In an industry where billions of dollars are exchanged, where box office records are celebrated, and where the most anticipated films can rake in fortunes worldwide, the concept of a wildly successful movie ultimately reporting no profit might sound like something out of a fantastical script itself. Yet, this is the peculiar reality of what has come to be known as ‘Hollywood accounting,’ a system so specific to the entertainment business that it boasts its own Wikipedia page, often leaving onlookers scratching their heads.

This unique approach to financial record-keeping frequently leads to scenarios where cinematic triumphs, films that have captured the hearts and wallets of audiences globally, officially exist ‘in the red.’ Such outcomes aren’t accidental oversights or mistakes; rather, they are the result of deeply entrenched, albeit complex and often contentious, accounting standards that diverge significantly from the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) followed by most other U.S. companies. It’s a system designed to maximize studio revenue while minimizing — or, indeed, eliminating — the very ‘profits’ many creatives are contractually promised.

To truly understand the intricacies of this system, which currently stands at the heart of major industry disputes and strikes, we must peel back the layers of revenue, expenses, and contractual obligations. This article will serve as your guide through the fascinating, perplexing, and undeniably powerful world of Hollywood accounting, dissecting the strategies that allow studios to operate with an unparalleled level of financial maneuvering. We’ll examine the core mechanisms, explore landmark cases, and shine a light on why even the most colossal blockbusters might, on paper, never make a cent of profit.

1. **Defining “Hollywood Accounting”: Beyond the GAAP**Hollywood accounting is a term that refers to the unique and often convoluted financial practices employed by studios and production companies within the entertainment industry. Unlike the standard bookkeeping that most U.S. companies adhere to under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), Hollywood’s system frequently diverges, creating a landscape where financial outcomes can appear counterintuitive, particularly concerning a film’s reported profitability.

Experts describe Hollywood accounting as a “wayward cousin” to traditional accounting, primarily because its tactics, while perfectly legal, involve what some might call “fantastical fictions.” The core objective behind these methods is often to manipulate reported profits, especially when contractual agreements tie talent compensation to these figures. This divergence from standard practices is not merely a technicality; it has profound implications for how revenue is distributed and who ultimately benefits from a film’s commercial success.

The system has been the source of countless court disputes over the years, yet it remains firmly established. It’s a testament to the industry’s power structures and the specialized nature of its financial dealings. Understanding Hollywood accounting requires an acceptance that the numbers publicly thrown around—like box office grosses and budgets—are often not truly indicative of a film’s financial success in the traditional sense, especially concerning profit participation for those involved in its creation.

2. **The Subsidiary System: Creating Unprofitable Entities on Paper**At the heart of many Hollywood accounting strategies is the ingenious use of subsidiaries. When a studio decides to make a movie, it commonly sets up a separate legal entity, a subsidiary, specifically for that production. This structure is crucial because it allows the studio to enter into agreements where actors, writers, and other creatives are paid based on the *subsidiary’s* profits, rather than the studio’s overall earnings.

Once the subsidiary is established and begins the process of filmmaking, it inevitably incurs numerous expenses: crew wages, craft services, set design, props, and more. When the film is released and starts generating revenue from ticket sales, this income flows into the subsidiary. This is where the peculiar twist of Hollywood accounting becomes evident. The studio, which entirely owns and controls this little company, then charges the subsidiary substantial fees for distribution, advertising, and various other operational costs.

The subsidiary, by design, “agrees” to these new fees. These charges are often so inflated that they effectively consume all of the revenue generated by the film. Consequently, on paper, the subsidiary never shows a profit. The profits, in essence, go directly back to the studio in the form of these fee payments, creating a perfectly legal mechanism for the studio to maintain ownership of the film’s financial gains while technically reporting zero profit for the project itself.

3. **The Gross vs. Net Points Divide: Why “Take the Gross” is Key**For many involved in a film’s production, their compensation in a financial sense is tied to what are often referred to as “net points.” In theory, these net points would entitle actors, directors, writers, or producers to a percentage of whatever profits remain after the studio has recouped all its expenses. However, as the mechanics of Hollywood accounting demonstrate, a film’s net profit can, by design, be perpetually zero, rendering net points largely meaningless.

This explains why any experienced entertainment lawyer advises their client to “take the gross.” Acquiring “gross points” is a crucial alternative to net profit participation, particularly for high-profile talent with significant leverage. A deal based on gross points directly diverts a portion of the box office revenue to the participant *before* other costs are recouped, regardless of whether the film technically registers a net profit for the subsidiary.

Such “gross points” deals are, understandably, rare and typically reserved for AAA-list talent like Sandra Bullock, who famously negotiated a substantial upfront payment for Alfonso Cuaron’s ‘Gravity’ plus 15% of the blockbuster’s first-dollar gross. This allowed her to pocket at least $70 million, illustrating a powerful counter-strategy against the studio’s profit-minimizing tactics. For most creatives without this extreme degree of leverage, net points often mean receiving nothing, highlighting the vast disparity in compensation structures within the industry.

4. **Inflated Overheads and Arbitrary Fees: Siphoning Profits Legally**Beyond the basic subsidiary structure, a significant aspect of Hollywood accounting involves the strategic inflation of overhead allocations and the application of arbitrary fees. Bridget Stomberg, an accounting professor, notes that “some people suspect the overhead allocations to any one movie can be arbitrary and excessive with the goal of making movies look unprofitable.” These overheads represent the studio’s general operating expenses, which are then charged back to individual film projects.

These charges add up quickly and encompass a wide range of costs, from distributing films widely to theaters, paid TV channels, streaming services, and airlines, to massive marketing costs and interest payments on debt, as S. Mark Young, an accounting professor, explains. The effect is often to “swamp the revenues from the film, resulting in zero profits or losses” on paper. The studio’s actions are within their purview, legally speaking, but they are certainly motivated to reduce profits as much as possible.

Critically, these expense allocations are often internal transactions between the parent studio and its wholly-owned subsidiary. While they allow the studio to minimize a film’s reported profit for talent payout purposes, they generally do not affect the net profits that the studio’s shareholders ultimately see, as these transactions are typically eliminated when companies consolidate their earnings. This reinforces the idea that the primary motivation for these inflated costs is to avoid paying out profit-sharing obligations to creatives, rather than generating tax savings or other financial benefits for the larger corporation.

5. **The Art Buchwald Landmark Case: When Hollywood Numbers First Lied in Court**The deceptive nature of Hollywood accounting was brought dramatically to light in a landmark legal battle involving humorist and Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Art Buchwald. In the early 1980s, Buchwald developed a movie treatment, ‘It’s a Crude, Crude World,’ about an African prince traveling to the U.S. This idea eventually made its way to Paramount, where it was developed into a screenplay titled ‘King for a Day.’

When Paramount later released ‘Coming to America’ in 1988, starring Eddie Murphy, Buchwald noticed striking similarities to his original concept but found his name conspicuously absent from the credits. He sued, claiming plagiarism, and ultimately won. However, the true significance of his case emerged when a judge ruled that he was owed a share of the net profits, transforming a minor spat into “an historic legal battle over the way the motion picture studios keep their books and diddle their talent,” as described by his attorney, Pierce O’Donnell.

Paramount argued that despite earning $289 million worldwide, ‘Coming to America’ was still in the red, claiming exorbitant marketing and distribution costs had eliminated any net profit. The judge famously deemed this defense “unconscionable,” exposing the studio’s creative accounting practices. Buchwald and his co-plaintiff were awarded $900,000 in a 1992 settlement, providing the world with concrete judicial proof that Hollywood numbers could indeed be manipulated to obscure true profitability, marking a pivotal moment in the ongoing scrutiny of industry accounting.

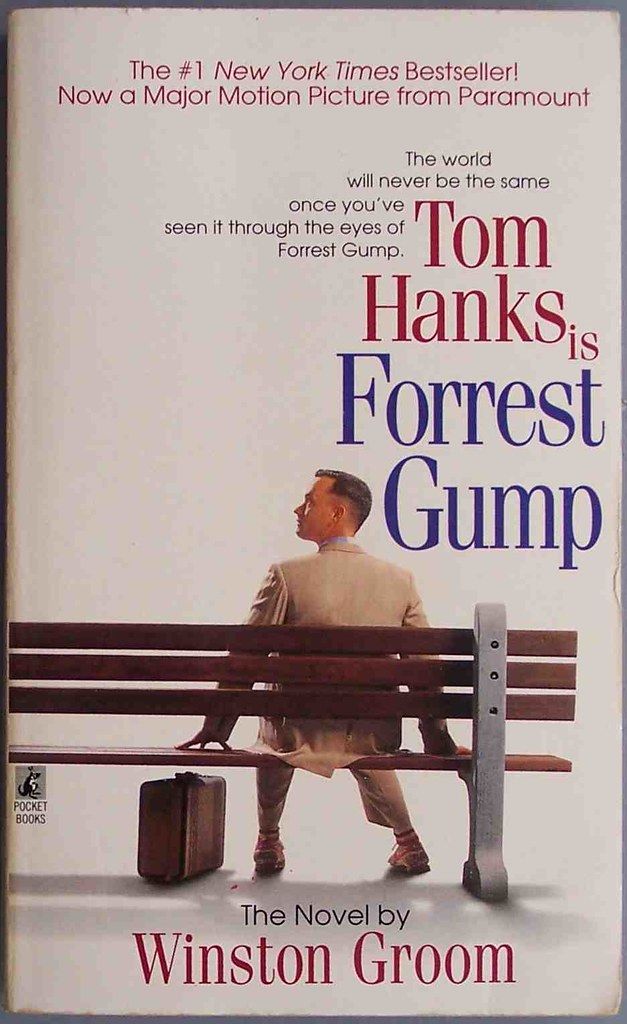

6. **”Forrest Gump” and “Return of the Jedi”: Blockbusters with Zero Profit**Two of the most frequently cited and startling examples of Hollywood accounting in action are the blockbuster films ‘Forrest Gump’ and ‘Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi.’ Both films were monumental successes, grossing hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office and achieving iconic status, yet both officially reported never having made a single penny of profit for their respective studios. This outcome is a stark illustration of how the system functions.

‘Forrest Gump,’ despite selling over $300 million worth of tickets (and later noted as $667 million earnings versus $31 million ‘loss’), was declared by the studio that made it to have generated no profit. Similarly, ‘Return of the Jedi’ earned over $475 million against a $32 million budget, cementing its status as one of the biggest blockbusters of all time, yet Lucasfilm claimed the film never made a cent of profit. These instances defy conventional business logic, where such massive revenue typically translates to significant profitability.

The primary incentive for studios to engage in this kind of accounting is to minimize their liabilities for profit-sharing deals included in the contracts of actors and other creatives. If a film technically shows no profit, the studio is not obligated to pay out these profit shares, regardless of the film’s immense commercial success. As the context explains, “No matter how successful the movie is, net profit may, by design, never exist.” These examples underscore the effectiveness of Hollywood accounting in insulating studios from profit-participation obligations, despite widespread public perception of a film’s financial triumph.

7. **”The Real Money Heist”: Beyond Simple Subsidiaries**While the basic subsidiary model forms the cornerstone of Hollywood accounting, the sophistication of these financial maneuvers extends far beyond merely setting up a shell company. Studios routinely employ more intricate strategies, such as utilizing additional shell companies specifically for advertising, marketing, and distribution. These entities serve as conduits, siphoning a film’s profits and funneling them directly back into the studio’s own coffers through a web of internal transactions.

Furthermore, studios can engage in what is described as a ‘reverse Tobashi scheme.’ This involves shifting costs within their internal operations and strategically cross-collateralizing the accounting of multiple projects. The ingenious application of this tactic means that a single box office flop can, on paper, be transformed into two unprofitable films through creative and complex financial maneuvers, further obscuring true profitability.

Another advanced tactic involves studios establishing reserves for future expenses or potential losses. They accomplish this by making deductions for contingencies, interest, and various additional costs, all of which are applied to artificially lower a film’s reported profits. These deductions, while seemingly prudent on the surface, serve to ensure that the declared net profit remains negligible, effectively sidestepping profit-sharing obligations.

The strategic deferral of revenue recognition is yet another sophisticated mechanism. By delaying when income is officially recorded, studios can further manipulate the balance sheet, ensuring that net points remain a largely meaningless metric for compensation. Such complex financial instruments are often presented with elaborate amortization schedules, expertly crafted to demonstrate why a creative’s anticipated cut of the profits amounts to precisely nothing, regardless of a film’s commercial success.

8. **The Illusion of Film Budgets: What Numbers Don’t Tell You**When we see a film’s official budget reported in industry publications like Variety or The Hollywood Reporter, it’s natural to assume this figure represents the true cost of production. However, this widely circulated number is often a carefully curated illusion. It fundamentally fails to account for a significant stream of income that studios receive from various external sources, fundamentally altering the real financial picture of a production.

Crucially, these published budgets almost never include the substantial funds studios acquire through government subsidies, lucrative tax shelter deals, or embedded product placement arrangements. These are all legitimate ways a studio secures funding that directly offsets the amount it genuinely spends out of its own pocket. The omission of these financial inputs means that the reported budget is far from a comprehensive reflection of the film’s actual economic outlay.

This deliberate lack of transparency allows Hollywood studios to engage in a form of ‘double accounting,’ where the true cost of production is known only within their inner circles. Outsiders, including the public and often even those directly involved in the film’s creation, rarely gain insight into how much a movie genuinely costs to produce after all these various funding mechanisms are factored in.

Beyond the initial ‘negative cost’—the expenses incurred before prints and advertising—studios also maintain a tight silence regarding their marketing outlays. Furthermore, they are exceptionally secretive about non-theatrical revenues, which often eclipse box office earnings. This includes income from home entertainment, network and cable TV licensing, and a host of other ancillary sources. Without access to these comprehensive figures, it becomes virtually impossible for anyone outside the studio to accurately assess a film’s true profitability or even if it’s ‘in the black.’

9. **More Infamous Unprofitable Blockbusters: “Men In Black” and “Fahrenheit 9/11″**Even after the revelations of the Art Buchwald case and the mythical unprofitability of ‘Forrest Gump’ and ‘Return of the Jedi,’ Hollywood accounting continued to generate fresh, startling examples. The 1997 sci-fi blockbuster ‘Men In Black,’ starring Tommy Lee Jones and Will Smith, stands as a prominent illustration. Despite grossing nearly $600 million globally on a modest budget of $90 million and spawning three successful sequels, Sony Pictures officially claimed the film never broke even.

The absurdity of this claim was vocally highlighted by the movie’s screenwriter, Ed Solomon. In deeply sarcastic tweets, Solomon laid bare the creative accounting at play, stating, “My recent Men in Black profit statement proves that the film, though having generated over $595 million in revenue, has actually *cost* Sony over $598 million.” He quipped that the profit statement was “better science fiction than the film itself,” implying that Sony was intentionally keeping the film in the red to avoid significant talent payouts.

Similarly, Michael Moore’s documentary ‘Fahrenheit 9/11,’ a film that garnered international success with $220 million in earnings, astonishingly reported no profit. This outcome led to a lawsuit over Moore’s compensation, bringing to light the questionable practices surrounding expenses. A subsequent audit reportedly suggested that substantial amounts deducted for “advertising costs” were, in reality, being used for a private plane to fly a producer to Europe, painting a rather unflattering picture of the studio’s financial justifications.

These instances reinforce the pattern where massive commercial success is disconnected from reported profitability for contractual purposes. The detailed public outcry from figures like Ed Solomon and the findings from audits in cases such as Michael Moore’s underscore how these seemingly legal, yet deeply questionable, financial gymnastics are deployed to minimize studio liabilities for profit-sharing agreements, frustrating creatives who believe they are owed their fair share.

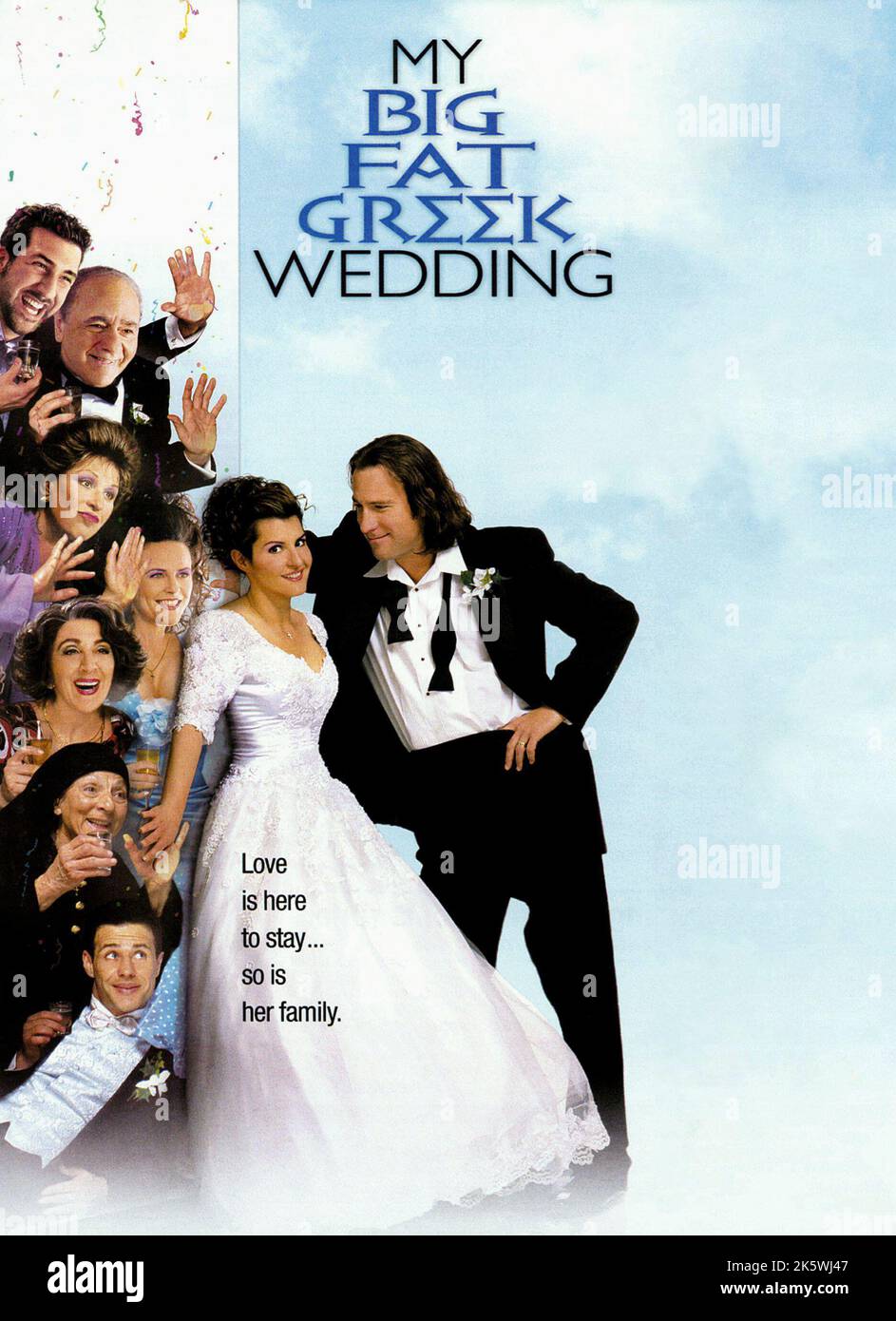

10. **”My Big Fat Greek Wedding” and “Lord of the Rings”: More Unbelievable Losses**The list of immensely successful films declared unprofitable under Hollywood accounting practices reads like a fantastical ledger. Another striking example is Peter Jackson’s monumental ‘The Lord of the Rings’ trilogy, which, despite its staggering box office runs yielding over $2.9 billion globally, officially “lost” a substantial amount of money. This claim becomes particularly baffling when one considers the studio’s subsequent decision to greenlight six additional films and an extremely expensive spin-off television series, with more reportedly in development.

Perhaps even more perplexing is the case of ‘My Big Fat Greek Wedding.’ This sleeper hit, which cost a mere $6 million to produce, went on to net over $350 million at the box office. Yet, incredibly, it was reported to have lost $20 million. Such figures defy all conventional business logic, highlighting the extraordinary lengths to which Hollywood accounting can go to manipulate financial outcomes on paper, particularly when profit participation is at stake.

These seemingly impossible outcomes extend to other major productions as well. Tim Burton’s ‘Batman,’ which earned $411 million, showed a $36 million deficit. ‘Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix,’ with earnings of $939 million, officially recorded a $167 million “loss.” Even films like ‘JFK’ ($150 million earnings) and ‘Coming to America’ ($288 million earnings) famously reported zero profit. In each of these cases, the vast disparity between box office success and declared profitability has fueled ongoing debates and legal challenges within the industry.

Behind every one of these notable cases of “unprofitable” blockbusters is an individual or group who, despite their film’s widespread success, was effectively denied their share of the net profits. These glaring examples serve as constant reminders of the inherent challenges faced by talent navigating contracts tied to elusive net points, further solidifying the need for astute negotiation and a deep understanding of the industry’s unique financial landscape.

11. **The Legality vs. Ethics Debate: A Contractual Reality**The most frequent question surrounding Hollywood accounting inevitably revolves around its legality and ethics. Experts generally agree that these creative accounting tactics, while often involving “fantastical fictions” and appearing deeply counterintuitive, are in fact perfectly legal. The core reason for this legality lies in the contractual nature of these agreements; the terms and conditions for compensation are meticulously outlined in distribution agreements, which all parties are expected to understand and sign.

However, the question of ethics presents a more complex picture. Accounting professor Stephen Glaeser notes that while legal, the tactics are “unethical,” and perhaps even “foolish,” as they alienate crucial employees and contractors. Bridget Stomberg further adds that she can’t identify any other motivation for inflated overheads besides avoiding talent payouts, especially since these internal transactions generally don’t affect the consolidated net profits seen by a studio’s shareholders or offer tax savings.

From the perspective of those working “in Hollywood’s financial trenches,” these practices, while unusual, are explicitly *not* fraud. The compensation terms are transparently laid out; profit participants, or their legal and financial representatives, are given all the necessary information before signing contracts. They can see how the studio’s charges will effectively ensure the production company never shows a net profit. This is presented as an inherent part of the deal-making process.

To unpack the ethical dilemma, one can imagine a hot dog stand scenario where a partner, Greg, is effectively cut out of profits by the owner selling supplies to the stand at inflated prices through another company they control. While Greg might feel “screwed,” the arrangement is contractual and known. This analogy highlights that while the outcome might feel unfair, particularly to outsiders or the naive, the practices are generally considered “above-the-board” within the industry’s established legal framework, even if they often strain professional relationships.

12. **The Grand Illusion: When Hollywood Numbers Lie (or at least Obfuscate)**One of Hollywood’s most enduring myths, alongside “the camera never lies,” is the notion that “the numbers never lie.” Yet, within the intricate financial ecosystem of the entertainment industry, numbers possess their own peculiar logic. They are prone to twisting, turning, bending, and sometimes vanishing into an ether of calculated obscurity, becoming what one might call the “quarks” of the industry. Reporters and analysts often struggle to decipher their true meaning, highlighting a fundamental untrustworthiness.

This obfuscation begins with seemingly straightforward terms like “adjusted gross.” When a star is promised a percentage of this figure, the precise definition of “adjusted” can be incredibly fluid, altering millions of dollars in income. Furthermore, both independent productions and major studios engage in their own forms of numerical manipulation: indies might exaggerate costs, while studios tend to underreport them. Both are adept at bundling films for international sales, strategically offsetting a success against a loss to paint a desired financial picture.

Box office tallies, often touted as indicators of success, are merely the “tip of a numeric iceberg.” The real financial numbers that determine profitability are frequently drowned beneath waves of undisclosed expenses and opaque revenue streams. For instance, a film like ‘Suicide Squad’ might top the box office, but its actual profitability remains debatable, obscured by factors like its true production cost, star percentages, marketing outlays, and the studio’s efforts to keep it in theaters through a ‘rolling break’ strategy.

Even statistics presented with an air of authority can be deeply misleading. Consider the widely cited figures on movie piracy: a White House aide once claimed IP theft cost the U.S. $58 billion annually, a number sourced from a think tank with a clear big-business advocacy agenda. Even the Motion Picture Association of America’s (MPAA) figure of $6.1 billion for major studios had its “red flags,” failing to account for nuances like what consumers in developing nations might actually pay. These figures, while not outright “lies,” are “statistics of the most dubious kind,” deliberately chosen and framed to influence perception and policy rather than provide definitive assessment.

In the final analysis, the world of Hollywood accounting is less about outright fraud and more about a sophisticated, legally defensible system designed to maximize studio revenue and minimize profit-sharing obligations. It’s a complex dance where the numbers we casually discuss – box office totals, reported budgets – are rarely indicative of a film’s true financial success, and certainly not a reliable measure of what the talented individuals who create these cinematic experiences actually take home. For anyone stepping into this intricate industry, understanding these financial realities is not just a strategic advantage; it’s a fundamental necessity to avoid becoming another footnote in the long history of ‘unprofitable’ blockbusters.”