The journey of entrepreneurship, as J. K. Rowling famously stated in her 2008 Harvard Commencement Address, is one where “It is impossible to live without failing at something, unless you live so cautiously that you might as well not have lived at all—in which case, you fail by default.” This profound truth resonates deeply within the annals of business history, where even the most visionary leaders encounter monumental missteps.

Indeed, many well-known businesspeople, from candy maker Milton Hershey to cartoonist Walt Disney, have faced setbacks before achieving greatness, or after. The crucial distinction lies not in avoiding failure, but in embracing it as a teacher, a “temporary detour, not a dead end,” as motivational speaker Dennis Waitley wisely put it. It is about learning, adapting, and persevering in an ever-changing world where risk is an unavoidable constant.

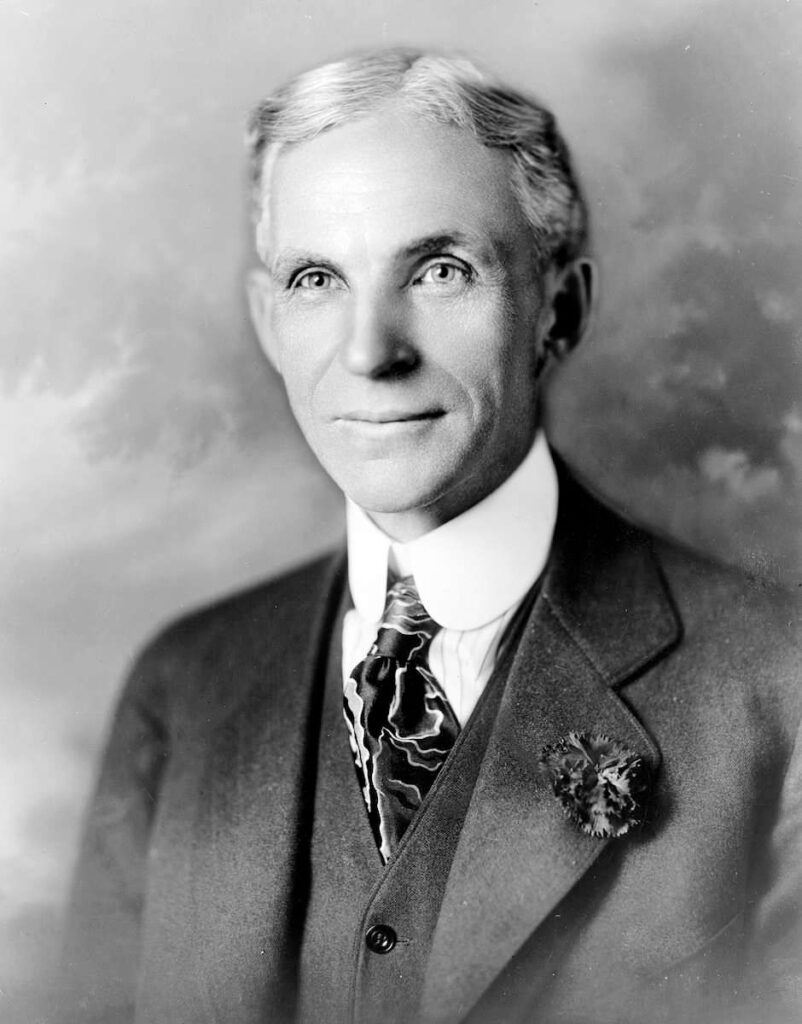

Henry Ford, a name synonymous with industrial revolution and mass production, stands as a titan among these daring individuals. He was a man who, in the words of Theodore Roosevelt’s “Man in the Arena” speech, truly “strives valiantly” and “spends himself in a worthy cause.” Yet, even Ford, whose ingenuity enriched countless lives and amassed immense personal wealth, made business decisions that, in retrospect, serve as powerful cautionary tales for any modern enterprise. These decisions, though perhaps rooted in grand vision, nearly ruined the very company he built.

1. **Prioritizing Social Welfare Over Shareholder Returns: The Dividend Cut Justification**One of Henry Ford’s most enduring and legally significant blunders emerged from the infamous Dodge v. Ford case in 1916. In a move that shocked minority stockholders, particularly the Dodge brothers, Ford Motor Company drastically slashed its dividend. This wasn’t merely a cost-cutting measure; Ford publicly articulated a rationale that directly challenged the prevailing corporate ethos of the time.

He justified skipping the dividend by asserting a broader corporate purpose: “he sought to do well for employees and America’s car buyers, with corporate profits a secondary motivation.” This philosophy, prioritizing the welfare of his workforce and the affordability of his cars over the immediate financial gratification of shareholders, was radical. While today we might recognize elements of stakeholder capitalism in this approach, in 1916, it was a direct affront to established legal principles.

The court, however, largely rejected Ford’s justifications for holding back the dividend. Its decision established a foundational principle in corporate law: that a corporation’s primary purpose is to generate profit for its shareholders. The legal system, at that time, did not recognize Ford’s vision of a company as a social utility, leading to a successful lawsuit by the Dodge brothers and a court-ordered “big dividend payout.”

While some interpretations suggest Ford’s motivation was to “squeeze out the Dodge brothers” to prevent them from funding their own car company, several transactional aspects undercut this as the sole reason. The Dodge brothers had previously offered to sell their stock for a price close to what Ford eventually paid. Moreover, Ford Motor’s underlying expenses that necessitated the dividend cut were many multiples of any savings from the Dodge brothers’ original sellout offer, suggesting a broader financial pressure. Regardless of the underlying motive, the public justification and the subsequent legal defeat made this a pivotal and costly misjudgment, setting a precedent that still resonates in corporate governance discussions today.

2. **The Massive Vertical Integration of River Rouge**Following the undeniable success of Ford’s assembly line in 1913, which yielded Ford Motor a “very valuable monopoly” and “tremendous” profits, Henry Ford conceived an even grander vision: the River Rouge complex. This was not just another factory; it was an industrial marvel designed to be “the largest factory on the planet” when completed, embodying an unprecedented level of vertical integration.

Ford planned for the River Rouge complex to begin the manufacturing process by “smelting the steel that would turn into Model T cars rolling off the assembly line at the end of the River Rouge factory.” This decision to control every aspect of production, from raw materials to finished product, was driven by a desire to maintain his immense market share and perpetuate his monopoly. He aimed for self-sufficiency and unparalleled efficiency, believing this would solidify Ford Motor’s dominance in the burgeoning automotive industry.

However, this audacious undertaking demanded “much cash on labor and on expanding physical capacity.” The sheer scale of the investment meant that significant corporate profits, which previously flowed freely, now had to be redirected. In an era of “more primitive financing choices,” this massive allocation of capital meant “less, or none, was available for dividends.” This direct financial consequence was a major factor contributing to the dividend cut that ultimately led to the Dodge v. Ford litigation.

The River Rouge complex, while a testament to Ford’s ambition, represented a colossal bet on a single, highly integrated industrial model. Such a massive, fixed investment carried inherent risks: it reduced financial flexibility, made the company less adaptable to future technological changes or market shifts, and tied immense capital to an incredibly specific production paradigm. The decision, though strategic in intent, created immense financial strain and contributed directly to the company’s legal battles and shareholder discontent.

Read more about: Ford’s Transformative Leap: Unpacking the Historic Headquarters Relocation and Vision for Future Innovation

3. **The $5/Day Wage Policy**In January 1914, Ford Motor Company made headlines with an announcement that sent shockwaves through the industrial world: it doubled assembly-line workers’ wage rate to the famous $5/day. This was an extraordinary sum for the time, far exceeding typical industrial wages. While often hailed as a progressive labor policy, from a purely business decision standpoint, it was a massive, voluntary expenditure that profoundly impacted the company’s financial structure and contributed to its shareholder disputes.

This decision was not born purely out of philanthropy but out of pressing business necessity. The assembly line, though revolutionary, was characterized by “tedium.” Workers, facing repetitive and demanding tasks, were restless. A “radical union—the Wobblies—sought to organize the Ford Motor workers,” a threat taken seriously by Detroit’s industrialists. Ford faced a dire labor problem and understood he “could not maintain his monopoly without sufficient worker buy-in.”

The $5/day wage was Ford’s audacious strategy to turn back union organizers and keep his workforce motivated and acquiescent to the demands of the assembly line and the planned River Rouge complex. It was an investment in labor stability and productivity, a calculated move to secure his monopoly. The context clearly states that “for River Rouge to succeed, further worker buy-in to the ambitious factory was necessary.”

Yet, this “labor-friendly strategy” came at a significant cost. Combined with the River Rouge expansion, it “cost much cash.” Redirecting this substantial cash flow from Ford Motor’s operations “to construction and to labor buy-in meant that (in those days of more primitive financing choices) less, or none, was available for dividends.” This decision, while arguably effective in managing labor and preserving the monopoly, directly exacerbated the financial pressures that triggered the Dodges’ lawsuit, creating an uneasy “labor-owner coalition that was splitting a monopoly profit” and causing immense shareholder friction.

4. **The Fordlandia Venture – A Utopian Dream Drowned in the Amazon**Henry Ford, a visionary defined by his relentless pursuit of solving industrial challenges, faced a significant bottleneck in his automotive empire: a burgeoning British rubber monopoly. This dependence on external suppliers for a critical component—rubber for his Model T tires—was a problem he simply could not abide. His ambitious counter-strategy, devised in the mid-1920s, involved establishing an independent, self-sufficient rubber supply by venturing directly into the heart of Brazil’s Amazon region.

In 1927, Ford solidified a colossal agreement with the Brazilian government, securing an astounding 2.5 million acres along the Tapajos River. This vast tract was earmarked for more than mere rubber cultivation; it was to be the site of a pioneering social and industrial experiment. Ford envisioned a sprawling, American-style utopian town, which he famously christened “Fordlandia,” where his Midwestern values and industrial efficiency would take root, simultaneously guaranteeing a consistent rubber supply for his global manufacturing operations.

However, this “gargantuan gamble,” as it later became known, rapidly proved to be a “Herculean challenge” fraught with unforeseen and ultimately insurmountable difficulties. Logistically, managing a massive industrial complex and a town located 4,000 miles from Ford’s Michigan headquarters presented unprecedented hurdles in terms of transporting supplies, overseeing personnel, and maintaining effective communication. Environmentally, Ford’s management applied conventional industrial farming techniques to a delicate tropical ecosystem, making a critical error. They densely planted a monoculture of rubber trees, rendering them highly susceptible to local pests and diseases that quickly decimated the plantations, a fundamental misjudgment of the biome.

Culturally, the endeavor was an unmitigated disaster that starkly exposed Ford’s lack of cultural sensitivity. Brazilian workers, unaccustomed to and deeply resistant to the rigid American lifestyle imposed upon them, profoundly resented the unfamiliar American cuisine and, perhaps even more, Ford’s strict prohibition on alcohol, which extended even to their private residences. This fundamental clash of cultural values, combined with the catastrophic environmental setbacks and logistical nightmares, led to widespread discontent, frequent riots, and ultimately, the project’s rapid collapse. “It took only six years before Fordlandia collapsed,” forcing Ford to abandon the initial site and later relocate operations further upriver, though these secondary efforts also proved unsustainable and were shut down within a decade.

The final blow to Ford’s Amazonian dream came with the technological advancements of the 1940s. The invention and widespread adoption of synthetic rubber effectively rendered natural rubber plantations, particularly costly and problem-ridden ones like Fordlandia, largely obsolete. Ford’s grandson, Henry II, eventually conceded defeat and sold the entire, sprawling enterprise back to the Brazilian government in 1945. The financial toll was staggering, representing a loss of nearly $300 million in today’s dollars, serving as a powerful, cautionary tale that even the most ambitious visions require flexibility, cultural sensitivity, and a profound understanding of local conditions to succeed.

5. **The Model T Fixation – Refusing to Adapt to a Changing Market**The launch of the Ford Model T in 1908 marked a pivotal moment in industrial and social history. It was lauded as a cutting-edge automobile, presenting an unparalleled blend of “innovation and reliability” at an accessible price point. By democratizing car ownership, the Model T fundamentally transformed American life and cemented Ford Motor Company’s position as the undisputed leader in the rapidly expanding automotive sector. This immense success brought Henry Ford “untold riches and power and pleasure,” solidifying his legendary status as an industrial pioneer.

However, this very triumph inadvertently cultivated an unhealthy degree of attachment and strategic inflexibility in Ford himself. As early as 1912, a mere four years after the Model T’s groundbreaking debut, perceptive voices within the company began to advocate for significant updates and modernization. Ford’s chief aides, driven by a desire to innovate and secure the company’s future, went so far as to secretly develop a prototype of a new, low-slung Model T, which they proudly displayed, gleaming with polished red lacquer, on the factory floor.

Ford’s response to this forward-thinking initiative was both legendary and alarmingly violent, becoming a stark illustration of his stubborn resistance to change. An eyewitness vividly recounted Ford circling the innovative prototype, his hands initially deep in his pockets, before abruptly seizing the car door and, with a powerful “bang! He ripped the door right off!” He then proceeded, in a shocking and furious display of possessive anger, to “destroy the whole car with his bare hands.” This visceral act delivered an unmistakable and chilling message to his entire engineering and design team: they were “not to mess with his prize creation.” For Henry Ford, the Model T transcended being merely a product; it had become an immutable symbol of his genius, a perfect design that, in his unyielding view, simply required no further alteration.

This deeply ingrained “fixation with his masterpiece,” as eloquently described by Robert Lacey, condemned the Ford Motor Company to a prolonged period of technological stagnation. For over 15 critical years, by 1925, the Model T remained fundamentally unchanged from its original specifications. It stubbornly retained its “noisy, underpowered four-cylinder engine, obsolete ‘planetary’ transmission, and horse-buggy suspension,” features increasingly outmoded in a rapidly advancing industry. While Ford eventually permitted minor concessions, such as balloon tires, an electric starter, and a floor-mounted gas pedal, and expanded the color options beyond the original black, the core vehicle remained, in essence, a relic of a bygone era. A candid New York Ford dealer astutely captured this sentiment, lamenting that “You can paint up a barn, but it will still be a barn and not a parlor.”

The market, critically, was not static; it was a vibrant, evolving entity that continued to advance at a furious pace. While Ford, as Lacey noted, “rested on his laurels,” his competitors were relentlessly innovating, meticulously attuned to the changing preferences and escalating demands of American drivers. The direct and devastating consequence of Ford’s strategic rigidity was a precipitous decline in his company’s once-unassailable market share. It plummeted from a commanding 57% of U.S. automobile sales in 1923 to just 45% in 1925, and further down to a sobering 34% in 1926. This dramatic erosion of market leadership served as a painful, irrefutable lesson in the severe peril of complacency and the absolute criticality of continuous adaptation within a relentlessly dynamic industrial landscape.

6. **Underestimating Competition and Ignoring Market Evolution**Henry Ford’s unyielding attachment to the Model T and his stubborn refusal to meaningfully evolve its design created an immense strategic vulnerability within the booming automotive market. This critical vacuum was swiftly and aggressively exploited by his competitors, who demonstrated a keen understanding of consumer desires and a proactive embrace of technological advancements. This period marked one of Ford’s most profound strategic missteps: a categorical failure to acknowledge competitive innovation and the relentless pace of market evolution. While Ford remained steadfastly fixated on his original “Tin Lizzie,” a vehicle optimized for the rugged dirt roads of an earlier era, rival companies like Dodge and General Motors were actively charting a bold new course for the industry.

These forward-thinking competitors were not merely making cosmetic adjustments; they were pioneering significant mechanical and design improvements that fundamentally redefined the driving experience and consumer expectations. They introduced more powerful and inherently smoother six-cylinder engines, offering a vastly superior performance profile compared to Ford’s increasingly antiquated four-cylinder. Furthermore, the Model T’s unique, often cumbersome “planetary” transmission was gradually supplanted by more conventional, efficient, and user-friendly manual clutch-and-gearshift transmissions, making driving more intuitive and enjoyable for a wider demographic.

Crucially, these new generations of vehicles were meticulously designed with the nation’s rapidly expanding infrastructure in mind. The advanced models possessed the power and engineering to travel comfortably and safely at higher speeds, a necessity given the burgeoning network of paved highways that were transforming American travel. Ford’s archaic design, specifically optimized for rugged dirt tracks, simply could not compete effectively on these modern thoroughfares, creating a glaring disparity in driving experience and utility.

Automobile buyers, now increasingly affluent and discerning, were keenly aware of these advancements. They began actively “trading up” to these modern, comfortable, and powerful vehicles that were far better suited to the evolving transportation landscape and their aspirational lifestyles. Ford’s once-unassailable market leadership consequently evaporated as consumers increasingly opted for vehicles that embodied contemporary innovation and convenience, rather than clinging to historical reliability alone.

The impact on Ford Motor Company’s market position was truly calamitous and difficult to reverse. Its once-dominant lead steadily eroded as consumers migrated to more forward-thinking brands. By May 1927, when Ford finally acknowledged the inevitable and announced the development of a replacement for the Model T—the Model A—it was a reaction rather than a proactive step, and crucially, it was already too late to stem the tide. In that very year, Chevrolet, Ford’s burgeoning primary competitor, surpassed Ford in annual car sales for the first time in history, signaling a monumental and permanent shift in the automotive hierarchy.

Although the Model A enjoyed a brief resurgence upon its release, temporarily reclaiming first place for Ford in 1929, this triumph proved fleeting. Chevrolet swiftly regained its lead the following year and, as the historian Robert Lacey unequivocally notes, “never looked back.” The “once-proud Ford Motor Company had to be content with second place” from 1930 onwards, a position it would largely maintain for decades. This enduring shift serves as a potent and invaluable lesson for all businesses: complacency, particularly in the face of aggressive and agile competition, is a direct and often irreversible path to surrendering market leadership and, potentially, to corporate ruin.

**Conclusion: The Enduring Lessons from Ford’s Follies**

The comprehensive journey through Henry Ford’s most profound and strategically challenging business decisions offers a powerful, indeed enduring, truth for all enterprises: even the most brilliant, pioneering minds are not immune to monumental missteps. From his ambitious, yet ultimately ill-fated, utopian dream in Fordlandia to his stubborn, almost unwavering, adherence to the Model T’s increasingly antiquated design, Ford’s failures provide an invaluable trove of hard-won lessons for contemporary businesses of all sizes and across all sectors. These cautionary tales collectively underscore the critical importance of strategic agility and deep adaptability, highlight the insidious danger of complacency even when at the perceived pinnacle of market success, and emphasize the absolute necessity of continuously acknowledging and dynamically responding to evolving market dynamics and aggressive competitive innovation. In today’s relentlessly dynamic and interconnected commercial landscape, the capacity to genuinely learn from past mistakes—both your own organizational errors and the historical misjudgments of titans like Ford—is not merely a beneficial trait; it is, without doubt, an absolutely foundational prerequisite for achieving sustained success and maintaining long-term relevance. As Ford himself, with a notable touch of retrospective wisdom, once aptly observed, “Failure is simply the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently.” It stands as a compelling call to action for all entrepreneurs and business leaders: to dare greatly with vision, to strive valiantly with conviction, and, most crucially, to cultivate an unyielding commitment to continuous learning, iterative adaptation, and forward-thinking innovation in every facet of their enterprise.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/WalmartCheckOutLanesjpg-185b345695ce428284b7c66b5313b2d1.jpg)