature of human life within this criminal ecosystem. This stark, matter-of-fact portrayal of violence ensures that its horror resonates deeply, revealing the true cost of the wiseguy life.

8. **The Price of Paradise: Henry Hill’s Descent into Paranoia and Regret**While *Goodfellas* seduces with its initial depiction of the glamorous mob life, it ruthlessly charts Henry Hill’s agonizing descent into paranoia and regret, illustrating the ultimate, crushing price of that intoxicating lifestyle. By 1980, the once-exhilarated Henry is reduced to a “nervous wreck due to heavy cocaine use,” a visual and psychological embodiment of the film’s stylistic breakdown. The rapid cuts and frantic camera movements, which once conveyed the thrill of his early days, now amplify his drug-fueled anxiety, making the audience share in his disoriented, frantic state.

His financial vulnerability, a stark counterpoint to the earlier displays of wealth, becomes painfully evident when Karen is forced to flush $60,000 worth of cocaine down the toilet during an FBI raid, leaving the Hills “penniless.” This sudden loss underscores the precariousness of their illicit gains, revealing that the lavish lifestyle was built on an unstable foundation. The transactional nature of their relationships is further exposed when Paulie, feeling betrayed by Henry’s continued drug dealing and viewing him as a liability, coldly hands him $3,200 and definitively ends their long-standing association. This moment marks a critical turning point, signifying Henry’s complete isolation from the only world he ever knew.

The culmination of Henry’s paranoia arrives with Jimmy’s suspicious request for him to travel to a hit assignment, which Henry correctly interprets as a death sentence. This realization prompts his desperate decision to become an informant, a final act of self-preservation that shatters any remaining illusions of loyalty or camaraderie. It’s a pragmatic choice born of fear, stripping away any romantic notions of honor among thieves. His testimony subsequently convicts Paulie and Jimmy, leading him and his family into the witness protection program, a fate he both seeks and despises.

The film concludes with Henry in a neighborhood in an undisclosed location, his former life exchanged for a mundane, anonymous existence. His famous lament—that he is condemned to live a “boring, average life as a ‘schnook'”—perfectly encapsulates his profound unhappiness and regret. Scorsese deliberately aimed to evoke anger from the audience towards Henry and “maybe with the system which allows this,” challenging viewers to confront the moral complexities of his choices and the true consequences of a life lived outside the law. It’s a powerful, lingering portrait of a man trapped by his past, yearning for a dangerous world that nearly destroyed him, unable to find contentment in the safety he bought with betrayal.

9. **A Soundtrack to Anarchy: Music as a Character in Goodfellas**One of *Goodfellas*’ most distinctive and influential elements is its innovative soundtrack, which, instead of incidental scoring, features a meticulously curated collection of popular music that acts almost as an additional character. Scorsese made a deliberate choice to use songs that “obliquely commented on the scene or the characters,” allowing the music to provide emotional depth, thematic context, and even ironic counterpoint to the unfolding narrative. This approach imbues the film with an immediate, visceral energy, pulling the audience further into the characters’ world.

A key rule for Scorsese was that he would “only use music contemporary to or older than the scene’s setting,” ensuring chronological authenticity. This commitment grounds the film in specific eras, with each song evoking the mood and cultural landscape of the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s as Henry’s life progresses. Remarkably, many of the non-dialogue scenes were shot “to playback,” meaning the actors performed to the pre-selected music, which profoundly influenced their performances and the scene’s rhythm. This method integrated the music deeply into the film’s fabric, making it an organic part of the storytelling rather than a mere accompaniment.

The power of the soundtrack is perhaps best exemplified during the chilling sequence where the dead bodies of the Lufthansa heist crew are discovered. Scorsese had “Layla” by Derek and the Dominos playing on the set during filming, and the song’s mournful, bluesy melody adds a profound, almost elegiac, dimension to the gruesome discoveries in the car, dumpster, and meat truck. The juxtaposition of the beautiful, poignant music with the horrific visuals creates a powerful emotional dissonance that reinforces the film’s theme of violence being “cold, unfeeling and horrible. Almost incidental.”

Beyond setting the mood, the lyrics of certain songs were sometimes “inserted between lines of dialogue to comment on the action,” creating a subtle layer of narrative insight. This intricate interplay between dialogue, visuals, and music ensures that the soundtrack is far more than background noise; it’s a dynamic storytelling device. Some of these musical choices were “written into the script” from the outset, while others were discovered by Scorsese during the intricate editing process, a testament to his keen ear and profound understanding of how music could elevate his narrative, making *Goodfellas* an auditory as much as a visual masterpiece.

10. **Beyond the Red Carpet: Goodfellas’ Enduring Legacy and Challenge to the Genre***Goodfellas* is not merely a film; it is a cinematic landmark, widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made and, critically, one of the most significant in the gangster genre. Its profound impact is evident in its preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress in 2000, deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” This recognition underscores its enduring relevance and its pivotal role in shaping both film history and popular culture, setting a new benchmark for authenticity and narrative daring.

The film’s critical reception was overwhelmingly positive, with legendary critics like Roger Ebert declaring, “No finer film has ever been made about organized crime – not even The Godfather.” This bold statement highlights *Goodfellas*’ implicit challenge to the genre’s traditional narratives, specifically its operatic and classical predecessors. Ebert later cemented its status by naming it the “best mob movie ever” and placing it among the ten best films of the 1990s, a sentiment echoed by numerous critics’ polls that consistently rank it among the greatest films of all time.

Perhaps the most telling testament to its legacy comes from within the industry, particularly from David Chase, the creator of *The Sopranos*. Chase openly acknowledged *Goodfellas* as “a very important movie to me,” praising its unique blend of humor and brutality that “felt very real.” He explicitly contrasted it with *The Godfather*, noting its “operatic, classical” feel compared to *Goodfellas*’ grounded realism. Chase admitted that *The Sopranos* “learned a lot from that,” demonstrating how Scorsese’s film paved the way for more nuanced and realistic portrayals of mob life in subsequent media, including the remarkable fact that the film shares a total of 27 actors with *The Sopranos*.

Its influence extends far beyond *The Sopranos*, with its “content and style” having been “emulated in numerous other pieces of media,” from documentaries like ESPN’s *Playing for the Mob* to feature films such as Luc Besson’s *The Family*, where Robert De Niro’s gangster character watches *Goodfellas*. Ranked as the #2 gangster film by the AFI’s 10 Top 10 list and consistently appearing on lists of the greatest films by Empire, Total Film, and Sight & Sound, *Goodfellas* stands as a titan. It is, as the critical consensus on Rotten Tomatoes states, “arguably the high point of Martin Scorsese’s career,” a film that didn’t just tell a story, but redefined an entire genre and forever changed how we perceive the gritty, unglamorous reality of the criminal underworld.

Through its relentless pace, raw honesty, and unvarnished depiction of a life consumed by its own seductive brutality, *Goodfellas* doesn’t just entertain; it confronts. It’s a cinematic experience that continues to resonate, not just for its groundbreaking techniques or its unforgettable performances, but for its courage to pull back the curtain on a world often romanticized, revealing the stark, often uncomfortable truth that lies beneath the surface. Decades on, its power remains undiminished, forcing us to re-evaluate what we think we know about organized crime and, indeed, about the very nature of storytelling itself. This isn’t just a movie about gangsters; it’s a profound, unflinching look into the human condition, stripped bare of illusion.